Chapter 9. The Art of Lens Choice

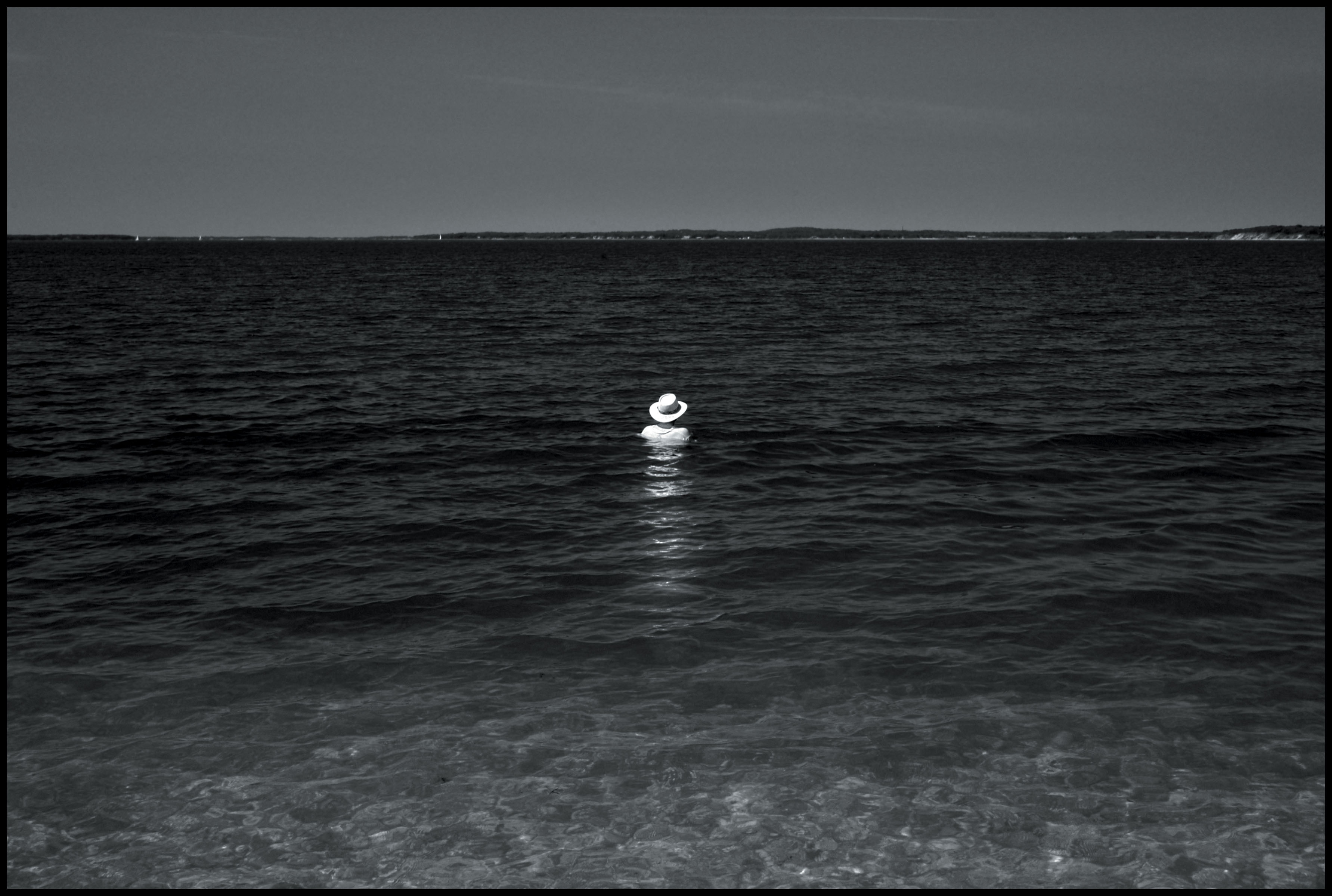

Lens: “Little Black Box,” Sag Harbor, New York (July 2007).

ISO 320 1/500 26mm

The reality of photography is that there are always infinite possibilities in front of you. And if you think you’re probably missing a million photographs every time you take one, it is easy to feel overwhelmed. This makes lens choice even more of a consideration.

There will be times when you choose a wide-angle lens and then, for example, you see an image on top of a hill that would require a 600mm lens, possibly one of the best images you’ve ever seen, but you made a conscious decision not to bring that big lens because of its weight. You can’t kill yourself over that choice, because the alternative is to become a walking equipment closet. With that much weight, you are immobilized. You get tired, and then you just get lazy. You just have to accept that you’ve missed that shot and that’s OK.

Part of the discipline of photography is asking the question, “What do I really need?” To answer that question, often you first have to ask yourself, “What am I looking for? What is my vision for the photograph?”

Learning Lens Discipline

One of the best things that shaped my career was that I didn’t have a lot of money when I started photography, and all I had was one camera with a 50mm lens. I didn’t have access to the zoom lenses that I have now, so I was forced to learn how and when a single focal length would work and when it couldn’t. It forced discipline.

I used a 50mm lens for this image of an opium smoker. It was for a photo essay on how drugs and the drug world financed the Taliban in Pakistan. You can’t ask for more striking symbolism, a man smoking himself to death in front of a tombstone.

The choice to use the 50mm lens was based on my desire to get a sense of place. Had I shot this with a telephoto lens, I wouldn’t have been able to see the moon or much of the cemetery. Everything in the background would have been blurred, and the overall composition would have been too tight. Had I shot with a wide-angle lens, the foreground and the setting would have dwarfed the background.

With a standard lens, the scene appears as it would to the human eye. You can see the mountain, the moon, and the graveyard. It gives the composition an important sense of balance.

When you make a conscious decision about a focal length, you are deciding what to include or exclude from the frame. You are composing an image with nothing extraneous in the frame that would distract your viewer from what you are trying to convey. At the same time, you don’t want to make the image so tightly composed that it cuts out relevant information.

Opium smoker in Quetta, Pakistan, 2001.

When you use a fixed focal length or even a zoom at a specific focal length for a period of time, you’re forced to learn the sweet spot of every lens and where it fails. You discover when it’s going to be too tight and when it’s going to be too short. You quickly get a sense of what the focal length is going to give you even before you’ve raised it to your eye.

The Power of Perception

Lens choice is really about depth perception. It’s about understanding that a 14mm lens can make a small room appear gigantic, or that a 300mm lens can make two objects appear closer to each other than they actually are.

One of the principles that I haven’t heard too often, but that informs much of what I do with my photography, is not to make a lens choice based on how far my subject is or how wide or tight I want to shoot. I choose a lens based on compression, how the lens impacts the relationship between the foreground and the background.

If I want to create the impression that the foreground and background are closer to each other than they may actually be, I choose a longer lens, to at least a 200mm.

For this image made aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, I knew that the telephoto lens would make it easy to create a very clean, graphic image. By some slight adjustments to my camera position, I was able to isolate certain key elements, while blurring others out.

There’s nothing to look at in this image except for the group of guys, the pilot, the setting sun, and the plane. There are just those four elements. There are no potential distractions at the edge of the frame. It’s extremely clean and graphic.

However, it is the compression provided by the telephoto lens that makes this shot possible: those four elements appear to be closer to each other than they really were, thus creating a relationship in the viewer’s mind.

It looks very much like a painting to me, because the composition is so clean and there are no distractions. It’s what you could call a very commercial image, because there is just no messiness to be found in it.

The USS Abraham Lincoln at sunset (2003).

ISO 100 f/8 1/125 190mm

That’s the real issue with the ultrawide-angle lens: distortion. It can be your friend or your enemy.

With a wide-angle lens, you would see everything, including all the mess that was on the ground. If I had made the image with a 24mm lens, this would have been a very different photo.

Where a telephoto lens creates compression, a wide-angle lens creates a different kind of distortion between the foreground and the background. In this image of two men working on the antenna atop the Empire State Building, I was shooting with a 14mm lens.

You can see the antenna expanding through the frame toward the top and bottom, and it’s made to seem enormous when in reality it’s only about as wide as two human arm spans. In the frame with a wide-angle lens, it looks humongous. The foreground is tremendously exaggerated.

Just below the crewmen is the 110th floor; the observation deck and the tourists there appear as nothing more than specks. Even the surrounding buildings around these men appear smaller. That’s obviously not a realistic representation of scale.

And that’s the real issue with the ultrawide-angle lens: distortion. It can be your friend or your enemy. If used incorrectly, it’s incredibly unflattering. If used correctly, as in this case, it makes the image more dynamic. You can see how the buildings look as if they’re out of a pop-up book. Obviously, the buildings on the edges of the frame don’t actually lean over. They’re not the Tower of Pisa.

The reason this image works and why others might not is that it has a visual anchor; in this case, the two engineers. An anchor has to be pretty close and become a substantial part of the frame in order to make itself relevant and to work.

The challenge here is that because you are so close to your subject, if the subject moves a half foot toward or away from the camera, it suddenly becomes too big or too small in the frame. As a result, you have to be very nimble with a wide-angle lens, because of its ability to focus the attention of the viewer on the subject or foreground element and to play with that sense of scale. You quickly start to understand why it’s such an important creative decision.

Workers repair the antenna atop the Empire State Building in 2001.

ISO 200 f/5.6 1/1000 14mm

Swimmers on the Santa Monica beaches at sunset.

ISO 100 f/3.5 1/6400 24mm

Bag of Tricks

The reality of shooting photojournalistically is that a lot of the stuff that we shoot isn’t always very graphically interesting. A lot of what we shoot is part of the everyday, and sometimes it’s just not pretty, not very geometric, not that aesthetically pleasing. My solution for that is often found in my lenses, my little magic tricks.

These lenses allow me to create geometry out of the stuff doesn’t naturally pop out at me.

When you see a painted wall with two red circles and a woman in a yellow dress walking by it, it doesn’t take a genius to see the geometry in that. But when you are faced with an everyday street scene, there is rarely a lot of clean geometry. Instead it’s often busy and chaotic.

Using a wide angle allows you to find the geometry, but it also lets you emphasize that element or subject in the foreground. In fact, you can even use that wide-angle lens to hide a distracting element in the background right behind the subject, if you are close enough to your subject. You can’t do that with a telephoto lens, but by using a wide aperture and a limited depth of field, you can blow out the background.

One of the tricks that a photographer has to practice is simply moving around. Whether you are using a wide-angle or telephoto lens, you need to adjust your position constantly as you look through your viewfinder to discover and force that geometry into your images. You are constantly looking to emphasize and de-emphasize all these disparate elements within the frame.

So, if I am shooting with a 35mm lens and I take a half step to the right, the foreground elements remain relatively the same, but the background changes quite a bit. I find myself constantly dancing around and finessing things as a photographer, trying to make all these elements line up in some sort of geometric way that adds meaning.

It’s something that I find much easier to do with a wide-angle lens, and when that doesn’t work well, I will often revert to a telephoto lens.

Zooms versus Primes

Zoom lenses for me are a convenience. It’s nice to be able to walk out with two cameras and two lenses and know they will cover every single range. Having to change lenses, especially when you’re in a new and fast-paced situation, can cause you to miss a lot. But when you’re walking around with a 24–70mm and a 70–200mm, you can cover the world with just those two lenses.

With those two lenses and two cameras, you don’t need the camera bag anymore. All you need are your memory cards and extra batteries, and you’re good to go. With prime lenses, on the other hand, you have to carry as many as you need, and the idea for me is never to travel around with more than three or four lenses if possible. If I am walking around with too much equipment, it just gets too heavy and cumbersome.

That being said, some of my best work has been shot with prime lenses, because after having done this for more than 20 years, I am very familiar with how prime lenses perform and what they offer me. I know their sweet spots.

It’s important to learn the sweet spot of your lens, particularly a zoom. What I often do with my students is have them put gaffer’s tape on their zoom lenses and force them to shoot at a specific focal length for two weeks. They are not allowed to move it. They are forced to learn the sweet spot of that particular focal length on that lens, as well as discover when it fails.

Lensing As a Practical Choice

I used an 18mm lens for this image of a homeowner returning for the first time to his home in the Lower 9th Ward in New Orleans. It was a full year after the storm had hit and the levees had fallen, and it was only now that he was able to return to salvage what he could, which was nothing.

I was very physically limited while making this shot. I could only go so far back, thus forced to use a wide-angle lens to capture the scene.

Louis Simmons came back to his home for the first time since his rescue three days after Hurricane Katrina struck (August 2006).

ISO 640 f/4 1/10 18mm

So I had to use a 16mm lens to capture this very small room. The same image with a 50mm lens would have resulted in a very different photograph. With a normal lens of that size, you could never get the sense of all the content in that small space. The 50mm would produce a very limited field of view, and you would just see the man. I would have probably lost the mirror and the fan on the floor. Most important, the photograph included the hole in the ceiling, which is the very opening out of which he had to climb in order to be rescued.

The wide-angle lens not only allowed me to include all that, but also helped me illustrate how dwarfed he was by the devastation around him.

Owning Your Frame

When it comes to choosing the lens and composition, I treat the frame as if I were painting. One of the first things I was taught when learning to draw was that you can’t just put your pencil on a piece of paper and start drawing. It’s what you want to do, but you shouldn’t.

When I simply started drawing, I’d get some fantastic results as I begin, but when I’d reach the edge of the paper, I realize I didn’t have the discipline to think about how the image would fit at the edge of the paper. When you reach the edge of the paper or the canvas, there’s really nothing more that you can do.

I think composing a photograph should be treated in much the same way. Those four edges and corners are ridiculously important, and you see how they are transformed and impacted by your lens choice.

The goal is to find a way to accept the limitations of the equipment or the situation and to begin engaging in the act of art. Each of us has to aim for that space between the technical and the artistic, where discipline and knowledge mix with talent and luck.

New Orleans: one year after Hurricane Katrina struck (2006).

ISO 200 f/5 1/320 24mm