Communicating with Chinese by understanding them better

Abstract:

This chapter starts with basics in communication then moves on to the cross-cultural communication, in specific communication with China. It introduces the concept of high-low context culture and language and communication styles. With real case examples it demonstrates how relationships are built in doing business with Chinese.A main point of this chapter is on the Glass Wall Effect, explains what it is and why it is more dangerous than no knowledge at all. It goes on to explain the pros and cons of using an interpreter and how miscommunication may occur. Suggestions are given to Western companies to ensure that they have their own interpreters when negotiating with Chinese.

high and low context culture and language

relationship building with Chinese

miscommunication across cultures

explains the role of interpreters in cross-cultural communication

The increasing use of globalisation as a strategy for growth leaves organisations no choice but to ensure they have effective cross-cultural communication skills and processes in place. Communication is fundamental to all business activities, and cross-cultural communication is far more complex than mono-cultural communication. The problems of communicating with multiple stakeholders embedded in diverse cultures are complex. This is exacerbated by the linking of macro-cultural issues, such as globalisation, with micro-cultural and community identity issues.

Communication models

To help understand communication, let us look at some basic communication models. The model used by Shannon and Weaver (Dwyer 2002, p. 53) has been the most popular so far in improving communication in organisations (see Fig. 2.1).

Its main elements (sender, receiver, encoding, decoding, channel, message and context) explain factors behind ineffective communication. Factors such as culture, technology, environment, individual differences and others may affect these basic elements, which indicate the complexity of any effective communication process.

Within one culture, barriers to communication occur at any point. For instance, individuality determines how a sender may encode a message. Within one cultural community, Foster’s Group head office in Melbourne for example, certain protocols exist for how a message should be sent. When a sender behaves abnormally (as perceived by others and they are usually from the same cultural group), the receiver will have difficulty in decoding the message. This may cause suspicion or distrust, or possibly even a conspiracy theory, in processes of communication. Further misunderstanding may occur through the feedback loop, which in most cases is how a misunderstanding is discovered. When a misunderstanding is not recognised by either the sender or receiver, behaviour framed by the misunderstanding will influence the new pattern of communication. This will cause further misunderstandings and, in turn, damage relationships.

In communication with Chinese, this process is often the main cause of misunderstanding, because culturally Chinese are less likely to clarify issues for two reasons:

1. Their communication style – high context compared with low context.

2. The culture of being vague as well as polite, ‘hanxu (含蓄)’ is considered a good quality in a person.

Different behavioural patterns may cause inefficiency in a cross-cultural communication process. Misunderstanding across different cultures is harder to recognise than in mono-cultural communication and is more difficult to deal with. Cultural capability is caused by an inability, or varying degrees of ability, to interpret cross-cultural behaviour. Not understanding culturally related behaviour often results in a complete misunderstanding when encoding and decoding messages. Communication is, in effect, blocked not by one barrier but by too many barriers.

Increasing diversity worldwide has drawn much attention to cultural issues in communication. Previous literature suggests that in communication across cultures, context is the component that causes most difficulties. Cultural differences substantially affect the process of message transmission.

Context of culture and cross-cultural communication

Edward Hall’s theory of high context and low context culture is fundamental to the understanding of cross-cultural communication and styles. Hall (1976) suggested that on a continuum of a scale, people of different cultures can be divided into high and low context.

Context is the information that surrounds an event; it is inextricably bound up with the meaning of that event. The elements that combine to produce a given meaning – events and context – are in different proportions depending on the culture. The cultures of the world can be compared on a scale from high to low context (Hall and Hall 1990).

High and low context is a continuum scale that indicates the degree to which someone is aware of the selective screen that they place between themselves and the outside world. I find this concept is one of the most useful in explaining the differences between individuals, and at the same time, the concept is broad and covers such large groups and numbers of people.

On a macro level, the concept is brilliant and even on a micro level I have used it to explain many situations, and people are generally enlightened by it. However, for every example one can possibly find an exception.

People of high context culture communicate with high context messages in a high context manner, and vice versa in low context culture. In high context, the unspoken meaning is at least as important as what is actually said, while in low context culture most of the information is expressed explicitly. In high context culture, people express themselves with many and a large variety of words. They go around the issues and expect the listener to understand the hidden agenda. The speaker expects the listener to follow their train of thought and to pick up the meaning between the words. Surrounding context and background information are part of what is expected to be familiar to all. Among people of the same culture, this is achieved without the need for clarification.

For instance, in negotiations, Chinese often use the expression, ‘the price is too high’ as a smokescreen. This can have several meanings, such as: the price is genuinely too high and the other party needs to bring it down; or there is a hidden agenda because the real issue is not price, but they cannot express the real issue concisely.

It is expected that the other party, if also from a high context culture, will pick this up and quickly work out exactly what the real issue is. However, not understanding the cultural background makes it difficult, if not impossible, to decode the real meaning. The importance of this concept of high and low context is clearly seen in miscommunication between cultures or alternatively the ease with which people of the same cultural group communicate.

Communication in a high context culture takes much longer to reach the point of exchange (Korac-Kakabadse et al. 2001) and it contains attempts to smooth over any unpleasant information that has to be conveyed (Hall and Hall 1990). It has been said that the difference between Americans (low context) and Japanese (high context) is: ‘When we say one word, we understand 10, but here (in Japan) you say 10 to understand one’ (Kennedy and Everest 1996). People of low context culture are so economical in using words. They put meaning to each word and only express the exact meaning of the words they use. For people of high context culture, meanings cannot be expressed directly; to do so is simply rude.

This difference between the two cultures has a big effect on the effectiveness of their communication. Culture is the primary force of human behaviour and hence communication style. The differences, or the inability to interpret correct meanings from people of one culture to another, are the main barrier to effective cross-cultural communication. Using language as the only excuse is shallow. Language difficulties are merely symptoms rather than the cause.

Building relationships at all levels

Culture as a whole can be likened to an onion. There are many layers to the concept of culture, hence the cause of difficulty may appear at many different levels, which often causes confusion in a cross-cultural context.

Communication in a high context culture usually involves multiple levels of relationships in different situations. For instance, when Chinese receive Western visitors in China, the visitors will be looked after for the duration of their stay. From morning to night, programs and activities are organised from the minute they arrive to when they board the plane to depart. The hosts will extend hospitality to accompanying family and friends or at least say, ‘Next time, bring your family.’

Chinese ensure that all visitors are well looked after and entertained as a part of relationship building and it is considered good manners and appropriate hospitality. To keep visitors accompanied ‘peizhe (陪着)’ is basic manners for hosts and hostesses. Often when facilities permit, visitors’ accommodation costs are usually also covered. Difficulties occur when Chinese visit Australia. Unenlightened Westerners expect them to get from airport to hotel by themselves, and entertain themselves when there are no business-related activities.

Not only is the reciprocal level of hospitality poor in Chinese eyes, but they are often at a loss to understand why. Serious consequences have occurred from these types of inhospitable arrangements and sadly few lessons have been learned, as an example from a few years ago shows.

A Chinese mining company visited Melbourne to negotiate a contract with BHP Billiton. The meeting was held promptly on time at BHP’s office. At its 12.30 pm conclusion, the Chinese were politely shown the way out. Standing in the street with little idea where they were, they phoned a Chinese friend who one of the delegation members knew. The conversation ensued:

‘We just had our meeting with BHP.’

‘Well, and we just finished now.’

‘Good, are they taking you to lunch?’

‘Not really, as a matter of fact we are just standing here at (location), wondering where we should go for lunch.

At lunch, the Chinese delegation disclosed the purpose of their trip and when asked how the negotiations went, they said: ‘We need to buy this much of (product). Do you want the contract?’

BHP negotiators would not have found out about this mistake because they would simply have assumed the Chinese were insincere and did not get back to them.

On another occasion one of the many higher education institutions in Melbourne with a large number of Asian students told some visitors from a Chinese university to ‘grab a cab and come to (destination)’ when they phoned from the airport. They did and arrived for the scheduled meeting. Afterwards they were left to stop another cab themselves, on a freeway at 1 pm. The Chinese delegates waited 45 minutes before a cab would stop. Needless to say, they never returned to the Australian university.

The Australian university simply commented later: ‘Chinese universities often come and visit, but never come back.’ No one even asked the question, if a delegation (usually more than four people) bother to spend tens of thousands of dollars visiting Australia, why would they not wish to produce an outcome?

Questions and answers not always straightforward

Low context culture people discuss very specific topics. They ask specific questions, straight to the point, and expect direct answers. They are seldom able to read behind the words of the answer to look for hidden agendas, or interpret words differently from how they are presented.

On the continuum of high context and low contexts, Chinese are placed on the most extreme end of high context, and Westerners are pretty much at the other end of the scale. This gives us some inkling of the likelihood of effectiveness when Chinese communicate with Westerners.

With this in mind, miscommunication can easily occur. The large gap culturally between Westerners and Chinese may result in the communication going in the totally opposite direction to what was intended.

For instance, when Chinese negotiate in their wordy manner and do not express explicit meanings, Australians will be drawing conclusions from the words presented rather than looking for the hidden agendas and the meanings between the words. In the meantime, the Chinese will not believe that explicit words mean what they seem to mean but will be guessing the ‘real’ meanings. This will further increase the misunderstanding and heighten miscommunication.

Another difference between high context and low context cultures in communication style is that high context people (Chinese) express their ideas implicitly, using lots of implicit supporting evidence. Often, on the surface, this evidence does not appear to be directly related to the main topic. Chinese communicate using the popular approach of combining several philosophies and systems of logic (which can be culturally biased) throughout an explanation to demonstrate certain points. This may totally confuse Westerners who have the opposite style and logic.

Westerners communicate by stating results explicitly from the beginning and supporting them with evidence. This cultural group is seen as direct, sometimes blunt, especially by Chinese. Low context Westerners express their opinions and ideas without hesitation, expecting the receiver to reply and express their opinions through the feedback loop in the same manner. Ideas, opinions, suggestions and decisions may be refined through a series of communication processes.

This fundamental difference in approach makes communication between high context and low context cultures very difficult unless briefing and/or training is provided beforehand.

Context becomes even more important in understanding messages that have the potential to be distorted or omitted altogether. These distortions and omissions can only be noticed by people of a different culture in a communication process. This is because of the different cultural context. Listeners within the same culture are already ‘contextualised’, so do not need to be given much concrete background information. On the other hand, listeners from a different culture will need to be ‘contextualised’ first. This can be a lengthy process.

Understanding high context and low context culture also helps in understanding how people relate to each other, especially through social bonds, responsibility, commitment, social harmony and communication (Kim, Pan, and Park 1998). People of high context culture tend to be deeply involved with each other; in low context culture, people are highly individualised, somewhat alienated and fragmented, and there is relatively little involvement with others (Hall 1976). Chinese, who are collective and high context cultural people, behave in the most connected and relationship orientated manner, which is the very opposite to Westerners, who are low context individualists.

The communication pattern of people from a low context culture providing a high level of content and a low level of words, and high context people providing a high level of words but a low level of content, is the major reason that Chinese often regard Westerners as ‘silly’, because they give direct and precise information, leaving no room for guessing games. For people from a high context culture, it is not nearly complex enough.

As for the results of negotiations, high context negotiators gather more information during talks than low context negotiators. This serves as an astute strategy for high context negotiators to prepare for the later stages of the negotiation (Chung 2008).

A tough negotiation I was involved in relating to the Australian Retirement Living Group (ARLG) is a good example of how a mixture of high context and low context culture works in negotiation. The first visit the group made to China was to negotiate the possibility of collaboration or investments with a Chinese investment group in Changzhou. It was going to be tough because we knew the only competitor was a large US company with more than 300 retirement homes and investments in 50 countries. ARLG was a combination of an architecture firm, a retirement living group and a consultant from China.

Limitations in practical situations

There are limitations in applying the context concept to all cultures. First, to simply divide all cultures into high and low context means that at each spectrum a very wide range of different cultures is covered, which creates inaccuracy (Hall 1976). Second, in determining at which end of the spectrum a culture belongs, personal bias has a strong influence (Kim, Pan, and Park 1998). In other words, the determination of one individual by another of their position on the scale from high to low context is highly dependent upon the culture of the person making the judgement.

If that person is from a culture on the extreme end of the low context scale, they are likely to judge a high context person as being on the further end of the high context scale than the actual position on the scale; a low context person who is more towards the middle of the scale is likely to put the same person at the lower end of high context.

The measuring process is far too fluid to reach any definite conclusions. This eliminates accuracy in cross-cultural studies at the macro level. However, the question is posed as to whether one is ever able to determine the exact position on the scale of culture, because the concept is such a complex topic. Nevertheless, the concept of high context and low context culture provides the basis of understanding people of different cultures, and of not taking a situation for granted.

Miscommunication across cultures

The essence of communication is the exchange of information, with information being the carrier of meaning. Between different cultures, the perception of those sending the message may be totally different to the perception of their audience (Condon and Yousef 2002; Chaney and Martin 2004; Tian and Emery 2002). Therefore, identifying the audience and designing the message according to the perception of the audience, instead of that of the sender, before transmitting it, is a sound way of ensuring effective communication.

The complexity of communication processes determines that miscommunication always involves communication across cultures (Coupland, Wiemann, and Giles 1991). Cross-cultural communication relies deeply on the designing, transmitting and receiving of messages.

Understanding cultural differences is the basis of effective cross-cultural communication. ‘When communicators come from different backgrounds, the potential for misunderstandings is greater. Culture provides a perceptual filter that influences the way we interpret even the simplest event’ (Adler and Rodman 2000). Therefore for a cross-cultural communication process to be effective, the ability to translate the cultural context (Chung 2008) rather than just the words is essential.

Although knowledge and the study of cultural differences can reduce the ‘noise’ in communication processes and improve the effectiveness (Tse et al. 1988), without the successful translation of cultural context, miscommunication is inevitable. It is this requirement for successful translation at the cultural level that often cannot be achieved.

As mentioned, cultural differences determine the ways people behave, and hence communicate. In a Chinese-Westerner negotiation process, two groups often start by testing the communication methodologies until a mutually understood pattern is established. Where differences are greater between the parties, this pattern may never be established.

This process is fertile ground for misunderstandings, which are generally minor at the beginning. The real danger is when miscommunication is caused by cultural differences that neither party is aware of. In many cases the miscommunication continues without being detected until a major communication breakdown occurs. This is common in Western-Chinese negotiations because when Chinese are not clear about a message they are unlikely to initiate discussions to clarify the matter. The normal action for Chinese is to walk away for fear of causing conflict.

The Glass Wall Effect

The Glass Wall Effect relates to when people observe the behaviour of people of a foreign culture as if from the other side of a glass wall. They do not realise the barrier exists because they cannot see it. The barrier consists of prior knowledge or experience of the foreign culture that has created bias in understanding (Chung 2008).

The Glass Wall Effect as a concept addresses questions that were fundamental to my early research for this book. Does prior knowledge of, and training in, a culture create a situation where parties are under the false impression that all cross-cultural behaviour is understood, yet in reality it is found to be difficult to comprehend? Does such a phenomenon become an invisible barrier to cross-cultural communication?

In some cases prior knowledge or experience of a culture is misleading and unhelpful in dealing with cross-cultural situations. People may be caught in a situation where they cannot explain differences in behaviour. For example, knowledge in dealing with Japanese may give false confidence in dealing with Chinese, thinking that ‘Asian’ cultures are all the same, or similar. This is especially confusing when Asians of Chinese background present themselves as Chinese - an ethnic group, rather than a nationality group.

People who observe cross-cultural behaviour from the other side of the glass are the primary victims of the Glass Wall Effect. When they are placed in another new culture, their prior knowledge and experience of a previous different culture leads them to make little or no effort to adjust.

This concept may be extended to a false Glass Wall Effect; that is, when certain behaviour is the norm in one culture it is assumed the same behaviour is also the norm in another. For instance, in Japan, to appreciate tasty noodles, it is acceptable to slurp. Mistakenly, people with Japanese experience do the same in China, especially if they are exposed to very cheap street eating. In reality, slurping noodles is simply a sign of bad manners in Chinese culture, but it is often done by a large number of Chinese.

This is because until recently, 80 per cent of the Chinese population grew up in the countryside and had little education. A smaller percentage (50 to 60 per cent) of the population now lives in the countryside but a majority are still not tertiary educated. Further, Chinese mannerisms tend to be taught through family education rather than schooling. The false Glass Wall Effect can therefore be a bigger danger culturally because it is hidden and, without deep cultural awareness, will not be realised.

Foster’s Brewing expatriates with experience working at Foster’s Fiji before going to China in the 1990s repeatedly suggested that China was ‘easy’ when they first arrived. But it was soon recognised that China was very different to Fiji and many of them described the Chinese culture as ‘alien’. Their Fiji experience might have helped to create a Glass Wall Effect.

The Glass Wall Effect may also be seen in people working in a foreign culture who have had short-term cross-cultural training, say two weeks before departure, giving a false sense of security. A typical example: After a one-day training course I conducted, one participant commented, ‘Now I have learnt so much and I know doing business with Chinese is all just about trust and relationships.’ He quickly organised a trip to China to visit some business contacts. In all future negotiation sessions he would start by saying, ‘I know doing business in China is all based on trust and relationships . . .’ He was soon telling others that he knew all about doing business with Chinese, which was about trust and relationships, nothing else.

The Glass Wall Effect in practice – a deadly sin

With increasing business activities in China, more and more people are getting experience in visiting, working or studying in China. Many of these people are in danger of suffering from the Glass Wall Effect.

I was in a delegation where one member had spent about a year in China in the past. The problems were that he had spent most of his time with expats; and having a Westerner’s perspective, he thought he knew about China, whereas learning everything about China (if that is possible) would have taken many years of living, thinking and acting as a Chinese. He was unable to read the language and could speak only a few words, and could not pick up the non-verbals at a critical negotiation session.

Fortunately it was not a disaster because I was closely involved in the negotiation and interpretation. The negotiation session was tough as I was representing a small Australian company with one shareholder. I knew the competitor that had been negotiating with the Chinese company was a large established US firm with 20 years’ experience in the particular industry, and more than 300 facilities and investments in over 50 countries.

Strictly speaking, the Australian company was not even in a position to compete. However, I managed to turn the negotiation into a positive outcome using three main points:

1. The existing relationship, which was built over four years.

2. Emphasising my role as a bicultural person, and therefore the capacity of the company to be able to deliver a successful Australian model but with adaptation to the Chinese culture.

3. Although the Australian company was not able to compete on size, it was able to compete on quality.

The first point was communicated with few spoken words from either party. The second was largely discussed along the lines of communication and past examples of failed Western companies. The chief negotiator on the Chinese side was educated in Australia through Australian secondary and tertiary systems. She confided in me how hard she found communicating with Americans and Australians when I was not there. Because of her exposure to Western tertiary education, she was aware of the concept of cultural differences. She also specifically pointed out the endless examples of unsuccessful Western companies in China. She emphasised why they must have a Chinese model modified from an Australian model. They must not use a pure Australian model.

I use that example to argue that the Glass Wall Effect may lead to the most dangerous of all behaviour because it is not easily recognised and does not become obvious until damaging results appear. When this happens, relationships and trust are damaged, causing difficulties for future cooperation that might lead to permanent separation.

A Foster’s general manager with previous experience working in Taiwan was imbued with a false sense of security in managing mainland Chinese staff. Both the management and the executive fell into the trap of the Glass Wall Effect. The executive used his past knowledge from Taiwan in dealing with mainland Chinese, thinking there was just one Chinese culture.

Senior management were even more in the dark because they thought the executive’s language skills gained in Taiwan were just enough to manage the mainland Chinese employees. To the contrary, the mainland Chinese did not trust him because of his language skills, and kept information and knowledge away from him. His Taiwanese knowledge was totally out of place in mainland China.

He did not understand that Taiwan and mainland China differ dramatically in many aspects of culture, with the major cause of differences being the Cultural Revolution. The core concept of the Cultural Revolution was to eradicate traditional Chinese culture and to implement the Communist doctrine.

Mainland Chinese under the Communist regime gave up many traditional Chinese values that Taiwan maintained, and Taiwan Chinese have embraced many strong Western cultural, political and business influences through close association with America, in particular, since the Second World War. On the other hand, during the same period mainland China was totally closed to the West until a change in attitude began to emerge slowly about 30 years ago, accelerating in the 1990s.

The existence of the glass wall blinded the general manager who had been in Taiwan from accurately seeing mainland Chinese behaviour and prevented him from addressing issues accordingly. Equally, the company’s selection process of appointing personnel who spoke the language and had experience in Taiwan (or other geographically close Asian countries) was a result of the Glass Wall Effect. Of course, that was not the only selection criteria.

Assumptions that previous international experience will lead to success in China pose dangers because such individuals may not be capable of seeing China in a different way. It is natural for people to seek similarities between cultures to protect their comfort zones, but such perceptions and the use of stereotypes almost guarantee a poor result.

Common comments among those who have dealt with people of other cultures include ‘People are people’, ‘People are all the same’, ‘The Chinese are the same as us in business because they want profit and so do we’. Perhaps these comments appear to be reasonable on the macro level, but at the micro level they do not help. They create a Glass Wall Effect in cross-cultural communication.

Chairman Mao said: ‘A blank sheet of paper is better. Pictures can be drawn on it.’ People without prior knowledge are less likely to bury their heads in the sand and pretend they cannot see problems when they encounter them, and therefore there is less chance of a Glass Wall Effect occurring. The only way to overcome the problem is to clearly recognise the possible cause of such an effect and face any new culture without predetermined stereotypes.

Interpreters in cross-cultural communication

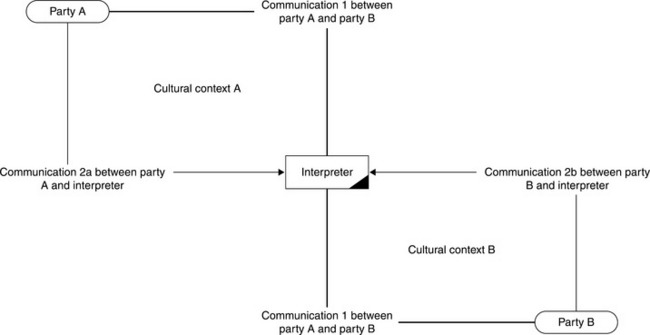

In communication processes with Chinese, interpreters are always used, but this in itself can be a major cause of misunderstanding. Figure 2.2 illustrates the situation when one interpreter is used for communication between party (A) of Western culture (A) and party (B) of Chinese culture (B).

Figure 2.2 Cross-cultural communication model between two parties of different cultures with the presence of one interpreter

To have to translate between English and Chinese means that one negotiation process is now composed of two communication processes where the interpreter is the core element of both processes. He or she controls the flow of information, accuracy of information and more importantly the accuracy of meanings being sent through each end of the parties. This is no doubt a challenge for any individual. Those with strong cultural understanding of both Western and Chinese business cultures are clearly going to achieve the set target better than those who do not. (This of course, assumes that the interpreter has a high level of language skills in both languages.)

It is common when Westerners arrive in China for negotiations that they are allocated, or locate, an interpreter locally. It is the most cost-effective method to overcome language barriers. However, when the interpreter has no or little understanding of Western culture, it is unlikely they will be able first to understand, and second, to translate the full and correct meaning of all messages. This is often ignored as people tend to use technical knowledge as the scapegoat because it is more obvious and tangible.

In addition, the interpreters are often provided by the Chinese party and most commonly are employees of that organisation. They have good understanding of their organisational culture, and working knowledge of their organisation, colleagues, and products. On the other hand, they know very little about the Western party and products.

A third problem is that Chinese are culturally bound not to tell anyone they do not understand. Therefore even when they encounter issues, phrases and words they do not understand, they will not acknowledge that or seek clarification for fear of losing face. Therefore, for Western negotiators, to engage an interpreter who has the full understanding of Western business culture is far more effective than using who is provided.

Fourth, an effective communication process with interpreters relies on both sets of communicators. People who are not exposed to working in different languages do not have the skills needed to work with interpreters. They often speak a paragraph before stopping to allow the interpreters to interpret. For inexperienced interpreters, or informal situations where interpreters do not, or do not have time to, write notes, translations cannot be complete. Points are often missed or misunderstood by other parties.

However, this will create the situation where two interpreters are used, as illustrated in Figure 2.3 when each party engages their own interpreters. This complicates the intended single communication process of the negotiation and turns it into three communication processes. Ideally, both interpreters have equal expertise of both cultures and language skills. The third process of communication between the two interpreters is where messages and meanings are clearly transferred between Westerners and Chinese. However, that circumstance is rare.

Figure 2.3 Cross-cultural communication model between two parties of different cultures with the presence of two interpreters

Differences in the expertise of individual interpreters engaged by Westerners and Chinese are unavoidable and therefore an imbalance in the spoken communication processes is likely to occur and miscommunication is equally inevitable. By understanding this, Western companies will also understand the importance of engaging good interpreters who have competent cultural knowledge of both Australia and China, on top of their competent English and Chinese language skills.

The previously mentioned differences in communication styles of high context and low context cultures, between Chinese and Westerners, are posing a barrier for speakers to achieve full awareness of the misunderstandings, which in turn leads to their failure to attain the goals of the negotiation (Coupland, Wiemann, and Giles 1991).

The importance of interpreters cannot be emphasised enough, because half-baked cultural knowledge or none at all and incompetent language skills of both English and Chinese, are likely to confuse issues rather than clarify them. Too often we hear ‘Chinese all speak English.’ Chinese all try to speak English, but very few speak good English with a sound understanding of Western business culture. They cannot understand the nuances and implications; hence they miss the real meaning covered by Western business people. These culturally branded phrases and terms flow with the language, consciously or not when used.

On a recent trip with an Australian delegation to China, one member of the other party had an Australian tertiary degree and citizenship. Theoretically speaking, she should be translating for the Chinese and I should be translating for the Australians. But because the company with which we were negotiating was known to me for many years, this formality was soon abandoned. Negotiations progressed positively, but we still stumbled on several miscommunications simply because the different Australian system could not be understood and there are no similar comparisons in the Chinese system.

When we finally concluded the negotiation positively and signed an agreement, my Chinese counterpart commented how important cross-cultural communication is and how my presence helped. She also commented on previous negotiations with a US firm, which was less successful despite having a Chinese person on its team.

Communication issues are constant in the process of conducting business with Chinese. Even after dealing with Chinese for some time, experienced Westerners will revert to their normal low context communication style at some stage subconsciously. This is inevitable because we are branded by the culture we grow up with. According to the latest neural research, we are hard-wired in the ways we communicate.

One long-term client of mine who has been to China many times with me and left much of the major negotiation to me, periodically expresses his disbelief at the Chinese partner’s behaviour: ‘I don’t understand what he is doing. It doesn’t make any sense.’ I found myself in the position of using expressions such as, ‘This is not what he meant’, ‘Please understand from his position as Chinese, or Australian’ to both sides constantly.

For another client, when the Chinese expressed their conscientiousness in projecting sales figures for the reason of implied responsibility (which is more cautious than Western businesses projection), the Australians interpreted that as ‘The Chinese are not willing to do a feasibility study’.

As a consultant, I need to be on high alert for these types of communication hurdles at all times. These situations re-occur sometimes on a daily basis.

References

Adler, R.B., Rodman, G.Understanding Human Communication. USA: Harcourt College Publishers, 2000.

Chaney, L.H., Martin, J.S.Intercultural Business Communication. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004.

Chung, M.Shanghaied: Why Foster’s Could Not Survive China. Melbourne: Heidelberg Press, 2008.

Condon, J.C., Yousef, F.S. Communication perspectives. In: Little S., Quintas P., Ray T., eds. Managing Knowledge. London: Sage Publications, 2002.

Coupland, N., Wiemann, J.M., Giles, H.Miscommunication and Problematic Talk. Newbury Park: Sage, 1991.

Dwyer, J.Communication in Business: Strategies and Skills. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Prentice Hall, 2002.

Hall, E.T.Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday & Company Inc, 1976.

Hall, E.T., Hall, M.R.Understanding Cultural Differences. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press, Inc, 1990.

Kennedy, J., Everest, A. Put diversity in context. The Secured Lender. 1996; 52:54.

Kim, D., Pan, Y., Park, H.S. High-versus low-context culture: a comparison of Chinese. Korean, and American cultures, Psychology and Marketing. 1998; 15:507–521.

Korac-Kakabadse, N., Kouzmin, A., Korac-Kakabadse, A., Savery, L. Low and high context communication patterns: towards mapping cross-cultural encounters. Cross Cultural Management. 2001; 8:3–24.

Tian, R.G., Emery, C. Cross-cultural issues in Internet marketing. Journal of American Academy of Business, Cambridge. 2002; 1:217–224.

Tse, D.K., Lee, K., Vertinsky, L., Wehrung, D.A. Does culture matter? A cross-cultural study of executives choice, decisiveness and risk adjustment in international marketing, Journal of Marketing. 1988; 52:81–95.