CHAPTER 7

Producing Powerful Products

People don’t pay for technology. They pay for a solution

to their problem or for something they enjoy.

Dean Kamen, Founder, DEKA Research

and Development Corporation

Last year, consumer-products makers churned out more than 31,000 new products, including multiple varieties of everything from tomato sauce to garbage bags to iPod cases.

Few of these products will survive. And fewer yet will become breakthroughs. The most optimistic estimate is that only one in five launches will succeed; the most pessimistic, one out of 671. Many failures result from basic miscalculations about what customers need. The product is developed for all the wrong reasons. It was the CEO’s pet project. The engineers fell in love with the “really neat” technology and assumed buyers would too.

Among the more egregious examples:

- Nestea’s Tea Whiz, a yellowish carbonated beverage. Hmmm, maybe a poor choice of product name?

- 138Ben-Gay Aspirin. Lesson: if you specialize in a product that’s hot to the touch, it’s probably not a good idea to attempt a line extension with a digestible version of that product.

- Premier, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco’s attempt at a “smokeless cigarette” that would satisfy smokers without the health hazards. One small oversight: smokers enjoy the smoke and the taste of burning tobacco but Premier had neither.

Driving Growth Via New Products

Consumer products makers aren’t alone in introducing such a high percentage of failures. Many firms today, both in the manufacturing and services arenas, struggle with developing new products that drive top- and bottom-line growth. The pressure to produce more new products with shorter time to market intervals and bigger payoffs is enormous. Attempts at product innovation by many companies bring to mind Samuel Johnson’s description of a dog walking on its hind legs. “It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.”

Most firms today focus on, and have become steadily better at, taking costs out of the manufacturing operations. They focus on incremental improvements to existing products and add endless line extensions to remain at parity with competitors.

Innovation Vanguard companies set different priorities. Instead of focusing on their competition, they focus on their customers, their needs today and the unarticulated needs, wants, and desires they can satisfy tomorrow. Instead of focusing on shareholder value, they focus on creating exciting, unique customer value, believing that if customers are served, shareholders will be ultimately rewarded.

How Innovation-Adept Firms Approach Product Innovation

Kuczmarski & Associates is a highly respected Chicago-based new product development consultancy firm. Not long ago Kuczmarski conducted a study of 209 companies’ practices in new product and service management, seeking to determine the characteristics of the most successful organizations. What they found was eye opening:

139- The best new product companies enjoy higher rates of growth and greater profits and stock valuations than the rest. More than three-quarters (77.8 percent) of the “best” companies believed that their new products and services processes contributed to their success. By contrast, less than a third (26.4 percent) of the rest said so.

- Less than half (48.8 percent) of all companies formally measure speed to market of new product/service introductions. Fewer than five percent of all companies (4.3 percent) measure return on innovation investment (ROII).

- A majority of companies do not formally measure new product/service success rates at all.

- The “best” new product/service firms (70.6 percent) provide more consistent and effective senior management support to new product/service development. Only 40.4 percent of the “rest” receive such support.

- The “best” are most often “market innovators” (70.6 percent) versus only 26 percent of the “rest.”

- A majority of the “best” new product/service companies (55.8 percent) are moderately or highly supportive of risk-takers during new product development. But less than one-third of the “rest” (28.1 percent) are. Forty-eight percent of the “rest” describe their new product strategy as “low risk imitation, not pioneering.”

- The “best” companies conduct customer-need identification research more consistently and effectively than the “rest”: 37.7 percent versus 5.0 percent.

- A slight majority (52.9 percent) of the “best” new product/service companies solicit customer input and feedback prior to idea generation. But only a third (32.6 percent) of the “rest” conduct customer needs research prior to idea generation.

Six Strategies for Producing Powerful Products

Kuczmarski’s study parallels the survey findings of consultancy Arthur D. Little, Inc. that we first reported in the Introduction. Recall that of 669

140Producing Powerful Products

- Study previous breakthrough products.

- Focus relentlessly on value creation throughout the development process.

- Design and implement a new product development process.

- Use a learning strategy for more radical ideas.

- Use cross-functional teams.

- Use rapid prototyping.

global executives surveyed, fewer than one in four believe their companies have “mastered the art of deriving business value from innovation.”

The good news is that no matter the state of a firm’s new product development processes at present, with effort that firm can revamp its approach and thereby use new products to drive growth. Here are six strategies for producing powerful, revenue-growing products:

Product Innovation 1: Study previous breakthrough products.

Throughout this book, we’ve looked at a number of breakthrough products. We’ve seen how some of them were the result of a happy accident. How NutraSweet, today a $2 billion a year product for G.D. Searle Company was discovered by a researcher attempting to find a drug to treat ulcers. Pfizer’s Viagra was “accidentally” discovered by scientists attempting to stimulate receptors in the human heart. Canon’s ink-jet printer was discovered when a technician left a soldering iron on near a bottle of ink.

We’ve also seen how some breakthrough ideas came about because they were first to exploit change, as Federal Express did with its Overnight Letter product and McDonald’s did in creating a whole new range of products when it first opened for breakfast. But what to do if you want to consciously go after breakthroughs? What would you do? One answer: study previous breakthrough products.

Below is a list of breakthrough ideas, some of which we’ve discussed in earlier chapters and some that we haven’t. What do these ideas have in common?

141What do these products have in common? Let’s take a look:

Breakthroughs provide a superior solution to problems the customer recognizes as problems. Gillette’s Sensor razor when launched globally in the early 1990s became an immediate best-seller. The market—men with whiskers—was familiar to Gillette, but Gillette’s new razor was so superior in producing a noticeably closer shave, that that was enough. Breakthroughs like Sensor push the envelope in terms of affordability, speed, mobility, portability, convenience, customization, choice or level of service.

Breakthroughs provide a solution to problems the customer didn’t recognize he or she had, until the product came along. In the 1970s and 1980s, American businesspeople began to travel more frequently as part of their jobs. In response, entrepreneurial firms invented organizer notebooks. On-the-go professionals adopted models with names like Day-Timer and Filofax as a solution to a new problem: staying organized while being mobile. These products contained an address book, pages to take notes, various references, and an appointment calendar. Companies that were first movers prospered in converting the professional classes to this new solution. Then, when Palm Computing’s Pilot Organizer provided these same features in a smaller, light-weight electronic device, it became a superior solution to millions of users.

142Breakthroughs often resolve a contradiction. Customers often have contradictory needs. They want to drink beer but they also want to reduce caloric intake. Products like Miller Lite, along with a plethora of “low-calorie” foods, purport to help them do both. Think of any two terms that describe inexpensive or low-end products or services with those usually associated with high-end or luxury ones and by offering both, you resolve the customer’s contradiction.

Kimberly-Clark listened to customers who purchased Huggies disposable diapers and stumbled upon an unresolved contradiction. Parents told researchers they didn’t want their toddlers to have to wear diapers any more, even though their kids were still not toilet-trained. At the same time, they didn’t want their children to have accidents or to wet the bed. Kimberly-Clark’s solution, Pull-Ups, mitigated this contradiction and became an immediate Breakthrough Product for the firm.

Breakthroughs provide customers with an enabling new benefit often beyond the product itself. If you visit the Henry Ford Museum in Detroit, you will see, among other objects on display, hundreds of early farm machines and devices, many of which never caught on. But one of them did: Cyrus McCormick’s harvesting machine, the reaper. Was the reaper so superior to other machines on the market at the same time? What innovation scholars believe put Cyrus McCormick’s invention out ahead of the pack was a novel enabling benefit. McCormick sold to farmers on credit—a strategy innovation—allowing thousands of farmers that could not otherwise afford the machine to pay him off over time.

Henry Ford’s enabling benefit was to continue to reduce the price of his Model T to make it affordable to the middle class. Callaway Golf’s Bertha enabled even average golfers to drive the ball farther and straighter, even if they didn’t hit it with perfect form. Medtronic’s Pacemaker allowed patients with heart conditions increased mobility and the opportunity to carry on with their lives, even though afflicted with a heart condition.

Breakthroughs go against conventional wisdom. Rather than succumbing to what seemed like the inevitable rise of Microsoft’s Windows and Intel chips in high-powered servers, Sun Microsystems went against conventional wisdom and developed its own system instead. Sun focused its research spending on its own brand of Unix, Solaris™ and its own in-house chip, 143the SPARC™. When Microsoft’s operating system didn’t evolve fast enough and robustly enough to handle the heavy lifting required of a web server, Sun’s Unix server became a breakthrough. As Unix servers became the backbone of the web, Sun sold more of them than Hewlett-Packard, IBM, and Compaq combined.

Well, that’s our list and it’s only partial. What observations might you add? Identifying the qualities and characteristics of breakthrough ideas could fill the pages of a book, but you can use this partial list to stimulate your thinking about the qualities and characteristics that will describe your next product. Start by listing the recognized breakthroughs in your industry. What ideas have enlarged the pie for everybody? And more importantly, what’s next?

Product Innovation 2: Focus relentlessly on value creation throughout the development process.

Companies often maintain they want to innovate but their customers are resistant to any changes. They are risk averse, don’t want new and improved, and don’t want to pay higher prices for premium, value-added products. There’s no question customers say this and that they believe it. What it really means is that they haven’t seen strong enough reasons to pay more to satisfy their needs and go to the trouble of switching to something new. Customers naturally want to think of your products as commodities so they can negotiate the lowest price, but don’t let your vision be limited by this tendency.

Instead, focus on creating a greater amount of value for the customer as you develop the new product or service. Ideas fail in the marketplace because firms lose sight of the value they deliver to customers. A relentless customer value focus needs to be at the heart and soul of every decision, every meeting, and every person on the team. It’s a time-honored path to success. If you analyzed a hundred breakthrough ideas, what you would find is that virtually every one created new value for the customers.

The genesis of most companies’ new offerings is just the opposite. Instead of “what will this do for the customer,” it’s “what will this do for us?” Meaning, what will this new product do for us to raise profits, grow the business, make us rich, make my division look good, meet our metrics, get the CEO off my back, etc. In contrast, the mantra at innovation-adept firms is: How will it add value to our customer’s life?

144If your new product and service offering truly offers greater value, customers will be willing to pay for it, it’s just that simple. They’ll be willing to endure the “costs” associated with getting up and running with your new product. They’ll be willing to take the risks to enjoy the rewards. Innovation-adept firms know that the voice of the customer needs to permeate the entire process, which means that everyone on the cross-functional team, not just the idea’s champion, lives and breathes customer value.

Product Innovation 3: Design and implement a new product development process.

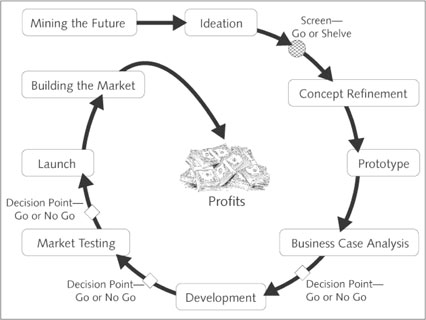

Numerous studies have demonstrated the value of having a rigorous, embedded new product development process in place, one in which all the phases are completed and each phase is evaluated by an objective committee or governance board composed of people who are not actively involved in the day-to-day project. In innovation-adept firms, new product development follows a systematic process, beginning with opportunity-sensing and moving through various stages of development, from ideation, concept, future-mining to shaping, to feasibility research and prototyping, and onward through screening, evaluation, and testing, and toward launching and selling the idea.

Typically a new product or process will have five or six checkpoints where the governance board issues a “go ahead” and gives further funding or kills the project outright. These checkpoints can range from as few as three to as many as ten (See Figure 5). GE incorporates ten into its process.

By establishing these review gates, senior management empowers development teams to do their jobs and restricts detailed financial and technical oversight to the pre-established reviews. This has the advantage of avoiding paralysis by analysis and micromanagement and decision delays, which impede progress and frustrate team members.

Robert G. Cooper, marketing professor at McMaster University, developed the “stage-gate approach” which has had a significant impact on the way many firms manage new product development. Cooper’s approach brings products to market faster at greater success rates and with major improvements in performance. Danger signs or weaknesses are detected earlier and cost overruns are aired. Launches are better planned. Stage Gate forces discussion of the product’s definition up front, and how well the project is defined prior to entering the ensuing phases has proved to be a vital factor in later success.

145Indeed, when failed products are analyzed, the invariable finding is that each functional area was busy doing its own piece of the project. There was very little communication between players and functions and no real commitment of players to the project, with participants having numerous other functional tasks underway at the same time. Stage-Gating progress, from concept to launch, makes a cross-functional approach essential.

Before Stage Gate helped make product innovation systematic, management expectations for new product risk were not quantified or communicated. Project teams were unaware of the company’s desired risk level and new product efforts ended up never being killed.

At each Gate are descriptions of what the project/team needs to prove, know, accomplish, or better understand in order to allow the project to go forward to the next stage. Stage Gates also enable a company to halt a project before it goes too far; no-go criteria are established up front, and the project team can more easily accept rejection if criteria are not met.

146Product Innovation 4: Use a learning strategy for more radical ideas.

Process-driven strategies, of which Stage Gate is the most prominent, work well for developing incrementally better products and line extensions. They work great when customers are well known and their needs and wants can be easily determined by using traditional marketing research and surveys.

Pro cess-driven strategies work less effectively when the firm is dealing with a radical product idea or a fundamentally new business model or un-proven technology. What should the criteria be at each stage? How should progress be measured, especially when there are no known customers, when the project is a drain on short-term profits, and the technology itself is un-proven?

Here, a learning-driven strategy is called for. Most managers intuitively recognize that the development process for radical new products and services must be different from that for line extensions and incremental improvements. Yet, seldom is there a deliberate process or strategy for evaluating these projects differently. All too often, academic research shows that developers were held to standards of the normal gated project evaluation process or treated in an ad hoc fashion.

According to innovation researchers, radical projects generally evolve from projects that get repeatedly axed and restored. The product’s dimensions and the market emerge gradually, as opposed to being known. Techniques such as concept testing, customer surveys, conjoint analysis, focus groups, and demographic segmentation proved in hindsight to be of limited utility and were sometimes strikingly inaccurate. Almost none had a significant impact on the development of these innovations.

“What you end up with is rarely what you started with,” says Gary Lynn, associate professor at Stevens Institute of Technology. “Since the steps are not well defined, lucky discoveries and accidental findings often send the project off in new directions. Using a regular gate process doesn’t work since it doesn’t account for the unexpected twists and turns.” Instead of the phase gate process, Lynn and others in the Innovation Movement propose an alternative process they call “probe and learn.” These scholars insist that companies can plan radical innovations, within broad guidelines, as long as they foster a spirit of team learning. By recognizing at the start that a learning strategy is called for, everyone understands the stakes much better and 147the nature of the pursuit. By agreeing on such a strategy, the organization can effectively develop products by probing potential markets with early versions of the products. Seek feedback on the probes, make adaptations, and seek more feedback—not just from customers, or potential customers, but also from suppliers, and any others who may have valuable inputs.

Like the phase gate processes, probe and learn is an iterative process, but one that allows for uncertainty. The firm enters a market with an early version of the product, learns as much as it can from the experience, modifies the product and marketing approach based on what it learns, and then tries again.

When GE Medical first launched a breast scanner, it failed miserably in the marketplace. But it did demonstrate the technical feasibility of the new technological approach: the “fan-beam” system. GE followed its breast scanner with a fan-beam-based whole-body scanner that also failed, but as before, GE’s product development engineers gained valuable insights, among them, that the marketplace was receptive to a fundamentally faster, higher resolution CT system.

Clearly, different products will require different processes. If new products and technologies are truly “new to the world,” if markets are new to the company, a strict, gated process may signal a “no go” decision prematurely. It’s best to tailor your process to fit the idea, as a one-size-fits-all approach may jettison projects with true breakthrough potential.

Product Innovation 5: Use cross-functional teams.

Cross-functional teams have become the accepted standard for new product development. But what learnings tell us how best to form one?

For starters, your new product team shouldn’t be chosen based on availability but on team chemistry and fit. Pay attention also to getting the right skill-sets as well as skill-mixes into your team. Both technical and interpersonal skills are needed among team members and a mix of maverick thinkers with those who excel at execution. Finding the right people is a key priority.

Cross-functional teaming brings the advantage of concurrent decision making. Concurrent engineering is not new—it was developed in Japan in the 1980s to speed product development. This powerful method involves every level of the company in basic design decisions, to incorporate feedback from sales, marketing, accounting, manufacturing, suppliers, customers, and assembly workers 148early in the new product development process—when it is still cheap to fix mistakes—rather than later, once millions of dollars have been spent.

Product Innovation 6: Use rapid prototyping.

Product developers for centuries have used prototypes to more ably model the real thing. In recent years, with the coming of computers and sophisticated CAD (computer-aided design) capabilities and the relative ease with which models can be “constructed,” prototyping has become an important component in producing more powerful products.

One of the chief proponents of innovation prototyping is Michael Schrage, co-director of the MIT Media Laboratory’s e-Markets Initiative, and a leading voice in the Innovation Movement. Schrage’s work explores the cultures of modeling and simulation in managing innovation and risk. In one of his books, Schrage sought to discover the secrets to creative collaboration. He thought that he was looking for the “collaborative temperament” and that he would find personality traits that make collaborators effective. Instead, his key finding was that the bedrock necessity for effective collaboration is the existence of what he came to call “shared space.”

‘“Shared space’ is the dominant medium for collaboration,” Schrage says, “because it takes shared space to create shared understandings.” And models, prototypes, and simulations enhance these vital shared spaces between collaborators, allowing them to “play” with ideas that make the proposed product better and better, and to go faster in exploring development possibilities at less cost. Seeing how a car crashes on a computer, Schrage argues, is much less expensive than crashing it against a wall in real life. “Likewise, it’s so much cheaper to have a financial simulation that shows that the mutual fund or the synthetic security you’re designing will fail in a high-interest-rate environment than to market it and have it blow up your clients’ portfolios when market conditions shift because you didn’t stress-test it.”

To Schrage, the web is “the greatest medium for rapid modeling, prototyping, and simulation that has ever been invented.” It automates and enhances information transfer, data transfer, and knowledge transfer and Schrage argues that, most important of all, it automates the prototyping process. It’s easier to play with possibilities. Suppose we change this factor?

Whatever your business, you will benefit from emphasis on prototyping early, often, and with customers. 149

Beta-Testing and Pilot Customers

Microsoft took the use of beta-testing and pilot customers to a whole new level. Before it launched its Windows 95 software, Microsoft distributed 400,000 copies of a beta version of the software, providing it free of charge to small businesspersons, individuals, and corporate computer enthusiasts for their feedback. Eager to be in on the buzz, their participation gave them bragging rights with peers. But pilot users helped the company debug harmful errors, as well as come up with value-enhancing additional features. Microsoft was thus able to tap the creativity and gain insights of a user population that mimicked the actual market. It also shifted hard-dollar costs to these volunteers since they had to put up with bugs that had yet to be patched.

The potential of your firm using beta-testing as a medium for either creating or expanding the relationship you have with a group of users-customers can be a win for both. Your company saves money on development costs and is able to launch a product that is more powerful for customers. In short, the ultimate “win-win.”

Upgrading Your Own Product Strategy

Having read this chapter, now it’s time to think about your company as it relates to product innovation, and jot down your responses to the following questions.

- How would you rate the progressiveness of your firm’s new product development process? What improvements have you introduced to the process, and how effectively have those changes increased top-line growth?

- What are the breakthrough ideas in your industry that everyone recognizes? What has been your firm’s strategy for discovering its next breakthrough idea?

- How would you characterize your industry’s clockspeed and general rate of innovation? What is your customers’ perception of the innovativeness of your products and services?

- Draw a map of your current new product development process. Ask others involved to do so also. Discuss differences, points of general understanding.

- 150What role can/might you personally play in revamping the new product development process in your company?

These aren’t just idle questions. In the 21st century, you can’t afford to wait around for happy accidents. You can’t wait for someone else to take the initiative to improve your approach to new product innovation. Nor, for that matter, can you afford to wait when it comes to generating growth strategies, and that’s a subject we’ll explore next.