Chapter 6. KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid)

Surfers wait for waves during the 2006 Rip Curl Pipeline Masters competition at the Banzai Pipeline on Oahu, Hawaii.

The photograph on the following page of a fencer winning the Olympic gold is one of the images that came as a result of everything I’d learned and practiced up to that moment. It is those lessons, both good and bad, that allow me to make bets and take a calculated risk.

I was photographing the Olympic women’s gymnastics semifinals in Beijing in 1998, while one building away, the men’s fencing finals were occurring. At a certain point, I knew I needed images from both events.

Julien Pillet reacts to winning the gold medal in the Men’s Team Sabre final in the 2008 Summer Olympic Games.

ISO 1250 f/2.8 1/1000 200mm

I started with gymnastics because the preliminaries for fencing were irrelevant. However, photographers had been waiting at the fencing venue for five, six, or seven hours to secure their seat, to ensure that they would get the gold medal shot. And while they would shoot many images while they were waiting, it was obviously the gold medal moment that was the most important.

Since it was the semifinals for gymnastics and there would be no gold medals that day, I shot for about two hours, and I then took a risk and left early.

The other photographers were wondering where I was going.

“Don’t worry about it,” I said, and began to make my way through three security checkpoints just to reach the building across the street.

When I finally got up to the fencing venue, the fencers were in the middle of a match. I looked over to the fencing coach, who happened to be French, and I asked him in French, “What’s happening?”

“It’s the gold medal match,” he said.

“Who’s winning?”

“We are,” he said. “Match point.”

I literally showed up at the last fencing point—the match point, during a break in the action when people were allowed to get up and move. I still had my rolling bag in my left hand, and I had my camera in my right. I got down on one knee, raised my camera with a 70–200mm lens to my eye, focused, and got this picture. Could you ask for better?

All the photographers looked back at me with sheer disgust that I had shown up at the perfect angle, at the perfect time, and nailed the image while they had been waiting there for hours.

When you do the Olympics, you realize that even though an event lasts five hours, the really important things happen at the end. You definitely can’t plan on showing up 30 seconds before the final and always expect to get the shot. But the important lesson was that by knowing my equipment and being prepared, I was able to get the shot when it mattered most.

Starting Simply

The best gift I received from my dad was one camera and one lens. He gave me a Nikon F3 with a 50mm lens and what was called a brick of Kodak Tri-X, which consisted of 20 rolls of film. That was the only lens I had, and when you only have one lens, you learn how to use it inside and out. You learn where it’s weak and where it can be really strong.

At 15 years old, I didn’t have the extra cash to spend on the luxury of photography. My mother was divorced, and my father was living in France and not making a boatload of money. So I went to shoot Bar Mitzvahs and weddings with the hope of making a few hundred bucks to buy the next lens. It took me a year or two to have a collection of lenses.

With each lens purchase, I would have the time to work exclusively with that lens for months. When I got the 24mm lens, I learned its sweet spot; and I learned that if I moved too far, it wasn’t an effective lens choice, and if I was too close, the images suffered from too much distortion.

I began to learn that each lens, each choice of equipment, had to be rooted in what I was trying to achieve with the camera. Otherwise, I would be bringing everything and the kitchen sink with no guarantee that I would get the shot.

As much as I evangelize gear for the companies with whom I work, it’s important to remember that gear alone never makes the picture. Gear that doesn’t work or that you don’t know well stands in your way of getting the photograph.

Sometimes you definitely need a specific piece of gear, because it’s the only piece of gear that will allow you to make that picture, but people think that that’s true a bit too often. The reality is that you can make a great photograph with virtually any lens or camera there is, but only if you know what you are doing.

Really, it’s only their knowledge and experience with those lenses that will make the difference between getting the shot and not getting it.

New Orleans: one year after Hurricane Katrina (2006).

ISO 100 f/22 20.0s 57mm

Thousands of Afghans fled to Pakistan fearing for their lives, either from Taliban reprisals or bombs falling from above (September 9, 2001).

I moved in close with a 24mm lens and chose to fill the frame to eliminate all the potential distractions.

When the Situation Dictates the Choice

I was in a Pakistan refugee camp not long after 9/11, photographing under horrific noon light with an early-generation digital camera that did not capture Raw files. Many potential subjects were suffering from “chipmunk lighting,” which is what I call it when you have horrible shadows under people’s brow, nose, and chin. So the light was terrible and the camera had some challenging limitations.

Because of the high-noon light, my choices were either to shoot in open shade or to expose the shot to the sky and create a silhouette. I chose the former because this was going to be a very straightforward photograph. This is a mother who has left Afghanistan because she feared getting bombed by American B-52s. The Taliban shot her husband in the head in front of her and her daughter as they crossed the border.

She was talking to a reporter about her fear and showing him her passport, while I framed her and waited for her to take a pause. I then shot this frame.

The choice of the best lens for this situation was a simple one. We were in a very confined space. There were other reporters and TV crews around us. So I moved in close with a 24mm lens and chose to fill the frame to eliminate all of the potential distractions. Instead, the viewer focuses on the woman’s eyes and those of her daughter looking over her shoulder.

Don’t Be Overwhelmed by Gear

Master photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson and David Alan Harvey walked around with a Leica and a 35mm lens, and maybe a second body with a longer or wider lens. That’s it. And that’s because they knew their style. They knew what they were looking for. They saw shots every second that could be shot with a 400mm f/2.8, but that’s not what they were going for. They’ve made a conscious decision to let those shots go because of the style that they were pursuing.

Just because you can afford to buy a lens or have it available in your bag, it doesn’t mean you should use it or even carry it around. When you take too much gear or, more important, when you overthink things, you can become your own worst enemy.

Sometimes the very best thing to do is just to bring one camera and one lens. It is then that you are completely free to move around, blend in, and not be distracted by having to put this big camera bag down every time you’re ready to make a picture.

The philosophy I try to live by is KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid), because while I’m busy thinking about the gear, the moment has come and gone.

And although missing a shot can be disappointing, it’s always important to remember that this isn’t rocket science. If you miss a photograph, no one dies on the operating table. No, one falls from the sky because you designed a rocket poorly. This is photography and it should be fun; at it’s best, it’s liberating.

Simple Image, Simple Choice

The photograph on the facing page is from a series on how man interacts with nature, and I think this image is one of those beautiful, quiet moments. I was at the beach with my family. One of the most important rules of photography is always to have a camera with you. The photographer Chase Jarvis said, “The best camera is the one that you have with you.” I think that’s a great quote, and it’s very true. In this case, it’s a very simple image.

I was walking with a Leica M8 and a 35mm lens. I saw this man wearing a white hat and a white T-shirt walk into this body of water, and it became a very graphic moment. There’s a lot of negative space with that one spot of light.

It’s one of the few times I shot in aperture priority mode. In this case I turned the EV (exposure composition) down one-third to get a nice, rich negative (although in this case, I was shooting digital), and from there it was just point and shoot to capture the moment. There’s no need to overcomplicate things. Sometimes the simple approach wins out, and I think this was one of those times.

Lens: “Little Black Box,” Sag Harbor, New York, 2007.

ISO 320 1/500 26mm

Core Equipment

My core equipment would be one or two bodies that have full-frame sensors. If I had just two lenses to go to heaven with, they would likely be prime lenses. They would be a fixed 35mm and a 135mm. And if I could manage it, I would also include a 500mm f/4, because I really love super telephotos, which is what I use to take a lot of my aerial and sports images.

But for the average person I would recommend a 24–70mm f/2.8, because it covers a wide spectrum of focal length. And the second lens would be the 70–200mm f/2.8. Between those two lenses, you have enough range to cover practically anything in the world, be it fashion, nature, sports, or photojournalism. Those are the two mainstay lenses.

After starting with two bodies, each with one of those lenses, I would probably go to 16–35mm f/2.8 for a wider focal-length range and more dynamic imagery.

Weight and size are a huge factor, so the Canon 5D MK II series is probably my favorite body ever. It’s the perfect size. It’s close to weightless, rugged enough, and its battery lasts quite a long time.

The Canon 1D series bodies are the ones you take to the big assignments like the Olympics, a war, or any extreme shooting situation where you know that a quick trip to the repair shop is not going to be an option. The Canon bodies give you reliable performance that’s insured by weather sealing and resistance to extreme heat or cold. They are the Rolls Royces of camera bodies but I think most people don’t need them.

If I had just two lenses to go to heaven with, they would likely be prime lenses. They would be a fixed 35mm and a 135mm.

Bonneville salt flats in Bonneville, Utah (2005).

ISO 100 f/8 1/500 35mm

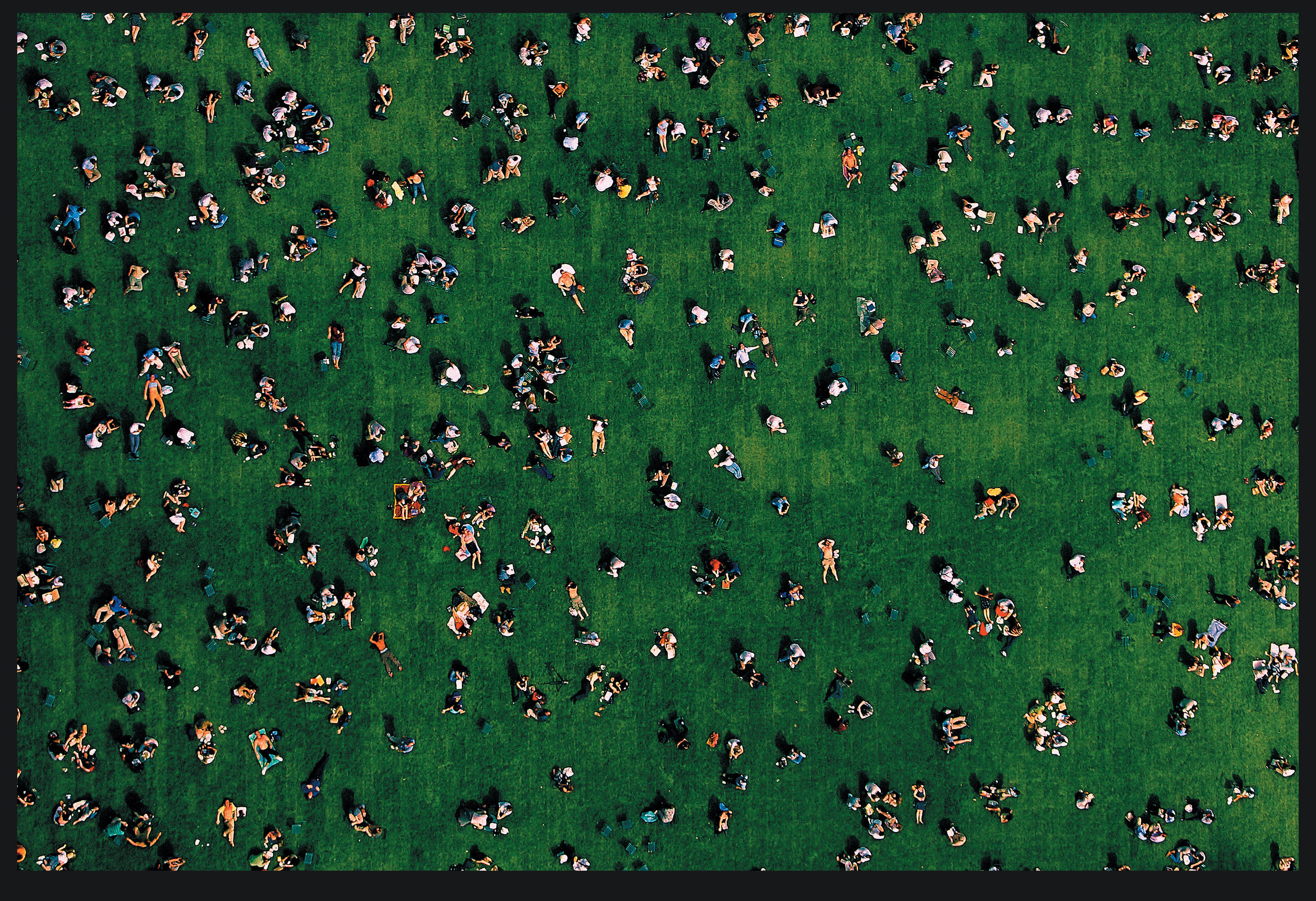

Hundreds spending their lunch hour in Bryant Park in April 2002, one of the first times New Yorkers had ventured out en masse to enjoy the sunny weather since 9/11.

The Right Lens for the Job

This image of Bryant Park is actually not an aerial shot taken from a helicopter. When you don’t have a helicopter in the budget, try to find a tall building.

This particular day was not a big news day and the newspaper didn’t have a big news photo, so they had to find something to put on the front page. The deadline for the front page was 4 p.m., and I was rushing out of the office with only two hours to find an image for the paper.

I drove away from the office to Bryant Park, where I saw this mass of people out in the field. From ground level, a wide-angle lens would have made it very hard to show the number of people there. So I called the building manager I knew for the Verizon building and asked if I could go up and gain access to one of the office windows on the 50th floor.

I got up there and made a series of images with a 28–300mm zoom lens. The lens offers a pretty incredible range, and it’s a very useful lens for news because you can shoot pretty much anything. When you’re running around for breaking news, you don’t have time to sort through three, four, or five cameras and ten lenses. You’ve got to move really, really fast.

I tend not to use that lens as much anymore because it’s a bit slower with regard to f-stop, and while the optical quality is quite good, it’s not as good as the 24–70mm or the 70–200mm. While I took this shot with a 28–300mm zoom lens, I had to make sure I had a fast enough shutter speed to freeze any sort of vibration, in this case 1/500th of a second or higher.

This was a really cool moment: It was the first spring after 9/11, and I think the photograph—which showed up three or four columns wide on the front page of the New York Times—really struck an emotional chord with New Yorkers because it was the first time they saw people going back to normal life.

I saw this photo cut out and hung in people’s cubicles four years later just because I think it struck that chord that a newspaper photo can sometimes do. It has always meant a lot to me for that reason.

Portrait of a surfer in Ventura, California, 2008.

ISO 100 f/6.3 1/15 45mm

Accessories and Workflow

I always have extra batteries, and I always make sure to charge them before I go to sleep. No exceptions. Ever. No matter how tired I am, no matter what the excuse is, I never go to bed without making sure my batteries are charging.

I tend to have a dozen memory cards with me. I always keep the cards on me, usually in a fanny pack, in my pocket, or clipped to my belt. You never want your memory card or batteries more than a hand’s reach away from you.

I also separate my memory cards into two wallets. I never have all my memory cards in one wallet. So, God forbid I should lose one pack, I have another set at the ready.

I place empty formatted cards face-up in my Think Tank Pixel Pocket Rocket card wallets. After I’ve used them, I flip them over so I see their backside. That way I never have to wonder whether a card has data on it or not. Once I’ve copied the files over, I put them face-up, but inserted vertically, so that in case the hard drive to which I’ve copied the files fails, I know I still have the files on the card.

Unless I’m doing time-lapse photography, I don’t use the biggest cards available. I don’t want to put too many eggs in one basket—you never want to fill your card fully; you always want to leave a little space, because that’s where you have the potential to run into problems with data corruption.

You don’t need many accessories beyond lenses, charged batteries, and memory cards. However, I recommend that everyone not walk around with their lens cap on their lens and instead keep them stored in your camera bag. The only time I ever use lens caps is when I’m protecting lenses from damage during shipping.

And without exception, the first thing, you should buy with every lens is a quality haze or UV filter such as a Schneider B+W or Tiffen. The purpose of such a filter has nothing to do with the haze or the UV; its purpose is to physically protect the lens. It’s a barrier that protects the front element should you drop it.

I find it ironic that people would buy and attach the cheapest filter to a $2,000 lens, or that they would spend $5,000 on a camera body and then buy the cheapest CompactFlash (CF) card. When you think about it, it doesn’t make much sense, considering the investment you’ve made and how much you are going to use that card or lens. If you are going to invest that much money on your camera or lens, don’t compromise on the cards or filters you use with them.

Last, I always have a chamois cloth, because it can provide a little added layer of protection when I wrap my camera in it. I can also use it to wipe away any dirt or gunk that gets on the lens or camera body.

Remember to Diversify

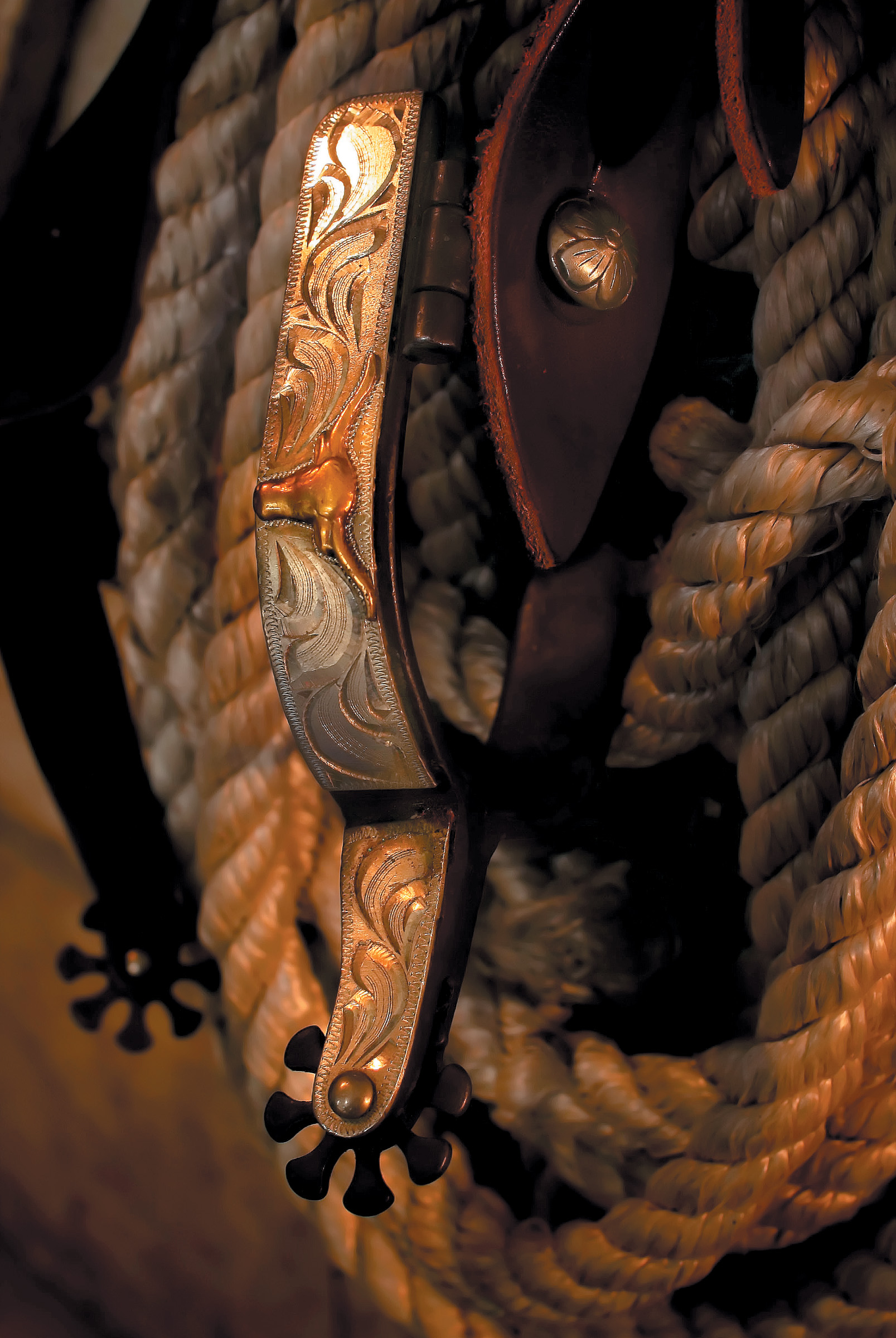

One very important thing to keep in mind when you’re doing a series of photographs is to diversify not only the lenses you use but also the type of photographs you take. This is an example of a macro shot—a detail shot of a spur inside a ranch for a commercial assignment on the paniolo in Hawaii. It was lit with two off-camera strobes and a macro lens. A macro shot gives the user kind of a break from the wide vistas or the super-long telephoto lens shots, and it’s a really important element to any series.

This image was made with the 24–70mm f/4.5 lens; one of the lesser-known features about this lens is that it’s an incredible macro lens. Not only is it a fantastic general-purpose lens with which you can shoot pretty much 90 percent of the stuff you’ll ever want to shoot, but also it shoots in macro, and that’s quite important.

One very important thing to keep in mind when you’re doing a series of photographs is to diversify not only the lenses you use but also the type of photographs you take.

A detail shot of one of the spurs in the paniolo stables in Waimea on the Big Island of Hawaii for an essay on the Hawaiian cowboy, or paniolo, in January, 2006.

ISO 100 f/4.5 1/3 24-70mm

Bringing It All Together

Pulling off this photograph of an engineer atop a gargoyle on the Chrysler Building took me seven months and 14 contractual rewrites with the Chrysler lawyers. And when it came down to actual shooting time, I had only one back-to-back sunset and sunrise in which to make the photograph happen. So, knowing my equipment was absolutely necessary. There were no second chances.

There were eight gargoyles to choose from, but this is the one I chose because it had the best point of view, where I could get both a sunrise and a sunset shot. I knew it was critical to get the camera lower, so I had to devise a way to see what the camera was seeing, because I couldn’t put my eye to the camera’s viewfinder.

The issue with this photograph is that when you stand on the 77th floor, level with the gargoyle, it intersects the city skyline, which is distracting. So I brought a Manfrotto Mega Boom, which provides up to a 10-foot extension arm with rotating pan-tilt head. I lowered it and controlled the camera using an Ethernet cable to my laptop computer. A wireless system wouldn’t work because the Empire State Building’s radio antenna was emitting more than 14 million watts of frequency, which created too much interference.

I was forced to compose by making small adjustments, frame by frame, as I viewed images on the screen of my laptop. There was no LiveView back then.

I chose to shoot this with my 24mm tilt-shift lens, but not for any reason other than it’s a very sharp lens.

As well as shooting at the right time of day, I realized that even though the silver on the gargoyle would pick some of the color of the sky, the engineer would have been rendered close to black. To solve this, I put two Profoto 7bs battery-operated strobes about ten stories down, pointing up with CTO orange gel to light the bottom of the gargoyle. I put one 7b behind him with the grid, also the CTO, to rim-light his back and arm that you can see.

Then, because I didn’t want to go out there, I had him put on two Canon Speedlights with orange gels set off by remote wireless triggers to provide illumination for his face.

So, there’s a lot of technical stuff going on in what is ostensibly a simple image.

An engineer kneels on a gargoyle on the Chrysler Building in New York City (2006).

ISO 160 f/5.6 1/250 24mm

It’s the Small Things

A shot such as the one of the Chrysler Building could have been ruined by virtually anything that went wrong, but the reality is it’s the small things that almost always get you.

If you study 95 percent of the failures to see what happened, you’ll quickly find the rules to live by. You missed a photograph because the card wasn’t properly formatted, so consequently you make a rule always to format your cards before beginning a shoot. The one time your camera runs out of battery power, you make it a rule that you never go to bed without putting your battery on a charger.

The choice to take care of those little things is not just an option, it’s imperative, because proper preparation prevents poor performance. It comes down to discipline. There’s a lot of discipline in photography, from knowing your gear to using it all consistently, but it’s all there to serve a singular pursuit: to get the photograph.

Aerial photograph of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

ISO 250 f/9 1/1600 60mm