1. Where Do We Start?

(IN WHICH WE LEARN THAT IT’S NOT ALWAYS ABOUT WHAT PEOPLE KNOW, AND THAT YOU SHOULDN’T USE A SUSPENSION BRIDGE TO FIX A POTHOLE)

The Learner’s Journey

Are the following statements true or false?

• If you teach people about how smoking is bad for them, they’ll stop smoking.

• If someone reads a management book, that person will be a good manager.

• If someone takes a really good web design class, that person will be a good web designer.

• If you teach people the right way to do something, they won’t do it the wrong way.

Did you think any of those statements were completely true?

No, of course you didn’t, because there are a lot of complicating factors that influence whether a person succeeds or not.

Learning experiences are like journeys. The journey starts where the learner is now, and ends when the learner is successful (however that is defined). The end of the journey isn’t just knowing more, it’s doing more.

So if the journey isn’t just about knowing more, then what else is involved? What else needs to be different in order for someone to succeed?

Where’s the Gap?

There’s a gap between a learner’s current situation and where they need to be in order to be successful. Part of that is probably a gap in knowledge, but as we began to discuss above, there are other types of gaps as well.

If you can identify those gaps, you can design better learning experiences.

For example, consider the following situations. What could be the gaps for each of these scenarios?

• Alison is a project manager for a web design company, and she’s just agreed to teach an undergraduate project-management class at a design school. Her students will mostly be students in the second year of the creative design program. Most of the students are 18 or 19 years old and are taking the class because it’s a requirement for their degree.

• Marcus is teaching a two-day workshop on database design for a new database technology. This is the second time he’s taught the workshop, and he’s revising it because it was too basic the first time around.

• Kim is designing a series of elearning courses for a large global company that recently merged with a smaller company. The two companies are buying a new purchasing system to replace the older systems. The employees of the smaller company will also need to learn the procedures from the larger company.

For each of these, think about how the learner should be different—what could and should they do differently—before and after the learning experience?

In the case of Alison’s class, it could be that the gap is just a matter of knowledge: A student comes in not knowing anything about project management, and comes out knowing a lot more about project management.

But is a lot of project management knowledge all that’s needed to make somebody a capable project manager? There’s more to good project management than just knowing information. And of course that will hold true for much more than Alison’s class. Let’s take a closer look at knowledge, or information, gaps, and then talk about what other types of gaps can exist for learners.

Knowledge Gaps

Information is the equipment your learners need to have in order to perform. Having information doesn’t accomplish anything by itself. Something is accomplished when the learner uses that information to do things.

Basically, you want your learners to have the right supplies for their journey:

You also want your learners to know what to do with that information. Having the information without knowing how and when to use it is like having a really great tent that you don’t know how to put up or spending a lot of money on a really terrific camera but still taking cruddy pictures because you don’t have the abilities needed to use it.

If the only thing your learner is missing is the information, then your job is actually pretty easy, especially living in this information age. There are lots of easy, cheap ways to convey information.

Another benefit of the information age is that you don’t necessarily need your learners to carry all the information the whole way on their journey. If they can pick up less critical information as they go along, you can focus initially on the more critical knowledge that they really need to have with them the whole way.

As for all the rest of that information, think about how you can cache it for your learners so that they can easily pick it up when they need it. If they get the information when they really need it, they’ll also appreciate it more.

We’ll take a closer look at different ways to supply information to your learners in later chapters.

Is it Really a Knowledge Gap?

There’s a common tendency to assume that the gap is information—if the learner just had the information, then they could perform.

I recently worked with a client on a project to teach salespeople how to create a product proposal for potential clients. The salespeople need to be able to:

• Choose which product best meets a client’s needs

• Select a series of options so that the product is optimally customized for that client

We were working on revising an old course in which there were four slides that simply listed each of the product features.

And that was it. Hmm.

If you were learning this, do you think this equation adds up?

No, of course not—even if the learners memorized the exact information on each of those slides, that wouldn’t mean they would be able to use it well. But certainly it is always critical to start by providing the right information to the learner.

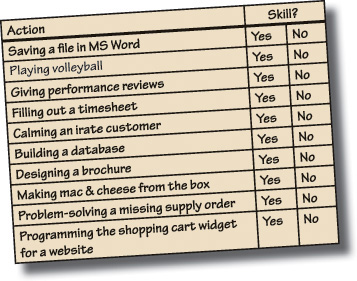

Skill Gaps

Let’s say I’ve figured out the starting point and ending point of my journey, I’ve got it all mapped out, and I have all the gear I need: Am I now ready to hit the 2000-mile Appalachian Trail?

Probably not.

Anything more ambitious than a gentle afternoon hike is probably beyond me at the moment. So what would I need to be ready to tackle the Appalachian Trail? Would more gear help? More route planning?

Not really. The only thing that is going to get me ready for a major, multi-day hike is a lot of hiking, and even a less ambitious goal would require practice and conditioning.

Time spent on practice devices like elliptical machines or stairclimbers would probably help toward the goal of a major hike; tackling an expert-level hike would require a lot of practice on less challenging hikes. Even if I sat down and memorized an Appalachian Trail guidebook, it still wouldn’t be a good idea to try it without the necessary conditioning and skills.

Learners in all disciplines are frequently in this situation. They get handed the knowledge in a book or a class but don’t get the opportunity to practice and develop skills.

There are a number of reasons for motivation gaps:

Sometimes the person doesn’t really buy into the outcome or destination.

Sometimes the destination really doesn’t make sense.

Sometimes it is due to anxiety, or concern about change.

Sometimes people get distracted or unfocused.

Sometimes people just aren’t interested in making the effort.

Sometimes people fail because they lack enough of the big picture to guide their own success.

I was recently talking with a colleague about learner motivation, and she argued that it wasn’t the learning designer’s problem. She felt that people brought their own motivation to the table and that it really wasn’t in the designer’s control. My colleague is correct that you can’t force a learner to be motivated, but as designers there are ways we can help support motivation in a learning experience. Design decisions influence people’s behavior.

For example, in a recent study (Song 2009), people were given lists of tasks. The only difference between the two lists was the font used, one of which was easier to read. Participants were asked to rate how easy or difficult they thought the task would be to perform.

Tasks presented in the easier-to-read font were rated by the participants as being easier to perform. The group given the same list in a hard-to-read font rated those tasks as being harder to perform.

This is just one example of a fairly subtle way of influencing a learner’s motivation, and paradoxically, some research suggests that things read in a harder-to-read font may be easier to remember.

There are countless decisions you might make while designing a learning experience that will influence your learner’s motivation. For example, in your content, do you dwell on all the things that can go wrong? That might be a good way to prepare the learner for troubleshooting, but might also convince them that it’s not worth the effort in the first place.

Unlearning: The Special Motivation Gap

One of the things you may need to consider in your learner’s journey is whether the new learning is going to require doing something familiar in a new manner. If people are required to change the way they do things, then they are going to stumble over old habits. If they automatically do certain things, they are going to have to make a conscious effort to not do those things—a process called unlearning. This is more difficult than just making a conscious effort to do something new, and, not unimportantly, it can make people grumpy.

When Tiger Woods changed his golf swing, his game would take a hit for a while until it (usually) improved again. This is a fairly difficult process for an athlete, because it not only involves adding the new technique but also requires unlearning the old technique.

As we gain proficiency in something, the memories around that proficiency become streamlined in our brains. We get progressively more efficient in how we access and use the information and perform the procedures around that task. This is an important part of learning—if it didn’t happen, then riding a bike for the thousandth time would be just as difficult and exhausting as riding a bike for the first time.

This streamlining process is a natural blessing for learning, but it poses a difficulty for re-learning. When learners must change or replace an existing practice, you have to deal with the fact that your learners already have momentum. They are already going in a particular direction, at a pretty good clip. And they have many parts of the process automated.

Automatic Processes

When you automate something, you relegate control of that task to a part of the brain that doesn’t require much conscious attention.

When a task is new it requires a lot of brain resources. When you are first learning to ride a bike, for example, you need to put a good amount of your conscious attention on the task of staying upright.

When you become proficient, you don’t have to consciously think things like “I’m tipping! Omigosh, whaddoIdo? WhaddoIdo?” Instead, your body just adjusts left or right without your having to think about it, and you can concentrate on other important thoughts like “Oh #$%^@! That log wasn’t there the last time I came down this route!”

This has significant implications for learning.

Let’s go back to our example with Kim from the beginning of the chapter.

Old information and procedures get in the way of new information and procedures. Have you ever noticed that when someone is not a native speaker of your language, the word order in their sentences can be a little weird? This is called L1 interference: Your knowledge of your first language interferes with your ability to speak a second language.

If you are asking your learners to change an existing practice, you are probably going to have some motivation issues to contend with. In those instances, there are a couple of things to be aware of.

First, change is a process, not an event. You absolutely cannot expect someone to change based on a single explanation of the new practice. They need time and repetition to ease back on the old habit and start cultivating the new one.

Second, backsliding and grumpiness are part of that process—they don’t mean that the change has failed (although that can happen too), but they are frequently an unavoidable part of even successful changes.

Habit Gaps

Sometimes, people have the knowledge, skills, and motivation and there still may be a gap. For example, a new manager can have seen the importance of giving good feedback, have learned a method for giving feedback, and truly believe that it’s an important thing to do, and—even after all that—still struggle to give feedback when needed. Because it’s not a habit.

For most of us, a large percentage of our day is habit-driven. When I get up in the morning, probably the first half hour of my day is on auto-pilot (let the dog out, make coffee, brush teeth, etc.).

The difficulty with habits as a gap is that most of the traditional learning solutions have only mixed results at best. Have you ever said any of these?

If you ever have, you know that they fall firmly into the “easier said than done” category—as do most habits, whether they’re new habits to be learned or old habits to be unlearned. As a result, habits need a different learning approach, which we will discuss in a later chapter.

Environment Gaps

Let’s say your learner has good directions, is fully prepared, is in good shape, and is raring to go. Nothing should stop them now, right?

Sometimes the path itself isn’t set up to let people succeed:

Environment gaps, or challenges, can take different forms in an organization. For example, if you want somebody to change a behavior, does the process support it?

Are there materials, references, and job aids to support the learner when they get back to their work environment?

Do they have everything they need in terms of materials, resources, and technology?

Are people being incentivized and rewarded for making the change?

Is the change being reinforced over time?

Communication Gaps

Sometimes a failure to perform is due not to a lack of knowledge but to bad directions or instructions.

This isn’t really a learning issue—this is a case of miscommunication. It can happen for all sorts of reasons. Sometimes, the person communicating the direction doesn’t really know where they want people to go; they don’t know the goal.

Or sometimes, the person communicating knows where they want people to go but can’t adequately communicate that knowledge.

Occasionally, the person giving the directions says one thing, but either doesn’t support it or really intends something else.

For example, let’s say that one of Alison’s students is using all his shiny new project-management abilities on building a website for his uncle, but a few weeks into the project, it’s not going very well.

The website is behind schedule, the person doing the graphics can’t finish them, and the design for the whole gallery section is a mess.

Does that mean that Alison’s student didn’t really learn everything he needed to know about project management? Maybe he’s making rookie mistakes, despite everything he learned in class?

Or could it be that the uncle is the client from hell who didn’t say that he was leaving the country for a month, changes his mind frequently, and forgot to mention that he wanted a gallery section on the website in any of the initial meetings? That might be why.

So how much of this is a learning issue? None of it, really, but communication issues can sometimes masquerade as learning issues.

Frequently, the best you can do in those situations is document the issue, handle the politics, and do no harm to the learners, if possible.

Identifying and Bridging Gaps

So when you are mapping out the route, you need to ask yourself what the journey looks like.

Knowledge

• What information does the learner need to be successful?

• When along the route will they need it?

• What formats would best support that?

Skills

• What will the learners need to practice to develop the needed proficiencies?

• Where are their opportunities to practice?

Motivation

• What is the learner’s attitude toward the change?

• Are they going to be resistant to changing course?

Habits

• Are any of the required behaviors habits?

• Are there existing habits that will need to be unlearned?

Environment

• What in the environment is preventing the learner from being successful?

• What is needed to support them in being successful?

Communication

• Are the goals being clearly communicated?

Examples

Let’s identify the gaps in a few scenarios.

Why This Is Important

Several years ago, I was working on a proposal for a prospective client. The client had come to the company I worked for and said, “We have a problem with a high employee turnover rate. We want a training course on the history of the company to reduce that rate.”

We gently suggested that if they had a high turnover rate, it was probably not primarily due to employee ignorance of company history, and would they like us to look into other possible causes?

Yeah, we didn’t get that contract. Oh darn.

In Chapter 3, we’ll take a look at how to set good goals for learning, but before you get to goals, it’s really important to define the gap you are trying to fill or the problem you are trying to solve.

If you don’t start with the gaps, you can’t know that your solution will bridge them. You can build a suspension bridge to cross a crack in the road, or try to use a 20-foot rope bridge to span the Grand Canyon.

One of my all-time favorite clients was a group that did drug and alcohol prevention curriculums for middle-school kids. When they were initially explaining the curriculum to me, they talked about how a lot of earlier drug-prevention curriculums focused on information (“THIS is a crack pipe. Crack is BAD.”).

Now does anyone think the main reason kids get involved with drugs is a lack of knowledge about drug paraphernalia, or because no one had ever bothered to mention that drugs are a bad idea?

Instead, this group focused on practicing the heck out of handling awkward social situations involving drugs and alcohol. Kids did role-plays and skits, and brainstormed what to say in difficult situations. By ensuring that the curriculum addressed the real gaps (e.g., skills in handling challenging social situations), they were able to be much more effective.

If you have a really clear sense of where the gaps are, what they are like, and how big they are, you will design much better learning solutions.

Summary

Summary

• A successful learning experience doesn’t just involve a learner knowing more—it’s about them being able to do more with that knowledge.

• Sometimes a learner’s main gap is knowledge, but more frequently knowledge and information are just the supplies the learner needs to develop skills.

• Use the question “Is it reasonable to think that someone can be proficient without practice?” to identify skills gaps. If the answer is no, ensure that learners have opportunities to practice and develop those skills.

• You need to consider the motivations and attitudes of your learners. If they know how to do something, are there other reasons why they aren’t succeeding?

• Change can be hard because learners may have deeply ingrained patterns or habits they have to unlearn, and you need to expect that as part of the change process.

• The environment needs to support the learner. People are much less likely to be successful if they encounter roadblocks when they try to apply what they’ve learned.

• Sometimes it’s not a learning problem, but rather a problem of communication, direction, or leadership. Recognizing those instances can save a lot of effort in wrong directions.

• If you have a well-defined problem, you can design much better learning solutions. It’s always worth clearly defining the problem before trying to define the solution.

References

Ellickson, Phyllis, Daniel McCaffrey, Bonnie Ghosh-Dastidar, and Doug Longshore. 2003. “New Inroads in Preventing Adolescent Drug Use: Results from a Large-Scale Trial of Project ALERT in Middle Schools.” American Journal of Public Health. 93(11): 1830–6.

Song, Hyunjin and Norbert Schwarz. 2009. “If It’s Difficult to Pronounce, It Must Be Risky.” Psychological Science 20 (2): DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02267.