9

![]()

Thought Experiments and the Problem of Sparse Data in Small-Group Performance Research

James H. Davis

Norbert L. Kerr

The steady increase in social research during this century is astonishing. For the past three decades the effort has been especially rapid and has led to a very large literature of empirical studies. However, beginning about a decade and a half ago, a strong movement developed to demonstrate the relevance of social research to society's needs. Applied social psychology was not new, but the intensity of interest was different; indeed the particular focus of application continues to change. Along with the “new concern” there arose considerable disappointment about the degree of apparent usefulness of much empirical social research. There seem to have been at least two general kinds of disappointment: (1) Findings were judged to be “unstable.” Often results from research conducted at one place or time was not consistent with data gathered earlier from else-where. (2) Despite the large number of empirical findings there rarely appeared to be a good one-to-one match between available empirical results and an applied question. Such poor matches often resulted in a plea to “do one more study” and sometimes in outright condemnation of the social psychology enterprise as irrelevant.

These two sources of discontent seem to have figured significantly in the rise of the “crisis in social psychology” so important to critics of the day (for example, Gergen, 1973). One general response to the “crisis,” or disappointment with social research, was to advocate collecting more data, especially in the “field” or the “real world.” The real world or the field were generally thought to be places such as organizations and institutions where people typically behaved “naturally.” Among the more important activities of an especially interpersonal character were those associated with deciding criminal guilt, constructing corporate policy, establishing cabinet positions, or selecting new personnel.

This chapter will address the collection of problems we have outlined above, not by suggesting a reduction in our commitment to empirical research but by suggesting that thought experiments supplement such efforts. The thought experiment is an aid to extrapolating from known empirical results and interpolating between existing sets of findings. At the most fundamental level, the thought experiment is simply another name for simulation/modeling. We have chosen the label thought experiment partly as a disguise in order to achieve greater acceptability than heretofore among social researchers and partly to stress the implications of results rather than the mechanics of calculation.

Mathematical models in social psychology have typically been used, as in other fields, for explanation and prediction of empirical phenomena. There has been almost no use of modeling in the fashion we shall suggest here—a sharp contrast to other sciences, ranging from aeronautical engineering to economics. There are probably several reasons for this reluctance to use models in the design of institutions, the evaluation of social change, or the description of organizational systems that are too complex for direct study in a simple way. We suspect at least one of these may be due to a history in which schools of psychology, grand systems for understanding “man,” and armchair psychology for so long played a significant role with minimal guidance from systematically gathered data. From another perspective, the political and religious ideologies of social thought have sometimes been so coherent, comprehensive, and intuitively compelling that data seem superfluous—a problem that has plagued social and behavioral science from earliest times to the present day. Indeed, statements of “show me your data” or “let the data do the talking” have proved valuable tools for refuting ideologically derived assertions about social behavior.

In any event, it now seems useful to consider some kinds of formal theory (whether mathematical or computer models, or something else) for assessing the practical impact of social and institutional changes, and especially proposals for such. In the future we may find that many rich and interesting theories of social behavior, now largely posed in verbal form, may benefit from the quantitative treatment we see routinely in, say, economics. In this connection, it is worthwhile to note that Harris (1976) has advanced the notion that many logical consequences of current theories in social psychology are not intuitively obvious. Moreover, unsuspected contradictions and inconsistencies are sometimes evident upon more formal treatment that allows extended examination.

We will explore below several examples of thought experiments taken from the general area of group performance. Again, our major objective will not be to supplant data by theory but to supplement existing empirical data with plausible theoretical models. Thought experiments, too, require data, if for no other reason than the replacement of assumptions about parameters with good estimates.

Group Decision Making: Jury Verdicts

We first consider extrapolations from a substantial set of data to a fairly specific social institution: the jury. This shift entails restrictions on potential thought experiments as a result of custom and law. A full description of the current role of the jury in contemporary civil and criminal proceedings in the United States is beyond the scope of this discussion. (See Gleisser, 1968, and Van Dyke, 1977, for comprehensive accounts.) However, we might note that the jury is a popular institution. Legislative or judicial actions affecting it stimulate considerable interest among experts and laymen alike. For our purposes, jury research illustrates well the difficulties often associated with obtaining social system information.

There are strict legal restrictions on directly gathering data from juries during actual deliberation. Moreover, trial records are frequently ambiguous, and, in any event, represent a single jury hearing a unique case. Finally, there is no single entity that can be clearly labeled the jury. In addition to the federal court system, the various state court systems may differ and judicial practices vary in subtle but important ways from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. With not one but several “targets,” thought experiments are an especially important supplement to empirical research injury behavior.

In a criminal trial, the jury is assigned the task of determining guilt, whereas in a civil trial it must assign culpability. The former setting occasionally finds the jury subsequently recommending or even setting sentence in a few instances, and the latter usually must award damages or the like. Most of the empirical research effort to date has focused upon criminal trials and the behavior of individual jurors. The obvious difficulty in obtaining sufficient samples of juries has proved to be a serious handicap. Finally, it is important to recognize that most data (for the reasons mentioned earlier) come from mock trial experiments in which subjects are recruited to play the role of jurors (Bray and Kerr, 1982). (See Davis, Bray, and Holt, 1977, and Kerr and Bray, 1982, for comprehensive reviews of empirical and theoretical research on jurors and juries alike.) This discussion will be concerned only with criminal juries and with just three features of juries: jury size, jury composition, and assigned decision rule.

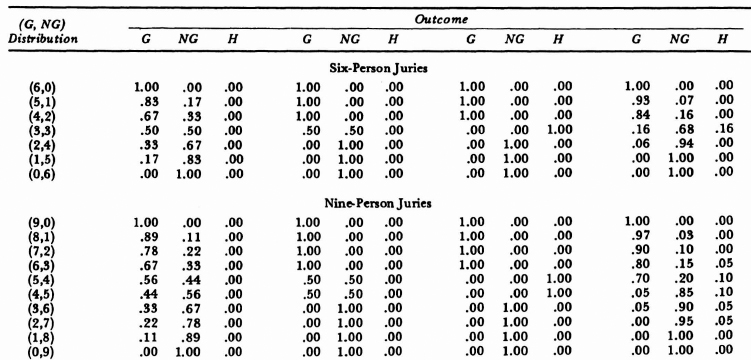

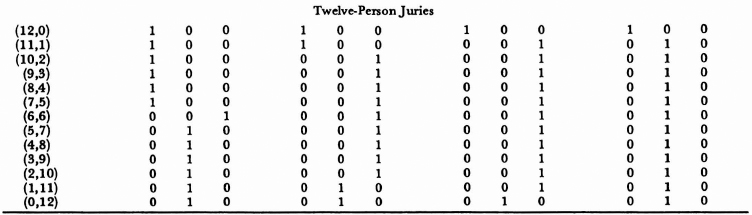

Social Decision Scheme Theory. Historically, criminal juries in the United States have deliberated to a unanimous verdict; whatever the initial array of opinion might have been, the verdict was returned when all members of the jury agreed upon a verdict. Supreme Court decisions in recent years have held that state or federal law permitting juries less than unanimous verdicts are not prohibited by the Constitution (Apodaca and others v. Oregon, 1972; Johnson v. Louisiana, 1972). Indeed, the controversial nature of these decisions led to much of the current interest in group social decision rules. Currently, some social decision rules less than unanimity are permitted, most frequently a two-thirds majority being sufficient to establish a verdict. From the standpoint of the social researcher, we are concerned with any effects from the array of various majorities running from simple to some higher order; an exhaustive evaluation of jury performance would inspect this entire array. Moreover, the social decision rule assigned to a jury may influence but may not completely determine the social combination process that actually provides the best prediction of the final verdict. Consequently, we may think of the social combination rule actually best describing the social deliberation process, whatever the voting mechanics, as a social decision scheme. A social decision scheme is a summary principle describing the interpersonal interaction that acts upon the initial individual member input and yields the final group output—in this case, the verdict. More precisely, for every possible array of opinion at the outset of group deliberation, there is some probability of this interaction yielding a guilty, not guilty, or hung out-come (for the jury that cannot satisfy the decision rule). Some alternative decision schemes for six-, nine-, and twelve-person juries are given in Table 9-1 by way of illustration.

Observe that the distribution of initial preferences of individual jurors (along the rows) is between a guilty and a not guilty verdict, since the undecided juror is obligated to favor not guilty under legal norms. Jury deliberation, however, has three possible outcomes: guilty, not guilty, or hung. Entries in the matrices show outcomes under four different social decision schemes. The first matrix of the top row shows that a two-thirds majority (also a simple majority for the six-person jury) determines a verdict when it exists after the start of deliberation, but for an initial three-three split the predicted outcome is hung. The second matrix in the top row shows a majority of five-sixths determining a verdict; otherwise the outcome is hung. All matrices in the table are read in a similar fashion. Observe that the size of the jury determines what social decision schemes are even possible. Size is especially important in determining the opportunity for ties or preference arrays that do not meet a majority rule. For example, there is no possible tie between jurors inclined to guilty and not guilty in nine-person juries, but the possibility exists for six- or twelve-person juries. Such nuances of size and rule interaction can play an important, though often quite subtle, procedural role in determining outcomes.

Table 9-1. Matrices of Social Decision Rule Possibilities for Criminal Juries.

Note: G = guilty, NG = not guilty, H = hung jury.

Next, we entertain the notion that, given a particular distribution of opinion at the outset, there may be only some probability that a guilty, not guilty, or hung verdict will follow. The confluence of numerous personal and social interaction variables moderates a certain determination of outcome by relative numbers of advocates. Thus, conditional probabilities, [dij], replace the binary entries in the social decision scheme matrices. Examples for juries of six, nine, and twelve are given in Table 9-2.

The m × n social decision scheme matrices, D, of Table 9-2 summarize the many complexities of social interaction, whereby the ith of the m possible initial distributions of member opinion will ultimately lead to the jth of n = 3 outcomes (for the case at hand) with probability dij. Thus, the matrix D may constitute a social theoretical summary of the deliberation process. (For a detailed discussion of social decision scheme theory, see Davis, 1973, 1980; Stasser, Kerr, and Davis, 1980; and Stasser, Kerr, and Bray, 1982.)

In general, social decision scheme theory is a means of connecting the probability distribution, p = (pG, pNG), of individual jurors' verdict preferences with the outcome distribution, P = (PG, PNG, PH), of juries by means of summary assumptions about the social process implicit in D, which are only imperfectly observable in most circumstances. Empirical estimates, ![]() and

and ![]() , are sometimes available but usually for only a few mock jury studies!

, are sometimes available but usually for only a few mock jury studies!

Before evaluating the effects of size and social decision scheme in light of various changes in juror guilt preferences, it might be useful to note that the present approach deals only with procedural, not distributive, justice. Moreover, correctness of verdict is not at issue. The true verdict, guilty or not guilty, is unknown. There is no probability attached to that event, and we have no means of discovering it in any case.

Thought Experiments: Jury Size and Assigned Decision Rule. In order to make projections about the effects of different jury sizes, it is necessary to assume something about the social decision scheme. Consequently, consider Table 9-2 again. The middle two matrices in each row of the table represent idealizations of a two-thirds majority rule, differing only in the way nonmajorities are treated. In one case, if a two-thirds majority does not exist, then the jury is as likely to choose guilty as not guilty; in the other, observe that the lack of a two-thirds majority results in a hung jury with a probability near 1.00. (Since entries are probabilities, values of 1.00 and 0.00 should be regarded as very near 0 or 1.) Some jury sizes, of course, require some further rounding (for example, note that two-thirds majorities are imperfectly realizable in a jury of ten persons).

Next, matrices in the first and last columns of Table 9-2 represent less familiar social decision schemes. Arrays in the first column reflect a proportionality principle, and those in the last a majority of sorts, but one with a dependent protection bias—a tendency actually observed in six-person mock juries (Davis, Stasser, Spitzer, and Holt, 1976; Davis and others, 1977). The first and last matrices for nine- and twelve-person juries are idealizations or extrapolations from the six-person cases. Thus, they represent plausible conjectures to aid us in illustrating verdict outcomes with juries not operating on the tidier (and more nearly symmetrical) social decision schemes implied by such phrases from conventional wisdom as majority rules.

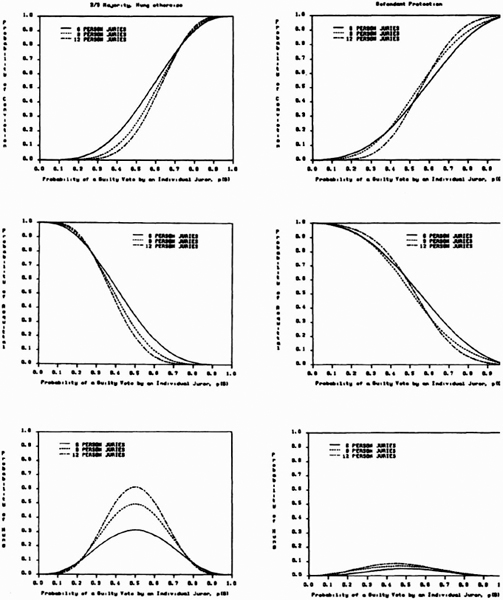

Calculations have been carried through using the social decision schemes of Table 9-2. Figure 9-1 shows PG, PNG, PH as a function of pG for juries of six, nine, and twelve. The role of size is perhaps even more evident in Figure 9-2, left-hand panel, which assumes for purposes of our comparisons here a simple majority social decision scheme and only two out-comes (guilty, not guilty), chosen with equal probability if no majority exists. The right-hand panel of Figure 9-2 also reflects a simpler task (guilty or not guilty verdicts) but demonstrates for twelve-person groups the effect of three different social decision schemes on the probability of a conviction as a function of the probability a juror will vote guilty.

Table 9-2. Possible Social Decision Scheme Matrices for Criminal Juries.

Note: G = guilty, NG = not guilty, H = hung jury.

Figure 9-1. Thought experiments showing the probability of conviction, PG (first row), acquittal, PNG (second row), and hung, PG (third row), as function of individual jurors voting for a guilty verdict. The curves on each panel reflect juries of different size (six, nine, and twelve). The four panels in each row correspond exactly to the four social decision schemes defined by the four columns of matrices of Table 9-2—informally labeled Proportionality; Two-thirds Majority, Otherwise Hung; and Defendant Protection (suggested by empirical data).

Figure 9-2. The left-hand panel shows the probability of conviction as a function of juror guilt preferences for various jury sizes, under the assumption of a simple majority; otherwise guilty or not guilty verdicts are returned with equal probability. The right-hand panel shows the same for twelve-person juries, but operating on simple majority, two-thirds majority, or proportionality (that is, the probability of an outcome is the proportion of members advocating it)

Perhaps the most obvious conclusion evident from Figures 9-1 and 9-2 is that no single answer satisfies the question “What is the best size for a criminal jury?” When the probability of a guilty vote by an individual juror is small, the smaller jury is more likely to convict than the larger. Under most prevailing philosophical dispositions, this would suggest that the larger jury is a better choice than the smaller one; convicting the innocent is a more serious error than acquitting the guilty. When the probability of an individual voting guilty is high, the twelve-person jury is more likely to convict than, say, a six-person jury. Again, given the usual philosophical dispositions for protecting the defendant, the smaller jury might be regarded as superior to the larger, although some might favor the converse in “society's interests.” Notice in Figure 9-1 that the larger jury is more likely to hang than a smaller one, particularly for very close cases (that is, pG ![]() .50).

.50).

Figures 9-1 and 9-2 also imply an important lesson for the conduct of empirical research intended to address the question of optimum size. A study (for example, a mock trial) with a case disposing jurors to respond such that pG is small will yield one result, whereas a separate study using a case causing pG to be large will yield a quite different result. This illustrates another important point. Thought experiments not only require data upon which to base model parameters (for example, the D matrix of the social decision scheme model), they can also help guide the collection of new data. The application of the two-thirds majority–hung otherwise decision scheme in Figure 9-1 suggests that the major impact of reducing jury size could be to reduce the rate of hung juries when cases are very close. Further, all the thought experiments to date suggest that jury size effects are rather small by typical social research standards. These conclusions suggest that previous studies of jury size may have generally failed to find any effect on jury verdicts (Hastie, Penrod, and Pennington, 1983) because their sample sizes were too small to detect such effects, their cases were not close enough, and/or they didn't examine the appropriate outcome measure (namely, hung jury rate). With these suggestions in mind, Kerr and MacCoun (1985) empirically reexamined the effects of mock jury size. But in contrast to previous work, they restricted their attention to rather close cases, focused mainly on hung jury rates, and made every effort to maximize the power of their tests. And, as suggested by the thought experiments reviewed above, Kerr and MacCoun found that for very close cases, mock jury size was directly and significantly related to hung jury rates, while there was no significant relation between jury size and conviction/acquittal rates. Thus, while research that was largely unguided by theory suggested that jury size did not affect deliberation outcome, research guided by thought experimentation (based on available theory and research) suggested quite a different conclusion. (See also Nagao and Davis, 1980, for further discussion of small effects and sample sizes in social research.)

The concern with jury size, like that of assigned decision rule, arose largely after Supreme Court decisions (Colgrove v. Battin, 1973; Williams v. Florida, 1970; Ballew v. Georgia, 1978). Overall, there seems to be little to support the notion of reducing jury size. Besides the antidefendant bias inherent in a reduction in overall hung jury rates (compare Kerr and others, 1976), it can also be shown (for example, Lempert, 1975) that reducing jury size also has pronounced and adverse effects on jury representativeness. Others (for example, Hastie, Penrod, and Pennington, 1983; Tanford and Penrod, 1983) have explored the effect of varying the jury's assigned decision rule through thought experimentation. Their primary finding—that nonunanimous juries are less likely to hang, especially for very close cases—has also been empirically confirmed (for example, Kerr and others, 1976). Many commentators have viewed with considerable distress, even alarm, the tendency of the criminal jury in the United States to decrease in size and the relaxation of the assigned decision rule (for example, Zeisel, 1971; Lempert, 1975). Thought experimentation has clearly guided empirical work to identify the small but nevertheless important effects of these changes in the jury system.

Summary. The relative unpopularity of group size research has been noted repeatedly. Research on the effect of assigned or institutionally imposed decision rules has, if anything, been even less popular. Thought experiments, such as the examples discussed above, provide an important supplement to the verbal theories that have heretofore been the only aid to conventional wisdom. Increases in group size tend generally to accentuate, in the group decision distributions, whatever perturbations exist in the individual decision preference distributions and to increase the probability of a hung jury. Reducing the level of consensus required for a verdict not only decreases the likelihood of a hung jury, it also has a similar effect of accentuating individual preferences. The outcome to be expected from changes in both simultaneously is not simple and not intuitively obvious.

We should also note that, in principle, there is no reason why size and assigned rule effects like those discussed here should be restricted to juries. Other task-oriented groups whose decision-making process can be accurately summarized by D matrices in similar fashion should exhibit similar effects. In particular, the jury-inspired social decision scheme matrices seem likely to provide at least a fair summary for groups in which each member has roughly equal formal power, in which initial majorities usually win, and which are more likely to deadlock as the initial split between subgroups or factions becomes more nearly equal in size. Intuition and theory (for example, Laughlin and Adamopoulos, 1982) suggest that this includes a very wide range of common decision-making groups located in a wide range of organizations and institutions.

Jury Selection

Between the abstract concept of a jury—a group of lay-persons, untrained in the law, acting as referees of fact—and the realization of that concept lie a series of juror selection procedures. Juror selection is a multistaged, complex process that varies considerably across jurisdictions (Hans and Vidmar, 1982; Van Dyke, 1977). There are certain common features, however. First there must be legislation defining eligibility rules (for example, citizenship, fluency in English), rules governing waiver of service (for example, to certain professions like police officers and physicians), and terms of duty (varying from one day/one trial to several weeks). A local official must maintain a list of potential jurors (most commonly based on voters' registration lists). Then a panel of potential jurors must be assembled at the court for final selection procedures. In all common-law countries those who have a demonstrable bias (for example, a relationship with a litigant or a personal interest in the outcome of the case) must be excluded; this is termed a challenge for cause. And in U.S. courts, opposing counsel are also given several additional “peremptory” challenges that may be exercised without explanation or justification.

A relatively new feature in jury selection is the use of social science methods to assist attorneys. A number of procedures, collectively referred to as scientific jury selection (SJS), have been used systematically by some (namely, Kairys, Schulman, and Harring, 1975; Schulman and others, 1973) in an attempt to secure advantage for, in these instances, the defense. For example, entire jury panels have been challenged using statistical data that establish that they are unrepresentative of the population of potential jurors (for example, Castaneda v. Partida, 1977; Michaelson, 1980). Another technique has been to provide evidence in support of a change in the location or venue of a trial. For example, social scientists have collected public opinion data using survey methods to support the argument that there is a general bias against a defendant in a particular locale (for example, due to extensive pretrial publicity—McConahay, Mullin, and Frederick, 1977; Vidmar and Judson, 1981). And an elaborate and controversial (for example, Berk, Hennessy, and Swan, 1977; Berman and Sales, 1977; Etzioni, 1974; Spector, 1974) technology has been developed to assist attorneys in the exercise of their challenges (for example, Schulman and others, 1973). These techniques include (1) investigating individual potential jurors through their neighbors, acquaintances, or other members of the local community; (2) surveying public opinion on key trial issues to develop demographic and attitudinal profiles of jurors favorable and unfavorable to one's case; and (3) using expert consultants in court to evaluate potential jurors' verbal and nonverbal behavior. Because of the expense involved, such techniques have been employed mostly in major cases that have attracted considerable public attention and support (for example, the Wounded Knee trial, the Joan Little trial).

In addition to the controversy concerning the ethics of SJS in practice, there is also disagreement about the effectiveness of such techniques (Berman and Sales, 1977; Saks and Hastie, 1978). Of course, the ethical and practical problems associated with a thorough empirical evaluation of SJS's effectiveness are enormous, and it is not surprising that none has been under-taken. Again, thought experiments offer a useful supplement to empirical research.

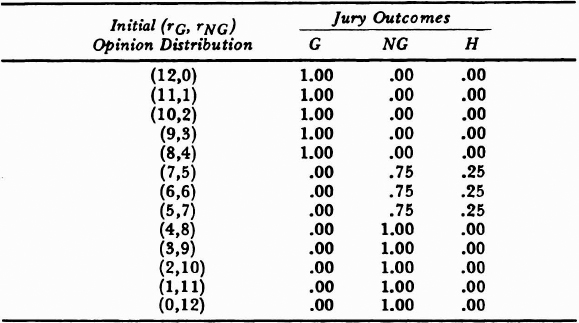

Thought Experiments: Scientific Jury Selection. Tindale and Nagao (1984) have carried out several thought experiments to explore the likely effects of SJS under various scenarios. First, they note that proponents of SJS (for example, Schulman, 1973) feel that SJS may be most valuable in helping to win changes of venue. So, the first issue Tindale and Nagao addressed was, how much impact on jury verdicts might be reasonably attributed to a change of venue? Of course, such effects would depend in part upon how different the jurors were in the venues in question. Tindale and Nagao contrasted three hypothetical venues: one in which only a large majority of jurors favored conviction (80 percent voting for guilty, 20 percent voting for not guilty); one containing a substantial minority favoring acquittal (60 percent guilty; 40 percent not guilty); and one for which there was equal support among individual jurors for conviction and acquittal (50 percent guilty; 50 percent not guilty). They assumed that twelve-person juries were randomly composed from each venue's juror population and that their deliberation process was summarized by a “two-thirds majority—defendant protection otherwise” social decision scheme, which is presented in Table 9-3. Such a matrix combines elements of the two-thirds majority–hung otherwise and majority with defendant protection schemes presented earlier in the third and fourth columns of Table 9-2. Asymmetric social decision schemes favoring the defendant have frequently been observed in mock trial studies (for example, Davis and others, 1975, 1977; Kerr and others, 1976).

Table 9-3. Social Decision Scheme for Twelve-Person Juries.

Note: G = guilty, NG = not guilty, H = hung jury. Principle: Two-thirds majority establishes guilty, not guilty verdict with probability near 1.0, otherwise P(NG) = .75, P(H) = .25

Source: Adapted from Tindale and Nagao (1984), with permission.

Figure 9-3 shows the results of Tindale and Nagao's thought experiment. Focusing on the acquittal rates, we see that under their assumptions, jury acquittal rates would range from 5 percent (in the venue where 20 percent of the jurors acquit), to 44 percent (in the 40 percent juror acquittal venue), to 64 percent (when half of the jurors acquit). Thus, a venue-based difference of only 30 percent in individual acquittal rates would, under reasonable assumptions, translate into a striking 59 percent difference in jury acquittal rates due to change of venue. Clearly, even small between-venue differences can have dramatic effects on trial outcomes.

Figure 9.3. Predicted jury verdict consequences as a result of a change in venue.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Tindale and Nagao, 1984.

Tindale and Nagao next considered the impact that SJS might have during the juror selection phase of the trial. Assuming for the moment that SJS techniques have at least some validity, they asked how much “better” could a hypothetical defense counsel expect to do in a trial having used SJS than not using these procedures? In particular, Tindale and Nagao made the modest assumption that the net consequences of all SJS procedures affected by the defense attorneys would be to ensure that the jury would have one more advocate for acquittal than it would have had without using SJS techniques. Again they assumed that twelve-person juries were randomly composed and deliberated under the same decision scheme as before. The results of their thought experiment appear in Figure 9-4 as a function of the probability, pG, that an individual juror votes for conviction. Clearly, when the case is lopsided (that is, pG is near 0.0 or 1.0), SJS would not have much impact, but for more uncertain cases (that is, pG ![]() . 50) it could have a fairly substantial effect (reaching a maximum effect of 19 percent for cases that are moderately strong against the defendant). One can easily imagine the difficulty of establishing this result through empirical study alone, unguided by theory. However, thought experiments (such as those of Tindale and Nagao) could help focus research effort and more efficiently use resources (for example, subjects) by suggesting research targets that would be most likely to yield an effect, as well as its likely magnitude.

. 50) it could have a fairly substantial effect (reaching a maximum effect of 19 percent for cases that are moderately strong against the defendant). One can easily imagine the difficulty of establishing this result through empirical study alone, unguided by theory. However, thought experiments (such as those of Tindale and Nagao) could help focus research effort and more efficiently use resources (for example, subjects) by suggesting research targets that would be most likely to yield an effect, as well as its likely magnitude.

Figure 9-4. Predicted not guilty verdict consequences of scientific jury selection adding one not guilty juror to the jury as a function of strength of evidence against the defendant

Note: Reprinted with permission with Tindale and Nagao, 1984.

Thought Experiments: “Nonscientific” Jury Selection. The actual practice of juror selection stands in sharp contrast to the prescriptions of SJS. Observational research (for example, Broeder, 1965) has shown that in the average trial, examination of potential jurors is cursory and few if any of the available peremptory challenges are used. Further, the average attorney does not generally have the wealth of data on jurors generated by SJS. Rather, counsel must usually rely on superficial background characteristics that can be obtained through casual observation or questioning (for example, juror sex, occupation, ancestry). Although there exists an extensive folklore among lawyers attesting to the utility of such factors (for example, Bailey and Rothblatt, 1971), direct empirical research (for example, Penrod, 1979; Saks, 1976) suggests that such factors show, at best, a very weak relationship with verdict.1

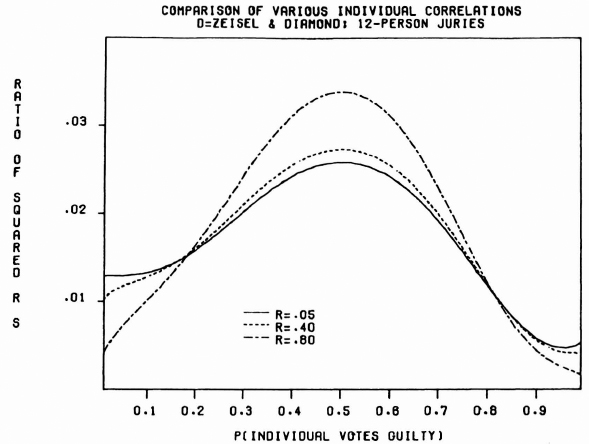

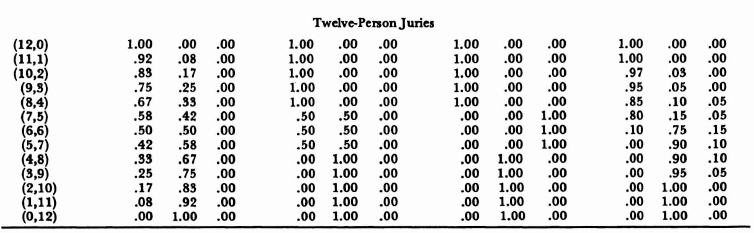

Under typical constraints, just how much impact on jury verdicts can an attorney expect to have by recognizing a potential source of bias in a juror and exercising a challenge to eliminate that juror? In a recent series of thought experiments, Kerr and Huang (1984) explored this issue. Suppose some individual juror characteristic, X, is related to individual verdicts, as indexed by a product moment correlation coefficient rj. Kerr and Huang asked the following question: How well would knowledge of one juror's status on X predict the verdict of his or her jury?

In their initial thought experiment, Kerr and Huang assumed that juries deliberated under a social decision scheme suggested by Zeisel and Diamond's (1978) observations of actual juries. That scheme is presented in Table 9-4. One can see that it is similar to some of the previously discussed schemes: Large initial majorities usually prevail, hung juries are more likely when the jury is initially evenly split, and there is some indication of a prodefendant bias (although it is less pronounced than for some of the social decision scheme matrices that have been observed in mock jury studies, for which deliberation times are often limited). Kerr and Huang compared the amount of variance accounted for in jury verdicts (that is, r2Jury, where rJury = the correlation between a juror's status on X and the jury's verdict) with the amount of variance X accounts for in individual jurors' verdicts (namely, rI2). (See Kerr and Huang, 1984, for computational details.)

Table 9-4. Zeisel and Diamond's Decision Scheme.

Note: G =guilty, NG =not guilty, H =hung jury.

In Figure 9-5 we see the ratios of these two squared correlations as a function of the overall conviction rate for individual jurors, pG, and the strength of X as a predictor (that is, rI). As in Tindale and Nagao, the ratio is highest when the case is close; when the case is lopsided, knowledge of even a valid predictor of a juror's verdict is of less utility in predicting the jury's verdict. Also, unsurprisingly, the larger the value of rI, the larger is the ratio, except for very lopsided cases. But the most important finding is that one can account for so little of the variance injury verdicts from knowledge of a juror's status on X; under the present assumptions, the ratio was always less than .04. However, this result is consistent with the perennial finding that member personality traits are very poor predictors of group performance (Mann, 1959; Heslin, 1964), an empirical result usually attributable to poor assessment techniques, dependent as they are on questionnaire answering. However, the above results suggest that there may be a limit on the predictability of group outcomes from trait knowledge (at least using indices of linear relationships) that has a more complex origin than suspected heretofore. (See also the discussion by McGrath and Altman, 1966.)

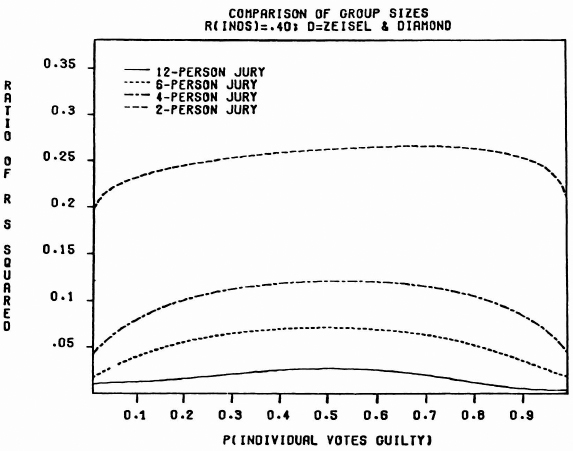

Earlier we explored the effect of jury size on deliberation outcome. Similarly, Kerr and Huang examined the relevance of jury size for the current question by means of a thought experiment. They generalized from the decision scheme implied by Zeisel and Diamond's (1978) observations, discussed earlier, for one group size (namely, twelve-person juries) to other jury sizes (namely, six-, four-, and two-person groups). For this thought experiment, they also assumed that X was a moderately strong predictor of individual juror verdict preferences (specifically, that rI = .40). Results are given in Figure 9-6. As intuition would suggest, a juror's characteristic became more predictive of the group's verdict as jury size decreased; but somewhat counter to intuition, it was never possible to predict more than about a quarter as much variance for the jury as for the juror, even in dyads.

Figure 9-5. Ratio of variance accounted for in a jury of twelve persons to variance accounted for in individual juror verdict preferences as a function of strength of evidence against the defendant and strength of the predictor of individual juror verdicts.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Kerr and Huang, 1984.

Figure 9.6 Ratio of variance accounted for in the jury (of two, four, six, and twelve persons) to variance accounted for in juror verdict preferences as a function of strength of evidence against the defendant and jury size (rI = .40, and the matrix D taken from Zeisel and Diamond, 1978).

Summary and Implications. The preceding thought experiments demonstrate that different ways of approaching jury selection have rather different implications, some of which are counterintuitive. Even small differences between juror populations are exaggerated when one contrasts juries composed exclusively of members of one population with juries composed exclusively of those from another. On the other hand, even strong predictors of an individual juror's verdict preference will be far less useful in predicting the verdict of the jury of which that person is a member.

As noted earlier, it is important to recognize that the thought experiments discussed here have broader relevance than for jury behavior alone. Indeed, the results reported above have implications for various decision-making groups or committees whose deliberation processes can be reasonably summarized by the social decision schemes applied here and the conditions assumed in these conceptual studies. For example, a personnel manager can expect an exaggeration among decision-making committees of even relatively small differences in opinion found between alternative pools of committee members. Thus, one cannot reasonably expect to change the decisions of a committee very much by changing one committee member, A, for another, B—even if it is known that A and B hold opinions that differ a great deal. (Of course, such a conclusion would perhaps have to be modified under different conditions—changes in agenda structure, leader-follower relations, and so on.)

Organizational Structure and Decision Making

A fundamental problem in organizations is how to structure the system to best satisfy the organization's goals. For many organizations, these goals include reaching decisions that accurately and honestly reflect the preferences of the organization's members. Potentially relevant factors to be engineered include the number, size, and composition of constituent units in the organization and the formal (or informal) consensus criteria that apply at various levels of the organization (for example, the applicable decision or voting rules). The importance of such factors continues to be a matter of some controversy, not unlike the continuing debate about runoff elections in state primaries.

One approach to such questions, particularly popular in some areas of economics, has been to develop highly formal, axiomatic models of social choice (for example, Arrow, 1963). Social choice models (for example, Fishburn, 1973) resemble social decision scheme models in that they aim to translate individual decision preferences into group decisions. The two approaches differ in that social choice models typically work with a preference order (a set of ranked decision alternatives) and generally are not as concerned with the psychological plausibility of their assumptions; the latter concern with normative models usually leads to simulations that discover which group decisions (preference orders) are possible, desirable, optimal, and so on under various interesting conditions. Both approaches have much to offer in connection with thought experiments, depending upon one's purposes. (Indeed, descriptive and normative research efforts have independent and supplementary contributions to make to our understanding of group performance in general.) However, we are interested here in extending the social decision scheme model (especially those special cases that have been well supported in past, somewhat similar applications) to the organizational levels question implied above; that is, we will explore the behavior of the “flow of decisions” in hierarchically structured organizations composed of small, decision-making groups by means of thought experiments. Obviously, we must work with an idealized organization for this purpose but recognize that actual organizations are likely to be much less orderly in both structure and process.

Thought Experiments: Minority Size, Minority Integration, and Decision Process. Davis's (1973) exploration of the effect of several alternative social decision processes for final organizational decision offers a useful initial illustration. That investigation showed that if the original distribution of individual preferences was nonuniform, if the organization had a simple hierarchical structure (such that the decision made at one level would be carried on by that group's representative and advocated in the group at the next highest level), and if the decision-making process of groups at every level of the organization could be summarized by a common decision scheme (namely, a plurality determines the group choice), then the net effect of the process of moving from individual members' preferences to the final organizational decision would be to exaggerate at the top (the final distribution of group decisions) the strength of preference at the bottom of the organization. That is, the initially more popular alternatives become even more popular and the less preferred alternatives become less preferred still as the information (decision distribution) ascends the levels. If the organization has enough levels, minority preferences can be almost entirely suppressed. The thought experiment also demonstrated that different group decision processes (summarized by different social decision schemes) would produce rather different effects. Various sorts of plurality schemes summarize decision processes for which there is strength in numbers, but depending on task demands and social context, among other things, quite different social decision processes are likely to emerge. (See Davis, 1982, for a discussion of social decision schemes as a function of task types.) One process that seems to characterize intellective tasks with no immediately obvious answer (for example, Davis, Hornik, and Hornseth, 1970) is the equiprobability scheme, which holds that all alternatives with at least one advocate are equally likely to be the group's choice. It turns out that such a decision scheme tends to level the distribution of preferences, an effect that is compounded in a multi-leveled hierarchically structured organization—the leveling progressing as the hierarchy is ascended. Finally, we may note that it is also possible to preserve the original distribution of individual preferences as the decisional information flows upward in the organizational hierarchy as described above. Such preservation is maintained by a proportionality social decision scheme, for which the probability of the group adopting an alternative is equal to the relative frequency of advocates for a position.

The levels effect of the social decision processes just described is illustrated in Figure 9-7. In addition, the consequences of an averaging social decision scheme (the group choice is the arithmetic mean of the positions advocated) are shown for purposes of comparison. Clearly, the way interaction effectively aggregates member choices, as well as the number of levels to be traversed within the organization, exerts a powerful influence on the form of the information finally available at the top of the hierarchy. Observe, once more, that the degree of distortion (in the sense of inaccurately reflecting the grass-roots opinion) that may characterize the final distribution can be the consequence of a straightforward, sincere, democratic process, and in practice may go unrecognized by organization members.

The thought experiments just described assumed a single underlying population of individuals in the organization—a fairly unlikely lack of individual differences. Indeed, it is a more plausible assumption that an organization has several distinct subpopulations, possibly with different preference functions for each. Organizations also may differ in the organizational level at which their various subpopulations are integrated. In some cases, only units at the bottom of the organizational hierarchy may be homogeneous with respect to subpopulation membership—just as there may be less interpersonal variability within than between precincts in elections. In other cases, there may be more thorough integration of subpopulations throughout the organizational hierarchy.

Using a thought experiment, Ono and Hulin (1984) recently extended earlier (Davis, 1973) analyses to examine the impact of minority group integration in an organizational structure. In the interests of simplicity, they assumed that there were just three ordered decision alternatives, A1, A2, and A3, and two subpopulations—a majority subpopulation that most strongly preferred alternative A1, where the distribution of individual preferences was given by the probability vector pM = (.433, .333, .233), and a minority subpopulation in which A3 was the most preferred alternative, given by pm = (.050, .100, .850). They further assumed five-person groups meeting at each level of a five-level organizational hierarchy. Again, the distribution of group decisions at one level was taken as the distribution of individual preference at the next higher level. Finally, Ono and Hulin contrasted three decision schemes: strict equiprobability (STEQ); plurality if one exists, equiprobability otherwise (PLEQ); and plurality if one exists, proportionality otherwise (PLPR). Due to the inherent constraints of a five-person group choosing from among three alternatives, all pluralities were also majorities; therefore, PLEQ = MAEQ (majority wins if one exists, equiprobability otherwise). Similarly, PLPR = MAPR.

Figure 9-7. The initial individual and group distributions of decisions at each level of an organization for each of several common social decision schemes.

Five alternative models of minority integration were examined. They are depicted in Figure 9-8. Model A has complete subpopulation integration throughout the organization. Succeeding models retain subpopulation segregation at ever higher levels of the organization, such that by model E, representatives of the two subpopulations do not join the same group until the fifth and highest level. A final parametric variation in Ono and Hulin's thought experiment was the size of the majority; the majority subpopulation was assumed to represent 60 percent, 70 percent, 80 percent, or 90 percent of all the individuals in the organization and identical percentages of groups at the segregated levels of models B through E.

Figure 9-8. Alternative models for integration of minority and majority subpopulations in a hierarchical organization.

Note: Reprinted with permission from Ono and Hulin, 1984.

The thought experiment's results are plotted in Figure 9-9 in terms of the level of support by the final level of the organization for alternative A3, the minority's most preferred alternative. Several patterns are evident. First, integration model and majority size are irrelevant under a STEQ decision rule; as noted above, this type of group decision process tends to produce a uniform preference distribution, and repeating its effect five times as in the present thought experiment completely flattens the preference function (that is, under STEQ, alternative A3 is favored 33 percent of the time at the top of the organization). Second, and unsurprisingly, under more plausible decision processes (namely, majority or plurality wins), as the minority gets smaller, its preference becomes less likely to survive the organizational decision-making process. Third, and most importantly, as long as the minority is not too small, the more fully integrated the organization is, the more likely minority preference is to be reflected at the top of the organization.

Summary and Implications. Many, if not most, organizations are hierarchically organized. And it is not uncommon for there to exist some degree of segregation of distinctive subpopulations within organizations. Conventional wisdom holds that minorities will have more impact on the organization's decision by electing their own representative (that is, by maintaining segregation of group composition at lower organizational levels). But Ono and Hulin's analysis suggests that under familiar group decision processes, quite the opposite is true—minority opinion is more likely to emerge by fuller integration of the minority with the majority.2 Of course, as in all thought experiments, the usefulness of results depends upon the plausibility of the generating assumptions. Further simulations under alternative assumptions will in time add to our store of information.

The Thought Experiment as a Method of Research

Utility of Thought Experiments. We have tried to show in the preceding sections that thought experiments can serve a number of useful functions. First, they can reveal unanticipated regularities or complexities in behavior. Ono and Hulin's findings on minority integration nicely illustrated this point. Second, they can identify the most informative or important range of parameters for direct empirical study. For example, Kerr and MacCoun's (1985) recent study of jury size used the findings of previous thought experiments to identify the types of cases and measures that should (and did) yield a jury size effect. Third, they can provide methodological aids. Kerr and Huang's thought experiments point out the apparent futility of drawing strong inferences about the strength of predictors of individual decision-making behavior when one can only obtain group decisions. Such thought experiments could also be used to develop normative baselines as methodological tools. For example, suppose one is interested in determining whether a single group member from a population of interest (for example, a juror who has encountered some prejudicial pretrial publicity) has disproportionate influence on the group outcome. The techniques used by Kerr and Huang would enable one to predict groups' decisions under the assumption that group members are indistinguishable except for their preferences. Deviations from this prediction in the direction of the distinctive member (for example, higher than predicted conviction rates for the pretrial publicity example) would disconfirm the equal-influence assumption. Finally, thought experiments can aid in theory development. Alternative social decision schemes can plausibly be viewed as alternative special-case theoretical models of the group decision-making process, with implicit assumptions about social influence processes. Further, they have the virtue of providing point predictions, which permits more nearly decisive falsification, and perhaps subsequent model revision and improvement (Kerr, Stasser, and Davis, 1979).

Note: Reprinted with permission from 000 and Hulin, 1984.

It is also important to reemphasize that we are not advocating thought experiments as a substitute for data. Ideally, a thought experiment, like any conceptual tool, must be consistent with the relevant data, when they exist. Rather, we advocate thought experiments as an adjunct and guide to data collection and theory development, which can be particularly useful at the early stages of inquiry, especially for questions with unusual ethical or practical barriers to thorough empirical study.

General Prescriptions for Thought Experiments. The greatest impediment to further exploitation of thought experimentation is the scarcity of suitable theory. This approach generally requires explicit, formal mathematical or computer models. Unfortunately, the norm in the social and organizational sciences is the conceptual model that is cast largely or entirely in verbal terms, which may be interesting and provocative but typically yields only predictions, at best. Indeed, it is quite common for verbal models of social behavior to permit several formal mathematical versions, at least some of which may make contradictory predictions. (See Harris, 1976, for a thorough discussion and illustrations.)

Again, the results of a thought experiment are no more valid than its assumptions. For this reason, whenever possible, thought experiment assumptions should be empirically tested. Even though there may be instances where one can perform useful thought experiments even when assumptions cannot be checked empirically, our confidence in the results will generally be directly proportional to the quality of the empirical support for key assumptions. Thus, we have a considerable measure of confidence in the jury thought experiments described above, since empirical research has strongly supported the form of the social decision schemes they employ. But since we have very little good data on the nature of the decision-making process within large multileveled organizations, we must be more guarded about the general applicability of Ono and Hulin's simulation at this time. On the other hand, we have noted above that it is precisely at this early stage that thought experiments can be especially useful.

Finally, mindful of the inherent weakness of thought experimentation, one should make every effort to capitalize on its strengths. At relatively little cost, one can vary parameters through quite wide ranges and include many different special cases or versions. Such parameter variation not only permits one to explore the robustness and generality of results but also helps increase the chances for making interesting new discoveries, perhaps unexpected. For example, had Hulin and Ono been content to restrict their attention to very small minorities, we would not have their interesting results on minority integration.

Closing Thoughts

There are frequent disappointments in the application of social research results to various problems, whether from an engineering or evaluation perspective. We have been stressing here a better marriage between theory and data, a match that heretofore has perhaps favored data gathering. We argued earlier that it is often unlikely that sufficient data will be available or forthcoming in view of the phenomena with which social psychology must deal. Actually, the problem is rather general, as has been noted by Boulding (1980): “Empirical regularities sometimes lead to the discovery of theoretical necessities, as happened in celestial mechanics, but science can never be satisfied with empirical regularities unless it can discover the theoretical necessities behind them. The idea that science consists merely in the discovery of empirical regularities is a total misunderstanding of its methods and its power. Without logical necessity, empirical regularity is little better than superstition” (p. 834). It is our thesis that the same disposition to search for empirical regularities without a parallel appreciation of theory lies behind many current difficulties in application, especially those involving task-oriented groups within organizations and institutions.

In a sense thought experiment is another name for simulation or the logical exploration of models—but perhaps a label that better captures the idea of extrapolating from data or social practice. Abelson's (1968) summary of simulation and its virtues conveys much the same spirit. For example, “Simulation is the exercise of a flexible imitation of processes and outcomes for the purpose of clarifying or explaining the underlying mechanisms involved. The feat of imitation per se is not the important feature of simulations, but rather that successful imitation may publicly reveal the essence of the object being simulated” (p. 275).

We conclude by noting that program evaluation has been highly successful during the past decade. Policymakers now routinely expect assessment data to be part of the tools available for decision making. Part of the success of program evaluation may be attributed to research methods that make possible the efficient handling of large data sets and large-scale analyses. The notion of organizational and institutional accountability provided an additional stimulus for public agencies, policies, and programs to be evaluated. The result has been a strong commitment to gathering empirical data to replace intuitive conclusions about the effects of social policy and programs—intuitions often influenced by political ideology and conventional wisdom.

Just as the program evaluation revolution provided the means of improving decisions about current institutions, policies, and so on, so might one hope that simulations, which we have camouflaged here as thought experiments, might provide a social engineering revolution, of sorts, about proposed organizational changes. Formal models have moved scientists and policymakers alike from data to orderly projections in areas varying from economics to meteorology—in just the fashion suggested (and illustrated) herein—but rarely in social and organizational psychology. (Gelfand and Solomon, 1973, and Penrod and Hastie, 1979, are among the striking exceptions.) However, there may be little alternative in the years ahead to the use of thought experiments to improve on hunches and ideologically derived policies and programs, especially those involving potentially “expensive” changes to sensitive institutions such as the jury.

References

Abelson, R. P. “Simulation of Social Behavior.” In G. Lindzey and E. Aronson (eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol. 2. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1968.

Apodaca and others v. Oregon. United States Supreme Court Reports, 1972, 406, 404–415.

Arrow, K. J. Social Choice and Individual Values. New York: Wiley, 1963.

Bailey, F. L., and Rothblatt, H. B. Successful Techniques for Criminal Trials. New York: Lawyers Cooperative, 1971.

Ballew v. Georgia. United States Law Week, 1978, 46, 4217–4224.

Becker, T. L., Hildrun, D. C., and Bateman, K. “The Influence of Jurors' Values on Their Verdicts: A Courts and Politics Experiment.” Southwestern Social Science Quarterly, 1965, 45, 130–140.

Berk, R. A., Hennessy, M., and Swan, J. “The Vagaries and Vulgarities of ‘Scientific’ Jury Selection.” Evaluation Quarterly, 1977, 1, 143–158.

Berman, J., and Sales, B. “A Critical Evaluation of the Systematic Approach to Jury Selection.” Criminal Justice and Behavior, 1977, 4, 219–240.

Boulding, K. E. “Science: Our Common Heritage.” Science, 1980, 207 (4433), 831–836.

Bray, R. M., and Kerr, N. L. “Methodological Considerations in the Study of the Psychology in the Courtroom.” In N. Kerr and R. Bray (eds.), The Psychology of the Courtroom. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1982.

Broeder, D. “The Negro in Court.” Duke Law Journal, 1965, 19–31.

Castaneda v. Partida. United States Supreme Court Reports, 1977, 430, 482.

Colgrove v. Battin. United States Supreme Court Reports, 1973, 149, 413.

Davis, J. H. “Group Decision and Social Interaction: A Theory of Social Decision Schemes.” Psychological Review, 1973, 80, 97–125.

Davis, J. H. “Group Decision and Procedural Justice.” In M. Fishbein (ed.), Progress in Social Psychology. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1980.

Davis, J. H. “Social Interaction as a Combinatorial Process in Group Decision.” In H. Brandstatter, J. H. Davis, and G. Stocker-Kreichgauer (eds.), Group Decision Making. London: Academic Press, 1982.

Davis, J. H., Bray, R. M., and Holt, R. W. “The Empirical Study of Decision Processes injuries: A Critical Review.” In J. L. Tapp and F. J. Levine (eds.), Law, Justice, and the Individual in Society: Psychological and Legal Issues. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1977.

Davis, J. H., Hornik, J. A., and Hornseth, J. P. “Group Decision Schemes and Strategy Preference in a Sequential Response Task.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1970, 15, 397–408.

Davis, J. H., Stasser, G., Spitzer, C. E., and Holt, R. W. “Changes in Group Members' Decision Preferences During Discussion: An Illustration with Mock Juries.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1976, 34, 1177–1187.

Davis, J. H., and others. “The Decision Processes of 6- and 12-Person Juries Assigned Unanimous and 2/3 Majority Rules.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1975, 32, 1–14.

Davis, J. H., and others. “Victim Consequences, Sentence Severity, and Decision Processes in Mock Juries.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 1977, 18, 346–365.

Etzioni, A. “Creating and Imbalance.” Trial, 1974, 10, 28–30.

Fishburn, P. C. The Theory of Social Choice. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Gelfand, A. E., and Solomon, H. “A Study of Poisson's Models for Jury Verdicts in Criminal and Civil Trials.” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1973, 68, 271–278.

Gergen, K. J. “Social Psychology as History.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1973, 26, 309–320.

Gleisser, M. Junes and Justice. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1968.

Hans, V. P., and Vidmar, N. “Jury Selection.” In N. Kerr and R. Bray (eds.), The Psychology of the Courtroom. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1982.

Harris, R. J. “Handling Negative Inputs: On the Plausible Equity Formulae.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1976, 12, 194–209.

Hastie, R., Penrod, S., and Pennington, N. Inside the Jury. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1983.

Heslin, R. “Predicting Group Task Effectiveness from Member Characteristics.” Psychological Bulletin, 1964, 62, 248–256.

Johnson v. Louisiana. United States Supreme Court Reports, 1972, 406, 356–403.

Kairys, D., Schulman, J., and Harring, S. (eds.). The Jury System: New Methods for Reducing Prejudice. Philadelphia, Pa.: Philadelphia Resistance Print Shop, 1975.

Kerr, N. L., and Bray, R. M. “The Psychology of the Courtroom: An Introduction.” In N. Kerr and R. Bray (eds.), The Psychology of the Courtroom. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1982.

Kerr, N. L., and Huang, J. Y. “How Much Difference Does One Person Make in Group Decisions?: A Thought Experiment.” Paper presented at annual convention of American Psychological Association, Toronto, 1984.

Kerr, N. L., and MacCoun, R. J. “The Effects of Jury Size on Deliberation Process and Product.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1985, 48, 349–363.

Kerr, N. L., Stasser, G., and Davis, J. H. “Model Testing, Model Fitting, and Social Decision Schemes.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 1979, 23, 399–410.

Kerr, N. L., and others. “Guilt Beyond a Reasonable Doubt: Effects of Concept Definition and Assigned Rule on Judgments of Mock Jurors.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1976, 34, 282–294.

Laughlin, P. R., and Adamopoulos, J. “Social Decision Schemes on Intellective Tasks.” In H. Brandstatter, J. H. Davis, and G. Stocker-Kreichgauer (eds.), Group Decision Making. London: Academic Press, 1982.

Lempert, R. O. “Uncovering ‘Nondiscernible’ Differences: Empirical Research and the Jury-Size Cases.” Michigan Law Review, 1975, 73, 643–708.

McConahay, J., Mullin, C., and Frederick, J. “The Uses of Social Science in Trials with Political and Racial Overtones : The Trial of Joan Little.” Law and Contemporary Problems, 1977, 41, 205–229.

McGrath, J. E., and Altman, I. Small Group Research: A Synthesis and Critique of the Field. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1966.

Mann, R. D. “A Review of the Relationships between Personality and Performance in Small Groups.” Psychological Bulletin, 1959, 56, 241–270.

Michaelson, S. “History and State of the Art of Applied Social Research in the Courts.” In M. Saks and R. Baron (eds.), The Use/Nonuse/Misuse of Applied Social Research in the Courts. Cambridge, Mass.: Abt Books, 1980.

Nagao, D. H., and Davis, J. H. “Some Implications of Temporal Drift in Social Parameters.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1980, 16, 479–496.

Ono, K., and Hulin, C. L. “Simulation Study of Group Decision Making and Linking Pin Theory of Organization.” Paper presented at annual convention of American Psychological Association, Toronto, 1984.

Penrod, S. “Study of Attorney and ‘Scientific’ Jury Selection Models.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Harvard University, 1979.

Penrod, S., and Hastie, R. “Models of Jury Decision-Making: A Critical Review.” Psychological Bulletin, 1979, 86, 462–492.

Saks, M. “The Limits of Scientific Jury Selection: Ethical and Empirical.” Jurimetrics Journal, 1976, 17, 3–22.

Saks, M., and Hastie, R. Social Psychology in Court. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1978.

Schulman, J. “A Systematic Approach to Successful Jury Selection.” Guild Notes, Nov. 1973.

Schulman, J., and others. “Recipe for a Jury.” Psychology To-day, May 1973, pp. 34–44, 77, 79–84.

Spector, P. “Scientific Jury Selection Warps Justice.” Harvard Law Record, 1974, 55, 15.

Stasser, G., Kerr, N. L, and Bray, R. M. “The Social Psychology of Jury Deliberation: Structure, Process, and Product.” In N. L. Kerr and R. M. Bray (eds.), The Psychology of the Courtroom. Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1982.

Stasser, G., Kerr, N. L., and Davis, J. H. “Influence Processes in Decision Making: A Modeling Approach.” In P. Paulus (ed.), Psychology of Group Influence. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1980.

Tanford, S., and Penrod, S. “Computer Modeling of Influence in the Jury: The Role of the Consistent Juror.” Social Psychology Quarterly, 1983, 46, 200–212.

Tindale, S., and Nagao, D. “Some ‘Thought’ Experiments” Concerning the Utility of ‘Scientific Jury Selection.’” Paper presented at annual convention of American Psychological Association, Toronto, 1984.

Van Dyke, J. M. Jury Selection Procedures. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger, 1977.

Vidmar, N., and Judson, J. “The Use of Social Science in a Change of Venue Application.” Canadian Bar Review, 1981, 59, 76–102.

Williams v. Florida. Supreme Court Reporter, 1970, 90, 1893–1914.

Zeisel, H. “… And Then There Were None: The Diminution of the Federal Jury.” University of Chicago Law Review, 1971, 38, 713–715.

Zeisel, H., and Diamond, S. “The Effect of Peremptory Challenges on Jury and Verdict: An Experiment in a Federal District Court.” Stanford Law Review, 1978, 30, 491–531.

Note: This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation, grant SES 83–10797, to the University of Illinois, James H. Davis, principal investigator.

1. One should also note, though, that there are exceptions to this rule. For example, a number of studies indicate that female mock jurors are more likely to vote for conviction in a rape case than males (Nagao and Davis, 1980). Other special-case exceptions can also be identified (for example, Catholic as opposed to nonCatholic jurors in a euthanasia case; Becker, Hildrun, and Bateman, 1965).

2. Of course, it may be important for a minority to have its own representatives for other reasons: pride, ensuring that its position is force fully articulated, and so on. Different results are also possible under different assumptions, for example, fewer organizational levels, alternative decision schemes.