CHAPTER 6

Stories for Selling

People who tell the stories rule the world.

—Plato

Believe What I Believe

Selling isn’t just a matter of getting buyers to purchase goods and services. On a more fundamental level, it’s about influencing people to change—influencing them to believe what you believe. This isn’t just what great salespeople do; it’s also what effective leaders, teachers, politicians, coaches, and lawyers do.

Who are the greatest leaders in American history? When we ask this question in our workshops, Abraham Lincoln is always one of the first names we hear. As a leader, Lincoln more than had his work cut out for him. Imagine trying to sell abolition to a nation that was in large part economically dependent on slavery. Imagine trying to hold a nation together even as it sank into a civil war.

Fortunately, Lincoln was a renowned communicator, a skilled orator and writer who understood the power of story. “Instead of berating the incompetent generals who blundered in the Civil War’s early battles,” writes author Jeff Beals on his blog, “Lincoln educated and motivated them by using stories. To smooth over ruffled political feathers with members of Congress, Lincoln would pull out a story and use it to establish common ground.”

Lincoln himself was very conscious of the power of story to “sell” his ideas and beliefs. Here he is in his own words, quoted in Lincoln on Leadership: Executive Strategies for Tough Times by Donald T. Phillips:

I believe I have the popular reputation of being a story-teller, but I do not deserve the name in its general sense, for it is not the story itself, but its purpose, or effect, that interests me. I often avoid a long and useless discussion by others or a laborious explanation on my own part by a short story that illustrates my point of view. So, too, the sharpness of a refusal or the edge of a rebuke may be blunted by an appropriate story, so as to save wounded feelings and yet serve the purpose. No, I am not simply a story-teller, but story-telling as an emollient saves me much friction and distress.

Politics is certainly not the only profession in which leaders sink or swim based on their ability to influence others with stories that serve a purpose. In the legal profession, lives often hang in the balance as lawyers attempt to bring judges and juries around to their way of thinking. Consider the infamous O. J. Simpson trial. In 1995, Robert Shapiro’s legal defense team stunned the world by convincing a jury that O. J. Simpson was not guilty of murdering his ex-wife, Nicole Brown, and her friend Ronald Goldman.

How did they do it? As Shapiro explains in his book, The Search for Justice: A Defense Attorney’s Brief on the O. J. Simpson Case, the defense team began the trial by “launching into a relationship with the jury”—a relationship that was established using story, starting with a riveting opening statement. The defense team proceeded to reconstruct the story of O. J. Simpson’s life in the hours leading up to the murder. Evidence played a role in the story, but so did emotion—what Simpson was thinking and feeling. The lawyers even brought in passengers who’d been on the same flight as Simpson to describe his emotional state prior to arriving in Los Angeles on the day of the murders. In short, the defense team knew that they needed to humanize Simpson, and they knew that story would be the most effective way to do this.

Ben’s Story: “What Are You Talking About?”

After I read Shapiro’s book, I gave him a call. I wanted to ask him about his use of story as a way to influence juries to believe what he needed them to believe. Unfortunately, I made the mistake of telling him right off the bat that I’d read his book about the O. J. case—the same book in which he mentions his disdain for interviews about the O. J. case.

“What do you want to know?” he said, already impatient.

I started to tell him that I believed storytelling was underused in our society, but he cut me short.

“Underused?” he said. “What are you talking about? There’s nothing ‘underused’ about storytelling. It’s exactly what we do in the courtroom. It’s what we’ve always done.”

Before I could get another word in, the conversation got interrupted and Shapiro said he had to go. The call had lasted barely two minutes. I was disappointed I didn’t get more time with him. I’d been hoping to interview him. Instead, it basically felt like he’d said those of us in the corporate world are idiots.

It wasn’t until that night, as I was telling my wife about the call, that it hit me: Shapiro had told me everything I needed to know. His basic message was, “Maybe you geniuses in corporate sales haven’t figured out the power of storytelling yet, but the legal profession has—a long time ago.”

And he was right.

Stories for Selling

Whether you’re promoting an idea, a belief, a point of view, a product, or a service, the goal is the same—to influence others to believe what you believe. It’s all a form of selling.

In this chapter, we’re going to discuss how stories can help you sell and how to figure out what types of stories you’ll need in your repertoire. The process begins by considering your customers’ buy cycle. At the end of the chapter we’ll present four real-life “stories for selling” and illustrate how they were composed using the story-building techniques from Chapter 5. We’ll close by discussing the particular challenges of prospecting and explain the best way to use a story when you have only seconds to pique a stranger’s curiosity.

Mike’s Story: Getting Buyers to Open Up

When I began selling first-generation MRP systems in 1975, I had no formal sales training, but I had put in more than 7,500 hours helping our customers at Xerox Computer Services use our integrated set of hosted business software applications to run their businesses. Specifically, I helped people such as controllers, payroll managers, accounts payable supervisors, chief financial officers, and materials managers do their jobs better.

Over time, I came to know the most common needs of these and other specific positions in manufacturing companies. So when I met a new prospect, I’d tell a story about how I’d helped someone else with the same job title, what that person went through, and how she addressed her needs using our system. It was one type of story that almost always got the buyer to open up and share her issues with me: “Hey, I’m in a similar situation myself. . . .”

The only reason I used a story is because, with no formal sales training, that’s all I had. I’d previously worked the customer help desk, so I knew all of our customers’ stories—practically every imaginable issue and the ways our systems had helped resolve them. Using the stories was simply intuitive.

Unfortunately, I didn’t make a point of using stories after the initial sales call, and the rest of the sales cycle tended not to be as smooth or predictable. I didn’t realize at the time how valuable the stories were. I thought a story was merely a starter, a way to get someone to open up. Knowing what I know now about how people respond to stories, I think about some of my old prospects and imagine how much more successful I would have been if I’d used stories throughout the entire sales cycle.

Stories with a Point

Think about the stories you already tell in your personal life and the points of those stories. Most of us have some humorous stories in our repertoire—stories we use to break the ice at parties, to make people laugh. Maybe there are other stories you tell as a way of offering advice to friends. Maybe you tell some stories that function as cautionary tales, intended to help people not make the same mistakes you’ve made. If you have kids, you likely tell bedtime stories. And probably there are stories that you tell simply to make a point.

In building an inventory of stories to influence buyers, we want you to make sure that all of your stories have a point. A good way to start is by considering your customer’s buy cycle. What are the steps, or gates, your buyer goes through that lead to a buy decision? A buy cycle might include any number of steps, depending on the particulars of your industry, the size of the potential sale, the length of your customer’s buy cycle, how many people are involved in the decision-making process, the complexity of what they’re looking to change, and so on.

The Buy Cycle

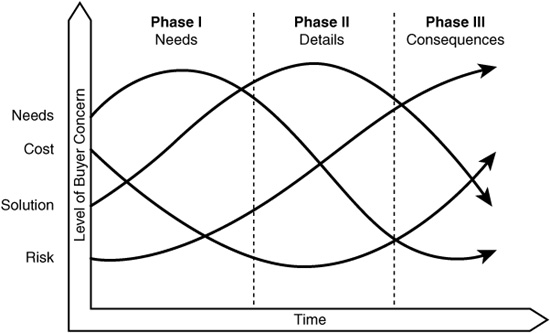

As part of the original SPIN research project at Xerox, Neil Rackham studied the behaviors of buyers over time. The research pointed to a set of priorities buyers typically need to address and how these priorities take on various degrees of importance throughout the buy cycle. Figure 6.1 is an adaptation based on his study of the buy cycle.

Early in a buy cycle, the number-one priority in the mind of the buyer is his or her needs. Once a buyer has acknowledged a set of needs, he then shifts to phase II, in which the priority becomes evaluating how to address those needs (the details). And once a buyer considers all the options and determines how to address his needs, he moves into phase III, the decision to take action, to jump or not to jump into the lifeboat. Notice that as the buy cycle progresses, the risk of change becomes increasingly significant in the mind of the buyer, ultimately ranking as the top priority in phase III. This buy cycle occurs universally; however, depending on the complexity of the product or the magnitude of change involved, there can be multiple decision points in each of the three phases.

Sample Buy Cycles

The following are a couple of real-life buy cycles.

Business-to-Business Buy Cycle Here’s a long buy cycle in a B2B selling environment. The client is a large enterprise software company. The average sales cycle is six months, and the average sale is $250,000, sold to a committee of buyers.

1. The buyer becomes curious about a new approach.

2. The buyer expresses a set of needs.

3. The buyer is willing to brainstorm new ways with someone he trusts.

4. The buyer sees a new way (the solution).

5. The buyer must get a committee of others to agree to consider change.

6. The buyer understands the value of the new way versus the cost of maintaining the status quo.

7. The buyer sees a path to implement.

8. The buyer makes a decision to act, to sign, to commit.

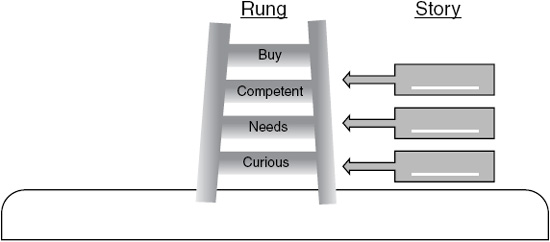

In reverse order, the steps of a buy cycle can be thought of as the rungs of a ladder, where the top rung represents the decision to buy (see Figure 6.2).

B2B Story Ladder example

Figure 6.2 Enterprise Buy Cycle

B2C Story Ladder example

Business-to-Consumer Buy Cycle Here is a buy cycle we helped another client develop—a financial firm that sells in a business-to-consumer (B2C) environment. The firm sells investment services in a highly competitive marketplace and typically wins new clients in a single meeting (see Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 Business-to-Consumer Buy Cycle

1. The buyer expresses curiosity.

2. The buyer expresses needs.

3. The buyer achieves confidence that the advisor is competent and trustworthy.

4. The buyer agrees to buy.

The Story Ladder

The goal of sellers at the B2B enterprise software company was to influence buyers to progress through the eight steps shown in Figure 6.2, one rung at a time, culminating with a decision to buy. It’s like a pilot flying across the country. The pilot doesn’t simply set his navigation system to go from Los Angeles to New York. Rather, he uses a set of vectors, flying from point to point in order to avoid getting off course.

Think about what your buyer’s vectors would be—the rungs on the ladder. Each rung represents a belief or idea your buyer must arrive at before proceeding up the ladder to the next rung in his or her buy cycle. In this chapter, you’ll begin to identify an inventory of stories whose points will guide your buyer to the desired belief or idea at each rung.

In order to make use of a story ladder, you will need to build an inventory of stories that help you deliver each of the points you want to make—points that correspond to each rung in your customer’s buy cycle. The stories will help your buyer open up and talk about those points. For instance, a story about needs is designed to help the buyer share his needs; a story about solving a problem for another buyer would encourage the buyer to talk about the best solution for his particular problem; and so on. The key is to ask yourself at each rung, “What point do I need to make at this stage in the buy cycle?”

Connection and Trust

If a buyer works for a company that has a procurement process, she’s going to be looking at multiple vendors. The expectation is that she will logically consider all of the variables and make the best buying decision—a left-brain decision. At least that’s how we always thought it worked. But research now tells us that the very act of saying yes—of saying, “I trust you, I like you, I’m going to take a leap of faith and do business with you”—is in fact a right-brain activity. In other words, buyers don’t necessarily make logical decisions. More likely, a buyer makes an emotional decision to say yes to the vendor she trusts—the one with whom she has formed the strongest emotional connection—and then she justifies that decision with logic after the fact.

Therefore, a seller’s first and foremost goal should be to make an emotional connection with a buyer. Years after his sales stint at Xerox, Mike finally “got” why his intuitive approach had worked so well. Using the power of story, he had been forging emotional connections with his clients.

In almost all selling situations, the first question buyers ask themselves is, “Do I trust this person, or is she like every other salesperson?” In the examples shown in Figures 6.2 and 6.3, the first two rungs of the story ladder are (1) curiosity, and (2) needs. If buyers don’t trust you, they aren’t going to be curious about what you’re selling, and they aren’t going to admit their needs to you. (We’ll talk more about curiosity later in the chapter.)

Because curiosity, connection, and trust are so essential in almost all sales cycles—whether it’s a B2B enterprise sales cycle or a B2C “one-call close”—we believe sellers should have a minimum of three basic story types in their repertoires:

1. Who I Am story

2. Who I Represent story

3. Who I’ve Helped story

Real-Life Examples

Here are four real-life stories—plus the stories behind the stories. We’ve also included the storyboard each seller developed using the Story Leaders card system explained in Chapter 5.

The Who I Am Story

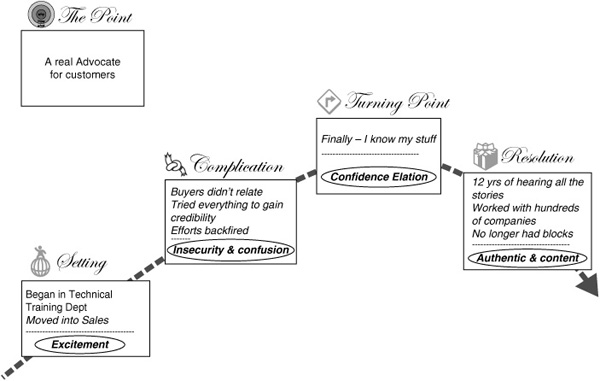

The Who I Am story is about your journey—how you ended up here today. The point of the story is to demonstrate why you are doing what you’re doing. The resolution of this story is what you currently do and should illustrate the point. Once you have the resolution, you will find a natural beginning. Then search out your complication(s) and turning point.

Linda’s Who I Am Story It was the first day of the Story Leaders workshop, and we’d come to the exercise where we were supposed to write our Who I Am story. At first I thought, I can write a simple story about myself. This should be pretty easy. But as soon as I put pen to paper, I froze. I had nothing. I started to freak out. The minutes were ticking by, and everyone else in the room was writing. Eventually, I just forced myself to start writing. At the end of the allotted time, by some miracle, I had a story. It was about why I went into sales and how I’d always been a person who cared about my customers.

The next thing I knew, Ben was asking me to share my story. My heart started racing. Why me? I thought. Why are you asking me? But I didn’t want to look like a baby, especially with my vice president in the room, so I did it. I told my story. Basically, I said I’d gone into sales because I’d always cared about my customers and really wanted to do what was best for them. I described myself as a solution-based customer advocate, et cetera, et cetera. As I was telling the story, I realized it wasn’t any good. There was no transformation, no lesson learned, no complications, and no dumbass moment. It wasn’t a Who I Am story so much as a Why I’m So Great story. I hadn’t intended it that way; that’s just how it turned out.

I expected Ben to tell me the story needed a little work and then move on to the next person. Instead, he took me back to the very beginning of the exercise.

“What’s the point of your story?” he said.

“I guess the point is that I care. I believe my role is to be an advocate for customers.”

“Okay,” he said, “and what’s the red card, the resolution?”

“That I have all these years of expertise and I’m here to serve the customer.”

“How about the green card, the beginning of the story?”

“I started in technical training,” I said. “I wanted to get into sales because I thought I could have a bigger impact.”

“All right. We have the point, the beginning, and the end. So now it’s just a matter of figuring out the complications and the turning point.”

I avoided looking at my VP. “I didn’t really have a complication in my journey.”

“Really? You’ve always been a great customer advocate, from day one?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I guess I didn’t really have the confidence when I first got into sales.”

“Keep going. Tell me more.”

“Actually, for several years, I felt people didn’t respond to me. I felt that buyers held me at bay. I got a lot of resistance from them.”

“Why do you think that was the case?” Ben asked.

“I’m not sure. I remember feeling insecure about it, though. In fact, I used to wear glasses to make myself look smarter. I worried a lot about my clothing, whether I looked the part. I was focusing on my own insecurities so much that it blocked me from being authentic and focusing on my customers. Pretty ironic, huh?”

“I didn’t feel like I was connecting with buyers,” I said.

“There was always a barrier. I wasn’t serving my customers the way I wanted. For years, I guess I was struggling for approval.”

“So there was a time you weren’t the customer advocate you wanted to be?”

Sure enough, there was my dumbass moment. Years of them. “I never thought about it that way until now,” I said. “But yes. There’s a huge difference between then and now.”

“So how did things change?”

“Well, I remember one day when I was on a sales call, I realized that even though I wasn’t connecting with the buyer, I completely understood his problem and knew exactly how to help him. And it dawned on me that by then I’d spent thousands of hours with my customers, and I really did know how to help them. I really knew my stuff. That’s what gave me the confidence to do what I’d always wanted to do—to stop worrying about my insecurities and start focusing on helping. A huge burden was lifted from my shoulders. I didn’t have to fake it anymore. Plus the whole experience made me a more empathetic salesperson.”

And there it was—I had my Who I Am story (see Figure 6.4). It was just a matter of using the cards to interrogate my flimsy Why I’m So Great story, to be more honest and self-reflective.

Figure 6.4 Linda’s Who I Am Storyboard

There’s more to the story. Fast-forward to one week after the workshop. I was invited to give a corporate-level presentation to a food and beverage company in Southern California. I reached out to a colleague who was going with me and floated the idea of opening the sales call with a story rather than cutting straight to the punch line, like we normally did. No response. I tried to introduce the idea again during our internal conference prep call, as we were going over the content, flow, handoffs, and so on, for the presentation. I got a lot of pushback from the lead account manager, who told me it was a bad idea. When he finally let me finish what I was saying, there was dead silence on the line. No one was comfortable with using a story on the sales call. They even decided that I shouldn’t be the one in charge of opening the call. I felt defeated, to say the least, and frustrated that I hadn’t been able to sell the idea.

When I expressed my frustration to my manager, who had attended the Story Leaders workshop with me, he gave the situation some thought and advised me to do the sales call my way, no matter what anyone else said. He reminded me of one of our colleagues who’d found himself in a similar situation and been vindicated by successfully using a good story. But unlike me, he was a senior vice president.

Even as I drove to the presentation, I was going back and forth about it. What can the sales team do? I asked myself. I’ll have the floor. But then: What if I bomb, and they refuse to ever consider my approach again?

At the presentation site, our sales team was sequestered in a conference room until our time slot on the agenda. While we were waiting, the six of us did a walk-through of the presentation. Still hoping to sway them, I tried out my story. The team wasn’t impressed. “Stick to the script,” was their advice. Our time slot was short. We’d been told to get in, do our thing, and get out.

Inside the main conference room sat eight senior executives, from senior VPs to C level. I focused on hooking up my laptop while the account manager quickly ran through introductions. She finished by saying, “Linda is one of our solution architects, and she’s going to lead off.” I looked up and saw eight men in suits with their arms crossed, leaning back in their chairs, looking like they’d prefer to be doing anything but listening to me. That’s when a lightbulb went on in my head: Tell them my story.

So I did it—I told them the Who I Am story I’d built in the workshop the week before. Before I knew it, they were uncrossing their arms, leaning in. Oh my God, I thought, it’s working!

The goal of our presentation was to get the clients to reconsider their decision to leave the product lifecycle management (PLM) project. It worked. After I told my story, everyone was more relaxed. The clients opened up and admitted they needed help. We left the conference room that afternoon with their commitment to reengage and clear steps to proceed. And not only had we achieved the results we wanted but the other members of the team complimented me on my delivery, recognizing that my story woke up the executives and had them on the edge of their seats.

The Who I’ve Helped Story

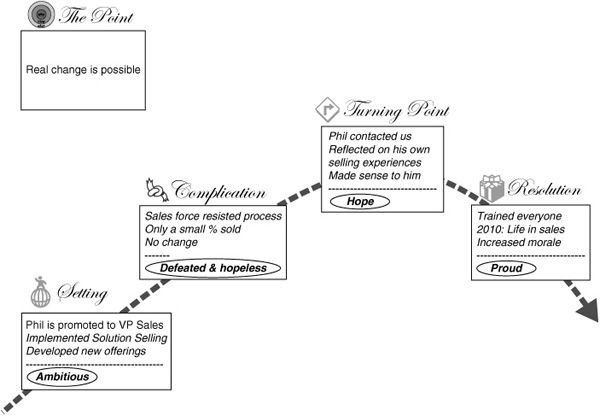

The Who I’ve Helped story is about the change that another buyer experienced as a result of buying from you. The point of this story is why he or she chose to buy from you. The resolution of this story is how he or she resolved any earlier complication(s). Once you have the resolution, you will find the natural beginning. Then search out your complication(s) and turning point. Here is one of Ben’s Who I’ve Helped stories about a Story Leaders client.

Ben’s Who I’ve Helped Story: Phil Godwin, Vice President of Sales, Clear Technologies Running a sales organization had proven to be a lot tougher than my client Phil Godwin originally anticipated. A few years ago, Phil’s company, Clear Technologies, was a stagnant IBM hardware reseller, and he was a frustrated vice president of sales. His company talked a big game, but they were still those guys presenting “speeds and feeds” and financial justifications in an attempt to upgrade their installed base—and getting nowhere.

When Phil was first promoted to lead his company’s sales organization, he implemented Solution Selling, the sales training Mike and I used to offer. He told me it was the only thing he knew to do at the time.

But after the implementation, the majority of his salespeople showed no improvement. In fact, he always had to fight just to get his salespeople to adhere to the sales process; they felt it was more for his benefit than theirs. He could forecast revenues better with the new process because they had pipeline milestones, but their selling behaviors never changed.

In an attempt to differentiate Clear Technologies from every other IT integrator, Phil’s company developed its own software offerings: a suite of automated storage reporting tools and security management software.

Still no change in sales.

Essentially, they’d replaced the word hardware with the word solution, but the way they sold stayed the same. In fact, only Phil’s top sellers figured out how to sell these new offerings, while everyone else continued to struggle. He’d really thought that by transforming what they sold— combined with the implementation of a sales process like Solution Selling—Clear Technologies would separate itself from all the clutter in the industry. But at the end of the day, nothing really changed. His top few sellers sold a lot, and everyone else remained the same.

Since Phil had been a Solution Selling client, he reached out to us. He shared his story with me, and I shared mine in return—the journey that brought Mike and me to found Story Leaders. At first, Phil was also skeptical. When I suggested he give our workshop a try, he was like, “Yeah, right. More sales training.” I remember asking him to tell me about the biggest sale he ever made, what sales process he used. He said he’d had no sales process; it was all about empathy, trust, and connection. That’s when he decided to take a leap of faith.

Today, Phil admits it was a big leap for him—a last resort, even. But it was a leap he’s glad he took. “We learned how to stop talking about our products so darn much and start communicating with stories—stories of our company, stories of our clients,” he told me. “I know that sounds weird, but it’s opened up channels I never would have expected. And it’s not just storytelling; it’s listening to our clients’ stories with a real intent to understand. That really has deepened our relationships with clients.”

Another thing that happened, says Phil, was that the employees at Clear Technologies emotionally bought into their company story—that is, once they figured out what the real story was. “We really have changed the company,” he said. “I would actually use the phrase ‘transformed the business.’” Phil’s salespeople began attending Story Leaders workshops in January 2010 and ended up having the biggest year in company history, even in a down economy—43 percent revenue growth in 2010 and in the first quarter of 2011. (For Ben’s Phil Godwin storyboard, see Figure 6.5.)

Figure 6.5 Ben’s Who I’ve Helped Storyboard

The Who I Represent Story

The Who I Represent story is about the journey of the company you represent. Just as every person has many stories to tell, every company has many stories, especially big companies with a long, complicated history and/or a wide range of product offerings. Resist the urge to present a time line of your company’s history. Instead, tell a more specific, focused story. The particular story you choose to tell about your company will depend on the point you’re trying to make. The resolution of this story is whatever your company does today that illustrates your point.

Before we train a company’s sales force, we like to meet with senior executives to learn the company’s story, which in turn becomes a salesperson’s Who I Represent story. Such was the case with a client of ours in 2011. Laura, the vice president of marketing, thought it would take about an hour to build her company’s story.

“We already know it,” she said. “It’s on our website on the About Us page, and our history and all the key milestones are well documented.”

But I’d seen the company history on the website. It was basically a time line, no more a story than the bullet points in Zoe’s teacher’s history lesson.

“I think it’s going to take longer than an hour,” I told her. “Can you clear your calendar for the day?”

Sure enough, it took us nearly the entire day. In addition to Laura, we had the vice president of sales, the CEO, and two marketing directors in the room. After some arm wrestling, yelling back and forth, and some black eyes, we finally emerged with a coherent story that conveys the company’s guiding beliefs.

“It doesn’t just tell what we do or how we do it,” Laura said. “It tells why we do what we do. This was the missing piece. I was always frustrated that our salespeople never bought into our story. I realized only now that was because we never communicated our story to them, none of us ever told the story about why we do what we do. We always led with the what and the how. We just gave them the facts. The new company story that we’ve developed has inspired our salespeople. Even our veteran reps tell us, ‘I never knew what a great company we were.’ It’s a real David versus Goliath story. It’s a story about the underdog. And it not only moves our employees, it moves our clients.”

Laura’s Who I Represent Story Our story begins in the late 1980s when the Bell System held a monopoly over telephone service in the United States. This is a story about challenging the status quo when the status quo is wrong. At the time, businesses had no other choice for their telecommunications needs. Our founder, an entrepreneur, was frustrated by the situation, especially since Ma Bell’s service was so poor. So he set out to challenge them.

He filed an application with the Public Utilities Commission to build out a fiber-optic network in order to offer alternative telecommunications services to businesses. He was turned down. Not once, but several times. He was persistent, and after several more attempts, he was finally granted provisional rights to offer services in a select number of markets to a select number of businesses. Our company was born. Finally the phone company had competition.

Fast forward a few years to the early 1990s. The federal government passed legislation that leveled the playing field for companies like ours. This fueled enormous growth for us, but this growth soon became an Achilles heel. In trying to meet the demands of customers who wanted an alternative to the phone company, we found ourselves trying to service everyone that came to us and we became everything to everyone. To deliver services, we even ended up outsourcing some of our infrastructure back to the phone company. That’s right—we were relying on the company we’d set out to challenge. For a period of time, we lost our competitive edge. Our service suffered and we learned some valuable lessons.

In the early 2000s, we took stock of the situation and decided that in order to provide a real alternative to our customers, and in order to fulfill the founding mission of the company to deliver a real alternative to the phone company, we had to provide a 100 percent independent infrastructure. We invested several hundred million dollars to launch a network build-out and expanded our reach by 300 percent, reducing our dependence on the phone company to zero. We’ve come out on the other end, fulfilling our founder’s belief that there had to be a better way for companies to get telecommunications services. (See Laura’s storyboard in Figure 6.6.)

Figure 6.6 Laura’s Who I Represent Storyboard

Note: We will present two more examples of Who I Represent stories in Chapter 10 (from a company founder) and in Chapter 11 (from a manager).

The Right Tool for the Job Story

In addition to the three basic story types (Who I Am, Who I’ve Helped, Who I Represent), you might find yourself in need of other stories. It’s all a matter of figuring out the next point you need to make, the belief or idea your buyer must arrive at before proceeding up the ladder to the next rung in his or her buy cycle. In the following story, Adam Luff, a sales executive for a global enterprise IT company, identified the point he needed to make and built a story that was the right tool for the job.

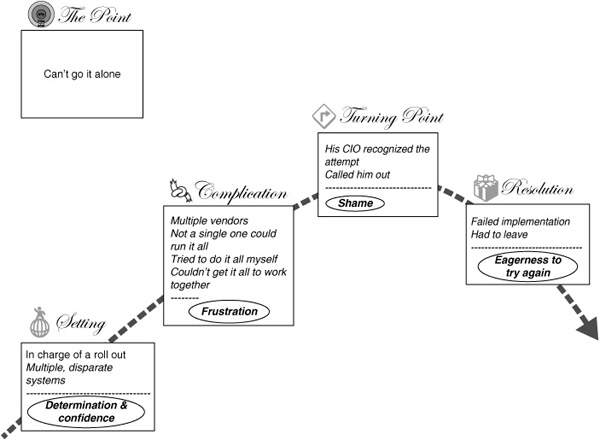

Adam’s Story About a week after I attended a Story Leaders workshop, I gave Ben a call.

“I need help with a story,” I said. “But I don’t even know which one to use. Can you give me a hand?”

Ben said he’d help, so I told him what my situation was and the point I wanted to make. “I have a call with two IT guys next week—our first meeting—but I don’t think my standard Who I Am story is right. And since they’ve done business with us before, I don’t think my Who I Represent story is right, either. I’m stuck.”

Then I got to the crux of the matter. “The thing is, these guys are cheap,” I said. “They’ve never spent any money on implementing our applications. They think they can do it all themselves, which is why they’ve failed three times. Since they already have egg on their faces, I have to tread carefully. I have to get them to realize that doing this project-on-the-cheap is false economy, without ticking them off.”

“So you want them to come clean,” Ben said. “You want them to admit that the source of their problem is that they keep trying to go it alone—and you want them to trust you enough to accept your help.”

“In that case,” Ben said, “I think you’re going to need to go first. Have you ever had a similar experience, a time you tried to ‘go it alone’ and it backfired?”

Now that Ben mentioned it, I had. In the late nineties, I’d been in the same position as those IT guys. I’d worked in an IT department and was put in change of a software implementation that required me to stitch together three different systems. I didn’t have any middleware tools, but I was full of guts and determination. Looking back, I guess I was a bit of a maverick, trying to impress everybody by doing it myself without spending any money. In those days, that’s how I thought you ran a business. I struggled with the project for about 18 months, practically pulling out my hair and getting more miserable all the while. After yet another meeting in which I’d had to tap-dance around the problem, the CIO took me aside. “Stop being a bloody Rambo,” he said, “and get yourself some help.” But by then it was too late. I knew he wasn’t going to sack me, but I also realized there was no way to save face after failing so badly for so long. So I left. (See Figure 6.7.)

“Sounds like a good story to me,” Ben said.

“But there’s no resolution,” I said.

“In this case,” Ben said, “I think that’s the point—that you weren’t able to resolve the situation, that you failed, that there was no resolution. You portray yourself as vulnerable and flawed. I think it’s the right tool for the job.”

The following week, when I showed up at the client’s office, the receptionist led me to the company cafeteria—not exactly an intimate setting for a meeting. The two IT guys were waiting for me. They seemed very defensive, sitting there with their arms crossed, probably expecting the standard chest-beating exercise we salespeople are known for. I started by asking if I could tell them a story. They got a kick out of that. One of them actually did a Wile E. Coyote cartoon double take.

“Sure,” he said. “Whatever.”

So I started in. When they realized I was telling my story, not a company story, they stopped being so standoffish and started paying attention. And sure enough, once I passed the torch, they opened up and told me why the previous implementations hadn’t gone so well—exactly what I’d been hoping to hear from them.

But then something happened that I hadn’t been expecting. One of the guys pulled out his phone, called a coworker, and asked him to meet us in a conference room. When he got there, the IT guy said, “Come meet with Adam. He’s not trying to sell us anything. He just wants to hear about what’s going on to see if he can help.” They eventually called in yet another colleague, and I spent the next two hours in that room, listening to their stories. By the time I was done, I had three real opportunities when all I’d hoped to do was break the ice with the original two guys.

The Curiosity Rung: Prospecting

Whether you’re making a cold call, making a warm call, or working the floor at a trade show, approaching strangers for the first time is always tough—probably the toughest part of being a salesperson. The success rate is low. Rejection is a given. It’s no wonder so many of us develop a case of “call reluctance.”

The key to success, of course, lies in piquing a prospect’s curiosity. But we have to be quick. We know we have only a brief window of opportunity—10 to 20 seconds—before a prospect says “tell me more” or “not interested.” A lot of salespeople use those few seconds to talk about what they do or how they do it. We believe that’s a mistake. Remember Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle from Chapter 5 (see Figure 5.2)? Sinek contends that we are most effective when we communicate from the inside out. The inside (the why) is a belief. If you have only a few seconds to make a buyer curious, start with the why of your story—the point (yellow card). Lead with a belief, not facts. Use those first few seconds to activate someone’s curiosity, which will earn you the right to tell the rest of the story.

Let’s say Ben is at a trade show cocktail reception with lots of potential prospects. He approaches the vice president of one such company and leads with the point (in italics) of his Who I’ve Helped story about Phil Godwin: “My name is Ben Zoldan with Story Leaders and although we’ve never met, I’d love to share a story with you about another senior sales executive I’ve worked with who believed in affecting real change; creating a real transformation throughout his organization.” (See the yellow card of the storyboard in Figure 6.5.)

The VP of sales can go one of two ways: he will either say, “Sure, tell me more,” or break eye contact and walk away. We have found that when we offer a story, very few people turn us down. And when we offer a story that is connected with a point (a why), we’ve found it increases the chances of piquing someone’s curiosity. When the VP says, “Sure,” Ben can then tell a two-minute version of his Who I’ve Helped story about Phil Godwin.

Leading with the why activates the receptive limbic brain, as opposed to leading with the what or how, which activates the left brain’s skeptical defense mechanisms. The outcome or resolution (red card) is the what of a story. If Ben had led with the resolution of his Phil Godwin story—“I helped Phil increase revenues by 30 percent”—he would have sounded like every other salesperson. Instead, by working from the inside out, leading with a belief, rather than a what, he connected with the VP’s limbic brain (the emotional brain), where curiosity resides—and earned a couple more minutes, enough time to tell the rest of the story, which includes the resolution— what happened.

Marketers know all about appealing to the limbic brain. Consider Apple’s popular and successful “Think different” ad campaign. The commercials don’t lead with facts: “An iPad will allow you to do x, y, and z!” Rather, they present viewers with images, music, and a simple belief (“Think different”) that make viewers feel good about Apple products and curious to learn more. As salespeople, we can do the same with our prospects if we lead with belief and emotion and save the facts for later.