Incorporate “Free” as a Tactic, Not a Strategy |

Not long ago, a friend gave me a very expensive, made-to-order olive-and-purple coat that didn’t fit her correctly once it was made. Olive and purple makes my skin look gray, and the loose style makes me look like a box. But did I mention it was free? Despite the fact that I knew from the second I saw it that I would never wear it, I could not reject it. That is the power of free.

Businesses know the power of free: free razors to sell razor blades, free software trials, and free tchotchkes to lure you into booths at conventions and county fairs. Membership businesses are particularly sophisticated about free stuff. Many of the best membership businesses have a free offering that drives awareness and trial while simultaneously creating a community. Free membership creates stronger networks, which in turn attracts additional users, launching a virtuous cycle.

In many Membership Economy companies, the fixed costs are high, but the variable costs are very low—often virtually zero. This opens up all kinds of possibilities for free. Free trial is an old idea, but is attractive in the Membership Economy because of the ability to provide a taste for a limited period of time as well as to offer freemium—the subscription business model in which a free option provides ongoing value essentially forever.

Free content, or “content marketing,” is the practice of providing some free information as a means of building awareness and credibility with prospective members. It’s like advertising, except that the enterprise actually provides valuable content—research, news, ideas—instead of buying advertising and promotion. Other kinds of free include a free gift with purchase, a free lunch for hearing a pitch, a gift for visiting a store, a free latte for reaching a loyalty level, and more.

“Free” is not a business model; it’s merely a marketing tactic that helps generate revenue and deliver profits. Many companies, especially digital businesses, launch their businesses with free or deeply discounted offerings as a means of building interest and critical mass in their enterprise. Unfortunately, only some are able to sufficiently leverage free tactics, such as free samples, freemium models, or free content, to drive revenue. We talked about free in Chapter 7, but we didn’t get into specifics. Here’s how the successful companies make it work.

When to Use a Free Sample or Trial

When should you offer a free sample or trial of the organization’s product or service and how much should you give away?

Samples are good when companies need to educate prospects about a product’s value. Costco gives you samples so you can savor how delicious products are. Content-based subscription enterprises like Netflix and Spotify give prospects a free trial so they can see how easy the system is to use and how much great content is available.

One mistake companies make is to offer a free trial that does not provide the full experience. Sometimes they feel that they have to limit the benefits of the trial because the full experience is too expensive, but they run the risk of giving prospects the wrong idea about the experience. Prospects who experience a suboptimal trial have an inaccurate and negative impression of what they’d get if they joined.

Some companies tell me that they are reluctant to offer a free trial because they fear people could fill their need for the full benefits of membership during a finite test period. For example, if an association executive wanted to conduct one in-depth survey about members’ preferences and SurveyMonkey provided free trials for its premium offerings, the executive could sign up for SurveyMonkey’s premium offering, conduct the survey, and then return to the free account, without ever paying for the value. In cases such as this, however, it is likely that the prospect does not need a membership—the customer needs short-term access to your services. Create a short-term membership price instead.

When “Freemium” Makes Sense

Freemium (the word is common enough that The New York Times now uses it without qualification) is a level of membership that delivers ongoing value without charging a price. Technology has driven the cost of providing certain kinds of memberships almost to zero. There’s no reason why virtually any organization cannot offer something free on a regular basis. Freemium offers Membership Economy organizations three key benefits:

![]() It can build awareness and strengthen your pipeline of paying members.

It can build awareness and strengthen your pipeline of paying members.

![]() It can build a large community of members who connect with one another and provide value and prestige to key (paying) customer segments.

It can build a large community of members who connect with one another and provide value and prestige to key (paying) customer segments.

![]() It can attract new members by encouraging extended trials.

It can attract new members by encouraging extended trials.

Like virtually every other tactic, “freemium” also comes with risks:

![]() It can cannibalize paying members.

It can cannibalize paying members.

![]() It can condition people to expect a free service.

It can condition people to expect a free service.

![]() It can provide a subpar, flimsy, ineffective solution that annoys people.

It can provide a subpar, flimsy, ineffective solution that annoys people.

Freemium can be a great tool, but it’s important to remember that freemium is a means to an end—and that end, always, is revenue. Companies without a viral or networked component to their offering can still benefit from freemium as a means of driving a trial. Companies that have happy customers who eventually upgrade to a premium (paid) solution can justify a freemium model.

Having both free and paid offerings, however, can be tricky. If you offer too much value in the free offering, members have no incentive to upgrade. If you don’t offer enough value, you don’t attract anyone. Worse, an unsatisfactory freemium option can anger users who feel they’re being forced to upgrade to get the bare minimum value. Many companies have failed because they didn’t find the right balance between free and paid offerings and value.

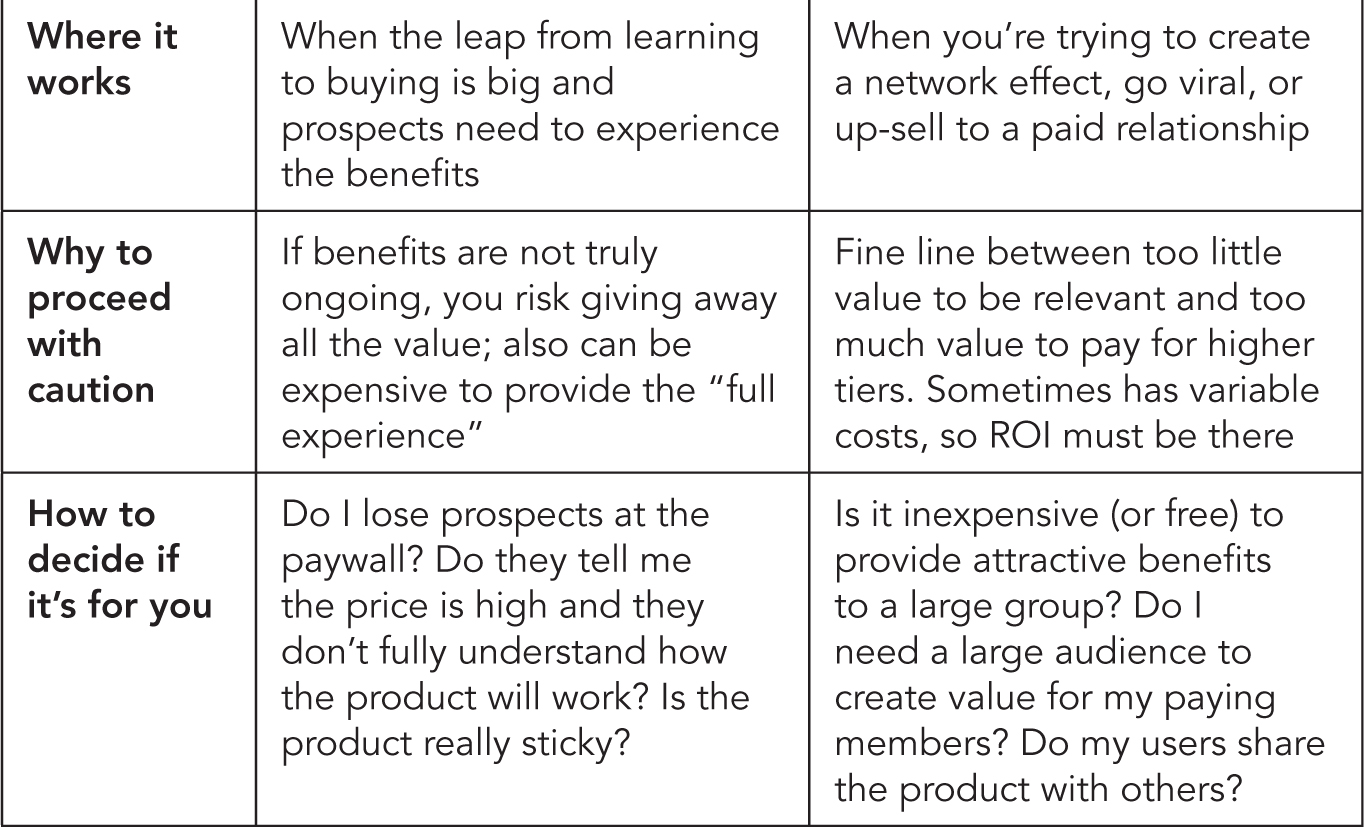

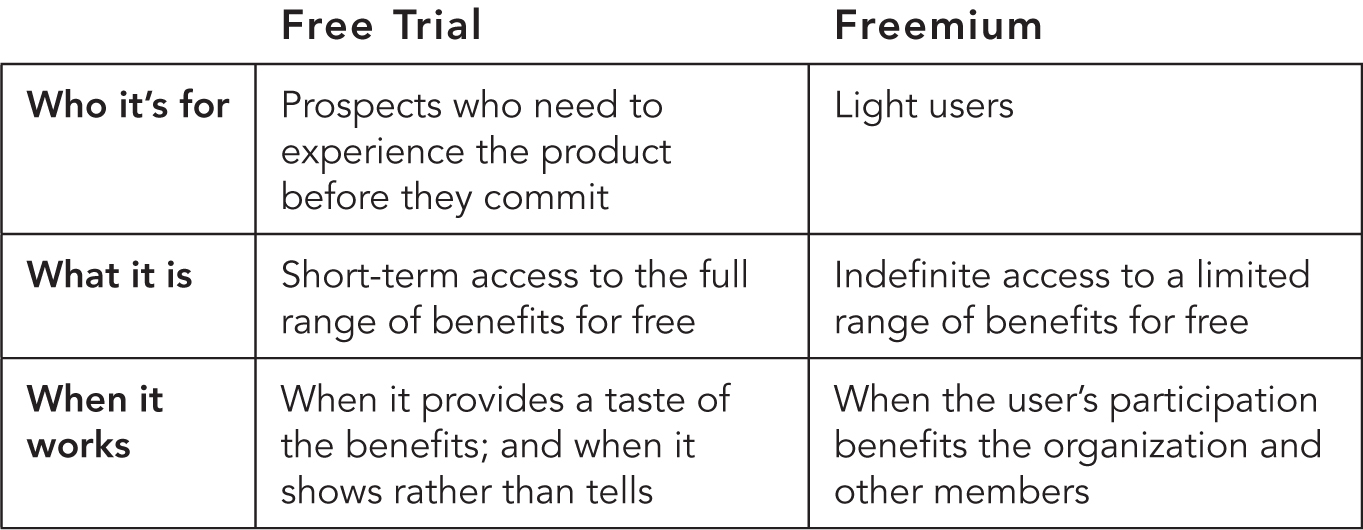

Remember that free is not a stand-alone strategy. A free trial and freemium are marketing tactics—ones that work only in concert with other important elements. There has to be a plan to generate revenue as a result of all the giving. Table 8.1 graphically outlines the differences between free and freemium.

Table 8.1 Free Trial Versus Freemium

Being able to include free offerings in your business strategy is like being a restaurant chef with a stash of wild truffles. You have a unique tool to create something really special, but you run the risk of overdoing it and ending up with an attractive yet unprofitable dish. What you really want is for free to serve as a growth engine that supports your other profitable lines of business.

When Free Did Not Make Sense

Offering a freemium option to subscribers is a tactic that can be effective with a broad range of organizations. Freemium can lead to upgrades, build awareness, and even create a network effect which adds value for each new subscriber. But sometimes freemium doesn’t make sense.

I have worked with several organizations that wanted to incorporate a freemium option into their business model. Often their management teams are well-acquainted with the prevailing theories about why organizations should provide value for free in order to be competitive. In some cases, these organizations already have successful subscription offerings with multiple price points and wonder if they could improve with a free offer. It is always worthwhile to look at a broad range of options for providing additional (even free) value to subscribers and prospects alike.

But it doesn’t always make sense to give the service away—even in a “lite” version. For example, in cases where there is no real interaction among users, such as accounting or security apps, there is no potential for viral marketing and network effects. So the only thing left would be using freemium as a means of gaining trial, with the potential to up-sell to a paid subscription. But in many cases, cost isn’t the barrier to subscribing, as prospects are concerned about the efficacy of the subscription service.

And sometimes offering a free subscription for a mission-critical service can give the wrong idea—signaling low value. For example, if I offered you “free spinal surgery” and you had chronic back pain, would the “free” offer be enough to make you go under the knife? Most likely, you’d be more concerned about the quality of the surgeon, the likelihood of the procedure being successful, or the expected recovery than you would be about just getting a good deal.

When it comes to free trials and freemium offerings, another key question to ask is whether making some part of the service experience free is going to remove enough friction to engage new users. In many cases, the biggest source of friction is setup—changing habits, entering data, and figuring out how the solution works. Freemium requires enough value right now to keep people interested while simultaneously creating value for the business overall.

Freemium requires a certain level of pricing elasticity (that is, if the price goes down, consumption goes up), as well as a variety of upgrade options. If your service is not a luxury but a necessity and you already have a large installed base of people willing to pay for the primary service, you may not want to offer a stripped down version for free. This lite version might backfire and cannibalize your paid offering, or worse, it might not offer enough value to be seen as useful at all.

Don’t despair if free isn’t for your business. At the core, this “problem” is actually quite desirable. If people had already proven that they were willing to pay for the service, then developing a free service as a means of increasing trial might not make sense. In fact, it might be full of risk—cannibalization, resetting expectations, and offering users an experience that isn’t up to your standards.

I suggest that you be creative in exploring free as a marketing tactic, but be open to the fact that your research may decisively remove “free” from the discussion. Too many companies are not disciplined in their use of free—and as a result find themselves without a viable source of revenue.

When Free Isn’t Really Free: The Napster Story

It should go without saying (but doesn’t always) that free doesn’t make sense when sharing for free violates laws. Perhaps the most famous example is Napster.

Founded in June 1999 by Shawn Fanning and his uncle John Fanning in the midst of the Internet bubble, Napster was originally conceived of as an independent peer-to-peer file-sharing service that was known for free online music. Its technology allowed people to easily share their music with other members, bypassing the established market for songs.

The benefits for members were vast. They gained access to a tremendous library of music and videos while helping others—all without spending any money. It was the first experience millions of music lovers had with downloaded music and the opportunity to access new and rare single tracks without having to buy an entire album. And of course it was free!

Unfortunately, this approach led to massive copyright violations of music and film media as well as other intellectual property. Effectively, the free music was made possible by mass theft. Napster’s original service was shut down by court order in July 2001. Later that year, Napster paid a $26 million settlement for past, unauthorized uses of music, as well as an advance against future licensing royalties of $10 million.1 To pay those fees, Napster tried to convert its free service to a subscription system. But it had already “taught” its users not to pay for access to music. The company was acquired, first in 2002 by software company Roxio, and then in 2008 by retailer BestBuy, and then in 2011, merged into Rhapsody, the streaming media service. At the time of the BestBuy acquisition, Roxio claimed about 700,000 paying subscribers, down from a reported 25 million users at its high in around 2001.2

Napster’s pioneering efforts paved the way both for peer-to-peer file-sharing sites such as Gnutella and Freenet as well as music subscription sites like Sky Songs, eMusic, and Spotify. But Napster was also responsible for slowing the transition of music to the digital world. Nearly a decade passed before paid digital music became mainstream. Ultimately, what Napster did well was to understand what the users really wanted and force the rest of the industry to deliver.

What can we learn from Napster about giving stuff away for free? With the right enabling platform, people’s enlightened self-interest motivates tremendous sharing and cooperation and the creation of real value. The Membership Economy can lead to whole new ways of interacting with content and with people. Keep in mind, however, that:

![]() A business can’t make money if no one is paying, even with 25 million users.

A business can’t make money if no one is paying, even with 25 million users.

![]() Moving from free to paid for the same service is extremely difficult, regardless of the value.

Moving from free to paid for the same service is extremely difficult, regardless of the value.

![]() If you give stuff away, make sure it’s yours to give away!

If you give stuff away, make sure it’s yours to give away!

Remember

Silicon Valley is littered with failed companies that gave away any chance of success. While these companies are invariably shocked by their failure, this result wouldn’t surprise anyone who has ever been warned that people won’t buy the cow if they can get the milk for free.

There are lots of times when free does make sense—when users themselves, by using the service, create incremental benefits for future users; when the free users organically “touch” potential new subscribers and build awareness; and occasionally when trial is necessary to hook users on the service. Free membership in the role of “free trial” is most successful if there is a natural reason that certain users are likely to upgrade to a paid service—usually for increased volume, features, or service levels.