Chapter 12. The Paniolo

Big Island, Hawaii (January, 2006).

ISO 100 f/8 1/3200 100mm

The paniolo shoot in Hawaii had all the elements of a dream job.

I got the call from Canon; they were looking for a photographer to illustrate the brochure for their new Canon EOS 30D and said, “We need seven shots. You can go anywhere in the world. Here’s your budget.” It was one of the few times that this will ever happen in my life.

And while it had all the elements of a dream job, it was still an assignment, so there was quite a lot of pressure to decide where to go and what to shoot.

We decided to photograph the paniolo, some of the first cowboys in the history of Hawaii. We went to Waimea, on the big island of Hawaii, and I can tell you from experience that it is one of the few places that I would say is heaven on Earth, as well as hell.

A lone horse grazes at sunset in Waimea on the Big Island of Hawaii.

ISO 200 f/6.3 1/320 16mm

Window of Opportunity

Take it from me, never photograph in Hawaii in January. Although you’ll likely find the most beautiful light you’ve ever seen, you’ll also have to face the harsh reality of the rainy season, when it pours 80 to 90 percent of the time.

The “dream job” proved incredibly frustrating. There were many times I thought I was going to lose this assignment or come back with nothing.

When I made this image of the horse, it had been raining for three straight hours. It was yet another day of torrential downpour. This was one of the last of the scheduled shoot days. Pressure was high. Frustration was extreme.

I’d already shot as many pictures as I could in the rain, so I had exhausted that option. I had accepted the weather and just shot through it. But after a few thousand photographs of horses and people in the rain, I realized that this was likely going to be the biggest downer of a campaign ever.

I had considered other locations on the island, but quickly realized that even if the light was great when we left for the spot, it would likely be raining by the time we got there.

So I had to accept the fact that I couldn’t control nature. I just had to let it go.

Then I saw a little opening in the sky and we bolted for the four-by-four Gator vehicle. When you get that five-minute opening in the sky, you can’t be busy pounding the dashboard of the car venting your anger and frustration. You make sure your team is ready and you jump at the opportunity.

We drove following the light, which was nothing more than a patch of brightness hitting the mountains.

As we got closer to our destination, I saw the horse. It looked golden. The light was incredibly gorgeous because of all the cloud cover. The darkened sky accentuated the lush green grass that was the result of all those weeks of rain.

Two cowboys from the Kahua Ranch in Wamea ride their horses past a rainbow at sunset.

ISO 100 f/4 1/160 14mm

I used a wide-angle lens for the image because it allowed me to include the beautiful sky in the background. Had I shot this with a tighter lens, I would have compressed the horse into the background and lost the lovely quality of the sky.

I then looked behind me and saw the clouds moving swiftly across the sky. Suddenly we were racing down the hill, and I saw another shot.

I picked up my radio and communicated to the cowboys on horseback, “I need you to go from the bottom of the ridge to the top of the ridge.” I made them repeat the movement fives times. All the while the light was rapidly changing and retreating.

As it started to rain again, we rushed up the hill where I spotted a rainbow. The rain was collecting on the front element of the lens, but all I could do was wipe it away and keep on shooting.

In a little less than an hour, the window of opportunity for photographs with that beautiful light had closed.

When you get that five-minute opening in the sky, you can’t be busy pounding the dashboard of the car venting your anger and frustration. You make sure your team is ready and you jump at the opportunity.

A Commercial Approach

Even though this was a commercial assignment, it was my first one so I was very hands-off in terms of directing. I tried to make it as documentary as possible. With rare exceptions, I waited for moments to happen.

Today as a filmmaker, and as a commercial photographer, I would be much more controlled and plan ahead, with an entire team to pre-light and pre-think these photographs. And I would probably not have any of the stresses that I had back then.

I was just making the transition from editorial to commercial, so this editorial approach was my strength at the time—and I was right to do it this way. I would just let moments happen, capture them, and maybe say, “Do that again,” or “Let’s change it a little bit to this way.”

Now, instead of waiting to discover a moment, I’ll say, “I’m going to want a shot of him with his white hat and white shirt against the blue. Let’s make it happen.”

Now I know how to work both ways, and I can make a photograph look as if it had been shot spontaneously even if it’s completely constructed. Back then I didn’t know how to make a constructed situation look natural. I’ve evolved.

You have to learn how to make constructed situations appear natural because when you do a big commercial project, you have so many people involved. It’s extremely expensive, so you learn to accept that everything has to be planned.

You don’t have the option of thinking, “We’ll figure out what we’ll shoot when we get there.” That approach doesn’t work for a commercial shoot. You have a shot list; you have a location list; it’s been scouted. Nothing is left to chance. But to make the shots look unplanned, you have to develop the sensibilities of a photojournalist.

That’s the art. It’s a very fine line, and a very difficult skill to develop. I think sometimes it’s harder for people with a commercial background to do it, because they haven’t documented the real. But in some ways it’s easier for them because they know the exact pose that’s going to look perfect, whereas a photojournalist needs to feel it out and find it.

An aerial view of the volcanic terrain in Waimea on the Big Island of Hawaii.

ISO 100 f/4.5 1/500 24mm

Instead of placing the cowboys in the middle of the frame, I put them at the right third of the frame, and the result was a much more balanced composition.

Relying on Old Tricks

Here is a classic vista picture that uses one of my favorite tricks. On days with patchy clouds, you’ll see patches of light and shadow, and when your subject matters are in shadow—in this case, the two cowboys—they in effect become silhouetted. It’s a really cool technique to pull off.

Naturally when they were in the sunlight, the look was very different, but in the shade they became silhouetted. If I had opened up the exposure for the shade, I would have blown out all of the beautiful color around them. In this case, I exposed for the highlights—the lit areas—and allowed the shadowed areas to turn utterly black.

I also used the rule of thirds for building the composition. Instead of placing the cowboys in the middle of the frame, I put them at the right third of the frame, and the result was a much more balanced composition.

I shot this image with a 16–35mm lens, which allowed me to get this incredible panoramic view. I also shot everything in manual mode, not autoexposure, so the cowboys would be silhouetted.

Shooting with a zoom was a practical choice because I couldn’t keep up with the cowboys on foot, and instead had to be driven around in the four-by-four while standing with my head poking out of the sunroof. The zoom lens allowed me to make those small but critical last-minute changes.

Two Hawaiian cowboys ride their horses through wide open ranch land.

ISO 100 f/10 1/250 16mm

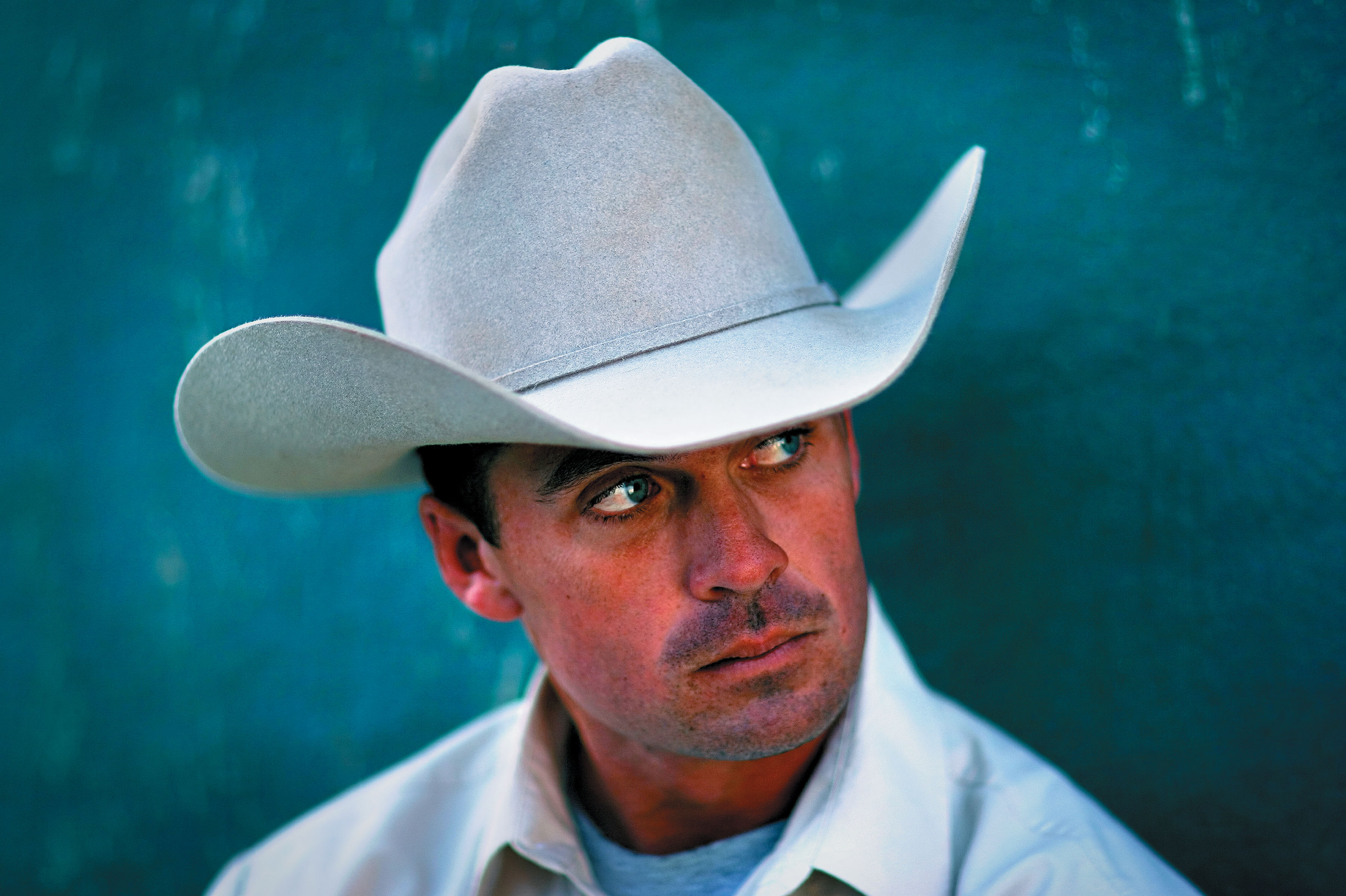

A portrait of a Hawaiian paniolo in Waimea.

ISO 100 f/1.2 1/640 85mm

Back to Basics

To make this portrait of one of the cowboys, we went back to basics. As I do for many portraits, I kept it simple not only in terms of how I shot it, but especially in terms of wardrobe.

I had my subject in a white hat and a white shirt against a simple blue background, and I shot with an 85mm f/1.2 lens wide open. It is one of my favorites of all the portraits I have ever taken, and the lighting setup couldn’t have been simpler.

It was an overcast day; we had a big white reflector and all natural light. I didn’t need to have fancy lights or lots of equipment to make this portrait. I just had to focus on making it unique by simply art-directing the clothing and the background, with the added bonus of the color of his eyes matching the color of the background. It all came together.

Because I was using the 85mm f/1.2 lens wide open, I had to be critically accurate with my focus. I didn’t have much latitude with respect to depth of field.

Although my cameras have multiple autofocus sensors, I choose and detect focus using the one autofocus sensor that is positioned closest to my subject’s eye. With the lens wide open, the depth of field is incredibly narrow, and it is not possible to keep both eyes in focus.

As I do for many portraits, I kept it simple not only in terms of how I shot it, but especially in terms of wardrobe.

Aerial view of cattle in Waimea, Hawaii.

ISO 100 f/4 1/1250 200mm

If I had shot into the light, I would have gotten a very different result than if I had shot with the light behind me or off to the side.

Understanding Your Light and Lens

This shot was made from a helicopter at sunset. One of the most important things to keep in mind in photography is where you are relative to the light source. During a sunset, the light comes from a constant position; if I had shot into the light, I would have gotten a very different result than if I had shot with the light behind me or off to the side.

We shot toward the setting sun that created an incredible glow, when these cows started running away from the helicopter and the dust started to pick up. This is known as the “V nature,” the geometry in a picture that kind of draws your eye in an otherwise unspectacular image. These little elements between the backlight and the V nature of that geometry make for a much better image.

By using a 70–200mm lens at the 200mm position, I was able to take advantage of its compression at that focal length and accentuate the V the cows were making as they were running away.

Always Look for the Closer

For almost any series you work on, I recommend always trying to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. As you get more advanced, you can begin to break down that formula, but when you’re getting started, always try to have a basic structure to ensure you tell a complete story.

This photograph is an example of an ending image. Being a cowboy has this very mythical aura about it, and the reality is it can be a very lonely job. Here he is at the end of the day, the cowboy by himself, bringing the horse back to the stables. I shot it very backlit, with an 85mm f/1.2 wide open, to create a very lonely, dark mood that I think is crucial for this series.

One of the most important lessons that any photographer who has been doing this for a while will tell you is that you need a lot of patience, and you can never give up. When the situation looks dire—and that was the case at different points with this job—it’s important to stay ready and be prepared to make it happen even if the moment of opportunity is brief and fleeting.

On this shoot, as with many others, fear was the number one enemy: fear of failure, fear of creating a boring image, fear of missing the moment. Learning to manage those fears was and is a constant struggle. But as this assignment demonstrated, I couldn’t control everything.

The irony is that when I started to accept that I couldn’t control everything, I started taking chances. I rolled the dice even further and achieved a higher degree of success. When I was ruled by fear, I played it safe and my images suffered for it. It’s when I overcame my fears that I started to become a better photographer.

A cowboy takes his horse into the stable at the end of a long day.

ISO 640 f/1.2 1/80 85mm