Chapter 8. A Love Affair with New York

Times Square and Midtown Manhattan after dusk (2007).

ISO 1600 f/2.8 1/40 16mm

New York is my only true home in this world. From a young age, I’ve always been a traveler. I lived in Switzerland and Paris, but I have always considered New York to be my city.

I grew up there from the age of 5 until I was 18, returning as a young adult for seven years during my stint at the New York Times. So I’ve spent over 20 years—more than half of my life—in New York City. It was the only anchor I ever had in terms of a home and a family.

To me, New York is the center of the earth. It’s a city that seems to be a magnet for some of the most talented people in the world. I’m not sure you can say that about any other city. Paris is a romantic city. Rome is a historical city. I think Shanghai and Beijing will be bigger, but in my opinion, New York is the epicenter of the world in terms of creative talent.

And there I was in my 20s working for the paper of record in the world—the paper of the city, the New York Times. There was no shortage of challenges while working there, but I was very comfortable with what I did and what I shot, mostly because of the feedback that I got from the people who read the paper. My years at the New York Times were some of the best years of my career because I felt like I was documenting a town, a city. And I got feedback from readers on a regular basis that allowed me to appreciate that how I was seeing the city was resonating with my fellow New Yorkers and people all over the world..

Woman in Stripes

In 2007 I was walking the streets the same way I did when I was 15 years old, with only one lens and one camera. For seven weeks I went out with a Leica with a single lens.

I was just looking for New York moments and walking near the corner of Fifth Avenue and Central Park South when I saw this woman in stripes pushing a stroller. I noticed the pattern of the crosswalk that lay in the direction she was heading, and I ran at full speed after her, being careful not to run into her or scare her. I was only able to capture three frames.

I saw her and anticipated the moment, but I only had seconds to react and make the photograph. Thankfully, I captured one frame with her legs outstretched, emphasizing the stripes of her dress. It’s a messy image. It’s not perfect, but it works.

Once you see something like that, you can’t hesitate or decide not to make a photograph. As long as you’re not bothering the person you’re trying to photograph, you keep a healthy distance, and you don’t scare or startle her, you can fall into the vibe and make the photograph. She was never aware that I was there.

This is all about framing it, shooting it, and getting it. You can’t think it over too much. It’s not going to happen ever again, and it never did. Asking her to turn around and do it again was not going to be an option.

Exploring patterns of New York City’s street life in a 12-week column for the New York Times

ISO 320 1/750 28mm

Front Page Beat

Despite my visually graphic tendencies, I landed the front-page beat for the New York Times, which was often reserved for hard news events rather than visually pleasing images. So if there was no big story that day, or no great pictures to illustrate a story, it would go to an image of New York City. And between my aerial photographs and street photography, it became my beat for a full two years of my six years at the paper.

I had to find an image that spoke to the news of the day. If it centered on the weather or the season, the image had to illustrate that it was hot or cold, or muggy, or reflected the turn of a season. It couldn’t just be a pretty image. It had to be an image that either spoke to the climactic change, the time of the year, or the events of the season—whether it was a holiday or spring.

So I had to become very attuned to the city and what happened in it. And what ended up happening was, because of my graphic eye and the images I made, I discovered that I had a style.

The best letters from readers were rarely about my best photographs—I kind of knew which ones were good, and my colleagues would often tell me as well. The best letters were in response to photographs that I thought were terrible, or lacking. I realized that as a photographer, the true of magic of photography is that every photograph, every piece of art, means something different to someone else, and everyone connects to it differently. And I found that utterly fascinating.

Avoiding Cliché

The challenge I faced doing this beat for the Times was to photograph something that was recognizable enough that readers knew it was New York City. But it had to be photographed in a way that was aesthetically different enough to make it a unique image, not a cliché.

This is an image of a young boy playing in the water jets in front of the planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History. It’s a simple image, but I’ve always loved it because geometrically speaking, it’s a plethora of shapes and contradictions.

You’ve got this great structure with the planetarium and its perfect spheres of the planets. With this shot, you’ve got a very rigid, geometric world in the back contrasted by the very fluid body motion of the child.

To me it just feels very free, like what it feels like to be a child or a young man. Here he is playing with a jet of water, which was my favorite thing as a kid. And then you’ve got light and dark—the brightly lit spheres and shapes and building, and he’s in perfect silhouette. It’s a wonderful play on geometry, of light and dark, lines and shapes, gesture and movement.

The American Museum of Natural History (2007).

ISO 320 1/750 35mm

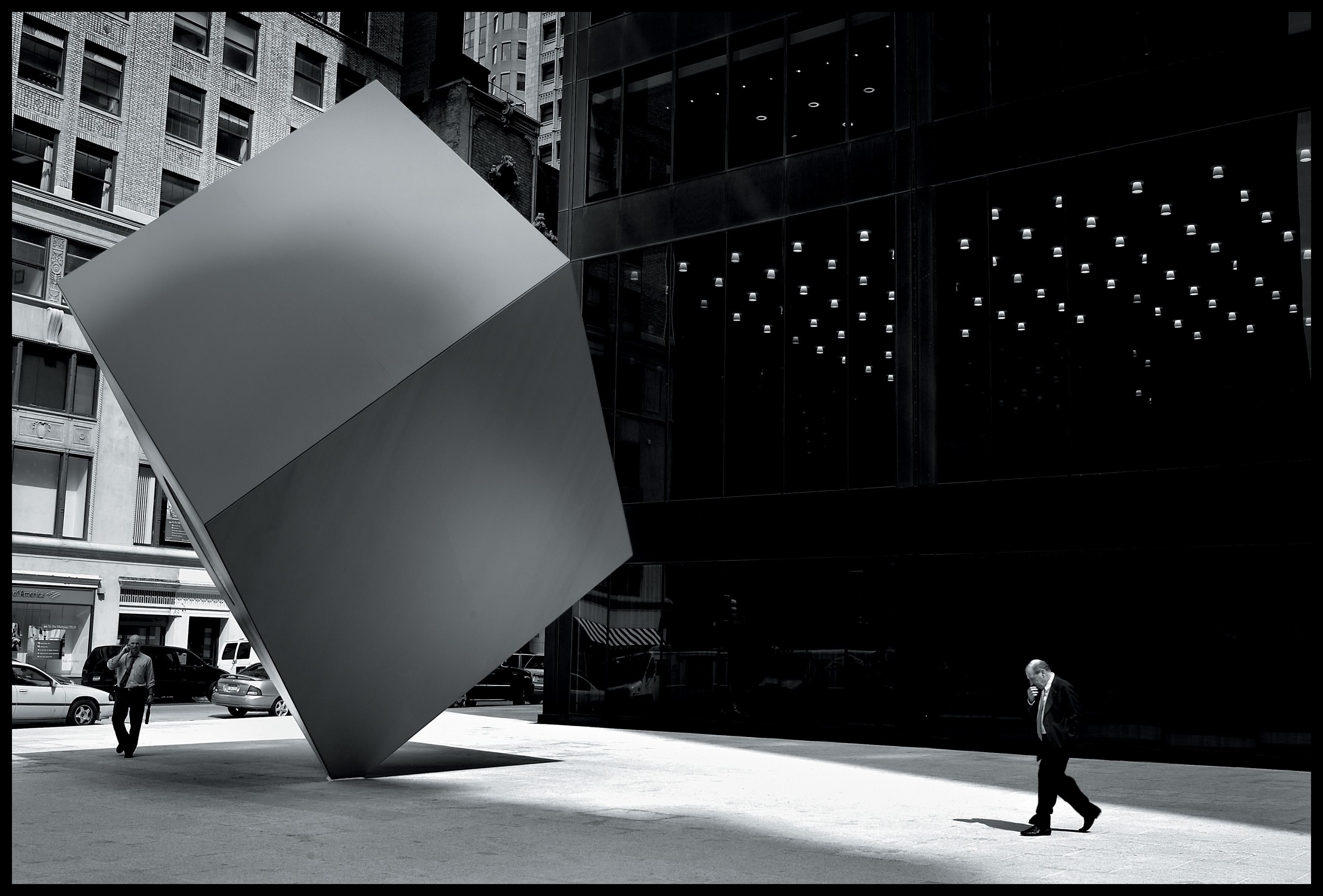

Financial district in New York City on July 30th, 2007.

ISO 320 1/90 28mm

Seeing Potential

I love this image. It was made on Wall Street during the financial crisis that began in the summer of 2007, and to me the cube seemed ready to squash the older man who’d probably had a very bad day, because everyone on Wall Street was experiencing bad days that week.

Then there is also the quality of the light and the graphic elements in the frame. There’s a shaft of light and the play between light and dark. There’s the beautiful pattern of the building’s interior lights. The building across the street has small squares in the windows, which visually repeat the shape of the cube. And then you have the guy on the other side of the cube, which helps balance the entire composition.

It’s very clean. It’s very simple. It’s all about geometry. It’s all about motion. Obviously, he’s not in a great mood. Looks a bit downtrodden. And thank God there wasn’t a hotdog stand in the middle of that frame.

The point with an image like this is that you see the potential for something and you just wait. That’s a lesson I learned from studying the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. There’s a famous image he captured of a descending staircase with a bike passing by in Hyères, France. I saw his original contact sheets. He shot 36 frames of the exact same composition, and only one of them included the bicycle.

A lot of photography is about finding that environment and waiting. In some documentaries of Cartier-Bresson, you may see him jumping around like a bumblebee taking pictures from every angle, but that’s what he wanted you to see. The reality is that he waited, and waited, and waited.

You find the right set of circumstances with the right light and geometry, and you sit, pray, and try to blend in. It’s like a hunt.

Just Make the Shot

This photograph was taken the same day as the previous image. They were made within an hour of each other, and again it was across the street from Wall Street.

This image is all about layers. The focus of the image was not primarily the kid looking up at the sky and the geometry of the shadow; the key thing that made this image work is the reflection of the stairs inside the man’s sunglasses. The repeating lines are everywhere, and the human beings appeared chaotic and dynamic within a very linear world.

When you’re in New York it’s such a chaotic environment. The only anchors in New York are those buildings. So when I’m doing street photography, I’m paying attention to the shape and lines created by those buildings and the way they cut off or reflect light. Those buildings served as my background but also informed my sense of geometry and composition.

Look at the geometry of the buildings in this photograph. Pretty much what I did as a photographer was compose my frames as cleanly as I could with those lines in mind. When the man with the sunglasses walked into the frame, it completed the scene and I made the photograph.

There’s just the right amount of motion with the man entering the frame. That’s why I think 1/125 second is the magic shutter speed when practicing street photography; it’s just a quick grab—click. 1/250 second freezes too much, and 1/60 second is too slow.

With moments like this, you just react. I think at a certain point you feel it. You just have to let your gut and your heart say, “Make the shot.” You can’t overthink it, especially in moments like this. You can’t plan these moments.

I was the happiest guy in the world photographing every day in New York, and people still talk to me and say things like, “The paper hasn’t been the same since you left. I miss the aerials of New York. I miss your views of New York.” And all I was doing was following a tradition of what photographers had done for decades.

It’s just that these days it’s less common to have kind of a love affair with the beauty of your everyday world. Granted, New York City is a mecca of sorts, but my goal as a photojournalist at the Times was just to see the inherent beauty in the everyday and to share that discovery with the world in a photograph.

Across the street from Wall Street, New York City, July 30th, 2007.

ISO 320 1/125 28mm