CHAPTER 11

Continuing the Journey

The closer psychologists look at the careers of the gifted, the smaller the role innate talent seems to play and the bigger the role preparation seems to play.

—Malcolm Gladwell, Outliers: The Story of Success

Part One: Trying It

Give this a try: Set down this book and put your hands together, interlocking your fingers. Now look at your hands. Which thumb is on top? Now put your other thumb on top. Feels all wrong, right? That’s because you’ve been doing it the other way your whole life. Trying anything new takes us out of our comfort zone.

This chapter is going to help you try the new things you’ve learned in this book. They might be uncomfortable at first. Expect to struggle. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes.

Ben’s Story: John Burke’s Guilt

John Burke is the group vice president of Oracle’s applications business unit. The first time I ever talked to John was when I cold-called him. We had a pretty good conversation, during which he shared his frustration with the 80/20 rule.

“At Oracle,” he said, “It’s more like 90/10.”

As part of his evaluation of Story Leaders, he wanted to preview the model and agreed to attend one of our public workshops in Del Mar, California. But he had one condition: “If I come out to Del Mar, take me golfing.”

“Sure,” I said. “We’ll play golf.”

Later, I learned that John is an avid horse racing fan, too. I didn’t realize that the area’s great golf courses—and Del Mar’s racetrack—were probably the main reasons he agreed to come at all.

The workshop lasted two-and-a-half days, so I scheduled a tee time at nearby La Costa Resort for the afternoon of the third day. I’d been monitoring John for his buy-in during the workshop, but I decided that asking him about it over golf would be too salesy. By the sixteenth hole, though, I couldn’t help myself.

“So, what do you think, John? Do you see Story Leaders helping?”

John was brutally honest. “I get it, I really do,” he said. “But I don’t know if Oracle is ready for it. It’s different than what we do, and quite frankly, it feels a little weird. Plus the name, Story Leaders—that’s weird, too. Probably too weird for us.”

I thought about all the time I had spent with him and the money I’d just spent on the round of golf and proceeded to hit my next ball into a water hazard. I didn’t regain my composure until we got to the last hole.

“How about this?” I said. “I know it feels weird now, but since I took you golfing, do me a favor. On your next sales call, try everything you learned in the workshop. Start with, ‘Can I tell you a story?’ End by passing the torch. And play back what the prospect tells you. Tend his story.”

I knew I was playing on John’s guilt, but I didn’t see another way.

“Okay,” he said. “I promise I’ll do it on my next sales call.”

The following Tuesday, I got a call from John. “My story wasn’t very good,” he said, “but it worked.”

He told me that he and another Oracle executive had just come back from a sales call with the CIO of a Fortune 100 company. Before the meeting, in their prep conversation, John had told his colleague that he wanted to open the sales call with a story—his Who I Represent story from the workshop. But his colleague wasn’t comfortable with the story, especially revealing the company’s dumbass moment.

“John, you can’t say that to a customer,” he said. “We don’t air our dirty laundry like that.”

That only gave John even more incentive to tell the story during the meeting.

“So I started the sales call with the story,” John told me on the phone. “The CIO said, ‘Thanks, I never hear anything like that from vendors.’ And then he tells me his story, which included his dumbass moments. It was like a role-play straight from the workshop.”

But there was more: “As soon as the meeting was over and we got back into the car, my once-skeptical colleague turns to me and says, ‘Tell me that story again. I want to use it.’”

Even though it felt weird for John, using what he’d learned in the workshop and getting real-life feedback from a buyer was the turning point for him. He has since put his whole team through the Story Leaders workshops.

“We’ve been trained our whole careers to ask diagnostic questions, to deliver value props, to do ROIs. We expect people to respond to all this left-brain stuff, and it usually doesn’t work. It turns people off,” John says. “Connecting with someone’s emotional brain through honest, authentic stories, combined with real listening, is a better way. All the best salespeople I’ve ever known and all the best sales calls I’ve ever been on prove this to be true.”

The point of the story is, take a chance. Tell your stories. They don’t need to be perfect. It will feel weird at first, but don’t be afraid to try a new way.

John Burke’s Story: Who I Represent

In 2005, when Oracle bought PeopleSoft, we told the world we would “fuse” the two systems, bringing together the best features of both Oracle EBS and PeopleSoft’s products. We would call the new system “Fusion.”

Right away, an interesting thing happened. Sales slowed down for both product lines. Basically our customers told us, “Look, we’ve invested a lot to run our business on either PeopleSoft or Oracle EBS. We need you to continue to support our product line.”

At first we didn’t get it. Our strategy was to take the best from each system and create something better. But we missed something that was critical to our customers at the time. They already had major investments in the systems they had been running, and creating something new would disrupt their environments. Fusing the systems together to make something new and “better” could actually cause problems. That was our dumbass moment: thinking we knew what was best for our customers instead of letting them tell us.

Fortunately, our customers spoke loud and clear: “If you want to build a new product, we suggest you focus on what has changed and build that rather than your previous idea of merging two systems together.”

We listened. Although we thought we were doing the right thing after the merger, within five months of the acquisition, we changed our strategy and announced “Applications Unlimited.” Because our customers needed us to support whichever system they had been running, we guaranteed we would continue to build new capabilities for each existing product for five years and that we would provide lifetime support for both systems. As long as a customer wanted to use a product, we would support it.

Our customers were a little skeptical at first, but we delivered with the new releases of PeopleSoft, EBS, and other products. Once we proved we were executing on our commitment, our customers began to do more with us.

Specifically, our customers wanted three things. First, they said they were ready for the cloud, and they wanted software designed to run either in the cloud, in their data centers, or both. Second, they wanted embedded business intelligence, a system that automatically delivered reports and allowed them to view the data however they wanted without having to move it to a warehouse. Third, they wanted built-in collaboration—a way to collaborate among employees, customers, suppliers, and partners built right into the transaction flow of the system.

So those became the driving tenets of our Fusion Applications project.

The point is, we got our original strategy and communication all wrong, but we listened to our customers, and we changed. It has taught us a major lesson in how we listen to our clients, especially during and after acquisitions.

Mike’s Story: The Learning Zone

In the late 1980s, a career trainer friend of mine said, “Mike, I have a gift for you, trainer to trainer.”

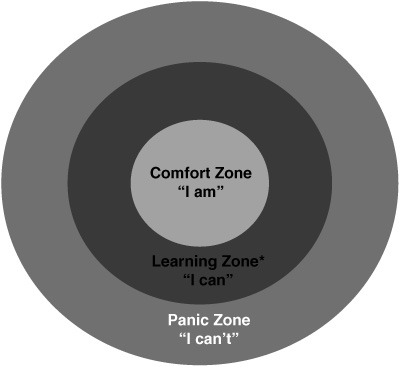

His gift was a diagram of the “learning zone” (see Figure 11.1). He drew three concentric circles on the whiteboard. The middle circle, the “bull’s-eye,” was the comfort zone, the “I am” zone. The next circle was the learning zone, the “I can” zone. The outer ring was the panic zone, the “I can’t” zone.

Today, we share the learning-zone diagram with workshop attendees to help them visualize the idea of change. We then ask them to name the kinds of lessons they’ve taken. We get answers such as golf lessons, scuba-diving lessons, skydiving lessons, piano lessons, and French lessons. Then we ask how comfortable they were the first time they swung a golf club, breathed underwater, jumped out of an airplane, played a scale, or ordered a meal in French. The answer is always the same: “very uncomfortable.”

That discomfort is a natural part of learning a new skill. In order to get comfortable doing anything new, you must leave your comfort zone and have the courage to venture into your learning zone.

Part Two: Practice

Mike’s Story: Freedom

High school was a difficult time for me. I was small, skinny, and poor. There was no such thing as an allowance in our house. Worse, I had a violent, alcoholic father. From the age of 14 on, I worked seven days a week stocking a retail liquor store. I was saving for a car. To me, driving meant freedom. The day I turned 15 and a half, I was the first person in line at the DMV with my mother to get my learner’s permit.

I bought a car that didn’t run. My grandfather was a GM mechanic. He patiently showed me how to do everything the car needed. We put in a new clutch, cleaned the carburetor, replaced the points and plugs—the whole deal.

For the six months between getting my learner’s permit and taking my driving test, my biggest obstacle was learning to drive a stick shift well enough to start on a hill and parallel park. Talk about something nonintuitive! I was amazed by experienced drivers who effortlessly coordinated the gas, clutch, and gearshift. They could even drive while they were talking and eating. How did they do it?

On my sixteenth birthday, February 1, 1963, in the pouring rain, I was back in line at the DMV with my mother to take the test for my driver’s license. Unfortunately, I still hadn’t gotten the hang of driving a stick. I had to think through every move I made. It was all very left-brain. During the test, I was concentrating so hard that I failed to hear the fire engine behind me and didn’t pull over as I was supposed to. I was mortified, not to mention devastated to think I wasn’t going to get my license.

But the DMV examiner took pity on me. Perhaps it was my vulnerability.

“Let’s continue,” he said.

I nailed the parallel parking, and he passed me. I was getting my driver’s license after all. Freedom! It’s still one of the biggest days of my life.

Weeks later, I was driving home from my job at the liquor store when I realized I wasn’t even thinking about the clutch and gas and gearshift. Driving a stick had become routine. It was all a matter of practice, putting in enough hours.

Letting the Right Brain In

When it comes to learning a new skill, the procedural left brain is in charge. It’s focused on the mental bulleted list of tasks that need to be completed to execute the job at hand. In Mike’s case, he wasn’t able to hear the fire truck because he was concentrating so hard on the mechanics of manipulating the clutch, gas, and gearshift.

But eventually, even activities that are daunting at first— such as driving a stick—become routine. Eventually, we’re able to listen to music, have a conversation with a passenger, maintain a broader awareness of road and traffic conditions. It’s all a matter of putting in enough practice for the left brain to get the skill down and make it second nature. Only then, once a new skill becomes old hat, can the left brain relinquish some control and let the right brain engage more fully in the activity.

That’s the point you’re aiming for with your stories. Once you’ve practiced enough, you won’t have to consciously think about the card system, or emoting, or passing the torch. It will all come naturally, allowing you to be fully present with your whole brain instead of self-consciously worrying about each step along the way.

What Happens After You Read This Book?

In Outliers: The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell examines what makes high achievers different. His conclusion? Practice. About 10,000 hours worth, to be specific.

Here’s Gladwell in a Reader’s Digest interview:

An innate gift and a certain amount of intelligence are important, but what really pays is ordinary experience. Bill Gates is successful largely because he had the good fortune to attend a school that gave him the opportunity to spend an enormous amount of time programming computers—more than 10,000 hours, in fact, before he ever started his own company. He was also born at a time when that experience was extremely rare, which set him apart. The Beatles had a musical gift, but what made them the Beatles was a random invitation to play in Hamburg, Germany, where they performed live as much as five hours a night, seven days a week. That early opportunity for practice made them shine. Talented? Absolutely. But they also simply put in more hours than anyone else.

So how does a kid become the next Bill Gates or Tiger Woods? Gladwell goes on to say that people who become high achievers usually have parents who allow their children to concentrate on and spend extraordinary amounts of time on the activity that makes them happiest and in which they excel. Gladwell suggests that the amount of time high achievers need to invest appears to be 10,000 hours.

Exercises

Fortunately, because human beings are wired to think and learn in story, you won’t need to practice 10,000 hours of storytelling in order to influence change in buyers. But you’ll still need to practice a lot.

We offer the following exercises to help you develop the skills covered in the preceding chapters:

1. Build your story ladder.

2. Build your Who I Am story.

3. Build your Who I Represent story.

4. Build your Who I’ve Helped story.

5. Tend a story.

6. Story sharing.

7. Identify a stalled opportunity in your pipeline, and build a story to unstall it.

8. Share your stories with others: www.storyleaders.com/shareyourstory

The exercises are presented in the same order we use them in the workshop, which is itself the basis for the structure of this book. Feel free to skip around as needed.

Quick Story-Building Guide Several of the exercises will prompt you to build stories. In the following paragraphs you’ll find a quick refresher on story building.

Before you get started, go to www.storyleaders.com/downloads to download templates. We recommend you keep the storyboard template in front of you while you work, to keep on track.

You should also purchase three-by-five-inch colored index cards at your local office supply or stationery store. You’ll need five colors: white, yellow, red, blue, and green. Remember, you should be writing bullet points and keywords on your cards, not complete sentences. Writing complete sentences will activate your left-brain language center and interfere with your right-brain “multichannel” brainstorming. The storyboard is intended to help you organize your ideas. Think of your cards as prompts, not scripts.

1. The yellow card (your point). Start by figuring out the point you want to make.

2. The red card (resolution). Next, identify the end of your story.

3. The green card (setting). Working backwards, decide where your story should start. How did the journey begin?

4. The white card (complication). Now that you have the pillars of your story in place (point, resolution, and setting), it’s time to describe the struggle, the bumps in the road, the dumbass moments.

5. The blue card (turning point). How did things change? Was there an aha moment?

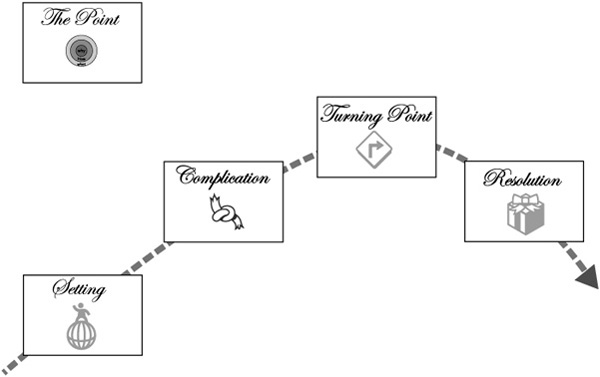

You now have the elements of a story that follows the arc of change (see Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 The Elements of Your Story Follow an Arc of Change

6. Emotions. On each card (excluding the yellow card), write at least one word that captures the emotion associated with that part of the story. Circle the word(s).

7. Tell the story. Use your cards for reference. Start by practicing in front of a mirror; then try it out on someone other than a client. At first, focus on what happened. Once you’ve got the sequence of events down pat, concentrate on the circled emotion words at the bottom of each card and emote them using nonverbal cues. Don’t try to tell the story from memory, without the cards, until it feels like second nature.

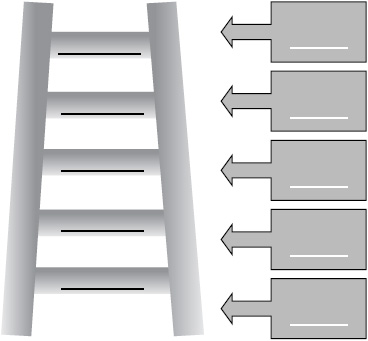

Exercise 1: Build Your Story Ladder Create a story ladder for your customers’ buy cycle. Start with a blank story ladder like the one in Figure 11.3. Next, make a list of the steps that your customers go through in their buy cycle. Condense the list into sales stages, and compare it to your current sales process. If they’re out of sync, now is a good time to adjust. The stages will be your rungs. Add them to your ladder, starting with the bottom rung and working up to the top rung—your buyer’s yes. Now, on the right side of the ladder, indicate which story you’ll use for each rung (i.e., the story that will make the point needed to move your buyer up to the next rung).

Figure 11.3 Blank Story Ladder

Exercise 2: Build Your Who I Am Story Your Who I Am story chronicles your professional journey. You’re the main character. The point (yellow card) is why you do what you do. The resolution (red card) is your current professional position. Once you identify your point and resolution, chances are that a natural beginning—how your journey began (green card)—will present itself to you. The complications (white card) detail your struggle, bumps in the road, and dumbass moments. The turning point (blue card) chronicles the transformation (possibly an aha moment) when you decided to become who you are today. What led you to change direction or alter your behavior?

A good Who I Am story inevitably shows vulnerability. It requires self-reflection and, often, an admission that there was once a time you weren’t as qualified, committed, or capable as you are today.

Exercise 3: Build Your Who (or What) I Represent Story If you work for a company, your Who I Represent story is the company’s story. If you’re self-employed, your Who I Am and Who I Represent stories are one in the same.

In the story of your company’s journey, the main character might be the founder or CEO. If you work for a big company with a broad range of product offerings, consider focusing your story on your particular business unit or product. For instance, instead of building a story about your employer, XYZ Company, which offers thousands of products, focus on the ABC product group you represent. Just as every person has more than one story, so does every company. Resist the urge to try to give a comprehensive company history. Instead, build a manageable story that conveys the point you want to make. That’s what John Burke did in his Who I Represent story, presented earlier in this chapter. Instead of trying to tell the whole Oracle story, he focused on a chapter in the company’s history that conveyed the point he wanted to make about the importance of listening to your customers and being willing to change.

The point (yellow card) of your Who I Represent story is to show why your company does what it does, including any guiding beliefs or values. The conclusion (red card) is what the company does today. The beginning (green card) is how the journey began. The complications (white card) include challenges the company faced, missteps, and dumbass moments. To keep a human face on the story, focus on the complications via the main character’s point of view. The turning point (blue card) is the moment at which the company turned itself around or took a new direction that led to what the company does today.

Exercise 4: Build Your Who I’ve Helped Story You’ll want to have at least one Who I’ve Helped story in your repertoire and probably more. Your customers and clients are the main characters in these stories, which are not about their companies but about their particular, personal journeys and transformations— ideally, transformations that occur because of your offering, product, service, or support. You might be a character in these stories too, perhaps coming onto the scene at the turning point. Your customers and clients can help you build these stories.

The point (yellow card) of a Who I’ve Helped story is your client’s belief—possibly a belief you influenced. The resolution (red card) is what your client is able to do today because of your product or offering. The beginning (green card) is how your client’s journey started. Take time to develop your client as a character; a listener will care more about a character who seems like a real person. The complication (white card) details your client’s struggles when he did things the “old way.” The turning point (blue card) is the aha moment when he started doing things the new way—with your help.

If you’re fortunate enough to build the story with your client’s input, ask him for at least one word that represents the emotion he felt during each part of the story, then write and circle those words on your index cards. When you practice the story, start by telling it to the client, who can correct any mistakes and help you flesh out the narrative.

Exercise 5: Tend to a Personal Story The goal of this exercise is to make another person feel “felt” using empathetic listening skills: awareness, encouragement, and reflection.

Begin by telling a friend, family member, or close colleague a story about your day, then pass the torch with some variation of “enough about my day; how was yours?”

Once your friend starts talking, give her your undivided attention. Use both nonverbal encouragement (voicing “hmm,” maintaining eye contact, leaning forward, etc.) and verbal encouragement (e.g., “And?” “Then what?”). If she says something you don’t understand, ask for clarification (“Why?” “Can you go back to _______________?”

“I didn’t get what you meant by _______________.”).

Be aware of nonverbal cues to determine if she’s telling you anything she’s not actually saying, and follow the bread crumbs. Focus on the emotion behind the words: “Sounds like you’re feeling _______________, or is it something else?” “Why did you feel that way?” “Where is that coming from?”

When your friend is done, reflect what she told you by summarizing the story in your own words and asking, “Do I get you?” Finally, demonstrate an emotional connection to what you’ve heard: “When you told me _______________, it made me feel _______________.”

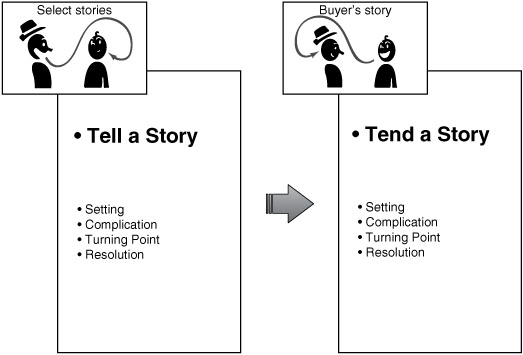

Exercise 6: Story Sharing on a Sales Call The goal of this exercise is to form an emotional connection with a new prospect.

Before you tell a story, soothe your prospect’s left brain by letting him know you have a plan for the meeting. For example: “What I’d like to do today is share my story with you and hear yours. Then we can ask each other questions to see if there’s a mutual opportunity.” Next, activate the prospect’s right brain with a brief story (of two to three minutes duration) from your inventory. When you’re done, pass the torch (e.g., “Enough about me. So, what’s your story?”) and tend to his story using empathetic listening skills. When your prospect is done, reflect what he told you by summarizing the story in your own words and asking, “Do I get you?” Figure 11.4 illustrates the give-and-take of storytelling and story sharing.

Figure 11.4 Storytelling and Story Tending

Prepare to be amazed.

Exercise 7: Getting Unstalled Remember Adam’s story in Chapter 6 about the dangers of going it alone? The goal of this exercise is to identify a stalled opportunity in your pipeline and build a story to unstall it—the right tool for the job.

Start by brainstorming the reason(s) you believe the opportunity is stalled. What would your buyer need to believe in order to get unstalled? For example, maybe your buyer needs to realize that the cost of not doing anything is greater than the cost of doing something. Your job is to build a story that conveys that belief. Draw on a personal experience in which your failure to act ended up costing you big time.

Use the story to move your buyer up to the next rung of the story ladder (see Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.5 Address a Stalled Opportunity in Your Pipeline by Building a Story That Will Move Your Buyer Up to the Next Rung of the Story Ladder

Exercise 8: Share Your Stories We’ve created a forum for readers to share stories and read other people’s stories at our website: www.storyleaders.com/shareyourstory. We’re especially interested in stories about how you used what you’ve learned in this book.

Now Get to Work!

By picking up and reading this book, by getting this far, you’ve demonstrated the desire to try something new. In other words, you’re on a journey, traveling the arc of change. You’re on your way to a story.

Expect to struggle. Expect complications. In your efforts to become a Story Leader, you’ll no doubt have a few dumbass moments along the way. But don’t be discouraged. Keep practicing. And remember, we’re all natural-born storytellers, even if some of us have gotten a little rusty.

Your turning point will come when you begin to see that the techniques in this book really work. You’ll know the moment: Aha!

And then there will be a resolution to your struggles. You’ll reach the high level of connection that fosters a collaborative, reciprocal sharing of ideas and beliefs—the type of communication that moves people to change.

The ability to influence others to believe what we believe isn’t limited to the very few. We can all do it. What we have discussed in this book is an approach that will let you see yourself—really see yourself—drawing upon the meaningful events of your life and sharing them with others. This is the fundamental way we connect with other people. And this connection is the basis for how people allow themselves to be influenced to change. It’s no longer a mystery: the ability to make these connections is what makes great salespeople great. It cannot be seen, but it is felt. You just have to take the leap and try it.