Questioning: Improve Your Skills

24 What Are the Attributes of a Person Who Asks Good Questions?

In his book on cross-examination, Francis Wellman, one of the nineteenth century’s most well-recognized attorneys, discussed the attributes of a good cross-examiner. Although observed more than one hundred years ago, these attributes reflect an ideal that we can apply to managers today. They share the status of “professional questioner” along with attorneys.

Wellman’s attributes have been adapted specifically for managers of today and for anyone who relies on avenues of inquiry to excel at their job:

• Attention to following up. This attribute is vital for managers.

• Ability to judge character. This attribute enables the manager to choose effective questions that fit the respondents.

• Ability to act with force. The manager must know what to do with the answer and then have the ability and commitment to do it.

• Instinct to discover weaknesses. This attribute is an asset in all processes that require the use of questions.

• Appreciation of motive. Every business setting is accompanied by a set of motives for the business, management, and each participant.

• Good intuition/instincts and business acumen. This attribute is actually a set of attributes that combine to provide insight into what needs to be asked.

• Clear perception. This attribute enables the questioner to maintain focus on what is important.

• Knowledge. To a person skilled in asking questions, this attribute can mean knowing what is not known.

• Ingenuity. Business processes are unscripted interactions that require flexibility of mind and purpose.

• Patience. All minds are not equally facile, so appropriate time must often be allowed for discussions to develop to the point that questions are effective.

• Logical thinking. A thoughtful process is used for finding solutions to problems, which often means asking a series of questions and following through on details that are unexplained.

• Self-control. You must be able to exercise self-control even when others are losing theirs.

• Caution. Finally, caution in this sense is the ability to assess, understand, and respond to the risks of the circumstances.

25 Are You Prepared to Ask?

Whereas some managers prepare for meetings or interactions, many do not. Preparation, although not a requirement for good management, is advisable in most circumstances. Managers attend meetings, read reports, listen to messages, and, for the most part, react. They neither prepare questions nor do they prepare for questioning. Some of them will surely succeed because of their experience and skill.

Higher-level managers can usually use this strategy if they have a strong supporting cast of mid-level talent, so preparation might not always be required of all managers in every setting.

I have seen only two successful approaches to lack of preparation by a senior manager. One approach is followed by a leader of a health-care agency who enters each meeting he attends clearly uninformed about the details of the discussion. He allows the attendees to speak and will ask them to continue discussing the issue at hand until he formulates his questions and takes the lead. His years of experience in this agency provide him with the kinds of precedents he needs to be able to recognize patterns of problems and similarities in issues. He then uses this history to guide his organization through problem solving. This behavior is well known to all members of his staff. However, he keeps them from taking his lack of preparation for granted by occasionally preparing for a meeting at random. Because his staff members are never certain when this will happen, they can ill afford to neglect to prepare themselves with the required data. He is intolerant of poor preparation by others!

A second approach, from an educator, is more a question of the appearance rather than a true lack of preparation. This manager moves from subject to subject with ease, carrying only a small notebook that is never opened. She asks thoughtful questions and is often underestimated in that she does not refer to notes. However, she reads copious quantities of information each evening.

These approaches are not recommended for most managers. Both of these people are experienced managers who are prepared by years of experience on the one hand, and have an incredible appetite for information on the other. So even here, when there may appear to be a lack of preparation for a specific subject, the managers are prepared.

There are, however, certain occasions when reacting is literally all that can be done. These may include surprise employee complaints, unanticipated hostilities in negotiations, sudden changes in leadership, and any type of confrontation that pits a manager against a unique problem or situation. The character I mentioned at the opening of this book, Dr. Doom, was well practiced at informing his management of bad news at the last possible moment, in decision-making meetings. But in most instances, preparation can improve the quality of any interaction.

Here are some recommendations for managers to prepare for asking questions:

• What is the purpose of the paper, meeting, presentation, report, voicemail, e-mail, or communication?

• Why you are participating, reading, or listening—what is your role?

• Questions to prepare:

Why are you specifically involved?

How do others perceive your role?

What results do we expect?

What are the significant issues, as I know them?

What do I hope to learn as a result?

• Are the important questions written down?

• What will you do when you get the answer (particularly what you might do with unanticipated answers)?

It is advisable you avoid reading any question if you are operating from notes. It is acceptable to refer to a list; doing so impresses people because they think preparation was done in advance. However, reading the question shows that you might be overly concerned with semantics—that you’re more concerned with getting the right words than you are with getting the right question.

26 What’s the Purpose of Your Question?

Asking questions, as simple an act as it may seem, can constitute a surprisingly subtle and effective management strategy.

—John Baldoni15

John Baldoni, in a monograph he developed for use at Harvard, outlines a number of reasons managers may ask questions. The list of possible reasons for asking a question is limited only by the number of questions that can be asked—meaning there is no limit. It is also more complex than just considering what you, the questioner, might have in mind. The listeners and respondents may read unintended inferences, implications, and management strategies into your questions.

“Why did you ask?” is the bottom line. It could be as complicated as “gut instinct” if you are probing for some hidden problem, or it could be a simple question about exchange rates. All specific questions are asked in the context of some general condition, situation, or event.

The general context of a question can fall into any of these business categories: planning, marketing, manufacturing, sales, service, technical support, human resources, finance, research, development, information, or other business-specific designator such as waste removal.

The business condition at the time of the question is a part of the general context, as is your position in the organization. We cover some additional issues about the role of a manager later.

A second element of the purpose is what it is you intended by the question. When you ask a question, you are addressing seven basic elements of purpose. Your brain covers these issues at nearly the speed of light:

- Data. What do I need to know?

- Specificity. Am I specific enough?

- Time. Why do I need to know this now?

- People. Is this the right person (people) to ask?

- Implication and inferences. What are the possible ramifications of the question?

- Response. What do I do in response to the answer?

- Manner. How am I going to ask?

The mental process that answers these questions to satisfy your needs is fast, efficient, and often unconscious. Few people raise issues without having mentally gone through a similar list. One element is often ignored, and only after a question is blurted out does the manager think twice: inference.

Asking a question communicates a lot of information. Psychological analysis is not our intended purpose here. However, I have seen managers attempt to reel in questions that have gotten away from them. The manager might have wanted to infer something without stating it, and that’s all right. Inference by accident is what you need to avoid.

Baldoni cites a number of general reasons for asking questions, such as “getting the lay of the land,” planning, diagnosing problems, or making a change in mission. However, he raises two additional reasons that are worth mentioning: using questions to challenge the status quo, and using questions to encourage dissent.

Questions along these lines often go unasked. Decisions are often unchallenged, and elephants enter the room unnoticed. Consider asking questions to encourage dissent, or as a challenge when things are “going well” or when things are “going poorly”—two conditions when critical thinking can add great value.

You must ask them with an awareness of what is being inferred by asking. A manager who asks a plan or strategy be challenged must communicate, as part of the question, the purpose of the challenge. Otherwise, the manager runs the risk of actually undermining the implementation of that strategy.

The basic message is that a manager must always be aware of the purpose of asking. All questions from management, unless experience dictates otherwise, will be treated as if they have a distinct purpose, whether you have one or not.

27 Words: Are Some Words More Important Than Others?

The most critical need for attention to wording is to make sure that the particular issue which the questioner has in mind is the particular issue on which the respondent gives his answers.

—Stanley L. Payne

Stanley Payne was one of the founders of market research as we know it today. Wording, as Stanley Payne suggests, is important. You might think of this as one of those duh! statements. But, how many times have you heard a question asked, and then the questioner says, “Let me explain what I mean”? Why? Why should anyone have to listen to a question and then listen for the interpretation? Some managers make a habit of this.

They might use this “chance to explain” as a rhetorical device, a type of stall so that they can collect their thoughts while maintaining control of the discussion, or they might just be unprepared. The fact is that questions should be made clear enough when they are asked that interpretation is unnecessary. Word choice and use is helpful to consider in advance of interactions.

Some words, readily available for use, can go a long way toward helping managers improve their questions, and thus reduce the need for interpretation. Payne identifies in his market research work a number of good words to use in questions—words that can help lead to improved questioning and improved answers. For example, words and expressions such as the following:

Could...

Would...

Should...

Under what conditions...

And...

These words/expressions introduce an open question. They imply an interest in the information that is to be conveyed rather than in obtaining specific answers. They are good words to use early in any discussion process.

Other authors call for the use of “high-impact words.”16 These types of words provide an opportunity to give greater emphasis to a particular question than other words. Attorneys, for example, make use of impact words to help them establish meaning or to imply some intent as they build their arguments. Managers can also use them for effect rather than for building a case or impression before an audience. A few of these kinds of words appear in the following examples.

Q: What exactly is woffle dust?

Q: Is it a guess that our patent will be granted?

Q: Are you certain this material was from the same batch?

Implied standards, criteria, and performance measures can be suggested or communicated through a completely different set of words. It is important to consider the use for these kinds of words to give importance to the questions you ask.

Q: Are you properly monitoring the capital accounts?

Versus: Are you monitoring the capital accounts?

Q: Is this work consistent with standard industry practices?

Versus: Are you following standard industry practices?

Q: Are you making the appropriate changes?

Versus: Have you made the changes?

Q: Who supervised, and at what time was it completed?

Versus: Who supervised, and when was it completed?

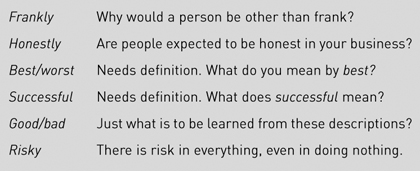

If there are “smart” words, then you can be sure there are “dumb” ones, too. An article that appeared in the Phoenix Business Journal mentions “dumb words” used by salespeople. The words they cite are commonly used all over the business community, words such as frankly and honestly, which imply that the speaker might not be frank and honest all the time.

Open questions allow for a lot of latitude, but even then, words that need definition should be avoided. How does anyone know what the “best strategy” is? You know only choices, and even these choices face changing market conditions. There are no constants in business. Qualitative words offer an opportunity for respondents to equivocate.

Manager: I thought you forecast successful distribution. How can you call it successful when all but one of our Ming Dynasty vases arrived broken?

Distribution manager: Yes, it’s true that only one arrived unbroken, but the vase was received on time by our most important customer.

Manager: What exactly do you mean by most important?

Distribution manager: The customer is the CEO’s mother-in-law.

The words are important. Any time a manager uses undefined terms, or allows the use of nonspecific words in a response, it creates an opportunity for unmet expectations later.

An example of what not to do was found in a corporate training video for a well-known service business in which integrity is fundamental to the business. The trainer on the video actually promoted the use of these expressions for its customer service people: “Trust me...,” “I have your best interests...,” and “This is the truth....” These expressions are poison. Unsolicited responses from people viewing this training video for the first time generated cynical comments from a small group of potential customers.

Try to avoid asking people to be frank with you or to express their honest opinion. This clearly communicates that you suspect that the opinions they have rendered in the past may have been dishonest.

All business inquiries should be earnest, using simple, straightforward language.

Simple words, used with emphasis or used in combination with other easily understood words, work best.

28 What Are the “Right” Questions?

What are my weaknesses? How can I balance them?

—Rudolph W. Giuliani17

If there were ever a list of the “right” questions for managers at all levels to ask of themselves, these would be at the top. These are questions that managers should continually ask. The answers can act as a guide for the manager on what to ask, of whom, and when.

I have already offered up a number of “wrong” questions. But, is the converse true? Are there “right” questions? The simple answer is, yes; technically, anything that is not wrong is right, but there is another way to think about this.

The right question is the one that yields the right answer, including its potential impact on others. We have already seen how asking a person to tell a lie can be a disaster, even if it doesn’t have a negative impact on the person to whom it is addressed.

Right questions elicit right answers for a specific business purpose at the appropriate time and place in a manner that fosters the necessary rapport. A number of good resources are available that describe how to find and ask the right questions.18

Most of the time, the right question is a product of critical thinking, as suggested by M. Neil Browne and Stuart M. Keeley in their book Asking the Right Questions: A guide to critical thinking.19 However, “right” questioning is a situational skill. It is often the product of a collective thought process—the results of a series of interactions in a single place or over an extended period of time.

Understanding the situation is the key to understanding the right question or questions. There are always a number of right choices available, too—which might have a number of possible outcomes. It all depends on what you need to accomplish.

These guidelines may help in determining whether the right question has occurred to you or whether you might want to think more critically about the situation confronting the business:

- The question is meaningful.

It can be linked directly to a critical issue, strategy, or objective for the business.

Q: How were we able to achieve a profitable year when, in fact, we were losing money at the beginning of December?

- It has impact.

Both the question and the answer have a potential impact, a benefit to the business.

Q: With our line down, what do you think about contract manufacturing our product with our competitor down the street?

- You have made it clear why you are asking.

Q: I am asking to gain an understanding of how these things happen so that we can avoid repeating them in the future, not to engage in a witch hunt. So tell me, what went wrong and how do you think we can avoid this from happening again?

- The question matches the reality.

It is consistent with the reality of the situation. It is not out of character for the manager, the sense of urgency is appropriate, and it does not create skepticism in the person to whom it is directed.

Q: Mary, we have known each other for years, and I have come to rely on your judgment in these situations. Is there any way we can save the deal?

- Know what to do with the response.

This applies to all questions under all circumstances.

So why not trust your skills, your gut, or your experience? Why not just ask the questions that your gut instincts tell you are the right ones, or the best ones, or the questions you have seen work in similar situations before?

The danger is that our instincts may be wrong. Our instincts, by and large, are based upon our past experiences.

—Paul Schoemaker20

All business decisions will affect the future, and as every prospectus says about new opportunities, past performance is not a guarantee of future success. Actually, past success could conceivably cause future failures by blinding a company from asking or answering important questions.

29 Is Everything We Ask Important?

We would all like to think so. Reality is different. The way a question is treated, by our tone, facial expressions, body language, and gestures gives it importance. Yet, few questions are critical. The category a question falls into gives it importance as well as a perceived sense of urgency.

Three general categories of interest generate a business manager’s questions:

• Things that affect the business in the short term

• Things that affect the business in the long term

• News

The first category of questions is the one most people respond well to. The second, although important, lacks urgency unless a manager gives it a sense of importance. Anything that does not clearly fall into the first two categories is a news item.

Managers who focus on the news elevate it to a status of importance that it might not deserve. It is a category of interest, and questions about the news should be treated as if they are just that—news. News is nice-to-know stuff, about entertainment, weather, or sports.

Q: Have you heard about the new robotic prostate surgery? Do you think it will affect demographics in the long run?

Q: What do you think about those floods in China? (when your business has no business in China)

Q: Did you know the boss is a Yankees fan?

Continued questioning with a sense of urgency concerning items of interest that lack ties to important business issues may have two effects. First, a manager who does this all the time is sending signals of an adult attention-deficit problem. Second, it might communicate that everything is important, ultimately having a negative impact when it comes time to focus on key concerns. Better to save the sense of urgency for those issues that require a high level of attention.

When asking questions, particularly of employees, consider which category the question represents, and then match the sense of urgency to the question.

30 The Manner of Asking a Question: Style

There is matter in manner.

—Francis Wellman21

There is a single unanimous recommendation from all sources on questioning: If you are asking in person, speak clearly. Include voicemail in this recommendation. too. Although you might not be physically present, your electronic residue is, and it represents you.

I’ve assembled a consensus list of recommendations here for consideration, borrowing heavily from texts designed for attorneys. Courtroom lawyers need to have the sharpest questioning skills; otherwise, their clients will suffer. Managers also need sharp skills; otherwise, their business will suffer.

These are basic and commonsense recommendations. Yet, due to habits or lack of attention, they are not always practiced. Consider, for example, this case of the CEO of a new business.

Whenever she was about to ask a member of her staff a question, any question, she folded her arms—literally, every single time. Her staff automatically braced themselves. She asked good questions, and they were highly skilled. However, the arm-folding habit always made them edgy and defensive. It took almost a year to break her of this habit.

The manner of the question, the way in which it is asked, and the actual communication of the question are all just as important as the substance of the question.

31 What Was That You Said?

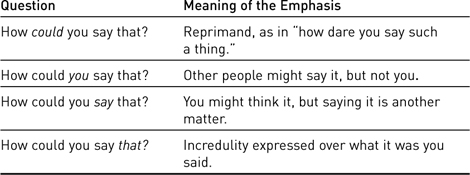

According to Stanly Payne, whose wise council guided market researchers for many years, a question changes depending on where the emphasis is placed.

The same question can have different meanings depending on where the emphasis is placed. I mention that point here so that you are consciously aware of it, and so that as you consider the phrasing of your next question, you can think about adding meaning by using emphasis rather than words.

I chose the “how could you say that?” example in this section deliberately. It was one of the standard habit questions of a manager I once worked with. He always asked the shortest possible questions and packed in as much meaning as possible. It was his way of challenging people even though he was a nonconfrontational manager. The technique worked most of the time.

Consider where the emphasis is placed when you ask a question. Can you add more meaning by using emphasis?

32 Can You Use a Raised Voice?

There are many right ways of asking a question. A military drill instructor may yell questions in the face of a raw recruit.

Drill instructor: Mister, what happened to your shoes? DID YOU SHINE THOSE SHOES WITH A BRICK?

Raw recruit: (responds by sweating profusely, while holding back a smirk because, after all, shining your shoes with a brick is a funny concept.)

Drill instructor: What are you laughing at, Mister?

A business manager should not yell in the face of a new employee—no matter how dull his or her shoes are. That said, sometimes a raised voice might be required. Some people recommend against raising a voice under any circumstances. I am not one of those people.

I believe it is permissible to raise your voice as long as you follow these simple rules.

- Use a raised voice so infrequently that people will comment, “Wow. I never heard a raised voice before.”

- Avoid using the raised voice with groups, because it creates an “us versus them (you)” mentality (unless that is your objective).

- The incident must be of sufficient gravity. Others who are within earshot must perceive you to be entitled to raise your voice.

- Ask the question by speaking (yelling) directly at the person, looking him or her in the eye.

- Do not hold back. If you are going to do it, do it like you mean it.

- Try to use rhetorical questions. You are not really looking for answers when you yell, are you?

- Avoid yelling contests. Deposit your rhetorical question and leave, without slamming the door.

- Do not yell questions out of anger. Yell them out of purpose.

- Maintain your self-control. Do not overdo it. Get it over with quickly.

- Remove yourself quickly and allow the object of your ire to decompress.

Can I give you an example of when this manner of questioning might be used? Yes. What do you do, for example, when a person violates a direct mandate of the company, not once but three times? I can recall yelling only one time at the office, and it was because of this situation.

One of the more senior managers in my organization had thought better of a company decision even after we had a full discussion with our legal department. The decision was to end a business relationship with another company and to do it quickly and directly.

This smaller company had approached us to produce materials for a new type of construction product they intended to manufacture for outdoor use. Although we had technology that did work, and our research laboratories were able to turn out material that promised to be potentially useful, the business did not look economically attractive to us. The decision not to produce the material was made just as it was for many others.

A month later, I discovered the decision had yet to be implemented. This was not the raised-voice time. That happened six months later, after discovering it had still not happened. It wasn’t a moment that I felt good about. Although I had been lied to repeatedly, I felt it was a failure of my management that it had occurred. I had assumed, improperly, that the matter had been resolved.

My questions went something like this.

Me: Steve, I never did hear the final response on your interaction with Universal Outdoor Flooring. What happened?

Steve: You haven’t heard because I haven’t told them.

Me: YOU WHAT?

Me: Are you going to call them now while I wait here in your office? Or do you want to come by my office in ten minutes and report on the call? OR DO YOU WANT TO BE FIRED? RIGHT NOW?

I gave him three alternatives and then walked out of his office, leaving him with alternative number two to do or number three to consider. Steve popped in my door ten minutes later—job done. I asked him to put a letter to legal, copying me, and send it with a return receipt to the other party. I no longer trusted him, and I told him so.

My judgment not to follow up after the first delay was poor, although I had a hard time believing than an experienced upper-level manager with more years in the business than I had would have done this. The underlying condition that caused the raised-voice incident was making assumptions and then not asking questions.

Although I support the possible use of a raised voice, according to the rules stated previously, it also behooves a manager to do whatever is possible to anticipate a situation such as this and prevent it from arising in the first place.

33 What Is Your Personal Style for Asking Questions?

Most managers have a general style when questioning people. It is their default mode. It’s a habit. If a manager consistently uses one style, people start to rely on it. This is positive because it presents a consistent face for people to react to. Consistency is valuable in normal business settings. A consistent style, however, may be just as much of a problem for a manager as habit questioning.

It might preclude the ability of the manager to gain new perspectives or react to new circumstances. For example, if a manager always takes a neutral stance, others may be influenced to do the same. This is neither good nor bad—but people have a great tendency to emulate the successful managers that are promoted through the corporate system. Imagine a whole business full of neutral managers. How would they get anything done?

I used to watch a group of managers play a game called “Monkey.” No one offered an opinion or would accept responsibility for any problem that was not directly under his or her control. The problem, or answer to a question asked by the boss that was about a business problem, became the monkey. They would shuffle the monkey around the table so that it would land on anyone’s back but their own. One member of the group would actually dance this virtual monkey around the table as if it were a marionette, prompting chuckles among the group—uproarious laughter if it actually landed on someone. Most often, the “monkey” was left forlornly alone, waiting, festering into a great ape of a problem.

This stalwart team was led by a manager whose style was 100 percent neutral. He was never flustered, nor did he ever appear to be swayed one way or another by any argument, no matter how persuasive it might be. He maintained neutrality because he was overly concerned about what the business leaders above his level thought. His management team adopted this style. “Monkey” was their game.

Problems started to pile up over the course of his two-year tenure. Lower-level managers and staff were constantly paraded in before the management team to present solutions, proposals, and projects for consideration. Everyone believed this guy was destined to become a corporate officer, and his style was being adopted by many people (to the detriment of revenue and earnings). The “Monkey” game ran full time until he received an offer from a competitor and left the company. I can only assume that he continued to be the Switzerland of managers.

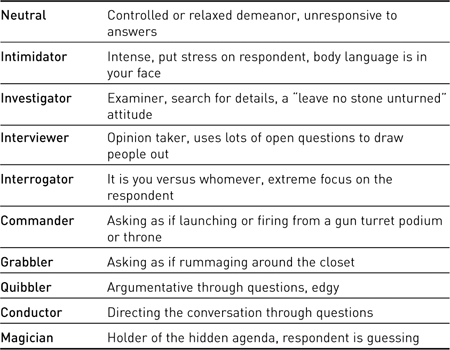

Neutrality is, of course, only one style of asking questions and practicing management. The list in the following table is a general description of questioning styles as opposed to management styles. Some may be practiced as one in the same. The neutral questioner may indeed be the neutral manager just as much as the intimidator may be a style that works both ways, too. The objective is for each manager to know the style that is most comfortable for him or her and to then consider, when the circumstances are correct, adopting another approach by adopting an alternative style or styles.

Table . Questioning Styles

Your style of asking is a combination of qualities represented by the labels in the preceding table. Rapport must be established with the respondent if you want the best answers. Each of these types of styles will generate different relationships. Even the intimidator develops a rapport with people. It just takes longer to get it established. One style has a distinctly negative influence and should be practiced with care: the magician.

Hidden agendas kill trust. If questions communicate a hidden purpose, or appear disingenuous in any way, the trust that is a complicit part of asking questions for managers will disappear. Magician questioners pull the proverbial rabbit question out of the hat to surprise their “witness.” Use this with great caution, and if you find it necessary to employ, use it so sparingly that it is truly a surprise. A chief technology officer used to buy a different set of laboratory technicians coffee every morning. He used this opportunity to gather intelligence that he would use at key moments to ask challenging questions of his staff about yesterday’s experiment that went awry. No one appreciated his magic act.

Answers will become guarded, and all of your skills as a questioner will be reduced in their effectiveness. If used consistently over time, you will be left with your rank and title as the only means to elicit answers.

To maintain their effectiveness, all styles should be based on these four basic qualities:

- Be genuinely curious.

- Practice your style actively by maintaining interest throughout the interaction.

- Use patience—even a patient interrogator can get a lot of mileage out of her questions.

- Project integrity.

34 Who Is Asking the Question?

What is your role in the organization? What are your responsibilities? The answers to these questions may give your question more or less weight than you intended.

Any question raised by a high-level manager in a business is quite naturally given a great deal of weight. The organizational rationale goes something like this: The manager must think this is important, because the question was asked. This kind of rationale often wastes money, wastes time, and raises more questions than it answers. Consider this example. The discussion takes place between a marketing manager (MM) and her subordinate, an experienced product manager (PM).

A vice president had torn an ad out of a magazine and sent it to the marketing manager with a question written in the corner.

MM: Have you seen this note from the VP?

PM: Yes. He wants to know if we are aware that there is a vacuum cleaner with the same name as our new product.

MM: What are you going to do about it?

PM: I wrote my answer right next to his question. See it up there in the corner of the paper?

MM: Are you crazy? One word?

PM: Look at his question. He wrote next to a picture of a vacuum cleaner that has the same name as our product: “Is this a problem?” My answer was “no.”

MM: You cannot give a one-word answer—just saying no. He needs more than that.

PM: Why? He tore a page out of one of those in-flight magazines and wrote in the corner.

MM: That doesn’t matter.

PM: You’re right. It doesn’t matter. That’s why he gets a short response.

MM: We need to give him a comprehensive reply.

PM: Look, no one is going to confuse a tractor with a vacuum cleaner.

MM: But we have to make certain this isn’t a problem. Have you?

PM: Yes. We have checked with everyone, received a legal opinion from our attorneys, and even called the vacuum cleaner folks to be certain. There is no problem.

MM: We need to explain this to him.

PM: I’m much too busy. It’s not a problem. Don’t make it one.

MM: Well, this isn’t good enough. I’m going to check with legal and get a review of this right away.

Reassurance was what the VP was looking for. He said so, three weeks, thousands of dollars in additional studies, and many wasted man-years of meetings later. The marketing manager was reacting to the position rather than to the question. Was this an overreaction? Yes.

The simplest response would have been the best route to determining whether this was indeed what the VP was looking for. If more than a simple response was expected, he would have communicated differently.

The question and the rank of the person asking are always intertwined. They simply cannot be separated. So, ask questions that are important, and ask them in a way that communicates the kind of answer you expect.

In this case, a simple question on a torn-out page of a magazine should have been a clear signal that the VP was “just checking.” He had confidence in his organization—that is how he made it to VP. No one gets to that level by himself or herself.

In this case, the one-word answer was all that the VP wanted, and is what he received from the product manager. What he learned from the marketing manager was that she might not be the right person for the position she was in.

Rank has its privileges, not questions. If they are clearly communicated, the answer should be expected to mirror the question.

35 Who Are You as a Manager?

Roles are not just a function of title. They may also be a function of the esteem accorded to you, your length of service, your special skills, or a host of other reasons. To get back to a point made earlier, there are no such things as casual questions in a business. They can be asked in a casual manner, but questions are perceived as a function of many aspects of the situation—the role of the manager being the key.

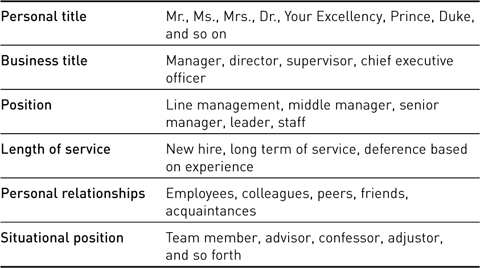

There is a hierarchy of roles ascribed to people that act as lenses through which their questions are focused on any respondent. Consider how you think about others you interact with, and then look in the following table at this list of roles played by people you interact with in a normal business setting. Any individual may hold a number of these positions.

Table . Multiple Formal Roles of Questioners

It is important to remember that one of the most important aspects of the manager’s job is to avoid taking things for granted. Many new managers can get off on the wrong footing with an organization by asking questions the wrong way because they might be unaware of their own “role set”—that set of roles attributed to them by others. The following approach to asking questions is not to be emulated. This was the approach taken by a newly assigned manager one month into her new assignment.

How do you do things around here?

Why do you do it that way?

Have you considered any other options?

On the surface, this appears to be a natural and innocent approach. The new manager was on an information-gathering mission. She was striving to learn all she could about the business she was now responsible for. The organization detected her separateness in the use of the word you whenever she asked a question.

She was treated with some deference because she held a doctorate degree and her business title was manager. However, she misinterpreted the deference paid to her as acceptance into her positional role of middle manager, her personal relationship roles with her direct reports, and the situational role she found herself in (trying to grow the business).

She persisted in using you when asking questions for the next few months. As a result, her team distanced itself from her. They offered only answers to her questions, and all without insight or explanation. The employees cut her no slack. They expected her to be a part of the team—as one of their leaders, and ask questions showing she was accepting the responsibility. It didn’t happen. Her tenure was less than a year. What could she have done differently?

How does this work?

What do I need to know about this now that I’m here?

Who else might be able to help us?

How has this problem been resolved before?

Who has the most experience tackling this problem?

These questions have the same intent. It is equally important to avoid the use of the word we—at least at the beginning of a manager’s tenure. In the case just described, things might have gone just as poorly had she asked, “How do we do this or that?” The use of we might be interpreted as sarcastic, or lack the genuineness of we from a longer-term manager. She failed in her new assignment, too. She thought her transfer was a reward, when, in fact, the upper managers were trying to determine whether this person was a senior management candidate. She didn’t make the grade.

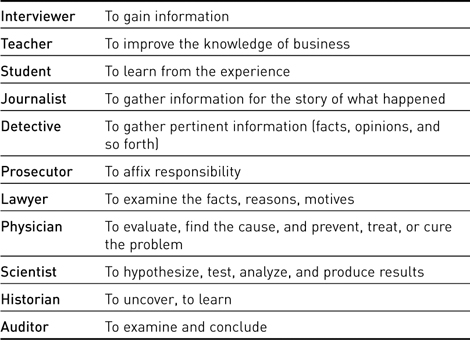

During the questioning process, a person takes on another role. Depending on the situation, once again, that role is somewhat different from the formal position one may be paid for. Probing, for example, usually shifts a manager into a different role automatically.

Informal questioning roles and their business functions are noted in the following table. Managers can move among these roles depending on what is called for in the situation confronting them. Assuming any one of these roles for just a moment can help establish new lines of questioning and important new perspectives.

Table . Informal Situational Role of Questioner

Two cautionary notes need to be sounded while we are discussing roles. First, the question should fit the person you are asking. Asking questions of someone who is incapable or not responsible for providing an answer is destructive. If you are looking for the cause of a problem and need details, for example, asking the hands-on employees, the knowledge workers, is appropriate. Asking for insight into strategic direction should be reserved for those people who have strategy development as part of their responsibilities.