Coping With the Global and Emerging Market Crisis

Overview

After years of robust global economic growth, the implosion in advanced economy financial centers quickly began to negatively affect emerging market economies. Financial markets froze in the aftermath of the Lehman bankruptcy in September 2008 and the emerging markets faced an externally driven collapse in trade and pronounced financial volatility, magnified by deleveraging by banks worldwide further aggravated the situation. As a result, growth of the global economy fell six percent from its precrisis peak to its trough in 2009, the largest straight fall in global growth in the post-war era.

The global crisis had a pronounced but diverse impact on emerging markets. Overall, real output in these countries fell almost four percent between the third quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009, which was the most intense period of the crisis. This average performance, however, masked considerable variation across emerging economies. While real output contracted 11 percent during that period, the worst affected quarter for emerging markets, this was true mostly in emerging Europe only, as output rose one percent during the same period in other less affected emerging market regions, such as with the BRICS.

Emerging markets are still being confronted with two major factors as a result of the global financial crisis, as depicted in Figure 5.1, which include a sudden halt of capital inflows (FDI) driven by a massive global deleveraging, mostly from advanced economies, and a huge collapse in export demand associated with the global slump. Although some emerging markets were already predisposed for a homegrown crisis following unsustainable credit booms or fiscal policies, and faced large debt overhangs, the majority were not expecting the downturn and have been absorbing the hit from the unwelcome vantage point of surprise.

Earlier this year, in January 2014, emerging markets experienced the worst selloff in currencies in the past five years due to the Federal Reserve’s tapering of monetary stimulus, compounded by political and financial instability. The Turkish lira plunged to a record low and South Africa’s rand also fell to a level weaker than 11 per dollar for the first time since 2008. Argentine policy makers had to devalue the peso by reducing support in the foreign-exchange market, allowing the currency to drop the most in 12 years to an unprecedented low.

International business professionals and multinationals, as well as investors (in particular) are losing confidence in some of the biggest emerging nations, extending the currency-market rout triggered last year when the U.S. Federal Reserve first indicated it would scale back stimulus. Most financial analysts believe that while Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa were the engines of global growth following the financial crisis in 2008, emerging markets now pose a threat to world financial stability.

We believe, however, emerging markets will continue to grow at much higher rates than advanced economies, but not without pain and financial crises. The current emerging markets exodus isn’t like the last crisis in 1997–1998. Back then, emerging market governments borrowed heavily in dollars. When their currencies plunged, they had trouble paying their creditors. And while that scenario is still a concern for some countries, the majority of emerging market debt today is issued in local currency, and many do not owe as much as they did. In our view, analysts and commentators are still suffering from post-2008 financial shock. Despite the facile comparisons, emerging markets are not in as bad a shape as they were in 1997. According to The Economist,* only two emerging markets out of the 25 the magazine tracks have current account deficits of 5 percent GDP or more. Collectively, emerging markets boast foreign reserves of $7.7 trillion. China alone has, $3.7 trillion.

We also believe the vast majority of analyst commentary, especially those coming out of advanced economies, in particularly the United States, EU, and UK, miss the underlying reasons for emerging market currency volatility, with the yuan being the latest example. In our views, what we’re really witnessing is a major rebalancing of global economic trade. Prior to 2008, the United States had a massive consumption bubble, financed by its current account deficit which exported U.S. dollars and fueled global trade. Since the crisis, U.S. consumption has slowed but QE has stepped in to provide the U.S. dollar liquidity needed for world trade. With the tapering of QE, that dollar liquidity is diminishing, and emerging market currencies such as the yuan need to adjust to reflect real U.S. demand. Regardless of what the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the central bank of China, does, whether it intervenes or not, this situation was bound to happen. But even if emerging markets were to get hit, they will not necessarily take the rest of the world down with them.

The concern for emerging markets, however, is that this isn’t just a currency issue. The carry trades and subsequent inflows of capital have created substantial credit and real estate bubbles in many of these markets. The unwinding of these bubbles is likely to lead to banking crises in several countries, including China and China proxies such as Hong Kong, Australia, and perhaps even Singapore. We do not think this is likely to happen though. If it does, its impact on global economic activity will hurt inflated stock markets and commodity prices, particularly the likes of iron ore and copper which have been widely used as collateral to finance trades and purchases in China. In such case, the outcomes may be very favorable to the United States and the dollar, given less dollar liquidity means reduced supply vis-a-vis demand, as well as U.S. Treasuries, due to the deflationary consequences of the economic rebalancing.

As of 2014 emerging markets account for more than 50 percent of global GDP. Moreover, emerging markets, except for China, represent a third of global imports. If China is included, these markets account for 43 percent of imports. Hence, any slowdown in emerging markets will hurt their imports and therefore exporters in the developed world, including advanced economies. Furthermore, the profits of the United States and many European companies depend on overseas markets, particularly from emerging markets. According to Forbes, as of March 2014, more than 50 percent of U.S. Standards & Poor’s (S&P 500) profits are generated outside of the U.S.†

Advanced Economies Challenges

To make matters worse for emerging markets, advanced economies (G-7) are in a much worse economic situation. The G-7 economies and industrialized economies are struggling with debt and slow growth, which continue to impair its ability to trade and invest with emerging markets. Although these countries represent about 50 percent of world GDP, which totals around $30 trillion dollars, these countries also have a total debt of $140 trillion dollars, a remarkable 440 percent of their GDP. In 1998, total debt of the G-7 was $70 trillion dollars, and their GDP was $30 trillion dollars. Since then, total debt in these advanced economies has doubled between 1998 and 2012, from $70 trillion to $140 trillion, and GDP has risen only by $10 trillion.

In the eurozone, recent economic indicators support the idea that the common-currency area will return to moderate growth by 2014. The road to recovery, however, remains fraught with uncertainties, as the strictly economic issues are far more severe. It has been impossible to summon the necessary political will to take the needed steps until and only when the euro economy teeters on the brink of collapse. At each stage, when the markets crack the whip loudly enough, governments respond. But at each stage, the price of the necessary fix rises. Steps that could have resolved the crisis at one point are inadequate months later. At the time of these writings, the euro crisis continues to drag on without any concrete exit strategy. Greece is still a member of EU, along with Spain, Portugal, Italy, and France with varying degrees of threat. Germany continues to insist that the euro will survive while resisting bold steps to make it so.

Meanwhile, the relative international inactivity, especially during 2012, was partly due to an unusually large number of leadership changes, especially in East Asia. Most major countries, such as Russia, China, North Korea, South Korea, and Japan have witnessed changes of governments and heads of state. While political changes can be breathtakingly swift in the current global landscape, resolving or finding answers to complex economic challenges take time. During this slow economic recovery process, advanced economies have incurred $70 trillion additional debt to produce $10 trillion of additional GDP.

In other words, the world’s richest economies are coping with a market crisis where it needs $7 of debt to produce $1 of GDP. Furthermore, for every one percent increase in the borrowing interest rate in its debt, the G-7 adds a staggering $1.4 trillion dollars in debt, undeniably a massive amount of debt. Consider the fact that $1.4 trillion is only slightly less than the entire GDP of Canada. Should interest rates increase by 10 percent, these countries will be looking at an increase in interest expense that equals the entire GDP of the United States.

Some economic sources, policymakers and particularly the media have been suggesting that the G-7 economies, predominantly the eurozone, are slowly recovering, mainly in the UK. What that country is experiencing, however, in our view, is an expansion of nominal GDP. This is not equivalent to real economic growth, as GDP reflects money and credit being injected into the economy. People incorrectly assume this to be the same. Instead of economic recovery, GDP is reflecting money leaving financial markets, particularly bonds, for less interest-rate sensitive havens, which may benefit emerging markets, but has the effect of a double-edge sword. Globally, bonds represent invested capital of over $150 trillion, or more than twice the global GDP. Therefore, even marginal amounts released by rising bond yields can be financially destabilizing, and the effect on GDP growth could be significant.

It is our belief that the mistake of confusing economic progress, a better description of what global markets desire, with GDP is about to show its ugly side, pressuring interest rates to rise early and dragged up by rising bond yields. Take the United States for example, where personal credit in the form of car and student loans has been growing exponentially. The U.S. debt crisis is going up by at least $1 trillion every year. In addition, the U.S. Federal Reserve continues to expand its balance sheet by another $1 trillion each year, which means the U.S. government is currently printing $2 trillion dollars per year. At this pace, unless policymakers change course, we believe the country, and the world economy, will enter a more significant deterioration beginning in 2014. Under such scenario, which we hope won’t happen, the United States could be forced to borrow even more, and the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet would need to expand by several trillions of dollars.

Eventually it might be much more impactful than that, as in addition to the trillions of dollars of debt, the dollar likely will continue to fall, interest rates will rise, and a hyperinflationary economy starts. Meanwhile, prolonged negotiations in the United States, the largest economy and buyer in the world, regarding the country’s debt ceiling have increased uncertainty over its economic growth and that in turn is contributing further to dampening of the global economic growth.

The implosion of the U.S. debt will be extremely unpleasant for the world, particularly for those emerging markets that still rely on the U.S. imports, as well as those trading with other advanced economies invested in the United States. The authors, with sober judgment and concern, anticipate a very difficult time for advanced economies and emerging markets that may extend from 2014 through 2018 and beyond. They believe it will take a very long time for this debt accumulated by the G-7 countries to unwind and for the growth to recover.

It is critical, therefore, that emerging economies develop a credible exit strategy. IMF-like fund may be a good start for BRICS and other similar blocks such as ASEAN, MENA, and CIVETS trading with it, but monetary policy in these emerging countries should not be loosened too quickly, as a rapid reversal would just exacerbate the global currency wars‡ already at play and damage credibility for these countries.

The same holds true for fiscal policy interventions, where the stimulus should not be withdrawn too soon and not without a credible exit strategy that places government finances on long-term sustainable footing and helps contain the costs of financing the short-term stimulus. Such an exit strategy would bestow the benefit of strengthening investor confidence and facilitating the resumption of FDI inflows during the recovery phase.

The problem facing G-7 central planners is that a predominantly financial community that has the money to invest in capital assets, such as housing, automobiles, and other luxury items, drives the GDP whimsy. The vast majority of economic stakeholders comprising of pensioners, low-wage workers living from payday to payday, and the unemployed are simply disadvantaged as prices, already often beyond their reach, become even more unaffordable. It is a misfortune encapsulated in the concept of the Pareto Principal, otherwise known as the 80/20 rule. The substantial majority will be badly squeezed by rising prices generated by the spending of the few. Global markets are blithely assuming that advanced economies’ central banks are in control of events!

Unfortunately, the authors believe central banks are not even in control of their own governments’ profligacy, and they are losing their control over markets as well, as the tapering episode shows. In the authors’ view, the destructive error of rescuing both the banking system and government finances by heedless currency inflation is in the process of becoming more apparent. Unless this policy is reversed, the world risks a rerun of the collapse of the German mark witnessed in 1923. The printing of money will not positively contribute to long-term economic revival.

The central banks’ policies have caused debt to expand exponentially. This has greatly enhanced the economic power of the wealthy, and given the masses the illusion that they are better off, when all they have is a massive debt that can never be repaid. If we just look at the richest one percent in the United States, they have an average of 20 percent debt compared to 80 percent assets. But the masses, 80 percent of the people, have in comparison 90 percent vis-à-vis assets. This, of course, does not include government debt, which is also the people’s debt.

For decades, the United States and Europe have been the two centers of global governance. They have, on one hand the ability and experience in international problem solving and, on the other, both the energy and the will to act. All these are assets only when centers of global governance deploy them successfully. Once their model fails, the world will look elsewhere for leadership. At least in the foreseeable future, it will not find any substitutes. Hence, we argue that in the coming years, the United States and China will have to separate rhetoric and fear of the other from actual changes in global policy.

For instance, Stephen Ambrose2 already pointed out such foreign policy issues in his book Rise to Globalism. The author, while seeming to have a serious distaste for the U.S. Presidents Reagan and Johnson, believes Carter was an ideological senseless President that ended up doing the exact opposite of everything he stood for. While holding President Kennedy as naive and being led/misled by the people around him, the author seems to have the most admiration for Nixon, not as a person, but as a president. He felt Nixon’s administration was probably most up to the task of running a super-power.

For instance, a simmering conflict in the East China Sea will have to be managed through and beyond Japan’s elections. The United States will have to undo the damage wrought by its announced “Pivot to Asia.” The underlying message is that the U.S. is planning to increase its military presence in the region for the purpose of containing China and forcing Asian countries to choose between allying themselves with one or the other great power. It will take much time to convince China that the U.S.’ actual intent was, and is, to rebalance its attention from the Middle East toward East Asia, given that the United States has always attempted to exercise its power in Asian with diverse economic, political, and security interests there.

Emerging and Frontier Market Challenges and Opportunities

As discussed throughout this book, emerging markets have been on an inexorable rise over the past decade. During that period, the BRICS powered the high growth rate in emerging market economies, volatility notwithstanding. The rally, however, has started to trickle down in recent years, and came to a screeching halt in 2013, mainly due to fears of U.S. Federal Reserve tapering the stimulus and the slowdown of the Chinese economy.

It is important to note, however, that emerging markets entered the global crisis with varying economic maturity levels and conditions, and thus they are being impacted by the global financial crisis in diverse degrees. Some were already dealing with the beginnings of their own internal economic crisis associated with the end of unsustainable credit booms or fiscal policies, which left in their wake high levels of debt caused mainly by unhedged foreign currency exchange, which will probably require restructuring and perhaps write-offs. Other emerging countries were just caught up in the crash.

A number of emerging economies had to turn to the IMF for financial support. Increases in lending resources, as well as reforms to the lending framework enabled the IMF to quickly react to global developments and put in place 24 arrangements, many with exceptional access, including the recently introduced Flexible Credit Line.§ Other countries, many of them highlighted by Jim O’Neil in 2005, dubbed the Next 11, are poised to embark on rapid growth. Many of these countries have matured, improved their economic and trading policies, strengthened their institutions, achieved greater global credibility, and, in many cases, hoarded substantial war chests of foreign exchange reserves.

Progress, however, has not been across the board, with monetary and fiscal policies, FDI flow imbalances, and stock vulnerabilities, varying widely across these emerging economies. Emerging markets are not in “crisis,”; in fact, their growth outpaces that of the United States, Europe, and Japan. But there are many other emerging markets–such as the “frontier” states–that are performing very well economically and deserve attention.

Despite the slowdown of leading emerging markets, these breed of countries, often referred to, as “frontier” markets due to their small, unpopular, and illiquid economies, are prone for fast growth as well. Although these countries have not yet joined the global investment community, they have already joined the global economic community.

Lawrence Speidell¶ argued that the United States as the leading economy in the world as measured by both capitalization and trading volume, was a frontier market in 1792. At the time, the Buttonwood Agreement was executed at an outdoor location, under a buttonwood tree in New York City. It required brokers to trade only with each other and to fix commission rates. China was a frontier market by the late 70’s and early 80’s, and today, it is the second largest economy in the world, although it is classified as an emerging market.

The same was true for Argentina, once a frontier market, but by 1896, it was about three-quarters as prosperous as the United States and had one of the world’s leading stock markets. The country’s long decline, at least in relative standing, resulted in purchasing power parity GDP per capita in 2002 that was only double the 1896 level, whereas the United States grew sevenfold over the same period. Even though Argentina has enjoyed a strong recovery and is a solidly middle-income economy, as of this writing, its equity market is still classified as a frontier market because of capital controls that were imposed in 2005. In 2011, the country was in the process of removing these controls, but in 2013 and 2014 much of its progress was derailed, and inflation is accelerating and projected to hit 40 percent in 2014. Nonetheless, most frontier markets are more developed than we think, and set for fast economic growth.

Frontier markets are sometimes referred to as “pre-emerging markets.” These are countries with equity markets that are less established, such as Argentina, Kuwait, and Bangladesh. They tend to be characterized by lower market capitalization, less liquidity and, in some cases, earlier stages of economic development. But such markets are not just growth markets in distant places they represent more than 1.2 billion people. These emerging and frontier countries are also placing increasing demands on the world’s resources, as they become intensive consumers of basic commodities to support their infrastructure development and manufacturing. In the 1950s, the U.S. Interstate Highway System was built, and China is building its equivalent now. This trend is echoed in railway construction, power plant construction, and new building and bridge construction. It is not just China either. Developing countries around the world are undertaking such projects.

For several decades, frontier markets have been caught in a vicious circle of poverty, with little ability to develop savings for investment in future growth. What investment occurred in frontier countries was done by colonial powers that took out more than they put in. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is highly correlated with GDP growth and can be used as a measure of how the developing economies are faring in globalization. As FDI inflows increase in these markets, we believe that the frontier market growth opportunity is similar in many ways to the opportunity that existed 20 years ago for emerging markets, especially taking into consideration many of the mineral resources these countries have, as depicted in Figure 5.2.

|

Country |

Rank |

Resource |

|

Algeria |

6 |

Barite |

|

Algeria |

1 |

Lead |

|

Algeria |

1 |

Zinc |

|

Armenia |

6 |

Molybdenum |

|

Armenia |

2 |

Rhenium |

|

Botswana |

8 |

Copper |

|

Botswana |

2 |

Diamonds |

|

Botswana |

15 |

Nickel |

|

Botswana |

2 |

Soda |

|

Bulgaria |

14 |

Barite |

|

Guinea |

1 |

Bauxite |

|

Guyana |

8 |

Bauxite |

|

Kazakhstan |

11 |

Bauxite |

|

Kazakhstan |

8 |

Bismuth |

|

Kazakhstan |

9 |

Boron |

Figure 5.2 Mineral resource ranks for some of the frontier countries

Source: Speidell, Lawrence*

Following is a list of the main frontier and emerging market countries, sorted alphabetically and by GDP growth forecasts over the next five years, based on our own research and careful observations of economic data, political stability, and infrastructure challenges. Keep in mind that some measures in certain countries are mere estimates as real data may be lacking, and these estimates may vary considerably depending on our sources and timing. Progress has not been across the board though, as monetary and fiscal policies, imbalances in foreign direct investment, and stock vulnerabilities vary widely. This situation is aggravated by the fact that the media tend to emphasize news of conflicts, violence, drought, flood, and human suffering in frontier markets, shifting public opinion against them. Behaviors such as that of Robert Mugabe, president of Zimbabwe, who allowed inflation to reach an absurd 231,000,000 percent in 2008 is an example of news that fosters a general prejudice. But each country should be judged on its own merits.

Highlights of Some Frontier Markets

There are significant opportunities in frontier markets, especially considering their solid capital bases, young labor pool, and improving productivity, particularly in Africa, where the sub-Saharan region will, eventually, overtake China and India. It’s plausible to assume that Africa’s economy will grow from $2 trillion to $29 trillion by 2050, greater than the current economic output of both the United States and the Eurozone. But we must consider the frontier market’s deepening economic ties to China, which makes it vulnerable to a slowing Chinese economy. Also, frontier markets are not without risks, as local politics are complex, and there are still several pockets of corruption and instability. Further, liquidity is scarce, transaction costs can be steep, and currency risk is real. There’s also the risk of nationalization of industries.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh is a country the size of the state of Iowa in the United States. It is situated in the northeastern corner of the Indian subcontinent, and bordered by India and Burma. Although geographically small, in reality Bangladesh is a moderate, secular, and democratic country with a population of 160 million, making it the seventh most populous country in the world; notably more populous than Russia. Bangladesh is a big potential market for foreign investors, with a growing garment industry that supports steady export-led economic growth. The country is densely populated, with a rapidly developing market-based economy. Bangladesh is a major exporter of textiles and seafood, with the United States as its largest trading partner. Financial markets are still in their infancy, and thus present a major challenge for growth.

Bangladesh will soon attain lower-middle income status of over $1,036 GDP per capita, thanks to consistent annual GDP average growth of six percent since the 1990s. Much of this growth continues to be driven by the $20 billion garment industry, second only to China, and continued remittance inflows, topping $16 billion in 2013. In 2012, Bangladesh’s GDP reached $123 billion, complemented by sound fiscal policy and low inflation, which measured less than 10 percent in 2012.

Bangladesh offers promising opportunities for investment, especially in the energy, pharmaceutical, and information technology sectors as well as in labor-intensive industries. The government of Bangladesh actively seeks foreign investment, particularly in energy and infrastructure projects, and offers a range of investment incentives under its industrial policy and export-oriented growth strategy, with few formal distinctions between foreign and domestic private investors. Bangladesh has among the lowest wage rates in the world, which has fueled an expanding industrial base led by its ready-made garment industry. The country is well-positioned to expand on its success in ready-made garments, diversify its exports, and move up the value chain.

Egypt

As discussed in earlier chapters, Egypt has being politically unstable as a result of the Arab Spring that spread through the Middle East. This political uncertainty has caused massive damage to the economy. Egypt, the third largest economy in Africa, however remains an important emerging market in the region, and the substantial revenues from the Suez Canal, which it controls, makes it even more significant.

Furthermore, Egypt’s ability to withstand the financial burden of the revolution, for now at least, was helped by the remarkable growth it posted until December 2011. A financial reform program that began in 2003 had also helped create a well-capitalized and well-managed banking system. For Egypt’s economy to revitalize, however, much will depend on how the political process evolves over the coming months. Private-sector investment, which is important for meeting the job creation needs of the country, is currently on hold.

Indonesia

Indonesia is the fourth-largest country in the world by population. Not only it is a G-20 economy, but also the country has a significant and growing middle class with a society that is transitioning to a democracy. The country has relatively low inflation and government debt, and is rich in natural resources including oil, gas, metals, and minerals. Recently, with the fall of its currency, the rupiah, exports received a boost.

While advanced economies were slowing down and many emerging countries were experiencing slowdowns and exported ** financial crisis, Indonesia with a large domestic market and less reliance on international trade, grew through the global financial crisis. Domestic demand constituted the bulk of output in Indonesia, about 90 percent of real GDP in 2007.

Many other emerging markets that also either grew through the crisis or experienced relatively small adverse impact had large domestic markets, such as in China, Egypt, and India. Indonesia also benefited from increased spending associated with national elections in 2009. Hence, Indonesia is recovering faster than many other emerging countries, in part due to a well-timed stimulus. From the first through the last quarters of 2009, output grew 4.5 percent, well above the emerging market’s average of 3 percent for the same period. Fiscal stimulus was a step ahead of the curve. As the global economic crisis struck, the government topped up the existing fiscal loosening with cash transfers and other social spending to protect the poor and support domestic demand. The monetary policy response and liquidity management by Bank Indonesia also supported the recovery.

Iran

Although one of the largest oil exporters in the world, Iran’s economy is unique as 30 percent of the government, spending goes to religious organizations, which is a major challenge for achieving sustainable growth. The other challenges include administrative controls and widespread corruption and these outweigh positive factors such as a younger, better-educated population, and rapid industrialization. Yet another challenge is the constant risk of economic sanctions and military conflicts. As long as Iran remains committed to supporting terrorism and its nuclear weapons program, any foreign direct investment opportunity will continue to remain unrealistic.

The United States and EU sanctions targeting Iran’s oil exports have hit the country harder than earlier measures, as these financial sanctions have seriously disrupted Iran’s trade, for which government authorities were ill prepared. As of fall 2013, Iran was still trying to figure out how to cope with a currency crisis and higher inflation.

Since sanctions were imposed, the rial has fallen to record lows against the U.S. dollar with some reports suggesting it had lost more than 80 percent of its value. The sanctions have slashed Iran’s oil exports to around one million barrels a day (b/d). As tensions have increased over Iran’s controversial nuclear program, with the United States leading a campaign to undermine the country’s economy for coercing the leadership to rescind its policies, the authorities in Tehran have become more secretive over economic data.

Nigeria

As the largest African nation by population, Nigeria is projected to experience high GDP growth rate in the next few years and perhaps for the next several decades. Oil and agriculture account for more than 50 percent of the country’s GDP, while petroleum products account for 95 percent of exports. The industrial and the service sectors also are growing. This economic growth potential spurs significant FDI initiatives, mostly from China, the United States, and India. The challenge, however, is with its legal framework and financial markets regulations, which leave much to be desired.

Pakistan

As another frontier market, we believe Pakistan has potential for growth based on its growing population and middle class, rapid urbanization and industrialization, and ongoing, albeit slow, economic reforms. Pakistan has experienced significant growth for several decades. From 1952 until 2013, Pakistan’s GDP growth rate has averaged 4.9 percent, reaching an all-time high of 10.2 percent in June of 1954 and a record low of −1.8 percent in June of 1952. Since 2005 the GDP has been growing at an average of five percent a year, although such growth is not enough to keep up with its fast population growth. Its GDP expanded 3.59 percent from 2012 to 2013.†† According to the World Bank,3 the Pakistani government has made substantial economic reforms since 2000, and medium-term prospects for job creation and poverty reduction are at their best in nearly a decade.

Pakistan’s hard currency reserves have grown rapidly. Improved fiscal management, greater transparency and other governance reforms have led to upgrading of Pakistan’s credit rating. Together with the prevailing lower global interest rates, these factors have enabled Pakistan to prepay, refinance and reschedule its debts to its advantage. Despite the country’s current account surplus and increased exports in recent years, Pakistan still has a large merchandise-trade deficit. The budget deficit in fiscal year 1996–1997 was 6.4 percent of GDP. The budget deficit in fiscal year 2013–2014 is expected to be around four percent of GDP.

In the late 1990s Pakistan received roughly $2.5 billion dollars per year in loan/grant assistance from international financial institutions such as the IMF, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank (ADB).4 Increasingly, however, the composition of assistance to Pakistan shifted away from grants toward loans repayable in foreign exchange. All new U.S. economic assistance to Pakistan was suspended after October 1990, and additional sanctions were imposed after Pakistan’s May 1998 nuclear weapons tests. The sanctions were lifted by President George W. Bush after Pakistani President Musharraf allied Pakistan with the United States in its war on terror. Having improved its finances, the government refused further IMF assistance, and consequently ended the IMF program.5

Despite such positive GDP growth, Pakistan is still one of the poorest and least developed countries in Asia, with a growing semi-industrialized economy that relies on manufacturing, agriculture, and remittances. To make things worse, political instability, widespread corruption and lack of law enforcement hamper private investment and foreign aid.

Ahmed Rashid, an investigative journalist with the Daily Telegraph in Lahore,‡‡ exposes many facets of Pakistan’s political instability in his book titled Pakistan on the Brink,6 where he argues that the bets the U.S. administration has made on trusting Pakistan to support its war efforts in destroying Al Qaeda were not working. Pakistani Taliban, for instance, while pursuing terrorism within Pakistan, has killed more than 1,000 traditional tribal leaders friendly to the Pakistan State, and views the state as an enemy due to its tacit support to U.S. drone attacks. The Taliban’s aim, according to Rashid, was, and still is, to establish an Islamic caliphate§§ ignoring political borders.7

Pakistan’s political framework, Rashid contends, continues to be dominated by its army. Hence, civil government is weak, corrupt and powerless. Apart from the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party¶¶ (PPP) there is no other national party, as all other parties are either ethnic or regional, making democracy difficult in a society where the 60 percent Punjab population dominates civil service and the army; others feel underprivileged. Pakistan’s political elite has failed to create a national identity that unifies the country. The army’s anti-India security paradigm has filled the void to define national identity making the army the most important component of the country.

According to the Asian Development Bank8 (ADB), the new government that took office in June 2013, however, quickly signaled restoring economic sustainability and rapid growth as high priorities for its five-year term. It emphasized focus on the energy crisis, boosting investment and trade, upgrading infrastructure, and ceding most economic functions to the private sector. To address low foreign exchange reserves, fiscal and external imbalances, and low growth, the government agreed on a wide ranging economic reform program with the IMF, supported by a three-year loan worth $6.7 billion dollars.

The program aims to eliminate power subsidies in fiscal consolidation that include strengthening the country’s notorious weak revenue base and ending the drain from debt-producing public enterprises. Other structural reforms hope to strengthen the financial system and improve the business climate. ADB*** contends that fiscal consolidation would limit GDP growth in 2014 to 3 percent. The current account deficit forecast remains at 0.8 percent of GDP, as the foreign reserve position strengthens. The monetary program is likely to limit average inflation to 8 percent for 2014.

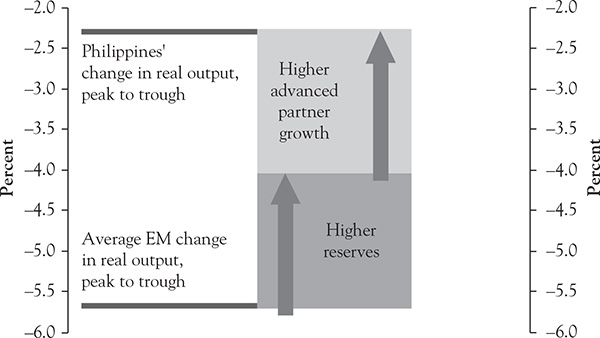

Philippines

The Philippines has shown strong economic progress in the past few years, as shown in Figure 5.3, posting the highest GDP growth rates in Asia during the first two consecutive quarters in 2013. The country weathered the global economic crises very well owed to significant progress made in recent years on fiscal consolidation and financial sector reforms, which contributed to a marked turnaround in investor sentiment, fostering significant FDI inflows.

Figure 5.3 Philippines’ contributions to growth performance relative to average emerging market growth

Source: Haver; Bloomberg; IMF9

The government used this opportunity of increased FDI inflows to build reserve buffers while keeping exchange rate flexible. Hence, the Philippines entered the global financial crisis on the back of significant improvements in external exposures, which afforded them a smaller output.

The challenges, as a newly industrialized country, are that the Philippines is still an economy with a large agricultural sector, although services are beginning to dominate the economy. Much of the industrial sector is based on processing and assembly operations in the manufacturing of electronics and other high-tech components, usually from foreign multinational corporations. As with many emerging markets, the United States remains Philippines largest trading partner.

Turkey

Turkey’s economy, much like the Philippines, has been growing at a fast pace, and for much of the same reasons. Rapid industrialization coupled with steady economic reforms has made Turkey an attractive emerging market. In 2013, however, Turkish economy suffered with civil unrest in the summer and the U.S. taper talk. Turkey’s economy remains prone for FDI inflows, but it draws its strength from the country’s political stability, unique geographical location on the border of Europe and Asia, market maturity, and economic growth potential.

Vietnam

While agriculture still accounts for 20 percent of Vietnam’s GDP (rice and coffee remain the most important crops), its industry and service sectors continue to grow. The major challenge is still its authoritarian regime, which causes its economy to be split between state planned and free market sections. In addition, its economy is still volatile, despite much progress, due to relatively high inflation, lack of transparency in government policy, and a dearth of large enterprises.

MENA Challenges

The Middle East continues to be consumed with the political upheavals of the Arab Awakening: Islamists moving from the familiar role of opposition to the far harder job of governing, religious movements being transformed into political parties, the struggle to organize secular parties, the writing of constitutions, and the holding of elections. In the coming years, it seems likely that sectarian strife will become the defining thread of events across the region.

Through decades of otherwise ineffective rule, the Middle East’s dictators did manage to keep divisions between Sunnis and Shia under control. The enforced peace first unraveled in Iraq, where the American invasion triggered a sectarian civil war. The political agreements imposed under the U.S. occupation began to unravel after the departure of American forces, and Iraq today looks like a country about to splinter into Kurdish pieces, late into separate Shia and Sunni pieces, in par, due to Iranian Shia influence.

Iran’s mullahs are also playing a major role in Syria, where minority Shia rulers are fighting for very existence in a largely Sunni country. Christians, Kurds, and others are also fighting together and extricating from their countrymen. Sunni and Shia governments across the region ship arms and money to like-minded groups, choosing sides in this second sectarian civil war. Only miles from Damascus, Lebanon—always a sectarian tinderbox—tries desperately to hold on to its fragile peace.

In Bahrain, uprisings, brutally repressed by a Sunni government in a Shia-majority country, are also along sectarian lines. When it comes to foreign affairs, poorly chosen words can do lasting damage. The “Pivot to Asia” was one such example; the other was the “Arab Spring,” which led many to expect that the upheavals in the Middle East would lead to swift change and resolution. Unlike the end of Soviet rule in Eastern Europe, these are genuine internal revolutions that will take decades to play out.

The challenge for advanced economies, especially the United States and EU, is to develop the necessary strategic tolerance to distinguish between inevitable ups and downs and long-term trends while helping new governments deliver the economic progress they will need for political survival. We believe Egypt’s extraordinarily complex political evolution will continue to play out for the next few years. Overall, events there have been encouraging—the discipline of governing has exerted a moderating influence on the Muslim Brotherhood, the military has relinquished a desire to rule, the country has stuck by its agreement with Israel, and political violence is the exception, not the rule.

In Libya, the government will continue to struggle to take back a government’s rightful monopoly on the use of force for internal security from well-armed militias, helped by its oil revenues but hampered terribly by the country’s complete lack of functional institutions after forty years of Qaddafi’s personal rule. Governments in countries where unrest is still below the surface—Jordan, Kuwait, the Gulf emirates, and Morocco—will continue to stall, hoping that the greater legitimacy they enjoy as monarchies will enable them to avoid major protests and, therefore, retain power. Syria, Iraq, and Iran are where fundamental change is most likely in the year ahead.

As of fall 2013, much is in flux in Israel. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu will have to reevaluate his options in light of the outcome of the U.S. election and public opposition to war. Though his political opposition is weak, elections scheduled for January could force adjustments in Israeli policy.

Other Emerging Market Challenges

The major challenges in the Latin American region are the deterioration of its global economic outlook. We expect regional GDP to expand 3 percent in 2014, as there has been a negative trend in growth prospects for Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Venezuela, although growth prospects for Bolivia and Ecuador are positive. Brazil and Mexico will likely grow at a 2.7 percent, which we believe to be a rebound trend from the nearly uninterrupted negative trend downward that began in June 2012.

The deterioration of some BRICS economies, particularly Russia and India also has contributed to the slowdown of global growth. Within Latin America, we believe Brazil and Mexico will experience growth starting in 2014. In the late summer of 2013 Brazil’s economy grew 0.1 percent over the previous month, from a decline of 0.3 percent in July.

Mexico is the second-largest economy in Latin America, following Brazil. The country, which has been on the U.S. FDI radar for some time, is a G-20 member and democracy. Its geographical location and the NAFTA agreement make the United States its largest trading partner. Mexico’s low inflation and unemployment add to the economy’s promise.

Mexico has been engendering much confidence with both policy reforms and the country’s inherent strategic advantages. It is easy to forget just how sizable the economy is. At 14th in the world, ahead of South Korea, Mexico enjoys a balanced government budget, a steadily growing population, a dramatically reduced deficit and relatively high interest rates. The country boasts many large multinational companies, as depicted in Figure 5.4,10 many of them are listed in the U.S. stock exchanges.

|

Rank |

Name |

Industry |

Foreign assets |

|

1 |

Cemex |

Non-metallic minerals |

40,334 |

|

2 |

America Movil |

Telecommunications |

23,610 |

|

3 |

Carso Global Telecom |

Telecommunications |

11,768 |

|

4 |

Grupo FEMSA |

Beverages |

3,508 |

|

5 |

Grupo ALFA |

Diversified |

3,439 |

|

6 |

Grupo México |

Mining |

2,850 |

|

7 |

PEMEX |

Oil & gas |

2,090 |

|

8 |

Gruma |

Food products |

1,986 |

|

9 |

Grupo BIMBO |

Food products |

1,850 |

|

10 |

Grupo Televisa |

Television, motion pictures, radio & telecommunications |

1,614 |

|

11 |

Cementos de Chihuahua |

Non-metallic minerals |

952 |

|

12 |

Industrias CH |

Steel & metal products |

790 |

|

13 |

Mexichem |

Chemicals & petrochemicals |

730 |

Figure 5.4 Ranking of Mexican multinational companies, as of 2008

Source: Columbia University

The Mexican economy also is expected to grow, although in this case it is providing mixed signals. The external sector continues to show healthy developments as Mexican exports grew solidly in early fall of 2013. Nonetheless, the manufacturing indicator fell in October 2013 after three consecutive months of improvement. The index is again below the 50-point threshold, which separates expansion from contraction in the manufacturing sector.

While the Mexican government’s push for economic reforms promises to boost economic growth in the medium- to long-term, short-term economic headwinds persist amid uncertainty in the U.S. economy, sluggish domestic demand, and a negative weather-related impact. We believe Mexico is prone to grow 3.5 percent in 2014. Against a backdrop of contained inflationary pressures and sluggish domestic demand, central banks across Latin America must decide whether to lower or maintain interest rates in order to support economic growth. We expect Mexico’s central bank to cut interest rates, but not so in Brazil, as the country’s central bank is still involved in a tightening cycle.

Led by a collapse in domestic demand, Russia experienced a sharper-than-expected contraction in output during the global economic crisis causing the output to fall sharply by about 11 percent of GDP from its peak. Compared to many other emerging economies, Russia had much lower external vulnerabilities when the crisis started, but the country suffered one of the largest output downfalls in the emerging markets. Oil prices were an important factor in the collapse of Russia’s outputs.

As oil prices collapsed in the midst of the global recession, trading partners revised their outlook for the economy and the ruble, causing the domestic demand to plunge due to the immediate change in policies by trading partners. At the same time, capital outflows, banks’ increased risk aversion, and an associated credit crunch exacerbated the collapse. High oil prices may have masked inefficiencies in un-restructured sectors.

In addition, a pre-crisis credit boom fueled in part by a rigid exchange rate regime helps explain the eventual impact of the crisis. Through 2007, Russia was growing at seven percent per year on average, driven by high oil prices, expanding domestic demand, and a credit boom. As a result, by the time of the crisis, some corporations and banks had become increasingly reliant on short-term capital flows.

As the crisis unfolded, Russia spent more than $200 billion of its reserves, the equivalent of about 13 percent of its 2008 GDP in an attempt to temper the pressure on the ruble, but eventually the government appeared to given up and allowed for a significant fall in the exchange rate. This was one of the largest declines amongst emerging markets.

Russia’s high reserves provided some space for corporates and banks to adjust to a revised global outlook with lower oil prices, and this helped Russia to avoid the crisis from spinning out of control completely. Nevertheless, this had its own costs. Some market participants were able to benefit from speculating on the eventual devaluation, and some of the problem banks will eventually need intermediation to support the recovery.

Conclusion

This chapter ends where it began. Even though the global crisis started in the financial markets of advanced economies, emerging markets suffered a heavy toll. The median emerging market economy suffered about as large a decline in output as the median advanced economy, but the impact was more varied in emerging markets, as depicted in Figure 5.5. Several emerging markets were impacted more than the worst hit advanced economies, while other emerging markets continued to grow throughout the crisis period. While on average emerging markets experienced significant decline in stock markets and as wide span as advanced economies, there was considerable cross-country variability.

|

Impact of the crisis |

||

|

|

Emerging markets |

Adduced economies |

|

Output collapsea |

||

|

Median |

−4.3 |

−4.5 |

|

25th percentile |

−8.4 |

−6.6 |

|

75th percentile |

−2.0 |

−2.9 |

|

Stock market collapsea |

||

|

Median |

−57.1 |

−55.4 |

|

25th percentile |

−72.0 |

−64.1 |

|

75th percentile |

−45.2 |

−49.0 |

|

Rise in sovereign spreadsb |

||

|

Median |

462 |

465 |

|

25th percentile |

287 |

. . . |

|

75th percentile |

772 |

. . . |

aMeasured as percent change from peak to trough.

bMeasured as increase in basis points Irom trough to peak. For A Es, table reports rise in spreads on US corporates rated BBS.

Figure 5.5 The impact of the global financial crisis on advanced economies and emerging markets

Source: Haver; Bloomberg; IMF

Countries with higher pre-crisis vulnerabilities and trade and financial linkages with the global economy, in particular the advanced economies, were more impacted by the crisis. Countries that experienced a decline in vulnerabilities before the crisis came out well ahead of others. One of the factors that lowered pre-crisis exposure was higher international reserve in relation to short-term external financing needs. Nevertheless, additional reserves were less useful at limiting output collapse at very high levels of reserves.

In our view, no foreign policy issue, in 2014 and beyond, will matter as much for the global economic, political, and ultimately security conditions as the ability or the willingness of the United States and EU to deal decisively with their economic crises. If the United States can find an exit strategy for its “fiscal cliff,” the resolution of the acute economic uncertainty would unleash private sector investment, spark an economic recovery, and enhance the country’s pivotal international role.

Advanced economies have responded to the crisis through unprecedented monetary and fiscal easing. As for the emerging markets, those in the midst of a homegrown capital account crisis may have to orient their policies toward restoring confidence in the currency, with little scope for easing in either dimension without exacerbating capital outflows. Emerging markets with credible inflation targeting frameworks should have considerable scope for monetary policy easing without compromising their inflation outlooks.

Likewise, the collapsing external demand and weakening domestic economic activity would, in general, call for fiscal easing to support demand, provided debt sustainability is not a concern and financing is available. Given a targeted level of aggregate demand/inflation, a more expansionary monetary policy can compensate for a less expansionary fiscal policy—though both may be relatively ineffective if domestic credit markets are frozen. Substituting for monetary easing by fiscal expansion can be constrained by debt sustainability concerns, because both relatively higher interest rates and fiscal spending will exacerbate debt dynamics.

There is no one-size-fits-all prescription, and the appropriate policy mix depends on the particular circumstances in each country, including a number of trade-offs. For Europe, the world’s largest economic entity and a critical leader of a liberal and peaceful world order, the challenge continues to be to summon sustained economic discipline and political will.

Progress has been made. Governments have firmly convinced themselves, if not the markets, that they will do whatever it takes to save the euro. Thanks largely to the efforts of two Italians—Mario Monti, the economist appointed interim prime minister to put Italy’s house in order, and Mario Draghi, the new head of the European Central Bank—concrete steps have been taken that show a rescue is possible. But painful structural reforms will have to be endured for many years—a tall order for any one democracy, let alone for many sharing each other’s pain. In effect, the euro crisis morphed in 2012 from a life-threatening emergency to a chronic disease that will be with us for years to come. The challenge for 2014–15 is to maintain the harsh treatment, avoid setbacks (in France, especially), and continue to inch toward restored growth.

For emerging markets, recovery was underway in most of the nations by late 2009, with considerable variation across countries. On average, real GDP expanded three percent in emerging markets during the last three quarters of 2009, but as in the impact of the crisis, this masks considerable cross-country variation. For instance, countries not pegging to the dollar, or other advanced economy currency, recovered much faster than those that were pegged. Across emerging market regions, as depicted in Figure 5.6, the recovery was most pronounced in Asia, particularly in the ASEAN bloc, and least in emerging Europe.

|

Recovery from the Crisis (averages, percent) |

||

|

|

GDP growth, 2009Q4/2009Q1 |

Industrial production growtha |

|

(1) |

(2) |

|

|

All EMs |

3.1 |

10.8 |

|

By exchange rate regime |

||

|

Fixed exchange rate regimes |

0.2 |

−1.6 |

|

Flexible exchange rate regimes |

3.9 |

14.0 |

|

By region |

||

|

Asia |

6.4 |

26.7 |

|

Europe |

1.2 |

4.3 |

|

MCD |

4.8 |

10.9 |

|

Western hemisphere |

3.1 |

9.7 |

aFrom each country's trough to Dec. 2009.

Figure 5.6 Emerging markets recovery from the global financial crisis

Source: Haver; IMF AREAR; IMF

* http://www.nasdaq.com/article/the-global-guru-heres-why-the-emerging-markets-crisis-of-2014-is-a-red-herring-cm323946#ixzz358xbDGgR

‡ Paraphrasing James Richards in his book Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis, Portfolio Trade, 2012.

§ The Flexible Credit Line (FCL) was designed to meet the increased demand for crisis-prevention and crisis-mitigation lending for countries with very strong policy frameworks and track records in economic performance. To date, three countries, Poland, Mexico and Colombia, have accessed the FCL: due in part to the favorable market reaction, none of the three countries have so far drawn on FCL resources. http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/fcl.htm.

¶ Speidell, Lawrence (2011-05-13). Frontier Market Equity Investing: Finding the Winners of the Future (Kindle Locations 67-68). CFA Institute. Kindle Edition.

* Speidell, Lawrence (2011-05-13). Frontier Market Equity Investing: Finding the Winners of the Future (Kindle Locations 612-615). CFA Institute. Kindle Edition.

** Exported financial crisis from advanced economies, and devaluation of those currencies caused inflation in these countries due to hot money inflows.

†† http://www.tradingeconomics.com/pakistan/gdp-growth (last accessed on 03/23/2012).

‡‡ Lahore is the capital of the Pakistani province of Punjab and the second largest and metropolitan city in Pakistan.

§§ A caliphate is an Islamic state led by a supreme religious as well as political leader known as a caliph (meaning literally a successor, i.e., a successor to Islamic prophet Muhammad) and all the Prophets of Islam.

¶¶ Pakistan People’s Party is a center-left, progressive, and social democratic political party in Pakistan.

*** Ibidem.