CHAPTER 5

Story Building

A story is the expression of how and why life changes. A story begins with balance, then something throws life out of balance, then a story goes on to describe how balance is restored.

—Robert McKee

What Is Story?

As humans, we think and learn in terms of story. Story is intrinsic to being human.

The act of recounting stories involves drawing upon memories, which are stored in our right brain. Our right brain also gives us both social and emotional context for those memories. Building language around our memories and creating logical explanations, on the other hand, is the left brain’s job; thus, storytelling is a whole-brain process. There’s the mental detective work of piecing together the structure of a story and the emotional detective work of figuring out how we feel about it, how we convey those feelings, and what points we are making. As Dr. Daniel Siegel puts it, “When the left-mode drive to explain and the right-mode nonverbal and autobiographical processing are freely integrated, a coherent narrative emerges.”

Change Is at the Heart of Story

If story is the expression of change in life, then an understanding of how change occurs will help us build our stories. Researchers who study change have made an interesting discovery about how passengers on sinking ships behave. Common sense suggests that passengers would jump into lifeboats as soon as they learn their ship is sinking. But that’s not the case. In fact, most passengers do the opposite: they remain on board until the last possible moment. The reason? Fear of the unknown. Passengers are able to rationalize not getting into the lifeboats by kidding themselves, by inventing scenarios in which the ship might stop sinking. Their line of thinking is: “This ship is still above water. I don’t know anything about that lifeboat. I’m not jumping until I have to.”

Fear of the unknown is what prevents us from changing. Think of times in your life that you haven’t changed even though you knew you should have, times you maintained the status quo out of fear of the unknown.

Change is slow. We resist it. It’s part of human nature. Most of us change only when we feel we have to. We attempt to rationalize the status quo (“This ship is still above water”) until we are forced to acknowledge that the status quo is untenable (“My feet are getting wet!”).

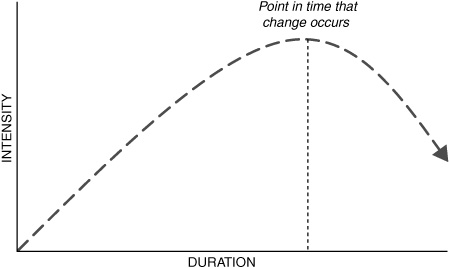

The arc of change (Figure 5.1) presents a model of how things in life change. The line represents the intensity, over time, of the pressures that influence a given change. The peak of the line represents the point of change. Note that the change occurs only after a lot of pressure has built up over a lot of time.

Not coincidentally, models of story structure express a similar arc. In fact, experienced storytellers will tell you that story and change are inextricably linked. Viewed in this light, the study of story is also the study of how and why humans change, which is very relevant to sales. On the most basic level, selling requires people—our customers— to change, to overcome the fear of the unknown. As salespeople, then, it’s important that we understand how change occurs in order to influence others.

In this chapter, we’re going to give you a framework for recounting and building your stories step by step. It might not feel natural, especially at first. But the more stories you build, the more you’ll begin to use this framework to think of your experiences in “storiable” terms.

Ben’s Story: How Could I Ever Be a Storyteller?

One evening, Mike and I were sitting around at his house talking about the very best storytellers we knew.

“My grandmother,” Mike said without hesitation. “Hands down. I remember how her stories would paint a picture in my imagination. I’d smell what she wanted me to smell, taste what she wanted to me taste, see what she wanted me to see. Her stories were full of color, dialogue, suspense, and emotion.”

Mike is a good storyteller himself. It made sense to me that he’d grown up in a family with an oral storytelling tradition. I didn’t give it much thought until a few days later, when I was struggling with a story I wanted to tell a prospect.

Then it hit me. “Oh no,” I thought. “I didn’t have a grandmother who told me stories like that. I didn’t get those bedtime stories. What if you need to be raised on stories in order to become a good storyteller?”

I was shaken—so shaken, in fact, that I left off studying story structure for the time being and began investigating how people actually learn about story. I wanted to know if I’d missed the boat. I wanted to know if I had any hope of ever being a good storyteller.

A few weeks later, I stumbled across an encouraging quote from Daniel Siegel in his book Mindsight: “We all make sense of our lives through stories.”

I kept reading. It turns out that story building is an intrinsic human process. We are all genetically wired to think in stories—even me.

The difference between Mike and me was, his upbringing had cultivated the storyteller in him, whereas the storyteller in me had been largely dormant all those years—a situation that was no doubt exacerbated by the fact that I’d chosen a career in business, where so much of our training and work is logical and analytical.

But the capacity for storytelling was still inside me. I just needed to discover and nurture my inner storyteller. And thanks to what I’d learned about neuroplasticity—about the brain’s constant change and growth, even in adults—I was no longer discouraged. We all have the ability to “rewire” ourselves. I’d been on the right path to start with. With the right help, I could be a good storyteller.

Anybody could.

The Basics of Story Structure

You already know more about story structure than you might think you do. For instance, you probably know—intuitively, at least—that stories have a beginning, a middle, and an end. You know that they have characters and a plot. And you know, from personal experience, that not all stories are created equal. Some stories are simply more moving, memorable, and powerful than others. The secret to building a good story lies in what Edgar Allan Poe called the “unity of effect or impression,” where all the elements of a story—characters, plot, setting, emotional tone, and so forth—work together to achieve the story’s effect. Here is the Story Leaders framework that will help you build a good story by incorporating all the elements of a story to make your point.

The Point

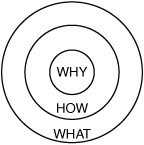

Start with the point. As Simon Sinek observes in his book, Start with Why, we process information from the inside out. His Golden Circle diagram (see Figure 5.2) depicts three concentric circles: the inner circle is the why; the middle circle is the how; and the outer circle is the what.

Figure 5.2 Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle

Source: www.startwithwhy.com

His theory is that the best leaders think and communicate from the inside out, starting with the why. Sinek points out that such an approach maps directly to the processing of the mind from the inside out: everything starts with the limbic system (the emotional brain) and goes outward to the neocortex (the thinking brain).

So it makes sense that as sellers, we should organize the ideas we want to communicate to buyers from the inside out. The inside (the why) is a belief. Before you build a story, what is the why of the story? Or in story terms, what is the point of the story? Before you build a story, ask yourself, “What point do I want to make?” A point is a belief—the why.

For instance, you might want to make a point such as: Believe in yourself. Never give up. Good conquers evil. Don’t judge a book by its cover. There is a better way. The point you want to make will depend on your specific sales situation, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 6.

The bottom line is, if you don’t have a point, you don’t have a story. We’ve had workshop participants tell us, “I’ve told stories before, but I never thought about making a specific point. Now that I think about the point I am trying to make ahead of time, I’m a much better storyteller.”

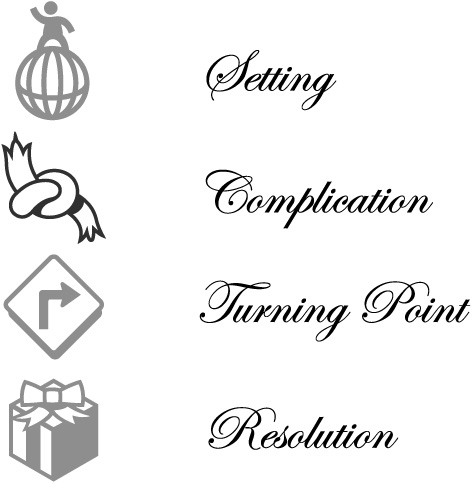

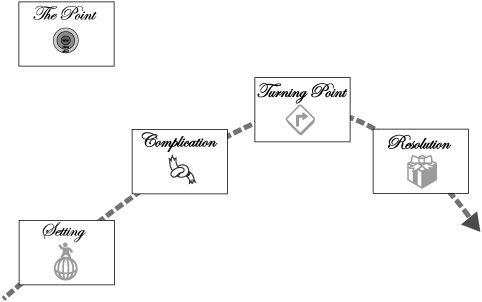

Once you know what point you’re trying to make, you can build a story that makes the point. The other basic components of story we teach in our workshops are defined here and shown in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 The Elements of a Story

The Setting

The setting is the beginning of the story, including its time, location, and any relevant context or conditions (e.g., weather, business, politics, and so on). The setting also provides the introduction to the characters. Every story, even a short story, has at least one character. The setting sets up the journey— how it begins.

The Complication

The complication encompasses most of the events of the story and how they complicate the lives of the characters as they face challenges and conflict. Without a struggle, there is no plot; without a plot, there is no story. Sometimes it’s an external struggle, between characters or between a character and outside forces, and sometimes it’s an internal struggle, a character in conflict with herself as she tries, for instance, to resist a destructive urge or to stick to her principles. In all cases, the complications reveal a character’s vulnerability and may include “dumbass moments” like we discussed in Chapter 3.

Often, a character’s vulnerability involves shame. If you’re telling a story about yourself, owning up to your shame takes a lot of courage. It’s worth it, though. When you reveal your shame, your listener will connect with your human imperfection. In this way, having the courage to reveal shame reflects what Daniel Goleman calls “emotional intelligence,” which is characterized by self-awareness, social awareness, and effective relationship management.

The Turning Point

The turning point is the emotional peak of the story, where the character has an aha moment, a change in perspective, or a change in direction. Things come to a head when a character makes a decision or takes an action that changes the anticipated outcome of the story.

The Resolution

The resolution is the final outcome of the story, the untangling of events that reveals how the complication is addressed. Think of the setting as “before” and the resolution as “after.”

Story Building

Remember Robert McKee’s definition of story: “Story expresses why and how life changes.” Building stories is the process of putting language around why and how life changes.

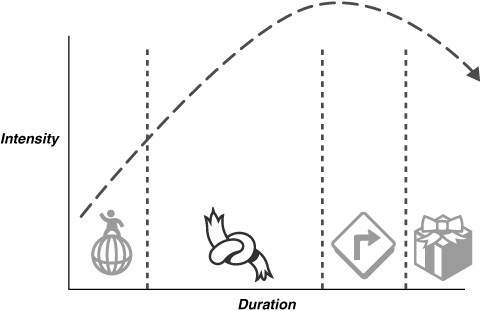

If we map the elements of a story onto the arc, we get a visual representation of a traditional story plot (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 The Elements of Story Along the Arc of Change

A successful story needs a plot that shows change, but it also needs something else: emotional impact. Stories that are too factual lack emotion and therefore lack the power to influence change. Stories that are too emotional lack coherence and don’t make sense. In the following pages, we’ll tackle the process of story building in two parts that will integrate and balance left- and right-brain processing. First, we’ll show you how to use the Story Leaders card system to build stories that follow the arc of change. Then, we’ll explain how to give your stories emotional impact.

Part I: The Story Leaders Card System

When we teach story building in our workshops, we storyboard our ideas using colored index cards to represent the structural elements of a story. We’ve found that the different colors (yellow, red, green, white, and blue) help people remember the elements better than if we used white index cards. By the end of the workshop, participants even start speaking in card colors: “I love my yellow card, but I’m still struggling with my white card.” For the purposes of this book, we’ll be using the icons in Figure 5.3 to represent the different cards. You can purchase your index cards at any office supply store, and you can download our template from the Story Leaders website that will allow you to print out a “storyboard” in color. Just visit www.StoryLeaders.com/downloads and click on “Download Storyboard.”

The goal of the card system is to help you build stories one structural element at a time (see Figure 5.5). The cards ensure that your story has all the necessary “ingredients” and are intended to serve as a storyboard, not a script. The idea is to make brief notes and/or bullet points to jog your memory when you practice it aloud later. Think of the cards more as a map of your story, a lightweight framework, not as the story itself.

Figure 5.5 How the Cards Correspond to the Arc

No need to worry about good grammar or complete sentences. You don’t want the language center of your left brain getting in the way. For the same reason, we also encourage you not to build your stories on a computer. When you write by hand, you are using your right brain, which is connected to your five senses and to your emotional brain. When you’re typing on a computer, your left brain—with its built-in spell checker and grammar police—is more likely to interfere.

For the sake of coherence, we have found that it’s best to build a story by working backward, in the following order:

1. The point of the story (yellow) ![]()

2. The story’s resolution (red) ![]()

3. The story’s setting (green) ![]()

4. The story’s complication (white) ![]()

5. The story’s turning point (blue) ![]()

Starting with the point might seem counterintuitive at first, but it’s really not. Our brains don’t store memories in chronological order. Rather, memories are filed according to the meaning and emotions we associate with them. By working backward, we’re building stories in the same way that our brains organize and recount memories.

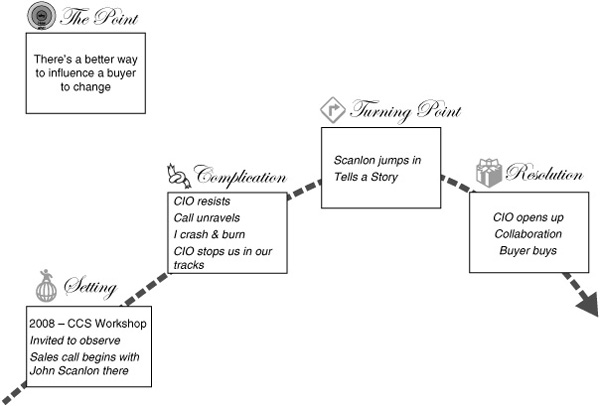

(Re)building Ben’s Story: John Scanlon

Remember Ben’s story about John Scanlon at the beginning of Chapter 1? It’s a story that helps explain what led Ben to question our old model of selling and, ultimately, what led to the book you’re now holding in your hands. For the purposes of illustration, we’re going to “rebuild” that story here using the cards.

Yellow Card: The Point of the Story

Yellow Card: The Point of the Story

The first thing to ask yourself as you begin building a story is, “What’s the point?” What is the moral? What belief do you want to communicate? What is the why? The yellow card represents the point of your story. In Ben’s story about John Scanlon, Ben’s point is, “There is a better way to influence a buyer to change.”

Red Card: The Story’s Resolution

Red Card: The Story’s Resolution

The story’s resolution is its ending—the part of the story that drives home your point.

In the John Scanlon story, the resolution comes when the CIO agrees to do the deal. Ben sits there in confusion, astonishment, and embarrassment, having witnessed John build connection and trust with the CIO.

Another example: Suppose you want to make the point that you are trustworthy—your yellow card. So you look back on your life for a story that illustrates that point. You remember a time when you returned a wallet you found in a taxicab in New York, a wallet that contained a substantial sum of money. You now have the ending of the story. Jot it on your red card.

Green Card: The Setting

Green Card: The Setting

The green card represents the story’s beginning. It’s the setup: When and where does the story take place? Who are the characters (e.g., the hero)? What sets the action in motion? And what background information is needed to provide context for the story?

Ben’s story about John Scanlon takes place in 2008 after a CustomerCentric Selling workshop, when Ben is invited by his student Jason to observe a sales call. The main characters are Ben, Jason, John, and the CIO buyer. What sets the action in motion is John’s unexpected presence at the meeting. The context includes the fact that Ben has trained everybody in the company except John, and that he’s looking to “showcase his stuff” during this particular meeting.

Building stories can be difficult, but life is kind to storytellers in that it often presents natural beginnings and endings. Take advantage of them. In Ben’s story, Jason’s invitation during the sales training workshop provides a natural beginning. In the story about returning a wallet, the natural beginning would be finding the wallet.

Providing context for a story is also critical. Compare these two story settings for a story about a service call.

1. “It was late Friday afternoon when we got a service call from our biggest customer. Their system was down, and they were losing money by the minute . . .”

2. “Last summer, our engineers were almost burned out. They’d just released a new product after months of hard work and overtime. Our lead engineer, Robert, had told the guys they could leave early, and everybody was relaxed and happy, looking forward to a long holiday weekend with no deadline looming. Then we got this call . . .”

The second setting is much more powerful because it provides more context, so we have a better understanding of what’s at stake. We also get a sense of the engineers as human beings we can relate to. Compare that to the first beginning, which offers little in the way of context or characters.

In order for a listener to care about your story, he or she has to care about the people in it. Take Ben’s story, for example. We care about what happens in the sales meeting because we’ve “met” Ben and appreciate his situation— his pride in his teaching, his desire to “showcase his stuff.” We’ve also met and care about Jason, who is so confident about what he learned in the workshop that he invites his instructor to observe him in action.

Providing context is important, but be careful not to overdo it, or it can bog down the story. Ben’s story is about 850 words long. He establishes the setting and gets the action under way very efficiently—in about 100 words. But if he’d spent another paragraph or two going on about what happened before the Scanlon meeting, we might have lost interest before he ever got there. It’s a matter of proportion. Ten or 15 pages of setting at the beginning of a 300-page novel isn’t unreasonable, but you don’t have that kind of leeway when telling a story to a prospect.

White Card: The Story’s Complications

White Card: The Story’s Complications

Complications are the obstacles and challenges that a character faces between the story’s beginning and its turning point (or “climax”). Complications are what make our stories interesting. They create tension and suspense through conflict. Sometimes the conflict is external—between characters, or between a character and outside forces—and sometimes it’s internal, a character in conflict with himself. In the story about the wallet, for example, the absence of ID would represent an external conflict where circumstance complicates the hero’s efforts to return the wallet. If the hero is tempted to keep the money for himself, that would represent an internal conflict pitting the hero’s desires against his values.

Stories in which you, as the main character, are in conflict with yourself can be especially powerful because they present an opportunity to share your imperfections and reveal your vulnerability—which, as we know from Chapter 3, is our most powerful way of getting another human being to open up to us. Stories with characters who lack vulnerability tend to be less compelling. A story about a do-gooder who finds a wallet and returns it with no hesitation isn’t nearly so interesting—or so human—as a story about an otherwise good person who is nonetheless strongly tempted to keep the money. Likewise, in our service call example, a story of a superhuman tech support effort will have much less impact than one in which you acknowledge that your firm made mistakes but then you made good on your promises.

Remember, no one connects with perfection. Portray yourself as human, vulnerable, and flawed like the rest of us. The character (you) should be someone the listener can relate to and sympathize with, someone who is not immune to having a “dumbass moment” now and then. This is a phrase we use in our workshops to refer to our own screw-ups, moments when we make mistakes or are resistant to change. In the wallet story, the dumbass moment is when you let yourself get seduced by the money and start thinking about all the great stuff you’re going to buy.

In Ben’s story about John Scanlon, the complications begin when the prospect doesn’t respond well to Jason’s sales pitch: “Within minutes, the call flipped: Jason was no longer the one asking the questions. The CIO had taken over the interrogation, and Jason was responding by talking about what his products do, the very thing we try to avoid early in a conversation.” Ben’s dumbass moment comes when he interjects himself into the sales meeting, using a traditional selling model—only to crash and burn.

Blue Card: The Story’s Turning Point

Blue Card: The Story’s Turning Point

The turning point (or climax) is often the most difficult element for beginning storytellers to pinpoint. There’s a tendency to think of the ending as the turning point. For example, in the service call story, a novice might think the turning point is when the customer’s issues are resolved. Actually, that would be part of the resolution, along with the customer’s reaction to the level of service. The actual turning point would come when, one after another, the engineers volunteer to stay late and work on the problem. In the wallet story, the turning point isn’t when you give the wallet back to its owner. Rather, it’s the moment you decide not to keep it because you once had your own lost wallet returned to you, or because you consider how you’d feel if it were your daughter’s wallet, or whatever the case may be.

To locate the turning point in a story, look for a key decision, event, or action, the moment when the main character changes the expected outcome of the story. In Ben’s story, the turning point comes when John speaks up in the meeting— and proceeds to save the day with his storytelling.

Storyboard

Once you have all the structural elements of a story, it’s time to create a visual representation of the plot by arranging the cards in chronological order (see Figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6 How to Lay Out Your Index Cards (John Scanlon Storyboard)

Part II: The Language of Emotion

Up until now, we’ve focused on the left-brain part of story building: mapping out the structure, making it coherent. Now comes the right-brain part: developing the story’s emotional dimension. Think of it as taking your story from 2-D to 3-D.

Our goal is to tell stories that move the heart, not just the head. Stories that lack an emotional impact get labeled by the brain as unimportant. There is a direct correlation between emotional intensity and memory. The experiences we remember best and longest are the ones that have a profound emotional impact on us—for example, experiences that really make us feel good, or experiences that really hurt us. Not only will emotion allow you to move the heart, it will also enable you to tell your story from the heart.

The power of emotion in story is reflected in the following old Jewish parable.

Truth and Story

A long time ago in a small village lived two girls, one named Truth and one named Story. Each wanted to be the most popular girl in the village. Soon a rivalry developed between them. They decided to settle the question once and for all with a contest. Each girl would walk through the village. Whichever girl was greeted by the most villagers would be the winner.

Truth went first. She set off down the cobblestone street, passing through the heart of the village. Not one person came out to greet her. By the time she reached the other end of town, she was devastated.

Story went next. She had taken only a few steps before people began coming out of houses and shops. “Story, how are you?” “Story, good to see you!” And so it went until she had passed through the village and reached Truth, who was in tears.

“Story,” said Truth, drying her eyes. “You win. You are the most popular girl in the village. Everyone likes you. But why?”

Story put her arm around Truth’s shoulder. She spoke in a consoling voice. “You and I,” she said, “we are not so different. I have Truth in me, too. But nobody wants to hear the naked truth.”

“So what am I supposed to do?” said Truth.

“Here,” Story said, removing her cloak. “Take this, and wrap yourself in it.”

“What is it?” Truth asked.

“Emotion,” Story said. “Wear it, and you, like me, will become Story.”

From 2-D to 3-D

Dr. Jerome Bruner observes that stories entail two levels of narrative: (1) the external narrative of a sequence of events, which involves left-brain processing, and (2) the internal mental and emotional narrative of the characters, which involves right-brain processing. At this stage, you’ve built the first level, but your storyboard is still little more than a map, literally a two-dimensional representation of a story. Now we want you to look at the story and figure out how you feel about it. Put some energy into developing the emotional life of your characters. In doing so, you’ll be adding a figurative third dimension—emotion.

This part of the chapter is a lot shorter than Part I, but don’t be fooled. Putting language around emotion can be really difficult. For one thing, most of us, particularly males, just aren’t used to doing it. In our left-brain schooling and jobs, we’re encouraged as often as not to avoid bringing emotion into the equation.

Fortunately, there are approximately 6,000 words in the English language that represent emotion. The language of emotion is there for the taking. Consider this small sample:

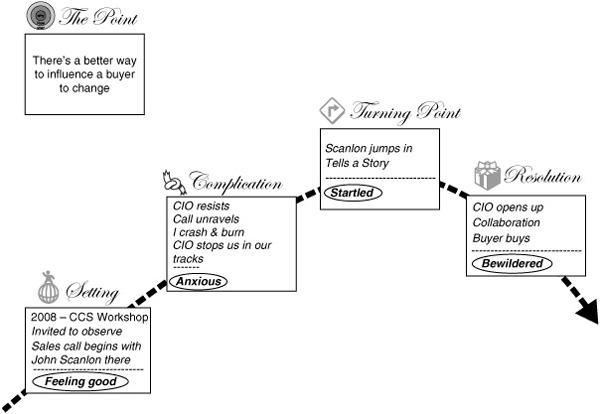

The next step is to write down emotions at the bottom of each of your cards, excluding your yellow card (the point). The emotional journey within a story is what delivers the point, what will make the listener remember your story, what gives it its impact. In this sense, the real meaning of your story is embodied in its emotional dimension. That’s the part that has the power to influence change.

Start with your green card (setting). Ask yourself, “How did I [or the character] feel at this point in the story?” Name the emotion. Now jot it down, just a word or two at the bottom of the card. Feel free to use the preceding list to help you find the words. If the emotion was strong, write the word in big letters or in caps. If the emotion was less intense, write the word smaller. (Remember, the cards are a visual representation of your story. The more visual aspects you incorporate, the more readily your visual right brain will soak it up and remember it.) For good measure, circle the emotion word. Now repeat the process with your white card, then your blue card, and then your red card.

Ben’s storyboard appears again in Figure 5.7, this time with emotions added at the bottom of the cards.

Figure 5.7 Ben’s Storyboard with Emotions Added to Cards

The Natural Story Builder in You

The process of building a story using the cards might seem left brain and mechanical. For most people, applying any new framework is uncomfortable at first. What feels unnatural and complicated becomes, through practice and repetition, fluid, even second nature. And with story building, it is human nature to think in story. We’re intrinsic story thinkers. The cards do what good storytellers do intuitively—they shape experiences into stories. It’s not like you’ve never done this before. You’ve been doing it all your life, just not as consciously. With a little practice, you’ll be doing the whole process in your head, on your mental index cards. In the workshop, we find that people quickly pick up the card system and after a few stories can visualize the cards and build their stories in real time. It’s really just a matter of recounting events and imbuing them with the language of emotion: “What changed? Why? How did I feel?”