Day 5. Organizing into Functions

Although object-oriented programming has shifted attention from functions and toward objects, functions nonetheless remain a central component of any program. Global functions can exist outside of objects and classes, and member functions (sometimes called member methods) exist within a class and do its work.

Today, you will learn

• What a function is and what its parts are

• How to declare and define functions

• How to pass parameters into functions

• How to return a value from a function

You’ll start with global functions today, and tomorrow you’ll see how functions work from within classes and objects as well.

What Is a Function?

A function is, in effect, a subprogram that can act on data and return a value. Every C++ program has at least one function, main(). When your program starts, the main() function is called automatically. main() might call other functions, some of which might call still others.

Because these functions are not part of an object, they are called “global”—that is, they can be accessed from anywhere in your program. For today, you will learn about global functions unless it is otherwise noted.

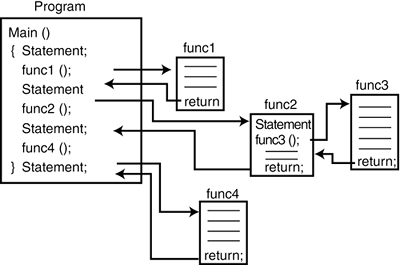

Each function has its own name, and when that name is encountered, the execution of the program branches to the body of that function. This is referred to as calling the function. When the function finishes (through encountering a return statement or the final brace of the function), execution resumes on the next line of the calling function. This flow is illustrated in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1. When a program calls a function, execution switches to the function and then resumes at the line after the function call.

Well-designed functions perform a single, specific, and easily understood task, identified by the function name. Complicated tasks should be broken down into multiple functions, and then each can be called in turn.

Functions come in two varieties: user-defined and built-in. Built-in functions are part of your compiler package—they are supplied by the manufacturer for your use. User-defined functions are the functions you write yourself.

Return Values, Parameters, and Arguments

As you learned on Day 2, “The Anatomy of a C++ Program,” functions can receive values and can return a value.

When you call a function, it can do work and then send back a value as a result of that work. This is called its return value, and the type of that return value must be declared. Thus, if you write

int myFunction();

you are declaring a function called myFunction that will return an integer value. Now consider the following declaration:

int myFunction(int someValue, float someFloat);

This declaration indicates that myFunction will still return an integer, but it will also take two values.

When you send values into a function, these values act as variables that you can manipulate from within the function. The description of the values you send is called a parameter list. In the previous example, the parameter list contains someValue that is a variable of type integer and someFloat that is a variable of type float.

As you can see, a parameter describes the type of the value that will be passed into the function when the function is called. The actual values you pass into the function are called the arguments. Consider the following:

int theValueReturned = myFunction(5,6.7);

Here, you see that an integer variable theValueReturned is initialized with the value returned by myFunction, and that the values 5 and 6.7 are passed in as arguments. The type of the arguments must match the declared parameter types. In this case, the 5 goes to an integer and the 6.7 goes to a float variable, so the values match.

Declaring and Defining Functions

Using functions in your program requires that you first declare the function and that you then define the function. The declaration tells the compiler the name, return type, and parameters of the function. The definition tells the compiler how the function works.

No function can be called from any other function if it hasn’t first been declared. A declaration of a function is called a prototype.

Three ways exist to declare a function:

• Write your prototype into a file, and then use the #include directive to include it in your program.

• Write the prototype into the file in which your function is used.

• Define the function before it is called by any other function. When you do this, the definition acts as its own prototype.

Although you can define the function before using it, and thus avoid the necessity of creating a function prototype, this is not good programming practice for three reasons.

First, it is a bad idea to require that functions appear in a file in a particular order. Doing so makes it hard to maintain the program when requirements change.

Second, it is possible that function A() needs to be able to call function B(), but function B() also needs to be able to call function A() under some circumstances. It is not possible to define function A() before you define function B() and also to define function B() before you define function A(), so at least one of them must be declared in any case.

Third, function prototypes are a good and powerful debugging technique. If your prototype declares that your function takes a particular set of parameters or that it returns a particular type of value, and then your function does not match the prototype, the compiler can flag your error instead of waiting for it to show itself when you run the program. This is like double-entry bookkeeping. The prototype and the definition check each other, reducing the likelihood that a simple typo will lead to a bug in your program.

Despite this, the vast majority of programmers select the third option. This is because of the reduction in the number of lines of code, the simplification of maintenance (changes to the function header also require changes to the prototype), and the order of functions in a file is usually fairly stable. At the same time, prototypes are required in some situations.

Function Prototypes

Many of the built-in functions you use will have their function prototypes already written for you. These appear in the files you include in your program by using #include. For functions you write yourself, you must include the prototype.

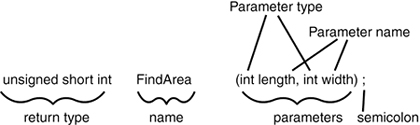

The function prototype is a statement, which means it ends with a semicolon. It consists of the function’s return type and signature. A function signature is its name and parameter list.

The parameter list is a list of all the parameters and their types, separated by commas. Figure 5.2 illustrates the parts of the function prototype.

Figure 5.2. Parts of a function prototype.

The function prototype and the function definition must agree exactly about the return type and signature. If they do not agree, you receive a compile-time error. Note, however, that the function prototype does not need to contain the names of the parameters, just their types. A prototype that looks like this is perfectly legal:

long Area(int, int);

This prototype declares a function named Area() that returns a long and that has two parameters, both integers. Although this is legal, it is not a good idea. Adding parameter names makes your prototype clearer. The same function with named parameters might be

long Area(int length, int width);

It is now much more obvious what this function does and what the parameters are.

Note that all functions have a return type. If none is explicitly stated, the return type defaults to int. Your programs will be easier to understand, however, if you explicitly declare the return type of every function, including main().

If your function does not actually return a value, you declare its return type to be void, as shown here:

void printNumber( int myNumber);

This declares a function called printNumber that has one integer parameter. Because void is used as the return type, nothing is returned.

Defining the Function

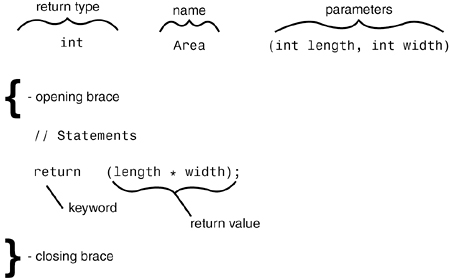

The definition of a function consists of the function header and its body. The header is like the function prototype except that the parameters must be named, and no terminating semicolon is used.

The body of the function is a set of statements enclosed in braces. Figure 5.3 shows the header and body of a function.

Figure 5.3. The header and body of a function.

Listing 5.1 demonstrates a program that includes a function prototype for the Area() function.

Listing 5.1. A Function Prototype and the Definition and Use of That Function

1: // Listing 5.1 - demonstrates the use of function prototypes

2:

3: #include <iostream>

4: int Area(int length, int width); //function prototype

5:

6: int main()

7: {

8: using std::cout;

9: using std::cin;

10:

11: int lengthOfYard;

12: int widthOfYard;

13: int areaOfYard;

14:

15: cout << "

How wide is your yard? ";

16: cin >> widthOfYard;

17: cout << "

How long is your yard? ";

18: cin >> lengthOfYard;

19:

20: areaOfYard= Area(lengthOfYard, widthOfYard);

21:

22: cout << "

Your yard is ";

23: cout << areaOfYard;

24: cout << " square feet

";

25: return 0;

26: }

27:

28: int Area(int len, int wid)

29: {

30: return len * wid;

31: }

![]()

How wide is your yard? 100

How long is your yard? 200

Your yard is 20000 square feet

![]()

The prototype for the Area() function is on line 4. Compare the prototype with the definition of the function on line 28. Note that the name, the return type, and the parameter types are the same. If they were different, a compiler error would have been generated. In fact, the only required difference is that the function prototype ends with a semicolon and has no body.

Also note that the parameter names in the prototype are length and width, but the parameter names in the definition are len and wid. As discussed, the names in the prototype are not used; they are there as information to the programmer. It is good programming practice to match the prototype parameter names to the implementation parameter names, but as this listing shows, this is not required.

The arguments are passed in to the function in the order in which the parameters are declared and defined, but no matching of the names occurs. Had you passed in widthOfYard, followed by lengthOfYard, the FindArea() function would have used the value in widthOfYard for length and lengthOfYard for width.

Note

The body of the function is always enclosed in braces, even when it consists of only one statement, as in this case.

Execution of Functions

When you call a function, execution begins with the first statement after the opening brace ({). Branching can be accomplished by using the if statement. (The if and other related statements will be discussed on Day 7, “More on Program Flow.”) Functions can also call other functions and can even call themselves (see the section “Recursion,” later today).

When a function is done executing, control is returned to the calling function. When the main() function finishes, control is returned to the operating system.

Determining Variable Scope

A variable has scope, which determines how long it is available to your program and where it can be accessed. Variables declared within a block are scoped to that block; they can be accessed only within that block’s braces and “go out of existence” when that block ends. Global variables have global scope and are available anywhere within your program.

Local Variables

Not only can you pass in variables to the function, but you also can declare variables within the body of the function. Variables you declare within the body of the function are called “local” because they exist only locally within the function itself. When the function returns, the local variables are no longer available; they are marked for destruction by the compiler.

Local variables are defined the same as any other variables. The parameters passed in to the function are also considered local variables and can be used exactly as if they had been defined within the body of the function. Listing 5.2 is an example of using parameters and locally defined variables within a function.

Listing 5.2. The Use of Local Variables and Parameters

1: #include <iostream>

2:

3: float Convert(float);

4: int main()

5: {

6: using namespace std;

7:

8: float TempFer;

9: float TempCel;

10:

11: cout << "Please enter the temperature in Fahrenheit: ";

12: cin >> TempFer;

13: TempCel = Convert(TempFer);

14: cout << "

Here’s the temperature in Celsius: ";

15: cout << TempCel << endl;

16: return 0;

17: }

18:

19: float Convert(float TempFer)

20: {

21: float TempCel;

22: TempCel = ((TempFer - 32) * 5) / 9;

23: return TempCel;

24: }

![]()

Please enter the temperature in Fahrenheit: 212

Here’s the temperature in Celsius: 100

Please enter the temperature in Fahrenheit: 32

Here’s the temperature in Celsius: 0

Please enter the temperature in Fahrenheit: 85

Here’s the temperature in Celsius: 29.4444

![]()

On lines 8 and 9, two float variables are declared, one to hold the temperature in Fahrenheit and one to hold the temperature in degrees Celsius. The user is prompted to enter a Fahrenheit temperature on line 11, and that value is passed to the function Convert() on line 13.

With the call of Convert() on line 13, execution jumps to the first line of the Convert() function on line 21, where a local variable, also named TempCel, is declared. Note that this local variable is not the same as the variable TempCel on line 9. This variable exists only within the function Convert(). The value passed as a parameter, TempFer, is also just a local copy of the variable passed in by main().

This function could have named the parameter and local variable anything else and the program would have worked equally well. FerTemp instead of TempFer or CelTemp instead of TempCel would be just as valid and the function would have worked the same. You can enter these different names and recompile the program to see this work.

The local function variable TempCel is assigned the value that results from subtracting 32 from the parameter TempFer, multiplying by 5, and then dividing by 9. This value is then returned as the return value of the function. On line 13, this return value is assigned to the variable TempCel in the main() function. The value is printed on line 15.

The preceding output shows that the program was ran three times. The first time, the value 212 is passed in to ensure that the boiling point of water in degrees Fahrenheit (212) generates the correct answer in degrees Celsius (100). The second test is the freezing point of water. The third test is a random number chosen to generate a fractional result.

Local Variables Within Blocks

You can define variables anywhere within the function, not just at its top. The scope of the variable is the block in which it is defined. Thus, if you define a variable inside a set of braces within the function, that variable is available only within that block. Listing 5.3 illustrates this idea.

Listing 5.3. Variables Scoped Within a Block

1: // Listing 5.3 - demonstrates variables

2: // scoped within a block

3:

4: #include <iostream>

5:

6: void myFunc();

7:

8: int main()

9: {

10: int x = 5;

11: std::cout << "

In main x is: " << x;

12:

13: myFunc();

14:

15: std::cout << "

Back in main, x is: " << x;

16: return 0;

17: }

18:

19: void myFunc()

20: {

21: int x = 8;

22: std::cout << "

In myFunc, local x: " << x << std::endl;

23:

24: {

25: std::cout << "

In block in myFunc, x is: " << x;

26:

27: int x = 9;

28:

29: std::cout << "

Very local x: " << x;

30: }

31:

32: std::cout << "

Out of block, in myFunc, x: " << x << std::endl;

33: }

![]()

In main x is: 5

In myFunc, local x: 8

In block in myFunc, x is: 8

Very local x: 9

Out of block, in myFunc, x: 8

Back in main, x is: 5

![]()

This program begins with the initialization of a local variable, x, on line 10, in main(). The printout on line 11 verifies that x was initialized with the value 5. On line 13, MyFunc() is called.

On line 21 within MyFunc(), a local variable, also named x, is initialized with the value 8. Its value is printed on line 22.

The opening brace on line 24 starts a block. The variable x from the function is printed again on line 25. A new variable also named x, but local to the block, is created on line 27 and initialized with the value 9. The value of this newest variable x is printed on line 29.

The local block ends on line 30, and the variable created on line 27 goes “out of scope” and is no longer visible.

When x is printed on line 32, it is the x that was declared on line 21 within myFunc(). This x was unaffected by the x that was defined on line 27 in the block; its value is still 8.

On line 33, MyFunc() goes out of scope, and its local variable x becomes unavailable. Execution returns to line 14. On line 15, the value of the local variable x, which was created on line 10, is printed. It was unaffected by either of the variables defined in MyFunc().

Needless to say, this program would be far less confusing if these three variables were given unique names!

Parameters Are Local Variables

The arguments passed in to the function are local to the function. Changes made to the arguments do not affect the values in the calling function. This is known as passing by value, which means a local copy of each argument is made in the function. These local copies are treated the same as any other local variables. Listing 5.4 once again illustrates this important point.

Listing 5.4. A Demonstration of Passing by Value

1: // Listing 5.4 - demonstrates passing by value

2: #include <iostream>

3:

4: using namespace std;

5: void swap(int x, int y);

6:

7: int main()

8: {

9: int x = 5, y = 10;

10:

11: cout << "Main. Before swap, x: " << x << " y: " << y << endl;

12: swap(x,y);

13: cout << "Main. After swap, x: " << x << " y: " << y << endl;

14: return 0;

15: }

16:

17: void swap (int x, int y)

18: {

19: int temp;

20:

21: cout << "Swap. Before swap, x: " << x << " y: " << y << endl;

22:

23: temp = x;

24: x = y;

25: y = temp;

26:

27: cout << "Swap. After swap, x: " << x << " y: " << y << endl;

28: }

![]()

Main. Before swap, x: 5 y: 10

Swap. Before swap, x: 5 y: 10

Swap. After swap, x: 10 y: 5

Main. After swap, x: 5 y: 10

![]()

This program initializes two variables in main() and then passes them to the swap() function, which appears to swap them. When they are examined again in main(), however, they are unchanged!

The variables are initialized on line 9, and their values are displayed on line 11. The swap() function is called on line 12, and the variables are passed in.

Execution of the program switches to the swap() function, where on line 21 the values are printed again. They are in the same order as they were in main(), as expected. On lines 23 to 25, the values are swapped, and this action is confirmed by the printout on line 27. Indeed, while in the swap() function, the values are swapped.

Execution then returns to line 13, back in main(), where the values are no longer swapped.

As you’ve figured out, the values passed in to the swap() function are passed by value, meaning that copies of the values are made that are local to swap(). These local variables are swapped on lines 23 to 25, but the variables back in main() are unaffected.

On Day 8, “Understanding Pointers,” and Day 10, “Working with Advanced Functions,” you’ll see alternatives to passing by value that will allow the values in main() to be changed.

Global Variables

Variables defined outside of any function have global scope, and thus are available from any function in the program, including main().

Local variables with the same name as global variables do not change the global variables. A local variable with the same name as a global variable hides the global variable, however. If a function has a variable with the same name as a global variable, the name refers to the local variable—not the global—when used within the function. Listing 5.5 illustrates these points.

Listing 5.5. Demonstrating Global and Local Variables

1: #include <iostream>

2: void myFunction(); // prototype

3:

4: int x = 5, y = 7; // global variables

5: int main()

6: {

7: using namespacestd;

8:

9: cout << "x from main: " << x << endl;

10: cout << "y from main: " << y << endl << endl;

11: myFunction();

12: cout << "Back from myFunction!" << endl << endl;

13: cout << "x from main: " << x << endl;

14: cout << "y from main: " << y << endl;

15: return 0;

16: }

17:

18: void myFunction()

19: {

20: using std::cout;

21: using std:endl;

22: int y = 10;

23:

24: cout << "x from myFunction: " << x << endl;

25: cout << "y from myFunction: " << y << endl << endl;

26: }

![]()

x from main: 5

y from main: 7

x from myFunction: 5

y from myFunction: 10

Back from myFunction!

x from main: 5

y from main: 7

![]()

This simple program illustrates a few key, and potentially confusing, points about local and global variables. On line 4, two global variables, x and y, are declared. The global variable x is initialized with the value 5, and the global variable y is initialized with the value 7.

On lines 9 and 10 in the function main(), these values are printed to the console. Note that the function main() defines neither variable; because they are global, they are already available to main().

When myFunction() is called on line 11, program execution passes to line 18, and on line 22 a local variable, y, is defined and initialized with the value 10. On line 24, myFunction() prints the value of the variable x, and the global variable x is used, just as it was in main(). On line 25, however, when the variable name y is used, the local variable y is used, hiding the global variable with the same name.

The function call ends, and control returns to main(), which again prints the values in the global variables. Note that the global variable y was totally unaffected by the value assigned to myFunction()’s local y variable.

Global Variables: A Word of Caution

In C++, global variables are legal, but they are almost never used. C++ grew out of C, and in C global variables are a dangerous but necessary tool. They are necessary because at times the programmer needs to make data available to many functions, and it is cumbersome to pass that data as a parameter from function to function, especially when many of the functions in the calling sequence only receive the parameter to pass it on to other functions.

Globals are dangerous because they are shared data, and one function can change a global variable in a way that is invisible to another function. This can and does create bugs that are very difficult to find.

On Day 15, “Special Classes and Functions,” you’ll see a powerful alternative to global variables called static member variables.

Considerations for Creating Function Statements

Virtually no limit exists to the number or types of statements that can be placed in the body of a function. Although you can’t define another function from within a function, you can call a function, and of course, main() does just that in nearly every C++ program. Functions can even call themselves, which is discussed soon in the section on recursion.

Although no limit exists to the size of a function in C++, well-designed functions tend to be small. Many programmers advise keeping your functions short enough to fit on a single screen so that you can see the entire function at one time. This is a rule of thumb, often broken by very good programmers, but it is true that a smaller function is easier to understand and maintain.

Each function should carry out a single, easily understood task. If your functions start getting large, look for places where you can divide them into component tasks.

More About Function Arguments

Any valid C++ expression can be a function argument, including constants, mathematical and logical expressions, and other functions that return a value. The important thing is that the result of the expression match the argument type that is expected by the function.

It is even valid for a function to be passed as an argument. After all, the function will evaluate to its return type. Using a function as an argument, however, can make for code that is hard to read and hard to debug.

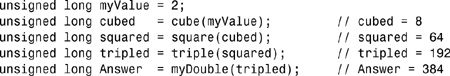

As an example, suppose you have the functions myDouble(), triple(), square(), and cube(), each of which returns a value. You could write

Answer = (myDouble(triple(square(cube(myValue)))));

You can look at this statement in two ways. First, you can see that the function myDouble() takes the function triple() as an argument. In turn, triple() takes the function square(), which takes the function cube() as its argument. The cube() function takes the variable, myValue, as its argument.

Looking at this from the other direction, you can see that this statement takes a variable, myValue, and passes it as an argument to the function cube(), whose return value is passed as an argument to the function square(), whose return value is in turn passed to triple(), and that return value is passed to myDouble(). The return value of this doubled, tripled, squared, and cubed number is now assigned to Answer.

It is difficult to be certain what this code does (was the value tripled before or after it was squared?), and if the answer is wrong, it will be hard to figure out which function failed.

An alternative is to assign each step to its own intermediate variable:

Now, each intermediate result can be examined, and the order of execution is explicit.

Caution

C++ makes it really easy to write compact code like the preceding example used to combine the cube(), square(), triple(), and myDouble() functions. Just because you can make compact code does not mean you should. It is better to make your code easier to read, and thus more maintainable, than to make it as compact as you can.

More About Return Values

Functions return a value or return void. Void is a signal to the compiler that no value will be returned.

To return a value from a function, write the keyword return followed by the value you want to return. The value might itself be an expression that returns a value. For example:

return 5;

return (x > 5);

return (MyFunction());

These are all legal return statements, assuming that the function MyFunction() itself returns a value. The value in the second statement, return (x > 5), will be false if x is not greater than 5, or it will be true. What is returned is the value of the expression, false or true, not the value of x.

When the return keyword is encountered, the expression following return is returned as the value of the function. Program execution returns immediately to the calling function, and any statements following the return are not executed.

It is legal to have more than one return statement in a single function. Listing 5.6 illustrates this idea.

Listing 5.6. A Demonstration of Multiple Return Statements

1: // Listing 5.6 - demonstrates multiple return

2: // statements

3: #include <iostream>

4:

5: int Doubler(int AmountToDouble);

6:

7: int main()

8: {

9: using std::cout;

10:

11: int result = 0;

12: int input;

13:

14: cout << "Enter a number between 0 and 10,000 to double: ";

15: std::cin >> input;

16:

17: cout << "

Before doubler is called... ";

18: cout << "

input: " << input << " doubled: " << result << "

";

19:

20: result = Doubler(input);

21:

22: cout << "

Back from Doubler...

";

23: cout << "

input: " << input << " doubled: " << result << "

";

24:

25: return 0;

26: }

27:

28: int Doubler(int original)

29: {

30: if (original <= 10000)

31: return original * 2;

32: else

33: return -1;

34: std::cout << "You can’t get here!

";

35: }

![]()

Enter a number between 0 and 10,000 to double: 9000

Before doubler is called...

input: 9000 doubled: 0

Back from doubler...

input: 9000 doubled: 18000

Enter a number between 0 and 10,000 to double: 11000

Before doubler is called...

input: 11000 doubled: 0

Back from doubler...

input: 11000 doubled: -1

![]()

A number is requested on lines 14 and 15 and printed on lines 17 and 18, along with the local variable result. The function Doubler() is called on line 20, and the input value is passed as a parameter. The result will be assigned to the local variable, result, and the values will be reprinted on line 23.

On line 30, in the function Doubler(), the parameter is tested to see whether it is less than or equal to 10,000. If it is, then the function returns twice the original number. If the value of original is greater than 10,000, the function returns –1 as an error value.

The statement on line 34 is never reached because regardless of whether the value is less than or equal to 10,000 or greater than 10,000, the function returns on either line 31 or line 33—before it gets to line 34. A good compiler warns that this statement cannot be executed, and a good programmer takes it out!

Default Parameters

For every parameter you declare in a function prototype and definition, the calling function must pass in a value. The value passed in must be of the declared type. Thus, if you have a function declared as

long myFunction(int);

the function must, in fact, take an integer variable. If the function definition differs, or if you fail to pass in an integer, you receive a compiler error.

The one exception to this rule is if the function prototype declares a default value for the parameter. A default value is a value to use if none is supplied. The preceding declaration could be rewritten as

long myFunction (int x = 50);

This prototype says, “myFunction() returns a long and takes an integer parameter. If an argument is not supplied, use the default value of 50.” Because parameter names are not required in function prototypes, this declaration could have been written as

long myFunction (int = 50);

The function definition is not changed by declaring a default parameter. The function definition header for this function would be

long myFunction (int x)

If the calling function did not include a parameter, the compiler would fill x with the default value of 50. The name of the default parameter in the prototype need not be the same as the name in the function header; the default value is assigned by position, not name.

Any or all of the function’s parameters can be assigned default values. The one restriction is this: If any of the parameters does not have a default value, no previous parameter can have a default value.

If the function prototype looks like

long myFunction (int Param1, int Param2, int Param3);

you can assign a default value to Param2 only if you have assigned a default value to Param3. You can assign a default value to Param1 only if you’ve assigned default values to both Param2 and Param3. Listing 5.7 demonstrates the use of default values.

Listing 5.7. A Demonstration of Default Parameter Values

1: // Listing 5.7 - demonstrates use

2: // of default parameter values

3: #include <iostream>

4:

5: int AreaCube(int length, int width = 25, int height = 1);

6:

7: int main()

8: {

9: int length = 100;

10: int width = 50;

11: int height = 2;

12: int area;

13:

14: area = AreaCube(length, width, height);

15: std::cout << "First area equals: " << area << "

";

16:

17: area = AreaCube(length, width);

18: std::cout << "Second time area equals: " << area << "

";

19:

20: area = AreaCube(length);

21: std::cout << "Third time area equals: " << area << "

";

22: return 0;

23: }

24:

25: AreaCube(int length, int width, int height)

26: {

27:

28: return (length * width * height);

29:}

![]()

First area equals: 10000

Second time area equals: 5000

Third time area equals: 2500

![]()

On line 5, the AreaCube() prototype specifies that the AreaCube() function takes three integer parameters. The last two have default values.

This function computes the area of the cube whose dimensions are passed in. If no width is passed in, a width of 25 is used and a height of 1 is used. If the width but not the height is passed in, a height of 1 is used. It is not possible to pass in the height without passing in a width.

On lines 9–11, the dimension’s length, height, and width are initialized, and they are passed to the AreaCube() function on line 14. The values are computed, and the result is printed on line 15.

Execution continues to line 17, where AreaCube() is called again, but with no value for height. The default value is used, and again the dimensions are computed and printed.

Execution then continues to line 20, and this time neither the width nor the height is passed in. With this call to AreaCube(), execution branches for a third time to line 25. The default values are used and the area is computed. Control returns to the main() function where the final value is then printed.

Overloading Functions

C++ enables you to create more than one function with the same name. This is called function overloading. The functions must differ in their parameter list with a different type of parameter, a different number of parameters, or both. Here’s an example:

int myFunction (int, int);

int myFunction (long, long);

int myFunction (long);

myFunction() is overloaded with three parameter lists. The first and second versions differ in the types of the parameters, and the third differs in the number of parameters.

The return types can be the same or different on overloaded functions.

Two functions with the same name and parameter list, but different return types, generate a compiler error. To change the return type, you must also change the signature (name and/or parameter list).

Function overloading is also called function polymorphism. Poly means many, and morph means form: A polymorphic function is many-formed.

Function polymorphism refers to the capability to “overload” a function with more than one meaning. By changing the number or type of the parameters, you can give two or more functions the same function name, and the right one will be called automatically by matching the parameters used. This enables you to create a function that can average integers, doubles, and other values without having to create individual names for each function, such as AverageInts(), AverageDoubles(), and so on.

Suppose you write a function that doubles whatever input you give it. You would like to be able to pass in an int, a long, a float, or a double. Without function overloading, you would have to create four function names:

int DoubleInt(int);

long DoubleLong(long);

float DoubleFloat(float);

double DoubleDouble(double);

With function overloading, you make this declaration:

int Double(int);

long Double(long);

float Double(float);

double Double(double);

This is easier to read and easier to use. You don’t have to worry about which one to call; you just pass in a variable, and the right function is called automatically. Listing 5.8 illustrates the use of function overloading.

Listing 5.8. A Demonstration of Function Polymorphism

1: // Listing 5.8 - demonstrates

2: // function polymorphism

3: #include <iostream>

4:

5: int Double(int);

6: long Double(long);

7: float Double(float);

8: double Double(double);

9:

10: using namespace std;

11:

12: int main()

13: {

14: int myInt = 6500;

15: long myLong = 65000;

16: float myFloat = 6.5F;

17: double myDouble = 6.5e20;

18:

19: int doubledInt;

20: long doubledLong;

21: float doubledFloat;

22: double doubledDouble;

23:

24: cout << "myInt: " << myInt << "

";

25: cout << "myLong: " << myLong << "

";

26: cout << "myFloat: " << myFloat << "

";

27: cout << "myDouble: " << myDouble << "

";

28:

29: doubledInt = Double(myInt);

30: doubledLong = Double(myLong);

31: doubledFloat = Double(myFloat);

32: doubledDouble = Double(myDouble);

33:

34: cout << "doubledInt: " << doubledInt << "

";

35: cout << "doubledLong: " << doubledLong << "

";

36: cout << "doubledFloat: " << doubledFloat << "

";

37: cout << "doubledDouble: " << doubledDouble << "

";

38:

39: return 0;

40: }

41:

42: int Double(int original)

43: {

44: cout << "In Double(int)

";

45: return 2 * original;

46: }

47:

48: long Double(long original)

49: {

50: cout << "In Double(long)

";

51: return 2 * original;

52: }

53:

54: float Double(float original)

55: {

56: cout << "In Double(float)

";

57: return 2 * original;

58: }

59:

60: double Double(double original)

61: {

62: cout << "In Double(double)

";

63: return 2 * original;

64: }

![]()

myInt: 6500

myLong: 65000

myFloat: 6.5

myDouble: 6.5e+20

In Double(int)

In Double(long)

In Double(float)

In Double(double)

DoubledInt: 13000

DoubledLong: 130000

DoubledFloat: 13

DoubledDouble: 1.3e+21

![]()

The Double() function is overloaded with int, long, float, and double. The prototypes are on lines 5–8, and the definitions are on lines 42–64.

Note that in this example, the statement using namespace std; has been added on line 10, outside of any particular function. This makes the statement global to this file, and thus the namespace is used in all the functions declared within this file.

In the body of the main program, eight local variables are declared. On lines 14–17, four of the values are initialized, and on lines 29–32, the other four are assigned the results of passing the first four to the Double() function. Note that when Double() is called, the calling function does not distinguish which one to call; it just passes in an argument, and the correct one is invoked.

The compiler examines the arguments and chooses which of the four Double() functions to call. The output reveals that each of the four was called in turn, as you would expect.

Special Topics About Functions

Because functions are so central to programming, a few special topics arise that might be of interest when you confront unusual problems. Used wisely, inline functions can help you squeak out that last bit of performance. Function recursion is one of those wonderful, esoteric bits of programming, which, every once in a while, can cut through a thorny problem otherwise not easily solved.

Inline Functions

When you define a function, normally the compiler creates just one set of instructions in memory. When you call the function, execution of the program jumps to those instructions, and when the function returns, execution jumps back to the next line in the calling function. If you call the function 10 times, your program jumps to the same set of instructions each time. This means only one copy of the function exists, not 10.

A small performance overhead occurs in jumping in and out of functions. It turns out that some functions are very small, just a line or two of code, and an efficiency might be gained if the program can avoid making these jumps just to execute one or two instructions. When programmers speak of efficiency, they usually mean speed; the program runs faster if the function call can be avoided.

If a function is declared with the keyword inline, the compiler does not create a real function; it copies the code from the inline function directly into the calling function. No jump is made; it is just as if you had written the statements of the function right into the calling function.

Note that inline functions can bring a heavy cost. If the function is called 10 times, the inline code is copied into the calling functions each of those 10 times. The tiny improvement in speed you might achieve might be more than swamped by the increase in size of the executable program, which might in fact actually slow the program!

The reality is that today’s optimizing compilers can almost certainly do a better job of making this decision than you can; and so it is generally a good idea not to declare a function inline unless it is only one or at most two statements in length. When in doubt, though, leave inline out.

Note

Performance optimization is a difficult challenge, and most programmers are not good at identifying the location of performance problems in their programs without help. Help, in this case, involves specialized programs like debuggers and profilers.

Also, it is always better to write code that is clear and understandable than to write code that contains your guess about what will run fast or slow, but is harder to understand. This is because it is easier to make understandable code run faster.

Listing 5.9 demonstrates an inline function.

Listing 5.9. A Demonstration of an Inline Function

1: // Listing 5.9 - demonstrates inline functions

2: #include <iostream>

3:

4: inline int Double(int);

5:

6: int main()

7: {

8: int target;

9: using std::cout;

10: using std::cin;

11: using std::endl;

12:

13: cout << "Enter a number to work with: ";

14: cin >> target;

15: cout << "

";

16:

17: target = Double(target);

18: cout << "Target: " << target << endl;

19:

20: target = Double(target);

21: cout << "Target: " << target << endl;

22:

23: target = Double(target);

24: cout << "Target: " << target << endl;

25: return 0;

26: }

27:

28: int Double(int target)

29: {

30: return 2*target;

31: }

![]()

Enter a number to work with: 20

Target: 40

Target: 80

Target: 160

![]()

On line 4, Double() is declared to be an inline function taking an int parameter and returning an int. The declaration is just like any other prototype except that the keyword inline is prepended just before the return value.

This compiles into code that is the same as if you had written the following:

target = 2 * target;

everywhere you entered

target = Double(target);

By the time your program executes, the instructions are already in place, compiled into the .obj file. This saves a jump and return in the execution of the code at the cost of a larger program.

Note

The inline keyword is a hint to the compiler that you want the function to be inlined. The compiler is free to ignore the hint and make a real function call.

Recursion

A function can call itself. This is called recursion, and recursion can be direct or indirect. It is direct when a function calls itself; it is indirect recursion when a function calls another function that then calls the first function.

Some problems are most easily solved by recursion, usually those in which you act on data and then act in the same way on the result. Both types of recursion, direct and indirect, come in two varieties: those that eventually end and produce an answer, and those that never end and produce a runtime failure. Programmers think that the latter is quite funny (when it happens to someone else).

It is important to note that when a function calls itself, a new copy of that function is run. The local variables in the second version are independent of the local variables in the first, and they cannot affect one another directly, any more than the local variables in main() can affect the local variables in any function it calls, as was illustrated in Listing 5.3.

To illustrate solving a problem using recursion, consider the Fibonacci series:

1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,34…

Each number, after the second, is the sum of the two numbers before it. A Fibonacci problem might be to determine what the 12th number in the series is.

To solve this problem, you must examine the series carefully. The first two numbers are 1. Each subsequent number is the sum of the previous two numbers. Thus, the seventh number is the sum of the sixth and fifth numbers. More generally, the nth number is the sum of n–2 and n–1, as long as n > 2.

Recursive functions need a stop condition. Something must happen to cause the program to stop recursing, or it will never end. In the Fibonacci series, n < 3 is a stop condition (that is, when n is less than 3 the program can stop working on the problem).

An algorithm is a set of steps you follow to solve a problem. One algorithm for the Fibonacci series is the following:

1. Ask the user for a position in the series.

2. Call the fib() function with that position, passing in the value the user entered.

3. The fib() function examines the argument (n). If n < 3 it returns 1; otherwise, fib() calls itself (recursively) passing in n-2. It then calls itself again passing in n-1, and returns the sum of the first call and the second.

If you call fib(1), it returns 1. If you call fib(2), it returns 1. If you call fib(3), it returns the sum of calling fib(2) and fib(1). Because fib(2) returns 1 and fib(1) returns 1, fib(3) returns 2 (the sum of 1 + 1).

If you call fib(4), it returns the sum of calling fib(3) and fib(2). You just saw that fib(3) returns 2 (by calling fib(2) and fib(1)) and that fib(2) returns 1, so fib(4) sums these numbers and returns 3, which is the fourth number in the series.

Taking this one more step, if you call fib(5), it returns the sum of fib(4) and fib(3). You’ve seen that fib(4) returns 3 and fib(3) returns 2, so the sum returned is 5.

This method is not the most efficient way to solve this problem (in fib(20) the fib() function is called 13,529 times!), but it does work. Be careful—if you feed in too large a number, you’ll run out of memory. Every time fib() is called, memory is set aside. When it returns, memory is freed. With recursion, memory continues to be set aside before it is freed, and this system can eat memory very quickly. Listing 5.10 implements the fib() function.

Caution

When you run Listing 5.10, use a small number (less than 15). Because this uses recursion, it can consume a lot of memory.

Listing 5.10. A Demonstration of Recursion Using the Fibonacci Series

1: // Fibonacci series using recursion

2: #include <iostream>

3: int fib (int n);

4:

5: int main()

6: {

7:

8: int n, answer;

9: std::cout << "Enter number to find: ";

10: std::cin >> n;

11:

12: std::cout << "

";

13:

14: answer = fib(n);

15:

16: std::cout << answer << " is the " << n;

17: std::cout << "th Fibonacci number

";

18: return 0;

19: }

20:

21: int fib (int n)

22: {

23: std::cout << "Processing fib(" << n << ")... ";

24:

25: if (n < 3 )

26: {

27: std::cout << "Return 1!

";

28: return (1);

29: }

30: else

31: {

32: std::cout << "Call fib(" << n-2 << ") ";

33: std::cout << "and fib(" << n-1 << ").

";

34: return( fib(n-2) + fib(n-1));

35: }

36: }

![]()

Enter number to find: 6

Processing fib(6)... Call fib(4) and fib(5).

Processing fib(4)... Call fib(2) and fib(3).

Processing fib(2)... Return 1!

Processing fib(3)... Call fib(1) and fib(2).

Processing fib(1)... Return 1!

Processing fib(2)... Return 1!

Processing fib(5)... Call fib(3) and fib(4).

Processing fib(3)... Call fib(1) and fib(2).

Processing fib(1)... Return 1!

Processing fib(2)... Return 1!

Processing fib(4)... Call fib(2) and fib(3).

Processing fib(2)... Return 1!

Processing fib(3)... Call fib(1) and fib(2).

Processing fib(1)... Return 1!

Processing fib(2)... Return 1!

8 is the 6th Fibonacci number

Some compilers have difficulty with the use of operators in a cout statement. If you receive a warning on line 32, place parentheses around the subtraction operation so that lines 32 and 33 become:

std::cout << "Call fib(" << (n-2) << ") "; std::cout << "and fib(" << (n-1) << "). ";

![]()

The program asks for a number to find on line 9 and assigns that number to n. It then calls fib() with n. Execution branches to the fib() function, where, on line 23, it prints its argument.

The argument n is tested to see whether it is less than 3 on line 25; if so, fib() returns the value 1. Otherwise, it returns the sum of the values returned by calling fib() on n-2 and n-1.

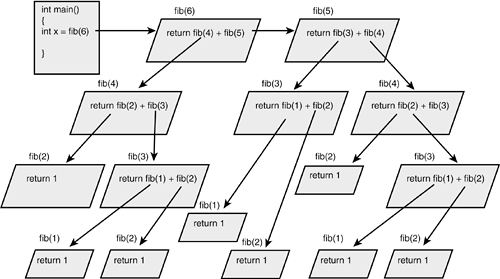

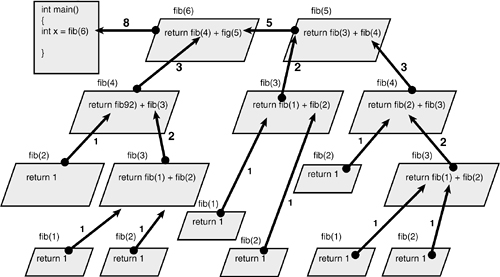

It cannot return these values until the call (to fib()) is resolved. Thus, you can picture the program diving into fib repeatedly until it hits a call to fib that returns a value. The only calls that return a value are the calls to fib(2) and fib(1). These values are then passed up to the waiting callers, which, in turn, add the return value to their own, and then they return. Figures 5.4 and 5.5 illustrate this recursion into fib().

Figure 5.4. Using recursion.

Figure 5.5. Returning from recursion.

In the example, n is 6 so fib(6) is called from main(). Execution jumps to the fib() function, and n is tested for a value less than 3 on line 25. The test fails, so fib(6) returns on line 34 the sum of the values returned by fib(4) and fib(5). Look at line 34:

return( fib(n-2) + fib(n-1));

From this return statement a call is made to fib(4) (because n == 6, fib(n-2) is the same as fib(4)) and another call is made to fib(5) (fib(n-1)), and then the function you are in (fib(6)) waits until these calls return a value. When these return a value, this function can return the result of summing those two values.

Because fib(5) passes in an argument that is not less than 3, fib() is called again, this time with 4 and 3. fib(4) in turn calls fib(3) and fib(2).

The output traces these calls and the return values. Compile, link, and run this program, entering first 1, then 2, then 3, building up to 6, and watch the output carefully.

This would be a great time to start experimenting with your debugger. Put a break point on line 21 and then trace into each call to fib, keeping track of the value of n as you work your way into each recursive call to fib.

Recursion is not used often in C++ programming, but it can be a powerful and elegant tool for certain needs.

Recursion is a tricky part of advanced programming. It is presented here because it can be useful to understand the fundamentals of how it works, but don’t worry too much if you don’t fully understand all the details.

How Functions Work—A Peek Under the Hood

When you call a function, the code branches to the called function, parameters are passed in, and the body of the function is executed. When the function completes, a value is returned (unless the function returns void), and control returns to the calling function.

How is this task accomplished? How does the code know where to branch? Where are the variables kept when they are passed in? What happens to variables that are declared in the body of the function? How is the return value passed back out? How does the code know where to resume?

Most introductory books don’t try to answer these questions, but without understanding this information, you’ll find that programming remains a fuzzy mystery. The explanation requires a brief tangent into a discussion of computer memory.

Levels of Abstraction

One of the principal hurdles for new programmers is grappling with the many layers of intellectual abstraction. Computers, of course, are only electronic machines. They don’t know about windows and menus, they don’t know about programs or instructions, and they don’t even know about ones and zeros. All that is really going on is that voltage is being measured at various places on an integrated circuit. Even this is an abstraction: Electricity itself is just an intellectual concept representing the behavior of subatomic particles, which arguably are themselves intellectual abstractions(!).

Few programmers bother with any level of detail below the idea of values in RAM. After all, you don’t need to understand particle physics to drive a car, make toast, or hit a baseball, and you don’t need to understand the electronics of a computer to program one.

You do need to understand how memory is organized, however. Without a reasonably strong mental picture of where your variables are when they are created and how values are passed among functions, it will all remain an unmanageable mystery.

Partitioning RAM

When you begin your program, your operating system (such as DOS, Linux/Unix, or Microsoft Windows) sets up various areas of memory based on the requirements of your compiler. As a C++ programmer, you’ll often be concerned with the global namespace, the free store, the registers, the code space, and the stack.

Global variables are in global namespace. You’ll learn more about global namespace and the free store in coming days, but here, the focus is on the registers, code space, and stack.

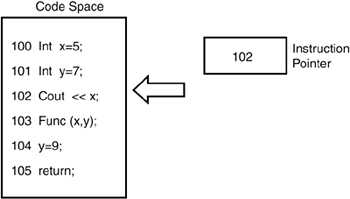

Registers are a special area of memory built right into the central processing unit (or CPU). They take care of internal housekeeping. A lot of what goes on in the registers is beyond the scope of this book, but what you should be concerned with is the set of registers responsible for pointing, at any given moment, to the next line of code. These registers, together, can be called the instruction pointer. It is the job of the instruction pointer to keep track of which line of code is to be executed next.

The code itself is in the code space, which is that part of memory set aside to hold the binary form of the instructions you created in your program. Each line of source code is translated into a series of instructions, and each of these instructions is at a particular address in memory. The instruction pointer has the address of the next instruction to execute. Figure 5.6 illustrates this idea.

Figure 5.6. The instruction pointer.

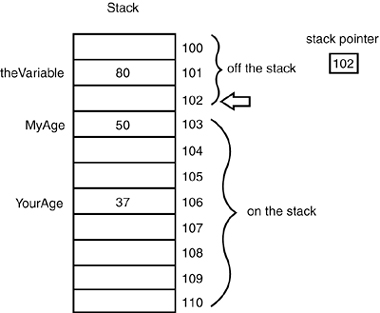

The stack is a special area of memory allocated for your program to hold the data required by each of the functions in your program. It is called a stack because it is a last-in, first-out queue, much like a stack of dishes at a cafeteria, as shown in Figure 5.7.

Figure 5.7. A stack.

Last-in, first-out means that whatever is added to the stack last is the first thing taken off. This differs from most queues in which the first in is the first out (like a line at a theater: The first one in line is the first one off). A stack is more like a stack of coins: If you stack 10 pennies on a tabletop and then take some back, the last three you put on top are the first three you take off.

When data is pushed onto the stack, the stack grows; as data is popped off the stack, the stack shrinks. It isn’t possible to pop a dish off the stack without first popping off all the dishes placed on after that dish.

A stack of dishes is the common analogy. It is fine as far as it goes, but it is wrong in a fundamental way. A more accurate mental picture is of a series of cubbyholes aligned top to bottom. The top of the stack is whatever cubby the stack pointer (which is another register) happens to be pointing to.

Each of the cubbies has a sequential address, and one of those addresses is kept in the stack pointer register. Everything below that magic address, known as the top of the stack, is considered to be on the stack. Everything above the top of the stack is considered to be off the stack and invalid. Figure 5.8 illustrates this idea.

Figure 5.8. The stack pointer.

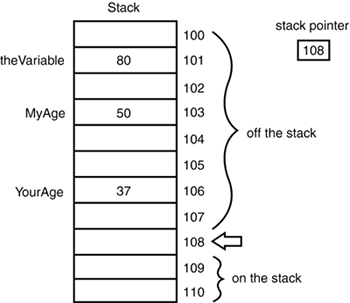

When data is put on the stack, it is placed into a cubby above the stack pointer, and then the stack pointer is moved to the new data. When data is popped off the stack, all that really happens is that the address of the stack pointer is changed by moving it down the stack. Figure 5.9 makes this rule clear.

Figure 5.9. Moving the stack pointer.

The data above the stack pointer (off the stack) might or might not be changed at any time. These values are referred to as “garbage” because their value is no longer reliable.

The Stack and Functions

The following is an approximation of what happens when your program branches to a function. (The details will differ depending on the operating system and compiler.)

1. The address in the instruction pointer is incremented to the next instruction past the function call. That address is then placed on the stack, and it will be the return address when the function returns.

2. Room is made on the stack for the return type you’ve declared. On a system with two-byte integers, if the return type is declared to be int, another two bytes are added to the stack, but no value is placed in these bytes (that means that whatever “garbage” was in those two bytes remains until the local variable is initialized).

3. The address of the called function, which is kept in a special area of memory set aside for that purpose, is loaded into the instruction pointer, so the next instruction executed will be in the called function.

4. The current top of the stack is now noted and is held in a special pointer called the stack frame. Everything added to the stack from now until the function returns will be considered “local” to the function.

5. All the arguments to the function are placed on the stack.

6. The instruction now in the instruction pointer is executed, thus executing the first instruction in the function.

7. Local variables are pushed onto the stack as they are defined.

When the function is ready to return, the return value is placed in the area of the stack reserved at step 2. The stack is then popped all the way up to the stack frame pointer, which effectively throws away all the local variables and the arguments to the function.

The return value is popped off the stack and assigned as the value of the function call itself, and the address stashed away in step 1 is retrieved and put into the instruction pointer. The program thus resumes immediately after the function call, with the value of the function retrieved.

Some of the details of this process change from compiler to compiler, or between computer operating system or processors, but the essential ideas are consistent across environments. In general, when you call a function, the return address and the parameters are put on the stack. During the life of the function, local variables are added to the stack. When the function returns, these are all removed by popping the stack.

In coming days, you will learn about other places in memory that are used to hold data that must persist beyond the life of the function.

Summary

Today’s lesson introduced functions. A function is, in effect, a subprogram into which you can pass parameters and from which you can return a value. Every C++ program starts in the main() function, and main(), in turn, can call other functions.

A function is declared with a function prototype, which describes the return value, the function name, and its parameter types. A function can optionally be declared inline. A function prototype can also declare default values for one or more of the parameters.

The function definition must match the function prototype in return type, name, and parameter list. Function names can be overloaded by changing the number or type of parameters; the compiler finds the right function based on the argument list.

Local function variables, and the arguments passed in to the function, are local to the block in which they are declared. Parameters passed by value are copies and cannot affect the value of variables in the calling function.

Q&A

Q Why not make all variables global?

A At one time, this was exactly how programming was done. As programs became more complex, however, it became very difficult to find bugs in programs because data could be corrupted by any of the functions—global data can be changed anywhere in the program. Years of experience have convinced programmers that data should be kept as local as possible, and access to changing that data should be narrowly defined.

Q When should the keyword inline be used in a function prototype?

A If the function is very small, no more than a line or two, and won’t be called from many places in your program, it is a candidate for inlining.

Q Why aren’t changes to the value of function arguments reflected in the calling function?

A Arguments passed to a function are passed by value. That means that the argument in the function is actually a copy of the original value. This concept is explained in depth in the section “How Functions Work—A Peek Under the Hood.”

Q If arguments are passed by value, what do I do if I need to reflect the changes back in the calling function?

A On Day 8, pointers will be discussed and on Day 9, you’ll learn about references. Use of pointers or references will solve this problem, as well as provide a way around the limitation of returning only a single value from a function.

Q What happens if I have the following two functions?

int Area (int width, int length = 1); int Area (int size);

Will these overload? A different number of parameters exist, but the first one has a default value.

A The declarations will compile, but if you invoke Area with one parameter, you will receive an error: ambiguity between Area(int, int) and Area(int).

Workshop

The Workshop provides quiz questions to help you solidify your understanding of the material covered and exercises to provide you with experience in using what you’ve learned. Try to answer the quiz and exercise questions before checking the answers in Appendix D, and be certain that you understand the answers before continuing to tomorrow’s lesson.

Quiz

1. What are the differences between the function prototype and the function definition?

2. Do the names of parameters have to agree in the prototype, definition, and call to the function?

3. If a function doesn’t return a value, how do you declare the function?

4. If you don’t declare a return value, what type of return value is assumed?

5. What is a local variable?

6. What is scope?

7. What is recursion?

8. When should you use global variables?

9. What is function overloading?

Exercises

1. Write the prototype for a function named Perimeter(), which returns an unsigned long int and takes two parameters, both unsigned short ints.

2. Write the definition of the function Perimeter() as described in Exercise 1. The two parameters represent the length and width of a rectangle. Have the function return the perimeter (twice the length plus twice the width).

3. BUG BUSTERS: What is wrong with the function in the following code?

#include <iostream>

void myFunc(unsigned short int x);

int main()

{

unsigned short int x, y;

y = myFunc(int);

std::cout << "x: " << x << " y: " << y << "

";

return 0;

}

void myFunc(unsigned short int x)

{

return (4*x);

}

4. BUG BUSTERS: What is wrong with the function in the following code?

#include <iostream>

int myFunc(unsigned short int x);

int main()

{

unsigned short int x, y;

x = 7;

y = myFunc(x);

std::cout << "x: " << x << " y: " << y << "

";

return 0;

}

int myFunc(unsigned short int x);

{

return (4*x);

}

5. Write a function that takes two unsigned short integer arguments and returns the result of dividing the first by the second. Do not do the division if the second number is zero, but do return –1.

6. Write a program that asks the user for two numbers and calls the function you wrote in Exercise 5. Print the answer, or print an error message if you get –1.

7. Write a program that asks for a number and a power. Write a recursive function that takes the number to the power. Thus, if the number is 2 and the power is 4, the function will return 16.