CHAPTER 9

Using a Transmedia Approach

How can you tell a story by tying the content together across multiple platforms?

Why is the transmedia approach so attractive from a creative person’s point of view?

How is the transmedia approach being used for nonfiction endeavors like documentaries and reality-based projects?

Why is Hollywood taking such a keen interest in transmedia entertainment?

A DIFFERENT APPROACH TO STORYTELLING

Traditionally, narratives have been created for a single and specific medium—to be acted on the stage, for instance, or to be printed in a book or filmed for a movie. Sometimes a work might later be adapted into another medium, but such adaptations are rarely planned in advance; essentially, adaptations are just another way to tell the same story. Quite recently, however, content creators have begun to take a very different approach to storytelling. They have started to devise narratives that are designed from the ground up to “live” on several forms of media simultaneously. Each relates a different aspect of the story or relates it in a different manner. In this new approach, at least some of the story is offered on an interactive medium so that people can participate in it. This new type of storytelling, which we briefly discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, uses a transmedia approach to narrative.

The first transmedia production to catch the attention of the public was The Blair Witch Project, which was made in 1999. It consisted of just two components: a movie and website. The movie told the story of three young filmmakers who venture into the woods to make a documentary about a legendary witch and then vanish under terrifying circumstances, leaving behind their videotapes. The movie is constructed solely of the footage that is allegedly discovered after their disappearance, and it is presented as a factual documentary.

The website focused on the same central narrative idea that was developed in the film. At the time of the movie’s release in 1999, plenty of other websites had already been tied into movies. But what made The Blair Witch Project so remarkable, and what created such a sensation, was the way the website enhanced and magnified the “documentary” content of the film. It bore no resemblance to the typical promotion site for a movie, with the usual bios of the actors and director and behind-the-scenes photos taken on the set. In fact, it contained nothing to indicate that The Blair Witch Project was a horror movie or that it was even a movie at all.

Instead, the material on the website treated the account of the filmmakers’ trip into the woods as if were absolute fact. It offered additional information about the events depicted in the movie, including things that happened before and after the three filmmakers ventured into the woods. Visitors to the site could view video interviews with the filmmakers’ relatives, townspeople, and law enforcement officers, or examine an abundance of “archival” material. Thus, they could construct their own version of the mystery surrounding the missing filmmakers. The content of the website was so realistic than many fans were convinced that everything depicted in The Blair Witch Project actually took place.

Of course, the website was, in fact, just an extremely clever and inexpensive way to promote the low-budget movie. It accomplished this goal supremely well, and it created such intense interest and curiosity that The Blair Witch Project became an instant hit. Though simple by today’s transmedia productions, made up of just a movie and a website, it dramatically illustrated the synergistic power of using multiple platforms to expand a story. The website (www.blairwitch.com) has become an Internet classic and remains popular even now, though not all of its features are still functioning.

DEFINING THE TRANSMEDIA APPROACH

Transmedia storytelling is still so new that it goes by many different names. Some call it multiplatforming or cross-media producing. It is known to others as “networked entertainment” or “integrated media.” When used for a project with a strong story component, it may be called a “distributed narrative.” Gaming projects that use the transmedia approach may be called “pervasive gaming” or sometimes “trans-media gaming.” When this kind of gaming blurs reality and fiction, it is often called “Alternative Reality Gaming” or an “ARG.” The term “transmedia entertainment” seems to be gaining the most favor, however, and this is the term we are using here.

In any case, no matter what terminology is employed, these works adhere to the same basic principles:

• The project in question exists over more than a single medium.

• It is at least partially interactive.

• The different components are used to expand the core material.

• The components are closely integrated.

Transmedia productions must combine at least two media, though most utilize more than that. The linear components may be a movie, a TV show, a newspaper ad, a novel, or even a billboard. The interactive elements may be content for the Web, a video game, wireless communications, or a DVD. In addition, these projects may also utilize everyday communications tools like faxes, voice mail, and instant messaging. Some of these projects also include the staging of live events. The choice of platforms is totally up to the development team; no fixed set of components exists for these projects. Any platform or medium that the creators can put to good use is perfectly acceptable in these ventures.

AN INTERNATIONAL PHENOMENON

The use of the transmedia approach is spreading throughout the world. In South Africa, for example, the reality show Big Brother Africa was designed from the ground up to span a variety of media, as was the Danish music video show Boogie. From Finland and Sweden we can find a cluster of clever transmedia games centered on mobile devices. Great Britain is by no means being left in the dust here, particularly thanks to the BBC’s mandate that all its programs include an interactive element. Thus, the BBC is no longer thinking in terms of single-medium programming but is consistently taking a more property-centric approach. In addition, transmedia storytelling is being studied across the world, from MIT’s august program of Comparative Media Studies in North America to the University of Sydney in Australia.

To get the most from the transmedia approach, production companies that work in this area usually tackle such a project as a total package, as opposed to pasting enhancements onto a linear project. This is the philosophy that guides the South African firm Underdog, for example, which has helped develop the Big Brother Africa series. Underdog specializes in transmedia and is the leading producer of such projects on the African continent. Luiz DeBarros, Underdog’s creative director and executive producer, stressed the importance of considering the property as a whole instead of a single aspect of it. He said that at Underdog, they take the approach that a brand or property is separate from the platform. “In other words,” he explained, “we develop brands, not TV shows or websites, and we aim to make them work across a number of platforms. The brand dictates the platform, not the other way around.” DeBarros went on to give an excellent nutshell definition of the transmedia method of development, saying that it “is a property that has been created specifically to be exploited across several media in a cohesive and integrated manner.”

THE CREATIVE POTENTIAL OF TRANSMEDIA PRODUCTIONS

One reason that the transmedia approach is such a powerful storytelling technique is because it enables the user to become involved in the material in an extremely deep way and sometimes in a manner that eerily simulates a real-life experience. For instance, the user might receive phone calls, letters, or faxes from fictional characters in the story, or even engage in IM (instant message) sessions with them. By spanning a number of media, a project can become far richer, more detailed, and multifaceted.

It also offers the story creators an exceptional opportunity to develop extremely deep stories. Unlike television shows or a feature film, there is no time constraint on how long they can be. Some of these works utilize hundreds of fictional websites to spin out their narratives, including some that contain audio, animation, and video clips. It is not unusual for a full-length book to be commissioned as one of the media elements. And because these narratives can utilize virtually any communications medium in existence, they offer a tantalizing variety of ways to play out the story, limited only by the creators’ imaginations and by the budget.

While some of the motivation to create transmedia properties stems from promotional goals or the desire to build a more loyal audience for a TV show or a movie, commercial considerations are not necessarily the primary attraction for those who work on them. Many creative teams are drawn to this approach because of its untapped creative potential. In fact, I was fortunate enough to consult on such a project with my colleague Dr. Linda Seger. We were invited to assist with a highly innovative project from Denmark called E-daze, which was entirely original (not based on any existing property) and was self-funded by its three creators.

A contemporary story of love and friendship set against the turbulent background of the dot com industry, the E-daze story followed the same four characters across five interconnected media: the Web, a feature film, an interactive TV show, a novel, and a DVD. Each medium told the story from a somewhat different angle, and in its use of the website and the interactive TV show, E-daze found clever ways to involve the audience and to blur the lines between fiction and reality. Unfortunately, its creators were not able to secure the necessary financial backing to move it beyond the development stage, although it attracted considerable interest. Nevertheless, the E-daze project illustrated the unique ability of transmedia storytelling to import a rich dimensionality to a property and to tell a story in a deeper and more lifelike, immersive way than would be possible via a single medium. It is no wonder that many creators of such projects find the experience exhilarating despite the many complexities they inevitably engender.

GOING PRIME-TIME WITH TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING

Until fairly recently, content producers have been hesitant to undertake any expensive transmedia productions involving major forms of media, despite the great success of The Blair Witch Project. This is understandable, given that it is such a new and ambitious approach to storytelling. Thus, in the years immediately following The Blair Witch Project, the most interesting work being done in this arena was a new form of gaming, the Alternate Reality Game (ARG). This new genre intricately blends story and gaming elements together in a way that seems more like real life than fiction. The first of these works primarily centered around the Internet and were supported by a variety of adjunct communications components. Compared to a major motion picture or a television series, ARGs are relatively inexpensive to produce. (We will be discussing ARGs in Chapter 17.)

Then in the fall of 2002, a bold new kind of transmedia venture was introduced to the public. Entitled Push, Nevada, it combined both a story and a game, blurred fiction and reality, and used multiple media. Thus, it had all the characteristics of an ARG. Push, Nevada, however, was the first such project to use a prime-time TV drama as its fulcrum. The project was produced by LivePlanet, a company founded, in part, by Ben Affleck and Matt Damon, and the project had some of Hollywood’s most sophisticated talent behind it. With a first-class production team, network television backing, and over a million dollars in prize money, Push, Nevada was Hollywood’s first major step into transmedia waters.

The components that made up the Push, Nevada galaxy revolved around a quirky mystery that was devised to unfold in 13 60-minute television episodes on ABC. The unlikely hero of the story is an IRS investigator, Jim Prufrock, a clean-cut and earnest young man. One day, Prufrock receives a fax alerting him to an irregularity, possibly an embezzlement, in the finances of a casino in a town called Push, Nevada. He sets off to Push to investigate and becomes entangled in the strange goings on of this extremely peculiar town. The mostly unfriendly residents clearly have something—perhaps many things—to hide. An uneasy aura of corruption hangs over the town, and the tone of the television show is intriguingly off center, reminiscent of the old TV series Twin Peaks. With its complex plot, allusions to T.S. Eliot, and unresolved episode endings, the series was not the kind of TV fare that most viewers were used to.

The TV show, although obviously a critical element, was just one of several components employed to tell the story and support the game. Other elements included a number of faux websites, wireless applications, a book, and telephone messaging. During the preproduction process, great attention was paid to the development of both the story and the game, and to make sure all the elements worked together, LivePlanet created a document called an Integrated Media Bible. They also developed an Integrated Media Timeline, which showed the relationship between the various media as the story and game played out over a number of weeks. (See Figure 9.1.)

Figure 9.1 A portion of the Integrated Media Timeline developed by LivePlanet for Push, Nevada to keep track of how the story and game unfolded across multiple platforms.

Image courtesy of LivePlanet.

WADING, SWIMMING AND DIVING

Just before the first episode of Push, Nevada aired, LivePlanet’s CEO, Larry Tanz, gave a presentation about the new venture to a group of industry professionals at the American Film Institute. In his talk, he described the project as “a treasure hunt for waders, swimmers, and divers.” In other words, members of the audience could determine the degree of involvement they wished to have. Some might only want to “wade” into its fictional world, which they could do just by watching the TV show. Others might choose to “swim” and sample parts of the story on other media. And still others might want to “dive in” and actively follow the clues and try to win the prize money, in which case they would be able to make full use of the other platforms that supported Push, Nevada. Ideally, as Tanz suggested, transmedia narratives should accommodate the full spectrum of audience members, from those who are primarily interested in passive entertainment to those who relish an extremely active experience.

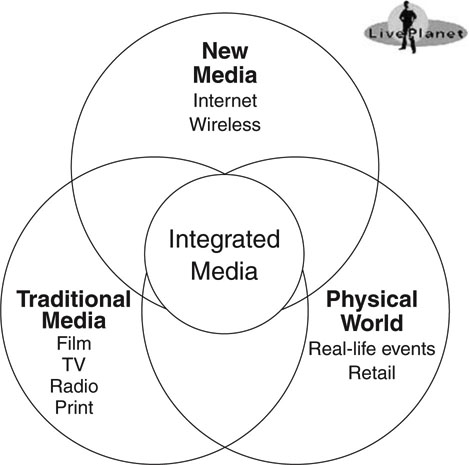

The concept behind Push, Nevada was exactly in keeping with the thrust of LivePlanet’s strategy at the time, and which they continue to use now with projects that lend themselves to it. The company terms this strategy as an “integrated media” approach. As Larry Tanz described it to me, it means developing a property and having it operate over three platforms: traditional media (TV, film, and radio), which is the “driver” of each project; interactive media (the Internet, wireless devices, and so on), which allows the audience to participate; and the physical world, which brings the story into people’s lives. The goal is to have these three platforms overlap in such a way that they are integrated at the core. (See Figure 9.2.)

Figure 9.2 With LivePlanet’s integrated media approach, properties are developed across multiple platforms and are integrated at the core.

Image adaptation courtesy of LivePlanet.

Despite the high hopes for the project, and despite the fact that the interactive components proved to be extremely popular, the TV component of Push, Nevada failed to catch on, and after only seven episodes, ABC discontinued the show.

By many other measurements, though, it was clear that many people were closely following the Push, Nevada story/game. About 200,000 people visited the Push, Nevada websites, making it one of the largest online games in history, according to ABC’s calculations. Over 100,000 viewers followed the clues closely enough to figure out the phone numbers of fictitious people on the show, call the numbers, and hear the characters give them recorded messages. In addition, about 60,000 people downloaded the “Deep Throat” conspiracy book written for the project. All told, ABC estimates that 600,000 people actively participated in the game.

TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING AND FEATURE FILMS

Less than a year after Push, Nevada debuted, another high-profile transmedia narrative was released, and like Push, Nevada, it, too, had roots in glamorous Hollywood media. This venture was the sequel to the enormously popular feature film, The Matrix. Unlike a regular movie sequel, however, it was not just another feature film. Instead, the producers, the visionary Wachowski brothers, created a transmedia sequel of breathtaking scope. It was composed of two feature films, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, and it also included a video game, Enter the Matrix; a DVD, The Animatrix; and a website, ThisistheMatrix.com.

This high-tech, new media crossover was particularly apt, given that the Matrix story depicts a society in which the digital and physical worlds collide and in which virtual reality runs amok.

As with all true transmedia narratives, each component of the Matrix collection of properties tells a different piece of the Matrix story. The two movie sequels and the video game were actually developed as one single project. The brothers Wachowski, Andy and Larry, who are reputed to be avid gamers, were at the helm of all three projects. All were shot at the same time. Not only did the Wachowskis write and direct the two movies, but they also wrote a 244- page dialogue script for the game and shot a full hour of extra footage for it—the equivalent of half a movie. In terms of the filming, the movies and game shared the same 25 characters, the same sets, the same crews, the same costume designers, and the same choreographers.

Although it is not necessary to see the movies in order to play the game, or vice versa, the games and movies, when experienced as a totality, are designed to deepen The Matrix experience and give the viewer–player a more complete understanding of the story. As one small example, in The Matrix Reloaded, the audience sees a character exit from a scene and return sometime later carrying a package. But only by playing Enter the Matrix will people understand how the character obtained that package.

The game contains all the dazzling special effects that are hallmarks of the movies, such as walking on walls and the slow motion bullets, known as “bullet time.” It was one of the most expensive video games in history to make, costing $30 million, and took two and a half years to complete. Nevertheless, despite the cost and a certain amount of criticism of the game and films, the game and the movies were a great success and benefited from the transmedia storytelling approach. Both the game and the first of the sequels, The Matrix Reloaded, debuted on the same day in May 2003 (a first in media history). By the end of the first week, the game had already sold one million units, selling a total of five million copies in all. As for The Matrix Reloaded, it earned a record-breaking $42.5 million on its opening day and a stunning $738,599,701 worldwide. (Though the second sequel, The Matrix Revolutions, fared somewhat less well, it earned a respectable $425,000,000 worldwide.)

HOLLYWOOD’S KEEN INTEREST IN TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING

Both the Push, Nevada story/game and The Matrix transmedia sequels were pioneering projects and were ahead of their time, but more recently, as noted in Chapter 2, mainstream Hollywood studios and producers have woken up to the fact that a transmedia approach to content can be an effective antidote to shrinking audiences, and it can also give them new revenue streams to tap.

As an excellent example of this new attitude, we can look at the pronouncement made by Jeff Zucker when he was CEO of the NBC Universal television group (he is now president and CEO of the entire NBC Universal empire). Mr. Zucker told Television Week (March 13, 2006) that he expected all producers of television shows to deliver packages that included not just television series but also content for the Internet, VOD, and mobile phones. “What it really means is producers can no longer just come in with a TV show,” he told the publication. “It has to have an online component, a sell-through component, and a wireless component. It’s the way we’re trying to do business on the content side, giving the consumer ways to watch their show however they want to watch it.” As Mr. Zucker clearly realizes, the use of multiple platforms is one way to reach audiences who have slipped away from TV, many of whom can now be found enjoying entertainment on their laptops and cell phones.

USING MULTIPLE PLATFORMS JUDICIOUSLY

Stephen McPherson, the president of ABC prime-time development, is the among the TV executives who are extremely enthusiastic about the use of multiple media. However, in an interview with the Los Angeles Times (January 3, 2006), he cautions that digital media should be used judiciously and not be allowed to dominate the content. “There are so many different aspects that go into all these multiple platforms that you just can’t say it’s a successful show, so let’s put it on 20 platforms,” he said. “But the idea that great content can be used in a multitude of different ways is a wonderful challenge and a wonderful opportunity.” In other words, careful thought and planning needs to be given to how to best use digital media to enhance a television series. Merely slapping it onto additional platforms for the sake of appearing trendy is a poor use of what they have to offer.

Producers themselves are beginning to take a more proactive stance when it comes to using multiple media for their productions. For example, Jesse Alexander, executive producer of such popular shows as Alias and Heroes, is a firm believer in such an approach. He told the Los Angeles Times (June 27, 2007): “We call it transmedia storytelling. When we create a new franchise, we talk about how we can extend the narrative as a game, as a book, how it would look on the Internet, and so forth.”

Thus far, however, the majority of producers and TV networks have not taken full advantage of the potential of transmedia storytelling. The majority of these new ventures use only two media (usually TV and the Internet, or TV and mobile devices), and very few offer interactivity.

For the most part, the transmedia material created for TV series has been in the form of webisodes and mobisodes—serialized stories told in extremely short episodes, one to six minutes in length, either for the Web or for mobile devices. These minidramas have spun out the TV series in a number of different ways. For example, a 10-part webisode was produced for the hit comedy, The Office. Called The Office: The Accountants, it was a story about a large sum of missing money and involved some of the background characters in the series, rather than the stars, giving the audience a chance to know them better. Sometimes a webisode will fill in pieces of the backstory of a TV series, as was done with the teen drama, Wildfire, with a webisode focusing on the life of the main character’s troubled life before the series begins. And in still other cases, a webisode fills in story gaps between TV seasons, as with the 10-part webisode of the sci-fi show Battlestar Galactica.

Sometimes, instead of creating a webisode, the TV series will create fictional blogs for their main characters and fictional bios for MySpace and Facebook.

Various techniques are being used for mobile devices, too, with spinoffs in the form of mobisodes being the most common approach. For example, the six-part mobisode made for Smallville, a TV series about Superman’s boyhood, told the backstory of an important character featured in the TV show, the Green Arrow. In a somewhat different approach, the mobisode 24: The Conspiracy, which was a spinoff of the TV suspense drama, 24, used the same type of storyline and same setting as the TV show, but a completely different cast of characters.

Several innovative projects have been undertaken by TV series that go beyond the typical webisode and mobisode approach. One interesting example is 24: Countdown, an online game built for 24, the same suspense drama mentioned above. Unlike the mobisode, however, this was a highly interactive venture, and it also tied together three types of media: network television, the Internet, and mobile phones. Players could actually take part in the same type of heart- pumping drama typically portrayed on the TV series and play a heroic role much like the star of the show, who works for a counterterrorist government agency. In the game, they work for the same counterterrorist agency and are tasked with the job of averting a nuclear catastrophe in a major American city, much like the scenarios in the TV series. In order to foil the terrorists, players must be able to receive urgent directives from counterterrorist headquarters. These messages are delivered to their cell phones, thus bringing the third media element into the narrative.

Nigelblog.com is another extremely clever transmedia venture tied to a TV series. Nigel is a character on Crossing Jordan, a crime drama set in a city coroner’s office in Boston. Nigel, one of the fictional characters in the show, shares his observations with viewers on a blog written in his character’s voice.

Occasionally, he even posts videos he makes with a webcam, sometimes secretly taping interchanges with other fictional characters. Though this example of transmedia storytelling only uses two media (TV and the Internet), it is highly interactive and also completely immerses viewers in the fictional world of the television drama.

For example, during the first season of the blog, Nigel solicited viewers’ help in solving several “cold case” murders, posting a number of clues on his blog. The blog created for the second season had a more personal twist to it, with Nigel asking viewers to help him handle a messy office love triangle. Throughout the season, Nigel encourages viewers to offer their advice on how to handle this complicated romance and frequently quotes their comments on his blog. In one of his blog entries, he decides that one of the characters embroiled in this romantic triangle needs to meet more women, and he asks viewers to write an online dating profile for the poor guy (with the winning profile posted for all to read). He also asks viewers to weigh in on the wedding dress choice of the prospective bride. And thus, real living people—the viewers—get to enter this fictional story and feel as if they are playing a meaningful part in it.

The Lost Experience, however, is possibly the most ambitious of transmedia storytelling applied to a TV series. The Lost Experience is an Alternate Reality Game (ARG) created around the TV drama, Lost, about a group of survivors of an airline crash marooned on a mysterious tropical island. The game was created by three TV companies, ABC in the United States, Channel 7 in Australia, and Channel 4 in the United Kingdom. The clues and narrative content were embedded in faux TV commercials and websites, in phone messages, in emails from characters, and in roadside billboards. In one eerie beat of this unfolding ARG, a “spokesperson” (actually an actor) from the Hanso Foundation even appeared on an actual late night TV show to defend his organization, which has played an ongoing and possibly nefarious role in the mystery.

Though the Lost ARG gave viewers the chance to actively participate in solving a mystery relating to the show and shed light on some of the secrets that had tantalized its viewers, it is worth noting that it did not reveal any essential parts of the narrative. Thus TV viewers who didn’t participate in the ARG would not miss any essential parts of the story, while viewers who played the ARG would enjoy a fuller experience of the Lost drama.

As ambitious as The Lost Experience was, it was by no means the series’ sole venture in transmedia storytelling. Lost has always been a leading innovator in the use of multiple platforms. For example, it created a mobisode called the Lost Video Diaries that featured the stories of other characters who were in the fictional airline crash but were not part of the TV drama. And in another bit of transmedia storytelling, viewers of the TV show would see a character find a suitcase from the wrecked plane that has washed up on the beach. Upon opening the suitcase, he discovers it contains a manuscript for a novel. Careful viewers who go to the trouble of looking up the title and author on Amazon.com will actually find the book listed, along with some information about the author being one of the passengers of an airline lost in midflight. Viewers could actually order the full-length book and read it, should they wish, or buy the audio version, and possibly pick up more clues about the Lost saga.

Carlton Cruse, the executive producer of Lost, told the Los Angles Times (January 3, 2006) how he regards the use of digital platforms to help tell the Lost story. “The show is the mother ship,” he stated, “but I think with all the new emerging technology, what we’ve discovered is that the world of Lost is not basically circumscribed by the actual show itself. … We have ways of expressing ideas we have for the show that wouldn’t fit into the television series.”

The Lost Experience and other transmedia narratives based on TV series have been extremely popular with viewers, giving them new ways to enjoy their favorite TV shows. From the networks’ point of view, they have been successful in achieving their twin goals of keeping audiences involved between episodes and seasons and in providing new revenue streams. And, for TV writers and producers, these new ventures have offered fresh ways to expand the fictional worlds they have created.

USING THE TRANSMEDIA APPROACH FOR NONFICTION PROJECTS

Although in most cases, the transmedia approach to storytelling has been used for works of fiction, this technique can also be successfully employed in nonfiction projects. For example, public television station KCET in Los Angeles used multiple media to tell the story of Woodrow Wilson, the president of the United States from 1913–1921, a project we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 13. The fulcrum here was a television biography, and two interactive components were developed in conjunction with it, a website and a DVD. By spreading the story of Wilson’s life over three different media, it was possible to portray him in far more depth than if this had solely been a TV documentary. Much thought was given about how to divide up the material about Wilson among the three different media to take advantage of what each had to offer.

On the other side of the globe, the South African company Underdog specializes in developing transmedia projects for nonfiction material, as we have noted. They’ve applied multiplatforming to a diverse array of works, including Big Brother Africa series; Mambaonline, a gay lifestyle property; All You Need Is Love, a teenage dating show; Below the Belt, a variety show; and loveLife, an HIV awareness project.

Underdog’s involvement in interactive media dates back to about 1994. They were the first production house in South Africa to have an online presence, and they began offering multiplatform production services to other companies, utilizing the new technologies as a way to facilitate interaction and communication. Luiz DeBarros, who cofounded the company with Marc Schwinges, described to me why they believe the transmedia approach is so important. DeBarros explains: “There is a passion to connect with audiences in new ways and to find content and strategies that best do this,” he said.

In developing a property across multiple media, DeBarros explained their goal is to do so using “a cohesive and synergistic strategy.” The technologies and media they utilize include cinema, television, DVD/CD-ROM, telephony, the Internet, games, wireless, and print, selecting whichever platforms are the most appropriate for the property.

For example, Big Brother Africa utilizes the following: websites and webcams; interactive television; telephony via IVR (Interactive Voice Response); and wireless, with SMS (Short Message Service). The concept of the TV series is much like others in the Big Brother franchise. A group of strangers is isolated in a house for a long period of time. Video cameras are planted around the house and run 24 hours a day, and viewers get to observe what happens. At various intervals, viewers vote on which housemate they want to have ejected until only one remains. To keep things lively, the housemates are given various challenges to perform. In the case of Big Brother Africa, the show starts with 12 housemates, one each from 12 different African countries. The technology utilized in producing the show allows viewers to watch the housemates online via streaming video as well as on TV. They can also communicate with other viewers in various ways, as well as read online features and news about the various contestants. While the program is being broadcast on TV, viewers can send in SMS messages, which are then scrolled across the bottom of the TV screen. Often these messages are written in response to something that is going on in the house, and they frequently trigger messages from other viewers, creating a kind of onscreen SMS dialogue on live television.

Endemol, the company that produces Big Brother Africa, stays on top of what the audience is saying by reviewing the content of online forums, chats, and email that has been collated by Underdog on a weekly basis. They often use this input to give a new twist or direction to the show, DeBarros said. As for the importance of the interactive components, he stressed that the show simply would not work without them. “There is a strategy that aims to create an audience loop that pushes people from TV to telephony, to iTV to the Internet, and back to TV,” he said.

When Underdog undertakes a new project, it prefers whenever possible to build in the transmedia components right from the beginning, while the project is still in the conceptual stage. And what does the company believe is the key to a successful production? Flexibility, DeBarros asserted; it’s of the utmost importance in situations where the audience is interacting with a property. A process needs to be established that can “assess audience impact and what is working and what isn’t, and adapt accordingly,” he said.

GUIDELINES FOR CREATING TRANSMEDIA NARRATIVES

In this chapter, we have described a number of transmedia narratives, and these projects used a great diversity of techniques and media to tell a story across multiple platforms. As different as they are from each other, however, we can learn some important general lessons from them that can be applied to other transmedia projects:

• As always, you need to understand your audience and provide it with an experience they will perceive as enjoyable, not as too difficult or too simple, or too confusing or overwhelming.

• Give members of the audience some way to participate in the narrative in a meaningful way. They want to have some impact on the story.

• When at all possible, develop all components of a project simultaneously, from the ground up, and work out how they will be integrated from the beginning, too.

• Each platform should contribute something to the overall story. Don’t just paste new components onto an already existing property without considering how they will enhance the narrative.

CONCLUSION

As we have seen from the projects discussed in this chapter, the transmedia approach can offer the user a new and extremely involving way to enjoy narratives and to interact with content. Forward-thinking broadcasters are looking at this approach as a way to potentially strengthen the connection between their viewers and their programming, an especially important goal as television audiences steadily decline.

Unfortunately, however, not all projects utilizing the transmedia approach have been successful, not even when supported by high budgets and produced by highly talented individuals. Yet it should always be kept in mind that creative ventures inevitably carry the possibility of failure, even in well-established areas like motion pictures and television. The risk is even greater when undertaken in a relatively uncharted area such as transmedia storytelling.

Clearly, the transmedia approach is an area that invites further exploration. Almost certainly, more experience with this approach will help content creators to find successful new ways of combining media platforms. We can also expect to see combinations of media not tried before. More work in this area should result in the creation of exciting new storytelling experiences.

IDEA-GENERATING EXERCISES

1. What kinds of projects do you believe are best suited to a transmedia approach, and why? What kinds of projects would you say do not lend themselves to this, and why? If you are doing this exercise as part of a group, see if someone else in your group can take the unpromising types of projects and come up with a transmedia approach for them that might work.

2. A variety of different media and communications tools have been employed in transmedia productions. Can you think of any media or tools that, to your knowledge, have not yet been employed? If so, can you suggest how such media or tools could be employed in an entertainment experience?

3. Discuss some possible transmedia approaches that could make a documentary or reality-based project extremely involving for the audience.

4. Try sketching out a story that would lend itself to a transmedia approach. What media would you use, and what would be the function of each in telling this story?