Live multi-camera production technique uses a number of cameras which are switched to in turn to show different viewpoints of an event. This production method allows the material to be transmitted as it occurs or to be recorded for future transmission. If it is recorded then the material can be edited before transmission. Single camera coverage is usually recorded and the material receives extensive editing before transmission. This is similar to the film technique where one shot is recorded and then the single camera moved to another position or location to record another shot. The shots can be recorded out of sequence from their subsequent edited order. This type of production method is very flexible but does require more time in acquiring the material and in editing. An additional advantage of the single video camera is that it can be linked into a programme by satellite, land line or terrestrial link and be used as a live outside visual source. Pictures are nearly always accompanied by audio, either actuality speech, music, or effects of the subject in shot, or sound is added in post-production. The old cliché that television is a visual medium is a half truth. In nearly every circumstance, the viewer wants to hear, as well as see, what is transmitted. Pictures may have a greater initial impact, but sound frequently adds atmosphere, emotion, and space to the image.

Two types of programming

Programmes can be roughly divided into those that have a content that has been conceived and devised for television and those programmes with a content that cannot be preplanned, or are events that take place independent of television coverage. Many programmes have a mixture of both types of content.

If it is scripted for television, then the production is under the direct control of the production team who can arrange the content as they wish. The time scale of what happens on the screen is under their supervision and can be started and stopped as required. If it is an event that would happen independent of TV such as a sports event, then the production team will have to make arrangements to cover the event as it unfolds in its own time scale.

The creation of ‘invisible’ technique

As we discussed in the section on basic camera technique (page 110), the ability to find ways of shooting subjects and then editing the shots together without distracting the audience was learnt by the commercial cinema over a number of years. Television production mostly follows this technique. A number of standard conventions are practised by all members of the production team with a common aim of disguising their specific craft methods in order to maximize the audience’s involvement with the programme content. If the audience becomes aware, for example, of audio transitions, change of shot or the colour cast on a presenter’s face, they are unlikely to be following developments in the programme.

Actuality event: Any event that is not specifically staged for television that exists in its own time scale.

Ad-lib shooting: Impromptu and unrehearsed camera coverage.

Camera left: Left of frame as opposed to the artiste’s left when facing camera.

Camera right: Right of frame as opposed to the artiste’s right when facing camera.

Canting the camera: Angling the camera so that the horizon is not parallel to the bottom of the frame.

Caption generator: Electronic equipment that allows text to be created and manipulated on screen via a keyboard.

Crossing the line: Moving the camera to the opposite side of an imaginary line drawn between two or more subjects after recording a shot of one of the subjects. This results in intercut faces looking out of the same side of frame and gives the impression that they are not in conversation with each other.

Cue: A signal for action to start, i.e. actor to start performing.

Cutaway: Cutting away from the main subject or master shot to a related shot.

Down stage: Moving towards the camera or audience.

Dry: Describes the inability of a performer either to remember or to continue with their presentation.

Establishing shot: The master shot which gives the maximum information about the subject.

Eyeline: The direction the subject is looking in the frame.

Grip: Supporting equipment for lighting or camera equipment. Also the name of the technicians responsible for handling grip equipment, e.g. camera trucks and dollies.

GV: General view; this is a long shot of the subject.

High angle: Any lens height above eye height.

High key: Picture with predominance of light tones and thin shadows.

Locked-off: Applying the locks on a pan and tilt head to ensure that the camera setting remains in a pre-selected position. Can also be applied to an unmanned camera.

Long lens: A lens with a large focal length or using a zoom at or near its narrowest angle of view.

Low angle: A lens height below eye height.

Low key: Picture with a predominance of dark tones and strong shadows.

Piece to camera: Presenter/reporter speaking straight to the camera lens.

Planning meetings: A meeting of some members of the production staff held for the exchange of information and planning decisions concerning a future programme.

Point-of-view shot: A shot from a lens position that seeks to duplicate the viewpoint of a subject depicted on screen.

Post-production: Editing and other work carried on pre-recorded material.

Prompters: A coated piece of glass positioned in front of the lens to reflect text displayed on a TV monitor below the lens.

Recces: The inspection of a location by production staff to assess the practicalities involved in its use as a setting for a programme or programme insert.

Reverse angle: When applied to a standard two-person interview, a camera repositioned 180° to the immediate shot being recorded to provide a complementary shot of the opposite subject.

Shooting off: Including in the shot more than the planned setting or scenery.

The narrow end of the lens: The longest focal length of the zoom that can be selected.

Tight lens: A long focal length primary lens or zoom lens setting.

Upstage: Moving further away from the camera or audience.

Virtual reality: System of chroma key where the background is computer generated.

Voice-over: A commentary mixed with effects or music as part of a sound track.

Vox pops (vox populi): The voice of the people, usually consist of a series of impromptu interviews recorded in the street with members of the public.

Wrap: Completion of a shoot.

See also other definitions in the Glossary, page 216.

Programme genres employ different production techniques. Sports coverage has shot patterns and camera coverage conventions, for example, different to the conventions used in the continuous coverage of music. Knowledge of these customary techniques is an essential part of the camerawork skills that need to be acquired. There is usually no time for directors to spell out their precise requirements and most assume that the production team is experienced and understands the conventions of the programme being made. The conventions can concern technique (e.g. news as factual, unstaged events, see page 130), or structure – how the programme is put together. A game show, for example, will introduce the contestants, show the prizes, play the game, find a winner and then award the prizes. The settings, style of camerawork, lighting and programme structure are almost predictable and completely different from a 30-minute natural history programme. It is almost impossible to carry over the same technique and style, for example, of a pop concert to a current affairs programme. Each production genre requires the customary technique of that type of format although crossover styles sometimes occur.

Attracting the audience’s attention

Whatever the nature of the programme, the programme makers want an audience to switch on, be hooked by the opening sequence and then stay with the programme until the closing credits. There are a number of standard techniques used to achieve these aims. The opening few minutes are crucial in persuading the audience to stay with the programme and not switch channels. It usually consists, in news and magazine style programmes, of a quick ‘taster’ of all the upcoming items with the hope that each viewer will be interested in at least one item on the menu. Either existing material will be cut to promote the later item or very often ‘teasers’ will be shot specifically for the opening montage. Whether in this fast opening sequence or in the main body of the programme, most productions rely on the well tried and trusted formula of pace, mystery and some form of storytelling.

Story

The strongest way of engaging the audience’s attention is to tell them a story. In fact, because film and television images are displayed in a linear way, shot follows shot, it is almost impossible for the audience not to construct connections between succeeding images whatever the real or perceived relationships between them. The task of the production team is to determine what the audience needs to know, and at what point in the ‘story’ they are told. This is the structure of the item or feature and usually takes the form of question and answer or cause and effect. Seeking answers to questions posed at the top of the programme, such as ‘what are the authorities going to do about traffic jams?’ or ‘how were the pyramids built?’, involves the viewer and draws them into the ‘story’ that is unfolding. Many items are built around the classical structure of exposition, tension, climax, and release.

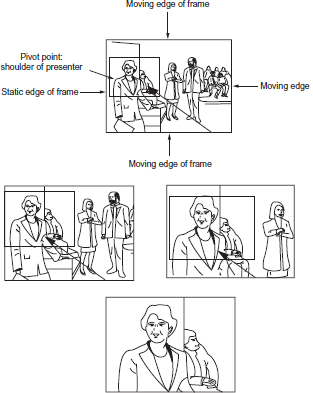

A common mistake with users of domestic camcorders is to centre the subject of interest in the frame and then to zoom towards them keeping the subject the same distance from all four sides of the frame. The visual effect is as if the frame implodes in on them from all sides. A more pleasing visual movement is to keep one or two sides of the frame at the same distance from the subject for the whole of the movement. Preselect one or two adjacent sides of the frame to the main subject of the zoom and whilst maintaining their position at a set distance from the main subject of the zoom allow the other three sides of the frame to change their relative position to the subject. Keep the same relationship of the two adjacent frame edges to the selected subject during the whole of the zoom movement. The point that is chosen to be held stationary in the frame is called the pivot point. Using a pivot point allows the subject image to grow progressively larger (or smaller) within the frame whilst avoiding the impression of the frame contracting in towards them.

Looking room

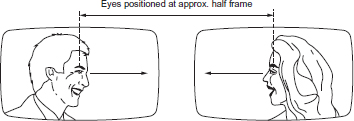

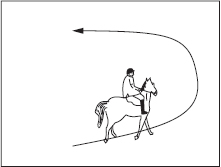

One of the compositional conventions of camerawork with profile shots, where people are looking out of frame, is to give additional space in the direction of their gaze for ‘looking room’. Similarly when someone is walking across frame, give more space in front of them than behind.

Headroom

Headroom is the space allowed above the head when framing a face. The amount of headroom will vary depending on the size of shot. In close-ups and big close-ups there will be no headroom. In long shots the amount of headroom will depend on location and composition. In general, the wider the shot the greater the headroom. It is only feasible to match headroom in medium close-ups and medium shots, other size shots will be framed on their individual merits.

Anyone new to camerawork will face the same learning curve as someone new to driving a car. They will be preoccupied with acquiring the basic skills of being fully conversant with the camera controls, focusing, framing and making certain they produce a technically competent image. Beyond the ‘L plate’ stage comes the recognition that there are many different ways of shooting a story.

Visual conventions

TV and film camerawork technique does not operate in a vacuum – there are past stylistic influences, contemporary variations and innovations caused by new production equipment. Most of these influences affect how productions are made but are rarely analysed by the practitioners. There have been changes in technique styles over the years so that it is not too difficult to identify when a TV production was shot. Retro fashion is always popular in commercials production and often prompts mainstream programme makers to rediscover discarded ‘old-fashioned’ techniques.

Equipment innovation

Equipment and technique interact and many programme formats have been developed because new hardware has become available. Kitchen drama in the 1960s was shot in a different way from previous styles of TV drama when ring-steer pedestals were developed and were able to move into the small box sets required by the subject matter and able to navigate the furniture. Steadicam and the Technocrane introduced a whole new look to camera movement and hand-held cameras reshaped breakfast shows and pop music videos. The new small DV format cameras are now opening up different stylistic methods of documentary production.

Two types of camerawork

An objective representation of ‘reality’ in a news, documentary or current affairs production uses the same perennial camerawork techniques as the subjective personal impression or the creation of atmosphere in fictional films. A football match appears to be a factual event whereas music coverage may appear more impressionistic. In both types of coverage there is selection and the use of visual conventions. Football uses a mixture of close-ups and wide shots, variation of lens height, camera position, cutaways to managers, fans, slow motion replays, etc., to inject pace, tension and drama to hold the attention of the audience. Music coverage will use similar techniques in interpreting the music, but with different rates of pans and zooms motivated by the mood and rhythm of the music. If it is a pop promo, there are no limits to the visual effects the director may feel is relevant. All TV camerawork is in one way or another an interpretation of an event. The degree of subjective personal impression fashioning the account will depend on which type of programme it is created for.

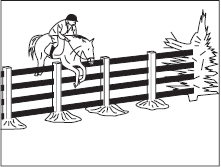

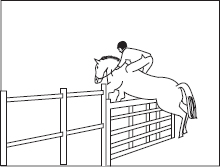

To cut from this shot…

to this shot…

you need this shot to show change of direction otherwise there would be a visual jump in the flow of shots

Keeping the audience informed of the geography of the event is the mainstay of standard camera technique. Shots are structured to allow the audience to understand the space, time and logic of the action and each shot follows the line of action to maintain consistent screen direction so that the action is completely intelligible.

There is an alternative camerawork style to the standard ‘invisible technique’ already discussed. Camera movement is often restlessly on the move, panning abruptly from subject to subject, making no effort to disguise the transitions and deliberately drawing attention to the means by which the images are brought to the viewer. This breaking down or subverting of the standard convention of an ‘invisible’ seamless flow of images was created from a number of different influences.

The camera surprised by events

When camcorders came into widespread use in broadcasting in the early 1980s, they were first used for news gathering before entering into general programme making. On-the-shoulder ‘wobblyscope’ became the standard trademark when covering impromptu action. War reporting or civil unrest was presented in news bulletins with the nervous ‘tic’ of a hand-held video camera. Realism appeared to be equated with an unsteady frame. Cinema verité in the early 1960s linked on-the-shoulder camerawork with a new flexibility of movement and subject but many film directors adopted the uncertainty of an unsteady picture to suggest realism and authenticity (e.g. Oliver Stone in JFK (1991)). Many productions mimic the camera movement of ENG news coverage which because the subject matter is unknown and unstaged is frequently ‘wrong footed’ when panning or zooming. Holding unpredictable action within the frame results in a different visual appearance to the calculated camera movement of a rehearsed shot. The uncertainty displayed in following impromptu and fast developing action has an energy which these productions attempt to replicate. Hand-held camerawork became the signature for realism.

Naïveté

Ignorance of technique may seem to be a curious influence on a style but the growth of the amateur use of the video camera has spawned a million holiday videos and the recording of family events which appear remarkably similar in appearance to some visual aspects of production shot in the ‘camera surprised by events’ style. The user of the holiday camcorder is often unaware of main-stream camera technique and usually pans and zooms the camera around to pick up anything and everything that catches their attention. The result is a stream of fast moving shots that never settle on a subject and are restlessly on the move (i.e. similar to the production style of NYPD Blue). Video diaries have exploited the appeal of the ‘innocent eye’. Many broadcast companies have loaned camcorders to the ‘man in the street’ for them to make video diaries of their own lives. The broadcasters claim that the appeal of this ‘camcorder style’ is its immediacy, its primitive but authentic image. It is always cut though by professional editors who use the same conventional entertainment values of maximizing audience interest and involvement as any other programme genre.

Video news journalism covers a wide spectrum of visual/sound reports which use a number of camerawork conventions. A loose classification separates hard news stories, which aim to transmit an objective, detached account of an event (e.g. a plane crash), from those soft news stories which incline more towards accounts of lifestyle, personality interviews and consumer reports. Acceptable camera technique and style of shooting will depend on content and the aim of the report. For example, a politician arriving to make a policy statement at a conference will be shot in a fairly straightforward camera style with the intention of simply ‘showing the facts’. An item about a fashion show could use any of the styles of feature film presentation (e.g. wide-angle distortion, subjective camerawork, canted camera, etc.). The political item has to be presented in an objective manner to avoid colouring the viewer’s response. The fashion item can be more interpretative in technique and presentation in an attempt to entertain, engage and visually tease the audience. A basic skill of news/magazine camerawork is matching the appropriate camerawork style to the story content. The main points to consider are:

■ the need to provide a technically acceptable picture;

■ an understanding of news values and matching camerawork style to the aims of objective news coverage;

■ structuring the story for news editing and the requirements of news bulletins/magazine programmes;

■ getting access to the story and getting the story back to base.

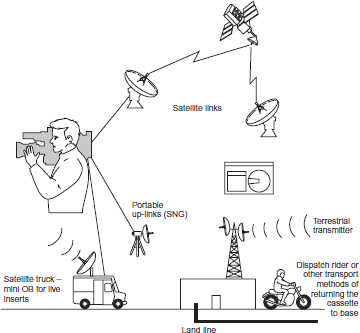

Returning the material

Getting the news material back to base can be by transport, land line, terrestrial or satellite link or foldaway SNG equipment. The important thing is to get the material to base fast with supporting information (if a reporter is not at the location) in a form (the cassette clearly marked) that can be rapidly edited. Use a separate tape for the reporter’s voice-over and a 5-minute tape for cutaways to speed up editing. Use a new tape for each story so that the stories can be cut independently if required.

There is no universally acceptable definition of news. A wide diversity of stories can be seen every day as the front page lead in newspapers. The only generalization that can be made in television is that news is usually considered to be those topical events that need to be transmitted in the next immediate news broadcast. Access, rapid working methods, a good appreciation of news values and the ability to get the material back, edited and on the air are the main ingredients of ‘hard news’ camerawork. There is no specific agreed technique in camera/recorder news coverage although there are a number of conventions that are widely accepted. People almost always take precedence over setting as the principal subject of news stories. Faces make good television if they are seen in context with the crisis. Where to position the camera to get the shot that will summarize the event is a product of experience and luck although good news technique will often provide its own opportunities.

Objectivity

A television news report has an obligation to separate fact from opinion, to be objective in its reporting, and by selection, to emphasize that which is significant to its potential audience. These considerations therefore needed to be borne in mind by a potential news cameraman as well as the standard camera technique associated with visual storytelling. Although news aims to be objective and free from the entertainment values of standard television story telling (e.g. suspense, excitement, etc.) it must also aim to engage the audience’s attention and keep them watching. The trade-off between the need to visually hold the attention of the audience and the need to be objective when covering news centres on structure and shot selection. As the popularity of cinema films has shown, an audience enjoys a strong story that involves them in suspense and moves them through the action by wanting to know ‘what happens next?’ This is often incompatible with the need for news to be objective and factual. The production techniques used for shooting and cutting fiction and factual material are almost the same. These visual story telling techniques have been learned by the audiences from a lifetime of watching fictional accounts of life. The twin aims of communication and engaging the attention of the audience apply to news as much as they do to entertainment programmes.

Access

One crucial requirement for news coverage is to get to where the story is. This relies on contacts and the determination to get where the action is. Civil emergencies and crisis are the mainstay of hard news. Floods, air/sea rescue, transport crashes, riots, fire and crime are news events that arise at any time and just as quickly die away. They require a rapid response by the cameraman who has to be at the scene and begin recording immediately before events move on. Equipment must be ready for instantaneous use and the cameraman must work swiftly to keep up with a developing story.

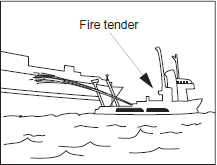

(a) Container ship on fire

(b) Container ship and fire tender, closer view

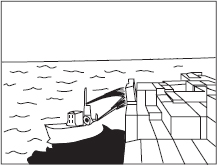

(c) Cruise ship in port, showing damage

(d) Disappointed holidaymakers

(e)

(f)

The above figures illustrate a news story reporting on a collision at sea between a container ship and a cruise ship. (a) shows the container ship on fire. Access is vital in news coverage and the cameraman must attempt to get to a position where the vital shot that summarizes the story can be recorded. (b) is shot on the container ship showing the ‘geography’ of the item of cargo and fire tender. (c) shows the damaged cruise ship in port and (d) is the disappointed holidaymakers leaving the ship while it is repaired. (e) is an interview with one of the passengers giving his experience of the collision and (f) is a piece-to-camera by the reporter (with an appropriate background) summarizing the story and posing questions of who/what was to blame.

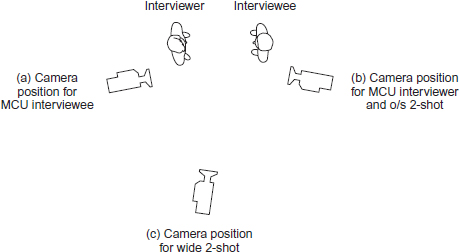

The interview is an essential element of news and magazine reporting. It provides for a factual testimony from a participant or witness to an event. Interviews can be shot in a location that reinforces the story and possibly gives more information to the viewer about the speaker (e.g. office, kitchen, garden, etc.). The staging of an interview usually involves placing the interviewee against a suitable background that may echo the content or reinforce the identity of the guest. Exterior interviews are easier to stage when there is a continuity of lighting conditions such as an overcast day or where there is consistent sunshine. The natural lighting will have to cater for three shots and possibly three camera positions – an MCU of the interviewee, a similar sized shot of the interviewer and some kind of 2-shot or ‘establishing’ shot of them both. If it is decided to shoot the interview in direct sunlight, then the interview needs to be positioned with the sun lighting both ‘upstage’ faces (i.e. the camera is looking at the shaded side of the face) using a reflector to bounce light into the unlit side of the face. The position of the participants can be ‘cheated’ for their individual close shots to allow a good position for modelling of the face by the sun. Because of the intensity of sunlight and sometimes because of its inconsistency, it is often preferable to shoot the interview in shade avoiding backgrounds which are in the full brightness of the sun.

Staging an interview

An interview is usually shot using a combination of basic shots which are:

■ an MS, MCU or CU of the interviewee;

■ a matched shot of the interviewer asking questions or reacting to the answers (usually shot after the interview has ended);

■ a 2-shot which establishes location and relationship between the participants or an over-the-shoulder 2-shot looking from interviewer to interviewee.

After the interview has been shot, there is often the need to pick up shots of points raised in the interview (e.g. references to objects, places or activity, etc.). In order for normal ‘invisible’ editing to be applied, the shots should match in size and lens angle between interviewee and interviewer.

Crossing the line

There may be a number of variations in shots available depending on the number of participants and the method of staging the discussion/interview. All of these shot variations need to be one side of an imaginary line drawn between the participants. To intercut between individual shots of two people to create the appearance of a normal conversation between them, three simple rules have to be observed. First, if a speaker in a single is looking from left to right in the frame then the single of the listener must look right to left. Second, the shot size and eyeline should match (i.e. they should individually be looking out of the frame at a point where the viewer anticipates the other speaker is standing). Finally, every shot of a sequence should stay the same side of an imaginary line drawn between the speakers.

■ Set interviewee’s position, first ensuring good background and lighting.

■ Then set interviewer beside camera lens (a) to achieve a good eyeline on the interviewee.

■ It is useful for editing purposes to precede the interview with details of name and title of the interviewee.

■ Remind the reporter and interviewee not to speak over the end of an answer.

■ Do not allow interviewee to speak over a question.

■ Agree with the journalist that he/she will start the interview when cued (or take a count of 5) when the camera is up to speed.

■ Record the interviewee’s shot first, changing size of shot on the out-of-frame questions.

■ Reposition for the interviewer’s questions and ‘noddies’ (b). An over-the-shoulder 2-shot from this position can be useful to the editor when shortening the answers.

■ Match the MCU shot size on both participants.

■ Do cutaways immediately after interview to avoid changes in light level.

■ Always provide cutaways to avoid jump cuts when shortening answers.

■ A wide 2-shot of the two participants talking to each other (without sound) can be recorded after the main interview if the shot is sufficiently wide to avoid detecting the lack of lip sync if the shot is used for editing purposes in mid-interview (c).

■ Watch that the background to an establishing 2-shot is from a different angle to any cutaway shot of the subject. For example, a wide shot of the ruins of a fire is not used later for the background to an interview about the fire. This causes a continuity ‘jump’ if they are cut together.

■ Think about sound as well as picture, e.g. avoid wind noise, ticking clocks or repetitive mechanical sound, etc., in background.

■ Depending on the custom and practice of the commissioning organization that cut the material, use track 1 for v/o and interview, and use track 2 for effects.

■ Indicate audio track arrangements on the cassette and put your name/story title on the tape.

The ability to broadcast live considerably increases the usefulness of the camera/recorder format. As well as providing recorded news coverage of an event, a single camera unit with portable links can provide live ‘updates’ from the location. As the camera will be non-synchronous with the studio production, its incoming signal will pass through a digital field and frame synchronizer and the reconstituted signal timed to the station’s sync pulse generator. One advantage of this digital conversion is that any loss of signal from the location produces a freeze frame from the frame store of the last usable picture rather than picture break-up.

Equipment

Cameras with a dockable VTR can attach a portable transmitter/receiver powered by the camera battery in place of the VTR. The camera output is transmitted ‘line of sight’ to a base antenna (up to 1000 m) which relays the signal on by land line, RF link or by a satellite up-link. Other portable ‘line of sight’ transmitters are designed to be carried by a second operator connected to the camera by cable.

When feeding into an OB scanner on site, the camera/recorder operator can receive a return feed of talkback and cue lights, whilst control of its picture can be remoted to the OB control truck to allow vision control matching to other cameras. It can therefore be used as an additional camera to an outside broadcast unit. In this mode of operation it can supply recorded inserts from remote parts of the location prior to transmission. During transmission the camera reverts to being part of a multi-camera shoot. Unless there is very rapid and/or continuous repositioning, mount the camera on a tripod.

Good communications are essential for a single camera operator feeding a live insert into a programme. Information prior to transmission is required of ‘in and out’ times, of duration of item and when to cue a ‘front of camera’ presenter if talkback on an ear piece is not available. A small battery-driven ‘off air’ portable receiver is usually a valuable addition to the standard camera/recorder unit plus a mobile phone.

A single camera insert can be a very useful programme item in a fast breaking news story, providing location atmosphere and immediacy, but because it is a single camera any change of view must be achieved ‘on shot’. This may involve an uncomfortable mixture of panning and zooming in order to change shot. If the story is strong enough, then absorbing content will mask awkward camera moves. Alternatively, a cut back to the studio can allow quick reframing at the location.

If two cameras are used, some method of switching between them is employed via a small field vision mixing panel operated by the director. Because this is a very simple set-up there will be no cue lights fed to the cameras and the operators will therefore need to be informed when they are ‘on’ and ‘off’ shot by radio talkback. Cameras need to be jointly white balanced and matched in exposure before the insert.

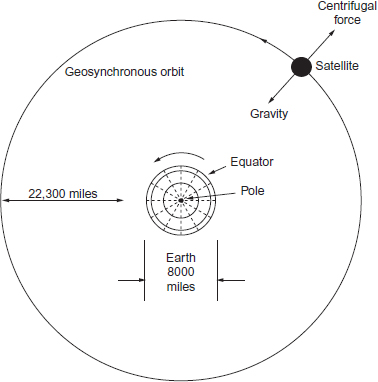

In order that an SNG unit can continuously transmit an unbroken signal without constantly realigning its dish aerial, the satellite must be placed in an orbit stationary above the earth. This is achieved by placing the satellite in an orbit 22,300 miles from the earth where it is held in place by the balance between the opposing force of the gravity pull of the earth against the centrifugal force pulling it out into space. Geosynchronous orbit (GEO) satellites revolve at the same rotational speed as the earth and appear stationary from the earth’s surface. Signals can be transmitted to and from them with highly directional antennas pointed in a fixed direction. It is the satellites’ fixed position in relation to earth that has allowed the growth of small, portable dish transmitters.

Orbital arcs

The number and position of the satellites located in this orbital arc 23,300 miles above the earth are regulated by a number of world-wide authorities. The satellites are positioned, after the initial launch, by a gas thruster which ensures they keep their position 2° from adjacent satellites. Frequencies used for communications transmission are grouped into Ku band (10.7–18 GHz) and C band (3.7–4.2 GHz). The Ku band is almost universally used for portable SNG service because the antennas are smaller for a given beam width due to the shorter wavelength, and the freedom from interference to and from microwave systems.

There are problems with transmission paths to satellites positioned close to the horizon and therefore some orbital slots are more favourable than others. A minimum elevation angle of 10° to 20° for Ku band is required to avoid difficulty in clearing buildings, trees, and other terrestrial objects, atmospheric attenuation, and electrical noise generated by heat near the earth’s surface.

Like news, magazine items often attempt to capture spontaneous action and present an event objectively. But whereas news is generally topical information of the day, shot on the day, magazine themes and issues are shot over a period of time. A news item may have a duration of less than 30 seconds while a ‘feature’ report can run for 3 to 5 minutes. All these factors have a bearing on the camera techniques that are used on the different genres.

News attempts to emphasize fact rather than opinion although journalistic values cannot escape subjective judgements. Feature items can use fact, feeling and atmosphere, argument, opinion, dramatic reconstruction and subjective impressions which can be very similar to standard feature film storytelling. Non-topical items can be filmed and edited, and often shelved as stand-by or they can be used to balance the programme when required. Without the immediate pressure to transmit, they can have more considered post-production (e.g. the addition of music and effects).

Diary events

Many topics that are featured in news and magazine programmes are known about a long time before the event occurs. These ‘diary’ events allow forward planning and efficient allocation of people and time. They also provide the opportunity for advanced research and a location shoot can be structured and more considered.

Even if a ‘diary’ item is considered to be predictable and straightforward, be flexible on the day and be prepared for the unexpected (e.g. an unexpected demonstration by protesters in the middle of a VIP tour).

Abstract items

Many issues dealt with by factual programmes are often of an abstract nature which at first thought have little or no obvious visual equivalent. Images to illustrate such topics as inflation can be difficult to find when searching for visual representations. Often the solution, with the above example, is to fall back on clichéd shots of shoppers and cash tills with a great deal of voice-over narration providing the explanations.

Whatever the nature of a news story there must be an on-screen image, and whatever is chosen, that picture will be invested by the viewer with significance. That significance may not match the main thrust of the item and may lead the viewer away from the topic. For example, a story about rising house prices may feature a couple looking at a house for sale. To the viewer, the couple can easily, inadvertently, become the subject of the story. Consider the relevance of all details in the shot, and have a clear idea of the shape of the item, its structure, and what it is communicating.

Music coverage with a single camera

Non-sync close-ups

Non-specific cutaways

Continuous sound track

A first priority of single camera coverage of a musical item is to make certain there is a well-balanced continuous sound track of the complete piece.

Master shot

Record a master shot with a continuous sound track of the whole musical item. This can take the form of a wide shot of the musicians (or a closer shot in the case of a solo musician), with a couple of camera repositions to give variety to the shot if you are certain the moves can be covered by cutaways or you provide a continuously usable shot.

Avoid using the camera-mounted microphone on music or you risk a selective musical balance, depending where the camera is centre framed.

Second performance

On a second performance of the music, provide the editor with a variety of close shots such as faces (non-singing) that can be cut into the master even if slightly out of sync, but avoid shots of fingering on instruments that may have to be precisely matched up to sync sound – especially keyboards and timpani. If there are vocals, record a third performance featuring complete choruses of singers. These may or may not be usable, depending on the type of music and the ability to cut between takes.

Cutaways

Non-performance shots of the artistes in any location can also help the editor, plus decorative shots of nature, light and location objects.

A documentary about two young men contained a sequence of them climbing a fence into a compound and apparently stealing wooden pallets and a wheelbarrow. The director admitted this was staged with the permission of the owner of the yard. He claimed this was done to avoid the unit being involved in an illegal act. He justifies the reconstruction because he claimed the theft would have taken place even if they were not being filmed. This is a common excuse for what is in effect a ‘reconstruction’. If the protagonists were likely to do some kind of action, they can be asked to perform it or act out a similar sequence because it is in character. If ‘reconstruction’ had been supered over the robbery it would have made the documentary less convincing to the viewer because there is no point in watching a poor piece of fiction as the impact and interest of the sequence was premised on the belief that it was ‘real’. Is the viewer watching a ‘real’ event if the director stages what the participants normally do?

The viewing public have only just woken up to the fact that most documentaries are staged in some way or other. ‘Reality’ programmes are very popular with viewers, but the question facing any would-be documentary cameraman or director is ‘how much manipulation does it take to put “reality” onto the TV screen?’

Objectivity

Like news, documentary often attempts to capture spontaneous action and present a slice of life avoiding influencing the subject material with the presence of the camera. But there is also the investigative form of documentary; an exposé of social ills.

Whereas news is generally topical information of the day, shot on the day, to be transmitted on that day, documentary themes and issues are shot over a period of time. The documentary format is often used to take a more considered look at social concerns than may have occurred in the form of a quick specific event in a news bulletin.

Conventional documentary style

A standard documentary structure, popular for many years, involves an unseen presenter (often the producer/director) interviewing the principal subject/s in the film. From the interview (the questions are edited out), appropriate visuals are recorded to match the interviewee comments which then becomes the voice-over. A professional actor is often used to deliver an impersonal narration on scientific or academic subjects. The choice of the quality of the voice is often based on the aim to avoid an overt personality or ‘identity’ in the voice-over whilst still keeping a lively delivery.

The camera can follow the documentary subject without production intervention, but often the individual is asked to follow some typical activity in order for the camera to catch the event, and to match up with comments made in previous interviews.

A documentary purporting to follow (without intervention) the criminal activity of two young men breaking into and stealing from a builder’s yard. The director of the documentary had got prior permission from the owner to allow this to happen. Was this sequence fact or fiction?

Stylized documentary

Television documentary attempts to deal with the truth of a particular situation but it also has to engage and hold the attention of a mass audience. John Grierson defined documentary as ‘the creative treatment of actuality’. How much ‘creativity’ is mixed in with the attempt at an objective account of the subject has been a subject of debate for many years.

‘Verité’ as a style

The mini DV camera format has allowed the ‘verité’ style to proliferate. This type of documentary attempts to be a fly-on-the-wall by simply observing events without influence. It over-relies on chance and the coincidence of being at the right place at the right time to capture an event which will reveal (subjectively judged by the film maker at the editing stage) the nature of the subject. With this style, the main objective of being in the right place at the right time becomes the major creative task. There is often an emphasis on a highly charged atmosphere to inject drama into the story. It may use minimum scripting and research other than to get ‘inside’ where the action is estimated to be. The style often incorporates more traditional techniques of commentary, interviews, graphics, and reconstruction, using hand-held camerawork and available light technique.

Wildlife

Documentaries featuring the habitat and lives of animals are a perennially popular form of documentary. They often involve long and painstaking observation and filming to get the required footage added to some very ingenious special effects set-ups. A programme about the Himalayan black bear also featured a sequence of the bear hunting for honey on a tree trunk that was filmed in Glasgow Zoo. The director said it would have been impossible to film it in the wild and it was needed because it made the sequence stronger. It is commonplace in wildlife programmes to mix and match wild and captured animals.

Docusoap

The spontaneous style of ordinary people observed strives for ‘realism’ and neutral reportage but gives no clues to what has been reconstructed. The viewer is sucked into a totally believable account. Many professional film makers protest that the viewer understands their subterfuge and fabrication and they are forgiven for the sake of entertainment, involvement and pace. But do viewers understand the subtleties of programme making? The viewer needs to question what they are shown, but as ‘invisible’ techniques are designed to hide the joins, how can the viewer remind themselves at each moment that they are watching a construct of reality? A documentary crew followed a woman who repeatedly failed her driving test. One sequence involved the woman waking her husband in the middle of the night with her worries. Did the viewer question if the crew had spent each night in the bedroom waiting on the off-chance that this was going to happen or did they immediately think ‘this is a fake – a reconstruction’?

Secret filming allows evidence to be collected that is obtainable by no other method – it is an unglamorous version of crime. Its raw appearance feels closer to reality but there is the danger of becoming obsessed with the form of surveillance/secret filming, and how something was shot becomes more important than the reason it was shot. The stylized conventions of secret filming and the imitation of raw footage such as ‘grained up’ images, converting colour images to black and white, shaky camerawork and the appearance of voyeurism is a developed programme ‘style’.

Video diary format takes the viewer back to themselves, back to the routine and the ordinary which becomes novel and new because it is unlike ‘reality’ portrayed in the fiction programmes. It allows people to put forward their own idiosyncrasies which differ from documentaries made by TV professionals. Are people spending too much time watching ‘reality’, leaving no time for their own reality?

Surveillance compilations

The other programme fashion is a proliferation of surveillance camera compilations. These use police car chases, city centre fixed cameras of street crime, etc. This ‘reality’ TV also includes secret filming and the self-documentation of video diaries. The very roughness of surveillance images guarantees total authenticity. The appeal of this video reality TV is that it is perceived as real – it is not recreation. New technology can go where TV cameras have never been before.

There is in fact a new lust for authenticity – no interpretation, just a flat statement of reality. Programme production has been able to achieve increasing standards of glossiness which can be contrasted with the charge of rawness – the jolt of raw footage which is unmediated – a direct access to the real without modification.

Video diaries

Video diary format takes the viewer back to themselves, back to the routine and the ordinary which becomes novel and new because it is unlike ‘reality’ portrayed in the fiction programmes. It allows people to put forward their own idiosyncrasies which differ from documentaries made by TV professionals.

Privacy and the mini DV camera

As mini DV cameras can be positioned anywhere and provide continuous coverage, the question raised is do our lives belong to ourselves or can they be just another product for public display and consumption?

If video cameras are used to record more and more of the ordinary and mundane parts of people’s lives, will their life only exist through their recordings? Will they only experience their life by watching a playback of it on a TV screen as holidaymakers experience their holidays through a viewfinder and then later through a snapshot album?