What is law librarianship?

The academic law library is the centre of activity for law students, academics, lawyers/attorneys, judges, members of the public and whoever else finds the need to use them. This chapter defines law librarianship as a specialization in the field of library science by reviewing the history of the profession in selected jurisdictions. This chapter reviews developments in law librarianship in general; it discusses the education, qualifications and competencies required to practice the profession in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Nigeria. Accreditation exercises can be daunting, time-consuming and there have been varying opinions about their continued existence in legal education. This chapter reviews the accreditation practices and requirements in some selected jurisdictions noting that the United States’ model is the most intense of all. A brief overview of the role and functions of other types of law libraries is also discussed.

Keywords

Law librarianship; law libraries; law schools; accreditation; qualifications; structure; autonomy; centralized

Law librarianship is a specialized field in the practice of librarianship. Librarians with this focus work and practice in law libraries belonging to academic institutions, government departments and agencies such as the Attorney General’s office, Courthouses, law firms and legislative or special libraries.

Qualifications for law librarians

Unlike the legal profession, Law Librarians do not have licensing and regulatory bodies that review the standards for the profession. However, in some countries such as the United Kingdom and Nigeria there are regulatory bodies for the librarianship profession. This is discussed later in this chapter. It is common to find that law librarians have university degrees in law and Masters in Library Science. This is very common in many academic and government law libraries in the United States and Canada. There has been a lot of discussions as to whether or not a librarian working in a law library needs a dual degree. Each country has its own standards, expectations and practices that have also been influenced by a number of factors over the years such as finances, work experience, institutional standards, hiring practices, accreditation requirements and other professional training options.

While obtaining a law degree is not mandatory for anyone who wants to work in law libraries, it will always be of great benefit when carrying out professional duties. In the academic law library, one advantage of having a law degree is that it gives that person a proper understanding and knowledge of the materials in a law collection as well as an understanding of student and faculty expectations. From a practical point of view, Demers (2012) noted the usefulness of a law degree, especially when answering questions at the reference desk.

Similarly, the knowledge of foreign, comparative and international law (FCIL) is emerging as a requirement for law librarians applying to work in academic law libraries. Law librarians in this position are referred to as FCIL librarians and this is a common practice and trend in many law schools in the United States. An FCIL librarian is familiar with the laws and practices of one or more jurisdictions in a region. For example, such a librarian may be knowledgeable in Asian laws in which case they may know about the laws of China, Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia or other countries in that continent. Or an FCIL librarian responsible for the Caribbean will likely understand the laws of most countries in that region such as Trinidad & Tobago, Jamaica, Barbados etc. These librarians usually understand the legal systems of multiple jurisdictions. Knowledge of international law means an understanding of the role and concepts of international law and an understanding of the practices of international organizations such as the United Nations and its organs. Researchers and professors outside of the law school but within the university rely on the expertise and knowledge of FCIL librarians when they need information about other foreign jurisdictions.

Another emerging requirement for academic law librarians is fluency in languages other than English such as French, Spanish, German, Italian and Chinese. Many academic law libraries’ job postings have indicated the requirement of fluency in these languages lately. One explanation for requiring the knowledge of a foreign language may be the global trend in law practice for foreign trade with emerging markets. Lawyers and legal researchers need information from foreign jurisdictions that will likely be available in the foreign language. A librarian who understands and can translate the information will naturally be a useful member of the team. Rumsey, a highly respected foreign, comparative and international law librarian in the United States observed that: “Historically, French, German, Spanish and Italian have been the most common languages used by FCIL librarians. With increasing legal and financial interest in China, however, knowledge of Chinese might be even more marketable.”

Gaining a dual degree may be an expensive venture, but from a practical point of view, and from my experience, a law degree always comes in very handy and is extremely useful when working in an academic law library. As an administrator in an academic law library, you come into contact with other administrators and academics in the faculty; the knowledge of the law elevates the status and that helps to command some respect from faculty members and students. Note that this does infer that those Law Librarians without a law degree do not command any respect from the academic community.

A law librarian with the dual degree understands the language of the profession and its nuances. For example, this background is helpful for understanding the “territorial” attitude of law students. In all the institutions in which I have worked I have come to the conclusion that this attitude is the same globally. Law students love their space and don’t enjoy seeing non-law students studying there even if they are genuinely there for academic purposes. I remember that when I was in law school, the law library was exclusively located in the basement of the university library but it had the level of comfort that an undergraduate could wish for; it was very obvious that other students in the university were not welcome at this location!

Understanding this cultural difference will help administrators when planning services for the academic law library. This will equip them with a broader understanding of user needs when creating library policies related to seating, readers services among others.

The following are some of the educational qualification practices of librarians working in academic law libraries in Canada, United States, United Kingdom, South Africa, The Caribbean and Nigeria:

Canada

In Canada, many of the law library directors in Canadian law schools have a degree in law and librarianship. (Seven of the directors have dual degrees i.e. law degrees and a master’s degree in library science). The Canadian Association of Law Libraries is a professional membership body of law libraries in Canada. This body is not a licensing or regulatory body and so they do not have any required qualifications for law librarians. The executive board of the Canadian Association of Law Libraries (CALL) is in the process of developing and creating its competencies for law librarianship.

The standards of accreditation for law schools in Canada are different from that of the United States; but there is no requirement about the educational qualification of law librarians.

United States

The American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) is the professional organization in the United States responsible for providing the promotion and advancement of law libraries. The AALL is a membership organization with about 5,000 members. Similar to Canada, the organization is not a licensing body. However, the Career website on educational requirements for the law librarianship profession, the American Association of Law Libraries stated that the majority of law librarians have a graduate degree in library and information science but the requirement for a law degree depends on the institution. Nevertheless, there are some libraries that have lawyers and attorneys without a law degree working in their institutions.

The American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) has defined the law librarianship profession by creating a list of competencies for members of this profession based on “knowledge, skills, abilities and personal characteristics”. The list of these competencies are available here - http://www.aallnet.org/main-menu/Publications/spectrum/Archives/Vol-5/pub_sp0106/pub-sp0106-comp.pdf.

The AALL competencies are widely acknowledged and practiced all over the world and have been used for recruitment and promotion purposes. The competencies are divided into Core and Specialized areas which are acquired at different stages of one’s career. The Core competencies are more general, apply to everyone and will have been acquired early in one’s career. I have decided to highlight the following skills:

• Strong commitment to excellent client service

• Recognizing the diverse nature of a library’s client

• Understanding the culture and context of the parent institution

• Demonstrating knowledge of the legal system and the legal profession

• Exhibiting leadership skills, regardless of position within management structure

• Exhibiting understanding of a multidisciplinary and cross-functional approach to programs and projects within the organization

• Recognizing the value of professional networking and participating in professional associations

• Actively pursuing personal and professional growth through continuing education.

The above are critical benchmarks that every professional law librarian should refer to at the beginning of their career and periodically check their progress and advancement in line with these requirements. There is no identification of the number of years that counts as early career but from my experience a professional should have been able to build and develop all these competencies in the first eight years of working in this field.

The Specialized competencies are skills required for different areas of specialization and have been divided into:

These are library-related areas and it has been acknowledged that it is possible for a librarian to be specialized or have responsibilities in more than one of these areas.

Many law librarians that I have interacted with in North America have built their careers in line with these competencies regardless of whether or not they have dual degrees.

Standard 603(C) of the American Bar Association standards for Approved Law Schools states that: “The director of a law library should have a law degree and a degree in library or information science and shall have a sound knowledge of and experience in library administration”. Using this requirement a number of law schools in the United States strive to follow this criteria when making appointments and this can be clarified from job advertisements posted on the job site of various law schools and on the website of the American Association of Law Libraries.

United Kingdom

Law librarians in the United Kingdom are classified among legal information professionals according to a publication of the British & Irish Association of Law Librarians (BIALL). The main qualifications suggested for entry to the profession are either an undergraduate or postgraduate degree in librarianship and information studies noting that “a law degree may be an advantage but not essential”. The BIALL as a professional association continuously organizes training sessions on legal information sources for its members and other interested parties. The Chartered Institute of Librarians and Information Professionals (CILIP) is responsible for promoting and supporting the librarianship profession in the United Kingdom.

Law schools in the United Kingdom are guided by a set of comprehensive and flexible standards created by the Society of Legal Scholars. These standards provide guidance on the provision of services, staffing, management, resource, access, delivery policies, equipment and building. They are reviewed periodically based on surveys sent out to law schools through the British and Irish Association of Law Libraries. Standard 1.3 states that it is desirable that a law librarian should hold a legal qualification. However, in the results of the survey for 2007/8, 75% of university libraries in the United Kingdom did not meet this requirement.

The Caribbean

The Caribbean in this context represents the English-speaking territories: namely, Antigua, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, The British Virgin Islands, The Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent, Trinidad and Tobago, The Turks and Caicos. There are no strict requirements for the qualification of law librarians in these countries. In the Faculty of Law, University of The West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbados, the head of the library past and present both have law degrees. Similarly, at the Council of Legal Education libraries in Trinidad, Jamaica and The Bahamas, there are no strict requirements for a law degree but past and current librarians have dual degrees.

The Department of Library & Information Studies, University of the West Indies (UWI) offers undergraduate and graduate programs in library and information studies for librarians in the Caribbean. Historically, many law librarians from the Caribbean studied in the United Kingdom, United States and Canada.

South Africa

The Organisation of South African Law Libraries http://www.osall.org.za/ is the national law library organization. One of its objectives is: “To enhance and develop the practice of law librarianship and provide opportunities for professional growth for law librarians and training for those who work with legal materials in libraries or information centres in South Africa”. Many of the library schools provide training for library school students who want to specialize in law librarianship.

Nigeria

In Nigeria there are two organizations that are responsible for the accreditation of law programs offered in universities. They are the Council of Legal Education and the National Universities Commission. Both organizations require that the head of an academic law library must have a Masters degree in Library Science as well as a degree in law and they must have been called to the Nigerian Bar. Note, however, that everyone who is practicing as a librarian in Nigeria must have passed through the chartership process through the Librarians Registration Council of Nigeria (LRCN). The Nigerian Association of Law Libraries is the professional membership body responsible for leadership and promotion of law libraries, but they do not have any firm requirements for the education of law librarians. The Nigerian Library Association coordinates the activities of all libraries and librarians in Nigeria; this body does not have any specific educational qualifications for law librarians. Similarly there is the Librarians Registration Council of Nigeria (LRCN), a body created by the Federal Government of Nigeria whose mandate is to determine the standards and skills of chartered librarians. The LRCN does not have any clear requirements for the qualification of law librarians.

Education of law librarians

Librarians working in the law library attend library school to attain professional library degrees, usually a graduate degree Master of Library & Information Science (Studies) MLIS, MLS, MISt; but note that the names and acronyms varies depending on the awarding institutions. A very common practice in many countries is for librarians to study librarianship and eventually opt to study law along the line. But the history of academic law librarianship in the United States is the opposite as law students were some of the first group of persons to be hired to manage law libraries, which means that they did not initially have any librarianship qualifications. In the past two decades, the experience has been vice-versa with practicing lawyers/attorneys going back to library school and embracing law librarianship as a second career. Law graduates are also finishing law school and going back for graduate studies in library science.

Education for law librarians has evolved over the years from just acquiring skills in librarianship. Some library schools now have combined programs that qualify persons immediately upon graduation to work in a law library; dual programs are now available in law faculties and library schools in the United States and Canada. Students who enroll in such programs graduate with a Masters in Library and Information Science and a Juris Doctor (equivalent of LL.B in Commonwealth countries). In the early 1970s having a dual degree was the trend and was a great advantage for those who had them. Berring (2013) noted that in the United States in 1975 the profession of law librarianship was ablaze as newer law schools were being set up and the older generation of law library directors were retiring so having a dual degree created opportunities and was a gateway for advancing quickly in this career. See Appendix 2 for a list of dual programs in Canada and the United States.

Academic law libraries

The academic law library exists to meet the research and teaching needs of students and faculty and in some instances members of the public; but the primary patrons are students and faculty. This means that the services provided will accommodate the needs of this clientele. The collection will be developed and built to facilitate and enhance teaching and research of faculty and students.

Structure of academic law libraries

The administrative reporting structure in academic law libraries remains a contentious and debatable issue all over the world. The most common ones are autonomous and centralized structures. Some law libraries are independent of the main university library while some function directly under the university library. Where the law library is autonomous, the head of the law library reports to the Dean of the Law School and the library budget and administration are managed through them. This is very common in law schools in the United States. Under the centralized system, the law library functions under the main library, the head of the law library reports to the Dean of Libraries/University Librarian or to the Associate University Librarian who is in charge of unit libraries and the budget is administered through that office. In instances where the law collection sits within the main university library among other subjects there is usually a librarian designated to manage this collection who reports to the Dean of Libraries/University Librarian. In some institutions, the head of the law library reports to both the Dean of the Law School and the Dean of Libraries/University Librarian. This structure exists in the Cornell University Law Library, University of Buffalo Law Library and the Vanderbilt Law Library.

One of the benefits of an autonomous law library is the assurance that the library will receive more financial support from the law school especially from donations that are received from alumni, law firms and other corporations. In many of the jurisdictions where I have worked and practiced as a law librarian, there is the general assumption that the legal profession is elitist and its members are wealthy so the law school will likely receive more substantial donations, gifts and endowments than other areas of an institution.

In the ABA Standards for Approval of Law Schools 2013–2014 there is a preference for an autonomous structure, especially in terms of managing the growth and development of the law library. See Standard 602 - http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/misc/legal_education/Standards/2013_2014_standards_chapter6.authcheckdam.pdf.

Under the centralized system, the university library distributes the funds and resources equally among all the departmental and unit libraries. Equal distribution may be fair and equitable but the cost of law materials makes this an impracticable option that usually causes a lot of friction between university management and the head of the law library. Nevertheless, in a centralized system, the law library may be treated like any other branch library. And if the library is located within the law outside the main library; the distance tends to isolate the staff from others in the centralized system. From my experience, the partnership between the stakeholders in the centralized system requires a great sense of understanding and the willingness to collaborate when making financial decisions.

The library building is usually situated on the grounds or the same facility as the law school, especially where they are autonomous from the main university library. One advantage of this is that it provides exclusive access to the library facility for law faculty and students.

There have been many criticisms of both structures and decisions are usually made by the university administration based on accreditation standards. In the United States, many of the academic law libraries follow the standards required by the accreditation bodies. Price (1960) noted the disparity between an autonomous and centralized system: “The principal stigmata of the so-called “autonomous” law school library are closer budget control by the law school, hiring and discharge of library personnel, and book-selection autonomy. It is in the discussions of the exercise of these functions, as between director and dean that the most significant analytical fallacies occur…. With a library-minded dean, conscious of the place of the law library in his scheme of things and willing to fight for it, success within budget limitations is almost assured under either system. On the other hand, if the dean is indifferent to the library needs, or weak, the autonomous library is a mess (and for every unsatisfactory law library in a centralized system, I can show you an autonomous law library just as bad). Contrariwise, in a centralized system, the law library may or may not be a stepchild, depending upon how enlightened the director is and how willing he is to cooperate in solving the peculiar problems of the law library.”

Price’s observation continues to exist and dominate many academic law libraries, which means that library directors need a lot of tact and a high sense of professionalism in tackling these issues. Many law schools have competing needs for the limited budget so it will take a dean who is library-centric and focused to clearly articulate the financial needs of the library in their planning.

Milles (2004) suggested that there are varying models that academic law libraries can apply: “Law schools exist largely, but not solely, to train lawyers for private practice and public interest work. Law libraries exist to serve that goal. The autonomy of the law library must be viewed as a means toward achieving that goal, not an end in itself. Consideration must be given to the ways in which autonomous decision-making serves those goals, as well as the ways in which cooperation and collaboration contribute to meeting those needs. It no longer makes sense to insist on the dualistic conception of law libraries as either autonomous or branch libraries, ignoring the range of shading in between.

“Developments and trends such as availability of electronic legal resources and increasing multidisciplinary approach to legal research calls for academic libraries to rethink the structuring of libraries from autonomous and centralized systems.”

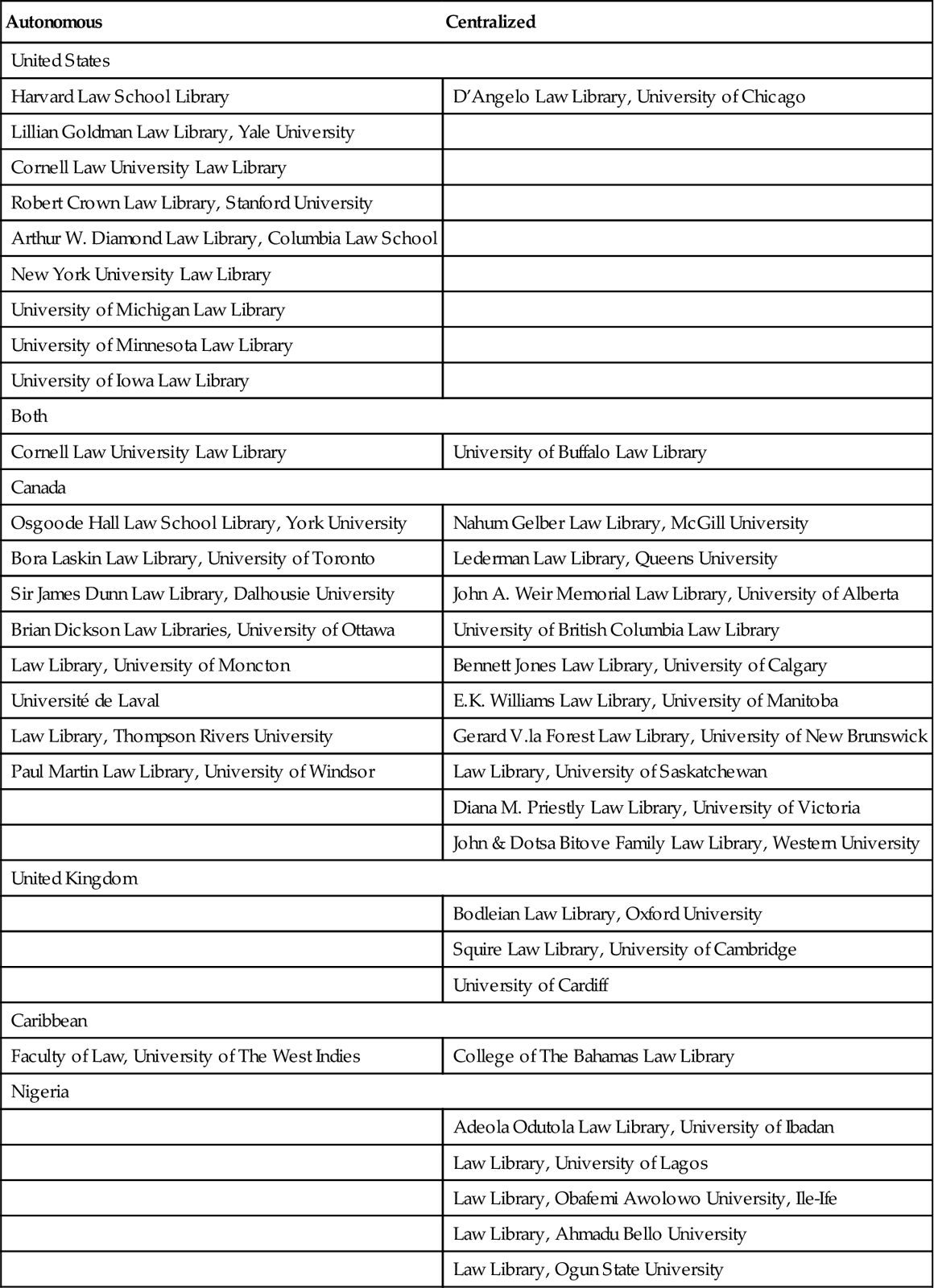

Table 1.1 below is a sample list of the structure of academic law libraries in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, The Caribbean and Nigeria. The selected libraries are publicly funded institutions except for the United States which is a combination of public and private.

Table 1.1

Examples of administrative structure in academic law libraries

| Autonomous | Centralized |

| United States | |

| Harvard Law School Library | D’Angelo Law Library, University of Chicago |

| Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale University | |

| Cornell Law University Law Library | |

| Robert Crown Law Library, Stanford University | |

| Arthur W. Diamond Law Library, Columbia Law School | |

| New York University Law Library | |

| University of Michigan Law Library | |

| University of Minnesota Law Library | |

| University of Iowa Law Library | |

| Both | |

| Cornell Law University Law Library | University of Buffalo Law Library |

| Canada | |

| Osgoode Hall Law School Library, York University | Nahum Gelber Law Library, McGill University |

| Bora Laskin Law Library, University of Toronto | Lederman Law Library, Queens University |

| Sir James Dunn Law Library, Dalhousie University | John A. Weir Memorial Law Library, University of Alberta |

| Brian Dickson Law Libraries, University of Ottawa | University of British Columbia Law Library |

| Law Library, University of Moncton | Bennett Jones Law Library, University of Calgary |

| Université de Laval | E.K. Williams Law Library, University of Manitoba |

| Law Library, Thompson Rivers University | Gerard V.la Forest Law Library, University of New Brunswick |

| Paul Martin Law Library, University of Windsor | Law Library, University of Saskatchewan |

| Diana M. Priestly Law Library, University of Victoria | |

| John & Dotsa Bitove Family Law Library, Western University | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Bodleian Law Library, Oxford University | |

| Squire Law Library, University of Cambridge | |

| University of Cardiff | |

| Caribbean | |

| Faculty of Law, University of The West Indies | College of The Bahamas Law Library |

| Nigeria | |

| Adeola Odutola Law Library, University of Ibadan | |

| Law Library, University of Lagos | |

| Law Library, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife | |

| Law Library, Ahmadu Bello University | |

| Law Library, Ogun State University | |

History of academic law libraries

Academic law libraries have evolved from the collection of practicing lawyers as many law school libraries were created from book donations from the libraries of these individuals. In the United States the foundation of larger institutionalized law library collection in the 19th and 20th century was developed from books in the private collections of lawyers. Roy Mersky recalled that the Founders Collection at the Yale Law Library is made up of the collections of Seth P. Staples, Samuel J. Hitchcock and David Daggett; while Edward C. Kent donated his collection to Columbia Law Library in 1911; Cornell acquired collections of Merrett King (1886) and Nathaniel Moak (1893).

In the United Kingdom, the oldest academic law library is the Bodleian Law Library at Oxford University, it originated from an endowment from Duke Humphrey. Jeffries (1989) recalled that the academic institutions collected law books but there were no librarians as the position was not treated as a professional but janitorial one.

Canadian law school libraries have also been managed by administrators who were not librarians but who had legal backgrounds. However, the oldest academic law library in this jurisdiction was established by a distinguished and respected law librarian whose collection development skills created a leading collection in the Commonwealth. One of the early donations to the Osgoode Hall Law School library came from the estate of the late Phillips Stewart, a law student who died before he could complete his education but gave a substantial amount which was endowed specifically for buying books for the library. This endowment is still being used for this purpose.

In Nigeria, many of the academic institutions were established after its independence from Great Britain. During the colonial administration, the common practice was for students to travel to the United Kingdom for their education. However, after 1960, it became necessary to train lawyers in local laws. The Faculty of Law, University of Nigeria, Nsukka is the oldest which includes a law library. This library and those of the first generation universities such as University of Lagos, Obafemi Awolowo University (formerly University of Ife) don’t have separate law libraries; the law collection is part of the main university library. The Faculty of Law at the University of Ibadan was the last to be established among the first generation universities; its library is situated on the grounds of the law school but it is centrally-administered by the main university library. The law library building in Ibadan is a donation from the estate of Nigeria’s prominent industrialist, the late Chief T. Adeola Odutola, and the building is named after him.

Accreditation & standards for academic law libraries

Just like other professional courses such as medicine, dentistry etc., the regulatory bodies responsible for the legal profession in some jurisdictions around the world require that law libraries meet certain standards before the law school program is approved. The essence of accreditation is to ensure that the institutions provide adequate and appropriate resources for the programs being offered. Libraries should provide all the resources to support teaching, learning and research. The accreditation exercise involves site visits to the different institutions by a selected team, which always includes librarians. In the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Nigeria; the regulatory bodies have specific requirements that must be met before law programs can be approved. In the Caribbean, each country has its own standards and requirements; I have outlined below those of Barbados, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago.

In Trinidad and Tobago, the Accreditation Council of Trinidad and Tobago Act established the body that is responsible for “conducting and advising on the accreditation and recognition of post-secondary (sic) and tertiary educational and training institutions, programmes and awards, whether local or foreign, and for the promotion of the quality and standards”. The Accreditation Council is responsible for the quality assurance and accreditation of professional courses being offered in tertiary institutions in that country. More information is available on their website here - http://www.actt.org.tt/index.php/services/accreditation.

The relevant institutions are the Faculty of Law Library, University of The West Indies, St. Augustine campus.

The University Council of Jamaica is responsible for national quality assurance in Jamaica. The relevant institution is the Faculty of Law Library, Mona Campus. More information about the organization is available here - http://www.ucj.org.jm/content/what-accreditation-0.

The Barbados Accreditation Council was established by the Barbados Accreditation Council Act of 2004 to provide registration, accreditation and related services in post-secondary and tertiary institutions in Barbados. The Faculty of Law, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados falls under the jurisdiction of the Barbados Accreditation Council. More information about the Council is available here - http://www.bac.gov.bb/Accreditation.htm.

In Nigeria, there are two institutions that are responsible for the accreditation of law schools:

2. Nigerian Universities Commission (NUC) http://www.nuc.edu.ng/pages/pages.asp?id=27

The Nigerian Universities Commission is an arm of the Federal Ministry of Education. One of its mandates is “to ensure quality assurance of all academic programmes offered in Nigerian universities”. Every five years, the Commission’s Quality Assurance team conducts accreditation site visits to public and private institutions evaluating their resources, equipment and facilities to ensure that they meet the standards required to facilitate the different programmes.

The Council of Legal Education is the body responsible for the training and regulation of the legal profession in Nigeria; they also manage the schools where practical training is offered after undergraduate legal education. This body is responsible for the accreditation and approval of law programs in public and private universities in Nigeria. They evaluate law programmes by conducting site visits and they have their own standard requirements which must be met before any law programme can be offered in universities. The Council of Legal Education provides a list of materials which are required for any academic law library in Nigeria. These are the items that will be during site visits to institutions.

United States

The American Bar Association (ABA) and the Association of American Law Schools (AALS) are the two organizations responsible for the regulation of the legal education in the United States. The ABA standards are reviewed and updated annually and are available here – http://www.americanbar.org/groups/legal_education/resources/standards.html.

Byelaw 6 (8) of the AALS states as follows:

a. A member school shall maintain a library adequate to support and encourage the instruction and research of its faculty and students. A law library of a member school shall possess or have ready access to a physical collection and other information resources that substantially:

i. meet the research needs of its students, satisfy the demands of its curricular offerings, particularly in those respects in which student research is expected, and allows for the training of its students in the use of various research methodologies;

ii. support the individual research interests of its faculty members;

iii. serve any special research and educational objectives expressed by the school or implicit in its chosen role in legal education.

b. The library is an integral part of the law school and shall be organized and administered to perform its educational function and to assure a high standard of service.

c. A member school shall have a full-time librarian and a staff of sufficient number and with sufficient training to develop and maintain a high level of service to the program.

http://www.aals.org/about_handbook_bylaws.php.

There are other accreditation bodies for post-secondary and tertiary institutions but I have chosen to focus on the ones relevant to academic law libraries. The standards of accreditation in law schools in the United States is a long standing and established practice. Many countries like Nigeria have designed and structured their accreditation standards against the American model considering its consistency over the years.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the Society of Legal Scholars came up with a Statement of Standards for University Law Library Provision which serves as a guide for the operation of an academic law library. They were drawn from the opinion and contributions of legal scholars, law librarians and government bodies. These standards are updated following the trends of activities in academic law libraries in the United Kingdom in the form of a survey which is conducted by members of the British and Irish Association of Law Librarians. They contain requirements for minimum holdings for a law library that take into consideration the number of students at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, development in the publication format (print versus electronic), curriculum changes etc. The list of materials in the standards serves as guidance for law library administrators in building their collection. There was a major revision of the Statement in 2009 as a result of major developments in legal education and “Particular attention was paid to the balance between print and electronic sources of information, remote access to information resources and services, the use of wireless technology, the relative roles of the library and the law school in teaching research skills, the growing incorporation of information literacy objectives, the comprehensive collection statements, and the standards for franchising and distance learning.”

Note that the Statement is not an accreditation tool; there are other bodies responsible for the accreditation of higher education and tertiary institutions in the United Kingdom.

Canada

The Federation of Law Societies of Canada is responsible for the regulation of the legal profession in Canada. This body does not have any guidelines or standards exclusively for academic law libraries except in a recent document prepared by a task force set up in June 2007. As part of the requirements for a new law school in the Task Force recommendations: “The law school maintains a law library in electronic and/or paper form that provides services and collections sufficient in quality and quantity to permit the law school to foster and attain its teaching, learning and research objectives”. This is the closest standard required for academic law libraries in Canada, and there are no other requirements for the position of law librarians or library directors. It is usually left to the institutions to decide.

There are provincial quality assurance bodies that facilitate accreditation of higher education in Canada; for example there is the Ontario Universities Council on Quality Assurance which is responsible for assuring the quality of all publicly funded university programs and overseeing the regular audit of each university’s quality assurance processes.

There also exists a set of standards prepared by the Canadian Academic Law Library Directors – Canadian Academic Law Library Standards (2007).

Chapter 6 explains in detail the standards required for library and information resources with respect to library collection and law librarian positions.

It should be noted that some institutions have chosen to ignore some of the required standards and have been able to survive, which leads one to question whether it is still relevant to have such rigorous exercises. Accreditation standards have been described as a toothless but bothersome dog by Berry (2013).

I had the opportunity to participate in two successful accreditation visits by both the Council for Legal Education and the NUC while working at the Adeola Odutola Law Library, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Both exercises were very intense but the law library was ranked as one of the very strong areas of the law school.

Other types of law libraries

Court house

The court house libraries are established to serve the courts. The courts in any jurisdiction are at different levels and in most countries the Supreme Court is the highest court. Each court has its own library and the collection is mainly for the use of the judges and sometimes to members of the legal profession. Most court libraries are not open to the public with the library residing within the court premises. Many of these courts provide excellent document delivery services as well as maintain an updated website with useful information. See Appendix for a list of courts in some Commonwealth countries and the United States.

Attorney-general’s office

The Attorney-General’s Office is also known as the Ministry of Justice in some jurisdictions. The libraries are set up for the use of government lawyers. Depending on the jurisdiction, each state or province has its own library and there is one assigned to the federal level. This is the practice in Canada, United Kingdom, Nigeria, The Bahamas, Barbados, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Legislative

Legislative libraries are found in the parliaments of most countries. This type of library is established for the use of members of the legislative assembly and their research assistants. They are not open to members of the public. The Library of Congress and the Library of Parliament, Canada, are examples of legislative libraries.

Law firms

The library in a law firm is set up to meet the needs of legal practitioners in private practice. Depending on the size of the law practice it is not uncommon to find very large law libraries to facilitate legal research or just a small collection for a solo practitioner. In cases where it is a very large practice with law offices in different parts of a country or the world, the library will tend to share its resources. These libraries are strictly for private use and are not open to the public.

Special libraries

The collections in these types of libraries are mostly for research. Examples are the Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, London and the Swiss Institute of Comparative Law. These libraries are for the use of researchers affiliated with these institutions while visiting researchers are provided access by request.

Conclusion

Law libraries are an essential tool for the training of potential legal practitioners and it is necessary to require that they are properly and adequately maintained. This chapter has discussed the history of academic law libraries, the education and training of law librarians who are the essentials who manage the functions and operations of the library, the administrative structures that exist in law libraries and future recommendations.