5. The Courage to Choose

In 2010, Nokia’s board appointed Stephen Elop to the role of CEO. Elop, a well-known executive at Microsoft, was a bold choice. After all, Nokia, the famously Finnish company, had never had an outsider, let alone an American, as CEO. But the board members knew that the changes shaking up Nokia’s core cell phone business required doing something dramatic. At the time, interestingly, Nokia’s cell phone business still showed significant signs of strength. Apple’s iPhone had the hype, and Google’s Android operating system was experiencing explosive growth, but Nokia still dominated the market. In fact, 2010 set a high-water mark for the unit, with sales volume of more than 100 million handsets (by 2012 that number would be almost 25 million).

After six months on the job, Elop gave an internal speech describing his view of the situation. He drew on the well-traveled metaphor of the burning platform to urge the company to change radically.

A man working on an oil platform in the North Sea woke up one night from a loud explosion, which suddenly set his entire oil platform on fire. In mere moments, he was surrounded by flames. Through the smoke and heat, he barely made his way out of the chaos to the platform’s edge. When he looked down over the edge, all he could see were the dark, cold, foreboding Atlantic waters. The man had mere seconds to react [and] he decided to jump.

In ordinary circumstances, the man would never consider plunging into icy waters. But these were not ordinary times—his platform was on fire. The man survived the fall and the waters. After he was rescued, he noted that a “burning platform” caused a radical change in his behaviour. We, too, are standing on a “burning platform,” and we must decide how we are going to change our behaviour.

There’s little doubt that Nokia needed to change radically in 2011. But consider the options you have when the platform is truly on fire: get burnt to a crisp, or jump and pray. Those are not good strategic alternatives. Leaders need to have the courage to choose when the spark is lit or, even better, at the moment when it’s clear that the conditions mean that a future spark could have a meaningful impact.

When was that moment for Nokia? In hindsight, the entrance of Apple and the Android platform in 2007 was an industry watershed. But let’s go back to the end of 2005. Motorola and Apple partnered to introduce the Motorola Rokr handset. (In 2011 Motorola sold its mobility business and a treasure trove of patents to Google, which subsequently sold the unit to Lenovo in 2014.) At the time, the partnership seemed like a winning combination. Although Motorola wasn’t the leader in the handset market, its iconic Razr brand of thin devices was on its way to true blockbuster success. Apple had the shine from its booming iPod business and increasing momentum in its still core computer business. But the result of the collaboration was a compromised product that flopped in the market. Commercials, hilarious in retrospect, touted the fact that Rokr was the first handset that integrated Apple’s iTunes music software. Popular artists like Madonna and the Red Hot Chili Peppers poured into a phone booth and the voice-over intoned, “One hundred tunes in your pocket, baby.” One hundred tunes. Wow.

It was clear from the beginning that then-Apple CEO Steve Jobs was ambivalent about the partnership. Just two weeks after the commercial launch, Jobs noted publicly, “We see it as something we can learn from. It was a way to put our toe in the water.” Apple had also filed a number of patents that would enable it to create a simple, elegant phone, such as its 2004 filing (granted in 2010) for a “capacitive touchscreen.” It also was rumored to be releasing a version of its iPod music player with a screen that allowed it to play videos. The signs of what would come next were in plain sight.

Of course, companies explore new market opportunities all the time, and many hotly hyped technologies end up fizzling. The fundamental challenge for leaders is that the data showing disruption under way is always opaque. By the time it is crystal clear, it is too late to do anything about the disruption. This means that decisions can’t be guided purely by historical data, because if data drives you, you can only go backward. The following three case studies show organizations that demonstrated the courage to choose before convincing data had arrived. Then we describe the seven specific early warning signs of disruptive change.

Netflix

Legend has it that Netflix’s founding traces to Reed Hastings’s frustration borne of incurring ridiculous late fees for forgetting to return his Apollo 13 DVD. Recall that the original idea was to allow people to rent and return videocassettes through the mail. The rise of the DVD format, which could be easily mailed in slim envelopes and delivered by the US Postal Service, along with the adoption of monthly subscription fees (described in more detail in chapter 2), gave the idea additional juice. The DVD itself was clearly a cornerstone of Netflix’s initial strategy. It partnered with DVD player manufacturers (such as Toshiba and Sony) as well as movie studios to drive adoption of DVDs, and adoption rose quickly, helping push Netflix into the mainstream.

However, Hastings began quickly to plan for a world without DVDs. “From the beginning, DVD by mail was seen as a temporary play to stimulate a digital network, to build up all the other Web infrastructure, and build the brand,” he said. This isn’t ex post facto rationalization after a successful transition. Hastings said this in 2008 at a private CEO forum organized by Innosight. “It has lasted longer than we ever thought,” he added. “If you’d asked me when we started in 1997, ‘In 10 years, what percent will be downloading and streaming?’ I would have said, ‘Oh, a majority.’ And, in fact, it’s microscopic compared to DVD. And DVD continues to have lots of life. So even I overestimated the pace of change.”

The challenge in Netflix’s early days was that the commercial internet didn’t offer speeds that would provide a good user experience. But as the years passed and new technologies such as fiber, fourth-generation mobile networks, and higher-speed Wi-Fi became more ubiquitous, and as video compression techniques improved, it was time to begin the shift. In 2007, Netflix began offering free streaming to mail subscribers and then introduced a streaming-only plan in 2009.

At the time, Netflix’s core business was healthy and growing. In hindsight, moving to streaming video allowed Netflix to accelerate growth, get ahead of its competition, and expand its business outside the United States. The last point is critical. The cost of replicating Netflix’s DVD infrastructure globally would surely be substantial. The ability to essentially flip a switch and be present in a new country accelerated Netflix’s growth dramatically. It began its international expansion in 2010 and, by 2016, had expanded to almost two hundred countries, with almost half of its subscribers outside the United States.

At the time, however, none of these benefits was obvious. In fact, if anything, Hastings and team had too much courage. In 2011, Netflix announced plans to split the company into two parts. One company, which would carry the Netflix name, would focus purely on the web streaming business. The other company, to be named Qwikster, would focus only on the mail-based DVD business. But customers weren’t ready for that radical a shift, and they rebelled. The company also tried to raise prices by 60 percent. The move enraged subscribers. Netflix lost 800,000 subscribers, and its stock price dropped 77 percent in four months.

Chastened by the rare management misstep, Netflix scrapped the plan and decided to keep offering different options under one corporate roof. Hastings later admitted, “My greatest fear at Netflix has been that we wouldn’t make the leap from success in DVDs to success in streaming. In hindsight, I slid into arrogance based upon past success.”

Nonetheless, Hastings remained firm in his conviction that the future for Netflix would be streaming. “Eventually in the very long term, it’s unlikely that we’ll be on plastic media,” he said in 2011. “So, we’ve always known that, [and] that’s why we named the company Netflix and not DVDs by Mail.”

Turner Broadcasting System

Not surprisingly, you meet a cast of characters when you work with a company founded by legendary iconoclast Ted Turner, even a decade after he sold his namesake Turner Broadcasting System to Time Warner for more than $7 billion.

Return with us to 2006. Stepping into a meeting of the leadership team of Turner Entertainment Networks (TEN) in Atlanta, the first person you meet is most likely Laz. More formally known as Mark Lazarus, the charismatic leader has responsibility for TEN’s stable of channels such as TNT, TBS, and Cartoon Network. Laz (who left Turner in 2011 to become head of NBC Sports) is quick with a quip and able to incisively cut through to the heart of issues. When a consulting team member, for example, talks about not being thrilled to be in a Friday meeting with a young child at home, Laz’s eyes narrow and he says, “You do know what business you chose to get in, right?”

Next you meet the King of May, or Steve Koonin. The King bears some physical resemblance to Wayne Knight, who famously played the character Newman in Seinfeld, but one shouldn’t underestimate Koonin, who has an industry reputation for unveiling winning programs, such as the Kyra Sedgwick drama The Closer, during the vital period in May called upfronts, where networks promote shows and try to woo advertisers. To Koonin’s right you see his trusted adviser the Drama Mamma, a nickname Jennifer Dorian earned when leading a highly successful effort to come up with a motivating theme and tag line for TNT: “We Know Drama.” And let’s not forget the New York contingent: the advertising sales team led by Barry Fischer, dressed in black and waiting eagerly to get back to the center of the universe, otherwise known as Manhattan.

We swallow hard and prepare to tell this group that it needs to accelerate the pace of transforming a model that is, by all accounts, wildly successful.

A Simple, but Powerful, Business Model

First, a bit of context. Ted Turner’s insight when he founded his company in the late 1970s was that the proliferation of cable networks created the possibility to bring many more channels into individuals’ homes beyond a handful of big networks. If you flipped on one of Turner’s channels in about 2000, you were likely to encounter reruns of the police procedural powerhouse Law & Order, the bubbly comedy Friends, or an Atlanta Braves baseball game. TEN’s basic business model was to be a financial intermediary between, on the one hand, studios that had content sitting on the shelf and, on the other hand, companies that needed programming to beam from satellites or run over coaxial cables. These companies, known in industry parlance as affiliates or multisystem operators (MSOs), would pay TEN for prepackaged channels.

Anyone who watches television knows the other key component of revenue: advertising. The more interesting the content, the more viewers TEN generated, and the more advertisers would pay to reach those coveted eyeballs. In 2005, TEN’s revenue was split roughly evenly between those two categories.

TEN crunched the numbers and found opportunities to arbitrate the difference between what content owners wanted and what TEN could make selling the content to cable and satellite companies and advertisers. The simple beauty of the business model was at least one reason Time Warner happily paid billions for the company in 1996, and largely left it alone to generate substantial profits that helped offset the bleeding in its ailing magazine arm (which was spun off in 2013).

In this environment, it’s no surprise that TEN followed a linear strategy planning process: start with today’s business. Detail modest year-by-year changes in revenues and costs. Compare results to the overall target. Make modest adjustments. Repeat.

Disruptive Challenges

But nonlinear shifts emerging in the market led the team to consider a different approach. In 2005, Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim founded a company that allowed users to upload video clips. Playing on the slang word for a television set—the boob tube—they called their business YouTube. As a bizarre mix of endless cat videos and pirated professional content began to populate the site, search titan Google took notice. In May 2006—less than twelve months after the company was founded—Google snatched it up for almost $2 billion. The industry wondered whether so-called user-generated content on topics aimed at the “long tail” of users interested in arcane topics could undermine a decades-long focus on blockbuster hits.

In the third quarter of 2006, another important milestone occurred. Netflix, less than ten years old, announced that its quarterly revenues had crossed $300 million, meaning it was well on pace to become a billion-dollar business. In 2006 the popular press got wind of a rapidly growing trend among high school and college students: the use of what we now know as social networks. News Corp septuagenarian Rupert Murdoch shocked the industry by paying $580 million for social media pioneer Myspace. That move ended up being a boon to then twenty-four-year-old Mark Zuckerberg by giving him space to continue the relentless growth of Facebook.

Turner could look to its cousins in the newspaper business to get a glimpse of the future. Although newspapers still appeared to be on stable financial ground, industry analysts increasingly—and correctly—worried that the industry was about to fall off a cliff. When Knight Ridder, America’s second-largest newspaper company and the publisher of the Miami Herald and the San Jose Mercury News, put itself up for sale, few buyers stepped forward. McClatchy purchased the company in 2006 for “just” $6.5 billion (a price that in hindsight was probably 10 times too high).

These trends weren’t having a meaningful impact on Turner’s business in 2006, but Laz and team worried about the degree to which the long-range planning exercise they were working on, which looked at the business stretching out to the year 2011, was built on a solid foundation.

A Perfect Storm on the Horizon

During our meeting with the Turner executives, we shared the results of our analysis. We had built a simple model that used so-called Monte Carlo techniques to look at thousands of scenarios. Given the underlying trends in the industry, the analysis showed significant risk that TEN would encounter what we called a perfect storm: cable and satellite broadcasters would consolidate and increase their power as disruptive content offerings proliferated, decreasing the relevance of TEN’s business model. We didn’t expect that the business would disappear, but we did project a more than 20 percent chance of a wide enough miss on the long-range planning target that it could lead TEN’s corporate parent to consider drastic options, such as a reorganization or a divestiture.

TEN’s leadership agreed that these early warning signs warranted an aggressive response. Specifically, the TEN team developed five key strategic thrusts to help respond to the trends in the industry, each of which TEN would execute against in the years to come.

Invest in original content. The King of May—a prescient industry observer if ever there was one—got ahead of key industry trends. TEN struck innovative deals with personalities like Tyler Perry and Conan O’Brien. For example, after a successful ten-episode pilot on independent TV stations, TEN ordered one hundred episodes of Perry’s House of Payne, a sharp break from typical practice of ordering shows in batches of twelve to twenty-four per year. TEN earned the reputation as a place where stars had the freedom to explore creative paths and potentially keep a piece of the upside they created.

Strengthen the ability to negotiate with affiliates. As cable operators and satellite broadcasters continued to consolidate, TEN knew it had to find ways to ensure it maintained bargaining power. So it invested in a unique collection of rights to broadcast major sporting events, augmenting its relationship with the National Basketball Association, Major League Baseball playoff games, and pieces of the NCAA men’s college basketball tournament.

Do digital differently. TEN knew it needed to work hard to further its digital presence. As it built up its sports library, it also obtained rights to run the digital properties for the NBA and the Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA).

Innovate the advertising model. Traditional thirty-second spots increasingly felt like an anachronism in an age of time shifting and binge watching. In 2007, TEN began to experiment with something called TVinContext. The service offered companies the ability to match their advertisement with a particular moment in a show or movie. Imagine, for example, an exciting car chase followed by an advertisement for BMW’s latest offering. Academic research showed that such pairings had substantial impact on customer recall. Turner also began experimenting with sponsored content and in-show product placement.

Innovate the business model. TEN wanted to find ways to augment its revenue streams beyond selling commercial airtime and receiving fees from network operators. It began to explore options such as using its Turner Classic Movie brand and content library to run offline events such as film festivals or even branch into physical retail stores.

Not everything TEN did was successful, but if you flipped on one of its channels in 2011 you saw a station transformed. Instead of rerun after rerun with the occasional Braves game, you would see fresh, original programming and major sporting events. Its online presence grew substantially, and TVinContext received significant industry acclaim as TEN rolled it out.

Aetna

Harvard economist Michael Porter has made a number of contributions to the field of corporate strategy. One of the most seminal was his theory that outperformance comes from picking industry circumstances in which five forces (barriers to entry, supplier power, buyer power, competitive rivalry, and threat of substitution) support success. In 2011, health insurance companies certainly appeared to have the Porterian wind at their backs. Spending on health care had grown from roughly 6 percent of gross domestic product in the 1960s to almost 20 percent, a number that dwarfs the spending of any other country in both absolute and relative terms.

Although the 2010 Affordable Care Act, colloquially known as Obamacare, had the potential to put pricing pressures on pharmaceutical and medical device companies, it looked like a panacea to insurance companies. After all, a key provision of the act was that every American needed to have health insurance, which meant that roughly fifty million uninsured people became target customers.

In the face of all of this, Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini decided to blow the company up.

The need to do so, from the outside at least, wasn’t obvious. Before Bertolini had become CEO in November 2010, Aetna had grown through the 2007–2009 economic downturn; and with the economy picking up, in 2011, Bertolini’s first year as CEO, net income was almost 40 percent higher than it was in 2009. But Bertolini and his leadership team believed that inexorable forces would lead to long-term industry transformation. Consumers were increasingly arming themselves with information from WebMD and related websites. Wearable technology created the possibility for more-advanced diagnostics and remote monitoring. Big data analytics and behavioral economics could change the face of prevention.

As Bertolini and his leadership team sifted through these trends, three opportunities emerged. First, the company could shift from selling insurance policies and administrative services to large companies, which then provided them to their employees, to directly targeting consumers. (In a quirk of history, in 1946 the United States made employee health insurance a tax-deductible expense for companies, so many individuals get benefits from their employers.) Specifically, Aetna started creating a consumer-facing marketplace that would make shopping for health insurance as simple as buying a book at Amazon.com. Second, it could help health care providers change their fundamental pricing approach from fee-for-service to fee-for-value.

Then, for its transformation B, Aetna committed to providing new services to doctors and hospitals. Historically Aetna’s only relationship with the providers themselves was reimbursing them for service. But as technology advanced and competition increased, Aetna knew these providers needed to improve their ability to manage their costs and risks and improve health outcomes. Bertolini’s vision was to become the “Intel inside” of new provider networks via a new business it pieced together through acquisitions and investments called Healthagen. Bertolini publicly proclaimed that success would “destroy the insurance industry as we know it.”

As of the writing of this book, Aetna is well along the path of fundamentally transforming itself in five ways.

Move from the business of pricing risk to the helping members manage their health.

Drive the “retailization” of health care by empowering consumers to make informed decisions and support them in their ongoing health care journey.

Make health care more affordable while improving quality by enabling providers to take on risk and practice population health management.

Help governments and employers take better care of their beneficiaries and members by offering cost-effective access to high-quality care.

helping providers move their core business model toward fee-for-value; by 2020 Aetna expects that 75 percent of its members will be under value-based contracts.

The disruptive forces that are driving change in the health care industry promise long-term pain for insurers and other participants that try desperately to cling to yesterday’s model. As Bertolini put it, “You can be like the steel industry and go into fetal position, and hope to be the last one standing. Or you can systematically look at your whole value chain.” The courage to choose gave Aetna the time and space to experiment with different approaches, line up the right resources, get organizational alignment, and get ahead of fundamental industry change.

Bertolini says that the CEO plays a critical role in making these kinds of choices: “The CEO’s responsibility is to create a stark reality of what the future holds, and then to begin to build the plans for the organization to meet those realities.”

Early Warning Signs

Dual Transformation is the corporate equivalent of highly invasive surgery. It carries substantial risk. Not only can efforts fail, but also the organization can become distracted, creating opportunities for eagle-eyed attackers. A company should always be exploring new and different paths to growth, but those with substantial room to expand their core business without facing the existential threat posed by disruptive change should put the lion’s share of their efforts in the basics.

On the other hand, the Nokia case highlights the importance of not waiting too long. When it is obvious that you need to transform, the degree of freedom you have to successfully execute goes way down. As your core business begins to decline, you naturally have to turn an overwhelming amount of attention to mitigating the impact of that decline. The sense of urgency, sometimes bleeding into a sense of crisis, leads to significant rigidity.

Netflix, TEN, and Aetna all managed this balance well, investing early enough that they had space to explore but not so early that they got too far ahead of the industry. Each case featured a courageous leadership team, because making the case for change isn’t always obvious. In the face of all the disruptive change TEN’s leadership team was reading about, the core business was blistering hot. This is common. The seeds of transformation typically take root well outside a company’s mainstream. Early developments tend to have little or no impact on a company’s financial statements. After all, by 2005, online marketplaces (such as eBay and craigslist) and employment sites (such as Monster.com) had eviscerated the need to buy a classified ad, which, industry insiders knew, was the real profit generator for most newspapers; but many buyers did so out of habit, so newspaper companies still had healthy profit margins.

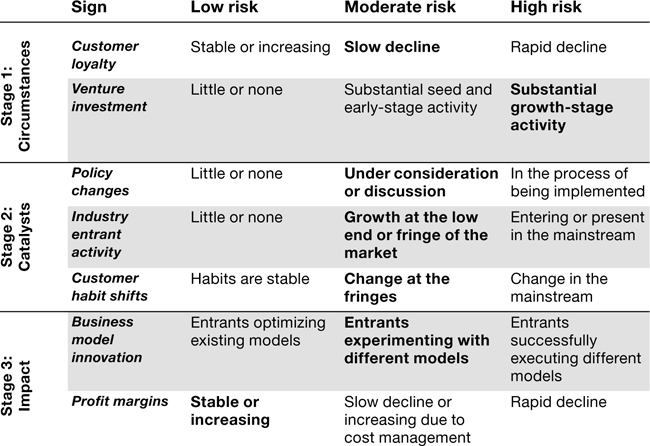

Although grounded intuition has a role to play in making decisions in the absence of convincing data, our study of historical patterns of industry disruption highlights telltale signs of impending change. Specifically, we watch for seven warning signs, which can be grouped into three stages. Next, we describe these warning signs in depth, explain how to identify them, and explore why they suggest Clayton Christensen’s fears about the future of the Harvard Business School’s flagship two-year MBA program have merit.

Stage 1: Circumstances

Forest fires are more likely, and have a more devastating impact, when dry weather has created large amounts of natural kindling. The closer together trees are, the more likely it is that a fire can spread. Similarly, certain initial conditions increase the possibility of disruptive change.

Decreases in customer loyalty, driven by overshooting.

The story of every successful company is basically the same. Try a bunch of things. Find something that works. Execute and expand.

The trick, and the essence of the innovator’s dilemma, is that doing everything you are supposed to do—listen to your best customers, produce the best products and services you can, push prices up, earn high margins, and have your stock price surge—sows the seeds of disruptive change. At some point customers say, “The last thing you gave me was more than good enough. I’ll take this new version, but the extra features don’t matter to me, so I don’t want to pay any more for it.” This is called overshooting: providing a given market tier performance it can’t use. Your television remote control probably serves as a daily reminder of overshooting. Each of those buttons can do wonderful things, but would you pay extra fees for yet another button? Probably not. When overshooting begins to set in, customer loyalty decreases, creating conditions in which an entrant can gain traction with a simpler, cheaper solution.

Significant and lasting investments by venture capitalists.

What venture capitalists are funding today can be tomorrow’s disruptive change. For example, during much of the 1980s and 1990s, many parts of the startup ecosystem focused on communications, technology, and health care. Those industries then became hotbeds of disruption in the past two decades. Similarly, in the past few years there have been significant investments in markets like data analytics, 3-D printing, renewable energy, and financial services.

Most of the individual startups will fail, of course, and the winning technologies will unfold in surprising ways. As futurist Roy Amara once noted, “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.” In the afterword, we talk more about specific industries we are watching.

Stage 2: Catalysts

The next set of early warning signs relates to triggering events that drive the transition from circumstances conducive to disruption to the beginning of disruptive impact.

Policy changes open the door to new entrants.

Governments are often portrayed as inhibitors of innovation, but that’s not fair. Many commercial innovations, including the internet, mobile technologies, and countless lifesaving drugs, have their roots in government research. That said, there is little doubt that governments can curtail both the motivation and the ability of innovators to drive disruption. When governments change the rules or focus their ample buying power in new directions, it can also accelerate, or at least influence, the pace of industry change.

Entrants emerge at the low end or market fringes with inferior-seeming solutions.

Remember when the iPhone first came out? It was a fantastic handheld computer. It was not a fantastic phone. Its battery life and call quality were pitiful compared with the performance of Nokia’s phones. Similarly, the first wave of digital disruptors in media had serious limitations. You had to wait to get your movie from Netflix. The quality of content on new media providers was laughable compared with what you would get in a well-run newspaper or magazine. YouTube primarily showed videos of cats, for goodness’ sake.

But it’s wrong to say that a disruptor is inferior. Disruptors do it differently. They trade off raw performance in the name of simplicity, convenience, affordability, or accessibility. By necessity, first customers tend not to be mainstream. Perhaps it is an undemanding customer who is happy to trade performance for price. Perhaps it is a customer who historically lacked the skills or wealth to use existing solutions, or a so-called early adopter who cares more about novelty than perfection.

The innovator uses this foothold to improve the product and service so that it meets the needs of broader customer groups, until an innovation that was once dismissed as inferior becomes perfectly adequate for wider use. When upstarts following this game-changing strategy begin to emerge, it’s time to stand up and take notice.

Customer habits and preferences show signs of shifting.

When customers begin to display lasting shifts in behavior, it opens the door for changes in the basis of competition. For example, one trend that has changed the market for business technology is the so-called consumerization of the enterprise. Employees used to have little choice except to use computers and cell phones mandated by corporate IT departments. After all, these technologies were relatively expensive and hard to integrate into corporate systems. But as companies like Apple and Dell increased usability and decreased cost, consumers increasingly showed up to work toting their favorite devices. Companies whose success was predicated on strong relationships with corporate buyers faced an onslaught of competitors that played the game in a very different way.

Companies often miss behavioral shifts because they start, not among mainstream customers, but with people at the fringes of the market. But remember, the quirky behavior that teenagers follow now (a hundred text messages a minute!) becomes mainstream only a few short years later.

Stage 3: Impact

Until this point, it is easy for incumbents to still feel safe. Venture capital investment? Maybe that will impact us in a decade, but we have time. Wacky behavior at the fringes? Interesting, but immaterial. A ground swell of changes in customer habits? OK, that’s pretty serious, but we have the resources, we have the brand, and we have the capabilities to fight back. If you respond in a serious way before you get to stage 3, you often indeed have sufficient time. But if you don’t have the courage to choose, you can expect to see the final two warning signs of change.

A viable competitor fine-tunes a disruptive business model.

Google. Amazon.com. Netflix. Tencent. All these are giants of the internet era (in case you aren’t familiar with it, Tencent is a massive digital company in China). Each is portrayed as a high-tech company. And indeed, technology is at the core of the way each creates value for customers. But what has made each of them a powerful global force is the business model it followed, which made incumbent response difficult.

We’ve described how feet on the street are no match for Google’s ad-auction model and how Netflix decimated Blockbuster’s key profit driver: late fees. Amazon.com flipped the traditional retail model on its head by optimizing its supply chain to the point that it receives money from customers before it places an order with a supplier, giving it negative days working capital in its core retailing business.

For its part, Tencent zigged where most similar companies zagged. The dominant business model for online providers is to build audiences and then sell advertisements. Tencent built a huge audience via its free QQ messenger service, but it built its business on microtransactions, in which customers buy credits to advance in a simple game or add a scarf or hairstyle to their messenger’s avatar. By 2015 the company had annual revenues of more than $10 billion, more than 75 percent of it from these kinds of small purchases. Tencent further diversified its business model by integrating payments into its WeChat messaging platform. By the end of 2016 Tencent had emerged as Asia’s most valuable publicly traded company.

Technologies can be copied, but business models persist. When a competitor develops a model that decimates a heretofore dominant profit stream, allows it to prosper at price points the market leader can’t match, or involves an integrated network of unique suppliers and partners, disruption is nigh.

Slowing revenue growth is coupled with increased profit margins as leaders exit volume tiers and cut costs.

Perhaps most paradoxically, when incumbents begin to feel the pain from disruption, it doesn’t always feel very painful. The slowing growth that comes with overshooting feels like the natural result of an industry maturing. Emerging disruptors grow in a seemingly disconnected market, and, if they pick off customers, often they are ones the incumbent doesn’t care much about anyway. Of course, slowing growth at the high end, coupled with customer flight in volume tiers, sets off financial alarm bells that draw out the cost cutters. Analysts applaud the focus on efficiency, setting off improvements in the stock price that convince leaders that more systematic action is unnecessary. But when the company runs out of costs to cut, and can’t figure out how to grow the top line, the applause turns to dismay as the full force of disruption becomes increasingly obvious.

Table 5-1 shows the three examples in this chapter along with some of the early signals that helped leaders at Aetna, Netflix, and Turner demonstrate the courage to change. Note that in each case the respective company responded before a truly disruptive business model emerged with corresponding negative financial impact.

How to Spot Early Warning Signs

The seven signals of disruptive change are straightforward, but they aren’t always easy to see. We have five tips to help you spot early warning signs.

Go to the periphery.

The periphery is the edges or fringes of your industry. It might include extreme customer groups, such as those in particularly demanding circumstances or those that have demonstrated they can be satisfied with very little. It might include people historically locked out of the market because they lack skills, wealth, or sophistication. It might include the teenagers and hackers who love to play. In a business-to-business context, it might include smaller businesses, or businesses in poorer markets. It certainly operates in global innovation hot spots where new businesses incubate and early adopters proliferate, such as Silicon Valley, Shanghai, Berlin, and London. As legendary science fiction writer William Gibson famously noted, “The future has already arrived. It is just not very evenly distributed.”

Early signals of disruption at three companies

| Early warning sign | Aetna (2010) | Netflix (2008) | Turner (2007) |

Change in customer loyalty |

Not material, but insurance providers generally are not “loved” brands |

Not material |

Channel proliferation driving decrease in ratings |

Venture funding |

Health care IT had been funded aggressively for 10+ years |

New content models had been funded aggressively |

New content models had been funded aggressively |

Policy change |

Affordable Care Act |

Nothing material |

Nothing material |

Emergence of disruptors at the fringes |

Google and Microsoft attempting to create electronic medical records, new online-only insurance models |

YouTube, Hulu, and other online streaming services emerging |

Netflix, YouTube, and Facebook present but nascent |

Customer habit change |

Customers using web to diagnose; postrecession cost consciousness |

Fringe customers with high bandwidth watching on laptops and phones vs. TVs |

Fringe customers with high bandwidth watching on laptops and phones vs. TVs |

Competitor business model |

Not yet viable |

Not yet viable |

Not yet viable |

Financial impact |

Not material |

Not material |

Not material |

Pay Attention to Small Things.

During a 2005 presentation at Turner, coauthor Scott Anthony highlighted the disruptive potential of YouTube. One audience member commented, “YouTube is great, but if you add up every video that anyone has ever watched on it, it is less than the lowest-ranked prime-time show on a Tuesday night.” True—in 2005. Less true in 2010. And certainly not true in 2016.

Anything that is growing rapidly bears attention. Karl Ronn, a Procter & Gamble executive who helped that company launch three billion-dollar disruptions before leaving to create his own disruptive ventures, told us his rule of thumb: “Anything that has doubled its size is a potential disruptor, regardless of size.” Those fast-growing companies, he noted, “are running the test market we should have run. This is a simple way to not ignore small stuff.”

Not every early-stage development pans out, of course; Murdoch’s bet on Myspace serves as only one example. But identifying peripheral developments early through the disruptive lens maximizes your chances of identifying a serious disruptive change with enough time to respond appropriately.

Think about What Could Happen in the Future, and Not What Is Happening Now.

For a range of psychological reasons, it is hard for even the most sensible executive to point out the fatal flaws in what a company is doing now. But if you step out into the future, executives can take a more clinical perspective. For example, TEN put itself far enough into the future that no one felt a personal risk in pointing out that there might be cracks in the business model.

The right range depends on your industry. Consider a multibillion-dollar defense company we advised. The company had just lost a critical contract to a rival, but its five-year growth plan still looked solid, because development and procurement cycles in the defense industry stretch over decades. When the company expanded the range of its growth projections from five to fifteen years, a mission-critical problem came into view. Changing customer needs due to geopolitical forces, defense budget crunches, and technological disruptions meant that the defense company faced a massive revenue shortfall that would challenge the organization to transform itself and create new growth.

Involve Outsiders.

A telling example of how hard it can be to identify problems in your current business comes from an experience of coauthors Clark Gilbert and Mark Johnson at the Harvard Business School in the early 2000s. The two were participating in a colloquium about responding to disruptive change. Leadership teams from a half-dozen organizations, such as Intel, Kodak, and the US Defense Department, attended the event. Fitting the HBS theme, researchers wrote twenty-page case studies describing a disruptive development in the respective industries. Companies had to listen quietly while their case study was discussed. Here’s how Gilbert describes it.

I thought this was going to be the most boring event ever. We basically had written five versions of the same case. But it was remarkable. Every time when the discussion ended and the company could comment, they would patiently explain how they were different. Kodak could instantly see Intel’s problem with low-end microprocessors. The defense guys could see Kodak’s challenge with digital imaging. But none of the companies could see their own problem. It really showed me how hard it can be to identify your own problems.

Assess the Cost of Inaction.

TEN’s analysis focused on how its business could erode if it didn’t change and if disruptive developments continued. Most companies take the opposite approach. They consider various response strategies, often building detailed spreadsheets to project the required investment and impact of each strategy. A popular approach involves calculating the net present value (NPV) of an investment proposal by discounting future cash flows using an agreed-upon rate. A basic rule of finance is that positive NPV projects should be approved, and negative ones should be rejected. However, most people who follow this technique make an implicit assumption that the base case is zero, an assumption that biases them against doing projects that require up-front investments and might not generate returns until a few years into the future. When you recognize the cost of inaction, it raises the imperative of response.

Is Christensen’s Fear Justified?

In 2014, Clayton Christensen gave the annual management lecture for the Singapore Institute of Management to a thousand-person audience. He described the disruptions taking place in education, saying he was worried about the future of his employer, the Harvard Business School. In particular, he questioned the long-term viability of the school’s core two-year MBA offering. He ended his speech by saying, “I will pray for Singapore’s future if you will pray for the Harvard Business School’s.”

Are there early warning signs of impending disruptive change that could affect an institution like HBS? The short answer is yes. Table 5-2 is a simple tool we use to assess the presence of the warning signs described in this chapter (this tool and other key tools appear in the appendix and at dualtransformation.com). It provides qualitative choices for each of the seven warning signs to help identify how pressing the threat is.

TABLE 5-2

Tool to assess the warning signs of disruption

Let’s look at each row.

Changes in customer loyalty (moderate risk). The number of people signing up to take the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT), a prerequisite for admission to a two-year MBA program, declined by 33 percent between 2009 and 2015. That’s at least one sign that customer loyalty is decreasing.

Venture investment (high risk). It’s hard to get precise figures on venture investment, but at least two sources suggest that US venture capitalists invested about $2 billion in education-related startups in 2014, up from less than $500 million in 2009.

Policy changes (medium risk). As the cost of higher education has risen substantially over the past few decades, a growing number of students are graduating with crushing debt burdens. Politicians have taken notice, and although major reform hasn’t happened, there are signs it could be coming.

Industry entrant activity (medium risk). Over the past few years a number of new models have emerged as viable ways to provide business education. This includes platforms that offer access to massive online open courses (MOOCs) and improvements in employer-driven education programs.

Habit change (moderate risk). Online education clearly involves a set of habits distinct from traditional classroom-based education. These habits haven’t crossed over to mainstream behavior, but as more children grow up digital, the teaching paradigm could transform.

Disruptive business model (moderate risk). Emerging players in the market are clearly experimenting with radically different business models, an action that could present significant challenges to HBS and other mainstream schools. These business models haven’t yet shown commercial viability, but they could do so in surprisingly short order.

Financial results (low risk). The last time we checked, Harvard’s endowment still looked pretty solid. In 2014 HBS launched a $1 billion, five-year fund-raising campaign. The campaign quietly started in 2012 and had already raised $600 million when the official announcement came. By mid-2016, HBS announced that it had raised $925 million.

Overall, there is reason to worry. And there are reasons to be encouraged that the school that houses the father of disruption is indeed responding. Harvard’s publishing arm has a corporate learning arm that provides customized education programs to mid-level managers at corporations, using a blend of case studies, online modules, and web-based lectures. In 2013 it created a separate group called HBX to develop online courses. In 2014 it rolled out a three-week program that teaches basic business skills, such as financial analysis. In 2015 HBX launched an immersive version of Christensen’s class that can be taken by individuals or teams at companies for less than $2,000 per person.

Time will tell, of course, whether Christensen’s prayers are answered.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

By the time the platform is on fire, dual transformation is next to impossible. Leaders need to follow the lead of Reed Hastings at Netflix, Mark Lazarus at Turner Entertainment Network, and Mark Bertolini at Aetna and summon the courage to choose to transform before the need is obvious. Keep your eyes open for the seven early warning signs of disruptive change: decreases in customer loyalty, spikes in venture capital investment, policy changes, fringe entrants, changes in customer habits, formation of new business models, and a shift of financial focus from revenue growth to margin protection. To spot these signals, live in the periphery, pay attention to anything growing rapidly, plant yourself in the future, involve outsiders, and estimate the cost of inaction.