Basic Principles of Business Management

Abstract

Appropriate communication with people from business departments is an essential success factor for BPM experts. Therefore it is necessary to establish a basic understanding of the vocabulary of concepts that they use. This chapter provides a rough overview of topics like management competencies, business strategy, market segmentation, SWOT analysis, value chains, cost types, and planning techniques.

This chapter explores the basic principles of business management. The term business is part of the name of the OCEB certification. And as the structure of the certification program already suggests, it is particularly important to the persons behind this idea to establish a common language between experts and IT employees. This is reason enough to cover the basics of business management and get acquainted with some basic terminology and concepts of this economic science, from the business process perspective. The chapter explores business functions, markets, and strategies; marketing, added value, and project management; costs, efforts, and key figures; and analysis methods. Developing strategies in line with market requirements entails some strategic deliberations and careful analyses of the market environment as well as a straightforward consideration of a company's strengths and weaknesses. A common, rather business-related definition is that marketing describes the orientation of an enterprise in the market. Value chain is one of the basic competencies of an expert in business process management because business process analyses and optimizations are typically handled in projects. The basic knowledge of business management also includes costs, efforts, and key figures. One must be able to distinguish between fixed, variable, and overhead costs. Besides the general distinction of cost types, there are numerous financial key figures out of which only a few are significant within the scope of the OCEB certification.

Keywords

Management competencies; Business strategy; Porter's Five Forces; STEP analysis; Market segmentation; SWOT analysis; Value chain; Break-even analysis; Crossover analysis; Network plan

Manager: The man who knows exactly what he cannot do, and finds the right persons to do it for him.

Philip Rosenthal

The term business is already included in the name of the OCEB2 certification. And as the structure of the certification program already suggests, it is particularly important to the persons behind this idea to establish a common language between experts and IT employees. This is reason enough to deal with the basics of business management and get acquainted with some basic terminology and concepts of this economic science—at least from the business process perspective.1

2.1 Business Functions, Markets, and Strategies

Developing strategies in line with market requirements is not as easy as it seems. This entails some strategic deliberations and careful investigations of the market environment, as well as a straightforward consideration of your own strengths and weaknesses.

2.1.1 Typical Business Functions

Usually, an enterprise has a lot to do to accomplish its purpose. If you very roughly group these tasks, you obtain business functions that are very similar in most enterprises (Figure 2.1).

Business Function versus Department

Even if you have this impression: Business functions are not departments because a department can execute multiple functions. In enterprises with traditional organization, however, it is often common practice to establish a department for more or less one particular function. Therefore, department and function are often used synonymously. In modern and rather process-oriented enterprises, however, a function is frequently mapped onto multiple organization units.

Core and Support Functions

Depending on whether a business function directly serves the object of the enterprise or not, you can distinguish core functions or support functions.

Reflect on the typical enterprise functions of Figure 2.1 for a while and particularly memorize the terms of the functions and the tasks associated with them.

Human Resources

Special attention should be paid to human resources. Apart from the vision of a fully electronic enterprise where only robots work,2 the employees (and who should know that better than you, dear reader) are the ones that enable an enterprise in the first place to implement its strategies. Nevertheless, human resources are usually considered as a support function.

2.1.2 Managers and Their Competencies

What does a manager actually do all day long? Of course, OCEB2s cannot answer this question in your context, but they know some basic terms for this.

Manager Delegate

So it's not important what is actually organized. The main thing is that others do it.

If you now look at a whole enterprise, another term is often used in literature:

Seven Manager Competencies

A manager requires certain key competencies to let wondrous things happen by others. To be more precise, a manager requires seven competencies:

• Planning

• Decision-making

• Delegation

• Support

• Communication

• Controlling

2.1.3 Business Strategies

Surely, you've played chess before. The goal is kind of clear: win. But what's the best strategy? As you know, there are countless possibilities. Once you've decided on a strategy, you move your chessmen in compliance with this strategy. You do so until you're convinced that another strategy would be more clever.

The Strategy is the Means to an End

This similarly applies to the business strategy. It is always a means to the business end and must match the enterprise's mission (Chapter 5 distinguishes the terms, vision, mission, goal, strategy, and tactic in more detail).

The business strategy, as long as it is valid, defines the direction into which an organization develops. It thus provides a framework for decisions, similar to guardrails on the highway that ensure that all cars are driving in the same direction, at least between two exits.

To yield an advantage within the changing market environment, it is occasionally necessary to change the strategy in order to newly configure the organization's resources.

As soon as the enterprise's strategy has been defined, you can derive various factors (e.g., personnel and marketing strategy, goals). The enterprise's personnel require goals so that they can align their actions and consider them in the overall context (business strategy). Actively defined goals motivate the people, and the consolidation of contradictory goals across various departments to create similarities.

2.1.4 Strategy Development

If a chess player wants to decide on a strategy, he surely doesn't do so without due consideration. Instead, he will gather some information, particularly about his opponent. Presumably, he'll take a look at the games of chess he already played to determine a pattern and detect strengths and weaknesses.

Business Strategy Steps

That's what an enterprise basically does to determine its business strategy:

• First, it analyzes the market environment. (Which forces affect the market? Which factors influence the strategy selection?)

• Then, it divides the market into segments theoretically. (Which buyer groups exist? Where are any market niches?)

• Then, the enterprise analyzes its strengths and weaknesses, if required, for each market segment separately.

• This forms the basis for setting objectives and planning the measures to be taken.

Signs like failures, times absent, and fluctuation or large amounts of overtime indicate that the enterprise's personnel management must be adapted. In the best case, this is done based on the strategy. After the strategy has been developed, you can and should plan the personnel deployment by analyzing various aspects:

• Strategic vision of the enterprise.

• Short-term and long-term goals.

• Changes in the market that impact the enterprise.

• Requirements with regard to personnel based on the strategic vision.

• Possible opposition in the organization.

Beyond personnel management, it makes sense to break down the enterprise strategy into goals. These goals (or targeted conditions) should reflect the enterprise strategy and support orientation and optimization when assigned to individual business processes.

After the internal view, the following discusses the market analysis, that is, if you continue reading you get to know some customary techniques to implement these steps.

2.1.5 Porters Five Forces

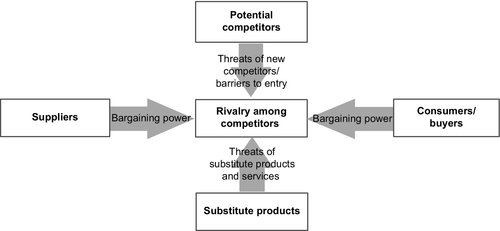

Michael E. Porter is one of the leading economists in the area of strategic management and, for many years, he has occupied himself with how enterprises can gain a competitive edge. He developed the Porter's Five Forces framework that supports an enterprise in selecting a suitable strategy to gain a competitive edge.

Market Structure

The idea is simple: The enterprise's success significantly depends on the competitive strategy which is mainly determined by the structure of the market in which the enterprise is active. The market structure of an industry can be attractive or not. But which forces impact this industry structure and thus the attractiveness of a market? (Figure 2.2).

Porter's Five Forces

The following five forces exist:

• If an enterprise is already in the market: threats of new competitors, or if the enterprise wants to enter a new market: barriers to entry,

• Bargaining power of consumers/buyers,

• Threats of substitute products or services, and

• Bargaining power of suppliers.

It is obvious that enterprises should attempt to be active in an industry whose market structure is exposed to as few threats from these forces as possible.

2.1.6 STEP Analysis

STEP = PEST

Another option to analyze and assess the attractiveness of a market is to use the STEP analysis (Figure 2.3). The acronym consists of the initial letters of the market environment factors to be considered (this technique is also referred to as PEST analysis3).

Ready-Made System

This ready-made system simply provides references for considering the opportunities and threats of a market. For example, an enterprise can consider which threats it is exposed to with regard to the trend of interest rates. Likewise, there can be opportunities, for instance, if the enterprise can manufacture products that are subsidized.

2.1.7 Market Segmentation

Isemarkt in Hamburg

Have you ever been to the Isemarkt in the German Hanseatic City of Hamburg? This is a rather big weekly market that spreads almost half a mile below the city's metro rails. Various market segments, such as jewelry stands, vegetable stands, and so on, exist there. The attractiveness of the market doesn't necessarily depend on the whole market, but on the competitive situation in the respective segment.4

This does not only apply to weekly markets. For this reason, a complete market for products and services is usually subdivided into small, manageable segments. The heterogeneous total quantity of market participants is divided into homogeneous target groups which market policy efforts should focus on (Figure 2.4).

Division Strategies for Market Segments

There are various division strategies for the segmentation of a market:

• One-dimensional segmentation, for instance, by income classes,

• Multidimensional segmentation, for instance, by countries and income classes, and

• Complete segmentation where each customer is handled individually.

Market Niches

Because not every segment entails the same profitability, market niches can arise. They provide an opportunity to gain the leadership in the market segment.

2.1.8 SWOT Analysis

The previously described techniques (Porter's Five Forces, STEP analysis, and market segmentation) help to analyze the market environment externally, that is, the environment outside an enterprise. It makes you realize which opportunities and threats exist with regard to a market or market segment.

Derive Strengths and Weaknesses

But not only is the market environment of an enterprise of interest, but also the enterprise itself. It has specific characteristics (for instance, quality of products compared to competitors, qualification of employees, level of awareness) with which it acts within the market. Within the scope of an internal analysis, these characteristics can be used to derive strengths and weaknesses of the enterprise, with regard to a market or market segment.

The collected results of the external and internal analysis can be initially presented as an overview using a SWOT matrix (Figure 2.5).

This summarizing comparison often helps you to think about how you can leverage strengths and decrease weaknesses in order to pursue opportunities in a targeted manner and avert threats.

Four Combinations

When you compare the results of the internal analysis with the result of the external analysis, you obtain four combinations that form a holistic business strategy:

• Strengths + opportunities: Pursue new opportunities that blend well with the strengths of the enterprise.

• Strengths + threats: Leverage strengths to avert threats.

• Weaknesses + opportunities: Decrease weaknesses to leverage new opportunities.

• Weaknesses + threats: Develop defense strategies so that weaknesses don't result in threats.

Because each enterprise has both strengths and weaknesses, and each market environment involves both opportunities and threats, you should always take all of these combinations into consideration.

2.2 Marketing, Added Value, and Project Management

Marketing is of high significance in virtually every enterprise because the products and services must be delivered to the customer, after all.

Marketing Designs the Value Chain

But why is marketing important for an expert in business process management? One of the most important business process types is the value chain. It's one of marketing's tasks to design the value chain. Therefore, just like basic knowledge of project management, understanding this term is one of the basic competencies of a BPM expert, because business process analyses and business process optimizations are typically handled in projects.

2.2.1 Marketing

The term marketing is not as clear as it seems. A good business process management expert should therefore know different uses of this term so that he can distinguish them in heated discussions and ask how others use this term.

A common, rather business-related definition is that marketing describes the orientation of an enterprise in the market:

The subsequent advanced, and rather economical, definition understands marketing as a global event and therefore focuses not only on the individual enterprise, but also the interactions in the markets:

Forms of Marketing

However you interpret marketing, you can run “marketing” either reactively or proactively. Consequently, you can distinguish two different forms of marketing (Figure 2.6).

Reactive and Proactive

An enterprise uses reactive marketing if it (only) reacts to what others do and imitates them. Proactive marketing, by contrast, is a philosophy which ensures that resources are deployed in such a way that the requests, requirements, and needs of customers take center stage in the enterprise's activity.

2.2.2 Process Elements of Marketing

If you understand marketing as a business process (Chapter 3), this inevitably raises the question of which elements or activities this process generally involves.

Marketing ≠ Brochures and Trade Fairs

Marketing is by no means limited to designing brochures and attending trade fairs. This understanding involves a very manifold and continuous process that ultimately touches most enterprise areas (Figure 2.7).

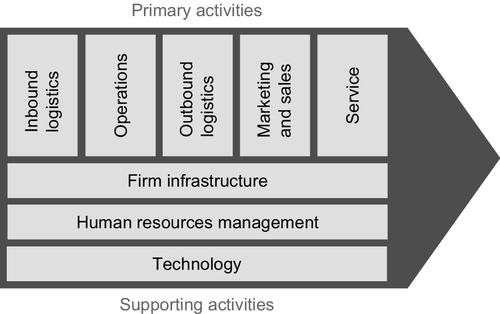

2.2.3 Value Chain

One term that often comes up in the context of marketing and business processes is value chain. Michael E. Porter—whom you already know from Figure 2.2—wrote the following on this topic [28]:

Figure 2.8 shows a typical value chain.

Primary and Supporting Processes

Most notations of value chains typically use arrows to distinguish between core processes (also primary processes or activities) and supporting processes. Let's take a closer look at the eight individual elements of the value chain (inbound and outbound logistics, and so on). They are indeed typical, even if you don't find the processes mentioned there in exactly this form in every enterprise, or if they have other names.

2.2.4 Projects

Many plans in the environment of business process management are handled as projects. It is therefore expected from a BPM expert that he (or she) knows what a project actually is.

What a Project is

Perhaps, you are currently in a project or know from other sources that a project:

• is an undertaking with limited timeframes and budget to deliver several clearly defined results and

• is basically characterized by the uniqueness of conditions in their entirety.

Great! Then we don't have to write this down now. By the time you encounter certification questions on this topic, you will remember: Projects are limited and unique.

2.2.5 Project Management

Well, we've already discussed what management is (remember: Letting things happen by others or “what managers do”). Applied to a project, this means:

At first, this sounds trivial. In reality, of course, this process involves a good deal of different tasks, which can be grouped as shown in Figure 2.9.

In this presentation, project management already starts with the initiation of the project. The project itself does not start until the project charter has been signed. This is followed by planning, executing, and controlling the project. Usually, changes arise from controlling so that the cycle starts all over again. The final step of the project is referred to as closing.

2.3 Efforts and Key Figures

The basic knowledge of business management naturally also includes efforts and key figures.

2.3.1 Cost Types

Fixed, Variable, and Overhead Costs

In the most general sense, you must be able to distinguish at least fixed, variable, and overhead costs.

Do you have a car? Excellent5 Then, car taxes and insurance are the essential fixed costs. They incur independently of the mileage, even if you leave your (licensed) car in garage.

In our car example, these are primarily operating costs, mainly for gas. The more miles you drive, the higher the variable costs are.

If you had an entire car pool to rent instead of a single car, then costs for personnel or garages or, electricity and water cannot be allocated to a car according to the cost-by-cause principle, but must be distributed to all vehicles.6

2.3.2 Financial Key Figures

Besides the general distinction of cost types, there are numerous financial key figures out of which only a few are significant within the scope of the OCEB2 certification.

Working Capital

But how does an enterprise actually know whether it is able to meet its obligations? In principle, it's very simple: It measures the (more or less) available capital.

First, you determine the current assets. Put simply, the assets that are available within a relatively short term. These include, of course, the money on bank accounts and in cash registers, but also stocks, sellable stocks, and receivables.

To calculate the working capital, you simply subtract the current liabilities from the currently available assets. The current liabilities include all debts that must or will be cleared within 1 year. In the best case, an amount that is considerably above zero remains.

Return on Investment

When you make an investment, for instance, when you buy machinery, you want to know how cost-effective this is for the capital invested.

Let's assume that your capital employed is $10 and you use it to generate an earning $3 after a specific period of time, then the Return on Investment (ROI) is 0.3. So each dollar you invest becomes $1.30. According to this, it is good if the ROI is greater than 0.

In this context, it is insignificant if you make such minor investments or investments of billions or consider the entire enterprise itself as an investment.

2.4 Analysis Methods

The financial key figures presented in the previous section are all snapshots without any exceptions, which usually refer to a single scenario, for example, to a specific quantity produced.

Techniques for Decision-Making

Reality, however, constantly provides enterprises with a whole series of options. But which one is the best? Business management offers some well-known techniques for this decision-making in order to make different scenarios assessable.

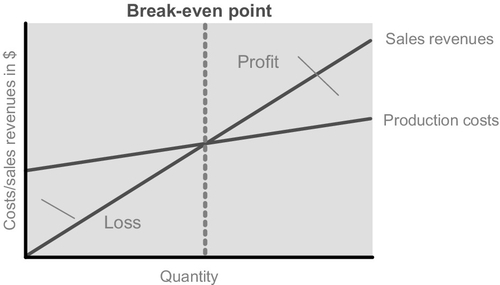

2.4.1 Break-Even Analysis

Let's assume that an enterprise must decide to run production in the United States or abroad. The various national markets have different price and cost structures. In other words, the revenues to be obtained, on the one hand, and the production costs, on the other hand, differ in the markets at choice (Figure 2.10). Which constellation is necessary so that the enterprise chooses the United States?

Break-Even Point

Very simply: It stays if it is more likely to gain profit in the United States than abroad with the same quantity.7 The quantity where the profit zone begins is referred to as break-even point.

Both the gradient and the origin of the straight line typically run differently. While the sales revenues start at the point of origin, production costs already arise, even if not a single unit has been produced yet. Moreover, the sales revenues have a stronger increase than the costs, so that the two straight lines eventually meet at the break-even point. You can calculate this point using the following formula:

If the production costs were identical in both countries, then the enterprise would stay in the country that has a stronger sales revenue line (in other words, the country where higher prices can be reached with identical costs). You can go through the other possible scenarios yourself.

2.4.2 Crossover Analysis

While the break-even analysis enables the assessment of different scenarios with regard to sales revenues and expenses, the crossover analysis uses the same principle to compare different scenarios with regard to fixed and variable costs.

Remember your car? In Section 2.3, we briefly used it to describe the difference between fixed costs (taxes, and so on) and variable costs (costs for gas, and so on).

Porsche is More Expensive than Smart

If you only differentiate by costs and think about whether you want to drive Porsche Cayenne or Smart, then you don't need a crossover analysis. Compared with Smart, Porsche is clearly superior, both with regard to fixed costs and variable costs.

If you want to decide between a diesel-driven and a gasoline-driven car for the same car type, then it's worth calculating the crossover point (Figure 2.11).

Diesel versus Gas

In Figure 2.11, scenario 2 presents the diesel car. Due to higher acquisition costs, the line starts further up on the y-axis, and its lower gas costs cause a lower increase of the line. For the gasoline-driven car, the line starts further down, due to lower acquisition costs, and increases greater as a result of higher gas prices. The two lines intersect at the crossover point.

In business management, the horizontal axis usually involves quantities. In this example, however, we don't use the quantity, but the annual mileage.8

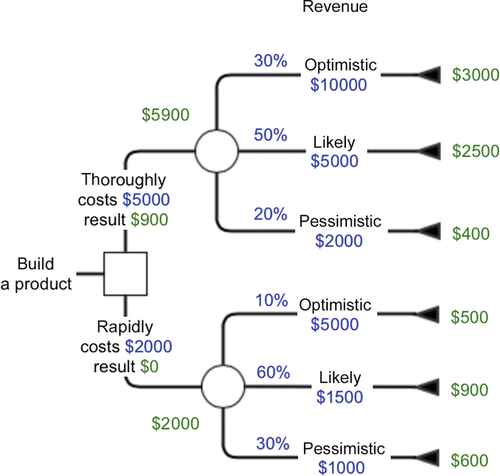

2.4.3 Decision Trees

Sometimes you simply lose track if you have too many options. Then it is useful if you can visualize the various scenarios to be assessed in a decision tree (Figure 2.12).

Study or Earn Money?

The decision tree is somewhat similar to life: You get to a fork in the path and must decide whether to turn left or right (study or earn money?). Then you get to another fork which may lead to more directions (three different job offers). Every fork is connected with probabilities of occurrence. At the end, you reach the leaves, and you can assess each path by considering the probabilities.

2.4.4 Scheduling and Resource Planning

Scheduling and resource planning enables you to estimate whether projects can be completed within the timeframe required and whether the required resources are actually available.

One technique available in this context is the network plan where a project is split into individual tasks (A, B, C…), which are then put into sequences (Figure 2.13). Some tasks are independent of each other and can be performed simultaneously. For each task you can specify the earliest and latest start time, their minimum runtime, and the earliest and latest stop time. This information can be used to determine the tasks that have a time buffer and which tasks are on the critical path. If there are any delays on this critical path, this results in delays in the overall project.

2.5 Sample Questions

Here you can test your knowledge on the Basic Principles of Business Management topic. Have fun!

You can find the correct answers in Section 8.4, Table A.1.

1. Which of the following items describe the project management process?

(a) Negotiate, estimate, budget, report

(b) Initiation, planning, executing, controlling, closing

(c) Cost, time, quality, scope

(d) Plan, do, act, fix

2. According to the book “MBA in a day”: which definition describes the marketing process?

(a) Marketing is a process which ensures that brochures and the like are being manufactured in high quality and which arranges the stand at a trade fair.

(b) Marketing is a synonym for distribution. Therefore its goal is to bring new products and services to the market and sell them with the highest possible price.

(c) Marketing is a social and managerial process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating, offering, and exchanging products of value with others.

(d) Marketing is the systematization of generating leads (by taking out adverts on different media channels), evaluating each lead and then routing them to the sales department.

3. Which are elements of an effective marketing strategy?

(a) Initiation, planning, executing, controlling, closing

(b) Market segmentation, strategy development, market research, pricing, placement, and value chain

(c) Inbound logistics, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, service

(d) Potential competitors, suppliers, consumers, substitute products, and rivalry among competitors

4. What is a value chain?

(a) It includes inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, service, firm infrastructure, human resources management, and technology.

(b) It creates value to the market by considering demographic, technological, economic, and political factors.

(c) It is a chain of actions that measure the increasing value of an economic good being manufactured.

(d) The value chain describes the performance of a set of company shares. Common examples of value chains are Dow Jones and DAX.

5. What is the break-even point?

(a) A special item on a Balanced Score Card (BSC)

(b) The point at which production costs are equal to the sales revenues

(c) The point at which a company becomes insolvent

(d) The point at which variable costs overtakes the overhead costs

6. Which business function is a support function?

(b) Human resources

(c) Accounting

(d) Project management

7. Which statement about the working capital is correct?

(a) It is the company's current assets that are bearing interest.

(b) It is the company's liabilities divided by its current assets.

(c) It is the limit of the amount that can be withdrawn at a cash point within 1 day.

(d) It describes the company's ability to pay its current obligations.

8. Which are the main management skills?

(a) Communication, research, and pricing

(b) Planning, executing, and closing

(c) Goal-setting, planning, and controlling

(d) Analyzing, calculating, and facility managing

9. What is the main goal of the business function “Finance”?

(a) To manage financial instruments in order to keep the competitors breathless

(b) To ensure that the company has enough money it needs to keep the business running

(c) To be informed where the money comes from and where it goes to

(d) To decide on expenses, be responsible for mismanagement and collect bonuses