CHAPTER 13

Using Digital Storytelling to Inform

How and why are traditional media outlets like newspapers, news magazines, and television networks turning to interactive media as an adjunct to their news services?

How are digital storytelling techniques being applied to informational content?

In what ways are such disparate forms of digital media like interactive television, virtual reality, electronic kiosks, and interactive cinema being used to disseminate informational content?

What are some of the criticisms that have been leveled at the way digital media has been used to disseminate information?

THE IMPACT OF DIGITAL MEDIA ON NEWS AND INFORMATION

The proliferation of digital media is rapidly transforming the way we receive news and information. Until recently, most people obtained their news and information from print publications or from radio and television broadcasts. Now, however, digital technology is giving us new options. We can stay informed via websites, blogs, podcasts, and news bulletins delivered by email and in text messages on our mobile devices. We can receive the latest news almost as soon as it happens—and sometimes as it is actually taking place. With digital media, we also have the ability to customize the information we receive. We can choose the categories of content that interest us; we can specify whether we want to receive news bulletins or full stories; and we can determine when and how often we want to receive this content.

In addition to the Internet and mobile devices, we can receive information from iTV, DVDs, and electronic kiosks. These information-providing digital platforms can be found almost everywhere, from public spaces like cultural institutions and airports to private spaces like our homes, our schools, and our places of employment. In many cases, we carry them around with us in our pockets or handbags.

Not only is digital content highly portable and customizable, but it also gives us the opportunity to participate in the content. Newspapers allow for extremely limited forms of participation—readers can write letters to the editor and that’s about it. But interactive media allows us to contribute by sharing our stories and videos, voicing our opinions in forums and polls, and joining in live chats and other types of community experiences.

The radical shift in the way information is sent and received, as we noted in Chapter 2, is having a profound impact on traditional media and on how journalism is practiced. And, of particular interest to those of us involved in digital storytelling, these developments in the sphere of news and information are giving us the opportunity to use powerful new techniques of interactive narrative for informational purposes.

The Digital Revolution and Traditional News Media

The popularity of digital media is putting intense pressure on traditional news outlets. In Chapter 2, we described how competition from the Internet and other forms of digital media has caused newspaper circulation to plummet and audiences for televised news broadcasts to shrink. An article in the Santa Fe New Mexican (April 3, 2007) vividly described what traditional news sources are undergoing as being “under an unprecedented state of siege from the Internet.” As audiences shrink, so do ad revenues, which puts traditional news outlets in an ever-tighter bind.

In business, the customary response to competition is to engage in an all-out battle with the rival, seeking to beat down and eliminate the usurper. But in the case of the competition between traditional and digital news sources, many forwarding thinking newspapers and broadcasters are using a more adventurous strategy. They are embracing their rival, digital media, and integrating new types of interactive content into their operations.

For example, the Newspaper Association of America (NAA) has organized a special group, the Digital Media Federation, specifically to explore ways of harnessing digital media. The group has its own extremely vibrant website, The Digital Edge. For many newspapers, the embracing of digital media involves a shift of self-perception. As another article in the Santa Fe New Mexican put it (April 10, 2007), many papers no longer think of themselves as being in the “newspaper business” but simply as being in the “news business.” In other words, their primary mission is to deliver the news. The medium of delivery is irrelevant.

Most traditional news organizations that commit to digital media focus on developing a robust website and employ a large website staff. The website of The Washington Post, for example, has a staff of 200—larger than some newspapers. A few news organizations are taking a more proactive stance, teaching their reporters to develop stories for multiple media, using video and audio as well as print. Others are making significant changes in how and where they offer the news. For example, The Wall Street Journal puts breaking news and financial data on its website, and it uses its print publication for in-depth articles.

The changes in the way news is being covered is even sifting down to journalism schools, and it is impacting on the way news writing is being taught. At my old graduate school, the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, they are now training all students to use digital media to cover stories. Students learn to create blogs and websites; develop content for mobile devices; do podcasts; and write interactive narratives. They also learn to use an array of digital equipment. The professors have had to go back to school themselves to learn how to teach these new courses.

A few news organizations are doing more than just beefing up their websites. They are breaking new ground with digital media. For example, the news service Reuters has dispatched a reporter to cover the fast growing virtual world, Second Life. However, the reporter, Adam Pasick, does not just observe the world as a spectator. He has created his own avatar (whom he calls Adam Reuters) and regularly travels around inside Second Life to gather information for his stories.

The New York Times, as might be expected, is also taking some innovative approaches with digital media. For instance, it is now publishing video games as part of its page. These are serious games and, like an op-ed piece, they take a position on an important issue. The first such game, Food Import Folly, centers around the problems of imported food and the shortcomings of government food inspectors.

SETTING INFORMATION TO MUSIC

Not only is The New York Times beginning to produce games for its editorial page, but it has also started to produce musical videos for its website. Staff writer David Pogue, who covers technology, created the first such project for the paper. Pogue normally writes text-based stories, but when Apple introduced the iPhone in the summer of 2007, he couldn’t resist doing something totally different. He went all out and created a humorous musical video about the new device, portraying how he was obsessed with the desire to possess one. Though the musical took a tongue-in-cheek, mock-serious tone, the production also contained a thoughtful rundown of the iPhone’s assets and shortcomings. Pogue composed his own lyrics (to the tune of I Did It My Way) and even sang most of the music himself, though a few people waiting in line to buy iPhones were corralled into singing a few lines.

Not to be left in the dust, TV networks are also venturing out beyond the standard website approach in utilizing new media. For example, ABC/Disney developed a two-screen interactive TV show (using a website synchronized with the TV broadcast) for the 2007 Oscar awards. The production also included mobile devices, giving people the opportunity to download a backstage blog and highlights from the show. The material on the Web featured background stories about all the nominees, allowing viewers to get detailed information about anyone they were interested in. An interactive wrap-up of the show was produced for the website after the broadcast.

Using quite a different approach to digital media, CNN and YouTube joined forces in 2007 to produce a highly unusual debate featuring eight candidates for the 2008 U.S. presidential elections. The candidates, all Democrats, answered questions submitted in the form of YouTube videos. YouTube fans submitted nearly 3000 videos for consideration; 39 were selected for the debate. Most of the questioners in the videos were people asking about issues that personally concerned them. One humorous video, however, featured a snowman worriedly asking about global warming. The questions posed on the videos were unusually blunt for a presidential debate and sparked some lively discussions. The format was highly successful with viewers and drew far better numbers than the standard presidential debate. In fact, among adults aged 18– 34, a prime demographic, it received the highest Nielsen ratings of any debate ever broadcasted on a cable news network.

In still another approach, the cable TV network MSNBC has created an extremely rich and deep community-based website revolving around the Hurricane Katrina disaster in 2005. Called Rising from Ruin, the site contains stories written by professional journalists as well as individuals from the affected region. It includes numerous heartbreaking and inspirational first person accounts of the aftermath of this monumentally destructive storm, told in text, still photos, audio, and video. New stories are added on a regular basis, keeping the site fresh and current.

APPLYING DIGITAL STORYTELLING TECHNIQUES TO NEWS AND INFORMATION

Digital storytelling techniques can make an otherwise dry or difficult subject come alive, and it can make the material extremely engaging to users. The combination of information and entertainment gives us another genre of “tainment” programming—infotainment—a blending of information and entertainment, much as edutainment is a blending of education and entertainment. However, the term “infotainment” has fallen into disfavor because to some people it connotes a trivialization of factual content. Thus, even though the infotainment approach is perfectly valid when handled responsibly, we will refrain from using the term in this book because it might be distracting.

OBJECTIVE VERSUS SUBJECTIVE

We have many techniques at our disposal for making information engaging. But first of all, a basic decision must be made. Will we be taking a subjective or objective approach to delivering the content? Traditional journalism is objective. It is told in the third person and the writer avoids voicing his or her personal opinion. The facts in the story are checked out and validated; usually the sources of the facts are cited. A subjective approach, on the other hand, is a more personal one, and the material is often written in the first person. The writer’s opinion is clearly expressed, and facts may not be as carefully vetted or noted as with an objective approach. The subjective point of view is often used in blogs and personal websites. It is also fairly common in interactive documentaries and in audio and video podcasts and is even used in some informational games.

A fundamental goal in combining information, entertainment, and interactivity is to offer users an opportunity to relate to the material in an experiential manner, as opposed to one in which they are merely passive recipients of the information. The experiential approach to the presentation of information allows users to interact with it, participate with it, and manipulate it. As we will see, a variety of digital storytelling techniques can be used to create experiential forms of informational content.

Devising Interactive Narratives

One way to involve users is by creating highly involving and interactive personal narratives. This is the approach used in Rising from Ruin about Hurricane Katrina victims, described above. The same approach is being used in a website called the Hawai’i Nisei Story, an emotionally rich website featuring the stories of Hawaiians of Japanese descent and their often harrowing experiences during World War II. (Nisei is a Japanese term for second generation Japanese Americans.) The stories on this website are told in a mixture of video, audio, still photos, archival material, and text. Each person’s story is quite detailed, but users have the ability to choose their own path through the narratives and go as deeply as they wish.

Sometimes a story contains a natural narrative thread that can be exploited through good design and interactivity. This is the case with El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, a journey story about the old Spanish Colonial route from Mexico City to Santa Fe. The route is an historic landmark, and the 1500 mile-long road itself serves as the narrative thread here. El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro uses photographs, drawings, and audio to make the story of this road come to life. The project was produced by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

To create an effective narrative, the story or stories should be involving; multiple modes of communication should be employed; and users should have the ability to pick their own path through the material, as these works illustrate.

Community Building Elements

Users want to be able to personally participate in the story in some way. As we saw earlier in the description of Rising from Ruin, one method is to invite users to share their own personal stories. The website Participate uses a similar approach, inviting users to become investigative reporters and report on issues that concern them in their own communities. Participate grew out of the movie Good Night, Good Luck, a biography of the courageous television journalist, Edward R. Murrow.

Other community building techniques including inviting users to participate in polls; share their thoughts on forums, message boards, and listservs; and join in live chat sessions. Some community building techniques encourage the use of mobile devices: People can use them to vote, send in text messages, or even create videos to share with others.

Games and Gamelike Activities

Games are a highly effective way and popular way to involve users in informational material and to absorb it in an experiential manner. This technique was used by the game developed for The New York Times on food inspection, Food Import Folly. It was also used in two serious games described in Chapter 11, Darfur is Dying and Food Force.

The Internet abounds in informational games for all age groups and on a vast assortment of topics. Just to pick one example, let’s focus for a moment on a website called The MesoAmerican BallGame. The site was produced in conjunction with a traveling museum show, and it does an excellent job of involving the user in games and gamelike activities. The focus of this website is the ancient basketball-like sport played in Mexico and Central America, a game that was also a serious religious ritual. As you may recall, this game was described in Chapter 1.

The MesoAmerican BallGame gives users a chance to “play” a version of the ballgame itself, though they score points by answering trivia questions about the game instead of tossing the ball through the hoop. In addition, the website contains a number of gamelike activities. For example, users can bounce some of the traditional balls, and with each bounce, they learn an interesting fact about them. Another gamelike activity lets users dress one of the players in his game uniform. In addition to games and gamelike activities, visitors can “tour” a virtual ball court and learn more about how the game was played and also view MesoAmerican artifacts relating to the ball court. The website makes excellent use of animation, sound effects, music, and interactive time charts to make its subject matter vivid and understandable.

Using Humor

Humor is a traditional and effective way to make content engaging. We have seen how The New York Times used humor in its iPhone musical, a work clearly geared for an adult audience. But, as we discussed in Chapter 8, humor is also an excellent way to involve young people.

For instance, Yucky.com, a children’s informational site about biology, is filled with outrageous humor. This site proudly bills itself as “the Yuckiest Site on the Internet” but, in reality, it offers legitimate scientific content. It is hosted by a slimy reporter named Wendell the Worm, who offers features on disgusting (but fascinating) subjects like poop, zits, sweat, and dandruff—all as enticements to learn more about how the human body works. The site offers audio to underscore various points. On the poop page, for example, visitors can click on a button and hear a toilet flush. The site also gives a great deal of information about cockroaches. One of Wendell’s fellow denizens on Yucky.com is a character named Ralph Roach, who keeps a diary reflecting the daily life of a cockroach. Visitors to the site can read Ralph’s diary and take a virtual tour of roach anatomy. They can also play a fast-paced game of Whack-a-roach.

Offering Multiple Points of View

Because works of digital storytelling are nonlinear and interactive, they can be designed to give users the ability to explore information from more than one point of view. As we will see a little later in this chapter, this technique is sometimes used in interactive documentaries. It can also be employed in works of virtual reality, as was done in a work called Conversations, described in Chapter 22. By allowing users to see a work from more than one point of view, you give them the opportunity to examine the factual evidence in a number of ways and then come to their own conclusions. This is quite different from linear information content, which only provides one predetermined way of viewing the material.

AN ARRAY OF PLATFORMS

Throughout this chapter we have mentioned many different platforms that are used to deliver informational content. Now let’s look at them one by one and examine how each serves as a vehicle for information.

The Internet

When it comes to informational platforms, the Internet is certainly the grande dame of them all, having been used for this purpose far longer than another other digital medium. It now rivals traditional media as a delivery platform for information and news, and it is excellent at delivering densely factual material in an easily accessible manner. And, much in the manner of a grande dame, Web content can be beautifully dressed up in a great many ways. It can be enhanced by media elements like animation, video, sound effects, music and other types of audio, as well as by interactive elements like multiple narrative paths, diagrams with “hot spots,” games, timelines, and activities of various kinds.

However, the Internet’s content can also be “dressed down,” harkening back to the Internet’s modest roots as a text-based medium. Many informational websites are still primarily text-based, lacking most or all of the “glittery” elements we have described. In such cases (and even when there is plenty of “glitter”), the content needs to be organized in a way that is logical, easy to find, and “chunked” into small pieces, so users are not forced to read long stretches of text. Also, whenever possible, a narrative thread should be teased out of the source material so the content on the website tells an involving story. As experienced journalists know, engaging stories can be pulled out of virtually any source material and assembled in a compelling way.

WHAT IS TAXONOMY AND HOW DOES IT RELATE TO THE INTERNET?

In scientific circles, taxonomy is the discipline of classifying and organizing plants and animals. The underlying concept of taxonomy is extremely useful for organizing informational content on the Internet as well as other digital media. The word “taxonomy” comes from Greek and is composed of two parts: taxis, meaning order or arrangement, and nomia, meaning method or law. Though the organization of organisms in biology and the organization of text and graphics for a website might seem to be worlds apart, the basic approach is quite similar. In biology, taxonomy is a hierarchical system, starting with the largest category at the top, and then dividing the organisms into smaller and smaller categories, organized logically by commonalities. The same system works well on a website, and the underlying logic makes it easy for users to find the information they are looking for.

Mobile Devices

Mobile devices are increasingly being used as a portable tool to stay informed about breaking news, sports, weather, stocks, and entertainment. It is particularly useful for delivering short pieces of information. Owners of mobile devices can subscribe to any number of news services that will send the kinds of information they are interested in directly to their cell phones. Some of these news sources, like CNN and Reuters, were originally established for traditional media. Others, like Google Mobile, have their roots in new media. Many mobile devices can play video and can connect directly to the Internet, thus widely expanding their utility. Also, it should be stressed that mobile devices are designed as two-way streets. Not only can owners of them receive information, but they can also capture and send out breaking news—in text, stills, and video.

Interactive TV (iTV)

By making television content interactive, viewers can be pulled into the presentation and become actively involved in the program. It offers viewers a much richer connection to the informational content than they would have with a linear TV show. We briefly examined one example of iTV programming, the 2007 Oscar award show. A number of techniques can be used to enhance linear TV programming. They include access to background information (in text, audio, or video); play-along trivia games; participating in polls; and being able to vote in a contest or issue presented on the show and witnessing the results of the vote.

Virtual Reality (VR)

Virtual reality installations are unique in the way they can give participants a chance to connect with information content in a deeply experiential manner. As we will see in Chapter 22, VR can be used to immerse people in a recreated news story and observe it from multiple points of view, as with Conversations, the true story of a prison breakout. VR has exciting potential as a platform for experiential treatments of information content, but thus far its potential has barely been explored.

Electronic Kiosks

Electronic kiosks are ideal for offering informational content in a public setting, since they are reasonably portable, sturdy, and easy to operate. However, content for kiosk delivery must necessarily be quite concise, since kiosks must serve large numbers of people. They are well suited as informational delivery systems in government buildings, trade shows, and as adjunctions to museum exhibitions. The housing for kiosks can be dressed up in imaginative ways, serving as an enticement for visitors to try them out. Nonfiction content for kiosks is more thoroughly explored in Chapter 24.

Large and Small Screen Works of Interactive Cinema (iCinema)

Large screen iCinema productions, works that are viewed by audiences in theatres, are primarily found in cultural institutions. They are particularly well suited to nonfiction content that is emotionally engaging and offers an interactive exploration of a particular theme, such as marine life, astronomy, or human biology.

The more intimate works of small screen iCinema, designed for individual use, are an ideal platform for interactive documentaries because they encourage in-depth examinations of a particular subject or event. Such interactive documentaries offer multiple points of view, allowing users to experience the story from various angles. Others, known as database narratives, give users the chance to select and assemble small pieces of factual material into a cohesive story.

Examples of nonfiction projects for both types of iCinema can be found in Chapter 21.

Museum Installations

With digital technology, museum installations have the power to make static displays of artifacts become highly involving and interactive. To do this, museums are making use of animatronic characters, holographic images, and powerful sound and motion effects, as well as immersive environment techniques used in high tech theme park rides. A number of examples of how museums are using digital technology can be found in Chapter 22, on immersive environments.

Transmedia Productions

The transmedia approach to content, explored in depth in Chapter 9, presents an integrated narrative over a number of different platforms, and it allows users to experience the content and interact with it in a number of ways. Transmedia productions are not constrained in terms of length or style by a singe medium, and they provide a deeper and more dimensional understanding of informational material than does content delivered over a single platform.

To get a better understanding of how a nonfiction transmedia project works, let’s take a closer look at the biography of American President Woodrow Wilson, briefly described in Chapter 9. The project integrated a linear three-hour TV documentary with two interactive productions, a website and a DVD. Jackie Kain, VP of New Media for public station KCET in Los Angeles, was in charge of developing both the website and DVD.

As an initial step, Kain closely studied the core material. She noted that the documentary was “a rich story that was narrative driven” and therefore decided to capitalize as much as possible on its narrative qualities through the interactivity that would be offered. In addition, while the TV biography focused primarily on the international aspects of Wilson’s career, she decided to use the website and DVD to portray other parts of his presidency—his domestic policies and personal life. Thus, the interactive elements of the transmedia production would serve to round out this portrait of a president.

The website would be more text based, while the DVD would contain more video, thus coming at the same subject matter in somewhat different but complementary ways. They would be tied by a similar graphic design as well.

The website included an interactive timeline; commentary by historians; and additional information about the people, issues, and events that were important in Wilson’s life. One of the site’s most engaging and imaginative features was an activity called “Win the Election of 1912.” It challenged users to run their own political campaign to see if they could do better than other contenders in that historic race. Players got to invent the name of their party and then decide their stance on certain critical issues of the time. Based on their selections, they either won or lost the election.

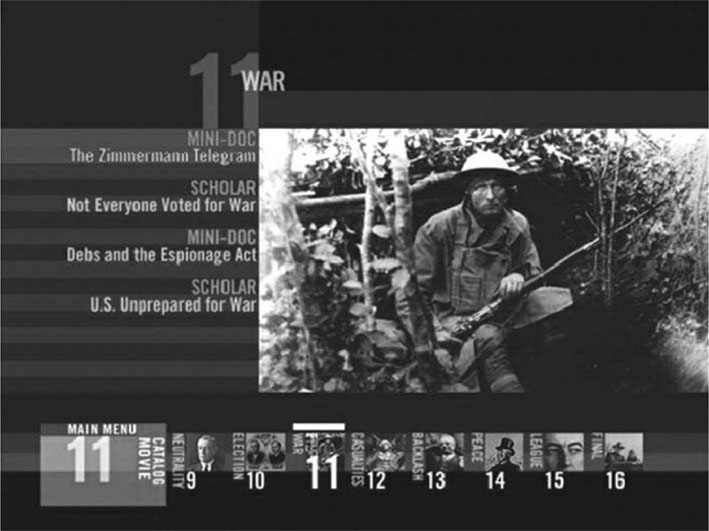

The DVD contained 80 minutes of video expressly produced for it, material not included in the TV show. This additional footage, broken into small “consumable” chunks, consisted of minidocumentaries and interviews with scholars. Kain described them as “short documentaries that tell you a story.” (See Figure 13.1.) Thus, the DVD and the website enhanced the TV documentary, and they did so in a highly engaging manner.

Figure 13.1 An image from the DVD that was part of the Woodrow Wilson transmedia production. The project tied together a TV biography, a website, and a DVD. This image shows the chapter menu for the DVD. The features on the left, the “mini docs” and the interviews with scholars, were made just for the DVD version of the biography.

Image courtesy of PBS, WGBH, and KCET.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR CREATING INFORMATIONAL PROJECTS

By their very nature, informational projects are based on facts, and factual material needs to be handled more carefully than material that is pure fiction, especially when incorporating the information into an interactive narrative. Care must be taken not to misconstrue or trivialize the facts or “dumb down” a complex issue. But on the other hand, you do want to create an engaging story that is not bogged down with an over-abundance of dry material. The answer to the following questions can help you shape a nonfiction project that marries factual material with digital storytelling and does justice to both:

• Will you be taking a subjective or objective approach to the factual material? If your point of view is a personal one, how will you make this clear to users?

• What narrative thread can you pull out of the source material that will be engaging to users and also give a fair representation of the various sides of the story? If your narrative thread is unbalanced in some way, how can you provide users with the opportunity to explore other sides of the story?

• In dramatizing the nonfiction material, are you providing ways for users to get all the important facts of the story? Will you build in ways for people to access supplementary material that is not part of the main narrative path?

• What kinds of interactive enhancements can you build in that will contribute to an understanding of the material?

• How will you give users an opportunity to participate in the story, so that it is not just a one-way street? Can they contribute stories of their own, or comments, or additional facts? Can they participate in polls relating to the story or vote on some aspect of it?

CONCLUSION

As we have seen, digital storytelling techniques, if handled carefully, can successfully be applied to virtually any type of informational project. In this chapter alone, we have discussed a diverse array of works, including biographies of unknown private citizens (Japanese-Americans in Hawaii) and of a powerful U.S. president (Woodrow Wilson); stories about a natural disaster (Hurricane Katrina) and a natural pest (the cockroach); interactive narratives about an historic landmark (El Camino Real) and a modern-day crime (Conversations); and others about a contemporary entertainment ritual (the Oscars) and an ancient cultural ritual (the MesoAmerican ballgame).

The “infotainment” approach to informational content has sometimes been criticized for trivializing serious content. Unfortunately, this allegation is quite valid in cases where the subject matter is oversimplified, or when entertainment elements overshadow the informational content, or when important facts are omitted.

However, the judicious use of digital storytelling techniques can actually be a tremendous asset to informational projects. By making the informational content engaging, they can entice people to learn about a subject they would ordinarily regard as too dull or difficult to be of interest to them. With interactivity, users can connect with the material in an experiential manner and come to a far deeper understanding of it.

Applying digital storytelling techniques to an information subject can work surprisingly well even for complex issues. Through interactivity and multiple story paths, these works can offer users more than one way to view the subject. A well-designed project can offer far more than a superficial presentation of a topic because users can view the material from different angles and dig deeply for additional information.

Some of the most multidimensional and multilayered works in the informational arena have been produced in the fields of VR and iCinema, and, unfortunately, they are largely unknown by the general public. Thus far, most members of the public have only had limited exposure to interactive informational narratives, and in the great majority of cases, they have encountered these works on the Internet. However, as other digital platforms like iTV and transmedia productions become more commonplace, we are likely to see exciting new developments in this area.

IDEA-GENERATING EXERCISES

1. Take a current news story that you have read about in a newspaper or magazine or seen on a TV news show. Imagine that you have been tasked with the job of turning this story into an interactive narrative for a news-oriented website. Sketch out how you would make it both informative and engaging. How could you involve users in the story?

2. Pick a subject from history and sketch out an idea on how you could develop it as an interactive narrative. What platform would you use? What digital storytelling techniques would you employ?

3. Select a current events topic that is the subject of public concern, such as global warming or terrorism. Sketch out an idea for an informational game on this topic.

4. Based on the discussion in this chapter of the website Yuky.com, “The Yuckiest Site on the Internet,” what other kinds of informational topics aimed at young audiences do you think might be made enticing by utilizing such an approach? Do you think such an approach could work for adults, too, and if so, on what types of subjects? If not, why not?