Business Modeling

Abstract

A descriptive model of a whole enterprise consists of vision, mission statements, goals, strategies, and realizing tactics, among other things. The OMG business motivation model (BMM) provides a structure by means of which those terms can be kept apart. Hence it ensures clarity in creating an enterprise model. This chapter explains the main features of the BMM.

The BMM provides a structure for defining and developing a business plan by describing which purposes an enterprise pursues by which means. The BMM is an OMG standard and describes, on the one hand, the goals of an enterprise with a superior vision and, on the other hand, the associated implementation strategies and tactics with their superior missions. The BMM only defines the structure and properties of the BMM elements such as vision, goals, and so on, and describes their semantics. The top-most areas of BMM are: end: describes the vision of the enterprise and the goals and objectives derived thereof; means: describes which means the enterprise deploys to meet the enterprise objective; influencer: describes to which influencers the enterprise is exposed for instance, current market trends, actions of competitors, or internal influencers such as the IT infrastructure; assessment: assesses neutral influencers on goals and means used; and external information: addresses further important topics of business modeling that are not part of BMM but of other standards. The end area is divided into vision and the desired results, which in turn, are subdivided into goals and objectives. The means area is subdivided into missions, courses of action, and directives. The course of action is split into strategies and tactics, and directives into business policies and business rules. The influencers are distinguished by external and internal influencers with reference to the enterprise. The external information comprises organization units, business processes, and business rules.

Keywords

Business motivation model; BMM; Vision; Mission; Strategy; Tactic; Goal; Objective; Business rules; Business policy

People who have a vision should go see a doctor.

Helmut Schmidt

What do you need to create a model of an enterprise? Right. Pen and paper. But which elements do you want to depict?

The business motivation model (BMM) provides a structure for defining and developing a business plan by describing which purposes an enterprise pursues with which means. Moreover, it can be used to relate (technical) solutions and developments of the enterprise to business considerations.

It therefore, provides a—if you will—globally uniform comprehension of rather abstract terms, which often totally get mixed up in common speech. You cannot describe the difference between vision and mission straight away, can you? What about strategy and tactic? Neither? Alright, then you should continue reading.

5.1 The Business Motivation Model

The BMM is a standard of OMG and describes, on the one hand, the goals of an enterprise with a superior vision and, on the other hand, the associated implementation strategies and tactics with their superior missions.

No Notation for BMM

There is no standardized notation, but only abstract syntax. So the BMM only defines structure and properties of the BMM elements such as vision, goals, and so on, and describes their semantics.

BMM Area

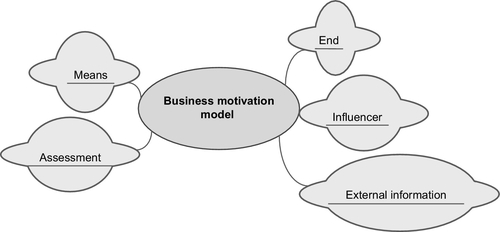

The top-most areas of BMM are the following (Figure 5.1):

• End—Describes the vision of the enterprise and the goals and objectives derived thereof.

• Means—Describes which means the enterprise deploys to meet the enterprise object. This does not refer to employees or money, but to missions, strategies, and tactics.

• Influencer—Describes to which influencers the enterprise is exposed, for instance, current market trends, actions of competitors, or internal influencers such as the IT infrastructure.

• Assessment—Assesses neutral influencers on goals and means used, for example, that the opening of a rival enterprise nearby poses a threat for the enterprise.

• External information—Addresses further important topics of business modeling, which are not part of BMM, but originate from other standards, for example, business processes and organization structures. In this area, BMM defines how these topics are incorporated in the BMM.

5.1.1 Complete BMM Overview

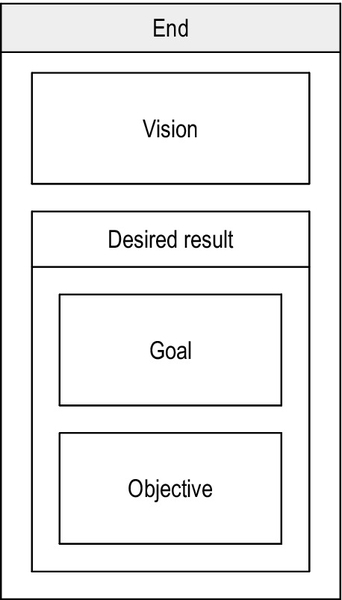

Figure 5.2 shows an overview of the topmost elements of BMM.

End

The end area is divided into vision and the desired results, which in turn, are subdivided into goals and objectives.

Means

The means area is subdivided into mission, course of action, and directives. The course of action is split into strategy and tactic, and directives into business policies and business rules.

Influencers

The influencers are distinguished by external and internal influencers with reference to the enterprise.

External Information

The external information1 comprises organization units, business processes, and business rules. All three information concepts are only referenced here in the BMM and described separately in other standards of OMG:

• Organization Structure Metamodel (OSM)2

• Business Process Definition Metamodel (BPDM)

• Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Rules (SBVR)

Non-OMG Standards Are Permitted Too

Incidentally, all of these are also OMG standards whose usage is not expressly mandatory, but helpful at best. These referenced standards are therefore representative for any descriptive form on these topics. You could just as well describe your business processes with eEPC3 instead of using BPMN.

5.1.2 Scalability of BMM

Decomposable Areas

A business model can possibly become very comprehensive. BMM therefore explicitly supports the scalability of very large descriptions in the following three areas:

• Course of action

• Business policy

The elements of these areas can be broken down into subelements using decomposition. For example, you can decompose a goal into subordinate goals, which are then included in the superordinate goal.

5.2 The Enterprise's End

The end area describes the purpose of an enterprise, that is, the vision and the desired result in the form of goals and objectives (Figure 5.3). The following sections take a closer look at these elements.

5.2.1 Vision

“I spy with my little eye … a vision.” If you apply this typical phrase to an entrepreneur, a vision describes a future image of the enterprise and equally expresses an ultimate, rather impossible, and therefore desirable state, for instance, “We are the leading BPM training enterprise in Europe.”

UML for the Metamodel

The metamodel (Figure 5.4) is noted in the UML language, but don't worry: You don't need a certification in UML (Unified Modeling Language) for this book. We simply explain what you can read from this image.4

The right-hand side of the model indicates: A vision includes any number5 of goals, and every goal amplifies one6 vision at most. That clearly makes sense: The desire to become a leading enterprise may be a really nice thing. However, you should also be able to derive goals from this desire, which ideally are all based on the same vision.

On the left-hand side (read from left to right) the model states: Every mission can make one vision operative at the most. If you read this relation in the opposite direction, it means: Every vision can be made operative by any number of missions.

Different Meanings of Vision

As mentioned previously, a vision describes a future state of the enterprise. But watch out: In everyday language, the word “vision” is also used to describe desirable states outside the enterprise. You certainly know the following:

•Our vision is a world where everyone can be connected.

Nokia

•A PC on every desk in every home.

Microsoft

These are not visions within the meaning of BMM because the BMM vision is supposed to describe an internal view, in other words, it is supposed to refer to the enterprise and not its environment. This car manufacturer, however, got it right:

Good Example of Vision

Become the world's leading consumer company for automotive products and services.

Ford

5.2.2 Goals and Objectives

Goals Should be Measurable

One single neat image of the future would be too abstract. That is why it is reflected in multiple goals in real life. A goal elaborates on the vision, in other words, it describes a long-term goal that must be achieved to amplify the vision, for instance, “Our customers attest that we have very high BPM competency.” Hmm… shouldn't goals be measurable? Right. Something's missing here (Figure 5.5):

Objectives Quantify Goals

BMM also entails objectives in addition to goals. Every goal can have any number of objectives. An objective has no direct reference to the vision; instead, it can quantify any number of goals—it makes them measurable. Accordingly, an objective is a very concrete, achievable statement with measure of performance, for instance, “At the end of next year, 80% of our regular customers evaluate our BPM competency with 9 or better on a scale of 10.”

5.2.3 Desired Result

Both goals and objectives describe—speaking abstractly—some kind of desired result. This term is superordinate of any form of goal or objective, so to speak (Figure 5.6):

“Some kind of” Superordinate

In the diagram, this is indicated with the special form of the arrow, an unfilled triangle, which points from the concrete term to the more abstract superordinate (to be read as “is some kind of” in the direction of the arrow, that is, “a goal is some kind of desired result”).

Every desired result of the enterprise (no matter whether it is a goal or objective) can be supported by any number of courses of action. Courses of action include strategies and tactics from the means area, which we'll discuss in the following.

Remember: The end of a business comprises the vision and the desired results in the form of goals and objectives. All of these elements describe a more or less concrete state which the enterprise wants to achieve sometime in the future. Now you know why this BMM area is called end.

5.3 Means to an End

There's a great quote of Joel Barker, a book author, consultant, and futurist, that emphasizes the significance of the means area:

Passing the Time

Vision without action is a dream. Action without vision is simply passing the time. Action with vision is making a positive difference.

In other words: Visions and goals always entail the means required to implement them. Means can thus be anything that can be used to achieve goals.

Means mainly consist of three elements (Figure 5.7):

• Missions as the counterpart to vision

• Courses of action as the counterpart to desired results

• Directives

It should also be noted that the procedures in an enterprise are implemented through business processes to achieve the mission. Moreover, tactics implement strategies, so they are more concrete than the strategic consideration of means.

Separation of Concerns

In BMM, the means of the enterprise are deliberately described independent of the end. This concept is referred to as separation of concerns and considers that means can change while the goals remain the same. This makes sense.

5.3.1 Mission

A mission describes what an enterprise does to achieve a vision (Figure 5.8):

Mission Makes Vision Operative

A mission makes an associated vision operative in the first place. There can be any number of missions for a vision. Even if Joel Barker, whom we quoted previously, has something different in mind: BMM allows for a vision without missions and also missions without a vision.

Mission Statement

Every mission statement consists of three elements:

• An action in the form of a verb, for instance, offers

• A product or service, for instance, training

• A customer or market, for instance, D.A.CH area7

An example for a mission statement would be: “We offer BPM trainings for enterprises and individuals in D.A.CH.”

Wording Pattern

Unlike the elements from the end area, the elements from the means area don't describe a state (indicated with auxiliary verbs like “be” or “can”), but a measure. It is therefore common to word missions according to the pattern “We < make>…”

5.3.2 Strategy and Tactic

From Section 5.2.3, you already know that a desired result, that is, a goal or objective, can be supported by any number of courses of action. These courses of action include strategies and tactics.

So you can say that every strategy and every tactic is some kind of course of action and, as such, can support any desired results (Figure 5.9).

Strategy versus Tactic

What exactly is the difference between strategy and tactic? The model indicates that a tactic implements any number of strategies. From this, you can accurately conclude that a tactic already describes a very concrete action, while a strategy is still vague.

Strategies Channel Efforts

A strategy, in turn, can be implemented by any number of tactics. BMM considers the strategy as part of the mission's implementation plan to achieve the goals. The fine print says (please remember): Strategy channels efforts towards goals. Let this sentence melt in your mouth, it is very interesting. With this sentence, BMM places the strategy from the means area on the same level as the goal from the end area. In fact, it even requests that a strategy ensures that the “efforts” (this can only be concrete tactics) are aligned with the goals. This also makes sense.

Let's take the following example:

• Goal: “Our customers attest a very high BPM competency.”

• Mission: “We offer BPM trainings for enterprises and individuals in D.A.CH.”

Strategy Examples

Which means that are suitable for the mission are necessary to achieve this goal? With the following strategies, for example:

• Strategy 1: “We increasingly publish in the BPM area.”

• Strategy 2: “We cooperate with an equally renowned Swiss training enterprise in the BPM area.”

We don't know for sure whether these strategies really lead to the desired result. But this gives the direction until you decide on other strategies (i.e., change the means).

Tactics for the first strategy could be the following, for example:

• Tactics 2: “Andrea creates webinars and Web Based Trainings for the OCEB2 certification.”

• Tactics 3: “Tim and Christian write an article on OCEB2 for a professional journal.”

• Tactics 4: “Kim offers preparatory courses on OCEB2 certification at the OOP conference.”

You can see that this is not as unrealistic as it first seemed.

5.3.3 Business Principles and Business Rules

And because our daily working life doesn't have enough trend-setting elements already, there are another two to be considered. The third main element of the means area involves the directive.

Directives, Business Policies, or Business Rules

While the two courses of action, strategy and tactic, only make statements on what is done, a directive describes how it is done. Every directive can govern any number of courses of action and support any number of desired results (goals or objectives). A directive is either a business policy or a business rule (Figure 5.10).

Enforcement Level

BMM provides an enforcement level for every business rule. This enforcement level can make a statement on the enforcement of a business rule. The enforcement level can have two characteristics:

• Strict—The business rule must be adhered to. It becomes an organizational procedure (which may be labor law-relevant).

• Guideline—The business rule should be adhered to, but deviations may occur in justified exceptions.

Examples for Directives

To continue the previous example, the following would be suitable examples:

• Business directive: “Our ambition is always to exceed the expectations of every customer. Every customer should be positively surprised at least once, ideally with every order.”

• Business rule (guideline): “Graphics for publications and training presentations should be created using Visio.”

• Business rule (strict): “Employees, who are being prevented from coming to work, must immediately notify the management stating the reasons and the estimated duration.”8

5.4 Influencer

Somehow, everything in this world has some kind of influence on something. Tonight's weather forecast will have an influence on the clothes you are going to wear tomorrow. The book which you are reading right now will have some (hopefully positive) influence on your everyday work. As you can see, we are gradually entering a philosophical level here.

Enterprises Subject to Influences

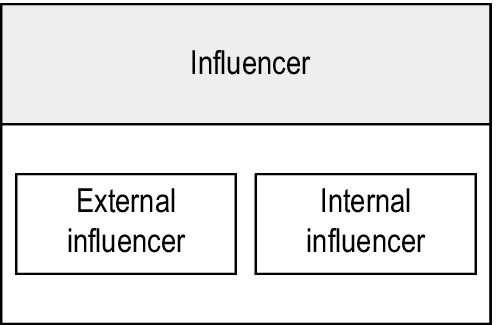

BMM even considers these topics which are rather part of the humanities. It defines an influencer area which describes to which influencers the enterprise is exposed, for instance, current trends in the market, activities by competitors, or the employees' attitude. Influencers can be external influencers or internal influencers (Figure 5.11).

Influences Justify the End and Means

Naming the influences helps you to understand how and why the end and means of the enterprise have come about. According to this, influencers are concrete events that occurred at a specific point in time, for example, the rapid increase in the sales of green power supply products after the nuclear disaster of Fukushima. But influences can also involve facts or even habits (unwritten laws), for instance, “managers are always recruited within the organization.” The format of an influence is less important; it is more essential that the influence is relevant for setting the goal, and/or that it has the means to achieve the goal.

Initially, influencers are just there—until someone makes an assessment9 on how they influence the end and means (Figure 5.12).

Influencers Are Always Neutral

It is therefore important that the influencer itself is described neutrally and not subject to assessment. As you can see in the previous model, for every influencer there can be any number of assessments which are considered independent of the influencer.

5.4.1 SWOT Assessment

The BMM's standard procedure available for such matters is an excellent example for such an assessment: the SWOT analysis, which was already presented in Section 2.1.8.

Evaluate Nuclear Disaster

For this purpose, you select an (external or internal) influencer—let's say “Nuclear Disaster of Fukushima”—and assess its impact on the enterprise. For many enterprises, the impact may pose a threat; others conclude that this event doesn't have any impact on their business area, or that provides a great opportunity. The assessment may lead to a new goal for which you must find a suitable means for implementation. The next section provides more information on this.

5.4.2 External and Internal Influencers

An enterprise is exposed to influences from the outside or from within. For this reason, BMM makes a distinction between external and internal influencers. Every influencer can be assigned to different categories. The BMM has already defined default categories for external and internal influencers. You can add further categories if you want to (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1

Default Categories for External Influencers

| Competitors | Environment |

| Customers | Regulation, laws |

| Partners | Technologies |

| Vendors |

An example for an external influencer (category: competitors) would be: “Two competitors have merged and are therefore larger than the enterprise considered.” (Table 5.2)

Table 5.2

Default Categories for Internal Influencers

| Assumption | Point of issue |

| Enterprise value (implicit, explicit) | (Management) privilege |

| Habit | Resource, supplies |

| Infrastructure |

A concrete example for an internal influencer (category: privilege) would be: “The management has decided that, in the next three years, expansion in Switzerland has priority over other countries.”

5.5 Assessments

Have you ever been to an assessment center? If not, imagine a row of judges (maybe from sports) who hold up their marks after you've given your presentation. They “assess” you.

Assessments Assess Influencers

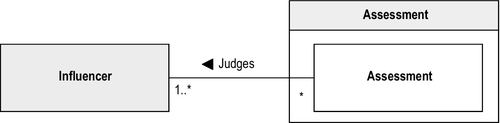

This is exactly what happens to an influencer, which is a neutral element initially. The influencer is not evaluated until the assessment, more precisely: It judges the impacts of the influencer on the end or the means of the enterprise. The overview of this separate area is rather plain; it only contains one single element (Figure 5.13):

Assessments as the Connecting Link

This area is not particularly comprehensive; however, the assessment establishes the logical link between the influencers and the end and means of the enterprise. The metamodel illustrates as follows.

An assessment can judge multiple influencers (but at least one). This makes sense because otherwise, you wouldn't know what the assessment refers to. In this context, it is insignificant whether the influencer is external or internal (Figure 5.14).

It is possible that the assessment affects achievement of any elements from the end area, for instance, goals or objectives, or even the vision. In the above model, the term end is used as a superordinate for these elements.

And finally, the assessment can affect the employment of any means, in other words, it can lead to new missions, strategies, tactics, policies, or business rules. Here again, means is to be understood as a superordinate for these things.

SWOT

SWOT assessment—again? Déjà vu? That's right. So that SWOT really haunts you in your dreams, the following illustrates the topic from another perspective.

SWOT as an Assessment Category

Every assessment can be provided with different categories. If you cannot think of anything new, simply use one of the SWOT letters for strength, weakness, opportunity, or threat as the default assessment category—that's what BMM requires.

External influencer = opportunity or threat

Internal influencer = strength or weakness

Typically, there's a context between the type of influencer (external or internal) and the SWOT categorization of an assessment. Although this is self-evident, it is helpful to call attention to this fact: Presumably, you would assess the nuclear disaster neither as a strength nor a weakness, but only as an opportunity or threat. Got the context? Exactly. External influencers are rather categorized as opportunity or threat, while internal influencers are assessed as strengths or weaknesses.

5.6 Organization Unit

Imagine that you (for whatever reason) modeled an enterprise's vision, the most essential goals and objectives such as missions, strategies, tactics, business policies, business rules, influencers, and even their assessments, and everything just looks great: Well, congratulations!

But what's the use of this model if you don't specify who is to execute the tactics and business processes or comply with the business rules? This directly takes us to the department or the general organization unit (Figure 5.15).

The organization units are part of the external information, just like business processes and business rules. Well, at least from the BMM perspective. Here, OMG clearly delimits the BMM from other standards and, in the BMM, provides for placeholders for other standard concepts.

Logical Links

So it is the task of another standard to describe organization units. But BMM defines how organization units should be linked with the BMM elements. Accordingly, concrete logical links of BMM and organization units are as follows. An organization unit

• Establishes means,

• Recognizes influencers,

• Makes assessments,

• Defines strategies, and

• Is responsible for business processes.

Digression Zachman Framework

Within the scope of business process management, the term Enterprise Architecture Management (EAM) is frequently used. This involves the enterprise's business processes, as well as the consideration and administration of human resources and infrastructure (buildings, inventory, machinery, and IT) of an enterprise. The originator of EAM is John Zachman, who developed the Zachman Framework for documenting and managing enterprise architectures in 1987. You can find more information at http://www.zachman.com/about-the-zachman-framework. The Zachman Framework provides a holistic view of an enterprise and primarily integrates organizational and information-related aspects. The different perspectives (e.g., what, how, and why) are compared with different levels of detail and roles within the enterprise. The BMM we just considered is used as a business plan, for example, in the “why” perspective, that is, the motivation for a process, and at the level of the conceptual enterprise model. Moreover, the “who” column of the framework considers the various organization units of an enterprise. The “how” column (described by business processes) establishes the connection between end and means.

5.7 Levels of Abstraction in Modeling

Have you ever been to the Miniatur Wunderland in Hamburg? If not, you may have read about it in various travel guides. There, various scenarios and gigantic landscapes are recreated in model railroad format across multiple floors—and everything is built with an absolutely unbelievable love for detail. This is a great example for a model as a copy of reality.

BMM is also about models—enterprise models. This being the case, it is obvious that the OCEB2 certification program also deals with the rather general topic of abstraction levels in modeling.

5.7.1 The Art of Abstraction

In the Miniatur Wunderland, you don't see all the details of reality, which is a good thing. This is because abstractions are necessary to structure complex situations and reduce them to a manageable and comprehensible dimension. Otherwise, you would be overwhelmed by the flood of information.

Comprehensive situations are ideally mapped at different levels of abstraction, where each abstraction level should represent a meaningful view of reality so that it can be communicated easily. Unfortunately, you cannot measure the degree of abstraction, but human beings are able to compare two elements and tell which one is more concrete than the other. This is basically enough to ensure, to a certain extent, that elements of the same degree of abstraction are at the same level of abstraction.

In Figure 5.16, an example of levels of abstraction would be the levels of business processes, business workflows, and business scenarios. A business process consists of multiple business workflows and a scenario is a concrete business workflow.

So if Sam Shark calls SpeedyCar to rent a car for the next day, this is a business scenario. The business workflow, however, describes in general10 how a new car booking is made. A business process additionally describes business workflows, such as changes, cancelations, and billing of car bookings.

Getting Concrete at an Abstract Level

The more you abstract (go to higher levels), the more details you must omit. And still the abstraction is to enable added value, that is, it only makes sense if it is still concrete enough. In other words (if you are still looking for quotes): “Good modeling is the art of getting concrete at an abstract level.” (Tim Weilkiens [39]).

Abstract Models Should Look Nice

At the highest levels of abstraction, the added value mainly consists of the overall view. This involves those nice maps which can be found in many enterprises and are often used to get started. Even if such an “abstract” overviews appear rather trivial: Their development definitely wasn't. And as a structural graphic, a highly abstract model may look neat and tidy.

5.7.2 Static and Dynamic Models

Whatever topic you select: Start modeling at an abstraction level where modeling seems to be easy. You can use this as the basis for detailing.

Skeleton = Static

The outcome of this decomposition also depends on the type of model. Static models map a specific structure. The human skeleton is a good example here: head, upper limbs, body, and lower limbs. The lower limbs include upper leg, lower leg, foot, and so on. As you can see, you can easily dissect a skeleton—proverbially.

In the dynamic models, it's not that easy because their elements are structured in a network and not in a hierarchy like in business workflows, for example. In this respect, the abstraction levels fulfill an important task, also for the conceptual identification of an element.

Processes = Dynamic

Business modeling mainly creates static models, while the modeling of business processes primarily focuses on dynamic models. Particularly if it involves cross-organizational aspects, then the dynamics are much more interesting than the structural context. Business process models therefore, mainly illustrate activities of people, decisions, and the collaboration of departments.

5.7.3 Systems Thinking

In the upper levels of abstraction, you are quickly confronted with the topic of systems thinking. Systems thinking means to consider the system as a whole. All parts, their connections, and interactions are taken into account. The traditional analysis (Greek analusis = a breaking up) breaks up a system into its individual parts and runs an isolated inspection. Systems thinking helps to master complexity.

Google Earth

You surely have used Google Earth to search for your home, right? Starting in space, you first zoom to your continent, then to your country, and so on until you can see your house (and find out, to your own horror that the recording was made last Sunday, because you can see the car of your in-laws).

Everything is a System

What's the reason for this excursion? It wants to illustrate: Everything is a system.11 When you hear the term system, you quickly think of technical systems. But that is not what is meant here. Everything that you can perceive as a unit of structures and interactive elements constitutes a system. The earth is a system. The United States is a system. And even your family in your house is sort of a system.

In terms of business process management, the systems thinking constitutes the topmost level of abstraction. The enterprise is a system, and the processes are its elements, which in turn, include business workflows and these again are business scenarios.

Organization units, resources, and other things are also integral parts. Systems thinking is supposed to consider all elements and their interactions.

5.7.4 Syntax, Notation, and Semantics

In order to model systems, you require a modeling language consisting of syntax (vocabulary of the language, including notation and grammar, i.e., including rules on how to use the vocabulary) and semantics (the coordinate and uniform meaning).

The syntax can be subdivided into concrete and abstract syntax:

• The concrete syntax is the (usually graphical) visualization of vocabulary, which is also referred to as notation. For example, you can consider whether you want to illustrate the vision as an eye, and a goal as the bull's eye of a target.

• The abstract syntax, by contrast, involves a set of defined vocabulary (vision, goal, and so on) and its structural context. In BMM, this abstract syntax is illustrated as UML models.

Abstract and concrete syntax ultimately specify how an enterprise model can be described with concrete elements, for example, the defined vision and concrete goals and objectives. The BMM specification therefore contains a model of an enterprise model (hence the root word “meta”). As mentioned initially, BMM does not define any notation (concrete syntax), but leaves it up to you, dear reader, to select the appropriate notations (Figure 5.17).

Developing Your Own BMM Notation

So if you want to use BMM in real life, you must design your own graphical notation (sign language). Compared with pure text documentations, graphical models have the following benefits:

• Graphics can be understood and memorized faster.

• A specific perspective of reality can be presented in a targeted manner.

• An existing metamodel already provides a meaning for the concrete model, without having to document it explicitly once again.

Semantics

Semantics describes the meaning and the use of the model element if required.

BMM writes the following about vision: “A Vision describes the future state of the enterprise, without regard to how it is to be achieved […].” This meaning helps us to find the right level of abstraction.

Precisely because a model is always an abstraction, it should always be unique. Well-defined syntax and semantics provide support here. The more uniquely you define the abstract syntax, notation, and semantics, the sooner different users obtain a common, and, above all, holistic understanding of a model's meaning. Therefore, specifications, such as BMM, try to illustrate situations with many graphical UML models and combine them skillfully with natural language.

5.8 Sample Questions

Here you can test your knowledge on the business modeling topic. Have fun!

You can find the correct answers in Section 8.4, Table A.4.

1. A car rental company plans to open new branches in other countries. Which BMM element must be used to describe that statement?

(b) Mission

(c) Strategy

(d) Vision

2. A car rental company plans to double the number of customers within the next 5 years. Which BMM element must be used to describe that statement?

(b) Vision

(c) Strategy

(d) Objective

3. Which aspect best fits the systems thinking discipline?

(a) Product development and operation

(b) Abstraction and complexity

(c) Communication and presentation

(d) Simulation and optimization

4. What is most important about the semantics of a model element?

(b) The meaning is commonly accepted.

(c) The meaning is concrete.

(d) The meaning is abstract.

5. Which are elements of a modeling language?

(a) Abstract syntax, concrete syntax, semantics

(b) Notation, semantics

(c) Vocabulary, grammar, relationships

(d) Syntax, concrete semantics, notation

6. The annual report of a car rental company shows that there is an increasing demand for luxury cars. Which BMM element must be used to describe that statement?

(b) Assessment

(c) Influencer

(d) Opportunity

7. For the first time a car rental company is fair according to slight car damages, like minor scratches. Which BMM element must be used to describe that statement?

(b) Strategy

(c) Tactic

(d) Mission

8. What are top-level elements of the end area?

(a) Mission, course of action, directive

(b) Vision, desired result

(c) Business rules, business processes, organization unit

(d) Assessment, influencer

9. How could a competitor be described in BMM?

(b) Actor

(c) Influencer

(d) Market

10. Which concept does BMM use to enable large models?

(b) Decomposition

(c) Abstraction

(d) Packaging

11. What is a set of categories for an assessment?

(b) External, internal

(c) End, means

(d) Rule, policy, procedure