CHAPTER 9

Shifting the Herd: The Enterprise Sale

Change does not happen from the top down, it happens from the bottom up.

—Barack Obama

How Enterprises Change

In Chapter 5, we explored why it’s so difficult to influence people to change: change is slow, and it requires struggle. Influencing enterprises to change is even more daunting. Instead of trying to overcome a single person’s natural resistance to try a new way, we’re challenging the status quo of a large organization made up of an untold number of individuals, in a variety of silos, most of whom we don’t even have direct access to.

In Solution Selling and CustomerCentric Selling, we taught sellers “California selling”: “Call high, stay high.” A key element of our qualification model was “getting access to a power sponsor” or “decision-making-level” person, someone within an organization who has “budget,” the means and authority to spend. We believed that in order to sell big to an enterprise, the seller needed to get in near the top. Since then, we’ve learned there is a lot more to it.

Mike’s Story: Keith’s One Guy (Part One)

Back in my Solution Selling and CustomerCentric Selling days, I had dozens of affiliates selling my sales methodology. Of those, one affiliate brought in more revenue than all the others combined.

Keith was the very best at both selling and teaching our methodology. At the time, I didn’t really get why he was so much better than everyone else in our organization at selling to large enterprises. Looking back, of course, I recognize that he was a masterful storyteller and story tender, but there was something else in his approach to the enterprise sales cycle that set him apart.

This was the early 1990s. Solution Selling was starting to take off, but mostly with small-to-medium-sized businesses. With release of my book Solution Selling in 1993, I was able to call into larger enterprises. One day, I got the contact number for IBM’s president of North American operations, and I cold-called him. It began as a promising call; I got him on the line and we had a conversation. However, I was quickly relegated to the black hole of the IBM training department. I’d done exactly what I taught—called high, to the C suite—but my conversation with the prospect had nevertheless led down a rabbit hole to nowhere.

A year later, I got a call from Keith explaining that he had an “in” with a small IBM business unit. His champion was a midlevel sales director who wanted us to do a workshop for his group. At the time, the status quo at IBM amounted to little more than sales training by subject: negotiation, proposal writing, presentation skills, handling objections, and so on. This one sales director believed Solution Selling represented a new way.

I was skeptical that this one person, this one workshop, would turn into a larger opportunity. I remembered asking Keith, “Do you have access to power?” Keith told me no, but he felt comfortable expending his efforts on this midlevel sales director. In my cold call the year before, I’d gotten to the executive who ran all of North America for IBM, several levels higher than the one Keith had access to, and it had gotten us nowhere. Of course, I gave Keith the green light, but I didn’t have much faith that it would go beyond a single departmental workshop; Keith’s “in” was simply too low.

Boy, was I wrong! After that first workshop, Keith’s one guy not only introduced Keith to every one of his peers but he also sold for him. And the attendees of the workshop told their peers about Solution Selling, who then told their peers. A movement of believers coalesced, and those believers became internal sellers for Keith, almost as if they were the sales reps and Keith were the sales manager. Within three months, his single workshop with his “one guy” had turned into a half-dozen workshops.

Why did Solution Selling take off at IBM? At the time, the company didn’t have a formal, structured sales process, and those managers and reps who were exposed to Solution Selling saw it as a new way, a departure from the status quo. The groups that went through our workshops became “tribes” that then spread to message to other tribes, eventually forming a virtual movement within the organization that multiplied exponentially. Before long, I was getting bigger and bigger royalty checks from Keith.

Tribes

In his book Tribes: We Need You to Lead Us, bestselling author Seth Godin defines a tribe as any group of people, large or small, who are connected to one another, a leader, and an idea. As human social units, tribes are naturally occurring groups. We’re all members of tribes—both in our personal lives and at work. We form tribes inside of companies. It’s what we do; it’s what we’ve always done.

“Each tribe has a tribal leader,” writes Godin, “connecting people with ideas.”

Tribal leaders find others who share their belief, or they influence others to believe what they believe or value. Tribal leaders assemble tribes that assemble other tribes. That’s how an idea can become a movement.

It’s a phenomenon familiar to sociologists and anthropologists. Researchers have studied large herds of animals to better understand how change happens in the wild. The conventional wisdom had always held that pack leaders were responsible for a herd’s shifts and direction changes. Researchers have repeatedly observed that this is not the case. Herd movement turns out to be less top-down—more democratic—than people previously believed. Any single animal within a herd can start a shift in the herd’s direction. All it takes is one animal who senses a need, such as the threat of a predator, and moves away from it. Then a few others follow, forming a subgroup (a tribe). Then other subgroups form and make the move, until the subgroups make up 51 percent of the herd. Fifty-one percent is the tipping point at which the whole herd then moves together.

In observing this phenomenon, researchers have proven that it’s not necessarily pack leaders who influence change; it can be any one animal within the herd. In fact, the pack leader is among the least likely to influence change, because the pack leader is generally buffered and surrounded, insulated in such a way that he can’t sense the need for change. If the herd were to rely only on the pack leader, it would fail to make necessary moves and changes.

Such was the case with IBM. From his insulated position high up within the enterprise, the senior executive I originally spoke with didn’t see a need for change. It wasn’t until Keith succeeded in influencing a tribal leader who then went on to influence other tribes that our message spread and eventually worked its way up. Once that happened, it was little surprise that Solution Selling met with favor at the C level. Senior executives love consensus, and a grassroots movement of tribes fits the bill.

Modern psychological and economic researchers have observed that humans naturally prefer democracy (e.g., 51 percent rules) as opposed to top-down leadership or government by the few (e.g., oligarchy). As members of subgroups (tribes) that make up larger groups (herds), we are all wired to move with the herd.

Herd behavior accounts for how humans in a group can act together organically, without planned direction. Mirror neurons—triggering our natural inclination to reflect the emotions of others—facilitate this process. Herd behavior can be observed during stock market bubbles and crashes and street demonstrations; at sporting events and religious gatherings; during episodes of mob violence; and even in everyday decision making, judgment, and opinion forming.

Consider the case of how enterprises adopted Microsoft Office. Microsoft developed Office for individual home PC users. But when secretaries and others started bringing Office to the office, installing it on their work computers, a grassroots movement arose. No marketing was involved, just word of mouth, tribe to tribe to tribe. Today, Microsoft Office enjoys more than 90 percent market share among enterprise users.

Other “benign” herd behaviors occur in everyday situations where people make decisions based on the decisions or behavior of others. Suppose you and your spouse are walking down the street in search of a place to eat dinner. Restaurants A and B both look appealing—it’s a toss-up— but they’re both empty because it’s early in the evening. You randomly choose restaurant A. Soon another hungry couple walks down the same street. The two restaurants look about the same to them, too, but when they see that restaurant A has customers, they choose A. As the same thing happens with more passersby, restaurant A ends up doing more business that night than B. This phenomenon is referred to as an “information cascade.”

The Tipping Point

“The tipping point is that magic moment when an idea, trend, or social behavior crosses a threshold, tips, and spreads like wildfire,” writes Malcolm Gladwell in his book The Tipping Point. He observes that change often occurs quickly and counterintuitively and that “little differences” can sometimes impact big changes. As with epidemics, the success or failure of corporate endeavors can spread or die in unpredictable ways, depending on whether the tipping point is reached. Gladwell defines a tipping point as “the moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point.”

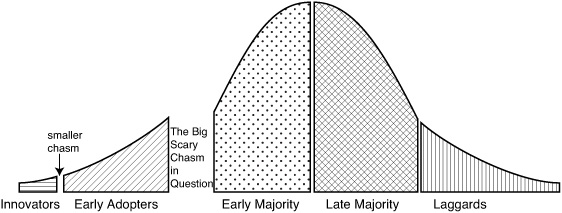

In his 1991 book Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey Moore identifies not one tipping point but two critical points—two “chasms”—that determine whether a change will take place in a market. Moore’s model follows the basic law of diffusion of innovation, which when visually represented, looks like a bell curve. Figure 9.1 is based on Moore’s model.

Figure 9.1 A Model of How Change Occurs in a Market

Moore’s model includes five distinct groups:

Innovators (4 percent)

Early adopters (16 percent)

Early majority (33 percent)

Late majority (33 percent)

Laggards (14 percent)

While Moore’s model pertains specifically to markets, individuals in organizations adopt new ideas in a similar fashion. There are always a few people—tribal leaders— who are willing to challenge the status quo within an enterprise. These tribal leaders are like innovators and early adopters within a market. If a tribal leader is successful at bridging the two chasms and then convincing enough people to follow her lead, her movement can reach the tipping point and influence change throughout the whole organization.

Story Leader to Tribal Leader to Tribe

Based on our new understanding of how change occurs within enterprises, we now advise our workshop participants not just to focus on the so-called decision maker but also to find the tribal leaders—the people within an enterprise who (1) are willing to hear your story, (2) believe the status quo is worth changing, and (3) demonstrate a willingness and ability to share that belief with other tribes, to say, “Follow me.” The more disruptive (non–status quo) your idea, product, or service, the more resistance you’ll get from the majority; a good idea, however, will eventually find its way to the majority and to the so-called decision makers.

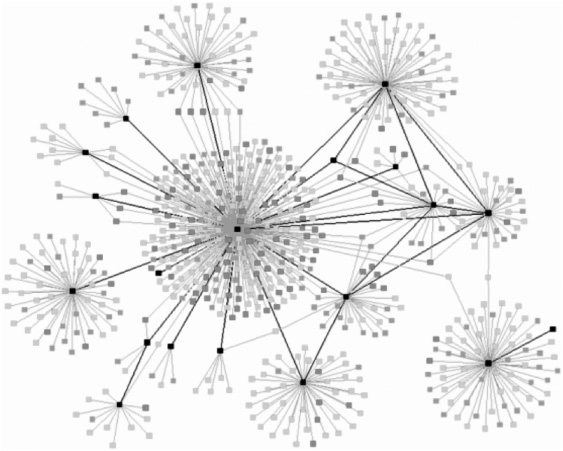

Every large organization, enterprise, and social group is made up of smaller tribes. These tribes form around common beliefs, ideas, and values. All tribes have a tribal leader—the individual who believes in connecting his or her tribe with other tribes. Tribal leaders reveal themselves when they begin to connect openly with others. When you successfully influence a tribal leader, it’s like dropping a stone into a pond, creating ever-widening ripples on the water; your influence spreads exponentially. Of course, the pattern of spread within an enterprise isn’t as predictable as concentric circles. It might look more like a web or network of webs (see Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2 How Change Spreads Within an Enterprise

The point is that it takes only one salesperson who influences one tribal leader to start the spread of an idea. In this way, one salesperson can move an entire enterprise.

Mike’s Story: Keith’s One Guy (Part Two)

Keith didn’t have to “start high.” All he had to do was start with one tribal leader, who then gave rise to more tribes. Eventually, one of those tribes included a C-level executive—the same one I had contacted the year before—who had the ability to affect a much larger tribe, which in turn led to the tipping point at which IBM moved as a herd. Then the enterprise sale was made.

In Keith’s case, he ended up with a multimillion-dollar sale. IBM purchased the licensing to Solution Selling, which it then privately branded as its own Signature Selling model and used to train more than 15,000 IBM salespeople. To this day, when I’m at an IBM office, there are still people who ask me to autograph their copy of Solution Selling.

Keith went on to make other large enterprise sales by intuitively understanding tribal and herd behavior. It wasn’t that he thought selling high was ineffective. He knew it was a way, just not the only way. He didn’t worry about influencing the person with “budget” but focused instead on finding a “VP of change”—a person who knew how to advance an idea within his or her enterprise.

Help Your Tribal Leader Become a Story Leader

We believe the most powerful tool to influence a tribal leader is stories. Stories are the most effective means by which we communicate our values and beliefs and influence others to believe what we believe, and beliefs and values are what connect tribes. Stories can provide the vehicle by which ideas can be spread from tribe to tribe, leading to movements. Even if you succeed in making contact at the C level, the executive won’t necessarily perceive a need for change unless those around her seek to change the status quo. So don’t get focused solely on access to the person with “budget.” Ask yourself, Is she in the tribe? Is she a tribal leader? Think of yourself as a “story leader” who focuses on starting a grassroots internal movement by getting a tribal leader and his or her tribe of similarly minded people excited about a new idea, belief, or message.

In fact, when a seller overtly seeks, through a lower-level executive, access to the decision maker or the person who signs off on deals, the seller risks demotivating the lower-level executive from becoming a tribal leader. If I’m just a stepping stone for this guy, the lower-level exec thinks to himself, why should I bother being his champion? We can only imagine how many deals salespeople have lost over the years because of our poor understanding of how change actually occurs in an enterprise.

Ultimately, the level in the enterprise at which you need to connect depends on several variables—for example, the size of the potential transaction, the level of disruption your offering poses to the organization, and the number of people affected. And, yes, buy-in from a C-level executive can be a requirement for some sales; however, the C-level executive is just one person. Keep in mind that the C-level executive is more likely to move once the organization around her has already sensed the need to change. If that’s the case, it’s likely tribes are already connected to the new idea and are in discussions with other potential vendors.

Helping Your “One” Become a Tribal Leader

Create the ripples, starting with one person who’s willing to listen to your story and wants to challenge the status quo. Then empower that person to tell his or her own story within the tribe. In order to do this, tend to and document your prospect’s story.

Imagine you’ve just had an ideal sales call. You totally connected with your prospect. Now you need that person to become a tribal leader and start selling for you. But how can you teach a prospect to tell her story in a 45-minute sales call? The answer is, you can’t. After all, you’ve probably been perfecting your own story for weeks or even months. The question, then, is what can you do?

First, make sure you have a powerful story. A story that moves a listener emotionally is more likely to be remembered and retold—and more likely to be internalized and adopted by your prospect.

Second, close your call by telling your prospect that you’d like to send her an e-mail summing up your conversation in order to make sure you “got” who she is and that you’re both on the same page.

Third, help your tribal leader effectively build her own story by documenting it in an e-mail. As mentioned in Chapter 8, reflection is an essential part of story tending, as it ensures that the listener “gets” the whole story accurately and completely. Be sure that the story includes all the essential elements mentioned in Chapter 5:

![]() Point. Your prospect’s belief, mission, or goal around which the tribe will form.

Point. Your prospect’s belief, mission, or goal around which the tribe will form.

![]() Setting. How your prospect’s journey started, the character(s), and the emotions.

Setting. How your prospect’s journey started, the character(s), and the emotions.

![]() Complication. Your prospect’s challenges and pains along the way, including the impact of those pains and the emotions involved.

Complication. Your prospect’s challenges and pains along the way, including the impact of those pains and the emotions involved.

![]() Turning point. Focus on the timing. Why take action now?

Turning point. Focus on the timing. Why take action now?

![]() Resolution. The resolution to your prospect’s story takes place in the future, when the enterprise will use your offering to address its challenges.

Resolution. The resolution to your prospect’s story takes place in the future, when the enterprise will use your offering to address its challenges.

Here is an example of how to document a prospect’s story after a call with a vice president of sales.

From: Ben Zoldan <[email protected]>

Sent: Weds, 19 May 2010 03:00:24

To: Beth <[email protected]>

Subject: Discussion Summary

Dear Beth,

It was great talking with you today. Thanks for sharing with me your beliefs, the challenges you’re facing, and your goals. I’m writing because I want to make sure I fully understand your story. I’d like to start with a recap of our conversation.

![]()

As with many sales managers, you told me you find yourself in a situation where the majority of your sales are being generated by a select few salespeople. You indicated that you believe the bottom 80 percent of your salespeople, given the proper training and tools, are capable of doing much better, and that their improved performance will have a significant impact on your company’s success.

![]()

Your belief in the potential of your salespeople is based on experience. After fifteen years in sales—starting as a frontline salesperson and culminating with your elevation to sales manager six years ago—you recognize that the members of your sales force have the expertise, intelligence, dedication, and drive necessary to succeed.

![]()

What’s missing is something else. As we talked about your best salespeople—the three who accounted for almost 90 percent of your sales last year—you said that what sets them apart is the rare ability to connect, on a human level, with their customers, generating trust and enthusiasm. On the contrary, the rest of your salespeople have weaker interpersonal skills. “As smart as they are,” you said, “they have a tough time connecting.”

Up until now, executives in your organization weren’t particularly concerned about the distribution of sales so long as the department was meeting its goals. Recently, however, they’ve acknowledged that the situation puts the company at risk. The loss of a single top seller could wreck your numbers. Not only are they now eager to address the issue, but they’d like to do so before the end of the year.

![]()

In discussing possible solutions, we talked about the fact that what the best sellers do—connecting with people—isn’t an innate ability that you either have or you don’t. On the contrary, given proper models and training, it’s something all salespeople can learn to do— to connect through stories, to listen empathetically. We also talked about the value of building a culture around the stories of a company.

You suggested we get together to further discuss the Story Leaders approach. Before we schedule a meeting, would you mind letting me know if I understand your situation?

I’m looking forward to continuing our conversation.

Sincerely,

Ben

We’ve found that such an e-mail is of great value in an enterprise sales cycle for several reasons:

![]() It reflects the story in a way that ensures that you “got” the prospect; if you didn’t, the prospect can easily reply with revisions, editing the story.

It reflects the story in a way that ensures that you “got” the prospect; if you didn’t, the prospect can easily reply with revisions, editing the story.

![]() It provides your prospect with a written version of the story; you are essentially coaching that person in how to tell the story.

It provides your prospect with a written version of the story; you are essentially coaching that person in how to tell the story.

![]() An e-mail is easily forwarded to other potential tribe members, who in turn are better able to tell the story themselves if they have it in writing for reference. This has proven to be the number-one use of e-mail in the sales cycle. Good letters that tell a story get forwarded, especially upstairs to higher-level tribes. An e-mail provides a safe way for a tribal leader to communicate to a higher-level tribal leader and creates the ripple effect.

An e-mail is easily forwarded to other potential tribe members, who in turn are better able to tell the story themselves if they have it in writing for reference. This has proven to be the number-one use of e-mail in the sales cycle. Good letters that tell a story get forwarded, especially upstairs to higher-level tribes. An e-mail provides a safe way for a tribal leader to communicate to a higher-level tribal leader and creates the ripple effect.

![]() Writing the story yourself gives you the opportunity to anticipate and address questions or concerns that other tribal leaders may have about your offering. They can edit the letter and/or ask for clarification in writing.

Writing the story yourself gives you the opportunity to anticipate and address questions or concerns that other tribal leaders may have about your offering. They can edit the letter and/or ask for clarification in writing.

![]() An e-mail can be used for internal documentation inside your organization—for management to qualify for use of resources, for facilitating co-selling by support staff, for application engineers to demonstrate or “present” the product at a later date, and so on.

An e-mail can be used for internal documentation inside your organization—for management to qualify for use of resources, for facilitating co-selling by support staff, for application engineers to demonstrate or “present” the product at a later date, and so on.

![]() As an e-mail circulates, it can also facilitate spread by word of mouth.

As an e-mail circulates, it can also facilitate spread by word of mouth.

Connected or Unconnected?

Your prospect’s reply to your e-mail message will help give you a sense of his or her level of enthusiasm for your offering and a sense of how strongly the two of you connected, a critical first step in the seller-buyer relationship. Consider two possible responses to the previous letter.

------ Forwarded Message

From: Beth <[email protected]>

Sent: Thurs, 20 May 2010 01:00:54

To: Ben Zoldan <[email protected]>

Subject: RE: Discussion Summary

Ben,

Thanks for the call. We will review your material when time permits. At this point, I cannot attend one of your workshops.

Thank you again for your time and the information.

Best regards,

Beth

Response 2

------ Forwarded Message

From: Beth <[email protected]>

Sent: Thurs, 20 May 2010 01:00:54

To: Ben Zoldan <[email protected]>

Subject: RE: Discussion Summary

Hi Ben,

I would love to learn more about your approach and further discuss. Your summary is right on the money—I agree about the power of story as a way to communicate. I once heard that people remember stories 10 times more than they do facts or statistics. I am a big believer in sharing stories as a way to connect with people. It’s what I’ve always known to do. What are you thinking is next?

Beth

Note not only the difference in content but also the difference in tone. The word choice in response 1 is polite but formal—a standard reply—whereas the word choice in response 2 (“I would love to learn more. . . . I am a big believer. . . .”) conveys real emotional connectedness with the seller and offering. If you were Ben’s sales manager, which opportunity would you want to invest company resources in?

Consider the story ladder for a complex B2B sale, a “committee” sale in which your solution or offering will impact multiple silos—for example, engineering, production, operations, finance, order processing, sales, marketing—within your prospect’s organization. Each silo is a tribe. As an insider, your tribe leader will know far more than you ever could about the internal politics and personal agendas at play within the enterprise. Your tribal leader will also be in a much better position to identify other tribal leaders who might embrace your story.

The more complex the organizational decision-making process, the more important it will be for you to follow “interdepartmental bread crumbs” when you are tending your tribal leader’s story. If you know your tribal leader will have to get other silos on board, build into your reflected story complications and benefits that pertain to other silos. Give the story the broadest possible appeal. And remember: stories are our most powerful way to create movements and motivate prospects to influence change within their organizations. Find your tribal leaders and help them lead change.