Introduction

Workers repair the antenna atop the Empire State Building in 2001.

ISO 200 f/5.6 1/1000 14mm

I have been given a chance to witness and experience many different lives, occupations, and realities, thanks to the many generous people who’ve allowed me to document them with a camera.

I have hung from the needle of the Empire State Building, nearly 1,500 feet above New York City. I have witnessed the launch of the Second Gulf War from the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier. I have seen people uprooted from their lives in Afghanistan, and witnessed Americans devastated by the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.

I have photographed a U.S. president in the White House in the morning, and, later that very afternoon, a homeless man on the street. I have photographed major sporting events including the Olympics, the Super Bowl, and the World Cup.

But some of my favorite moments in photography—of my career—have been the intimate moments spent with everyday people. Granted, some were Nobel Prize winners, industry titans, or billionaires, but others were fascinating, regular people from small towns or villages who made tremendous contributions to their local community—or sometimes simply to their loved ones.

Most of the time, human beings are extremely complex. I have witnessed some of the very best of humanity with my own eyes, and some of the very worst behavior imaginable, as well.

Photography has given me the opportunity to be in awe of a child reacting to being photographed for the first time. On the other end of the spectrum, I’ve witnessed the joy on someone’s face when they make a great photograph of a flower or of the game-winning touchdown and realize they’ve captured that moment for eternity.

That is the ultimate beauty of photography, as with any art: its ability to make us very happy.

One of the most important photographic lessons I learned came from my father, Bertrand Laforet, who is also a photographer. I was 16 years old, sitting in his office at a magazine in Paris. He walked in and looked at me.

“You know what I love about photography?” he said. “I’ve been doing this for close to 30 years now, and every day I still learn something completely new.”

My father was referring to the endless world out there for photographers—and the endless opportunity to learn, to take chances, to experiment. I never forgot those words. I came to understand what he meant, and did my best to live and practice photography accordingly.

A surfer makes his way into the water at sunrise at San Buenaventura Beach in Ventura, California.

ISO 50 f/100 1/100 500mm

This book is meant to be a collection of some of my most successful images from my career that has spanned nearly 18 years. On the DVD that accompanies the book, I discuss some of these photographs and others in greater detail in over 60 videos. The book and DVD come at an interesting time for me, as I am starting to focus almost exclusively on being a director.

That being said, my first love will always be the photograph. I find it to be one of the purest artistic pursuits. The artist is always held back by reality in some ways (by what he or she can actually photograph, Photoshop excluded) but is also challenged to produce a work of art and to push creative boundaries to new levels.

One of the things I discuss in the book is technique. I believe that just as a musician must learn her scales before tackling whole works of music, a photographer must master the basic technical aspects of photography in order to create works of art. Technique doesn’t generally lead to great photographs, but poor technique can prevent a photographer from creating great images.

As we all know, it’s far too easy to become frustrated with an out-of-focus image, one that was made a split-second too late or early. As much fun as photography can be, it is by no means easy. We should remember that if we end up missing a photograph, even a historical one we were supposed to capture for a major publication, no one died on the operating table. In other words, the stakes are not as high as they are with a surgeon or a judge making critical decisions that will alter someone’s destiny.

Nevertheless, the right photograph taken at the right moment can change the path of a war by changing people’s perceptions of it. An example is Eddie Adams’ photograph of the Vietcong execution during the Vietnam War. Who knew that the act of focusing a lens and pressing a button could change the course of history?

There is one thing I deeply believe in when it comes to documentary photography: it’s not about you; it’s about the stories of the people you are photographing.

And yet I can honestly say that making a living taking pictures is one of the greatest guilty pleasures any human being can get away with.

If you go back to what my father told me when I was 16, photography is for everyone. You need not aim to be a photojournalist; you need not aim to change the world. All I recommend you do is have fun along the way. And take chances.

An aerial photograph of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina.

ISO 250 f/7.1 1/2000 180mm

While many of you may not yet know what your style or vision is (I certainly didn’t), the best way to discover them is to go out there, take chances, and see what images draw you in—see what errors lead to surprisingly successful images.

If you find that the image you are about to take doesn’t excite you, don’t take it. Doing so will almost guarantee that you will miss a much better photograph. After all, if you waste time making a mediocre image, you will likely run out of time to make the great image that may just be a few steps, or inches, away.

The photograph is a powerful thing. Regardless of the thousands of images and videos that are available to us out there, the still image holds a very important place in the media at large, no matter what anyone says.

As long as you follow your heart, as long as you are true to your subjects, and as long as you strive to make an image that you think captures something special or interesting either to yourself or to others, it is hard to fail.

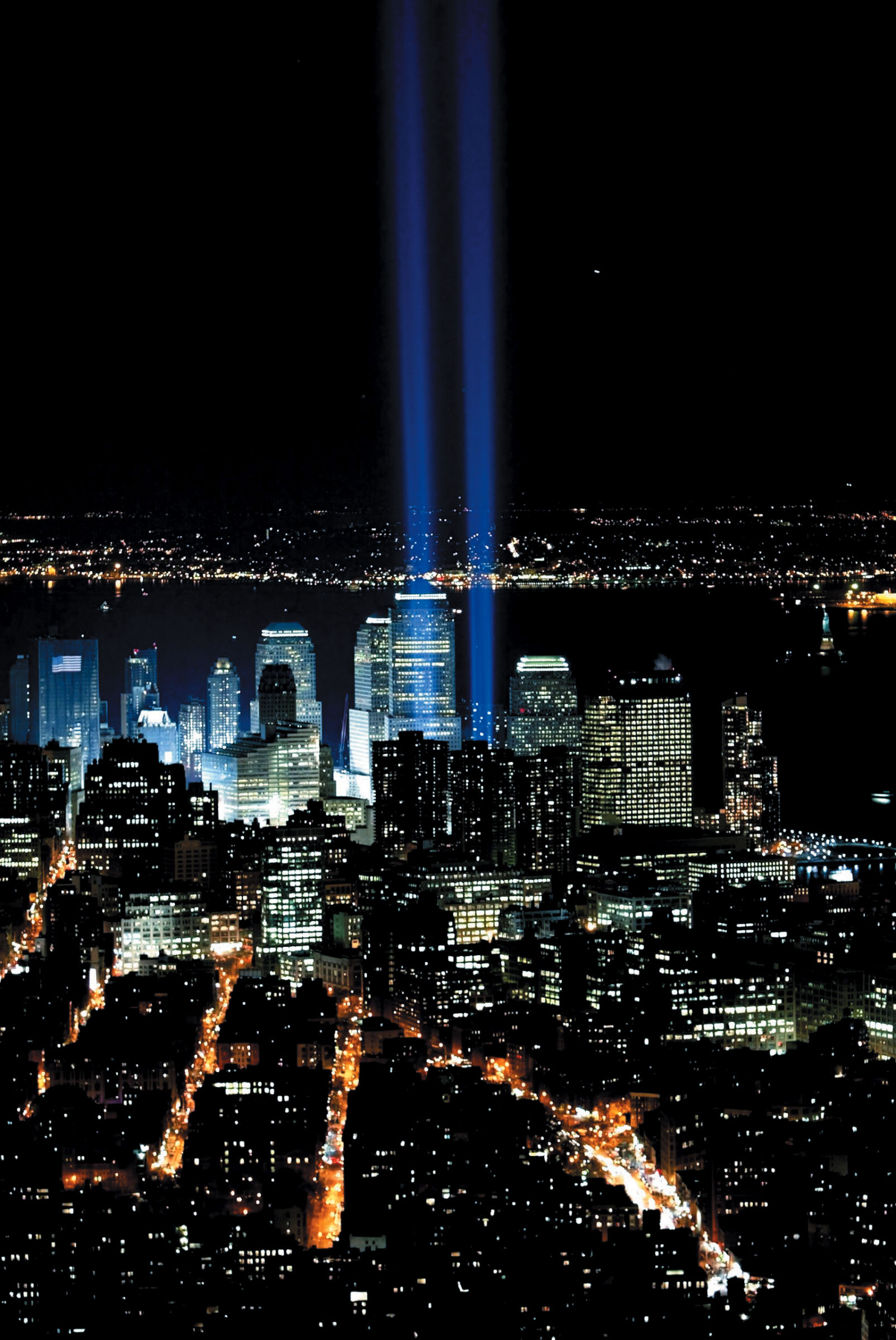

The twin beams of light rise near the World Trade Center site six months after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

ISO 200 f/2.8 1/15 70-200mm