9. Accessibility

Accessibility enhancements open up the iPhone to users with disabilities. iPhone OS features enable users to magnify (or “zoom”) displays, invert colors, and more. As a developer, accessibility enhancement centers on VoiceOver, a way that visually impaired users can “listen” to their GUI. VoiceOver converts an application’s visual presentation into an audio description.

Don’t confuse VoiceOver with Voice Control or the Siri Assistant. The former is a method for presenting an audio description of a user interface and is highly gesture based. The latter refers to Apple’s proprietary voice-recognition technology for hands-free interaction.

This chapter briefly overviews VoiceOver accessibility. You read about adding accessibility labels and hints to your applications and testing those features in the simulator and on the iOS device. Accessibility is available and can be tested on third generation or later devices, including all iPads, the iPhone 3GS and later, and the third-generation iPod touch and later.

Accessibility 101

Create accessibility by adding descriptive attributes to your user interface elements. This programming interface is defined by the informal UIAccessibility protocol and consists of a set of properties including labels, hints, and values. Together, they act to supply information to VoiceOver to present an audible presentation of your interface.

Either assign these properties in code or add them through Interface Builder (IB). Listing 9-1 shows how you could set a button’s accessibilityHint property. This property describes how this control reacts to a user action. In this example, the button’s hint updates when a user types a username into a related text field. The hint changes to match the context of the current UI. Instead of a general hint about placing a call, the updated version directly names its target.

Listing 9-1. Programmatically Updating Accessibility Information

- (BOOL)textField:(UITextField *)textField

shouldChangeCharactersInRange:(NSRange)range

replacementString:(NSString *)string

{

// Catch the change to the username field and update

// the accessibility hint to mirror that

NSString *username = textField.text;

if (username && username.length > 1)

callbutton.accessibilityHint = [NSString

stringWithFormat:@"Places a call to %@", username];

else

callbutton.accessibilityHint =

@"Places a call to the person named in the text field.";

return YES;

}

The UIAccessibility protocol includes the following properties:

• accessibilityTraits—A set of flags that describe a UI element. These flags specify how items behave or how they should be treated by the interpretive system. For example, these traits include state (for example, selected) and behavior (for buttons, for example).

• accessibilityLabel—A short phrase or word that describes the view’s role or the control’s action (for example, Pause or Delete). Labels can be localized.

• accessibilityHint—A short phrase that describes what user actions do with this element (for example, Navigates to the home page). Hints can also be localized.

• accessibilityFrame—A rectangle specifically for nonview elements, describing how the object should be represented onscreen. Views use their normal UIView frame property.

• accessibilityValue—The value associated with an object, such as a slider’s current level (for example, 75%) or a switch’s on/off setting (for example, ON).

Accessibility in Interface Builder

The Interface Builder (IB) Identity Inspector > Accessibility pane (see Figure 9-1) enables you to add accessibility details to UIKit elements in your interface. These fields and the text they contain play different roles in the accessibility picture. There’s a one-to-one correlation with the UIAccessibility protocol and the inspector elements presented in IB. As with direct code access, labels identify views; hints describe them. In addition to these fields, you’ll find a general accessibility Enabled check box and a number of Traits check boxes.

Figure 9-1. IB’s Identity Inspector lets you specify object accessibility information.

Enabling Accessibility

The Enabled check box controls whether a UIKit view works with VoiceOver. To declare an element’s accessibility support, assign the isAccessibilityElement property to YES, or check the Accessibility Enabled box in IB. (You can see this check box in Figure 9-1.) This Boolean property allows GUI elements to participate in the accessibility system. By default, all UIControl instances inherit a value of YES.

As a rule, enable accessibility unless the view is a container whose subviews need to be accessible. Enable only those items at the most direct level of interaction or presentation. Views that organize other views don’t play a meaningful role in the voice presentation. Exclude them.

Table view cells offer a good example of accessibility containers (that is, objects that contain other objects). The rules for table view cells are as follows:

• A table view cell without embedded controls should be accessible.

• A table view cell with embedded controls should not be. Its child controls should be.

Nonaccessible containers are responsible for reporting how many accessible children they contain and which child views those are. See Apple’s Accessibility Programming Guide for iPhone for further details about programming containers for accessibility. Custom container views need to declare and implement the UIAccessibilityContainer protocol.

Traits

Traits characterize UIKit item behaviors. VoiceOver uses these traits while describing interfaces. As Figure 9-1 shows, there are numerous possible traits you can assign to views. Select the traits that apply to the selected view, keeping in mind that you can always update these choices programmatically.

Traits help characterize the elements in your interface to the VoiceOver system. They specify how items behave and how they should be treated by VoiceOver. You set them via the accessibilityTraits property, by OR’ing together one or more flags. You can also set them in IB, as you saw in Figure 9-1. These traits vary in how they operate and how VoiceOver uses them.

At the most basic, default level, there’s the “no trait” flag:

• UIAccessibilityTraitNone—The element has no traits.

Then there are the flags that describe what the user element is. These include the following:

• UIAccessibilityTraitButton—The element is a button.

• UIAccessibilityTraitLink—The element is a hyperlink.

• UIAccessibilityTraitSearchField—The element is a search field.

• UIAccessibilityTraitImage—The element is a picture.

• UIAccessibilityTraitKeyboardKey—The element acts as a keyboard key.

• UIAccessibilityTraitStaticText—The element is unchanging text.

Apple’s accessibility documents request that you only check one of the following four mutually exclusive items at any time: Button, Link, Static Text, or Search Field. If a button works as a link as well, choose either the button trait or the link trait but not both. You choose which best characterizes how that button is used. At the same time, a button might show an image and play a sound when tapped, and you can freely add those traits.

There are a few basic state flags, which discuss the selection, adjustability, and interactive state of the object:

• UIAccessibilityTraitSelected—The element is currently selected, such as in a segmented control or the selected row in a table.

• UIAccessibilityTraitNotEnabled—The element is disabled from user interaction.

• UIAccessibilityTraitAdjustable—The element can be set to multiple values, as with a slider or picker. You specify how much each interaction adjusts the current value by implementing the accessibilityIncrement and accessibilityDecrement methods.

• UIAccessibilityTraitAllowsDirectInteraction—The user can touch and interact with the element.

If an element plays a sound when interacted with, there’s a flag for that as well:

• UIAccessibilityTraitPlaysSound—The element will play a sound when activated.

Finally, a handful of states caution and describe how the element behaves and interacts with the larger world:

• UIAccessibilityTraitUpdatesFrequently—The element changes often enough that you won’t want to overburden the user with its state changes, such as the readout of a stopwatch.

• UIAccessibilityTraitStartsMediaSession—The element begins a media session. Use this to limit VoiceOver interruptions when playing back or recording audio or video.

• UIAccessibilityTraitSummaryElement—The element provides summary information when the application starts, such as the current settings or state.

• UIAccessibilityTraitCausesPageTurn—The element should automatically turn the page once VoiceOver finishes reading its text.

As Figure 9-1 demonstrates, most of these traits (but not all) can be toggled off or on through the IB identity inspector pane. If you need finer-level control, set the flags in code.

Labels

You set an element’s label by assigning its accessibilityLabel property. A good label tells the user what an item is, often with a single word. Label an accessible GUI the same way you’d label a button with text. Edit, Delete, and Add all describe what objects do. They’re excellent button text and accessibility label text.

But accessibility isn’t just about buttons. Feedback, User Photo, and User Name might describe the contents and function of a text view, an image view, and a text label. If an object plays a visual role in your interface, it should play an auditory role in VoiceOver. Here are a few tips for designing your labels:

• Do not add the view type into the label. For example, don’t use “Delete button,” “Feedback text view,” or “User Name text field.” VoiceOver adds this information automatically, so “Delete button” in the identity pane becomes “Delete button button” in the actual VoiceOver playback.

• Capitalize the label but don’t add a period. VoiceOver uses your capitalization to properly inflect the label when it speaks. Adding a period typically causes VoiceOver to end the label with a downward tone, which does not blend well into the object-type that follows. “Delete. button” sounds wrong. “Delete button” does not.

• Aggregate information. When working with complex views that function as a single unit, build all the information in that view into a single descriptive label and attach it to that parent view. For example, in a table view cell with several subviews but without individual controls, you might aggregate all the text information into a single label that describes the entire cell.

• Label only at the lowest interaction level. When users need to interact with subviews, label at that level. Parent views, whose children are accessible, do not need labels.

• Localize. Localizing your accessibility strings opens them up to the widest audience of users.

Hints

Assign the accessibilityHint property to set an element’s hint. Hints tell users what to expect from interaction. In particular, they describe any nonobvious results. For example, consider an interface where tapping on a name—for example, John Smith—attempts to call that person by telephone. The name itself offers no information about the interaction outcome. So, offer a hint telling the user about it—for example, “Places a phone call to this person,” or even better, “Places a phone call to John Smith.” Here are tips for building better hints:

• Use sentence form. Start with a capital letter and end with a period. Do this even though each hint has a missing subject (for example, “Clears text in the form”). Here, the missing subject is “[This button].” Sentence format ensures that VoiceOver speaks the hint with proper inflection.

• Use verbs that describe what the element does, not what the user does. “[This text label] Places a phone call to this person.” provides the right context for the user. “[You will] Place a phone call to this person.” does not.

• Do not say the name or type of the GUI element. Avoid hints that refer to the UI item being manipulated. Skip the GUI name (its label, such as “Delete”) and type (its class, such as “button”). VoiceOver adds that information where needed, preventing any overly redundant playback, such as “Delete button [label] button [VoiceOver description] button [hint] removes item from screen.” Use “Removes item from screen.” instead.

• Avoid the action. Do not describe the action that the user takes. Do not say “Swiping places a phone call to this person” or “Tapping places a phone call to this person.” VoiceOver uses its own set of gestures to activate GUI elements. Never refer to gestures directly.

• Be verbose. “Place call” does not describe the outcome as well as “Place a call to this person,” or, even better, “Place a call to John Smith.” A short but thorough explanation better helps the user than one that is so terse that the user has to guess about details. Avoid hints that require the user to listen again before proceeding.

• Localize. As with labels, localizing your accessibility hints works with the widest user base.

Testing with the Simulator

The iOS simulator’s Accessibility Inspector is designed for testing accessible applications before deploying them to the iOS device. The simulator’s inspector simulates VoiceOver interaction with your application, providing immediate visual feedback via a floating pane (there is no actual voice produced) without having to use the VoiceOver gesture interface directly. Because you cannot replicate many VoiceOver gestures with the simulator (such as triple-swipes and sequential hold-then-tap gestures), the inspector focuses on describing interface items rather than responding to VoiceOver gestures.

Enable this feature by opening Settings > General > Accessibility. Switch the Accessibility Inspector to On. The inspector, shown in Figure 9-2, immediately appears. It lists the current settings for the currently selected accessible element.

Figure 9-2. The iPhone simulator’s Accessibility Inspector highlights the currently selected GUI feature, revealing its label, hint, and other accessibility properties.

Know how to enable and disable the inspector: The circled X in the top-left corner of the inspector controls that behavior. Click it once to shrink the inspector to a disabled single line. Click again to restore the inspector to active mode. For the most part, keep the inspector disabled until you actually need to inspect a GUI item. Figure 9-3 shows a button interface as described in the Accessibility Inspector.

Figure 9-3. The Accessibility Inspector reflects the values set either in IB or in code that describe the currently selected item.

Like VoiceOver, the inspector interferes with normal application gestures. It will slow down your work, so use it sparingly (normally when you are ready to test). You want to launch your application with the inspector disabled but available. Navigate to the screen you want to work with and then enable the inspector.

When you update accessibility hints in code, the inspector updates in real time to match those changes. Activating the inspector allows you to view the current hint as those changes happen, ensuring that the onscreen hints and labels reflect the up-to-date interface.

Broadcasting Updates

Your application should post notifications to let the VoiceOver accessibility system know about onscreen element changes outside of direct user interaction:

• When you add or remove a GUI element. The UIAccessibilityLayoutChangedNotification gives the VoiceOver accessibility system a heads up about those changes.

• Applications can post a UIAccessibilityPageScrolledNotification after completing a scroll action. The notification’s object should contain a description of the new scroll position (for example, “Page 5 of 17” or “Tab 2 of 4”).

• When the zoomed frame changes, send a UIAccessibilityZoomFocusChanged notification. Include a user dictionary with type, frame, and view parameters. These parameters specify the type of zoom that has taken place, the currently zoomed frame (in screen coordinates), and the view that contains the zoomed frame.

In addition to these change updates, you can broadcast general announcements through the accessibility VoiceOver system. The UIAccessibilityAnnouncement-Notification takes one parameter, a string, which contains an announcement. Use this to notify users when tiny GUI changes take place, or changes that only briefly appear on screen, or for changes that don’t affect the user interface directly.

Testing Accessibility on the iPhone

Testing on the iPhone is a critical part of accessibility development. The iPhone enables you to work with the actual VoiceOver utility rather than a window-based inspector. You hear what your users will hear and can test your GUI with your fingers and ears rather than with your eyes.

Like the simulator, the iPhone provides a way to enable and disable VoiceOver on-the-fly. Although you can enable VoiceOver in Settings and then test your application with VoiceOver running, you’ll find that it’s much easier to use a special toggle. The toggle lets you avoid the hassle of navigating out of Settings and over to your application using VoiceOver gestures. You can switch VoiceOver off, use normal iPhone interactions to get your application started, and then switch VoiceOver back on when you’re ready to test.

To enable that toggle, follow these steps:

1. Go to the Accessibility settings pane. Navigate to Settings > General > Accessibility.

2. Locate the Triple-click Home choice. The Triple-click Home button provides a user-settable shortcut for accessibility choices. Tap Triple-click Home to open the Home pane.

3. Choose Toggle VoiceOver. Select Toggle VoiceOver to set it as your triple-click action. Once selected (a check appears to its right), you can enable and disable VoiceOver by triple-clicking the physical Home button at the bottom of your iPhone. A spoken prompt confirms the current VoiceOver setting.

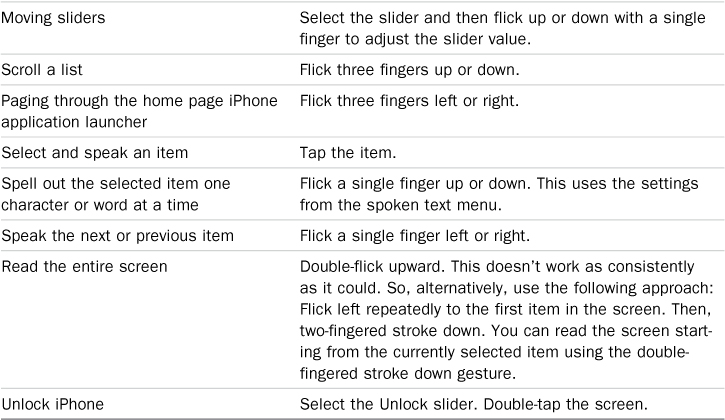

This VoiceOver toggle offers you the ability to skip many of the laborious details involved in navigating to your application using triple-fingered drags, and multistage button clicks. At the same time, you should be conversant with VoiceOver gestures and interactions. Table 9-1 summarizes the VoiceOver gestures that you need to know to test your application.

Table 9-1. Common VoiceOver Gestures for Applications

Take special note of ScreenCurtain, which enables you to blank your iPhone display, offering a true test of your application as an audio-based interface. Try the iPhone calculator application with ScreenCurtain enabled to gain a true sense of the challenge of using an iPhone application without sight.

Summary

When an iPhone application opens itself to Accessibility, it becomes an active participant in a wider ecosystem, with a larger potential user base. Here are a few thoughts to take with you:

• Including accessibility labels and hints create new audiences for your application, just as language localizations do. Adding these takes relatively little work to achieve and offers excellent payoffs to your users.

• Keep the role of labels and hints in mind as you prepare an auditory description of your application in IB.

• Don’t be afraid to change hints programmatically. Let your interface descriptions update as your interface does, to provide the best possible experience for your visually impaired users.

• iOS’s accessibility system is an evolving system. Keep on top of Apple’s documentation to find the latest updates and changes.

• Test with ScreenCurtain. A blank screen provides the best approximation of the VoiceOver user experience.