Coping With Political and Economic Risks

Overview

Diversification in global trading benefits international business investments, especially in emerging markets, which have become a prominent feature of the financial globalization sweeping the world over the last decade. Whether conducting business or investing in emerging markets, corporations and investors are always exposed to political environments that are not typically present in advanced economies.

The risk of major violence is greatest when high levels of stress combine with weak and illegitimate national institutions. Emerging nations are vulnerable when their institutions are unable to protect their citizens from abuse, or to provide equitable access to justice and economic opportunity. These vulnerabilities are exacerbated in countries with high youth unemployment, growing income inequality, and perceptible injustice. In addition, externally driven events such as infiltration by foreign combatants, the presence of trafficking networks, or economic shocks add to the stresses that can provoke violence.

According to the World Bank’s World Development Report 2011, about 1.5 billion people live in countries affected by repeated cycles of political and criminal violence, and no low-income fragile or conflict-affected country has yet to achieve a single Millennium Development Goal.* Fixing the economic, political, and security problems that disrupt development and trap fragile states in cycles of violence requires strengthening national institutions and improving governance in ways that prioritize citizen security, justice, and jobs.

Political and economic risks in emerging and frontier markets, apart from the very human cost of fragility, influence international business development, foreign trade, and foreign investors’ perceptions of risk, especially political risk, which affects private sector activity. This produces a vicious cycle, where these economies worsen, increasingly fragility, especially in frontier markets. By frontier markets we mean the type of country that is not yet a developed market. The term is an economic term coined by International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) Farida Khambata in 1992. The term is used commonly to describe the equity markets of the smaller and less accessible, but still “investable,” countries of the developing world. These countries were in the past emerging markets. For more in-depth information, please refer to our book, Comparing Emerging and Advanced Markets: Current Trends and Challenges, same publisher, which provides much more breadth and depth on the topic.

Coping with Risks

Over the past two decades, we have witnessed Russian default on its debt to foreigners in 1998, the Mexican peso crisis in 1994, and the Asian economic meltdown in 1997. While these risks are usually well known to major banks and multinational companies, and assessment techniques in these domains are relatively well developed, they tend not to be appropriate in assessing the geopolitical aspects associated with cross country correlations.

Political risks for foreign direct investments (FDI) are affected when difficult to anticipate discontinuities resulting from political change occur in the international business environment. Some example include the potential restrictions on the transfer of funds, products, technology and people, uncertainty about policies, regulations, governmental administrative procedures, and risks on control of capital such as discrimination against foreign firms, expropriation, forced local shareholding, and so on. Wars, revolutions, social upheavals, strikes, economic growth, inflation, and exchange rates should be figured into the political and economic risk assessment, as these instances can negatively impact local investments as well as FDI.

Recent Political Unrests

Slowing economies, oppressive regimes, and broad societal changes have contributed to political instability in emerging markets and other countries in recent years. Corporations and international business professionals with interests in such areas face the potential for political violence, terrorist attacks, resource nationalism, and expropriation actions that can jeopardize the safety and security of their people, assets, and supply chains.

Conducting business internationally, therefore, may offer many opportunities, but not without risks, especially political ones. There have been a myriad of events occurring around the world in the past three years, particularly among emerging economies, more notably the MENA region, as depicted in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Several political conflicts affected MENA economies in the past three years

The Arab Spring

The Arab Spring, a revolutionary wave of demonstrations and protests, riots, and civil wars in the Arab world, began in early December 2010. Its effects are still lingering. As of November 2013 rulers from this region have been forced from power, as in Tunisia,1 which took down the country’s long-time dictator, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. At the time, many were looking to it as a turning point for the Arab world, and rampant speculation begun about what it could mean for other countries toiling under Islamic dictatorships.

Many Arab Spring demonstrations have been met with violent responses from authorities, as well as from pro-government militias and counter-demonstrators. These attacks have been answered with violence from protestors in some cases. A major slogan of the demonstrators in the Arab world has been Ash-sha`b yurid isqat an-nizam (“the people want to bring down the regime”).2 Hence, at the same time Tunisia, Egypt and Libya were dealing with the consequences of the Arab Spring, civil uprisings were also breaking out in Bahrain and Syria, while several major protests continued to erupt in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, and Sudan.

Tunisia, Where the Arab Spring Began

The Arab Spring started in Tunisia. The country’s “Jasmine Revolution” was the first popular uprising to topple an established government in the Middle East and North Africa since the Iranian revolution of 1979. The revolution in Tunisia also was the spark that ignited and inspired other revolutions in the region.

The Arab Spring unfolded in three phases. First, on December 17, 2011, a young Tunisian street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, set himself on fire in hopelessness and to protest his treatment at the hands of the authorities. Demonstrations broke out in his rural hometown followed by protests in other areas of the country. A brutal security crackdown followed, reported in chocking details by online social media. Second, when protests reached the capital, Tunis, the government responded with even more brutality, arresting demonstrators, activists, and shutting down the Internet. Lastly, President Zine el-Abedin Ben Ali shuffled his cabinet and promised to create 300,000 jobs, but it was too late; protesters now just wanted the regime to fall and its President stripped of any power. On January 14, Ben Ali and his family fled the country taking refuge in Saudi Arabia. This act marked the end of one of the Arab world’s most repressive regimes. It was a victory for people power and perhaps the first time ever in history that an Arab dictator has been removed by a revolution rather than a coup d’Etat.

Egypt

Although the Arab Spring began in Tunisia, the decisive moment that changed the Arab region forever was the downfall of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, ensconced in power since 1980. Similar to Tunisia, mass protests started in late January of 2011 and by early February, Mubarak was forced to resign after the military refused to intervene against the masses occupying Tahrir Square in Cairo.

Deep divisions emerged over the new political system as Islamists from the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) won the parliamentary and presidential election in 2011 and 2012, thus souring relations with secular parties who continued protests for deeper political change. The Egyptian military remains the single most powerful political player, and much of the old regime remains in place. The economy has been in decline since the start of unrest.3 By the time Mubarak resigned, large portions of the Middle East were already in turmoil. While the Egyptian people succeeded in overthrowing Mubarak from power, the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) continues to run the country in a transition period marked by violence and instability.

At the time of these writings, June 2014, a veteran politician, Ibrahim Mahlab, who was serving as Egypt’s interim prime minister. He was sworn in as the head of a new cabinet by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in the president’s first major decision since his election victory in May 2014. Sisi has promised to restore security and the country’s struggling economy at the top of his agenda, and has pledged to build a more stable future after three turbulent years since the toppling of longtime ruler Hosni Mubarak.

Libya

Soon after Mubarak’s resignation, in February 2011, protests against Col. Muammar al-Qaddafi’s regime in Libya started in front of Benghazi’s police headquarters following the arrest of a human rights attorney who represented the “relatives of more than 1,000 prisoners allegedly massacred by security forces in Tripoli’s Abu Salim jail in 1996,” which escalated into the first civil war caused by the Arab Spring.

What began as a series of peaceful demonstrations turned into confrontations, which were met with military force. When the National Conference for the Libyan Opposition organized a “Day of Rage” (February 17, 2011), the Libyan military and security forces did not allowed the demonstration to go on and fired live ammunition on protesters. The following day, security forces withdrew from Benghazi after being overwhelmed by protesters, while some security personnel also joined the protesters. The protests spread across the country and anti-Gaddafi forces established a provisional government based in Benghazi, called the National Transitional Council with the stated goal to overthrow the Gaddafi government in Tripoli.

NATO† forces had to intervene in March 2011 against Qaddafi’s army helping the opposition rebel movement capture most of the country by August 2011. In October 2011 Qaddafi was killed, but the rebels’ coup was short-lived, as various rebel militias effectively partitioned the country among them, leaving a weak central government that continues to struggle to exert its authority and provide basic services to its citizens. Most of the oil production has returned on stream, but political violence remains endemic, and religious extremism has been on the rise.4

Yemen

Even before the Arab Spring from Tunisia and Egypt reached Yemen, President Saleh’s regime faced daunting challenges. In the north, it was battling the Huthi rebellion. In the south it faced an ever-growing secessionist movement. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula was showing mounting signs of activism. Sanaa’s political class was locked in a two-year battle over electoral and constitutional reforms while behind the scenes a fierce competition for post-Saleh spoils was underway. Economic conditions for the average Yemenis were dismal and worsening.

Bolstered by events in Tunisia, anti-government protesters of all political parties started pouring onto the streets in mid-January 2011. Hundreds of people died in clashes as pro-government forces organized rival rallies, and the army began to disintegrate into two political camps.

Largely caught off guard, the regime’s response was mixed. It employed harsh tactics, particularly in the south, arresting, beating, harassing, and even killing activists. By most accounts, regime supporters donning civilian clothes took the lead, wielding sticks, clubs, knives, and guns to disperse demonstrations. Police and security personnel at best failed to protect protesters, at worst encouraged or even participated in the repression. On March 8, 2011 the army used live ammunition against demonstrators and represented a worrisome escalation.

Still, Yemen was neither Egypt nor Tunisia. Notwithstanding, Egypt was not like Tunisia, which says something about how oblivious popular protests are to societal differences and how idle speculations can be regarding what a regime might do next. Yemen’s regime was less repressive, more broadly inclusive and adaptable. It appeared to have perfected the art of co-opting its opposition, and as a result, the extensive patronage network discouraged many from directly challenging the president. Moreover, flawed as they are, the country had, and still has, working institutions, including a multi-party system, a parliament, and local government.

Nonetheless, the protesters, with the wind at their backs, expected nothing less than the president’s quick ouster. The president and those who have long benefited from his rule were not willing to give in without a fight. Finding a compromise was nearly impossible as the regime would have to make significant concessions, indeed far more extensive than it so far had been willing to do. To be meaningful, these concessions would have to have touched the core of a political system that had relied on patron-client networks and on the military-security apparatus. Besides, a democratic transition was long overdue.

As a result, in the end, the Yemeni leader Ali Abdullah Saleh became the fourth victim of the Arab Spring. Amidst this turmoil, Al Qaeda in Yemen began to seize territory in the south of the country. Had it not been for Saudi Arabia’s facilitation of a political settlement Yemen would have fallen victim to an all-out civil war. President Saleh signed the transition deal on November 23, 2011, agreeing to step aside for a transitional government led by the Vice-President Abd al-Rab Mansur al-Hadi. However, little progress toward a stable democratic order has been made and regular Al Qaeda attacks, separatism in the south, tribal disputes, and a collapsing economy are all stalling this nascent transition.5

Protests in Bahrain

Protests in Bahrain began on February 2012, just days after Mubarak’s resignation. Bahrain has always had a long history of tension between the ruling Sunni royal family, and the majority Shiite population demanding greater political and economic rights. The Arab Spring acted as a catalyst, reenergizing the largely Shiite protest movement, driving tens of thousands to the streets defying fire from security forces. The Bahraini royal family was saved by a military intervention of neighboring countries led by Saudi Arabia. A political solution, however, was not reached and the crackdown failed to suppress the protest movement. As of early fall 2013, protests, clashes with security forces, and arrests of opposition activists continue in that country with no solution in sight.6

More recently (March 2014), tensions between Qatar and neighboring Persian Gulf monarchies broke out when Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors from the country over its support of the Muslim Brotherhood‡ and allied Islamists around the region. The concerted effort to isolate Qatar, a tiny, petroleum-rich peninsula, was an extraordinary rebuke of its strategy of aligning with moderate Islamists in the hope of extending its influence amid the Arab Spring revolts.

But in recent months Islamists’ gains have been rolled back, with the military takeover in Egypt, the governing party shaken in Turkey, chaos in Libya, and military gains by the government in Syria. The other gulf monarchies always had bridled at Qatar’s tactic, viewing popular demands for democracy and political Islam as dual threats to their power.

The Saudi monarchs, in particular, have grumbled for years as tiny Qatar has swaggered around like a heavyweight. It used its huge wealth and Al Jazeera, which it owns, as instruments of regional power. It negotiated a peace deal in Lebanon, supported Palestinian militants in Gaza, shipped weapons to rebels in Libya and Syria, and gave refuge to exiled leaders of Egypt’s Brotherhood; all while certain its own security was assured by the presence of a major American military base.

Conflicts in Syria

Syria, a multi-religious country allied with Iran, ruled by a repressive republican regime, and amid a pivotal geo-political position was next. The major protests began in March 2011 in provincial towns at first, but gradually spreading to all major urban areas. The regime’s brutality provoked an armed response from the opposition, and by mid-2011 Army defectors began organizing in the Free Syrian Army.

Consequently, by the end of 2011, Syria descended into civil war as rebel brigades battled government forces for control of cities, towns, and the countryside. Fighting reached the capital Damascus and second city of Aleppo in 2012. This war is still ongoing today, with most of the Alawite§ religious minority siding with President Bashar al-Assad, and most of the Sunni majority supporting the rebels. Both camps have outside backers. Russia supports the regime. Saudi Arabia supports the rebels. Neither side is able to break the deadlock.7

The armed rebellion has evolved significantly, with as many as 1,000 groups commanding an estimated 100,000 fighters. Secular moderates are outnumbered by Islamists and jihadists linked to al-Qaeda, whose brutal tactics have caused widespread concern and triggered rebel infighting. Although investigators have been denied entry into Syria and their communications with witnesses have been restricted, investigators have confirmed at least 27 incidents of intentional mass killings.

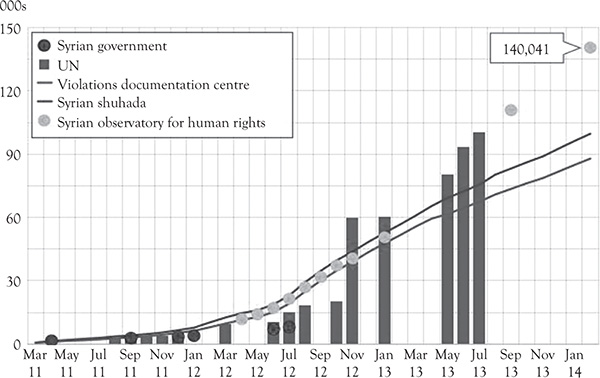

In July 2013, as depicted in Figure 3.2, the UN said more than 100,000 people had been killed. It has stopped updating the death toll, but activists say it now exceeds 140,000. According to BBC,¶ a UN commission of inquiry has been investigating all alleged violations of international human rights law since March 2011. It has evidence showing that both sides have committed war crimes including torture, hostage taking, murder, and execution. The commission argues that 17 of these war crimes were perpetrated by government forces and pro-government militia, including incidents that left hundreds of civilians dead in Houla in May 2012 and Baniyas in August 2013. Rebel groups have been blamed for 10 massacres, including the slaughter of at least 190 people in the Latakia countryside in August 2013 by jihadist and hardline Islamist fighters.

Figure 3.2 Syrian casualties since the start of the civil war

Source: UN

Conflicts in Morocco

On February 20, 2011, the Arab Spring engulfed Morocco, when thousands of protesters gathered in the capital city of Rabat. They demanded greater social justice and limits to King Mohammed VI’s power. The king responded by offering constitutional amendments ceding some of his powers, and by calling a fresh parliamentary election that was controlled less by the royal court than in previous elections.

The message of a democratic agenda and gradual change was one that has gone down well with Morocco’s allies in the United States and Europe. We believe the Arab World is in the process of changing. It is still too soon to prognostic the results of which political and socioeconomic direction Egypt, Tunisia, Syria, or Yemen will take. We also believe that if there is a country impacted by the Arab Spring that may become an example on how to bring about a gentle revolution that could eventually become a real democracy, that is Morocco. How long it will take and if it ever will happen is anyone’s guess, as the reforms passed in 2011 are still largely cosmetic and there is no guarantee they will be put into practice on the ground.

The king retains ultimate control and though parliament has more power, the political parties are weak. These reforms, coupled with fresh state funds to help low-income families, diminished the appeal of the protest movement, with many Moroccans content with the king’s program of gradual reform. Rallies demanding a genuine constitutional monarchy continue, but have so far failed to mobilize the masses as it did in Tunisia and Egypt.8

Demonstrations in Jordan

Demonstrations in Jordan gained momentum in late January 2011, as Islamists, leftist groups and youth activists protested against living conditions and corruption. Parallel to Morocco, most Jordanians wanted reform, rather than abolish the monarchy, giving King Abdullah II the breathing space his republican counterparts in other Arab countries didn’t have. Consequently, the king managed to ease the Arab Spring by making superficial changes to the political system and reorganizing the government. Fear of chaos similar to Syria did the rest. To date, the economy, however, is still performing poorly and none of the key issues have been addressed, which may prompt protesters’ demands to grow more radical over time.9

Jordan’s version of the Arab Spring may have been over quietly and unceremoniously, but regional upheavals, especially in Syria and Egypt, have dampened Jordanians’ appetite for drastic change in their own country. Back in 2012, tens of anti-government protests took place in Jordan, especially on Fridays. The Muslim Brotherhood organized most of them, but the Jordanian Youth Movement, or hirak, whose slogans often crossed red lines, led some. They called for regime change and accused King Abdullah II of corruption. Many of their leaders are now in prison and some will stand trial in front of the State Security Court (SSC) on charges that range from insulting the king to attempting to overthrow the regime.

Although it has been a few years since the large demonstrations were held in Amman or elsewhere, back in November 2012, when the newly appointed government of Abdullah Ensour floated the price of gasoline and ended state subsidies, thousands took to the streets and the country saw three days of angry demonstrations and clashes with the police. The opposition, an alliance between the Islamists and a coalition of leftist and nationalist groups and parties called the National Reform Front (NRF), threatened to further derail austerity measures. When the government raised the price of electricity last month nothing happened. It was a sign that neither the Islamists nor the rest of the opposition were able to mobilize the street anymore.

Despite worsening economic conditions Jordanians became wary of instability and chaos that gripped neighboring Syria and Egypt, and indeed, most Arab Spring countries. Stability and security became more important than pressing for immediate political reforms. A growing number of Jordanians became suspicious of the Muslim Brotherhood agenda for Jordan. In fact, the alliance between the Islamists and NRF quickly unraveled when a prominent Brotherhood leader insisted that the goal of the movement was to establish a Sharia-led Islamic state in Jordan.

Regional changes have allowed the regime to recalibrate its position on issues. King Abdullah successfully weathered the storm by avoiding the use of violence and presenting himself as a champion of reforms. In 2012, he introduced important constitutional amendments and created a constitutional court. He published a number of papers on his vision for a democratic transition. While the controversial elections law was altered slightly, he organized legislative elections in early 2013 and introduced the first parliamentary government, which he said should remain in office for the entire term of the four-year Lower House.

We believe, however, that it may be too soon to assume the Jordanian’s Arab Spring is over. Economic challenges remain dire even as Gulf countries and the United States continue to pump money into Jordan’s coffers. Unemployment and poverty rates are still very high and the country has seen the worst episodes of societal violence in decades. As of spring of 2014, more than half a million Syrian refugees in Jordan have added unexpected burdens on the local economy. Political life has stagnated and people’s approval of parliament has plummeted. A recent incident when a Kalashnikov**-toting deputy tried to kill a colleague has renewed debate about the need to amend the election law and breathe life into political parties.

Furthermore, the Jordanian government is still unpopular, and unless economic life improves soon, we believe Jordanians may go back to the street in protest. The majority of protests that take place these days are economic in nature. In addition, the king has evaded substantial political reforms that relate to the complex issues of Jordanian identity and his own prerogatives as monarch; a major challenge in a country where at least half of its citizens are of Palestinian origin. The vital question now is how long can he ignore such issues?

So far he has been able to prove that Jordan is the exception to the rule in the Arab Spring saga, a similar situation experienced by Morocco. Jordan has avoided a repetition of the Egyptian or Syrian scenarios. The king has overcome popular protests and was able to repulse Muslim Brotherhood pressures. Jordanians are in no mood to take to the streets now, but that situation could change at any time.

Algeria

Algerian protests, which started in late December 2010, were inspired by similar protests across the MENA region. Causes cited include unemployment, the lack of housing, food-price inflation, corruption, restrictions on freedom of speech, and poor living conditions. While localized protests were already commonplace over previous years, extending into December 2010, an unprecedented wave of simultaneous protests and riots sparked by sudden rises in staple food prices erupted all over the country beginning in January 2011.

These protests were suppressed by government swiftly lowering food prices, but were followed by a wave of self-immolations, most of which occurred in front of government buildings. Despite being illegal to do so without government permission, opposition parties, unions and human rights groups began holding weekly demonstrations. The government’s reaction was swift repression of these demonstrations.10

In our research, we found that many nationals who experienced the Arab Spring would have preferred it never happened. Think of the mayhem that would have been avoided in Egypt and Syria, not to mention Libya, Yemen, and Bahrain, where the angry and the aggrieved have created chaos in the name of democracy. How foolish of advanced economies of the West, especially the United States and UK to turn on allies like Hosni Mubarak, and to pander to the Muslim Brotherhood, while assorting to narrow-minded Islamists. Unless of course, it was done on purpose.

Iraq

The 2011 Iraqi protests came in the wake of the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. The protests resulted in at least 45 deaths, including at least 29 on the Day of Rage, which took place on February 25, 2011. Several of the protests in March 2011, however, were against the Saudi-led intervention in Bahrain.11

Protests also took place in Iraqi Kurdistan, an autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq’s north that lasted for 62 consecutive days. More recently, on December 21, 2012, a group raided Sunni Finance Minister Rafi al-Issawi’s home and resulted in the arrest of 10 of his bodyguards.12 Beginning in Fallujah, the protests have since spread throughout Sunni Arab parts of Iraq, and have even gained support from non-Sunni Iraqi politicians, such as Muqtada al-Sadr. Pro-Maliki protests have taken place throughout southern Iraq, where there is a Shia Arab majority. In April 2013, sectarian violence escalated after the 2013 Hawija clashes.13

Kuwait

Kuwaiti protests took place in 2011–2012, also calling for government reforms. On November 28, 2011, the government of Kuwait resigned in response to the protests, making Kuwait one of several countries affected by the Arab Spring to experience major governmental changes due to unrest.14

In early April 2014, however, Kuwait’s once-feisty opposition appeared waning. Protests that in 2012 brought tens of thousands to the streets to call for reform had fizzled out while personality conflicts splintered a broad coalition of youth, Islamists, leftists, and tribal figures. Pundits declared Kuwait’s never-quite-Arab spring a bust.

But the public waning act masked what may be the most intense scheming in Kuwait in a decade. On April 12, 2014, Kuwait’s opposition re-emerged with a new website, politburo, media operation, and most importantly, demand for full parliamentary democracy. It is the most ambitious reform recently proposed in the Gulf, where Kuwait is the most democratic of all the monarchies.

The call for change is likely to send jitters across the rest of the Gulf, where Kuwait is used as a symbol of why democracy is a bad idea. Fighting between Kuwait’s parliament and cabinet (the latter is named by the emir) have held up key infrastructure projects, caused instability, and diminished public confidence. But if Kuwait can surmount those obstacles and gives its people a greater say in their country, it will become a source of fear.

Sudan

As part of the Arab Spring, protests in Sudan began in January 2011 with a regional protest movement. Unlike other Arab countries, however, popular uprisings in Sudan succeeded in toppling the government prior to the Arab Spring, in both 1964 and 1985. Demonstrations were less common throughout the summer of 2011, during which time South Sudan seceded from Sudan. It resumed in force in June 2012 shortly after the government passed its much criticized austerity plan.15

The Sudanese government, however, has absorbed the second shock triggered by its decision to remove fuel subsidies. This shock was even more violent than the first that hit the country in 2012. Yet Sudan is likely to face a third shock in 2014, which may be as violent and bloody as the recent wave of protests. This will occur when the government completely lifts fuel subsidies, which will increase the prices of many goods and services directly or indirectly associated with fuel. This step will present additional burdens for Sudanese citizens, who are already suffering from low purchasing power.

The government may have dodged the bullet of an Arab Spring that nearly ravaged Sudan, a country already dealing with several separate insurgencies in Darfur (in the west) and in the two border states of Blue Nile and South Kordofan (in the south). Still, the social situation of Sudanese citizens remains harsh and unenviable.

Other Countries Impacted by the Arab Spring

There have been other minor protests, which broke out in Mauritania, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, and West Sahara. In Mauritania,16 the protests were largely peaceful, demanding President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz to institute political, economic, and legal reforms. The common themes of these protests included slavery, which officially is illegal in Mauritania but is widespread in the country,17 and other human rights abuses the opposition has accused the government of perpetrating.

These protests started in January 2011 and continued well into 2012. In Oman18 demonstrations were demanding salary increases, increased job creation and fighting corruption. The sultan’s responses included dismissal of one third of his government cabinet.19 In Saudi Arabia20 the protests started with a self-immolation in Samtah and demonstration in the streets of Jeddah in late January 2011. It then was followed by protests against anti-Shia discrimination in February and early March of the same year in Qatif, Hofuf, al-Awamiyah, and Riyadh. In Djibouti21 the protests, which showed a clear support of the Arab Spring, ended quickly after mass arrests and exclusion of international observers. Lastly, in Western Sahara22 the protests were a reaction to the failure of police to prevent anti-Sahrawi looting in the city of Dakhla, Western Sahara, and mushroomed into protests across the territory. They were related to the Gdeim Izik protest camp in Western Sahara established the previous fall, which resulted in violence between Sahrawi activists and Moroccan security forces and supporters.

Still, there were still other related events outside of the region. In April 2011,23 also known among protesters as the Ahvaz Day of Rage, protests occurred in Iranian Khuzestan by the Arab minority. These violent protests erupted on April 15, 2011, marking the anniversary of the 2005 Ahvaz unrest. These protests lasted for four days and resulted in about a dozen protesters killed and many more wounded and arrested. Israel also experienced its share of political conflicts with border clashes in May 2011,24 to commemorate what the Palestinians observe as Nakba Day. During the demonstrations, various groups of people attempted to approach or breach Israel’s borders from the Palestinian-controlled territory, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, and Jordan.

Risks related to political instability cannot be eliminated completely, but multinational businesses can take steps to limit the potential effects on their operations. Therefore, before instability develops, businesses should have well-tested business continuity and crisis management plans in place. Organizations should identify their essential functions and assess the potential impact of unrest in various countries, taking into consideration customers, employees, and other key stakeholders.

Assessing Political Risks

As barriers to international trade easel, the dynamic global marketplace continues to attract investors who are eager to capitalize on opportunities they see in emerging markets around the world. Compared to a quarter century ago, these markets enjoy greater stability and are experiencing steady growth. However, these emerging markets remain vulnerable to a host of forces known as political risk that are largely beyond the control of investors. Among these risk factors are currency instability, corruption, weak government institutions, unreformed financial systems, patchy legal and regulatory regimes, and restrictive labor markets.

Multinational corporations and international business professionals can be affected by political risk even when their own operations are in less volatile regions. For instance, supply chains can be impacted, making it critical for businesses to ensure that their suppliers and other partners have robust risk management plans, while simultaneously making alternative suppliers part of resiliency planning.

To help protect personnel, operations, and assets, multinational corporations should consider taking proactive steps by:

• Providing personnel and business partners with regular updates about local government travel advisories.

• Monitoring airlines’ flight schedules and status.

• Maintaining up-to-date locations and travel plans for all employees and enabling them to report their status.

• Communicating with staff in affected countries to gain advice or provide information about changes to their situation.

The last bullet, communication, is a very important aspect for proactively dealing with risks at a foreign country. In a crisis, communication is crucial but could be hampered by government interference, damage to communications networks, loss of power, or other factors. In our consulting work, we always advise out clients to consider local conditions before traveling or sending their personnel abroad, including the use of technology (satellite phones, alternative currency, safe house, international insurance and evacuation services, such as International S.O.S,†† etc.). Companies and professionals operating in risky international regions should maintain current and complete contact information for employees, including personal e-mail addresses and mobile numbers, so that they can be reached through as many channels as possible. If appropriate, organizations also should consider the use of satellite phones or other technologies that may be more reliable during a crisis.

Corporations also should maintain frequent contact with local embassies, consulates, and other government representatives, which may be able to assist their nationals with communications or evacuations in a crisis. Prior to an event, businesses should have employee citizenship information, including passports, visas, and other travel documents on hand.

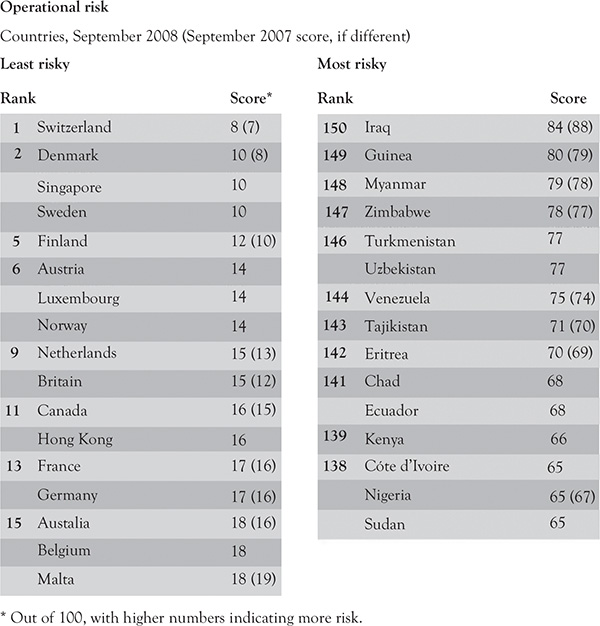

Assessment techniques for political risk are as wide-ranging as the sources that generate it. Traditional methods for assessing political risk range from the comparative techniques of rating and mapping systems, as depicted in Figure 3.3, to the analytical techniques of special reports, dynamic segmentation, expert systems, and probability determination to the econometric techniques of model building and discriminant and logit analysis.‡‡ These techniques are very useful for identifying and analyzing individual sources of political risk but aren’t sophisticated enough to handle cross relationships or correlations well. They also are not accurate measurements of levels of loss generated by the risks being analyzed. Hence, it is difficult to evaluate country profiling and analysis into a practical decision making tool.

Figure 3.3 Sample of a country profiling assessment matrix

In Dr. Goncalves’ lectures at Nichols College, when analyzing the inter-dynamics of advanced economies and emerging markets, two approaches are used for incorporating political risk in the capital budgeting process for foreign direct investments. The first approach involves an ad hoc adjustment of the discount rate to account for losses due to political risk, while the second approach involves an ad hoc adjustment of the project’s expected future cash flows and expected return on investment (ROI).

No company, domestic or international, large or small, can conduct business abroad without considering the influence of the political environment in which it will operate. One of the most undeniable and crucial realities of international business is that both host and home governments are integral partners. A government controls and restricts a company’s activities by encouraging and offering support or by discouraging and restricting its activities contingent upon the whim of the government.

International law recognizes the sovereign right of a nation to grant or withhold permission to do business at the privileges of the government. In addition, international law recognizes the sovereign right of a nation to grant or withhold permission to do business within its political boundaries and to control where its citizens conduct business.

In the context of international law, a sovereign state is independent and free from all external control; enjoys full legal equality with other states; governs its own territory; selects its own political, economic, and social systems; and has the power to enter into agreements with other nations. Sovereignty refers to both the powers exercised by a state in relation to other countries and the supreme powers exercised over its own members. A state outlines and decides the requirements for citizenship, defines geographical boundaries, and controls trade and the movement of people and goods across its borders.

Nations can and do abridge specific aspects of their sovereign rights in order to coexist with other nations. The European Union, UN, NAFTA, NATO, and WTO represent examples of nations voluntarily agreeing to succumb some of their sovereign rights in order to participate with member nations for a common, mutually beneficial goal. However, U.S. involvement in international political affiliations is surprisingly low. For example, the WTO is considered by some as the biggest threat, thus far to national sovereignty. Adherence to the WTO inevitably means loss to some degree of national sovereignty because member nations have pledged to abide by international covenants and arbitration procedures. Sovereignty was one of the primary issues at the core of a kerfuffle between the United States and the EU over Europe’s refusal to lower tariffs and quotas on bananas. Critics of the free trade agreements with both South Korea and Peru claim America’s sacrifice of sovereignty goes too far.

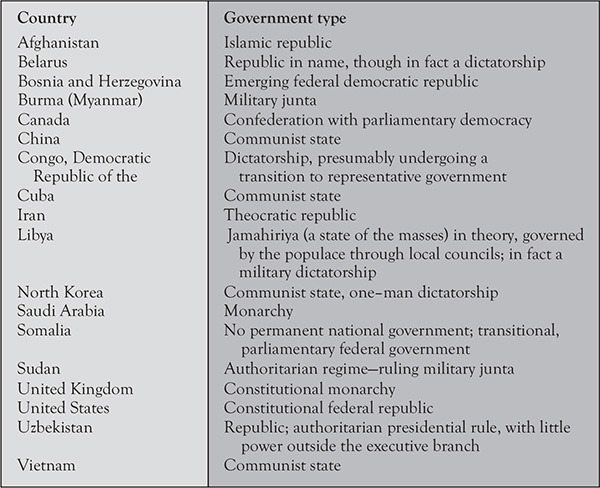

Figure 3.4 provides a sampling of countries electing other options including authoritarianism, theocracy, dictatorship, and communism, which are taking a different approach. Troubling is the apparent regression of some countries toward autocracy and away from democracy, such as Nigeria, Kenya, Bangladesh, Venezuela, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan. It is transparent for all to witness the world’s greatest experiment in political and economic change: the race between Russian reforms and Chinese gradualism as communism is further left behind in both countries.

Figure 3.4 A sampling of government types

Economic and cultural nationalism, which exists to some degree within all countries, is another important risk factor when assessing the international business environment. Nationalism can best be described as an intense feeling of national pride and unity. One of the economic nationalism’s central aims is the preservation of economic autonomy whereby residents identify their interests with that preservation of the sovereignty. Hence, national interests and security become far more important than international business relations.

Generally, the more a country feels threatened by some outside force or a decline in domestic economy is evident, the more nationalistic it becomes in protecting itself against intrusions. By the late 1980s, militant nationalism had subsided. Today, the foreign investor, once feared as a dominant tyrant threatening economic development, is often sought after as a source of needed capital investment. Nationalism vacillates as conditions and attitudes change, and foreign companies welcomed today may be harassed tomorrow.

It is important for international business professionals not to confuse nationalism, whose animosity is directed generally toward all foreign countries, with a widespread fear directed at a particular country. Toyota committed this mistake in the United States during the late 1980s and early 1990s. At the time Americans considered the economic threat from Japan greater than the military threat from the Soviet Union. So when Toyota spent millions on an advertising campaign showing Toyotas being made by Americans in a plant in Kentucky, it exacerbated the fear that the Japanese were “colonizing” the United States. The same sentiments ring true with China, who some believe, is colonizing the United States.25

The United States is not immune to these same types of directed negativity. The rift between France and the United States over the Iraq/U.S. war led to hard feelings on both sides and an American backlash against French wine, French cheese, and even products Americans thought were French. French’s mustard felt compelled to issue a press release stating that it was an American company founded by an American named French. Thus, it is quite clear that no nation-state, however secure, will tolerate penetration by a foreign company into its market and economy if it perceives a social, cultural, economic, or political threat to its well-being.

Various types of political risks should be considered before deciding to expand businesses or invest in foreign markets, for both advanced and emerging economies, but in particularly for frontier markets. The most severe political risk is confiscation, that is, the seizing of a company’s assets without payment. The two most notable recent confiscations of U.S. property occurred when Fidel Castro became the leader in Cuba and later when the Shah of Iran was overthrown. Confiscation was most prevalent in the 1950s and 1960s when many underdeveloped countries saw confiscation, albeit ineffective, as a means of economic growth.

Less drastic, but still severe, is expropriation, when the government seizes an investment but some reimbursement for the assets is made. Often the expropriated investment is nationalized, that is, it becomes a government-run entity. An example is Bolivia, where the president, Ivo Morales, confiscated Red Eletrica, a utility company from Spain.

A third type of risk is domestication. This occurs when host countries gradually induce the transfer of foreign investments to national control and ownership through a series of government decrees by mandating local ownership and greater national involvement in a company’s management. Figure 3.5 provides a sample list of country rankings in terms of political risks when operating a business.

Figure 3.5 Country ranking by political and operating risks

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit

Even though expropriation and confiscation are waning, international companies are still confronted with a variety of economic risks that can occur with little warning. Restraints on business activity may be imposed under the banner of national security to protect an infant industry, to conserve scarce foreign exchange, to raise revenue, or to retaliate against unfair trade practices. Following are important and recurring reality of economic risks, and recurring of the international political environment, that few international companies can avoid:

• Exchange control: These stem from shortages of foreign exchange held by a country.

• Import restrictions: These are selective restrictions on the import of raw materials, machines, and spare parts; fairly common strategies to force foreign industry to purchase more supplies within the host country and thereby create markets for local industry.

• Labor problems: In many countries, labor unions have strong government support that they use effectively in obtaining special concessions from business. Layoffs may be forbidden, profits may have to be shared, and an extraordinary number of services may have to be provided.

• Local-content laws: In addition to restricting imports of essential supplies to force local purchase, countries often require a portion of any product sold within the country to have local content, that is, to contain locally made parts.

• Price controls: Essential products that command considerable public interest, such as pharmaceuticals, food, gasoline, and cars, are often subjected to price controls. Such controls applied during inflationary periods can be used to control the cost of living. They also may be used to force foreign companies to sell equity to local interests. A side effect could be slowing or even halting capital investment.

• Tax controls: Taxes must be classified as a political risk when used as a means of controlling foreign investments. In such cases, they are raised without warning and in violation of formal agreements.

Boycotting is another risk, whereby one or a group of nations might impose it on another, using political sanctions, which effectively stop trade between the countries. The United States has come under criticism for its demand for continued sanctions against Cuba and its threats of future sanctions against countries that violate human rights issues. History, however, indicates that sanctions are almost always unsuccessful in reaching desired goals, particularly when other nations’ traders ignore them.

International business professionals traveling to emerging markets or even, to the so called least develop countries (LDCs), must be aware of any travel warnings related to political, health, or terrorism risks. The U.S. Department of State (DOS) provides country specific information for every country. For each country, there is information related to location of the U.S. embassy or consular offices in that country, whether a visa is necessary, crime and security information, health and medical conditions, drug penalties, and localized hot spots. This is an invaluable resource when assessing country risks.

The DOS also issue travel alerts for short-term events important for travelers when planning a trip abroad. Issuing a travel alert might include an election season that is bound to have many strikes, demonstrations, disturbances; a health alert like an outbreak of H1N1; or evidence of an elevated risk of terrorist attacks. When these short-term events conclude, the DOS cancels the alert.

During early summer 2014, the DOS issued a Worldwide Caution§§ to update information on the continuing threat of terrorist actions and violence throughout the world. The report recommended travelers to maintain a high level of vigilance and to take appropriate steps to increase their security awareness, as the Department was concerned about the continued threat of terrorist attacks, demonstrations, and other violent actions. According to the report, kidnappings and hostage events involving U.S. citizens have become increasingly prevalent as al-Qa’ida and its affiliates have increased attempts to finance their operations through kidnapping for ransom operations. Al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and al-Qa’ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) are particularly effective with kidnapping for ransom and are using ransom money to fund the range of their activities.

Kidnapping targets are usually Western citizens from governments or third parties that have established a pattern of paying ransoms for the release of individuals in custody. The DOS report also suggested that al- Qa’ida, its affiliated organizations, and other terrorist groups continue to plan and encourage kidnappings of U.S. citizens and Westerners. The Report also suggested that al-Qa’ida and its affiliated organizations continue to plan terrorist attacks against U.S. interests in multiple regions, including Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. These attacks typically employ a wide variety of tactics including suicide operations, assassinations, kidnappings, hijackings, and bombings. But such extremists can also elect to use conventional or non-conventional weapons, and target both official and private interests. Examples of such targets include high-profile sporting events, residential areas, business offices, hotels, clubs, restaurants, places of worship, schools, public areas, shopping malls, and other tourist destinations both in the United States and abroad where U.S. citizens and Westerns gather in large numbers, including during holidays.

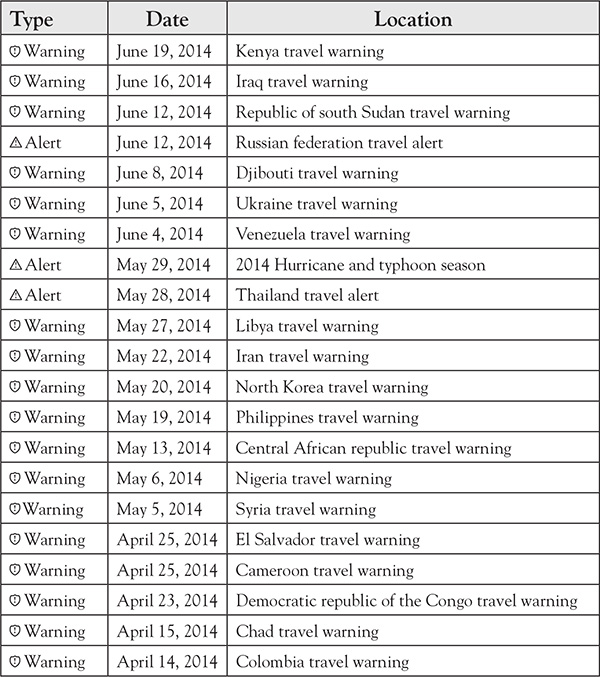

Travel warnings are very important to follow, as the DOS issues them when it wants travelers to consider carefully whether to enter into the country at all. Reasons for issuing a travel warning might include an unstable government, civil war, ongoing intense crime or violence, or frequent terrorist attacks. The U.S. government wants international travelers to know the risks of traveling to these places and to strongly consider not going at all. These travel warnings remain in place until the situation changes. Some have been in effect for years. They are often issued when long-term, protracted conditions lead the State Department to recommend Americans avoid or consider the risk of travel to that country. A travel warning¶¶ also is issued when the U.S. Government’s ability to assist American citizens is constrained due to the closure of an embassy or consulate or because of a drawdown of its staff. As of June 2014, the countries listed in Figure 3.6 meet those criteria.

Figure 3.6 List of countries in the U.S. Department of State travel-warning list as of June 2014

Source: U.S. Department of State

Managing Political Risk

Elisabeth Boone, chartered property casualty underwriter (CPCU) and manager of political risk and credit at ACE Global Markets,26 argues that very few companies actually have a formal approach to risk management when it comes to emerging markets. She indicates that although the great majority of companies she surveys and advise are aware that political risk management is important to their operations, just 49 percent of them integrate it formally into their investment process, while 41 percent take an informal approach to considering political risk as part of their investment process. This gap between awareness of political risk and formal action to manage it, Boone argues, is serious cause for concern given the fact that 79 percent of her survey respondents reported that their investments in emerging markets had increased over the past three years.

Not surprising, in the post-9/11 era is another survey finding that Boone deems noteworthy. She argues that there is “a perception that terrorism is a greater or at least an equal risk to U.S. assets as political risk, but if you look at the severity of what a confiscation would do to your balance sheet, I believe you’d want to consider political risk as an equal or greater threat in terms of lost investments.”***

Indeed, as discussed earlier, in some emerging markets governments seize foreign assets wholesale. In other areas they go after entire sectors. According to Boone, “We’re seeing that in mining, oil and gas, and telecommunications. So it’s not that they get one of your facilities; they take the whole thing. If you couple that risk with the fact that you don’t have an actual risk management process in place, the question becomes: What do you do if you’re hit?”†††

With emerging markets in every corner of the globe, some challenges for international business professionals and investors are bound to be specific to a particular country or political system. To answer the question of how to manage emerging market risk, you first have to define what is emerging market risk. Essentially, it’s volatility and uncertainty. Again, according to Boone, if “you’re in a place where there are unstable political, social, and economic conditions, are you able to clearly identify the risks? And if you have identified them, do you have a backup plan for how to respond to a crisis when it happens?”‡‡‡ Once you’ve made that investment you have to continue to monitor and manage the risk.

When considering emerging markets you must find ways to manage risks introduced by unstable and less predictable governments. International business professionals and investors may be faced with an uncertain legal environment, environmental and healthcare issues, volatile employment and labor relations, and the involvement of NGOs (non governmental organizations). It is important to consider reputational risk as well; being targeted by companies or countries that go after you for any reason.

For example, hedging corporate assets, insuring its resources (including personnel, equipment, properties, etc.) during the course of a project abroad is very important. Before an event or trip, organizations should develop claim management plans that establish clear roles and responsibilities for personnel inside and outside of the organization. As discussed in this chapter, instability can develop quickly. Hence, it is strongly advisable that key records, including insurance policies, contact lists, and financial and property records, should be accessible in hard copy and electronic formats via local and alternative location sources.

In the event of a loss, organizations should begin to gather data for a claim filing. This includes capturing potential loss information and additional costs associated with the claim, including temporary repairs, extra expenses, and business interruption loss of income costs. Businesses should record photographic and/or video evidence of damage and maintain open lines of communication between employees, insurers, and claims advisors to support policy loss mitigation and notification terms.

There are a few great companies, such as ACE Global Markets,§§§ that cover emerging market risks and focus on three areas: political insurance, trade credit, and trade credit insurance. Political risk insurance covers investments and trade by addressing confiscation of assets as well as interruption of trade in emerging markets due to political events. They also manage structured trade credit, short and medium term, and offer trade credit insurance.

* The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are eight international development goals that were established following the Millennium Summit of the United Nations in 2000, following the adoption of the United Nations Millennium Declaration.

† North Atlantic Treaty Organization, an international organization composed of the U.S., Canada, UK, and a number of European countries for purposes of collective security.

‡ The Muslim Brotherhood is a multi-national Islamic revivalist organization based in Egypt and founded by a primary school teacher, Hassan al-Banna. Originally established in 1928 as a social youth club stressing moral and social reform rooted in Islam, by 1939 it had turned into a political organization.

§ Member of a Shiite Muslim group living mainly in Syria.

** A type of rifle or submachine gun made in Russia, especially the AK-47 assault rifle.

†† International SOS is the world’s leading medical and travel security services company. They provide assistance to organizations in protecting their people across the globe. Their services are spread across more than 700 locations in 76 countries. For more information check http://www.internationalsos.com/en/

‡‡ Logit analysis is a statistical technique used by marketers to assess the scope of customer acceptance of a product, particularly a new product. It attempts to determine the intensity or magnitude of customers’ purchase intentions and translates that into a measure of actual buying behavior.

¶¶ Such information changes often, so we advise you to check the website for up-to-date information at http://travel.state.gov/travel/travel_1744.html, last accessed on 10/10/2013.

*** Ibidem.

††† Ididem.

‡‡‡ Ididem.