Chapter 4. The Art of Sports

Divers in the 2008 Summer Olympics.

ISO 1600 f/2.8 1/1600 300mm

One thing that can really help make an exceptional sports photograph is research. And in the case of the Olympics, it includes looking at the work of other photographers.

It’s kind of an unspoken thing that we all do. We look at what everyone else is shooting, and we find the good angles because we don’t have time to find them ourselves sometimes.

So, over the weeks before shooting a sports event, you would examine the venue through others’ images and you would think, “Oh, that’s a great angle, let me try to find one when I get there.”

The idea is not to go and duplicate their image. If you do, you’re not really doing anyone any service. It’s kind of dishonest on your part, and you’re not contributing to the photography world.

I was scheduled to photograph volleyball on the last day of the Games, which included the final between China and the United States. I knew that there was one spot in the entire stadium that was dead center that had the Beijing logo. I’m not a big logo fan, but in this case I thought it would work. Trying to use words in photography is seldom very effective.

I got on the very first bus out to the venue and it was pouring rain, a real downpour. I just dashed to this location, and it is one of the times I brought only the equipment I needed. I had three lenses, including a 15mm fisheye in a small camera bag. I didn’t bring a laptop; I didn’t bring a long lens. I knew I wanted this image, and this image alone.

I also knew that if I had to drop off my stuff, someone could beat me to this one spot—the only spot in the stadium like this. I also knew that in the Olympics, once you leave your spot, you lose it. So I knew that once I sat there, I was going to live there for the next four to five hours.

It rained nonstop for the entire time. It just wouldn’t stop. And although initially I kept wiping the water off my camera and lenses, at one point I recognized that sometimes the greatest photographs happen by mistake, or when you accept the adverse conditions.

So I allowed water to accumulate on my 15mm fisheye lens. I set the aperture to f/16 and calculated the hyper focal distance to ensure that both the foreground and background were rendered acceptably sharp. So, I didn’t focus on the girls; I instead focused on this barrier itself, and used the depth of field to render the overall image sharp, especially the water droplets that were collecting on the front element of the lens. I patiently waited to use those droplets as part of my composition during the final.

Five minutes before the match, a Russian photographer walked up to me, looked at the water on my lens, picked up a wet sandy towel, and said, “Oh, no good, no good,” and started to wipe these perfectly accumulated water droplets off of my lens. We nearly had an international incident right then and there.

I let it go. I wiped it clean, and waited almost the entire match for the water to accumulate again in that way, then shot a few frames, getting the shot I’d waited all those hours to capture.

This image is all about layers. You’ve got a foreground, middle ground, and background layer, ideally. You know where you are: you’re in Beijing in 2008. You can see it’s a volleyball court. You can see the players. And what makes this image special is that the unexpected foreground element. How often do you see water droplets in a photograph? It’s pretty rare. But the droplets also convey that the entire match was played in the rain—it’s both factual and visual.

It’s an image that goes right back to marrying the aesthetic with the content.

USA’s Kerri Walsh and Misty May-Treanor win the gold medal in the Women’s Beach Volleyball game against China. The game was played in the middle of a downpour, but not delayed.

ISO 640 f/22 1/50 15mm

Sports Beginnings

I got into sports photography pretty haphazardly by working at my college newspaper, the Daily Northwestern. The biggest thing at Northwestern, as at most college campuses, is football. I started photographing football my freshman year. But the reality was I didn’t even know what a first down was. I was a European kid. I had no clue about football. But I had the ability to manually wrack focus and keep the player sharp better than most people. This was before autofocus, so that skill was invaluable.

This was when being a sports photographer was a really sought-after skill because not many people could follow an entire action sequence and get sharp, well-exposed frames. Keeping someone in frame, let alone in focus at f/2.8 using a 400mm lens was no easy feat. I don’t know where the ability came from for me, but it was there.

Though I knew nothing about the game, I watched people around me. I looked at the photographs in the Chicago Tribune and the Sun Times’ every week because those photographers went to the same games I did. I saw how they shot versus how I was shooting, and tried to narrow the gap. I studied them like a hawk and learned that your position relative to the action and your lens choice were critical. I learned to anticipate, and recognized how invaluable that ability was for photographing sports.

Creating great sports photographs is ultimately all about anticipation. You come to realize that for every single moment for every single play in football, there are four likely outcomes for the quarterback. There is a chance of a fumble, which leads to a turnover; a sack, which is a big moment in the game; a simple hand-off to the running back; or a long throw for a 10-yard gain or a touchdown.

So you generally start with the quarterback. Watch his eyes. Figure out where he’s leaning, and then you have to decide whether you’re going to stay on the quarterback or the football. It’s very formulaic. You can start a game and spend the first 15 minutes with the quarterback. Once you have enough stock of him, you then go to the running back and the wide receivers. You have to feel the game and have a sense of how it’s going.

If the team isn’t making any forward progress, you stay close to the quarterback, because it probably means defense is doing well, or the offense is doing poorly. If this is a team that’s known for throwing 20-, 40-, or 50-yard touchdown passes, you stay farther away from the quarterback and get those amazing catches.

ISO 800 f/2.8 1/640 45mm

Sprinter Usain Bolt of Jamaica sets a new world record and clinches his second gold medal in the Men’s 200M final in the 2008 Summer Olympics.

ISO 1000 f/2.8 1/000 400mm

The Apex of Emotion

This is Usain Bolt winning the 100-meter final in the Beijing Olympics. It’s a race that lasts less than 10 seconds, and I got there 12 hours ahead, which is insane.

What I was looking for in this image, which was shot with a 400mm lens wide open at f/2.8, was just Bolt and his pure joy at winning. The challenge as a photographer is capturing that spirit without cutting off his limbs and or having a distracting background.

To his left was a gang of photographers, and to his right was a big space-telescope–looking television camera. So I was composing as tight as possible to isolate him and make him pop right off the page.

The tricky part was I was using a fixed focal length, so I was calculating the best possible spot where he would likely react to winning. In a 100-meter final, an athlete often reacts a quarter of a second after they’ve crossed the finish line because they take a quick glimpse at the scoreboard to see their time. They might see that they’ve broken a world record, and boom, they instantly react.

On the other hand, after a 10-kilometer race they might collapse immediately or walk a few hundred feet past the finish line. And so again, you make a choice and you make a gamble, and you hope it pays off. In this case, he slowed down and started celebrating immediately.

So, that’s what you always have to be ready for—the unpredictable. Here he’s at the height of his reaction. I like the fact that the guy who is clearly 5 yards behind him is out of focus and not distracting, but you still see a big smile on his face because he has won the silver or bronze. It gives the photograph a little more context, that even winning second or third place is a momentous occasion.

Tsuboi Bustavo of Brazil (bottom) and Peter-Paul Pradeeban of Canada play table tennis in the 2008 Summer Olympics as seen in this long-exposure photograph.

ISO 50 f/10 0.300000s 300mm

Finding Order in Chaos

Sports are incredibly chaotic and unpredictable to the average person. The reason we go see a sporting event is that no one knows who’s going to win, or when the game-winning touchdown or decisive turnover is going to be. That’s what makes it exciting.

As a sports photographer, though, you need to break sports down in very formulaic ways, and know what all the options are. What can happen? You have to dissect every single sporting event you photograph very methodically, whether it’s a batter’s swing in baseball or a serve in tennis.

Tennis is an especially good example, because it’s a sport that is maddening to shoot with a fixed lens. The players move around the court like crazy. But you learn to study the athletes and see that they have a very characteristic serve, or forehand, or backhand. And you need to figure out the best position and what the best lens is for these shots.

When photographing tennis players, you know they’re always going to serve on that line on the right side of the court. There’s not going to be much variation there, and you find the perfect angle. And you can shoot the entire game just trying to follow the action.

You can refine your choices by deciding that you’re not going to spend much time on a forehand shot if this guy’s known for a great backhand. You’re not going to spend much time on her serving if she’s not known for her power in serving. You’ll spend more time waiting near the net if you know that these two athletes like to come in very close, as was often the case with John McEnroe and Björn Borg.

You have to study the sport and know it. What makes a great photographer of tennis is someone who gets great images of the initial serve as well as the backhand and forehand within five minutes of the competition, and who can sit back for the rest of the match and wait for the special moments that are unpredictable.

Handling the Stress

Photographing sports forced me to study things and dissect them like never before. And I learned from some of the best sports photographers at Allsport, which has now become part of Getty Images.

We would go to the track or the field the day before and study the light. We wouldn’t take a single picture, but just observe how the light changed around the course the entire day, from sunrise to sunset. This allowed me to plan the specific spots where I would position myself during certain times of the day, to take advantage of a certain quality of light.

Sports also made me very comfortable with long lenses, and with shooting extremely tight. Any mistake and you’re out, whether it’s focus or framing. Any wrong move, you’re done. That approach really influenced my aerial photography and most of my photography in general. So when I have a 500mm in my hand, I’m as comfortable as most people are with a 50mm.

It also helped to accept the fact that I would often have only one chance. It’s probably the biggest factor in photography, across all fields, more so in sports, but especially in photojournalism. There’s a tremendous amount of pressure that comes with that reality and it can lock you up mentally. It can completely destroy you.

Your heart starts to beat like you’re running a marathon. You become faint and you can start to shake, given the amount of pressure on you. At a certain point in your career, you realize that you’re cooked if you’re feeling that way. But what you need to remind yourself is that this is one of 10,000 swings you’ve already shot this year. Don’t worry about the significance of it right now.

Keep your emotions cool and collected, as well as your mental state, and treat it as if it’s just another swing. Just shoot it, get your picture, and block out all of the emotion.

The danger for me was I became so good at this, that I would equate it to being a sniper or a hired killer. I learned to utterly block out every emotion.

But the result was that it removed all emotion from my photographs. It made me a very effective sports photographer because I rarely missed the shot that would be prominently published in the paper. I could capture all these photographs, but emotionally I was dead, and I learned that I had to be careful about that. You can’t go too far in that direction. You’ve got to have a little bit of life left in your images.

Michael Jordan flies underneath a basket as a group of Atlanta Hawks looks on during Jordan’s last season with the Chicago Bulls.

f/2.8 1/500 80mm

Background Awareness

Background is incredibly important for a great sports photograph, perhaps more so than with any other genre of photography.

This is because the actions in any sport are pretty repetitive. It’s a batter at the plate; it’s a tennis player hitting a serve. These are actions that happen over and over and over again. You’ve likely seen them a thousand times.

So, what you want to do is isolate that action and consider the choice of the background. You often have three things that you can do with the background.

The first choice is to shoot wide and embrace the background because it is either beautiful or informative. You might make this choice because the fans are booing the player or jumping in the air. The background might include the scoreboard, or the lights that make it look grandiose.

Another option is to go the polar opposite and shoot extremely tight because the background is distracting and you need to blur it out. This was the case with the old Shea Stadium, where they had orange seats that made for a horrible background.

The third option is somewhere in between. It’s kind of a no man’s land, and harder to pull off. But, just as you would include or exclude anything in your framing of any subject, you can make choices for depth of field in shooting sports. The single most common approach is to go as tight as you can without risking cutting out part of the player’s body or part of any crucial element, such as a bat. The tighter you go, the harder it is to focus, the harder it is to find all action, and the harder it is to capture.

It’s very unpredictable. If you go too tight and something incredible happens, such as a bat breaking, the broken bat is out of the frame. But if it’s just a regular everyday swing in very bad light, it pays off to go super, super tight, because literally, things start to look different.

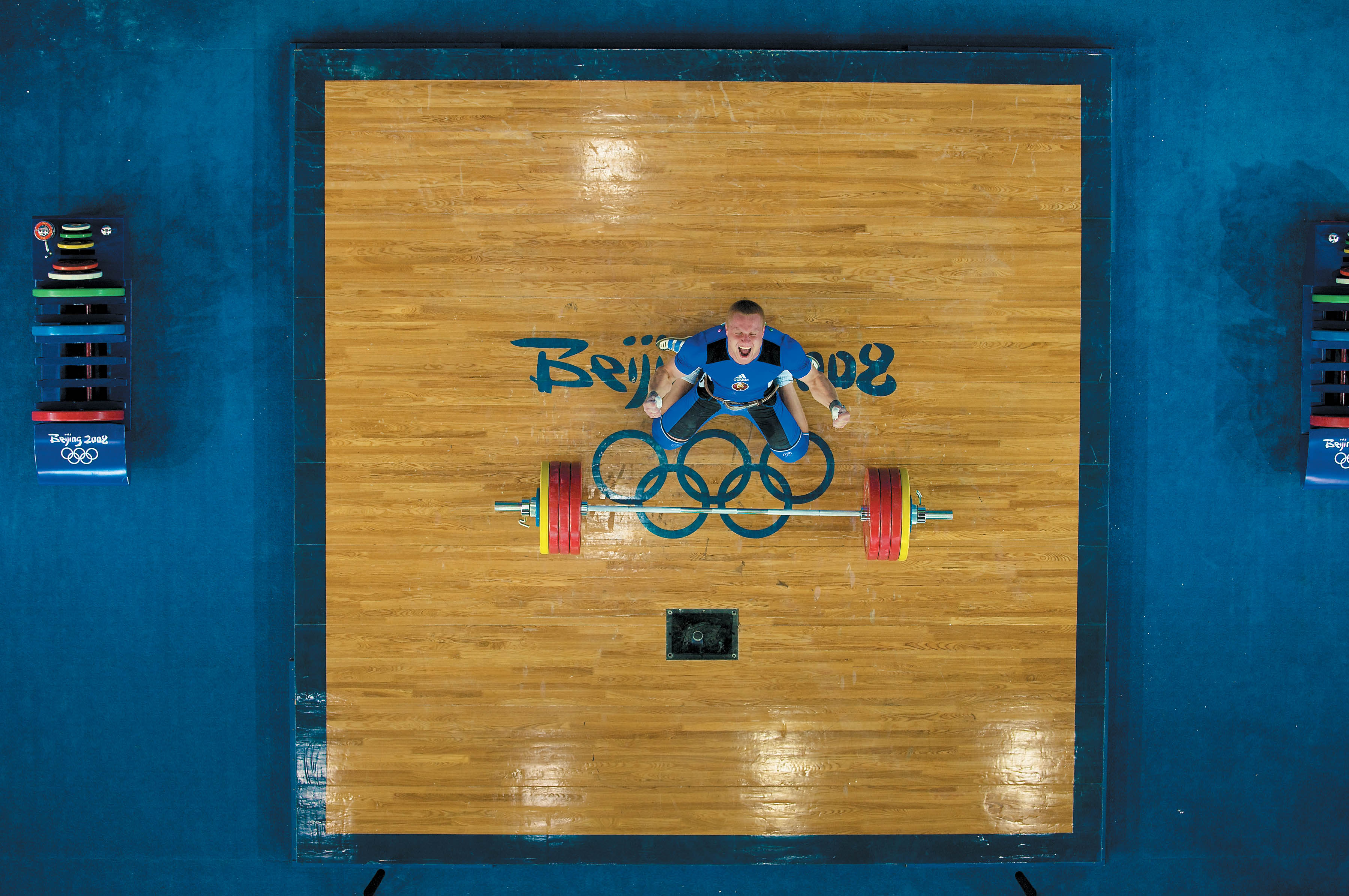

Weightlifter Andrei Rybakou of Belarus wins the silver medal and breaks the world record with an 185 Kg snatch in the Men’s 85kg Weightlifting competition.

ISO 640 f/4 1/320 73mm

The Men’s final of the 10 meter diving competition in the Summer 2008 Olympics.

ISO 400 f/2.8 1/400 45mm

A Telling Moment

This is an example of when the best choice was to go wide. Though you can’t really see it, the background was full of reporters wearing different colored shirts and typing on laptops. With a telephoto lens, the background would have looked ugly.

Fluorescent lighting illuminated the venue, so most people were shooting pans at slow shutter speeds. The background was too ugly to freeze the athlete mid-air and still make the image work.

I went to the extreme and used what most people would have considered dead space in the composition. I used a tilt-shift lens and maximized the tilt so that only the center focal plane was in focus. Everything at the top and bottom went out of focus. It’s pretty carefully composed, in that the flags are at the top of the frame with the three lights. The rule of thirds absolutely applies here.

Then I just waited for the diver, who would go on to win the gold medal, to dive off the board. It’s a very balanced picture, and the decisive moment is him arching his back as he leapt off the diving board. This photograph helps provide a sense of scale and reveals what a very dangerous feat this is. You don’t appreciate that with a 400mm-lens shot.

You appreciate how small he is, given the size of the venue, and you start to calculate the distance from his body to the water. It gets you thinking a little bit. It also gets you to think about him just releasing—letting go. It’s like the ultimate leap of faith.

Making the choice of how to handle the background frees me to capture the key moment, the “sustentation moment,” in a single frame.

This photograph helps provide a sense of scale and reveals what a very dangerous feat this is. You don’t appreciate that with a 400mm-lens shot.

The Sustentation Moment

The sustentation moment is an apex, or top, of a curve. When you throw a tennis ball up, it stops at a certain point on the curve before it reverses direction. This is a fantastic illustration for shooting sports at slow shutter speeds, where you don’t have enough shutter speeds, because it’s at that moment at the apex of the curve where things freeze.

It’s actually very easy to judge, as you’re shooting, where an athlete leaps up, stops momentarily, and comes down; you’re basically waiting for that moment. And that’s what that frame is. It’s just studying the motion.

The image of the diver on the previous page was made using a single frame, because I learned that when shooting in the continuous-burst mode, this peak moment would sometimes happen between frames, even when firing at 10 frames per second. When you are shooting continually, you can’t pay attention to your composition, and you can’t really anticipate the moment. And there’s really only going to be that one moment.

It’s actually very easy to judge, as you’re shooting, where an athlete leaps up, stops momentarily, and comes down; you’re basically waiting for that moment.

USA’s Michael Phelps wins his 8th gold medal in the 4 X 100 meter relay race (2008).

ISO 2000 f/5.6 1/640 800mm

China’s Liang Huo competes in the Men’s semifinal of the 10 meter diving competition in the 2008 Summer Olympics.

ISO 1250 f/2.8 1/2000 300mm

I knew I wanted to completely isolate that background and blur it out. I shot it wide open on a 400mm lens, which also allowed me to use the fastest shutter speed possible to freeze the image of those water droplets.

Paying Attention

During the Olympics in Beijing, it had been overcast for over two straight weeks. Day in, day out. During that entire time, I carefully evaluated different venues and how they might look differently should sunlight decide to make an appearance.

So when the first day of sunlight came, I already knew the kind of image I intended to make. I knew I wanted to completely isolate that background and blur it out. I shot it wide open on a 300mm lens, which also allowed me to use the fastest shutter speed possible to freeze the image of those water droplets.

This image was shot uncomfortably tight, because that’s just the way I wanted to do it at that time, and I was bored with loose images. My assistant, who was to my right, shot the same image with a 200mm lens, composing with more room around the athlete. He also nailed the moment and won the award for college photographer of the year that year. His images captured the same moment but it wasn’t the same image. It does make a difference when you go uncomfortably tight and really blur out that background.

The Unusual Background

This is the winning point for the gold medal in wrestling. On the ground level, the background was made of television cameras, referees, and fans in stands. It was ugly.

So I had to go overhead, which gave me this gift of yellow, blue, and red concentric circles. These are also storytelling elements in that once a wrestler drags his opponent out of the circles, that’s how he scores. The match and the image would be pretty boring if it all happened in the yellow area.

What’s really interesting about this image is you don’t know whose legs belong to whom and you’re not sure who’s who. Most important, you certainly don’t want to be the guy who’s on the bottom with his head down.

It is a beautiful geometry with the colors and the curves, and the repetition of those patterns and their shoes. It’s red and blue uniforms, it’s red and blue lines, and it so happens to be the gold medal–winning move. It’s an incredible dichotomy between beautiful, quiet lines and colors, and the chaotic spaghetti of limbs that captures a key moment, which happens in a split second.

For the athletes in that second, either they’ve lost the gold medal or they’ve won it. This photograph speaks to how everything is so beautifully set up, from the venue to the uniforms, but in the end the reality is that there is only going to be one gold medal winner. To these guys, it’s chaos; one wrong move and there goes the medal.

As the photographer, I only had two athletes to work with, but what I was really aiming for was the right geometry and color palette. I had to find that right elevation, so I wasn’t so low that I caught a distracting element in the background, or so high I couldn’t see their faces. I had to find the perfect balance between being too high or too low, and too tight or too loose.

It feels electric to witness a moment that is so dramatic and even historic. As a photographer, you are going to see 20 or 100 moments like that in your career. The majority of people experience that excitement through a television, but as a photographer you get to feel the thrill in person.

When you physically feel the vibration of the cheers and pure joy of 20,000 people or more around you, it’s hard not to get emotional about it. There is nothing in the world like it. It’s something you never forget.

Andrea Minguzzi from Italiy wins the gold medal during the sixth session of the Men’s Greco Roman Wrestling competition in the 2008 Olympics.

ISO 1000 f/3.5 1/1000 300mm