2

![]()

Group Decision Making and Group Effectiveness in Organizations

Richard A. Guzzo

Bridges are popular metaphors. We hear how a political candidate is a bridge between the liberal and conservative factions of a political party, for example, or how an airline's frequent flights create an air bridge between two cities. I, too, will use a bridge metaphor to introduce the content and aims of this chapter. In particular, a suspension bridge serves as a useful metaphor. A suspension bridge is a structure that connects distinct areas by hanging a platform (such as a roadway) from two or more cables that stretch beyond the platform itself. With the platform secured we can get to places we otherwise would have difficulty reaching.

This chapter seeks to construct a platform, not of concrete and steel but of ideas and concepts useful for getting us to new places in theory, research, and practice with regard to decision-making groups in organizations. The two cables supporting the platform are the bodies of research and theory on (1) group decision making and (2) group effectiveness in organizations. As is true for a suspension bridge, the value of the platform depends on the strength of the supporting cables. And those cables are not unchanging entities: They rise, fall, sway, and stretch. Thus, changes in research findings or theory can be accommodated. That the cables outdistance the platform itself suggests that these bodies of theory and research have a history and future that surpass the life of the ideas presented in this chapter.

A final comment about a suspension bridge as a metaphor for the work of this chapter is necessary. One meaning of the word suspension refers to keeping something fixed to await the information and consideration needed to evaluate it. This chapter will present some ideas and propositions that, although derived from prior knowledge, are not yet tested. Thus, they hang suspended until further data are collected.

Presented first in this chapter is the meaning of decision making and implications of its definition for understanding groups in organizations as decision-making bodies. Next, various issues about the nature of group decision making in organizations are illustrated through an examination of some typical decision-making groups in organizations, quality circles. Existing theoretical frameworks of group effectiveness are then reviewed for their relevance to the understanding of group decision making, leading to a consideration of conditions that improve the effectiveness of decision-making groups in organizations. Last, some thoughts on impending areas of concern to research and theory are offered.

Decision Making Defined

Decisions are commitments to action, and decision making is defined here the way Herbert A. Simon, winner of a Nobel prize for his work on decision processes in organizations, defines it. According to Simon (1977), decision making is made up of four kinds of activity: intelligence, design, choice, and review. Simon's is a realistic, broad definition of decision making that provides the opportunity to learn a great deal about the effect of various factors on group decision making and sources of effectiveness.

The intelligence phase of decision making is concerned with recognizing occasions calling for a decision. The term intelligence is used here in the military sense of monitoring and gathering information that can be analyzed for its meaningfulness. In organizations, occasions calling for decision might be routine and familiar or dramatic and unpredicted. Routinely, for example, decisions are made about matters such as allocating employees to jobs and the purchase of a vendor's goods. Suddenly appearing occasions calling for a decision might be a competitor's marketing a new product or a rapid deviation from quality standards in a production process.

There are infinite numbers of occasions calling for decisions, some more easily recognizable than others. Few people fail to recognize the need for decision making when a crisis occurs, and most are well aware of chronic problems that interfere with work and call for some decision to be made to alleviate those problems. Perhaps the most difficult-to-recognize occasions for decision are what Mintzberg, Raisinghani, and Theoret (1976) call opportunities. These are situations that permit decisions to be made when there is no threat or trouble, decisions that can improve an already satisfactory state of affairs. For example, circumstances may arise that Call for a decision to change compensation practices in an organization, not because of a crisis (for example, a strike) or a problem (for example, unwanted turnover), but because a change in rulings by the Internal Revenue Service make new means of compensation preferable to old for both the organization and individual employees. The intelligence phase of decision making involves determining when decisions ought to be made in response to a wide variety of circumstances.

The second phase of decision making, design, is concerned with creating, developing, and assessing possible courses of action. Design activities yield alternative courses of action for consideration. In some instances of decision making the time spent on design may be brief because the alternatives are limited, such as go or no go. In other instances, though, this phase may be quite extensive, such as when designing alternative solutions to unfamiliar problems. Once alternative courses of action are identified, the third phase of decision making, choice, becomes operative.

Choice activities refer to the process of selecting one course of action from those specified in the design phase. It is this phase of decision making that has received the greatest amount of research attention. In fact, many investigators define decision making in terms of choice only (Nutt, 1976) and others offer multiple descriptions of and prescriptions for making choices, especially by individuals (Einhorn and Hogarth, 1981; Svenson, 1979). Choice is but one phase of decision making in organizations, and it is the third of four phases described by Simon (1977).

The fourth phase of decision making is review. Activities in this phase involve monitoring past choices both to see if chosen courses of action are properly implemented and to determine if new decisions must be made. Review activities close the cycle of phases in decision making: Reviewing past choices is, in part, a reinitiation of the intelligence activities that are a part of all decision-making episodes in organizations. Note, though, that not all intelligence activities are prompted by the review of past choices.

Relations Among Phases of Decision Making. The phases of decision making are discernible but loosely bounded. Designing alternative courses of action may go on at the same time that data-gathering intelligence activities occur, for example, and examination of available courses of action in the choice phase may bring about an awareness that new alternatives must be formulated. Although in a general way intelligence precedes design and design precedes choice (all of which precede review), there exists neither a necessarily orderly progression through the stages nor a set of markers that differentiate one phase from the next (Alexander, 1979; Simon, 1977). Further, each phase also can be thought of as a microcosm of the complete episode of decision making. Decision-making episodes are often best thought of as wheels within wheels within wheels (Simon, 1977), such as when decisions are made during the intelligence phase about what facts are to be regarded as important. Decision-making episodes in organizations must therefore be regarded as complex, even messy, however difficult such regard makes the task of studying decision making.

It is now widely accepted that most organizational decisions are not made in a perfectly rational way. That is, incomplete information search, imperfect logic in the design of alternatives, and nonoptimal selections among alternatives occur. The definition of decision making presented here in no way implies that decisions are truly rational.

Decision Making as a Group Task. The variety of tasks worked on by groups has long received attention in social psychological research on group performance effectiveness. Most of this research has not directly concerned groups in organizational settings.

An excellent overview of theory and research on group tasks is provided by McGrath (1984). As McGrath recounts, early distinctions among group tasks were relatively straightforward, such as distinctions between intellectual and motor tasks and between simple and complex tasks. As time passed, distinctions became more detailed and varied. For example, Carter, Haythorn, and Howell (1950) discussed six types of group tasks: clerical, discussion, intellectual construction, mechanical assembly, motor coordination, and reasoning. Shaw (1973), through a multidimensional scaling analysis, identified six dimensions on which group tasks vary: intellective as opposed to manipulative requirements, task difficulty, intrinsic interest, population familiarity, solution multiplicity, and cooperation requirements. Hackman (1968) also adopted an empirical approach to the description of “thinking” tasks and identified three types—production, discussion, and problem solving—for which solutions were seen to vary in identifiable ways, such as in originality and action orientation. An often-cited typology of group tasks is Steiner's (1972) distinction between unitary tasks (those that require the combination of group members' outputs into a single product) and tasks that can be divided among members. Unitary tasks were further described as being disjunctive (the task can be completed by any one member of a group), conjunctive (the task can be completed only by having all members of a group perform it), additive (members' contributions are summed to fulfill the task), and discretionary (the task can be solved through a variety of ways of combining members' inputs). A final example of the analysis of group tasks is Laughlin's (1980) classification of intellective and decision tasks for groups whose members pursue the same goal as opposed to competitive and bargaining type tasks for groups whose members pursue divergent goals.

From the lengthy list of existing descriptions of group tasks a few organizing principles were distilled by McGrath (1984). McGrath suggested that two basic dimensions of group tasks underlie existing descriptions. One dimension is the presence of conceptual, as opposed to behavioral, demands of tasks, or “thinking” as opposed to “doing.” The second dimension is the degree to which a task induces conflict as opposed to cooperation among group members. Further, McGrath suggested that four general categories of action (or group process) occur during the performance of a task: generating, choosing, negotiating, and executing. From these organizing principles, McGrath classified descriptions of group tasks into eight types and used these types to review and discuss results of research on group performance.

I believe that McGrath's account is an accurate portrayal of most existing descriptions of group tasks but that it does not adequately describe group tasks as they occur in organizations. The reason concerns how group tasks and task performance typically have been studied: The predominant research method has been laboratory investigation. This method of investigation limits in many ways the nature of tasks open to investigation, such as restricting tasks to those of short duration, comparatively low complexity, and one-shot as opposed to cyclical performance requirements.

The complete task of decision making, for example, is rarely captured in laboratory studies. Most such studies examine what transpires after a group has been told that a decision must be made, precluding from study the intelligence phase of decision making. Similarly, laboratory studies of decision making often end abruptly once a choice among alternatives is made, giving little attention to the role of review in decision making. (For an example of a laboratory study of decision making that ignores intelligence and review activities, see Guzzo and Waters, 1982). Consequently, typologies of tasks derived from the laboratory study of groups are not fully applicable as descriptions of group tasks in organizations because of the comparatively greater variety in tasks performed by groups at work.

In no way are the comments made here to be construed as a general argument against the value of laboratory research on group task performance. On the whole, laboratory research has given considerable insight into several aspects of group task performance, including insight into two of the four phases of decision making. However, descriptions of group tasks based on what groups do in research laboratories are likely to be impoverished when applied to groups in organizations.

Quality Circles: An Illustration of Group Decision Making

It is useful to examine group decision making in organizations in concrete terms. While there are many ways in which to do this, an examination of quality circles (also known as quality control circles) as decision-making groups is especially instructive because of the highly visible, systematic manner in which their decision making occurs.

Quality circles are an innovation in workplace practices that emphasize groups as important units in organizations. Interest in quality circles in American organizations began in the mid to late 1970s, partly in response to what was widely believed to be the instrumental role played by quality circles in making Japanese organizations successful. It is ironic that quality circles were in fact an American invention that found domestic acceptance only after another country implemented them on a large scale (Cole, 1979).

Quality circles generally are groups of five to ten workers who perform similar jobs. Membership in the quality circle group often is voluntary and group meetings are held regularly. The meetings may take place during or after work hours. A leader is usually designated for each quality circle, typically the first-level supervisor, although in some quality circles the leadership role is rotated among members or may be filled by nonsupervisory personnel. The leadership role is a special one, requiring skills as a discussion moderator and facilitator of meetings.

There are many objectives to be served by the establishment of quality circles, such as increasing workers' commitment to the organization and job satisfaction. A principle objective, as the name suggests, is to resolve problems that concern the quality of production or service in an organization, although problems of quantity of output, safety, and other matters also are addressed in quality circles. To aid these groups in their work as quality circles, members are trained in a method of tracking information through devices such as Pareto diagrams, cause-and-effect diagrams, graphs, histograms, scatter diagrams, and other statistical displays. Members also receive training in communication skills and brainstorming techniques.

Organizations invest in quality circles significant responsibility to make and implement decisions about work procedures that have a bearing on productivity. Whereas the responsibility for such decision making might previously have resided with the quality control department in an organization or levels of management above the workers, the use of quality circles moves that responsibility to groups of workers who themselves perform the basic tasks of the organization. While many interesting issues can be raised concerning the impact of quality circles, for present purposes they are discussed to illustrate dynamics of group decision making.

Much time in quality circle meetings is spent in the intelligence phase of decision making. Training in statistical analysis and display of information facilitates the group's work in this phase as the group seeks to identify those circumstances calling for a decision. Most often those circumstances are in the form of problems (of wasted resources, defective products, time inefficiencies), but the group also has the capacity to recognize opportunities for new actions that may help performance without necessarily solving a prior problem. Through quantitative and diagnostic displays of patterns of defects, scrap rates, quantity of output, accidents, and other data, quality circle procedures make explicit much of the information needed by a group to determine whether the next phases of decision making, designing alternative courses of action and choosing among them, need to be initiated.

The design phase of decision making in quality circles is a direct extension of the intelligence phase. In design, group members construct alternative ways of solving an identified problem, for example, or implementing a new idea. Brainstorming procedures often are used during this phase as a means of developing a broad range of alternatives. Proponents of quality circles suggest that the real value of quality circles is to be found in the design phase of decision making because the people who know best how to solve problems on the workfloor are those closest to the work: the workers themselves, not management or a removed quality control staff. Said another way, quality circles have the proper group composition for generating solutions to a problem.

The third phase of decision making, choice, is less patterned than design or intelligence. That is, quality circles are not necessarily instructed that their selections among alternative actions must reflect unanimous consent, majority opinion, or any other means of committing the group to an action. Variability among quality circles exists in how choices are made. Choices made by quality circles may or may not require the approval of management prior to implementation.

The final phase of decision making in organizations is review. In quality circles this phase is facilitated by the regularity of meetings and standardized methods of tracking and displaying performance information. In fact, in quality circles the activities of review blend easily with those of intelligence.

This account of quality circles is presented to illustrate how the four phases of decision making apply to groups as decision makers in organizations, although the account undoubtedly presents decision making in groups in too orderly a fashion. Most quality circles are likely to jump from one decision problem to another, to be interrupted, to cycle back and forth between phases of decision making, to undergo changes in membership, and to experience any number of things that make the decision process more complex. Further, quality circles are not just decision-making groups. They are groups that, in McGrath's (1984) terms, execute. That is, they physically apply themselves toward the completion of the duties inherent to their jobs in the organization. Quality circles might also serve as a vehicle for socializing individuals in organizations. While quality circles are good arenas to examine group decision making, it is important to recognize that their decision processes occur in a busy context.

In addition to quality circles, there are many other quarters in organizations in which group decision making occurs. These include committees, task forces, top management teams, flight crews (Foushee, 1984), and the highest levels of policy making in government (Janis, 1982). Janis provided a number of case studies of defective decision making attributable to what he termed “groupthink,” a syndrome characterized by a deterioration of thinking and judgment among group members. The symptoms of groupthink and its consequential defective decision making include poor information search, incomplete survey of alternatives, and failure to examine the risks associated with the preferred alternative. These symptoms are interpretable as errors occurring within the framework of the intelligence, design, and choice phases of decision making.

General Models of Group Performance

Thus far decision making has been considered as a group task, one of many tasks that groups perform. Past research and theorizing has generated a number of models of group task effectiveness meant to apply to groups performing all sorts of tasks, such as laying pipe, delivering health care, or playing basketball. Consideration of such general models of group performance effectiveness can help identify causes of effectiveness specific to the task of decision making. The following section reviews some general models of group effectiveness in order to draw from them an understanding of determinants of effective group decision making.

Steiner's Work. Steiner's (1972) model of group performance integrated much previous social psychological research on group effectiveness. There is a deceptively simple quality to the model's assertion that actual group productivity equals its potential productivity minus losses due to faulty group process. The true complexity of the model stems from the role played by Steiner's group task typology described earlier.

Potential productivity refers to the maximum level of competence on a task that can be expressed by a group when the group possesses, and can apply, the resources required to complete the task. Depending on the situation, maximal competence might be defined according to speed, accuracy, or some other criterion. Resources include information, experience, skills, and tools available to group members. Note that the distinction between available and applied resources indicates that although a group may have the capacity to perform well, it will not necessarily utilize those resources appropriately. Inappropriate utilization of resources, in Steiner's model, is due to process losses. Process refers to all possible behaviors occurring in a task-performing group, including both task-oriented and purely social behaviors, and some group process may prevent the optimal combination of a group's resources for task completion.

How a group's resources should be combined is determined by the nature of the task, according to Steiner's model. For example, a task may demand that members' resources be summed for maximal performance (as in a group pulling a heavy object), or a task may demand that no more than one member's resources need be applied to the task (as in a group solving a riddle). The former is an example of an additive task, the latter a disjunctive task. Process losses, the impediments to maximal group competence that prevent the group from combining its resources for optimal task performance, arise from two kinds of deficits, those of motivation and coordination. Group members' motivation to perform is influenced by group size and systems of allocating among group members the rewards for performance. Coordination deficits are seen to occur in association with greater group size and dissimilarity of dispositional qualities among group members.

Steiner's model stimulated a great deal of subsequent research, especially on the relationship of group size to performance for various types of tasks and on differences between individual and group performance on various tasks. The model is often cited as a useful conceptual framework for organizational research on group performance. The task typology, however, has found little use in the description of jobs. Steiner's model raises issues of great concern to organizations, though, such as the impact of staffing and reward practices on group performance.

Shiflett (1979) proposed a representational framework for depicting the determinants of group productivity that subsumes Steiner's and related models. This generalized mathematical formulation depicts group productivity as a function of resources in the group and the constraints operating in a situation that hinder the transformation of group resources into productive output. These constraints include motivation and coordination deficits as well as a host of other factors that affect how resources are utilized. In organizations, these other factors might concern such things as leadership style.

Hackman's Work. Hackman (1982) provided a different perspective on group effectiveness in organizations. This model reveals an evolution in theory development, especially from the model of group performance stated by Hackman and Morris (1975) to that by Hackman and Oldham (1980) to the more recent version. Several features survived over time, and the most recent statement of the model is the most complex.

A starting point in Hackman's model of group effectiveness is the organizational context in which groups perform. Critical aspects of the context are how groups are rewarded, the extent to which the organization provides education and training bearing on group performance, and the extent to which the organization makes available to the group performance-related information, such as feedback and organizational standards. A second category of variables affecting performance pertains to what Hackman calls the design of the group. Issues of concern here are group norms as they pertain to task performance, composition of the group, and the nature of the group task. The nature of the group task is depicted by Hackman in terms quite different from those of Steiner (1972), McGrath (1984), and others. Hackman's concern is not only with the formal requirements of the task but also with how task characteristics motivate group members. Motivating task characteristics include the amount of autonomy inherent in a task and the task's meaningfulness. A third category of variables determining group performance in Hackman's model concerns the availability of assistance and interventions that can be implemented to aid a group at work. In organizations, managers or consultants can be sources of such help.

An interesting distinction is made by Hackman between intermediate indicators and ultimate indicators of group effectiveness. Ultimate effectiveness is defined by group outputs, member satisfaction, and healthy social interaction. Intermediate effectiveness pertains to the quality of the group interaction process as it performs the task at hand. Indicators of the effectiveness of group interaction process in Hackman's model include assessments of the level of member effort, the extent to which resources are applied toward task accomplishment, and the appropriateness of the strategies used by a group to accomplish its task.

The distinction between intermediate and ultimate effectiveness is useful. It suggests that the connection between effective process and outcomes is less than certain for groups. Nowhere is this more apparent than in organizational decision making. Groups can blunder about as they consider few alternatives and misread data yet make a choice that, when implemented, proves to be a beneficial one. Likewise, groups with a careful, meticulous decision process can adopt alternatives that prove inferior. Janis and Mann (1977) discuss this often tenuous link between decision process and outcome. Hackman's model also recognizes that the link between intermediate (or process) and ultimate effectiveness for task-performing groups in general is influenced by a variety of environmental factors, such as technological constraints.

Socio-Technical Work. The socio-technical framework (Cummings, 1978; Trist, 1981) offers another perspective on work group effectiveness in organizational settings. According to this framework, effectiveness is the joint optimization of task and social ends in the workplace. That is, effective groups are those that fulfill not only the task requirements imposed on them by the organization but also the social needs and goals of group members.

From the socio-technical perspective, effectiveness is achieved through the creation of self-regulating work groups (Cummings, 1978). The conditions for creating such groups involve task differentiation, boundary control, and task control. Task differentiation refers to the extent to which the group's task is a complete, meaningful whole and is distinct from the tasks of other groups. Boundary control refers to the degree to which group members exert influence over the physical space in which the group works and its membership, as well as the degree of its independence from outsiders. Groups with strong control over their social and spatial boundaries can thus determine autonomously who belongs, who influences, where the group resides, and other matters of importance. Task control refers to a group's capability to determine its own work methods and goals. Socio-technical theory does not emphasize the demands of a task on group process as determinants of performance (as does Steiner's model, for example). Rather, it stresses that groups determine the processes engaged in to complete the task. When both boundary and task control are high and task differentiation exists, groups are said to be self-regulating and, hence, likely to jointly optimize social and task objectives.

Self-regulating work groups pose a set of conditions not customarily found in organizations, although certain similarities between quality circles and self-regulating work groups can be observed. For example, quality circles are given some degree of task and boundary control. Further, the tasks of quality circle members may often be at least moderately differentiated from the tasks of others. Socio-technical principles constitute a significant departure from usual organizational practices regarding the management of group performance, and evidence exists that their application can lead to effective task performance (Trist, 1981).

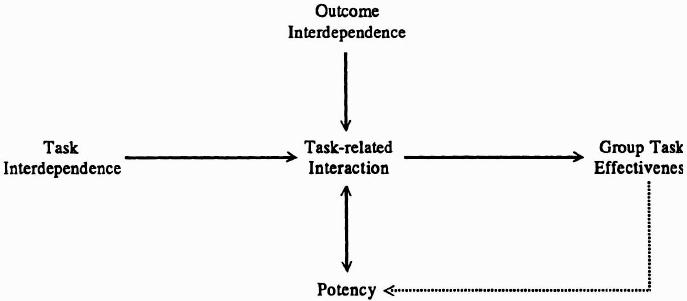

A New Approach. Shea and Guzzo (1984) have developed a theoretical model of work group effectiveness that differs from earlier models. Their model, shown in Figure 2-1, cites three variables as primary causes of work group effectiveness: task interdependence, outcome interdependence, and potency. These variables are said to influence effectiveness through their impact on the task-related interaction of a work group. Effectiveness is defined in terms of accomplishment of that which it is chartered to do.

Figure 2-1. A Model of Group Task Effectiveness.

Source: Shea and Guzzo, 1984.

Task interdependence refers to the degree of task-required cooperation in a group. When task interdependence is low, group members can carry out their roles relatively independently of other members. When task interdependence is high, however, group members must closely coordinate their actions and share resources for attaining task completion. Thus, group tasks differ in their demands for coordinated action among group members. Too little or too much orchestration of action among group members can bring about ineffectiveness. Task interdependence also influences effectiveness by moderating the impact of outcome interdependence.

Outcome interdependence refers to the degree to which important rewards are contingent on group performance. The more valuable rewards (for example, pay) are made available on the basis of group accomplishments, the greater the degree of outcome interdependence among group members. The model assumes that some minimal amount of outcome interdependence is necessary for groups to sustain effective performance.

Not only is the degree of outcome interdependence important to the model but also important is the way in which outcomes are distributed to group members. Based on the work of Miller and Hamblin (1963), Johnson and others (1981), Rosenbaum (1980), and others, it is predicted that effectiveness is hindered when, if task interdependence is high, outcomes earned by a group are distributed in a competitive way to group members. Noncompetitively distributed outcomes in conditions of high task interdependence, however, are predicted to facilitate effectiveness. Competitively distributed rewards may impede the cooperation vital to task accomplishment when task interdependence is high. When task interdependence is low, outcomes distributed either competitively or cooperatively can be expected to enhance effectiveness.

The third major explanatory variable, potency, is motivational in nature. Potency refers to the collective belief in a group that it can be effective. It is similar to Bandura's (1982) concept of self-efficacy, but potency refers to a collective phenomenon. The theory holds that a minimal amount of potency must characterize a group before it can perform tasks effectively, and the greater the potency the greater the effectiveness of a group. It is possible to speculate, however, that too strong a belief in group effectiveness may be detrimental. Janis (1982) reports cases of poor decision-making performance by groups that held unduly favorable self-regard.

Potency is determined by a number of factors. These include perceptions by members of the level of skill and knowledge within the group, the support given the group by leaders and others in an organization, and the availability of resources (tools, information, time) needed to complete a task. As the model in Figure 2-1 shows, a major determinant is performance feedback: Knowledge of past effectiveness is an influential force in shaping beliefs about future effectiveness. The development of the concept of potency owes much to Sayles's (1958) study of the behavior of work groups in organizations. He found different types of groups to exist, differentiated by how powerful each saw itself in solving problems and producing changes in the organization. In the terms of the model in Figure 2-1, some types of groups in Sayles's study experienced greater potency than others.

According to the model in Figure 2-1, task interdependence, outcome interdependence, and potency combine to shape the task-related interaction in groups. As used in that figure, task interaction process refers specifically to those behaviors and exchanges among group members that, directly or indirectly, affect task accomplishment. A great deal of interaction takes place among members of any task-performing group, some of which is relevant to doing a task and some not. Behavior in a group that affects things other than task accomplishment (such as friendship among members) is not incorporated into the model.

On the Meaning of Effectiveness. The ultimate interest of each of the above models is the effectiveness of groups performing tasks. The models based on Hackman's (1982) work and socio-technical theory (Trist, 1981) provide two similar definitions of effectiveness. According to each model, effectiveness is indicated not only by the adequacy of group outputs but also by the extent to which members experience satisfying interpersonal relations. By comparison, Steiner's (1972) account of effectiveness (productivity, in his terms) is content-free. Steiner's model is concerned with groups doing as well as they are able, but the model does not identify any criteria with which to judge whether a group is maximally effective. The model of Shea and Guzzo (1984) is similar to Steiner's in that it does not identify specific attributes of effectiveness. However, Shea and Guzzo assert that effectiveness must be defined situationally in terms of the extent to which a group fulfills its charter. If a group is established to make a decision, then effectiveness for that group would be gauged in terms of the merits of the decision produced by the group; if a quality circle exists to raise the quality of production, its effectiveness would be gauged in terms of the gains in quality it yields. Note, though, that if a quality circle is established to raise production quality and to provide members with satisfying interpersonal relations, then effectiveness for that group would be assessed in terms of both aspects of its charter, according to this model.

Recent research on the link between group interaction process and task effectiveness raises essential questions about the meaning and causes of task effectiveness in groups. Gladstein (1984), for example, reports data that, although group members perceived “good” interaction to be related to high task performance, an objective measure of group effectiveness (sales) in an organization was in fact unrelated to the reported nature of the interaction among group members. Guzzo and others (forthcoming) report data that effective groups, in terms of task accomplishment, are perceived to be characterized by favorable interaction among members and groups with poorer task accomplishment are seen as characterized by poorer interaction process. Similar data were reported by Staw (1975). Further, Guzzo and others (forthcoming) found that groups with favorable interaction process had their task accomplishment evaluated more positively than groups with less favorable interaction process, even though there was no objective difference in the task accomplishment of groups.

These findings indicate that people hold an implicit belief about groups that task accomplishment and quality of social interaction are related (Gladstein, 1984; Guzzo and others, forthcoming; Staw, 1975). Consequently, groups effective in terms of task accomplishment are often groundlessly perceived as having desirable interaction process characteristics and groups with desirable interaction are often erroneously perceived to be effective in task accomplishment. Researchers who define group effectiveness (in part) in terms of favorable social interaction may themselves be expressing this same implicit belief. Task accomplishment and satisfactory social interaction may be separate and independent. If so, perhaps they should not be mixed together as ingredients of effectiveness.

Determinants of Effective Group Decision Making

What can be learned from these general models of group performance that relates to group decision-making effectiveness? What do they say about organizational conditions and properties of groups that facilitate effective decision making in groups? Based on these models, I suggest the following five points are essential considerations.

The Task. The properties of the task confronting a group play an important role in determining group effectiveness, a point recognized by all the models reviewed. The task is important in at least two respects. First, the nature of the task has clear implications for the appropriateness of various performance strategies adopted by groups at work. A performance strategy is a set of norms and procedures operating in a group to guide task accomplishment. Depending on the task, certain performance strategies are likely to be more effective than others. Steiner's (1972) discussion of group productivity recognized this point explicitly, although the concern there was not with differences among decision tasks per se but rather with differences among all tasks that groups perform. The discussion of task interdependence also concerned the fit between demands of cooperation imposed by the task and actual cooperation among group members as a determinant of group effectiveness. Socio-technical theory suggests that effectiveness is enhanced to the degree that a group has a task that is differentiated from the tasks of other groups.

In regard to decision-making groups, greater attention needs to be given to differences among the various decision tasks encountered and the implications of those differences for the use of various strategies for making decisions in groups. Performance strategies for group decision making are examined more thoroughly below.

A second reason why the task is an important consideration in group decision-making effectiveness is its motivational properties. High motivation means high effort. Hackman's work (Hackman and Oldham, 1980; Hackman, 1982) strongly suggests that group member motivation is affected by factors such as the importance of the group task and the extent to which groups engage in whole tasks. Socio-technical theory, too, emphasizes the importance of meaningful, whole tasks to group effectiveness.

For decision-making groups, then, the implication is that motivation will be high when important issues are addressed and when decision-making groups are engaged in all four phases of decision making: intelligence, design, choice, and review. A common practice in organizations is for groups to become involved in decision making only in the choice phase, such as when a meeting of managers is called to approve one of several alternative courses of action brought to them by subordinates. In this case the decision-making task is fractionated—those engaged in intelligence and design are not those who engage in choice. Breaking up in this way the work of decision making may affect motivation. The nature of organizations and information is such that it is impossible (and undesirable) always to have a single group of people complete a whole decision-making task from intelligence to review, but it is useful to think about exploiting opportunities for groups to complete whole decision-making tasks because of the apparent motivational benefits of doing so.

One caveat about the motivational properties of important, whole decision-making tasks is based on work by Janis (1982; Janis and Mann, 1977). Janis suggests that important decisions, those with substantial consequences, can be stressful, and that this stress may lead decision-making groups to make poor decisions if they cope with the stress inadequately. It may be, then, that an optimal level of motivation exists for decision tasks, and that optimal level is generated either by the task itself or by techniques for managing motivation when it is below or above that optimum.

Rewards. It is hardly surprising that rewards are important determinants of group effectiveness. Of concern here are rewards attainable by the group on the basis of the group's task completion and goal attainment. In the models reviewed, the importance of rewards to group performance is recognized by the work of Hackman (1982), Steiner (1972), and Shea and Guzzo (1984).

Rewards for group achievements can affect both the effort and coordination of a group. Effort, of course, is affected through the incentive value of the rewards. Rewards that an organization can provide groups include pay, recognition, and time off. Coordination, on the other hand, is affected by the way rewards earned by the group are distributed. As discussed earlier, distributions that induce competition among group members (for example, the “best” individual receives the entire reward) may be dysfunctional when tasks demand a high level of coordination. As is true for other tasks, the proper administration of rewards for group performance can be expected to facilitate effectiveness in decision making.

Unfortunately, rewards for group performance generally are not very common in organizations. For example, incentive pay plans that reward group performance are used very infrequently in comparison to those that reward individual or organization-wide performance (Nash and Carroll, 1975). The establishment of quality circles, though, has brought attention to the need to build into organizations ways of rewarding group performance (Munchus, 1983; Thompson, 1982). Some organizations, especially Japanese firms, reward quality circles with money and recognition (Cole, 1979; Munchus, 1983; Thompson, 1982). These rewards are, in part, based on excellence in the decisions made and implemented by quality circles. It may be problematic, however, to reward decision-making groups other than quality circles for their performance (Murnighan, 1982). Decision-making groups such as committees and task forces often form and disband in relatively short periods of time, and other decision-making groups may be made up of people from various quarters of the organization who meet informally only for the time necessary to make a particular decision. Thus, it may be that rewarding such intact, long-term groups as quality circles for their decision-making performance is more easily accomplished than rewarding the many other kinds of groups engaged in decision making in organizations.

Resources. It is indisputable that effectiveness depends on the resources embedded in the composition of a group. Insufficient skill, expertise, or strength for a task doom a group to failure. And as pointed out by Shiflett (1979) and others, the mere presence of the right resources does not guarantee effectiveness. Effectiveness also depends on the manner in which those resources are converted into group products through the group's interaction.

Apart from membership resources, resources in the organizational environment also appear to be an important determinant of group effectiveness. Groups that are able to tap an organizational environment rich in resources are more likely to be effective than those that are unable to do so. In Hackman's model of effectiveness, resources that an organization can provide include training and development for group members, advice, and planned interventions (for example, team-building experiences) that can change the group in the interest of greater effectiveness. Organizational resources also play a role in affecting a group's sense of potency, according to Shea and Guzzo (1984). Potency refers to the collective belief by a group that it can be effective, and an important influence on that belief is the extent to which the organization makes available to a group the support the group needs to accomplish its work. Teams in retail stores, for example, will need on different occasions display racks, accounting forms, adequate floor space, training in product knowledge, and other goods or support services that relate to the task of selling. Thus, the availability of resources from the environment in which groups perform tasks is a determinant of effectiveness.

The performance of decision-making groups can be aided through the existence of decision support systems in organizations. Decision support systems may involve computerized information processing that helps groups manage the data on which decisions are based, such as by aggregating and displaying information in new ways and easing the difficulties of estimating consequences of proposed alternatives. Computers also can help resolve conflict in decision-making groups (Cook and Hammond, 1982), as discussed more thoroughly below. Computers as resources hold great potential for enhancing the effectiveness of decision-making groups, although few demonstrations of their favorable impact on organizational decision making exist (Bass, 1983).

Autonomy. Two theoretical perspectives on group effectiveness emphasize autonomy as an essential ingredient in successful group performance. Hackman's (1982) model regards autonomy as a necessary element in the design of the group and its task because autonomy is viewed as stimulating effort, the use of member skills and abilities, and the adoption of an appropriate task performance strategy. The socio-technical perspective regards autonomy as crucial to the creation of truly effective work groups because autonomy enables the group to control its own task performance procedures and boundary transactions.

Investing autonomy in a decision-making group empowers it in a number of ways. With autonomy, groups can determine their membership, rules for meetings, division of labor, rules for selecting one alternative over another, and methods of reviewing past choices. Returning to the example of quality circles as decision-making groups, it can be seen that these groups experience considerable autonomy in selecting the problems they address. Autonomy in a decision-making group, however, does not always coincide with responsibility for decisions. A work group may have autonomy in specifying problems and devising solutions, but a decision may require approval from a different level in the organization before it can be implemented. Thus, responsibility for implementing the chosen course of action resides outside that group.

Appropriate Performance Strategies. A fifth stimulus to group decision-making effectiveness that can be derived from the general models reviewed is the importance of the appropriateness of the group's performance strategy for fulfilling the demands of its task. The general models of both Steiner (1972) and Hackman (1982) state that, for groups to be effective, they must adopt performance strategies that are consistent with the performance requirements of the task. With regard to decision-making groups, there is little systematic analysis of the fit between available performance strategies and the demands of decision making, which I will explore in the next section.

Performance Strategies for Group Decision Making

Various performance strategies available to groups are discussed here as those strategies pertain to the distinct demands of the four phases of decision making.

Intelligence Phase. The intelligence of decision making is concerned with identifying circumstances calling for a decision. Those circumstances include crises, the resolution of problems, and opportunities for new and innovative actions. Intelligence (and review) activities are not nearly as well understood as design and choice activities (Edwards, 1954), and thus it is difficult to specify appropriate norms and procedures for decision-making groups to adopt when performing intelligence activities. Some possibilities, though, are described below.

Strategies for identifying problems in need of resolution through decision making adhere to a basic principle of detecting a discrepancy between what is and what should be (Bass, 1983; Taylor, 1984). What should be is a standard or goal against which to evaluate a present state of affairs, and a description of what should be is predicated on agreement about goals and goal clarity. Often in organizations goal agreement and clarity exist, but sometimes they do not, leading to differences of opinion about whether or not decisions need to be made.

When objectives are clear, deviations from them can be assessed through systematic analysis of the source and magnitude of the discrepancy. Kepner and Tregoe's (1965) approach to discovering problems relies on the use of a series of structured questions pertaining to the nature of and reasons for a discrepancy from goals. A similar technique for organizing information about a problem is force field analysis (Ulschak, Nathanson, and Gillan, 1981). When applied to groups, it first requires them to define as precisely as possible the discrepancy between present and desired conditions. Next, force field analysis calls for specification of the “driving” and “restraining” forces as they pertain to achieving desired conditions. Driving forces are those things that help bring about the desired end; restraining forces are those that prevent it. To illustrate, assume a decision-making group is formed to determine how to reduce turnover among part-time employees in an organization. The desired state is, say, 5 percent turnover per month while the present state is 15 percent monthly turnover. Forces that prevent the desired state might include low wages, poor working hours, and a mismatch between work force skills and job demands. Forces that help achieve the desired state might include a favorable organizational climate, skillful management, and a work force dominated by students and others who typically seek part-time employment. After identification of driving and restraining forces, force field analysis calls for the assessment of their relative strengths. Which forces are the most powerful in preventing the desired state? Which are most powerful in helping to achieve the desired state? Following this step, the group can move on to the design phase of decision making to create alternative courses of action that would solve the problem without weakening the favorable driving forces while eliminating the most powerful restraining forces acting to prevent attainment of the desired state.

Force field analysis is simply a way of organizing information in a group that helps to identify problems calling for a decision. It is neither jazzy nor technologically advanced, yet it does provide a performance strategy for groups to adopt in the intelligence phase of decision making.

A different strategy for use by groups in intelligence activities is brainstorming. Brainstorming is, as mentioned earlier, a technique often used in quality circles to generate alternative courses of action. It is a technique that also can be used in the intelligence phase of decision making to identify problems and opportunities for decision making.

Brainstorming is a strategy that relies on four essential rules to govern a group meeting (Stein, 1975). The rules are (1) criticism is ruled out, (2) freewheeling is welcomed (that is, any idea is acceptable to report), (3) as many ideas as possible should be stated, and (4) combining and improving already stated ideas is desired. The concern of brainstorming is the generation of ideas in a nonevaluative atmosphere. It is predicated on assumptions that the best ideas appear when they are not subject to immediate evaluation and when dominant, relatively common ideas have already been released (hence the emphasis on quantity and combination).

Considerable controversy exists in the research literature regarding the merits of brainstorming as a performance strategy for groups, in part because some studies compared the performance of brainstorming groups to nonbrainstorming groups while other studies compared the performance of brainstorming groups to that of individuals. When compared to individuals, brainstorming groups are not superior; when compared to other groups, however, brainstorming groups appear superior (McGrath, 1984). Thus, brainstorming appears to have value as a strategy for managing the intelligence and design activities of groups.

Design Phase. A number of performance strategies exist for use in the design phase of decision making. Brainstorming, just described, is one technique applicable when alternative courses of action must be devised. Other techniques for generating novel ideas are described by Stein (1975) and Maier (1970). A technique that has enjoyed a measure of popularity in organizations is the nominal group technique (NGT) (Delbecq, Van de Ven, and Gustafson, 1975).

NGT imposes a sequence of steps that control the interaction among group members during decision making. The steps of NGT actually extend into the choice phase of decision making. The first step calls for group members to work silently in generating their own lists of alternative solutions. The second step then requires group members to report in round-robin fashion the alternatives each generated during the prior step. These are recorded publicly on a master list, and the members are given sufficient opportunity to exhaust their private lists of alternatives. Discussion among members during this stage is not permitted; talking is permissible only to report an alternative from one's list. The third step permits discussion but restricts it to issues of clarification and brief comment on the alternatives on the master list. The objective of this stage is to ensure that all group members understand each alternative and to provide each alternative limited exposure to evaluative comments. At the conclusion of this step in the NGT, the last step is one of selecting a single alternative through voting.

NGT imposes structure and limits discussion in the interest of effective decision making. The procedure, in effect, attempts to reduce process losses due to social interaction and lack of task orientation in groups. Evidence of favorable effects of NGT exists (for example, Delbecq, Van de Ven, and Gustafson, 1975), although that evidence is best construed as showing that groups using NGT tend to produce greater numbers of alternative solutions than groups not using NGT, but the quality of alternatives generated by NGT is not necessarily greater than the quality of alternatives generated by groups not using NGT (Guzzo, forthcoming).

The application of computers, in the manner described by Cook and Hammond (1982), to aid decision process in groups provides a unique performance strategy for facilitating design activities. Cook and Hammond argue that a common obstacle to effective group decision making is conflict, especially in the expression of divergent points of view by group members. They suggest, in fact, that people are relatively poor communicators of their own thinking on a decision issue and that much ineffectual verbal debating ensues in groups because of this. To overcome this problem, Cook and Hammond describe a way of representing, through computer-based mathematics and graphics, each group member's “judgment policy.”

A judgment policy refers to the manner in which an individual weighs the importance of different factors in a decision and combines those factors into a preference for one alternative over others. Since individuals are relatively ineffective at communicating judgment policies, a method of depicting differences among group members' judgment policies and communicating these differences may aid groups greatly. The method advocated by Cook and Hammond is multiple regression analysis of the relationship between preferences for alternatives and points of information relevant to the evaluation of alternatives. Applied to each group member, such analysis yields a statistical model of how each person weighs the importance of each pertinent factor for each alternative. For example, differences of opinion may reside in a group given responsibility for deciding what computer network system an organization should purchase. The opinion differences may concern many possible factors relevant to the purchase, such as cost, ease of implementation, service, expandability of the system, and so on. Policy capturing through multiple regression can provide the group with a picture, in objective terms, of exactly how group members disagree with regard to the importance each member gives to the various factors and, thus, why group members disagree about which alternative computer system to purchase.

The general applicability of the policy-capturing method described by Cook and Hammond is limited because of requirements of time to put it in place and accessibility to computers, but once established the method can be used repeatedly with relative ease. More details of the method are described by Cook and Hammond (1982). Of interest here is the usefulness of adopting the policy-capturing strategy to give members insights that might otherwise be unattainable. These insights can lead to the creation of other alternatives that satisfy all members' concerns for the factors to be considered in making a choice. Thus, policy capturing is a diagnostic device. It does not prescribe a way of choosing among alternatives but it does give a unique view for group members to think about existing alternatives and can lead to the development of new alternatives.

Choice. The process of choice, selecting one from among two or more alternatives, has been studied in a variety of ways. Many studies of choice in groups are descriptive. That is, they seek to describe how it is that groups arrive at a commitment to one alternative. Some but not all such descriptive studies lead to prescriptions for managing group interaction during the choice phase to enhance effectiveness. Other prescriptions for appropriate performance strategy during choice arise from research on individual decision making.

One line of research describing how groups make choices grew out of Davis's (1973) social decision schemes framework. This framework seeks to identify by what rule individual preferences become translated into group choices. Possible rules include unanimity (all individuals must agree) and majority rule. Most groups appear to operate on the basis of majority rule to make choices, although the strength of the majority required for choice and other aspects of choice processes have been found to vary according to group size, power differences among members, and other situational factors (McGrath, 1984; Murnighan, 1982).

A different descriptive approach is Hoffman's (1979, 1982) work on the relationship between the valence of alternatives and the selection among them by groups. According to Hoffman's model, valence is a force toward the adoption of an alternative. Each alternative acquires valence during group discussion. The strength of an alternative's positive valence is determined by the number of favorable and unfavorable comments made about it, and the likelihood of its adoption is directly related to the strength of its positive valence. Hoffman (1982) suggests that the accumulation of valence by an alternative is an implicit process, one that goes on out of the awareness of group members, and that the valence accumulated by alternatives is often unrelated to the quality of alternatives. Thus, the favored alternative in a group is not always the best. Hoffman (1982) discusses a number of implications of his model for improving the decision process of groups by preventing an alternative from being adopted too early or without adequate justification.

Techniques for making choices abound in the literature (Bass, 1983; Taylor, 1984), although these techniques are not necessarily targeted for use with groups and little evidence exists of their impact on group decision-making effectiveness. Examples of these techniques include the use of a decision matrix and multiattribute decision analysis. A decision matrix is a means of systematically arraying the alternatives under consideration and the attributes, positive and negative, of the alternatives. The matrix facilitates comparisons among alternatives and, thus, should facilitate the choice process. Multiattribute utility analysis is, in a sense, a refinement and extension of the use of a decision matrix. It calls for a display of alternatives and their attributes, but it also calls for each attribute to be assigned a value (for example, purchase cost) and a weight of importance. The values of each attribute are standardized, and the standardized values are then multiplied by the weight assigned to each attribute. Since each alternative course of action has multiple attributes, the means of arriving at a choice are to add the “scores” (that is, the products of the attribute weight times attribute value) for each alternative and to adopt the alternative with the most favorable score. Note that multiattribute utility analysis, however, says little about how to arrive at agreement among group members when they differ in their assessments of weights and values for attributes.

While no single best technique for choice has been identified for use with groups, a technique for challenging favored alternatives has been found useful in decision-making groups. That technique is performing the role of “devil's advocate.” In the devil's advocate role a group member challenges the merits of an alternative favored by the majority of the group, airing arguments against the alternative and testing the wisdom of selecting it. The objective of the role, of course, is to prevent poor choices resulting from hurried or careless considerations. Evidence of the usefulness of the role in government decision-making groups is reported by Janis (1982) and George (1975). The usefulness of the role may depend heavily on the style with which it is carried out. Schwenk and Cosier (1980) found that a devil's advocate as a carping critic added little to decision-making effectiveness but an objective, nonemotional devil's advocate enhanced effectiveness.

Review. Owing to a dearth of research in this area, there are few performance strategies to be considered for use by groups during the review phase of decision making. However, there are interesting findings regarding postchoice experiences of individual decision makers that appear relevant to decision-making groups. These findings concern postchoice rationalization and escalating commitment to a choice.

Research on postchoice rationalization suggests that considerable energy is spent by individuals to justify a choice just made (Bass, 1983; Janis and Mann, 1977). This postchoice rationalization can be useful in that it can build commitment to the chosen alternative that may sustain efforts to implement it. On the other hand, justifying the choice can diminish the capacity to evaluate objectively the merits of its implementation. Thus, the need for a new decision making may be missed. Relatedly, research on escalating commitment shows that individuals tend to adhere too long to a chosen course of action in the face of mounting costs (Staw, 1976). In other words, once a line of action gets under way consistent with an initial choice, individual decision makers find it difficult to break away from it.

The extent to which the review activities of decision-making groups are subject to the influences of postchoice rationalization and escalating commitment to action is not clear at this time. Awareness of such phenomena, however, may prove useful to groups examining the consequences of choices they made.

Summary

Decision making is comprised of four types of activity: intelligence, design, choice, and review. These activities can be considered phases in a cycle, although the phases do not necessarily occur in a strict, orderly progression and each phase shares elements of the activities of the other phases. This definition of decision making subsumes a number of distinctions among group tasks made by other group researchers and adds a significant measure of complexity to the study of group decision making. Such a definition, however, provides a realistic account of the activities of decision-making groups in organizations and forces the consideration of multiple factors as determinants of decision-making effectiveness.

General theoretical frameworks of group performance give insight into determinants of effective decision making by groups in organizations. These determinants include (1) the nature of the decision task, both in terms of the demands it places on the group interaction process and its motivational properties, (2) the existence of rewards for task performance by groups and the distribution of those rewards in a way that facilitates the member interaction and effort needed to perform a task, (3) the availability to the group of those resources, found both within the group and in the group's environment, that facilitate task performance, (4) autonomy for groups in their work as decision-making units, and (5) the appropriateness of performance strategies for groups to implement when making decisions. Potential performance strategies for use by decision-making groups were reviewed for their relation to the four phases of decision making. In terms of managing groups for effective decision making, organizations can act to ensure effectiveness by managing the conditions in which groups make decisions and the procedures used to make them.

A Look Ahead

In this section I wish to suggest some directions for future research and theorizing that I believe will lead to significant advances for understanding and practice. The list of points below pertains to the study of decision-making groups in organizations and follows closely from many of the issues already discussed. By no means is the list exhaustive.

1. Focus on all phases of decision making. Past research and theory on group decision making has focused almost exclusively on the design and choice phases of decision making. As mentioned previously, the focus of past research is strongly tied to the predominance of a certain method of research. The neglected phases of decision making, intelligence and review, need to receive more research attention, and theories of group decision making that span the four phases stand to make substantial contributions. It was noted that much recent research on group decision making is descriptive in nature, aimed at uncovering the processes that go on “naturally” in decision-making groups. It may be worthwhile to develop normative theories of group decision making—that is, theories of how it should occur throughout its four phases—and then conduct research to test these theories. Much of Maier's (1970) early work on group decision making and creativity was normative in nature and generated many useful prescriptions for enhancing effectiveness.

2. Field experiments are needed. Although there is an appreciable body of literature on group decision making, relatively few research reports exist of experimentation with group decision making in field settings. Most experimental research to date has been with groups in laboratory settings, and most field research has been nonexperimental. Thus, a need for field experiments exists, especially with regard to the impact of various performance strategies on group decision-making effectiveness. Does the nominal group technique “work” when used repeatedly by decision-making groups in organizational settings? What are the conditions that make the devil's advocate role most successful in aiding decision-making quality (see George, 1975)? How do changes in group membership affect the performance of a decision-making group? These and many other questions are answerable through controlled experimentation in field settings.

3. Examine differences in decision tasks. The intelligence phase can reveal many different kinds of occasions for decision making, and it will be fruitful to examine more closely the kinds of decision tasks addressed by groups. A gross but useful distinction of this sort already discussed was that of crises, problems, and opportunities made by Mintzberg, Raisinghani, and Theoret (1976). A more detailed analysis may find, for example, that within each of these categories there are identifiable differences among decision tasks that have implications for the appropriateness of various performance strategies. Decision tasks surely differ in the demands they place on each of the four phases of decision making, and the development of theory relating the demands of decision tasks to performance strategies for groups may prove very valuable.

4. Consider the role of motivation in decision making. General thories of group performance frequently cite the importance of motivation in determining performance, such as by citing the role of member effort or the effects of incentives in a group. Theories related to group decision making, however, seem not to focus on motivational factors. Instead, the focus tends to be on information processing or social interaction. If motivation is an important determinant of group performance in general, then it should also be so for group decision-making performance: Motivation may play a significant role in driving information search behaviors, creativity, and other components of group decision making. Many factors conceivably could influence motivation in decision-making groups, including incentives, the importance of the decision task, or the degree of involvement in all phases of decision making, and there is ample opportunity to explore the causes and consequences of motivation in decision-making groups.

5. Access resource needs. Effective decision making by groups in organizations may often require many resources, and the resource needs of groups may change as groups pass through the various stages of decision making. Research on group performance traditionally has given much attention to how groups make use of the resources within a group (especially as those resources reside in group members in the form of expertise) but comparatively little attention to understanding how groups make use of resources outside the group, such as resources provided by the organizations in which groups work. The transactions between a group and its environment, especially those through which a group draws from its environment the information, guidance, tools and other resources that aid group performance, should prove to be a worthwhile topic of investigation in the study of group decision making. The nature of those transactions may well vary with the phases of decision making.

6. Prepare for the future. There is a computer revolution going on, even if it is less sudden or sweeping than many prognosticators thought. The use of computers has many implications for group decision making, especially related to ways of processing information and interacting with fellow group members. Computer conferencing, for example, is a method by which a group can engage in decision making without meeting face-to-face. The impact of such technology on group decision making is an important area of research and theorizing (Kiesler, Siegel, and McGuire, 1984). Future research on this topic might want to consider not only what technology does to groups as decision makers but also examine how that technology can best be managed for raising the effectiveness of decision-making groups.

References

Alexander, E. R. “The Design of Alternatives in Organizational Contexts: A Pilot Study.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 1979, 24, 382–404.

Bandura, A. “Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency.” American Psychologist, 1982, 37, 122–147.

Bass, B. M. Organizational Decision Making. Homewood, I11.: Richard D. Irwin, 1983.

Carter, L. F., Haythorn, W. W., and Howell, M. “A Further Investigation of the Criteria of Leadership.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1950, 46, 589–595.

Cole, R. E. Work, Mobility, and Participation: A Comparative Study of American and Japanese Industry. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

Cook, R. L., and Hammond, K. R. “Interpersonal Learning and Interpersonal Conflict Resolution in Decision-Making Groups.” In R. A. Guzzo (ed.), Improving Group Decision Making in Organizations: Approaches from Theory and Research. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1982.

Cummings, T. “Self-Regulating Work Groups: A Socio-Technical Synthesis.” Academy of Management Review, 1978, 3, 625–634.

Davis, J. H. “Group Decision and Social Interaction: A Theory of Social Decision Schemes.” Psychological Review, 1973, 80, 97–125.

Delbecq, A. L., Van de Ven, A. H., and Gustafson, D. H. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes. Glenview, I11.: Scott, Foresman, 1975.

Einhorn, H. J., and Hogarth, R. M. “Behavioral Decision Theory: Processes of Judgment and Choice.” In M. R. Rosenzweig and L. W. Porter (eds.), Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 32. Palo Alto, Calif.: Annual Reviews, 1981.

Edwards, W. “The Theory of Decision Making.” Psychological Bulletin, 1954, 51, 380–417.

Foushee, H. C. “Dyads and Triads at 35,000 Feet: Factors Affecting Group Process and Aircrew Performance.” American Psychologist, 1984, 39, 885–893.

George, A. L. “Appendix D: The Use of Information.” In Commission on the Organization of Government for the Conduct of Foreign Policy. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975.

Gladstein, D. L. “Groups in Context: A Model of Task Group Effectiveness.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 1984, 29, 499–517.

Guzzo, R. A. Managing Group Decision Making in Organizations. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, forthcoming.

Guzzo, R. A., and Waters, J. A. “The Expression of Affect and the Performance of Decision Making Groups.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1982, 67, 67–74.

Guzzo, R. A., and others. “Implicit Theories and the Evaluation of Group Process and Performance.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, forthcoming.

Hackman, J. R. “Effects of Task Characteristics on Group Products.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1968, 4, 162–187.

Hackman, J. R. “A Set of Methods for Research on Work Teams.” Technical Report No. 1, School of Organization and Management, Yale University, 1982.

Hackman, J. R., and Morris, C. G. “Group Tasks, Group Interaction Process, and Group Performance Effectiveness: A Review and Proposed Integration.” In L. Berkowitz (ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 8. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1975.

Hackman, J. R., and Oldham, G. Work Redesign. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1980.

Hoffman, L. R. (ed.) The Group Problem Solving Process: Studies of a Valence Model. New York: Praeger, 1979.

Hoffman, L. R. “Improving the Problem-Solving Process in Managerial Groups.” In R. A. Guzzo (ed.), Improving Group Decision Making in Organizations: Approaches from Theory and Research. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1982.

Janis, I. L. Victims of Groupthink. (2nd ed.) Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982.

Janis, I. L., and Mann, L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment. New York: Free Press, 1977.

Johnson, D. W., and others. “Effects of Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic Goal Structures on Achievement: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin, 1981, 89, 47–62.

Kepner, C. H., and Tregoe, B. B. The Rational Manager. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965.

Kiesler, S., Siegel, J., and McGuire, T. W. “Social Psychological Aspects of Computer-Mediated Communication.” American Psychologist, 1984, 39, 1123–1134.

Laughlin, P. R. “Social Combination Processes of Cooperative, Problem-Solving Groups as Verbal Intellective Tasks.” In M. Fishbein (ed.), Progress in Social Psychology. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1980.

McGrath, J. E. Groups: Interaction and Performance. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

Maier, N. R. F. Problem Solving and Creativity: In Individuals and Groups. Monterey, Calif.: Brooks/Cole, 1970.

Miller, L. K., and Hamblin, R. L. “Interdependence, Differential Rewarding, and Productivity.” American Sociological Review, 1963, 28, 768–778.

Mintzberg, H., Raisinghani, D., and Theoret, A. “The Structure of ‘Unstructured’ Decision Processes.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 1976, 21, 246–275.

Munchus, G. “Employer-Employee Based Quality Circles in Japan: Human Resource Policy Implications for American Firms.” Academy of Management Review, 1983, 8, 255–261.

Murnighan, J. K. “Game Theory and the Structure of Decision Making Groups.” In R. A. Guzzo (ed.), Improving Group Decision Making in Organizations: Approaches from Theory and Research. Orlando, Fla. : Academic Press, 1982.

Nash, A. N., and Carroll, S. J. The Management of Compensation. Monterey, Calif.: Brooks/Cole, 1975.

Nutt, P. C. “Models for Decision Making in Organizations and Some Contextual Variables Which Stipulate Optimal Use.” Academy of Management Review, 1976, 1, 84–98.

Rosenbaum, M. E. “Cooperation and Competition.” In P. B. Paulus (ed.), Psychology of Group Influence. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1980.

Sayles, L. R. The Behavior of Industrial Work Groups: Prediction and Control. New York: Wiley, 1958.