Chapter 03

Stage 3 Developed Design

Stage 3

Developed Design

Chapter 03

Overview

This chapter lays out the characteristics of the Stage 3 Developed Design process. This stage seeks to interrogate and develop the Concept Design through more detailed knowledge of the building materials and systems to be employed, and to understand how their cost and construction criteria might affect the programme. At the completion of the stage, the design team will present a range of updated and new detailed Project Information to enable the client to sign off the stage confident that the project parameters are deliverable and will be met.

Approaching Developed Design

After the creativity and freedom often characteristic of the design process during Stage 2, the Developed Design stage can feel like a series of proofs for the propositions made during Concept Design. The design processes employed during the Developed Design stage require disciplined and coordinated scrutiny across the design team in order to ensure success against the parameters set for the project. This stage also involves considerable iteration in pursuit of a design that carries the concept forward but that also prepares the components of the project for the rigours of Stage 4 Technical Design in a way that avoids needing to amend the Stage 3 design to accommodate new factors.

It is within RIBA Plan of Work Stage 3 that the efforts of the design team really become fixed into place, and the various Project Strategies set up in earlier Plan of Work stages converge to make the coordinated design more rigorous and easier to achieve. We have seen in Chapter 2 that a planning application may have been programmed in at Stage 2 for a project- or client-specific reason. For many projects, however, the planning task sits more naturally within Stage 3. At this stage, the project will have reached a point in its development at which many more significant decisions will have been made and coordinated with the outputs of the whole design team. The client will also be able to really see the qualities and detail of the building that they have commissioned, and will have confidence in the design and cost information that is supporting the design. Planning applications made at the end of Stage 3 are significantly more robust than earlier-stage submissions, the designers having had the opportunity to produce the kind of detail that planners and the public are looking for from their built environment.

The planning process places the project into the public domain, and all the documentation that accompanies a planning application becomes publicly accessible material. Despite a pre-planning application process, which seeks to minimise areas of concern or difference between the project team and the planning authority’s team and policy documentation, this is an uncertain time in the project’s life. The planning system and its decisions are controlled initially by local, democratic processes, and, although a variety of preparations can be made prior to a determination of the application, the progress of the project beyond this point rests with the political leaders of the locality.

What is Stage 3 Developed Design?

The Developed Design forms Stage 3 of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 and represents the culmination of the resolved and coordinated design. It is the fourth stage of the Plan of Work framework and, in this Stage Guide series, sits with Stage 2 Concept Design as one of the two stages at which significant iteration occurs in the creation of a building project following the Initial Project Brief but before the technical detail of Stage 4. The completion of Stage 3 is often regarded as the threshold between creating and delivering a project.

What is a Developed Design?

The ideas that are generated during the Concept Design stage show creative responses to the project brief: sometimes loose and exploratory, experimental without exact scale or the restriction of exact dimensions, but resulting in a cogent response to the client brief. The Developed Design stage focuses on rationalising and validating the detail of the decisions already made in order to allow the design team to be able to prove that the design works as a whole and checking further its affordability. This involves dimensional accuracy, checking elements of design against the appropriate regulations and ensuring that the actual construction requirements are not going to affect any assumptions made during previous stages. The client clearly has an interest in understanding the balances established by the design team in reaching this stage, and the coordinated effort necessary to ensure that the design team disciplines can each sign off against their own areas of expertise. It remains very important at Stage 3 that the design team continue to look ahead, so that they can clearly understand how the stages completed up to this one can contribute to the success of the whole project. The client should be aware of progress through this stage, but does not need to be directly involved unless some revision of the Concept Design conclusions becomes necessary.

Coordinating Design

Coordinating Design

It is no accident that when teaching building-design disciplines of all types, tutors will reinforce the need to account for the role and output of all the other design team members within this Developed Design stage of the process. Of particular importance to successful Project Outcomes is the coordination of structural and services information with each other, and with the prime internal building elements and external envelope. It is critical that each design team member is afforded sufficient time and opportunity to contribute to the delivery and management of what becomes the core stage of design coordination.

At Stage 3, the coordinated design ensures that there is dimensional fit and spatial compatibility between elements of the project designed by different design team members. Depending on the Technology Strategy for the project, this may be handled as a manual check or the clash detection module of a building information model.

Below are some areas of design coordination that will be established, and which should be anticipated during Stage 3.

- Confirm the structural-grid dimensions in plan at each level of the building. Do they offset at all, creating differing relationships with building elements on different levels?

- Establish the overall depth of the structural zone, and how often in each plan direction this depth is reached. What are the resultant restrictions on floor-to-ceiling heights?

- Consider what the relationship between structure and envelope is going to be, and what effect this might have on internal or external appearance and finishes. Does the structure ‘read’ on the outside, or will there be awkward corners and encasements in areas where hard finishes, such as tiling, is proposed?

- Confirmation of the main building services’ vertical and horizontal distribution routes. Are they sensibly located for economic installation? Do they follow acceptable routes through the building? Are there any acoustic issues connected with service distribution that would affect areas of the building in use?

- Establish the depth of the building-services zone, and the parameters for changes in direction of services. Bends in services, and services changing direction to avoid structure, need the correct spatial fit; reducing the number of times that this happens can help reduce costs too.

- Establish whether the structure can accommodate building services running through it, and at what centres. Is there an opportunity to create a single zone, within which a coordinated structure and services solution might work?

Consider where building services will need to penetrate the internal walls and external envelope. The size and location of services terminating on external walls and roofs need coordinating with elevation materials and arrangement, in order to avoid undesirable effects on the building’s appearance.

What is the delivery of Concept Design in detail?

Concept Design creates an intention. For example, in our project Scenario E, in order to create an ‘industrial aesthetic’, the architect wants the structural steelwork junctions and air-handling ductwork to be on show below the floor soffit. They know that to pull this off a high level of coordination is necessary, and that both structural and services engineers need to ‘buy into’ the concept as it involves them also thinking about what their elements of design will look like. In another example for the university building in our Scenario C, large sections of wall space need to be left free of services equipment or structure in order to act as display and projection space. The services design will need to respond to this requirement by avoiding switches, thermometers, alarm sensors, etc. on these walls, even though a standard design solution would inevitably seek to place some of these items on them.

The design element in question might be quite substantial – like a ‘concept I’ that has been conceived as part of a relevant street scene, responding to an Initial Project Brief that required a ‘civic’ presence. The choice of materials, the detailing for weathering, the marking of openings and expansion joints all contribute to the eventual impression of the façade. Developed Design proves that the delivery of these ideas in reality will contribute to the whole design, as had been envisaged during Stage 2.

During the Developed Design stage, other design team members become more actively engaged in responding to the spatial and environmental parameters of the building, and this is where the rigorously written and reviewed Project Strategies come into their own. A well-constructed strategy sets out the requirements of the brief, the condition under which those requirements might or must be met and any existing or presumed constraints that need to be taken into account. The Concept Design will have illustrated how these Project Strategies are most likely to be met in conjunction with each other, and when they subsequently come under review during the Developed Design stage it will be clear how the design team must work to deliver these coordinated elements of the building project. Clear Project Strategies will be able to relate these design intentions, whether it is the same designer working on the project or new members of the design team.

Clash Avoidance Using Bim

Clash Avoidance Using Bim

A key component of the coordinating design task is avoiding clashes between building elements which if remaining undetected can cost time and money on site modifying or changing aspects of the design. Typical clashes of building components that require detection at this stage might include

- Underground services and foundation arrangements

- Structural beams and horizontal services

- Structural bracing and external wall elements, including doors, windows and insulation

- Vertical service risers and structural and architectural components

- Bulkheads over stairs and other areas where head height is critical

- Roofing components, particularly awkward geometry or curved elements with structure and building services.

Building Information Modelling (BIM) and the emergence of 3D software tools has made clash detection much simpler and at Stage 3 allows modifications to take place without consequences on the building contract. The construction industry is aiming to achieve Level 2 BIM (Managed 3D model environment for separately produced discipline models) for publically procured works by 2016. Level 3 BIM envisages a single model worked on by the design team where clash avoidance happens during the normal course of the design developing.

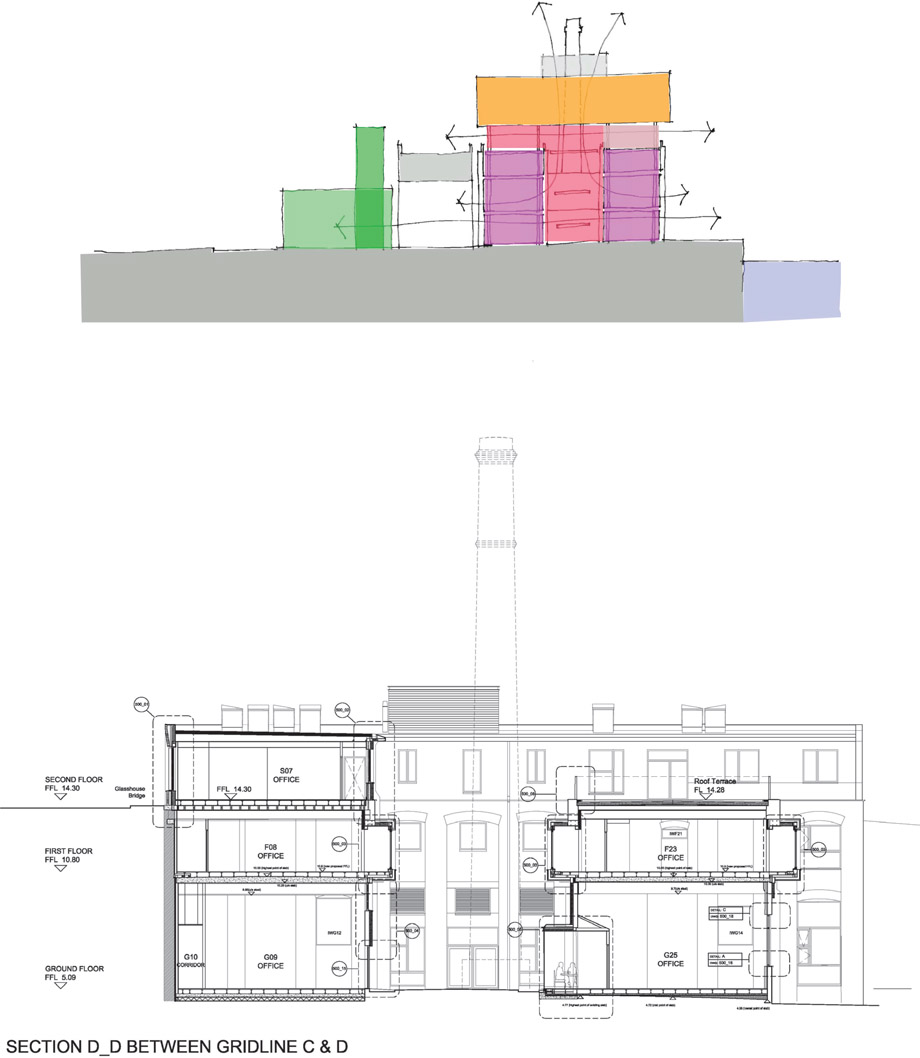

3.1 A sketch comparison of a Concept Design and Developed Design from the same project.

Describing the Project

Describing the Project

All project team members will be familiar with describing the building project to a range of stakeholders. The language, expressions and detail used to do this change, of course, depending on who the audience is. These descriptors are important as part of the Information Exchanges that happen all through the project. Obviously, verbal exchanges are not often recorded, and design dialogue of this nature represents a high proportion of the development time spent between design team members exploring and modifying the building design.

So a Stage 2-type statement like ‘the building envelope will be made of brick’ is enough to evoke a sense of that design decision, but during the Developed Design stage the architect might add that ‘the simple “punched” hole in the brickwork is lined with an aluminium flashing to four sides with the window frame set back from the face by 250 mm’. This better understanding of how the brick will form each window opening and how it is finished will add detail, complexity, time or cost to the project as a whole.

Also, it should be possible to be clear about the dimension, performance in use, availability and cost of the brick without writing a full specification for it. If as many elements of the building’s construction as possible are identified with this level of information, the Developed Design will evoke a substance and quality in all respects that will survive the investigative rigours of future stages.

What Effect will Procurement: decisions have on Stage 3?

As discussed in Chapter 2, the procurement of design and construction services for building projects will vary depending on the choice of Building Contract and the client’s priorities for the three principal components of any project – quality, time and cost.

The impact of procurement is tracked in the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 under Task Bar 2. This is a variable task bar that can have very different levels of activity in each stage, depending on the decisions made at the initial briefing stage. The amount of work required from the design team across all Plan of Work stages changes very little between procurement routes – the difference generally lying in who the Information Exchanges are prepared for, and the level of engagement of the design team with the client or end user in preparing the design through Stages 2 and 3.

Procurement Choices for Cost

In simple terms, the later a project is tendered the more reliable the price will be, as it will be based on Developed Design and possibly Technical Design detail. Maintaining project team control over the design usually gives the highest design-quality results. This process tends to take longer to achieve, so some forms of contract seek to fix a price much earlier in the Project Programme. However, the earlier the works are tendered the less reliable the price is, as it is based on undeveloped design information and will contain client contingencies and provisional sums or the contractor’s assessment of the risk remaining in the project.

In all situations, the client’s willingness to retain risk or requirement to transfer it to the contractor will dictate both the procurement choices and the extent of eventual control over cost decisions. Cost certainty does not mean cheap, and the loss of control over design is often very hard for clients to accept.

3.2 An extract from a procurement choice flow diagram relating task bar activity to Plan of Work stages under different procurement priorities.

The choices made for procurement of the building project will be fundamental to the nature of relationships in the project team. These choices do not affect the sequence of work described in the RIBA Plan of Work, or the type or level of completeness of the technical design information required. They can affect the information to be included in information exchanges, but do not diminish the need to put in place Project Strategies, information protocols and cost information at each stage.

The Impact of Procurement Routes on Stage 3

- Traditional – the Developed Design will assist in pre-tender cost estimates, and allows the client to remain in control of the design process. This level of control can change due to external factors, but generally means that the design team are able to focus on design quality and clarity of information. The Stage 3 Information Exchange clearly sets out how Stage 4 is going to deliver tender information in order to provide a credible construction cost.

- Design and build, single stage – most single-stage procurement is tendered at the end of Stage 3, when the design is fixed but the expertise of the contractor and specialist subcontractors can bring benefits to the construction and cost process. Information at this stage has to describe the full design intent even when it is not all declared in drawings and specifications.

- Design and build, two stage – the two-stage tender process is most useful when the contractor and specialist subcontractors are able to contribute their expertise in parallel with the design team during Stage 3. An agreed construction cost at the end of Stage 3, with this level of contractor input, before a building contract is signed contributes significantly to maintaining design quality in the finished building.

- Management contract – Stage 3 information will be developed concurrent with Stage 4 packages, in line with the expectations of the. For this type of procurement programme, the lead designer maintains the coordination of all elements of the project.

For more information on this subject, please refer to Construction: A Practical Guide to the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 Stages 4, 5 and 6 by Phil Holden – the third book in this series.

Procurement Choices for Specification

Procurement Choices for Specification

Specification is the written part of the Stage 3 information output, which describes what materials, building products and systems the building will be made of. It can be produced with very different levels of detail depending on the procurement choice:

- Traditional – the design will be accompanied by an outline specification at Stage 3. This identifies in generic terms the materials and product types chosen for the project. This will be developed fully during Stage 4.

- Design and build, single stage – specification for single-stage procurement is included in the Employer’s Requirements tender document. This will have been developed to include all elements of the project that are specific client requirements (eg a metal standing-seam roof from one of two manufacturers), leaving other areas as quite generic performance criteria (eg a high-pressure laminate WC cubicle system with easily available replacement parts), giving the contractor flexibility for particular products in their Contractor’s Proposals document at tender return.

- Design and build, two stage – at the first stage of the two-stage tender process, the specification is likely to be quite generic, as it is in the traditional route. Working with the contractor through the second-stage process allows the specification to develop alongside the design and cost plan. At second-stage tender submission, these elements should be coordinated into a comprehensive Contractor’s Proposals document.

- Management contract – the Stage 3 specification will be negated by the need to issue Stage 4 in packages. The lead designer and contract manager have to maintain an overview of each specification package, to ensure that interfaces are carefully considered.

How to deal with Stage 3 being the completion of the commission

There are certain circumstances in which Stage 3 Developed Design will be the completion of the design team’s appointment. This may have been made clear from the beginning, because the appointment was to submit a design to gain planning permission for a site. It may be the result of a procurement route required for the project by the client or a funding agency, which means that design team services are competitively tendered ahead of Stage 4. It may alternatively result from the Building Contract, necessitating a contractor taking responsibility for the design from the beginning of Stage 4 and not requiring the continued services of the design team that had been responsible for the design up to that stage.

It is important to recognise that these circumstances occur considerably more frequently now than in the past. It is also important to recognise that if this situation might be the case for the project being worked on, then there is an additional responsibility on the lead designer and the design team to complete the Stage 3 Developed Design Information Exchange in a manner that can be easily understood and continued by the subsequent design team.

How Does the Design Programme: in Stage 3 differ from that in Stage 2?

At Stage 2, the Design Programme organises elements of the emerging design in relationship to one another, resulting in a strategic Concept Design. During Stage 3, the Design Programme relates directly to coordination of the activity of the design team. Encouraging design declaration and dialogue to avoid conflicts in building elements results in a fully coordinated Developed Design at the Stage 3 Information Exchange.

The Design Programme will be the responsibility of the lead designer, and during Stage 3 it sets out appropriate time periods for key aspects of the Developed Design, design team and client meetings and design workshop events (discussed in Chapter 2). It can be used very effectively by the lead designer to encourage successful design team collaboration during Stage 3. It will culminate in an agreed and coordinated design that goes forward for approval to the client. The Design Programme will most likely at this stage include planning application and Building Control procedures, and may also include third party consultation or other stakeholder events that may impact on the design process.

The reason for the change of emphasis on collaboration in the Design Programme during Stage 3 is twofold:

- Information at Stage 3 is used to demonstrate that the Concept Design can be realised. Real components and construction products are brought together by different design team members to form a building that captures the essence of the Concept Design and can be costed. It is important to avoid change after planning permission has been granted and as the project enters into Stage 4.

- At Stage 3, time is the element of the project most likely to have defined parameters. At the outset of the project it is relatively easy for a client to say, irrespective of the project’s scale, ‘I’d like an x building project, built for £y by z date.’ Unlike cost, which can fluctuate during the development stages, time is a linear factor in the project and a day lost is lost for good. This fact makes the management of the Design Programme during Stage 3 a critical contribution to the success of the Project Programme.

3.3 An extract from a Design Programme.

As the project enters Stage 3, the key project milestones that represent significant financial commitment from the client are coming into sharp focus. Typically, a planning submission fixes the design scope, and a start of construction on site is programmed in with a handover date for the completed project in view. By comparison with Stage 2, the Stage 3 Design Programme feels targeted and very time driven. Meeting deadlines to maintain programme, working collaboratively with other design team members and producing a coordinated design will result in a qualitative Information Exchange on time with good Cost Information and significantly less prospect of future design change.

What Do you Need for a Planning Submission?: (Validation checklists, information schedules, resource planning)

For the majority of projects, Stage 3 will include a planning application submission. This decision will have been taken during the Stage 1 briefing activity and be recorded on the Plan of Work Variable Task Bar 4, (Town) Planning. Depending on the nature and scale of the project, a significant period of formal pre-application engagement might be dedicated to meeting with and understanding the planning authority’s opinion, planning policy and submission requirements. These activities will be recorded on the Design Programme, as their outcomes affect the iterative design process and, consequently, potentially affect the programme. Each planning application will be made up of validation requirements from a national and local list. It is good practice to formulate a validation checklist at the outset of Stage 3 in order to inform the scope of work, responsibilities and timescales for each piece of work, as they will inform other parts of the scope. Validation requirements are often set out in a checklist format, and usually available as a downloadable document from the local council’s website.

These validation checklists are very likely to include a variety of specialist reports, which might form part of the planning-submission package depending on the scale and complexity of the project. If these required items are missing, the submission will not be registered as a ‘live’ application and, potentially, delay might be caused to the programme. It is quite usual for urban planning applications to be accompanied by the following reports:

- Desktop Site Investigation – the site conditions are recorded using historical maps to assess previous development; archive information on utilities, mineworkings or other licensed underground activity are logged in order to be able to consider site conditions for foundations and other civil-engineering structures.

- Geotechnical surveys, including contamination assessments – intrusive ground surveys using boreholes, trial pits and window sampling to confirm load-bearing capacities and contaminants.

- Ecology surveys and tree surveys – recording biodiversity and ecological value, and identifying species of flora and fauna.

- Heritage Impact Statement or Conservation Area Statement – considering impact of proposals on listed buildings or structures in Conservation Areas.

- Planning Statement – planning policy referred to as justification for the scheme being acceptable.

- Transport Assessment (for large projects), Transport Statement, Green Travel Plan outline.

- Noise or Vibration Survey – recording of noise or vibration factors that may affect proposed use.

- Statement of Community Involvement – it has become common practice to organise a consultation or engagement event with the general public before a planning submission. Comments and actions leading from those consultations are recorded in this statement.

- Design and Access Statement – an explanation of site context, design concept and design development, and proposals for accessibility across the project. Information produced during Stages 2 and 3 and have informed the design should be included in this statement.

Rural or suburban applications might require some of the above and the following reports:

- Sequential Test or Town Centre Assessment – to resist unnecessary out-of-town development and ensure sustainable settlements.

- Visual Impact Assessment – consideration of impact of development on established or relevant views.

It is worth noting that this list in effect becomes the majority of the contents of the Information Exchange at the completion of Plan of Work Stage 3 – and it may be worth considering the Design and Access Statement as the ‘organising document’ for the design information and these various reports, acting as one document doing two jobs.

The point to make here is that each of these reporting requirements will take time, and they must be planned appropriately within the Design Programme. Project Strategies are ideal for identifying what documents should be commissioned and when. Some of them will respond to project proposals, as they are reporting on the scale of impact of the proposed scheme (for example, the ecologist’s assessment of wildlife habitat impacts). But some need to be carried out earlier, as they will impact on the design proposals (for example, the Site Investigation might identify an area of the site not able to be economically developed due to poor load-bearing capacity).

These reports should form part of the formal pre-application process, so that any impacts identified can be mitigated in the scheme design before proceeding to a planning-application submission. Careful and early consideration of these validation requirements will inform the Stage 3 Design Programme and help to ensure adherence to the target submission date for planning.

Reviewing Stage 2 Project Strategies

There is mention earlier in this chapter of the need to review some Project Strategies during Stage 3. All Project Strategies should be reviewed during this stage, even if some require only minor or no adjustment in order to remain relevant. The aim of the design team should be to complete the stage with a fully aligned set of Project Strategies, with changes from the previous stage highlighted.

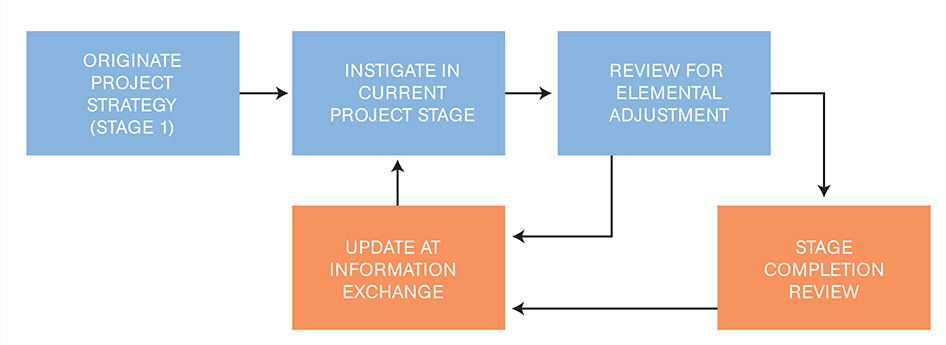

3.4

A generic Project Strategy review cycle.

During Stage 3, the level of detail that needs to be declared and understood is likely to warrant very significant updating of several Project Strategies that, in some instances, are linked. For instance:

- The Maintenance and Operational Strategy will be able to develop from a set of client requirements laid down at Plan of Work Stage 1 into a detailed set of provisions that the building design must allow for at this stage in order to avoid unwanted design change in later stages. For instance, the developed building design will make provision in its accommodation schedule for plant areas that during Stage 3 will be sized accurately, with layouts produced indicating the main incoming and outgoing services. Optimum locations for service risers, cleaner’s equipment and general storage around the building will have been chosen, and each of these will inform the provisions of the Maintenance and Operational Strategy.

- The Health and Safety Strategy will be very significantly informed by the development of the plant room and roof-access protocols, and plant-replacement strategies, which all form part of the review of the Maintenance and Operational Strategy at this stage.

- These decisions together with design development in aspects of off-site assembly and manufacture will in turn impact on the Construction Strategy and the review of project Risk Assessments.

The review process illustrated in Figure 3.4 will be happening throughout the Stage 3 period, informed by the continued and qualitative development of the building project. The design team will need to be alert to the issues that impact on their sphere of operation, and perhaps influence the design decisions they make during this stage. The Project Execution Plan will include a review regime for Project Strategies, setting out when the reviews should happen, who should attend review meetings or workshops, and the expected levels of output from these. For example, the Communications Strategy for the project will have established how digital communications and digital collaboration platforms will be utilised, and Stage 3 is a good time to review how that is working. The Project Execution Plan will be subject to review itself, and this process will help to record where changes are made across all Project Strategies and act as a directory of all activity during Stage 3.

How Project Strategies assist with statutory compliance

It should be considered useful to the design team to structure the relevant Project Strategies so that their contents are separated into, firstly, responses to statutory requirements and, secondly, those that respond specifically to project requirements or client initiatives. Typically, the extent of any Project Strategy that covers, for example, how any Health and Safety Regulations will be met may also touch on requirements that contribute to the safe operation and use of the completed building project. This distinction is important because it allows elements of proposed change or modification to the project proposals to be assessed against their impact on compliance on the one hand and project risk on the other. Clearly, the design team have a duty to avoid altogether any client exposure to non-compliance with regulations or legislation, and conscientious management and continued development of Risk Assessments during the design stages will guarantee this. Communicating the outcomes of Risk Assessments to the whole project team and maintaining a regularly reviewed project risk register is essential to good design development, and no less significant a task during Stage 3 than during the Stage 4 Technical Design development ahead.

Opportunities for Research: in developing Project Strategies

In an ideal scenario, Project Strategies will develop in a linear pattern. Having set out at an early stage what the broad Project Objectives are in each specific strategy area, their development will follow the pattern of increasing knowledge around subject detail and emerging project criteria.

At Stage 2, the Project Strategies will have been reviewed in order to take account of new and emerging factors in the project – for example:

- The shape or massing of the building might affect the Sustainability Strategy.

- Site Information might influence the Construction Strategy or procurement strategy.

- The height of the building and the type of roof being proposed might impact on the Health and Safety Strategy.

As discussed above, these Project Strategies will be reviewed again, during Stage 3, in order to reflect the level of technical product and construction detail being investigated as the project become less generic. The key driver of this activity in Stage 3 is the need to increase the amount of fixed Project Information and to reduce to an absolute minimum the opportunity for principal project criteria to change during Stage 4 Technical Design.

During the individual and collective processes undertaken by the design team leading up to Stage 3, there invariably will have been opportunities for research projects to take place. In some cases, the development of new approaches, techniques or products that could emerge from the requirements of the project – and the desire of the project team to innovate or explore new possibilities – will have enhanced the project design outcomes at Stage 2. During Stage 3, the status of these research projects will be reviewed and possibly extended, provided that their Project Outcomes can be realised within the Stage 3 Design Programme.

This form of research and innovation in building projects is often associated with expensive schemes that can afford the prototyping and testing of significant new approaches to construction, or academic research projects that take time and have the objective of broad application in the construction industry. This scale of research often appears quite glamorous, but on occasion promotes very significant technological advances in building elements. These usually happen in conjunction with manufacturers and their product or process designers, who can see commercial benefit in the end product of the research. Much more common are circumstances within a building project that offer the opportunity for a piece of simple and inexpensive research. This might revolve around processes within a design practice rather than products that are specific to the project, but – if well set up, executed, recorded and disseminated – it will grow the knowledge base of the practice and the design team, and may have reputational advantage for the project and the design team involved.

Identifying and Undertaking Simple Project Research

-

A research project may emerge within a quite ordinary scenario – in response, for example, to a design requirement for a glass wall to perform in a certain way at dimensions that are unfamiliar to the design team, and when, while keen on the aesthetic value of the glass wall, the client has instructed that there must be no significant impact on the elemental cost plan for the building. On previous projects, the architect had only paid attention to the size of the window frames, ensuring that they fitted into whole-brick dimensions both vertically and horizontally, and so had never had reason to ask about glass manufacture. In the course of this project, however, the architect discovers, in conversation with the glazing supplier, the exact dimensions of the large glass sheets that are supplied prior to any cutting. The supplier invites the architect to visit their factory, where they are shown the process from supplied sheets to ordered product. It becomes clear that the number of cuts made to a supplied glass sheet, together with the waste generated from those cuts, affects the cost per square metre of the supplied building element. This knowledge, together with a re-examination of design criteria, throws up the possibility of achieving the desired effect of a large glazed area while avoiding cuts to the glass, so that the relative coverage cost of the material does not affect the cost plan.

The architect writes a short research paper on this discovery, including an investigation into how this approach reduces material wastage from the process and how that might count towards an environmental rating for the building project. Clearly this knowledge can easily be shared, used on future projects and indicates the skill and dedication of the design team in wanting to achieve the briefed building project.

- In another instance, the design team might seek to compare, on a much wider basis than normal, the relative merits of types of wall insulation, taking into account their whole-life and environmental costs rather than just their capital cost. In this building, the Project Programme is tight and of high priority – and one possible aspect of practice-based research could revolve around construction times for different forms of construction and the insulation they can accept, always taking into account the consequences for programming relative to cost. The outcomes for questions like these are not necessarily ground-breaking in an industry-wide context, but they can represent significant positive impacts within the project itself. An example of designing to cost

The seeming familiarity or simplicity of these project-based examples indicates that simple research of one sort or another happens more often than imagined. Following the framework of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013, and recording outcomes formally, helps to encourage research attitudes and allows the results to be shared easily. Such activity increases the knowledge base within the individual practice in the first instance, but then, more broadly, across the design or project team.

Setting Up Change Control Procedures: for this and future stages

On larger and, in particular, more complex building projects, Change Control Procedures may have been introduced before Stage 3. In all cases, it is a very useful project-control mechanism to introduce Change Control Procedures from the outset of Stage 3 particularly as the concept design and the aligned final project brief have been signed off by the client. Change control is a clear method for logging the following systematically:

- Changes to project criteria and detail.

- Who, or what circumstances, made the change necessary.

- The estimated cost of the change (design and construction costs).

- Any impacts on the Design and/or Project Programme.

- All the Project Information that needs revision in order to reflect the change.

A Change Control Procedure ensures that the client signs off the change before it is circulated to the design team to undertake the revisions necessary. It is good practice in a collaborative design team environment to have tested the proposed change with design team members, so that the impacts are widely understood and agreed.

3.5 An example of change-control data template.

This mechanism of recording changes to the design, particularly during Stage 3, allows progressive design changes and cost increases and decreases to be tracked and monitored. During project meetings, the record of change control creates a useful history of change decisions, the reasons for the changes and a log of the authorisation for change. allowing informed discussion on the subject if required. This management element of the project is most likely to be encapsulated within the Project Execution Plan at Stage 1, along with a record of who takes responsibility for keeping the change control records up to date.

Developing and executing third party consultations

No building project exists in isolation, and in every case a series of third party consultations needs to take place in order to inform the project scope, cost and programme. Stage 3 is an ideal period in which to undertake these consultations, as the design team are able to say generally what the project proposal is and to absorb the information from the consultation into the Developed Design workflow. Third party consultations are noted under Task Bar 5 Suggested Key Support Tasks.

Here are some third parties commonly consulted during Stage 3, and what to expect from them:

- Amenity and civic societies – special-interest groups that may be active in the project location. For example, The Georgian Society, The Victorian Society or The Twentieth Century Society. By its very nature, the commentary received from amenity or civic societies will have a narrow focus and rarely seek to see scheme proposals in the round.

- Utilities providers – water, gas, electricity and telecoms services will all be delivered to the new project by different organisations. Each utility, in turn, may need to consult separate infrastructure, distribution and connections companies. Long lead-in times for new services often impact on the construction programme, and early knowledge of this can help establish the programme’s critical path.

- General public – for around 30 years now, it has been considered good practice by many clients – particularly public-sector and quasi-public-sector bodies, like Housing Associations – to hold a form of consultation on proposed developments before they are submitted for planning permission. Listening to local people will inform design proposals, and may mitigate formal objections during the planning application period itself.

- Design Review – CABE (the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment) introduced a UK-wide network of Design Review Panels that provide an independent voice for design quality prior to planning. Design review commentary is usually extremely helpful at Stage 3 in identifying both strong and weak points in the design.

- Building for Life 12 – applicable to residential schemes, Building for Life produces a score out of 12 for the quality of place that a scheme promotes.

These consultations make take the form of relatively short presentations, longer exhibitions or workshops around specific interest groups. Such events can appear time-consuming when developing the Design Programme, but they do contribute considerably to the completeness of the Developed Design, informing the review of Project Strategies for subsequent stages, and therefore often save time resolving incomplete design thinking later on when there is less design flexibility. Avoiding pressure to resolve design matters in later stages also benefits the quality of the design, as decisions are made with appropriate information and time to consider options.

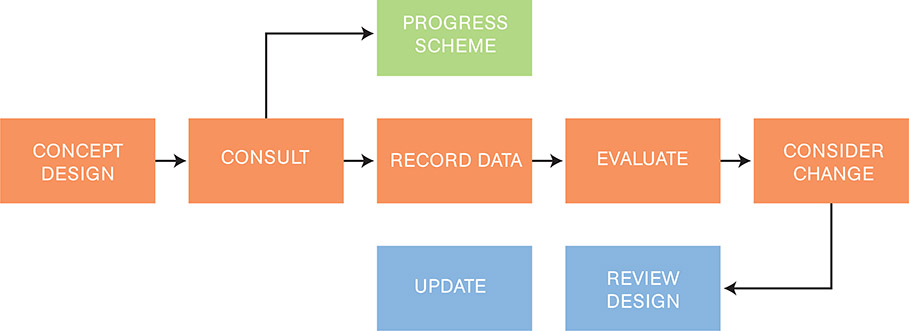

3.6

A process map for third party consultations.

Examples of Third Party Consultations

The following bullet points provide a brief illustration of some of the types of consultation events that even a modest building project might benefit from. Clearly, some of these events can relate directly to the continual review of specific Project Strategies and inform the stage-completion Information Exchanges of these. Examples of consultee organisations are given in each case.

- A user group representative of the people who will use the building and who have specific requirements that need to be catered for. This group might meet three or four times during the design process in order to share needs and provide comments on designs as they evolve – eg a tenants’ association development subcommittee.

- A special workshop event with the whole project team represented in order to review accessibility issues – not only from a statutory-compliance point of view, but also with regard to whether any of these issues form part of the ‘identity’ of the building or a particular service that the client wishes to promote from the new premises. Some projects will have an accessibility consultant, who will lead on this aspect of the Developed Design stage (accessibility strategy) – eg the Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB).

- A design workshop with relevant design team members and client end user or facilities management representatives, if appointed, on maintenance and plant-replacement strategies; maintenance regimes, as far as they are understood; and contract cycles (Maintenance and Operational Strategy) – eg the appointed building caretaker or facilities manager.

- A design scenario workshop with relevant design team members and client end user or facilities management representatives, if appointed, to review how all daily operations, including reception function, will work; communications equipment and data installations; ‘first in/last out’ security sequence and protocols for alarms, including personal-safety issues that might arise from after-hours working; CCTV and other security installations, including car-parking arrangements and the protocols and requirements of fire drills and evacuations; and protocols for alarm performance in relation to external and emergency services (Operational Strategy). There should be an opportunity for the comments and requirements recorded by the first of each of these design workshops to be illustrated within the design context and relayed back to the group for further comment – ideally, if time permits, within the Stage 3 Design Programme – eg the security contractor; the Secured by Design Architectural Liaison Officer (ALO), a member of the local police force who advises on security in designs.

- A public consultation can take the form of an exhibition or a more interactive event. The aims of the consultation should be discussed and agreed with the project team before the event. Comments and observations should be encouraged via an easy-to-use method, but it should be clear to members of the public attending how the client and design team intend to respond to their comments. How is feedback going to be delivered? Is there a publicity opportunity for the future project, of which this public consultation can form a part? What should the interaction with local ward councillors, planning committee members and officers, and other statutory consultees be at this stage? The planning application and the procedures that lead to a determination of that application are embedded in local democratic processes, and there is a need to understand – particularly in relation to controversial schemes or land-use proposals – how best to frame the supporting arguments for the project against the potential for, and content of, objections throughout the application period. Public consultations held prior to a planning submission can often act as a test ground for these opposing arguments – eg the developer, local councillor(s), residents’ associations.

In the context of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013, it could be relatively easy to underestimate the powerful outcomes from a properly planned and executed consultation programme. Timely consultation of interested third parties creates a constructive working relationship, and informs the design process before the stage at which consultee input might create abortive work. On the other hand, a thoroughly worked-through Design Programme naturally seeks comment and critique on evolving design issues, and these opinions inform both the design process and the criteria that will eventually govern the building project becoming a success or not.

Consultation related to planning

Earlier in this chapter, reference was made to public consultation or engagement events held prior to a planning submission. It is also worth noting briefly the consultations that take place during a planning application period. Town and country planning legislation has embodied within it a statutory public consultation period of 21 days. This is notified on site, and gives any objector or supporter of the scheme an opportunity to make written representation to the planning authority – usually the local council but some areas are covered by a special authority, for example one of the UK’s National Parks.

The same period is used for what are known as ‘statutory consultations’ with bodies such as the Environment Agency, Historic Scotland, Cadw, Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) or English Heritage, Natural Resources in Wales, Scottish Natural Heritage, NIEA or English Nature, who have the opportunity to say whether the proposed development scheme impacts on their jurisdiction or apparatus. Internal council consultees are also formally approached for comments; these will include departments such as Highways and Transportation, Environmental Health and Landscape, but may also involve other specialisms like conservation or the tree officer. This is a formal process as part of planning legislation, and is not discursive or exploratory in nature. If pre-application advice has been taken, it is likely that all the statutory and internal consultees will have already commented; however, once the planning application is registered there remains the opportunity for all comments received to influence the design before a permission is granted.

What Format Does Cost Information: take at Stage 3?

A design team that understands the cost of construction and maintains an interest in developing Cost Information is well placed to complete Stage 3 with a design that remains within cost parameters, and with suitable design development allowances for Plan of Work Stage 4 Technical Design. Cost Information during this stage will inevitably rely on historical elemental cost data for construction types. This will produce a ‘Construction Cost’ estimate, and to complete the cost plan the cost consultant will use industry-standard indexed predictions on cost inflation for materials and labour, together with project-specific contingency sums against known project expenditure (for example, furniture and fittings) and some general contingency sums for possible future discoveries.

Cost Information at Stage 3 is usually presented as showing the main elements of the building (eg substructure, superstructure, building services). These elements will have varying levels of detail behind them, depending on the nature of the project and the extent of research undertaken into the cost of building components and products as described earlier. The level of cost detail gathered from design workshops, product manufacturers and other cost data will be variable, and the design team must work together to provide the best possible cost-planning information. Where detail of certain elements is less robust, the lead designer should work closely with the cost consultant to make certain that the contained in estimate allowances are realistic and appropriate.

3.7 Types of cost data set up in a tabular form for cost planning.

Designing to cost at Stage 3

Cost is always going to figure as a high priority within the project criteria set out in the Initial Project Brief. The relationship of cost to the remaining two prime components of a project, time and design quality, will dictate some of the sequencing of tasks during Stages 2 and 3. Designing to cost has been discussed in the previous chapter, and in Stage 3 the relationship between design and cost is critical in delivering a robust Information Exchange that the client can have confidence will deliver their project to cost with the design quality illustrated at this stage.

The Importance of Sustainability: running throughout the project

Task Bar 6 on the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 makes provision for a sustainability checkpoint at each stage. Every building project will have a set of sustainability matrices mapped out at the Initial Project Brief stage, which will be measured during progress. Some of these may be funding requirements, client targets or external stakeholder provisions that need to be met. It is important to distinguish between those external goals and aspirations set out to allow the project to be realised from those that may be best-practice goals for the construction industry, personal or team targets or innovation targets, which do not have a bearing on whether the project proceeds. These two things though do come together to form the Sustainability Strategy.

It has been clear for a number of years now that new building projects have a substantial contribution to make to UK and global carbon-reduction targets, along with other environmental targets on resource usage. There are many ways of a project achieving a meaningful contribution to a sustainable future, and at the Stage 3 Information Exchange the methods committed to and means of achieving these targets need to be embedded in the design and cost information.

Stage 3 Sustainability Checkpoints from the Plan of Work ask:

- Has a formal sustainability assessment been carried out? If it has at an earlier stage, has it been reviewed during Stage 3?

- Have an interim Building Regulations Part L (conservation of fuel and power) assessment and a design stage carbon/energy declaration been undertaken?

- Has the design been reviewed in order to identify opportunities to reduce resource use and waste, and the results been recorded?

Establishing a Sign-Off Protocol: for Stage 3 completion

Under an earlier section of this chapter, the possibility of Stage 3 being the end of a commission was discussed. It is important to also recognise the prospect of a significant time lapse occurring between the completion of Stage 3 Developed Design and the beginning of Stage 4 Technical Design. The reasons for this sort of delay may be attributable to general economic conditions, project funding procedures, occupancy of the existing site or building, or the planning process itself. The particular reason is far less important to the smooth running of the project than the ability of the design team to present all the design information gathered and produced during Stage 3 in a style that is both easily understandable and accessible in the future. This is the role of the Information Exchange, Task Bar 7 of the Plan of Work. The completed Developed Design, collated with all relevant information for the stage, should be organised so that it can be picked up, understood and immediately built upon at the commencement of Stage 4 Technical Design.

One of the reasons that this Information Exchange needs to be comprehensive is that individuals within the design team inevitably become embedded within the design development process, and carry a lot of quick-access knowledge about the project while working on it. Over the course of the time delay between stages, project staff may have changed projects within a practice, changed employment or otherwise be unavailable to use their retained knowledge to assist at the start-up of the subsequent stage. If they are still employed at the same practice, it may, of course, be possible to elicit some knowledge from an internal, discreet ‘handover’ meeting. However, this opportunity should not be relied upon, and in any case the written documentation made at the time of completion is going to be more reliable than the recall of individuals.

A good way of achieving this aim is to ensure that the stage completion information fits the following criteria:

- A narrative that illustrates the original conceptual intention, in order to avoid misinterpretation or loss of the Concept Design.

- Clearly drawn or modelled information with key dimensional data displayed. Each design team member will have the following information as a minimum:

- ~ Architect – site layout; dimensioned plans, sections and elevations; some relevant larger-scale details to illustrate design intent; specification notes for all works.

- ~ Structural engineer – structural grid and structural member sizes, foundation type and layout, underground drainage layout, specification notes for all works.

- ~ Building services engineer – plant room layouts; distribution routes, sizes and equipment; heat and lighting layouts; ‘Part L’ energy-use model and calculations; specification notes for all works.

- ~ Landscape architect – site layout, planting schedule, specification notes for all works.

- A BIM project should include a coordinated model with all the above integrated into a single model.

- Updated Project Execution Plan and Project Strategies.

- Cost Information related to the outline specifications above.

- A Project Programme demonstrating how time has been allocated to future Plan of Work stages.

- If necessary due to a break in programme, an explanatory narrative illustrating how final design decisions were arrived at, in order to avoid loss of project knowledge from any personnel change.

- An easily referred-to log of final decisions in the Project Strategies.

The Information Exchanges at stage completions require the discipline of design team members in order to provide good-quality Project Information in a timely and presentable manner. At Stage 3, this involves developing the project with well-considered and reviewed strategies; a fully coordinated design, with researched and confirmed Cost Information; and having a mechanism, as part of the Project Execution Plan, to allow a check against the Initial Project Brief. This should result in a successful project delivering excellent design standards.

As at Stage 2, the project team should consider the requirements of a UK Government Information Exchange if it is relevant for the project.

What Should be in the Information Exchange: at the end of Stage 3?

As just described, when the tasks in a stage are completed the design team prepares an Information Exchange for handing to the next stage. At Stage 3, this is a particularly important point in the project when the overall design ‘feels’ complete. The client signs off the design so that a planning application or tender process can commence. The Information Exchange at the end of Stage 3 Developed Design should include the following:

- Design information from all design team members. As noted earlier, this might include appropriately scaled and dimensioned plan, section and elevation drawings; photomontage illustrations; 3D electronic and physical models; a document detailing the site analysis, context and design constraints; and an appropriate level of specification detail relevant to the procurement route. The level of detail in a BIM environment should be sufficient to allow full coordination between architecture, structure and building services:

- ~ establish main site and finished floor levels in relation to existing site levels

- ~ detail main structural grid and principal plan and section structural dimensions

- ~ detail main plant and equipment room requirements

- ~ detail main service zones and distribution routes and how interface with structure is working

- ~ detail building services external envelope penetrations

- ~ detail main external wall and roof build ups

- ~ detail all internal wall, floor and ceiling types and finishes

- ~ detail door and window openings

- ~ detail main external works elements.

The coordinated design must be reflected in the Cost Information.

- The procurement strategy. The procurement route will be determined and embedded in programme information, and reflected in the Project Execution Plan. The procurement strategy will detail the information relevant to the chosen route, and this will form part of the Stage 3 Information Exchange.

- A Project Programme, showing the time period allowed for the remaining stages of the project.

- A Design Programme coordinated with the Project Programme, showing the proposed sequence and level of detail required during Stage 4 Technical Design.

- The Project Budget. This should include a construction cost plan and be clear about what is included and what is not. The cost and design must be aligned.

- Planning information: Details of the planning submission and a status report. Planning permission may be a prerequisite to starting Stage 4.

- Health and safety implications. These will have been considered, risks mitigated where possible by the design team, and a residual risk register prepared.

- All Project Strategy documents. These key strategies will cover Sustainability, Maintenance and Operation, Handover, Construction and Health and Safety.

- The Project Execution Plan will have been updated, and Change Control Procedures will be in use.

If during Stage 3, or earlier in some projects, it becomes a requirement to complete the building as fast as possible, the design team must immediately consider what the impacts on Information Exchanges are likely to be. As in our Scenario E, it is possible to conceive a Project Programme that overlaps the end of one stage with the start of the next. Additional diligence is required in progressing from Stage 3 to Stage 4 without a fully resolved design, as this increases the risk of coordination issues arising before or during the construction stage. Using the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 as a tool for mapping the sequence of tasks, even if overlapping, will promote good project management in this pressured situation.

Emerging Digital Information Types

A number of digital technologies are becoming influential in architectural practice as extended tools to explore concept designs and diversify the range of Information Exchanges. Many will be used during Stage 2 but arguably they will be most adeptly utilised during Stage 3. Some of these technologies might include

- Enhanced virtual realities and immersive environments where physical and sensory experience of the project design becomes a possibility

- 3D printing from simple 3D or BIM models – exploring building components, parts of or whole buildings. Relatively quick and easily set into context 3D printing

- Parametric design allowing software to create architectural form with given data sets for the programme or setting of the project

- Architects are becoming coders and scripting elements of the digital design toolbox to create unique approaches and identifiers within their designs

- Improved visualisation techniques and software design for photo-real CGI

Digital technologies are forecast to continue changing the design team toolbox at a very rapid rate, so while the processes behind the design will conform to the Plan of Work framework the outputs will continue to help the design team provide more accurate information.

Chapter 03

Summary

- At Stage 3, the design becomes more detailed, accurate and coordinated with the outputs from the design team. The design will be clear in its scope and backed up by information that demonstrates that it is achievable within the project parameters set.

- The lead designer develops and manages the Stage 3 Design Programme, and reviews what is required during Stage 4.

- The design team reviews and updates all Project Strategies as necessary.

- The Project Programme and Cost Plan are reviewed and updated.

- The Project Execution Plan is reviewed and updated, adding Change Control Procedures if they have not been included at an earlier stage.

- A planning application is prepared and submitted, unless it has been previously agreed that it should be submitted at Stage 2. The design team should be aware that this action puts the project into the public realm for possibly the first time.

- A comprehensive and clear Information Exchange is prepared for the completion of Stage 3. A delay between stages or a change to the design team personnel is most likely at this point, and it is essential to the integrity of the project that the Developed Design translates successfully to Stage 4.

Scenario Summaries

WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO OUR PROJECTS BY THE END OF STAGE 3?

A Small residential extension for a growing family

The architect and structural engineer have completed a coordinated design for the residential extension. Taking the architect’s advice, the client agreed to attend a series of pre-application meetings with the planning authority, which has allowed a planning application to be prepared taking on board a number of statutory-consultee comments. The planning application submission to the local authority forms part of the Stage 3 Information Exchange, and will be submitted via the online Planning Portal (www.planningportal.gov.uk).

A simple 3D block model has been developed in sufficient detail to be able to generate photomontage street views and garden views, in order to address client concerns about impact on neighbours and to accompany the planning application. The client has no interest in how the information for the project is produced in Stage 4 and recognising the limited coordination benefits for this scale of project in using a building information model the design team have decided to produce 2D information due to the tight timescales.

The architect has spent a lot of time during the Stage 3 Developed Design process discussing the relative merits of a number of external wall, window and roof materials, and a full spectrum of internal finishes too. Because the external materials are important for planning permission, the client has considered longevity, repair and replacement alongside appearance, and a detailed log of these choices has led the architect to instigate a research project on regional brick patterning, coursing and detailing. This has helped to assure the planning authority that the quality of detailing in the project will be very high.

The architect has advised the client that with a traditional procurement route the tender information needs to be fully detailed to avoid cost uncertainty or additional cost by late introduction of information or changes of design. In addition, the architect has expressed a concern about the client’s Stage 1 decision not to appoint a building services engineer on the design team when a significant amount of services information was generated by the Final Project Brief and the client’s Sustainability Aspirations, which will be requiring detailed Stage 4 information in order to assemble a robust tender package and pre-tender cost estimate. Following discussion, it is agreed that a services engineer can be appointed to close out Stage 3 and produce tender information at Stage 4.

The Project Programme has been revised at the end of Stage 3 to allow for minor delays during the pre-application process. Now that the Detailed Design is nearing conclusion the length of time needed to produce a comprehensive tender package is clearer, and the client is keen that Building Control full-plans approval is received before going out to tender. Although this produces a construction start four months behind that originally hoped for, the client’s main driver is quality of the build and, as they intend to stay in the house during construction, no particular dates are placing pressure on the programme.

B Development of five new homes for a small residential developer

Planning permission was achieved at Stage 2 and, as the architect had advised, there were a greater number of planning conditions than normally expected. While progressing the Stage 3 Developed Design, the architect has had to resubmit elements of the design for minor amendments, and this has been able to ‘capture’ some of the conditioned information at the same time.

The developer has continued to drive down the budget for the scheme through amendments to the specification, and, while preferring a traditional contract, has indicated that they want to be on site at a point in the Project Programme much earlier than the design team can complete a robust tender package for this sort of contract. As the scheme is residential, the developer is prepared to work from their own historical data to create cost information that reflects the essential internal detail (joinery details, kitchens and bathroom fittings, etc.) and to include provisional sums against these items, allowing the design team to focus on the envelope design.

The lead designer, the architect in this project, has expressed reservations about this curtailed programme, but understands that this pressure comes from the way the project is financed and the desire for early sales revenue from the scheme.

The design team have prepared outline specifications and general-arrangement technical design in order to allow a Building Control submission. The client is only interested in achieving minimum regulations, but a Sustainability Strategy has been prepared to allow an initial ‘Part L’ model to be produced and to demonstrate how a ‘Fabric First’ approach to the design and careful orientation on the site contribute to the benefit of the occupants. The design team have convinced the client that lower energy bills and the beneficial use of solar heat gain can be used as sales incentives rather than being seen as unnecessary costs.

C Refurbishment of a teaching and support building for a university

The client’s financial appraisal of the Stage 2 Concept Design supported the inclusion of the additional teaching space created by efficient space planning during the Concept Design stage. Despite the scheme costing a little more than envisaged the revenue return exceeds the additional borrowing costs. The Final Project Brief has been adjusted accordingly.

As highlighted at Stage 2, the design team’s appointment finishes at the completion of Stage 3. The client’s intention had been not to commit beyond known funding support. Although this has now been received for the completion of the project, the project lead is still developing the procurement strategy with the client and no decision has been made in respect of whether the design team will be novated to the design and build contractor or not.

The design team have prepared the Stage 3 Information Exchange as for a single-stage design and build tender package, and this includes aspects where specialist subcontractors will have design responsibility, relevant Project Strategies, a risk register and a schedule of tasks, in the form of a Design Programme, to be completed during Stage 4 Technical Design by the contractor’s design team. This last-named document was produced due to the uncertainty around the contractor’s eventual design team. The Design Responsibility Matrix has been updated to include all the contractor’s design responsibilities and to clarify how specialist subcontractors will contribute to the Stage 4 Technical Design process.

Also included with tender documents is a schedule of investigative surveys to open up the existing fabric, so that the contractor and their design team will have this information to establish a coordinated design. These surveys are to be costed as part of the contract, and provisional sums used against items of work that will be confirmed once surveys are complete. The items are recorded on the risk register, and the design team have highlighted to the client that there is a significant cost risk attached to this methodology. Because of the considerable uncertainty at Stage 3 completion about exactly which way the design will be continued, the rather brief Communication Strategy from Stage 1 has been significantly enhanced in order to ensure that lines of communication between the eventual parties to the contract are well understood and easy to use.

D New central library for a small unitary authority

During Stage 3, the client’s design team have worked with the contractor’s design team in a series of design, risk and operations workshops. Adherence to the initial Project Objectives was key to these workshops, and participants thought that they were a great success in delivering a comprehensive Stage 3 Information Exchange. The contractor has made significant contributions to the buildability of the scheme as part of the Construction Strategy, suggesting prefabricated elements of envelope construction, and, as a result, is offering an appreciable reduction in the Stage 5 Construction period of the Project Programme.

The two-stage design and build contract is in the last round of negotiations on lump-sum price, and the client’s and contractor’s design teams have agreed the Stage 4 Technical Design Programme. There are no changes to the Design Responsibility Matrix for this stage. There is a small amount of concern that the levels of risk contingency allowed in the lump sum are too high given the amount of early site investigation work that already exists. Negotiations between the client, cost consultant and contractor resolve this matter.

The BIM execution plan for Stage 3 is completed by the BIM manager (the client’s architect on this project), and the protocols are accepted by the contractor’s design team. The contractor during Stage 3 has developed their own BIM capability, and is planning on using the project as a pilot for how BIM can streamline their programme reporting – particularly around 4D (time) information and linking the model to the Construction Programme. Some additional fees have been agreed with their design team to help facilitate this task.

The Stage 3 Information Exchange includes a comprehensive Developed Design report that, subject to agreement on the contract sum, has been signed off by the authority. While an outline specification would normally be agreed by the client’s design team at this stage, the fact that there has been a collaborative working relationship means that the contractor has confirmed 80% of the proposed materials and finishes – and this has assisted in cost planning.

The agreed Project Programme requires a Building Control application to be made as soon as Stage 4 begins, in order to allow commentary and changes to be absorbed within the Stage 4 Technical Design Programme. As the contract will have been let by then, the contractor’s internal Change Control Procedure has been established to ensure documentation and correct approvals for any proposed changes.

E New headquarters office for high-tech internet-based company

The management contractor has prepared a Construction Programme and a procurement strategy. The immediate impact on the Stage 3 Design Programme was to identify and begin assembling work packages to be tendered as soon as they are ready. The principal reason for choosing this form of contract was to allow work to start on site at the earliest opportunity, as the client has witnessed unprecedented growth during the previous six months and needs to be able to occupy their new headquarters as soon as possible. Out of approximately 15 work packages, the first two – substructure and concrete frame – are already out to tender, and a start on site is expected before the conclusion of Stage 4 information in other packages.

The client signed off the design at the end of Stage 3, and it has been submitted for planning permission. The client is aware of the risks involved in allowing Stage 4 design work to commence before approval is granted, but feels confident that consent will be granted and is willing to accept the risk.

The management contractor has produced a Stage 3 cost estimate for the project that is within +3% of the Project Budget. Some market testing has taken place in order to inform this cost, and a target price has been incentivised by the client. The Design Responsibility Matrix has been updated to reflect the complexity involved in multiple work packages, in particular highlighting where responsibilities lie at various package interfaces in order to avoid conflict later.

The Handover Strategy has been developed in detail during Stage 3, as the client wishes to undertake their own IT fit-out with various specialist equipment installations before Practical Completion. Partial possession is also being considered, to allow early occupation of up to four months before Practical Completion of almost a third of the building. The company is growing so quickly that the client has also broached the subject of adding a 30% floor-area expansion of the building to the contract if it is at all possible without causing delay to the main building. The CM and design team have quickly assessed this new prospect, and it has been decided to seek planning permission before the end of Stage 4 of the existing project – adding the additional work in work packages by way of a variation, and attempting to bring the whole project to Practical Completion at the same time. The Design Programme, Project Programme and Handover Strategy have all been updated to include this new aspect of the project.