1. Disruptive Shock Waves and

Dual Transformation

The year is 1975.

The Boston Red Sox lose in the World Series in heartbreaking fashion, again. The disco era begins, with the Bee Gees’ “Jive Talkin’” and Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Shining Star” topping global charts. In the town of Rochester, New York, a young engineer named Steve Sasson creates a disruptive technology that allows a consumer to capture what we now call a digital image. The device is as big as a toaster and takes more than twenty seconds to capture an image, but the seeds of disruption are sown. Far from working for an upstart company, Sasson works for Eastman Kodak. At the time the company dominates the silver halide chemical film market, with an 80 percent share and a 70 percent gross profit margin. And now it has a prototype for a camera that uses no film.

What happens next?

You probably know the story. Kodak invests heavily in the new technology, introducing its first digital camera in 1990. By 2000 it emerges as one of the leading digital imaging producers. In 2001 it makes the bold move to purchase an emerging photo sharing site called Ofoto. Embracing its historical tag line, “Share memories, share life,” Kodak rebrands Ofoto as Kodak Moments, transforming it into the leader of a new category called social networking, where people share pictures, personal updates, and links to news and information. In 2010, it attracts a young engineer from Google named Kevin Systrom, who takes the site to the next level. By 2015 Kodak Moments has hundreds of millions of users. Kodak still sells film to niche markets (and makes nice profits doing so), but the company’s center of gravity has clearly shifted to social networking. The company deftly manages the transition and emerges from a potentially disruptive shock a different, but vibrant, organization.

Wait—that didn’t happen.

Kodak did indeed invest in digital imaging and did indeed buy Ofoto, but instead of turning it into a vibrant social network Kodak focused on getting more people to print more pictures. It sold the business in 2011. It did indeed invest heavily in digital technologies; Sasson’s quotable line in 2008 that management’s response to his technology was, “That’s cute, please don’t tell anyone about it” was also cute but not particularly accurate. But seemingly Kodak was never able to fundamentally shift its business model, and as silver halide film began its inevitable decline, so too did the company. Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2012.

It’s a sad story of lost potential. The American icon had the talent, the money, and even the foresight to make the transition. But instead it ended up the victim of the aftershocks of a disruptive change.

A Transformational Year for Media

On June 17, 1994, Americans are glued to their television sets watching O.J. Simpson, a charismatic retired football player who had appeared in movies and television commercials, riding in his white Ford Bronco while being chased by police. Simpson is accused of violently murdering his ex-wife and one of her friends, and the combination of violence and celebrity makes it catnip for viewers. This is the first time that television news producers, most notably Turner Broadcasting’s Cable News Network, break from actual news to cover second-by-second minutia of something so voyeuristic. It was a seminal moment in the media industry, and its effects are still being felt.

An even more important event took place later that same year when Marc Andreessen and his team introduced a beta version of the Netscape browser. Since the late 1960s, academics and defense officials had been experimenting with using a distributed network of computer connections to communicate and collaborate. The Netscape browser—coupled with Tim Berners-Lee’s invention of HyperText Markup Language (HTML) universal resource locators (URLs), along with a range of complementary innovations—allowed even the layperson to ride the so-called information superhighway. The disruptive effects of this internet-enabling technology reshaped the media business. The first to feel its effects were newspapers. Historically the scale economics of the printing press created significant barriers to entry, resulting in effective natural monopolies in many markets; most US cities had only one or two highly profitable papers. The rise of the commercial internet destroyed this business, with most newspaper companies decimated by 2000.

Well, not exactly. Certainly the newspaper companies felt some pain during the 2000–2002 US recession, but the years from 1994 through 2007 were actually quite good for most newspapers. Although the internet was stealing eyeballs, circulation remained relatively stable and advertising revenue continued to grow. The rise of classified-ad killers—such as craigslist (which offered free listings for apartments, jobs, and other, less savory things) and eBay—were nuisances. But when two of us (coauthors Clark Gilbert and Scott Anthony) presented a talk at a Newspaper Association of America meeting in Miami in January 2005, the dominant sentiment was that the industry had taken the best punch the internet could throw and still stood tall.

As legendary investor Warren Buffett likes to say, when the tide goes out you see who is swimming naked. The next US recession, in 2007–2009, showed the industry’s precarious position. From 1950 to 2005, industry advertising revenue grew from roughly $20 billion to $60 billion. By 2010, the market had fallen to $20 billion. Put another way, fifty-five years’ worth of advertising growth was eviscerated in a handful of years. Companies went bankrupt, jobs were lost, with the few remaining players staggering to find a sustainable path forward.

A Transformational Year for Mobile Handsets

In 2007 the Boston Red Sox, miraculously, celebrate their second World Series championship in four years after an eighty-six-year gap between their last two. Disney’s Pixar Animation Studios releases a movie about a rat who is also a chef, grossing more than $600 million worldwide, earning widespread critical acclaim and demonstrating why Disney paid Steve Jobs more than $7 billion in 2006 to acquire John Lasseter, Ed Catmull, Woody, Buzz, Nemo, Luxo Jr., and the rest of the Pixar team.

There were two darlings in the mobile handset industry. Nokia had emerged from bruising battles with Motorola and others as the clear market leader, with market share three times as big as that of the nearest competitor. In November, Forbes ran a cover story proclaiming, “One Billion Customers: Can Anyone Catch the Cellphone King?”

Um, yes. But not overnight. In fact, if you were an investor in Nokia, 2007 was indeed a very good year for you. Whereas the S&P was up by 5 percent that year, Nokia’s stock surged by 155 percent, trumping another industry competitor heralded for its innovation prowess: Canada’s technology darling Research in Motion (RIM), best known for its BlackBerry handset. RIM’s stock almost doubled during 2007. In what turned out to be a prescient interview with CBC in April 2008, RIM’s co-CEO, Jim Balsillie, said, “I don’t look up too much or down too much. The great fun is doing what you do every day. I’m sort of a poster child for not sort of doing anything but what we do every day . . . We’re a very poorly diversified portfolio. It either goes to the moon or crashes to the Earth.”

And crash both Nokia and RIM did.

In January 2007 Steve Jobs announced, and in June Apple launched, the iPhone. Dubbed the “Jesus phone” by worshippers, the phone created a media firestorm and immediately started showing up in the hands of celebrities. In November, Google, along with a range of handset manufacturers, formed the Open Handset Alliance, powered by Google’s Android operating system. Android’s origins trace to a $50 million acquisition Google made in 2005 of a young startup that had hot technologies as well as Andy Rubin, a noted talent in the wireless space. Google’s hope was that by making it easier for users to access the internet on mobile phones, it could expand its core advertising business.

In 2013, Nokia sold its handset business to Microsoft for more than $7 billion. Eighteen months later, Microsoft took a write-down of roughly $7 billion. RIM, renamed BlackBerry, saw its stock drop close to 95 percent from the 2008 Balsillie interview to 2015.

Kodak’s digital disruption took almost forty years to fully play out. Newspapers had about a dozen years of life after the internet shock. Nokia and RIM had only five years before great businesses painfully built over decades were ripped apart.

And thus the innovator’s clock accelerates.

In the HBO sword-and-sorcery series Game of Thrones, and the books by George R.R. Martin that inspired the show, the gritty Stark family has a saying: winter is coming. It isn’t winter that’s coming to your boardroom. It is disruption. Disruption is coming. And it is coming at an unprecedented pace and scale.

The Circle of Disruption

Yet there’s something oddly comforting in the industry case studies. It’s the way of capitalism, after all. A disruptive change hits a market, making what used to be complicated simple, and what used to be expensive affordable. Lumbering giants move too slowly, toppling under their own weight. Innovative upstarts, run by young, charismatic entrepreneurs, embrace the newness of the technology, creating new business models and indeed new organizational forms. The disruption breaks open a historically constrained market, bringing new solutions to millions, if not billions, of people. Then enterprising upstarts become lumbering giants, destined to be felled by the next generation of entrepreneurs. Cue the montage, play Elton John’s “Circle of Life” from The Lion King, and pass the popcorn.

Of course, if you’re a top executive in one of the companies confronting this kind of challenge, it is anything but entertaining. In fact, we believe that it is the greatest challenge facing leaders today. Creating a new business from scratch is hard, but executives of incumbents have the dual challenge of creating new businesses while simultaneously staving off never-ending attacks on existing operations, which provide vital cash flow and capabilities to invest in growth. The hastening pace of disruptive change means leaders have precious little time to respond. In fact, the time when leaders need to be most prepared for a change is right at the moment when they feel they’re at the very top of their game.

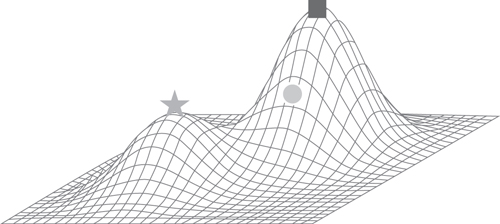

One metaphor that we’ve found helpful to frame the challenge is what’s known as a fitness landscape, borrowed from the field of population ecology. A fitness landscape is a representation of a topological map, with the height of a given hill showing its general attractiveness. Study the map in figure 1-1. Imagine you run the company represented by the square at the top of the highest mountain. You’ve done it. You’ve left your competition (represented by the circle) in the dust. You’re the top of the heap. The monarch of the mountain. From your commanding heights you can clearly see a new, disruptive upstart taking root (represented by the star). From your vantage point, you can see how small that hill is. It is inconsequential.

Consider your strategic choices. You are in fact sitting on what is called a “local maximum.” Any strategy looks inferior to the one you’re currently following. Put in simple terms, there is no direction to go but down.

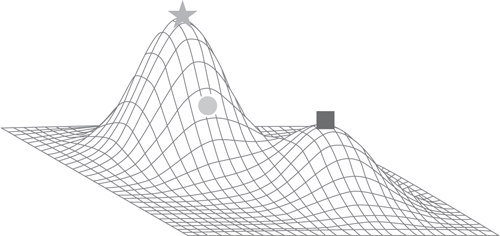

This phenomenon paralyzes leaders who own a position atop a historic hill. Unfortunately, the landscape is not static. In fact, disruption rearranges the strategic topography. You wake up one day and the landscape looks like the image in figure 1-2. Consider your options now. The disruptor (still a star) is too big and powerful to attack head on, so your best chance is to establish a foothold on its hill (the circle). But that strategy, and any other, looks materially worse than what you’re currently doing. Your square sits at the top of the hill, although it’s a much smaller one. Once again, there’s no direction to go but down.

FIGURE 1-1

Industry topography, before disruption

Industry topography, after disruption

This is tough stuff. And this is only about the fundamental decision to change strategy. Any leader who has gone through a reorganization or reinvention will tell you that, as hard as it is to decide to change, it is easier than actually making the change.

The term often used to describe what happened to Kodak, newspaper companies, and Nokia is creative destruction. The phrase is generally credited to economist Joseph Schumpeter from his landmark book Capitalism, Socialism and Demography. In that work he vividly described the “gale of creative destruction” that tears down established institutions. Schumpeter described the destructive power of this gale, coupled with the innovative creation spurred by entrepreneurs, noting, “[T]he problem that is usually being visualized is how capitalism administers existing structures, whereas the relevant problem is how it creates and destroys them.”

The emergence of a new hill creates tremendous growth for its creator. However, while we celebrate these vibrant gains, let’s stop and consider the losses when the transition involves the rise of a new company and the death of an old one. Thousands of jobs, if not tens of thousands, are displaced. Communities that grew up around enterprises are torn apart. Tens of thousands of years of accumulated know-how are lost. This kind of creative destruction carries a heavy transaction tax.

What if, instead, leaders could harness the underlying forces behind these kinds of changes to power new waves of growth for their companies? More specifically, what if a company sensed the gale coming early enough and built a wall to protect its core business? Or, even better, what if it built a wind turbine to harness the energy in the gale?

This book teaches you how to do just that.

Dual Transformation and the Disruption Opportunity

There are classic examples of companies that have risen to the challenge of disruptive change. Imagine IBM in the 1990s moving from products to services, or Apple during Steve Jobs’s second run as CEO moving from desktop computers to mobile devices and entertainment. There are other stories of companies that made dramatic shifts from one business to another, such as Nokia moving from rubber boots to mobile phones, or Marriott moving from a root beer stand to hotels.

We occasionally draw on these business classics, but our primary focus is on fresh, recent stories, many of which we have experienced firsthand either as advisers or as practitioners. Our experience allows us to present, for the first time, a detailed perspective of what strategic transformation looks like and, more important, what it feels like as you go through the journey. It’s like a virtual GoPro camera recording corporate leaders as they confront the hardest challenge in business.

Our bedrock case study comes from coauthor Clark Gilbert’s firsthand experience leading a transformation at Deseret Media. The Deseret (Utah) News is one of America’s oldest continually published newspapers, tracing back to 1850. Ultimately owned by the Mormon Church (which also owns the local KSL television station), the paper historically competed in Utah with The Salt Lake Tribune under what is known in the industry as a joint operating agreement, wherein the two companies share facilities and printing presses but have independent journalists, brand positions, and so forth. As the number 2 provider in its market, Deseret Media was hit particularly hard by the disruptive punch of the internet; between 2008 and 2010 the Deseret News lost nearly 30 percent of its print display advertising revenue and 70 percent of its print classified revenue.

In 2009, Gilbert—who had done his doctoral research at Harvard on the newspaper industry and had consulted to the industry before he became head of online learning at Brigham Young University-Idaho—was asked to launch Deseret Digital Media, a newly formed organization that contained Deseret Media’s collection of websites. In May 2010, Gilbert was also appointed to the newly created position of president of the Deseret News, giving him control of both the legacy business and its new growth digital ventures. Industry insiders sneered. Gilbert, after all, was an academic. Now he would learn what the real world looked like.

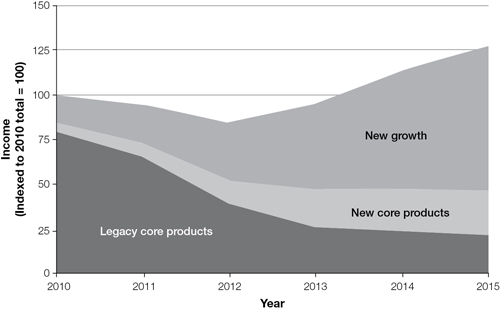

Five years later, however, Deseret Media had a vibrant print publication, including a national weekly that was one of the fastest growing publications in the United States. It also had built an impressive array of quickly growing digital marketplace businesses tied to its KSL classifieds products that collectively produced more than 50 percent of the organization’s combined net income. These digital businesses shared brands, content, and a few other resources with the core business but largely functioned autonomously. Deseret Media had revitalized its historical core business while simultaneously pioneering the creation of a new hill on the media landscape. By the time Gilbert left in 2015 to become president of BYU-Idaho, net income at Deseret, in the midst of an industry in free fall, was up by almost 25 percent from 2010. While the specific details on figure 1-3 have been stylized to protect company confidential information, the picture is clear: a repositioned, stabilized core business and a quickly growing new growth business.

FIGURE 1-3

Deseret net income

Rather than detailed insights about specific media business models or new revenue streams, Deseret’s success, according to Gilbert, is attributed to organizing the company to adapt to two very different types of change. Rather than view change as one monolithic transformation process, Gilbert organized the company into two parallel change efforts: one to reposition the core newspaper business, and another to unlock new growth in digital markets. (Although Gilbert is an author of this book, occasionally we feature direct quotations from him to amplify key messages.)

We call this change effort dual transformation. Please note that our use of the term transformation is different from the common lexicon. Transformation often serves as shorthand for any big change, whether it’s a company dramatically downsizing or a Hollywood actor gaining or losing significant weight for a role. Typically, when people use the word it is akin to what author Bill Simmons describes as “the leap” in professional basketball: a player like Stephen Curry goes from being a good player to being otherworldly, and his team, the Golden State Warriors, “transforms” into a title contender. This is a case of changing from mediocre to good, or from good to great. It is not the transformation we are describing here.

Rather, the idea of transformation in this book is materially different: businesses are fundamentally changing in form or substance. A piece of the old, if not the essence, remains, but what emerges is clearly different in material ways. It is a liquid becoming a gas. A caterpillar becoming a butterfly.

We call the process we describe a dual transformation because it requires two transformations and not one. In response to a disruptive shock, executives must simultaneously reposition their traditional core organization while leading a separate and focused team on a separate and distinct march up a new hill.

Look again at figure 1-3, and imagine the leadership challenges facing Gilbert and his team at Deseret. New growth businesses were relatively small in 2010. How can you convince great external talent to come work for a small piece of a languishing incumbent, when the literature describes how hard it is for incumbents to innovate? In 2012, legacy core products looked to be in almost free fall. New products related to the core were beginning to grow, but how can you convince top talent that there remains a viable future in a rapidly diminishing business?

Similarly, in that year even though the new growth engine was beginning to hum, Gilbert was three years into his tenure and hadn’t turned a corner. How can you convince board members and other key stakeholders that the corner will come? And along the way, the newspaper business and the digital business are constantly in conflict, fighting for attention and assets. Which side should a leader back, and when? And at the end of the story, when the organization clearly has changed—with new growth now the dominant source of income—how do you communicate your new identity while respecting your past one?

There’s no doubt that the kind of existential change required to rise to the challenge of disruption is the hardest challenge a leader will ever face. It requires looking deep into, and sometimes reimagining, the very soul of the organization. You have to make tough choices to curtail investment in yesterday’s core. There will almost undoubtedly be cost cuts, some of which will be significant. In some cases, you may ultimately shut down or spin off large components of your company’s legacy business. You will have to decide to place big bets on future markets in the absence of convincing data. You will have to pull recalcitrant employees, shareholders, board members, and stakeholders along, convincing them not with data but with vision and storytelling.

At the same time, it’s the greatest opportunity a leadership team will ever face. The disruption that frequently rips an incumbent apart almost always results in net market growth. Did people stop taking pictures because Kodak went bankrupt? Of course not. The best estimates suggest that the world takes at least ten times as many pictures as a generation ago, because it is simple and affordable (those of us who live in Asia and see what Filipinos can do with selfie sticks think the number is markedly higher). Similarly, no one stopped consuming news because a local newspaper went out of business. The amount of content produced and consumed has gone up exponentially. Companies certainly haven’t stopped advertising even as newspaper page counts have gone down. People didn’t stop using mobile phones when the former market leader exited the business. By 2020, forecasters project that there will be more than six billion people with what used to be considered supercomputers sitting inside their pockets.

Disruption opens windows of opportunity to create massive new markets. It is the moment when the market also-ran can become the market leader. It is the moment when business legacies are created.

And getting started requires remembering nothing more than A, B, and C.

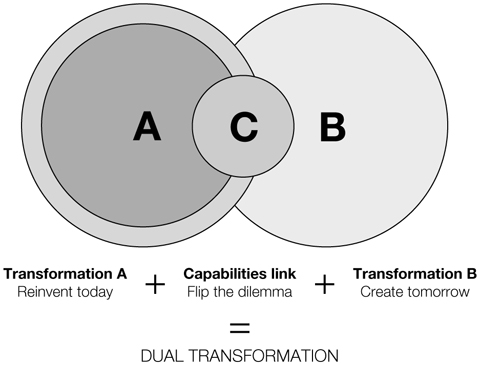

The Dual Transformation Equation: A + B + C = Δ

When you take your first algebra class, you’re introduced to the Greek letter delta. The capital form of the fourth letter in the Greek alphabet, Δ, also serves as shorthand in math equations for change. The kind of change we’re talking about here is indeed a very large delta. Achieving that change requires following this formula:

A + B + C = Δ

Here’s how it breaks down.

A = transformation A. Reposition today’s business to maximize its resilience.

B = transformation B. Create a separate new growth engine.

C = the capabilities link. Fight unfairly by taking advantage of difficult-to-replicate assets without succumbing to the sucking sound of the core.

The formula’s simplicity belies the complexity of its execution. None of the stories we tell in this book are perfect. Sometimes success involves avoiding a worse outcome suffered by a competitor. For example, both Barnes & Noble and Borders had to confront the fact that online retailing threatened the vitality of their historical book retailing model. Barnes & Noble sought to reposition its stores from bookstores to destinations featuring cafés, and to build new growth in electronic readers. Borders, in contrast, doubled down on running its current model more efficiently.

Barnes & Noble struggled mightily, with sales in its core sagging and its Nook reader falling behind multipurpose tablets offered by companies such as Apple, Samsung, and Amazon.com. From the launch of the Nook in June 2010 to June 2016, Barnes & Noble’s stock dropped 4 percent while the S&P 500 almost doubled. Although that doesn’t sound like an inspirational outcome, it is better than what happened to Borders, which went bankrupt in 2011.

We confidently predict that some of the in-process efforts described here will struggle or even stall. But we also confidently assert that, even so, these companies were very likely better off for having started the journey.

Xerox’s Dual Transformation

A case example of an iconic American company that staved off disruptive threats and reinvented itself between 2000 and 2015 provides further color about each letter in our equation and also demonstrates both the opportunities and the challenges of dual transformation.

Xerox was founded in 1906 as The Haloid Photographic Company. Its modern history traces to a 1946 decision by CEO Joseph C. Wilson to commercialize a process the company had invented to print images using an electrically charged drum and dry powder toner. It branded the process xerography, launched its revolutionary plain paper photocopier in 1959, and changed the name of the company to Xerox in 1961. By the 1970s Xerox had become an American icon, with its name becoming a verb synonymous with photocopying.

The legendary Xerox research laboratory pioneered many of the technologies that enabled the personal computer era, including the graphical user interface, the mouse, and networking. Unfortunately, those technologies were largely commercialized by other companies, such as 3Com and, most notably, Apple, whose cofounder Steve Jobs was famously influenced by a visit to the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in 1979. At the turn of the century, Xerox hit the skids. Lower-cost competitors from Asia eroded the margins and share of Xerox’s copiers. The rise of the internet and electronic communications raised questions about the long-term potential of paper-based copiers and printers. As the company’s stock price sagged and revenues contracted, analysts began to wonder whether its heavy debt burden meant it would face the prospect of bankruptcy. Xerox stock, which tripled from 1995 to 1999, decreased more than 90 percent from June 1999 to December 2000.

Under the guidance of first Anne Mulcahy and then Ursula Burns, Xerox’s fate turned. Burns ran an aggressive program to reconfigure Xerox’s historic core business, simplifying product lines and outsourcing noncore functions. The resulting core was significantly smaller, but cash flow was positive and, critically, stable. This is transformation A: repositioning today’s business to increase its resilience. Chapter 2 details how success with transformation A starts with determining the customer problem, or the job to be done, around which you should reposition your core and then innovating your business model to deliver against the job, measuring and tracking new metrics that reflect the new model, and burning the boats by executing rapidly.

In parallel, Xerox began to experiment with new service lines designed to optimize repeatable business processes. It built a line of businesses that produced hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, and then in 2009 it spent more than $6 billion to buy Affiliated Computer Services (ACS), a company that specialized in business process automation. This is transformation B: creating a new growth engine. Whereas transformation A is often defensive in nature, the disruption that forces it opens opportunities to solve new (but related) problems in different (but related) ways. Put another way, the disruptive forces that threaten to rip apart today’s business create conditions to build tomorrow’s business.

A core threat to Xerox was commoditization in its core printer and copier business, a phenomenon driven by globalization and the rise of the internet, which dampened demand for physical solutions. Those same forces created new demand for and allowed Xerox to assemble a portfolio of service offerings under the brand Xerox Global Services (XGS). Chapter 3 describes how succeeding with transformation B requires three actions: identifying a historically constrained market that disruptive forces will open, iteratively developing a business model to win in that market, and acquiring or hiring complementary capabilities to compete successfully against new and emerging competitors.

Xerox: The Capabilities Link

Now for the C part of the equation, the capabilities link. In 1997, Innosight cofounder and Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen released The Innovator’s Dilemma, describing how well-run incumbents fail in the face of disruptive change. The capabilities link flips the dilemma. It allows a company to strike a balance wherein it leverages just enough capabilities to gain an advantage versus other competitors, but not so many capabilities that by definition its ability to do something new is constrained.

Xerox did not perform unrelated diversification. Rather, it combined ACS with the Xerox brand, salesforce, and R&D capability to accelerate its growth. For example, Xerox researchers applied advanced analytics software to manage the E-ZPass toll collection system in the East Coast of the United States. Xerox R&D resources developed simple cloud-based tools to make document services accessible to a wider base of customers, creating new products that, for example, enable banks to improve the mortgage approval process or law firms to increase analytical capabilities. This is the capabilities link, and chapter 4 will describe how leaders need to do three things to successfully create it: carefully select critical capabilities, strategically manage the interface between the core and the new, and actively arbitrate when disputes arise.

Xerox: The End and the Beginning

Xerox’s effort to reposition its legacy business not only extended the life and profitability of the copier business but also enabled the company to invest in and ultimately take a new hill in the emerging process-outsourcing business. By 2012, Xerox had climbed back to the $21 billion revenue mark that it had achieved before the transformation process began. Most important, services outstripped technology for the first time, generating the majority of revenue for the enterprise. Xerox grew to become the world’s second-largest pensions and benefits administrator. Total employment rose to almost 150,000, and its stock price increased fourfold between 2000 and 2015.

But the forces of industry change are relentless. Revenues dipped from $21 billion in 2012 to $18 billion in 2015, and Xerox’s stock fell by almost 50 percent from January 2015 to January 2016. Later that year, influenced undoubtedly by pressure from activist investor Carl Icahn, Xerox announced plans to split into two companies: a business process-outsourcing company called Conduent, with 96,000 employees and $7 billion in revenue; and a copier and printer business, with 39,000 employees and $7 billion in revenue. The two offshoot businesses are individually more vibrant than either would have been a decade ago but no doubt will again confront the challenge of disruptive change in their respective markets.

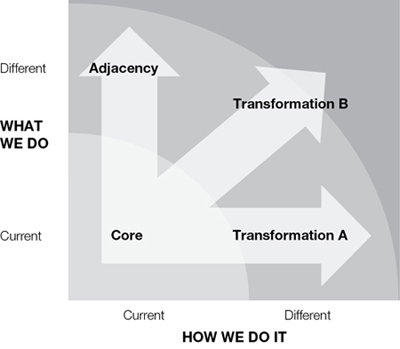

Dual transformation

Figure 1-4 summarizes the core dual transformation equation. It shows how transformation B overlaps with, but is distinct from, transformation A. It also includes the conscious and thoughtful capabilities link between the two transformations. It also, with a couple of doodles, looks somewhat like a butterfly, which is a useful metaphor for dual transformation.

Dual Transformation in the Health Care Industry

An in-process example of dual transformation from the health care industry contrasts the strategies on which this book focuses with other strategies management can use to renew and reinvigorate organizations.

In 1961, medical giant Johnson & Johnson acquired Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a leading Belgian drug company founded by prolific drug maker Paul Janssen. Over the next five decades, Janssen served as an anchor of impressive growth for J&J. As of 2016, pharmaceutical sales contributed more than $30 billion in global revenues, close to half of the healthcare giant’s overall revenues.

The story begins in the late 2000s, when it became clear that Janssen needed to transform. Patent expiration of major drugs had led to declining sales, and Janssen’s development pipeline wasn’t robust enough to close the resulting gap. More broadly, J&J’s pharmaceutical sector comprised a collection of decentralized businesses, built over time through a series of acquisitions and restructurings, leading to duplicative, subscale efforts. So in the first step, the company significantly simplified and streamlined an overly complex organization by centralizing disparate operating units under the Janssen umbrella and focusing the R&D portfolio from projects in thirty-three disease areas to thirteen (it further narrowed this number to eleven over the next few years).

“It started with a change in philosophy,” explained Dr. William N. Hait, Janssen’s global head of R&D. “Our original philosophy was to place many small bets in small R&D organizations working semiautonomously without an overarching strategy, with the belief that what would bubble up would be great ideas leading to great products. The problem was that when we looked at what we could invest in each area compared to competitors, we realized we were spreading our investment dollars much too thin.”

Then, in 2012, Janssen began to change its core drug discovery and development process. The change centered on a commitment to “transformational medical innovation”: emerging science and technology that had the potential to produce radically better health outcomes. Rivals like Pfizer and Novartis were embracing the emergence of generic drugs and biosimilars (similar to off-patent biologically derived drugs), and the industry in general was focused on emerging markets as drivers of growth. Janssen’s bet was that extraordinary advances in life science knowledge and technologies would lead to an acceleration of highly innovative treatments for major medical problems.

Janssen pursued a two-pronged strategy to consistently deliver against this high bar. First, it decided to develop deep expertise in what it called “disease area strongholds.” The idea was to identify diseases that had significant unmet medical need, high potential for innovation, and where Janssen had—or could build—great scientific strength. The company built teams of world-class experts in selected disease areas in order to be on the cutting edge of rapidly emerging science and to accelerate the research and development of drug candidates to patients waiting for solutions.

Then Janssen amplified the disease area strongholds by making perhaps an even more fundamental shift in its R&D paradigm. Rather than focus on compounds invented by internal scientists, Janssen would become world-class at connecting with and amplifying the power of early-stage external scientists wherever those might be in the world. Janssen aspired to be the partner of choice for university researchers and early-stage startups; the idea was to identify attractive compounds early, work with inventors, and then, if it made strategic sense, license or acquire the compound and plug it in to Janssen’s development and distribution machine. The company set up innovation centers in four locations around the world to be embedded in innovative ecosystems and increase access to interesting. It augmented those centers with no-strings-attached biotech incubators that provided fully equipped laboratory space and access to J&J expertise. Incubated startups could end up as standalone businesses, could be acquired by competitors to J&J, or J&J could acquire select startups.

“This required a shift in the culture around ‘not discovered here,’” Hait commented. “We had to accept the fact that others might be ahead of us, or better than us, and we should be open to it. That culture is now deeply ingrained in Janssen. Even the most recalcitrant groups that felt that only J&J science was good have come around. It has been a huge benefit to us. Once we identify the top targets to go after, we don’t care where the drug comes from. It allows us to move very quickly.”

These moves significantly increased early-stage deals and enhanced Janssen’s role and reputation in the innovation community. Pharmaceuticals went from a laggard to the leading sector at J&J, driving the growth of the overall corporation. Janssen became the fastest-growing large pharmaceutical company in the world’s major markets, and the industry leader in R&D productivity for four years in a row between 2013 and 2016.

An example of the transformation comes from Janssen’s successful development of a drug for people suffering from a variety of deadly blood cancers. Janssen’s disease area stronghold experts in hematological malignancies were on the lookout for molecules that inhibited an enzyme called BTK, which is implicated in the development of blood cancers. Researchers found an attractive candidate in ibrutinib, a compound being developed by biotech startup Pharmacyclics. In late 2011 Janssen made an up-front payment of $150 million for the rights to 50 percent of ibrutinib-related sales, and it drove the development process, reaching market with a drug branded Imbruvica in 2013. In 2015 AbbVie bought out Pharmacyclics, along with rights to the remaining 50 percent of Imbruvica sales, for $22 billion.

In 2015, Janssen took the next step in its journey by announcing plans to shift from treating diseases to preventing them. It put forward the provocative notion that it would “intercept” diseases before they manifested. The idea involves leveraging the wealth of health data increasingly available to us—from our genetics and biometrics to our family histories and the signals about our day-to-day behaviors picked up from health-tracking devices and increasingly sophisticated sensors—to stop disease-causing processes in their tracks. Imagine the human equivalent of a Check Engine light that appears automatically on a car dashboard, highlighting the need for some kind of preventive intervention. Further, consider receiving a regimen of customized recommendations for changes in diet, lifestyle, and behavior, along with medicines or other interventions to treat your personal risk for disease, as opposed to the one-size-fits-all health and wellness recommendations we get now. Hait explains.

No one wants to be diagnosed with a disease so they can then get treated. If you’re unfortunate enough to get a disease, you want it to be cured so you don’t have to worry about it anymore. However, today for the most part we develop drugs that manage manifestations of disease. The disruption would be to bring medical solutions that prevent multiple myeloma, for example. With that, all of our business in selling myeloma drugs would be gone, since there would be no myeloma any longer. If that’s where the disruption will come from, and that’s where patients will benefit the most, let’s take a look at what we’d have to do to prevent, intercept, or cure diseases, rather than wait until people are sick to then treat the manifestations of diseases.

Janssen formed an innovation group called the disease interception accelerator (DIA) to shape and speed the most promising research in this area. One of the DIA’s ventures focuses on intercepting type 1 diabetes (T1D), which typically strikes young children and results in a lifetime of dependence on insulin. It turns out that T1D does not start when a child suddenly becomes ill with an attack of diabetic ketoacidosis and must be rushed to the hospital; rather, it is the result of a silent, multiyear, multistage autoimmune attack. Janssen scientists and their partners are working on diagnostics and interventions that target these silent early stages of the disease. The researchers’ intention is to protect the pancreatic beta cells that naturally produce insulin before they’re killed off and need to be artificially supplemented. Janssen’s first drug candidate for this strategy entered clinical trials in 2016 in children with early-stage diabetes.

Janssen is well aware that success will require significant business model innovation. Disease interception solutions are likely to include diagnostics, consumer products, and other interventions that go beyond traditional drugs. And, in many cases, no one product will ensure interception. Rather, consumers will need to integrate a variety of products and services. Finally, it is difficult to prove the financial and societal value of disease prevention and interception, requiring deep partnership with regulators, policy makers, and payers.

To address these challenges, the DIA is working with like-minded stakeholders and exploring new business models and nontraditional partnerships. Clearly, the work to intercept diseases is still in its early stages. Nonetheless, the simultaneous pursuit of two goals—new ways to develop drugs, and a radical reframing of the fundamental problem the organization solves—positions Janssen to drive significant strategic transformation in the years to come.

The What and the How of Dual Transformation

When Janssen first confronted the challenges of commoditization and sagging performance, it had an array of strategic options. Separating the unique roles of transformation A and transformation B requires, first, a clear and consistent definition of today’s business—a seemingly simple step that is easy to skip.

It is easy to describe what a company sells. In the case of Janssen that would be traditional drugs. But as Peter Drucker famously wrote in 1964, “The customer rarely buys what the company thinks it sells him.” Companies think that they provide products or sell solutions, but that’s not what customers perceive. They have a problem, and the company has a solution to the problem. Products and services don’t define a company. Rather, what a company does (or the problem it solves for customers) and how it uniquely solves that problem—these are what define a company.

In previous publications, we’ve called the what the job to be done. The how involves key components of the company’s business model: things, such as brands, physical assets, retail stores, patents, and so on; know-how, such as the ability to work with regulators or knowledge about managing complex networks; and financial components, such as how the company earns revenues, translates revenues into profits, and translates profits into free cash flow. Chapter 2 describes the concepts of jobs to be done and business models in more depth.

Historically, the what Janssen addressed was treating a select number of complicated medical conditions, such as schizophrenia, rheumatoid arthritis, and HIV. Its how, at the beginning of its transformation journey, involved investing heavily in proprietary research laboratories and drug development capabilities that produced innovative medicines to be sold by the company’s skilled salesforce.

Figure 1-5 shows the set of strategic choices leaders have when they choose to fundamentally change a company. It starts in the lower-left quadrant with core optimization.

For J&J, core optimization involved the consolidation of disparate pharmaceutical businesses under the Janssen banner, while streamlining operations and the R&D portfolio. Generally, an organization should constantly be looking for ways to improve its competitive position by improving productivity, innovating to produce better products or services than competitors, or finding new paths to customers that historically have been hard to reach. This is well-covered territory and not a focus of this book. It is worth emphasizing, however, that if you can do what you’re currently doing better, faster, and cheaper, that may be good, is likely necessary, and certainly helps support what follows; but it is not the kind of strategic transformation described in this book. Cost cutting, in particular, might be brutally difficult, but on its own it is not what we mean by the word transformation. If all you are doing is playing yesterday’s game better, your odds of surviving Schumpeter’s creative destruction are low.

Strategic choices for leaders

Janssen’s decision to focus on disease area strongholds and develop the capability to identify and ingest external innovation is transformation A, because it is a new way to solve an old problem—a move along the horizontal axis of figure 1-5. By this action, Janssen is doing the same job it historically did for the end customer—helping manage a select number of medical conditions via pharmaceutical products—but doing it in a fundamentally different way. Disease interception, on the other hand, moves toward the upper-right quadrant, because it solves a new (but related) problem in a new (but related) way. This is transformation B.

One strategy not described in Janssen’s story is a popular one in the industry: growing by acquiring other large pharmaceutical companies to move into new therapeutic areas or new drug modalities (such as biologics). For example, in 2009, when Janssen began to grapple with its strategic challenges, Merck splashed out close to $50 billion to acquire Schering-Plough, and Pfizer paid almost $70 billion to buy Wyeth. These kinds of moves, often called adjacencies, involve using existing capabilities to solve new problems for customers; they are represented by a vertical move toward the upper-left quadrant in figure 1-5.

A classic example of a homegrown adjacency effort is Procter & Gamble’s (P&G) moves in the 1990s and 2000s into new categories like fine fragrances (which it exited in 2015), home-based teeth whitening, and quick housecleaning (through its Swiffer and Febreze brands). In each case P&G expanded to do new jobs for consumers, solving problems it never had solved before. But it was able to follow its time-tested model of distributing consumable products through mass-market retailers like Walmart and Tesco, building proprietary technologies that provided superior benefits compared with competitors’ and investing heavily in advertising.

Well-structured adjacent moves can be powerful ways to grow and increase the resilience of the core business and should be a part of any company’s overall growth strategy. However, because they don’t require changing a company’s fundamental how, again they tend not to change the face or nature of a company and therefore are not a focus of this book.

Leading Dual Transformation

Dual transformation shifts an organization’s center of gravity. If we had to put a number on it, we would say that you have made a dual transformation when B constitutes at least one-third of the total enterprise, with a faster growth rate than A, positioning B to become tomorrow’s core business. It is the hardest challenge a leader will ever face. Part II of this book details four key leadership mindsets you need to succeed.

The courage to choose before the platform burns (chapter 5). Paradoxically, the more obvious the need to transform, the harder it is to do it. Netflix founder, CEO, and chairman Reed Hastings started to change Netflix’s core business years before it was necessary, an action that set his company up for a decade of successful growth. Similarly, in the face of record performance and regulatory changes that seemingly guaranteed years of growth, Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini made the historic decision to dramatically reconfigure the health insurance giant.

The clarity to focus on a select few moonshots (chapter 6). One of the greatest mistakes leaders make is to approach transformation B without a focused strategy. Just as John F. Kennedy urged the United States in 1961 to send a man to the moon and bring him back by the end of the decade, leaders need to identify a handful of high-potential opportunities. We provide a detailed view into the process a leading water utility in the Philippines followed to select two such moonshots in just ninety days.

The curiosity to explore even if the probable outcome is failure (chapter 7). Even though focus is important, leaders must recognize that the specific strategy that will power transformation B will come out of a process of trial and error, with many efforts failing along the way. For example, Singtel is an extremely disciplined telecommunications company, with a strong emphasis on financial discipline. From 2010 to 2015 it successfully branched into new markets and strengthened its culture of innovation by splicing curiosity into its corporate DNA.

The conviction to persevere in the face of predictable crises (chapter 8). There will be dark days—times when a board member doubts, when shareholders question, when even committed executives waver. Leaders must have the conviction to remain firm in the face of crises of commitment, conflict, and identity. A motivating purpose and relentless separation of the work—with leaders repeating the mantra “A does A, B does B”—helps reinforce that conviction.

Chapter 9 concludes by providing snapshots from the dual transformation journey, with insights from a diverse set of leaders reflecting on their own experiences.

The case studies in this book represent a meaningful sample of the instructive examples we have found through our research or have experienced firsthand. Historically, when disruption strikes you could place a simple bet: for the entrant, against the incumbent. Indeed, the afterword describes who’s next—industries facing increasing threats over the next few years. But remember, those threats also present massive opportunities. Companies that successfully execute dual transformation can own the future instead of being disrupted by it.