CHAPTER 2

Backwater to Mainstream: The Growth of Digital Entertainment

How did international conflicts spur the development of modern computers and the Internet?

What challenges do people face when creating content for a new medium?

Who was a more likely candidate to invent the first computer game: a physicist working with an oscilloscope or a teenage kid fooling around on a PC?

What effect is digital media having on traditional forms of entertainment like movies and TV?

AN EXTREMELY RECENT BEGINNING

The development of the modern computer gave birth to a brand new form of narrative: digital storytelling. Sometimes it is difficult to keep in mind that even the oldest types of digital storytelling are quite recent innovations, especially when compared to traditional entertainment media, like the theatre, movies, or even television. For instance, the first rudimentary video game wasn’t even created until the late 1950s, and two more decades passed before the first form of interactive storytelling for the Internet was developed. Most other types of digital storytelling are much more recent innovations. Thus, we are talking about a major new form of narrative that is barely half a century old.

While today’s children have never known a world without computers or digital entertainment, the same is not true for middle-aged adults. Individuals who were born before the 1960s grew up, went to college, and got their first jobs before computers ever became widely available. As for today’s senior citizens, a great number of them have never even used a computer and frankly aren’t eager to try. Almost certainly, though, they have taken advantage of computerized technology embedded in familiar devices, from microwaves to ATM machines to home security systems.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COMPUTER

While computers are newcomers to our world, only having been introduced in the middle of the twentieth century, the conceptual roots of computer technology date back to antiquity. Historians of information technology often point to the use of the abacus, the world’s oldest calculating tool, as being the computer’s original starting place. They believe that the Chinese, the Babylonians, and the Egyptians used various forms of the abacus as long ago as 3000 BC. It was the first implement in human history to be employed for mathematical computations.

Thousands of years later, in the late nineteenth century, humans moved one step closer to modern computer technology. In 1890, Herman Hollerith and James Powers invented a machine that could perform computations using punch card technology. Their machine was designed to speed up computations for the U.S. Census Bureau.

Punch card machines like this became the computing workhorses of the business and scientific world for half a century. The outbreak of World War II, however, hastened the development of the modern computer, when machines were urgently needed that could swiftly perform complex calculations. Several competing versions were developed. While there is some debate over which machine was the world’s first all electronic computer, the majority of historians believe the honor should go to the ENIAC (Electronic Numeric Integrator and Computer). This electronic wonder was completed in 1946 at the University of Pennsylvania. It could perform calculations about 1000 times faster than the previous generation of computers. (See Figure 2.1.)

Figure 2.1 The ENIAC, completed in 1946, is regarded as the world’s first high-speed electronic computer, but it was a hulking piece of equipment by today’s standards.

Photograph courtesy of IBM Corporate Archives.

Despite the ENIAC’s great speed, however, it did have some drawbacks. It was a cumbersome and bulky machine, weighing 30 tons, taking up 1800 square feet of floor space, and drawing upon 18,000 vacuum tubes to operate. Furthermore, though it was efficient at performing the tasks it had been designed to do, it could not be easily reprogrammed.

During the three decades following the building of the ENIAC, computer technology progressed in a series of rapid steps, resulting in computers that were smaller and faster, had more memory, and were capable of performing more functions. Concepts such as computer-controlled robots and artificial intelligence (AI) were also being articulated and refined. By the 1970s, computer technology developed to the point where the essential elements could be shrunk down in size to a tiny microchip, meaning that a great number of devices could be computer enhanced. As computer hardware became smaller and less expensive, personal computers (PCs) became widely available to the general public, and the use of computers accelerated rapidly through the 1970s and 1980s. It wasn’t long before computer technology permeated everything from children’s toys to supermarket scanners to household telephones.

THE BIRTH OF THE INTERNET

As important as the invention of the computer is, another technological achievement also played a critical role in the development of digital storytelling: the birth of the Internet. The basic concept that underlies the Internet—that of connecting computers together to allow them to send information back and forth even though they are geographically distant from one another—was first sketched out by researchers in the 1960s. This was the time of the cold war, and such a system, it was believed, would help facilitate the work of military personnel and scientists who were working on defense projects at widely scattered institutions. The idea took concrete shape in 1969 when the U.S. Department of Defense commissioned and launched the Advanced Research Project Agency Net, generally known as ARPANET.

Although originally designed to transmit scientific and military data, people with access to ARPANET quickly discovered they could also use it as a communications medium, and thus electronic mail (email) was born. And in 1978 there was an even more important discovery from the point of view of digital storytelling: Some students in England realized that electronic networks could be harnessed as a medium of entertainment, inventing the world’s first text-based role-playing adventure game for it. The game was a MUD (Multi-User Dungeon or Multi-User Domain or Multi-User Dimension), the forerunner of today’s enormously popular Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs).

In 1982, Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn designed a new protocol for ARPANET. A protocol is a format for transmitting data between two devices, and theirs was called TCP/IP, or Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol. Without it, the Internet could not have grown into the immense international mass-communication system it has become. The creation of TCP/IP is so significant that it can be regarded as the birth of the Internet.

In 1990, the Department of Defense decommissioned ARPANET, leaving the Internet in its place. And by now, the word “cyberspace” was frequently being sprinkled into sophisticated conversations. William Gibson first coined the word in 1984 in his sci-fi novel, Neuromancer, using it to refer to the nonphysical world created by computer communications. The rapid acceptance of the word “cyberspace” into popular vocabulary was just one indication of how thoroughly electronic communications had managed to permeate everyday life.

Just one year after ARPANET was decommissioned, the World Wide Web was born, created by Englishman Tim Berners-Lee. Berners-Lee recognized the need for a simple and universal way of disseminating information over the Internet, and in his efforts to design such a system, he developed the critical ingredients of the Web, including URLs, HTML, and HTTP. This paved the way for new forms of storytelling and games on the Internet. The Internet’s popularity has continued to zoom upward all over the globe, reaching a total of 747 million users in 2007.

THE FIRST VIDEO GAMES

Just as the first online game was devised long before the Internet was an established medium, the first video games were created years before personal computers became commonplace. They emerged during the era when computer technology was still very much the domain of research scientists, professors, and a handful of graduate students.

THE WORLD’S FIRST VIDEO GAME

Credit for devising the first video game usually goes to a physicist named Willy Higinbotham, who created his game in 1958 while working at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York. His creation, Tennis for Two, was, as its name suggests, an interactive ball game, and two opponents would square off to play it. In an account written over 20 years later and posted on a U.S. Department of Energy website (www.osti.gov), Higinbotham modestly explained that he had invented the game to have something interesting to put on display for his lab’s annual visitor’s day event. The game was controlled by knobs and buttons and ran on an analog computer. The graphics were displayed on a primitive-looking oscilloscope, a device normally used for producing visual displays of electrical signals. It was hardly the sort of machine one would associate with computer games. Nonetheless, the game was a great success. Higinbotham’s achievement is a vivid illustration of human ingenuity when it comes to using the tools at hand.

A game called Spacewar, although not the first video game ever created, was the most direct antecedent of today’s commercial video games. Spacewar was created in the early 1960s by an MIT student named Steve Russell. Russell, working with a team of fellow students, designed the game on a mainframe computer. The two-player game featured a duel between two primitive-looking spaceships, one shaped like a needle and the other like a wedge. It quickly caught the attention of students at other universities and was destined to be the inspiration of the world’s first arcade game, though that was still some 10 years off.

In the meantime, work was going forward on the world’s first home console games. The idea for making a home console game belongs to Ralph Baer, who came up with the revolutionary idea of playing interactive games on a TV screen way back in 1951. At the time, he was employed by a television company called Loral, and nobody would take his idea seriously. It took him almost 20 years before he found a company that would license his concept for a console, but finally, in 1970, Magnavox stepped up to the plate. The console, called the Magnavox Odyssey, was released in 1972, along with 12 games. The console demonstrated the feasibility of home video games and paved the way for further developments in this area.

At just about the same time as the console’s release, things were moving forward in the development of arcade games. Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, the future founders of Atari, created an arcade version of Spacewar, the game that had been made at MIT, and released it in 1971. Their game, Computer Space, was the first arcade game ever, but it was a failure, reportedly because people found it too hard to play. Dabney lost faith in the computer game business and he and Bushnell parted company. Bushnell, however, was undaunted. He went on to produce an arcade game called Pong, an interactive version of ping-pong, complete with a ponging sound when the ball hit the paddle. Released in 1972, the game became a huge success. In 1975, Atari released a home console version of the game, and it too was a hit.

Pong helped generate an enormous wave of excitement about video games. A flurry of arcade games followed on its heels, and video arcade parlors seemed to spring up on every corner. By 1981, less than 10 years after Pong was released, over 1.5 million coin-operated arcade games were in operation in the United States, generating millions of dollars.

During the ensuing decades, home console games similarly took off. Competing brands of consoles, with ever more advanced features, waged war on each other. Games designed to take advantage of the new features came on the market in steady numbers. Of course, console games and arcade games were not the only form of interactive gaming in town. Video games for desktop computers, both for the PC and Mac, were also being produced. These games were snapped up by gamers who were eager for exciting new products.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF OTHER IMPORTANT INTERACTIVE PLATFORMS

Not counting the great variety of video game consoles, four other significant platforms were introduced during the 20 years between the late 1970s and the late 1990s. All of these technologies—laser discs, CD-ROMs, CD-is, and DVDs—were used as vehicles for interactive narratives, some more successfully than others.

Laser Discs

Laser discs, also called video discs, were invented by Philips Electronics and made available to the public in the late 1970s. The format offered outstandingly clear audio and video and was easy to use. Consumers primarily used laser discs for watching movies, while its interactive capabilities were more thoroughly utilized in educational and corporate settings.

The laser disc’s potential as a vehicle for pure interactive fun came into full bloom in the arcade game Dragon’s Lair, released in 1983. The game not only fully exploited the capabilities of laser disc technology but also broke important new ground for video games. Unlike the primitive graphics of other games up until then, Dragon’s Lair contained 22 minutes of vivid animation. It also had a far more developed storyline than the typical “point and shoot” arcade offerings. As a player, you had the heady experience of “becoming” the hero of the story, the knight Dirk the Daring, and as Dirk, you had a dangerous mission to fulfill: to rescue Princess Daphne from a castle full of monsters. The game was an entertainment phenomenon unlike anything seen to date. So many people wanted to play it that arcade machines actually broke down from overuse.

CD-ROMS

CD-ROMs (for Compact Disc-Read Only Memory) were introduced to the public in 1985, a joint effort of Philips and Sony, with prototypes dating back to 1983. These little discs could store a massive amount of digital data—text, audio, video, and animation—which could then be read by a personal computer. Prior to this, storage media for computer games—floppy discs and hard discs—were far more restrictive in terms of capacity and allowed for extremely limited use of moving graphics and audio.

In the early 1990s, the software industry began to perceive the value of the CD-ROM format for games and edutainment (a blend of education and entertainment). Suddenly, these discs became the hot platform of the day, a boom period that lasted about five years. Myst and The Seventh Guest were two extremely popular games that were introduced on CD-ROMs, both debuting in the early 1990s. It also proved to be an enormously successful format for children’s educational games, including hits like the Carmen Sandiego and Putt-Putt series, Freddie Fish, MathBlaster, The Oregon Trail, and the JumpStart line.

The success of the CD-ROM as a platform for games was largely due to its ability to combine story elements with audio and moving visuals (both video and animation). Even professionals in Hollywood started to pay attention, intrigued with its possibilities, and hoping, as one entrepreneur put it back then, “to strike gold in cyberspace.”

Unfortunately, CD-ROMs went through a major downturn in the second half of the 1990s, caused in part by the newest competitor on the block, the Internet. Financial shake-ups, mergers, and downsizing within the software industry put the squeeze on the production of new titles, and many promising companies went out of business. Despite this painful shake-up, however, CD-ROMs have remained a major platform for delivering games, education, and even corporate training, along with DVDs and the Internet.

CD-is

The CD-i (Compact Disc-interactive) system was developed jointly by Philips and Sony and was introduced by Philips in 1991. Termed a “multimedia” system, it was intended to handle all types of interactive genres, and it was the first interactive technology geared for a mass audience. The CD-i discs were played on special devices designed for the purpose and connected to a TV set or color monitor. The system offered high quality audio and video and was extremely easy to use.

Although CD-ROMs were already out on the market at the time CD-is came along, the new platform helped spur significant creative advances in interactive entertainment, in part because Philips was committed to developing attractive titles to play on its new system. Among them was Voyeur, a widely heralded interactive movie–game hybrid.

DVDs

DVD technology was introduced to the public in 1997, developed by a consortium of 10 corporations. This group, made up of major electronics firms, computer companies, and entertainment studios, opted to pool their resources and work collaboratively, rather than to come out with competing products, a practice that had led to the demise of prior consumer electronics products. In a few short years, the DVD became the most swiftly adopted consumer electronics platform of all time.

The initials DVD once stood for “Digital Video Disc,” but because the format could do so much more than store video, the name was changed to Digital Versatile Disc. The second name never caught on, however, and now the initials themselves are the name of the technology.

DVD technology is extremely robust and versatile. The quality of the audio and video is excellent, and it has a far greater storage capacity than either CD-ROMs or laser discs. While primarily used to play movies or compilations of television shows, it is also used as a platform for original material, including interactive dramas and documentaries. (For more on DVDs, please see Chapter 23.)

Less Familiar Forms of Interactive Entertainment

As we will see in future chapters of this book, a number of other important technologies and devices are employed for digital storytelling, and new ones are introduced on a frequent basis. Some platforms for interactive narrative are extremely familiar to the general public and are highly popular—such as video game consoles and the Internet—while others, such as interactive television, have been slower to catch on. We will be exploring both the highly popular forms and the less familiar forms throughout this book.

THE EVOLUTION OF CONTENT FOR A NEW MEDIUM

As we have seen, digital storytelling is an extremely new form of narrative, and it has only had a very brief period of time to develop. The first years of any new medium are apt to be a rocky time, marked by much trial and error. The initial experiments in a new field don’t always succeed, and significant achievements are sometimes ignored or even ridiculed when first introduced.

THE EARLY DAYS OF A NEW MEDIUM

The very first works produced for a new medium are sometimes referred to as incunabula, which comes from the Latin word for cradle or swaddling clothes, and thus means something still in its infancy. The term was first applied to the earliest printed books, those made before 1501. But now the term is used more broadly to apply to the early forms of any new medium, including works made for various types of digital technology.

When creating a work for a brand new medium, it is extremely difficult to see its potential. People in this position must go through a steep learning curve to discover its unique properties and determine how they can be used for narrative purposes. To make things even more challenging, a new technology often has certain limitations, and these must be understood and ways must be found to cope with them. Creating works for a new medium is thus a process of discovery and a great test of the imagination.

Typically, projects created for a new medium go through an evolution, with three major steps:

1. The first step is almost always repurposing, which is the porting over materials or models from older media or models, often with almost no change. For instance, many early movies were just filmed stage plays, while in digital media, the first DVDs just contained movies and compilations of TV shows, and many of the first CD-ROMs were digital versions of already existing encyclopedias.

2. The middle step is often the adaptation approach, or a spin-off. In other words, an established property, like a novel, is modified somewhat for a new medium, like a movie. Producers of TV series have been taking this approach with the Internet by creating webisodes (serialized stories for the Web) and mobisodes (serialized stories for the mobile devices) based on successful TV shows.

3. The final and most sophisticated step is the creation of totally original content that makes good use of what the new medium has to offer and does not imitate older forms. For example, the three-camera situation comedy is a unique genre that takes full advantage of the medium of television. The same can be said of the MMOG, which takes full advantage of the opportunities offered by the Internet.

Developing works for digital media has presented challenges never faced before by the creative community. For example, how could you tell a story using interactivity and a nonlinear structure? And how would the user be made aware of the interactivity and know how to use it?

THE PROFOUND IMPACT OF DIGITAL MEDIA

Since the days when it was first called ARPANET, the Internet has matured as a major medium of distribution. A critical mass of users now has broadband connectivity, making it possible to receive and send large quantities of audio and video. Users can download and watch episodes of TV series on their computers and even watch entire feature length movies, not to mention the wealth of shorter pieces of video and animation that are so abundant on the Internet. Broadband has also helped to turn the Internet into a robust vehicle for original content of all types, including new genres of games, new forms of drama, and new types of journalism. Broadband has also made it possible to create whole new types of social communities, such as virtual worlds, social networking sites, and video file sharing sites.

The maturing of the Internet is just one reason for this digital revolution. Another important factor is the creation of new digital devices that make it possible to watch and listen to programming no matter where you are. Apple has been an important innovator in this area. It built the iTunes website, which allowed users to download music for a small fee, and also created the iPod, a conveniently portable and stylish piece of playback equipment for listening to your downloaded music and other kinds of audio programming. Then, in 2005, Apple introduced the video iPod, enabling users to download video as well as audio content from the Internet.

When Apple released the video iPod, it also announced that it would make episodes of hit television shows available on its iTunes website for a small fee. Within the first year, it sold 45 million TV shows. In addition, the iPod can be used to watch full-length movies and play simple video games. It can also be used to watch or listen to podcasts (Internet audio and video broadcasts that can be watched online or downloaded to mobile devices). The iPod is probably the best-known portable media device, but sophisticated cell phones and other types of mobile devices can also be used to enjoy all kinds of audio and video content, as can many types of video game consoles.

Another device that has played a role in the digital revolution is the personal video recorder (PVR), also known as the digital video recorder (DVR). This type of device, of which TiVo is the best known, allows TV viewers to select and record TV programs and play them back whenever they wish. Viewers also have the option of fast forwarding through the commercials, a feature that many appreciate. And viewers who own a piece of equipment called the Sling can even send recorded programming to their computers, no matter where their computers happen to be. Let’s say, for example, your TiVo is in your apartment in Manhattan, but you are on a business trip to Paris. With a Slingbox, you could forward your TV favorite show to your laptop in your Paris hotel room.

TiVos, PVRs, iPods, and other digital devices have freed television viewers from the tyranny of the television schedule. As one media analyst put it, “Appointment- based television is dead.” Perhaps this is an overstatement, but there’s no question that developments in recent years—including the development of the Internet as major new medium, new forms of digital distribution, and the enormous popularity of video games and other kinds of digital entertainment—are having a profound impact on the Hollywood entertainment establishment. This digital revolution is also having a number of other ramifications. For example, it is impacting how and where advertising dollars are spent, and it is profoundly changing the world of journalism. It is also bringing about innovations in the way students are taught and how employees are trained. And, most relevant to this book, it is sparking the creation of exciting new forms of storytelling.

Changes in the Consumption of Entertainment

From the debut of the world’s first commercial video game, Pong, in 1972 to the present day explosion of digital content, the popularity of digital entertainment has grown at a steady and impressive rate. Not only are more people consuming digital entertainment, but they are also spending more hours enjoying it. As a result, the audiences for traditional forms of entertainment have shrunk. We are now at the point where digital content can no longer be considered a maverick outsider because it has become an accepted part of the mainstream entertainment world.

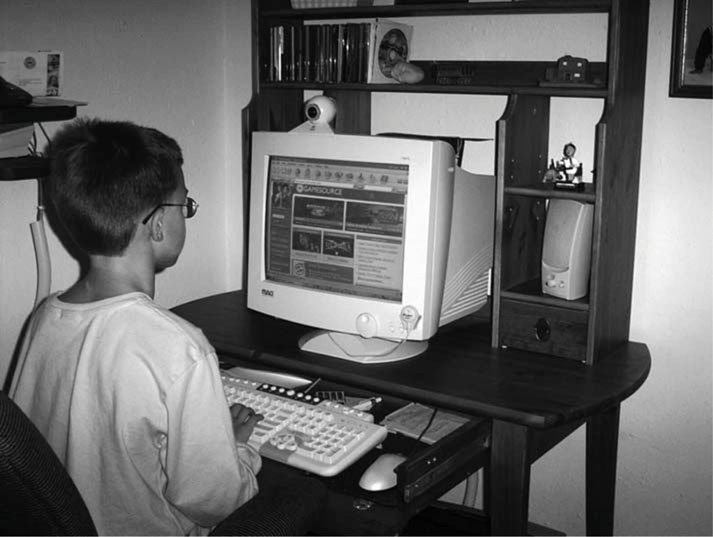

Young people, in particular, are enormous fans of digital entertainment and everything digital. (See Figure 2.2.) They text message each other on their cell phones, instant message (IM) each other and watch streaming video on the Internet, listen to music on their iPods, and play games on their game consoles. A 2007 study released by JupiterResearch reported that people between the ages of 18 and 24 spend twice as much time online as they do watching television.

Figure 2.2 Young people are great fans of all types of digital media, and as their use of interactive platforms increases, the time they spend consuming television and movies declines.

Older people are also spending more time on pursuits typically considered the domain of teenaged boys. According to statistics released in 2007 by the Entertainment Software Association (ESA), the average age of gamers has risen to 33, and a full 25% of players are over 50. Furthermore, girls and women now make up 38% of the gamer population.

Digital media is having a major impact on broadcast television, which is slowly being overshadowed by the penetration of broadband Internet access. According to The Hollywood Reporter, for example, more homes in the United States have broadband access than subscribe to HBO.

While once there were only two entertainment screens that mattered—TV screens and movie screens—there is now a powerful “third screen” to contend with. This so-called third screen is really composed of multiple types of screens, a mixture of game consoles, computer monitors, and other digital devices.

The Impact on Hollywood

Television networks and movie studios are by no means unaware of the digital revolution, and the most forward-looking of them are taking steps to minimize the negative impact and to even take advantage of it as much as possible. They clearly want to avoid being blindsided the way the music industry was in the late 1990s with illegal file sharing. Until the courts put an end to it, people were able to download songs for free, using Napster’s file sharing services. This online piracy caused the recording industry to suffer tremendous financial losses, and now that video can easily be downloaded from the Internet, Hollywood is taking steps to avoid a similar debacle.

Thus, following Apple’s lead, a number of film studios and TV networks have been making their movies and TV shows readily available for legal downloads for a small fee. Some are also adapting an innovative multiplatforming strategy. With multiplatforming, not only do they create entertainment content for their two traditional screens—movie theatres and TV sets—but they also create auxiliary content for the third screen. When the same narrative storyline is developed across several forms of media, one of which is an interactive medium, it is known as transmedia entertainment.

Content created for a multiple media approach may take the form of dramatic material such as webisodes and faux blogs (blogs that are written in the voice of fictional characters, much like diaries). They may also use digital media to involve viewers in a mystery that’s part of the plot of a TV show, giving them clues on websites and other venues so they can help solve it. Or sometimes, especially with television shows, the producers will find ways to involve the viewers while the show is being broadcast. For example, viewers may use their cell phones or laptops to participate in contests or polls, vote a contestant off a reality show, or voice an opinion.

The multiplatforming and transmedia approach to content is being used across the spectrum of television programming, including sitcoms, reality shows, dramas, news shows and documentaries. These strategies serve multiple purposes. They

• make the shows more attractive to younger viewers—the demographic that is particularly fond of interactive entertainment;

• keep viewers interested in a show and involved with it even when it is not on the air, in the days between its regular weekly broadcast, and during the summer hiatus;

• attract new viewers to a show;

• take advantage of new revenue streams offered by video on demand (VOD), the Internet, and mobile devices.

These techniques are equally important in the feature film arena, although here digital platforms are primarily used for promotional purposes. We will be exploring the multiplatforming and transmedia approach to storytelling, and the kinds of interactive content that grow out of it, throughout this book, with Chapters 9 and 17 specifically devoted to this topic.

Despite various efforts to embrace the digital revolution, it is clear that traditional Hollywood entertainment is taking a hit from the third screen. Not only is television viewing down, but movie attendance is also being impacted. According to The New York Times (December 11, 2005), people are getting pickier about the types of films they go to. The big event movies remain popular, as do the specialized low-budget genre pictures, but the films that are middle-of-the-road, with midlevel budgets, are doing poorly. It indicates that while people may be willing to spend money to go to films they really want to see, they’d rather stay home and watch a DVD or play a video game than go to movies that don’t sound particularly appealing.

THE IMPACT ON HOLLYWOOD’S TALENT POOL

The popularity of digital media is also rocking the boat with Hollywood professionals. Writers, actors, and directors are demanding that they be paid fairly when their work is downloaded from the Internet or when they contribute to a new form of content like a webisode. The long-established compensation system for top talent was created well before the digital revolution and doesn’t cover these situations. Not surprisingly, payment issues have grown contentious. As of this writing they have already led to a major strike by the Writers Guild of America, the union that represents Hollywood writers. Digital technology is raising some unexpected concerns, as well. For example, actors worry that their voices and images may be digitized and used in productions without their consent, meaning that they could lose jobs to a virtual version of themselves.

How Advertisers Are Responding

People inside the world of the Hollywood entertainment business are not the only ones grappling with the sea changes created by the explosion of digital media. These changes are also creating upheavals for the advertising industry. In the past, television commercials were a favored way of promoting products, and advertisers spent a staggering amount of money on them—approximately $250 billion in 2005 alone. But they are becoming far less willing to make such an investment under the present circumstances. Not only is television viewing down, but people are also downloading commercial-free shows from the Internet, fast-forwarding through commercials on their PVRs, and viewing commercial-free television programming on DVDs. Another major medium for advertising—the daily newspaper—is also becoming less attractive to advertisers. Circulation numbers are plummeting almost everywhere, and readership is especially low with young people, who prefer to get their news online or through their mobile devices.

Thus, advertisers are shifting their ad dollars to other areas. An ever-larger portion is going to the Internet. In 2007, online advertising rose 34% above the previous year, reaching a total of almost $17 billion. Advertisers are also investing in product placement in video games. In a car racing game, for example, the track might be plastered with billboards promoting a particular product, or in a sports game, the athletes may be wearing shirts emblazoned with the name of a clothing line. In 2006, $80 million was spent on in-game advertising.

Even the way advertising is done on broadcast TV is changing somewhat. There are more infomercials—full-length shows that promote a particular product— and more sponsored programs, which are entertainment shows that are fully funded by a single advertiser, in other words, shows that are “brought to you” by a particular product. And the kind of product placement found in games is also on the rise in television and movies.

In addition, advertisers are devising new forms of digital narratives and games to promote products, which is of particular interest to those of us involved in digital storytelling. For example, they are putting money into advergaming—a form of casual gaming that integrates a product into the game and is often set in a narrative frame. They are also producing webisodes and elaborate multiplatform games that subtly or not so subtly make a particular product shine. We will be exploring these new types of content throughout this book.

The Impact of Digital Media on the Economy

Along with shifts in the way that advertising dollars are being spent, the digital revolution is impacting other areas of the economy, often in quite positive ways. For example, video games are an extremely healthy growth industry. Worldwide, games earned an impressive $31.6 billion in 2006, a figure that was expected to rise to $37.7 billion by the end of 2007, according to The Hollywood Reporter (June 21, 2007). And, according to the gaming industry, video games now gross more money than ticket sales for feature films.

In 2006, the Entertainment Software Association released a report focusing on the economic impact of video games, Video Games: Serious Business for America’s Economy. According to the report, games were responsible for creating 144,000 full-time jobs. Many of these jobs are high paying; recent college graduates employed by game companies earn significantly more money than the average college graduate. In addition, the report noted that software developed for games is being applied to other endeavors. For example, gaming software had been adapted by the real estate market and the travel industry, which uses it for virtual online tours. Video game techniques have been successfully incorporated into educational and training games used by schools, corporations, and the military.

The Impact on Journalism and How We Receive Information

The digital revolution has both hurt and helped the field of journalism, and it has profoundly impacted the way information is disseminated. While newspaper circulation is down, as is the viewership of television newscasts, we have a whole universe of new sources of information and journalism, thanks to digital media. On the Internet, we can receive up-to-the-minute news stories, complete with audio and video, and we also get information from blogs, interactive informational websites, online news magazines, and podcasts. And via our mobile devices, we can receive news bulletins, check stock prices, get weather reports, and keep tabs on sports events.

To get an idea of how important these digital news sources have become, one need look no further than the 2008 campaign for the presidency of the United States, which as of this writing is still ongoing. Candidates for this high stakes election have made intensive use of digital media. They’ve announced their candidacy on YouTube, set up websites, written blogs, and created profiles for Facebook and MySpace. They, or their advisors, are obviously aware of the power of digital media, and their use of it carries a subtext, as well. Candidates who make use of digital media are proclaiming: “I’m with it; I’m plugged in to modern times; I’m not some old fuddy duddy dinosaur.”

WHAT THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION MEANS FOR CONTENT

As we have seen, digital technology has had a colossal impact on content, giving us many new forms of entertainment and new ways to receive information. In recent years, it has also given us a powerful new vehicle for content delivery— broadband Internet service. Broadband has helped to turn the Internet into a robust vehicle for original storytelling of all types, including new genres of games like Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs), Alternate Reality Games (ARGs), and episodic mystery games. It has spawned new forms of drama, as we have already noted, such as webisodes and fictional blogs, and new types of storytelling for children.

In addition, broadband has facilitated the development of sites dominated by user-generated content, such as virtual worlds and video sharing sites. Furthermore, digital technology is providing creative individuals in the fine arts with new ways to express themselves.

Types of User-Generated Content

Unlike other types of digital entertainment, the material found on sites that support user-generated content is largely created by the users themselves. Such websites are enormously popular and are one of the fastest growing areas of the Internet. These online destinations can roughly be divided into four general genres: virtual worlds; sites featuring users’ profiles; sites featuring users’ videos and animations; and sites featuring fan fiction. In addition to these, there is another important type of user-generated content, Machinima, that is not primarily an online form.

VIRTUAL WORLDS

Virtual worlds are online environments where users control their own avatars and interact with each other. These worlds may have richly detailed landscapes to explore, buildings that can be entered, and vehicles that can be operated, much like a MMOG. However, these virtual worlds are not really games, even though they may have some gamelike attributes. Instead, they serve as virtual community centers, where people can get together and socialize and, if they wish, conduct business.

Second Life is the most successful of these virtual worlds. By mid-2007, it had almost eight million “residents,” as users are called. Second Life is a complex environment, offering different types of experiences to different residents, much like real life. It is a thriving center of commerce, for instance, where residents can buy and sell real estate, crafts, and other goods. People who like to party can fill their social calendar with all kinds of lively events. But Second Life can also be a place of higher learning. Real universities, including Harvard and Pepperdine, conduct classes there. In addition, real corporations hold shareholder meetings there, and politicians set up campaign headquarters there. It can also be a romantic destination. Residents have met in Second Life, fallen in love, and gotten married in real life.

VIRTUAL WORLDS FOR THE KIDS

While Second Life is intended for grown-ups, children need not feel left out of the chance to enjoy virtual worlds. Software developers have created a host of virtual worlds just for them. For example, capitalizing on the popular craze for penguins, New Horizon Interactive created a virtual world called Club Penguin in 2005 for children aged 6 to 14. Kids get to control their own penguin avatars and play in a wintery-white virtual world. Another site called WeeWorld lets small children control avatars, called WeeMees, play games, and send messages to each other. Even the famous Barbie (otherwise known as Barbie Doll) has joined this rush to create virtual worlds. She has developed a site for girls, BarbieGirls, where girls create their own Barbie girl avatars.

SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES

Social networking sites primarily feature users’ profiles, making them quite different from virtual worlds. Two of the most popular of these social sites are MySpace and Facebook. Along with personal profiles, they contain photos, videos and users’ blogs. Although these two sites have somewhat different features, they both are designed to facilitate socializing. They are two of the most frequently visited sites on the Internet.

VIDEO SHARING SITES

Some websites primarily serve as online spaces where users can share their own creative works, primarily videos and animation. YouTube is the best known and most successful of these. Created in 2005, it has become an enormously popular place for people to upload their own videos and view videos made by others. While much of the content is made by nonprofessionals, it also hosts slickly made commercial material. And, as noted earlier, politicians sometimes use YouTube to try to woo prospective voters.

FAN FICTION

Fan fiction, also known as fanfic, is a type of narrative that is based on a printed or produced story or drama, but it is written by fans instead of by the original author. Works of fan fiction may continue the plot that was established in the original story, may focus on a particular character, or may use the general setting as a springboard for a new work of fiction. This genre of writing began long before the advent of digital media. Some experts believe it dates back to the seventeenth century, beginning with sequels of the novel Don Quixote that were not written by Cervantes himself but by his admirers. Since then, other popular novels have been used as launching pads for fan fiction. In the twentieth century, until the birth of the Internet, this type of writing primarily revolved around the science fiction TV series Star Trek. With the Internet, however, fan fiction has found a welcoming home and a wider audience. Sites for this type of user-generated content abound, with fans creating stories for everything from Harry Potter novels to Japanese anime.

MACHINIMA

Machinima, a term that combines the words “machine” and “cinema,” is a form of filmmaking that borrows technology, scenery, and characters from video games but creates original stories with them. Though it is a form of user-generated content, it is not, as noted, an Internet-based form, though works of Machinima can be found on the Web.

The best known Machinima production is Red vs Blue, a multiepisode tongue-in-cheek science fiction story about futuristic soldiers who have strange encounters in a place called Blood Gulch. Works of Machinima are often humorous, possibly because the characters, borrowed as they are from video games, are not capable of deep expression. Film connoisseurs are beginning to regard Machinima as a genuine and innovative form of filmmaking. A group of these films were shown at Lincoln Center in New York City, where they were described as “absurdist sketch comedy.” Machinima has even found a foothold in the documentary film community, where it has been used to recreate historic battle scenes.

Thus, as demonstrated by these very different types of user-generated content, digital tools can give “regular people” the opportunity to do things that may be difficult to do outside of cyberspace—the opportunity to socialize, express themselves, be creative, and share their creations.

Digital Technology and the Arts

It should be stressed that amateurs are not the only ones to use digital tools. Professionals in the fine arts are also using them. Although they are, for the most part, outside of the scope of this book, innovative works using computer technology are being made in the fields of visual arts, music, performing arts, poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction. For lack of a better term, these works are often labeled as “new media art.”

In some cases, these works can be found in mainstream environments. Just as one example, in 2007 the London Philharmonic performed a virtual reality version of Igor Stravinsky’s ballet Le Sacre du Printemps at the newly refurbished Royal Festival Hall in London. Using Stravinsky’s music as a springboard, media artist and composer Klaus Obermaier designed a piece in which dancer Julia Mach interacted with the music and the three-dimensional images projected onto the stage. Members of the audience watched the performance wearing 3-D glasses.

In the area of visual arts, several major museums, such as the Metropolitan Museum and Whitney Museum in New York City, contain new media art works in their collections, and in some cases museums have held exhibits that heavily feature such works. For instance, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles held an exhibition in 2005 called Visual Art, which contained a number of new media art pieces. The exhibit explored the relationship between color, sound, and abstraction.

For the most part, however, artists who work in new media are still struggling to find an audience, and most of them support themselves by teaching at universities. This is also the case of writers who work in digital literature. This type of writing is sometimes called hyperliterature, a catchall phrase that includes hypertext, digital poetry, nonlinear literature, electronic literature, and cyberliterature. Several websites specialize in this kind of writing, including the Hyperliterature Exchange and Eastgate, a company that publishes hypertext. In addition, the Electronic Literature Organization promotes the creation of electronic literature. A particularly lovely example of this kind of work is the hyperliterature version of the Wallace Stevens poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” which was recreated as short Flash animation pieces by British artist–writer Edward Picot.

Unfortunately, there is not sufficient room in this book to delve deeply into the realm of fine arts. However, we will be exploring a number of works that fall into the category of fine arts, particularly in the fields of interactive cinema and immersive environments.

A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

Although many of the developments mentioned in this chapter, as well as many of the statistics cited, refer specifically to the United States, it is important to keep in mind that digital entertainment is popular throughout the world and that software production centers are also scattered worldwide. The United States does not have the same stranglehold on digital media as it does on the television and motion picture industry, and it even lags behind other developed countries in some forms of digital technology, such as high-speed Internet access. Countries from India to South Africa to Australia are creating innovative content for digital media and devices, with especially strong production centers in Japan, South Korea, Germany, Great Britain, and Canada.

Furthermore, some forms of digital technology and entertainment are better established outside of the United States than within its borders. Cell phones and content for them are tremendously successful in Japan; video games flourish in Korea; interactive television is well established in Great Britain; and Scandinavian countries lead the way in innovative transmedia games.

CONCLUSION

Clearly, digital storytelling is no longer the niche activity it was several decades ago. While once barely known outside of a few research labs and academic institutions, it can now boast of a worldwide presence and a consumer base numbering in the millions. It can be enjoyed in homes, schools, offices, and via wireless devices virtually anywhere. Furthermore, it is also no longer just the domain of teenage boys. Its appeal has broadened to include a much wider spectrum of the population, in terms of age, gender, and interest groups. It is powerful and universal enough to become a serious contender for the public’s leisure time dollars and leisure time hours, and it is muscular enough to cause consternation in Hollywood.

A striking number of the breakthroughs that have paved the way for digital storytelling have come from unlikely places, such as military organizations and the laboratories of scientists. Thus, we should not be surprised if future advances also come from outside the ranks of the usual suppliers of entertainment content.

Various studies have documented the enthusiasm young people have for interactive media. This demographic group has been pushing interactive entertainment forward much like makers of snowmen roll a ball of snow, causing it to expand in size. Almost inevitably, as members of this segment of the population grow older, they will continue to expect their entertainment to be interactive. But will the same kinds of interactive programming continue to appeal to them as they move through the various stages of life? And how can emerging technologies best be utilized to build new and engaging forms of interactive entertainment that will appeal to large groups of users? These are just two of the questions that creators in this field will need to address in coming years.

IDEA-GENERATING EXERCISES

1. Try to imagine yourself going through a normal day but as if the calendar had been set back 50 years, before computers became commonplace. What familiar devices would no longer be available to you? What everyday tasks would you no longer be able to perform or would have to be performed in a quite different way?

2. Imagine for a moment that you had just been given the assignment of creating a work of entertainment for a brand new interactive platform, one that had never been used for an entertainment purpose before. What kinds of questions would you want to get answers to before you would begin? What steps do you think would be helpful to take as you embarked on such a project?

3. Most children and teenagers in developed countries are major consumers of interactive entertainment, but what kinds of interactive projects do you think could be developed for them as they move into adulthood, middle age, and beyond? What factors would need to be considered when developing content for this group as they mature?

4. Analyze a website that facilitates social networking or the sharing of user-generated material, if possible, not one described in this chapter. What demographic group is this site primarily geared for? What about the site should make it attractive to its target demographic? What are its primary features? Is there anything about this site that you think could be improved upon?