3. Fads, Fashions, and Bubbles

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, one by one.”

—Charles MacKay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

There is always a growth industry of tomorrow—whether it becomes the hot industry of today is another issue altogether. The hallowed halls of innovation are littered with the wreckage of innovative companies and even entire industries that failed to take off or took off but failed to stay aloft. Despite the promise of success reflected in the stock price or in the pitch to investors, some companies are just not able to hold on and maintain their value, let alone increase it.

The perception of value changes, and the perception of what will be valuable changes as well. Getting in early in companies that will be valuable—as any venture capitalist worth his salt can attest—can deliver astounding returns. However, some industries turn out to be mere fads reflecting the changing tastes and fashions of investors. The industry of tomorrow might seem destined to remain always in the future. Bets on these industries, or sometimes even entire countries, have led to some of the most spectacular bubbles in history.

Some bubbles seem so extreme that it boggles the mind. At the height of the Japanese real estate bubble, the Imperial Palace was estimated to be worth more than all of the land in the state of California, and Tokyo real estate sold for more than 350 times “choice property in Manhattan.”1 In 1989, the market value of stocks on the Tokyo Stock exchange was 44% of the total value for all equities in the world and was the largest stock market in the world based on market capitalization. The U.S. equity market in contrast accounted for roughly one-third of total market capitalization.2 Looking back on statistics like that, it seems incredible that the bursting of the Japanese stock and real estate bubble caught many by surprise. A 2012 report by Credit Suisse notes:

“Then the bubble burst. From 1990 to the start of 2009, Japan was the worst-performing stock market. ...Its weighting in the world index fell from 40% to 8%....”3

The bursting of the bubble was followed by an extended period of deflation and economic stagnation.4

Fads, fashions, and bubbles may have distinct causes, but they have the same result—asset prices that deviate from true value for significant periods of time. Whether it is an overhyped belief in one sector of the economy—such as technology, the Internet, or real estate that results in a bubble—or a rally based on a popular music video (fads and fashions), the end result is the same.

Is It Really a Bubble?

Many of the world’s most famous bubbles are viewed by some as not being bubbles at all. Moreover, timing the bursting of bubbles is difficult even when they are recognized as bubbles.

But what exactly is a bubble? Why are they so hard to predict? Why do some people claim that some of history’s most famous bubbles were not bubbles at all?5 Although it might seem accepted fact that academics have analyzed and understood the most famous bubbles in history, the fact is that disagreement exists among academics about whether some of the most famous bubbles of all time were bubbles at all.

The Dutch Tulip “bubble” took place in the mid-1630s. This bubble was further cemented in popular culture by its reference in the 2010 American movie, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. Many regard it as one of the most spectacular bubbles of all time, where the prices of tulip bulbs rose to extraordinary levels. According to Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, in 1636 one tulip was purchased for “12 acres of building-ground.”

In another case, a single tulip was supposedly exchanged for 6,700 Dutch guilders, a princely sum considering the average annual wage of that time to be a mere 150 guilders.6 At the height of the “bubble,” tulip bulb prices were incredibly expensive but, some academics argue still rational or justifiable based on economic fundamentals.7

Garber (1989) argues that the famous Dutch “Tulipmania” was, at best, a true bubble (in the popular sense of the word) only in the last month of speculation, and only for common (as opposed to rare) tulip bulbs.8 It follows that smart speculators—if they knew the true nature of the bubble—could have made a killing by riding it out to the very end—easier said than done, even for a genius.

Speaking of genius, Isaac Newton faced exactly this problem in the South Sea bubble which burst in 1720. He initially realized it was a bubble and sold his stock at 7,000 pounds, a 100% profit. However, he was lured back into the market at the height of the bubble and lost 20,000 pounds. Perhaps he fell victim to the “greater fool” theory. This led to his famous and memorable quote:

“I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”9

In more modern times, some academics and market practitioners have questioned whether the NASDAQ Internet bubble was actually a bubble at all10 because, among other reasons, like options,

“...a firm’s fundamental value increases with uncertainty about average future profitability, and this uncertainty was unusually high in the late 1990s.”11

Even with the benefits of hindsight—and in the case of the NASDAQ “bubble”—extremely detailed data, debates occur over which seemingly apparent bubbles are actually real bubbles. This difference of opinion is important not only at an academic level, but also for traders and policymakers alike. If we can’t agree on what a bubble is with the benefit of hindsight, how can a trader protect himself and profit from the bubbles of the future? Also, how—regardless of whether they are referred to as “bubbles”—will traders avoid being on the wrong side when the bubble suddenly inflates or bursts? Similarly, knowing whether sharply higher asset prices are a bubble or the result of economic fundamentals is also important for policymakers if they are to make informed policy decisions.

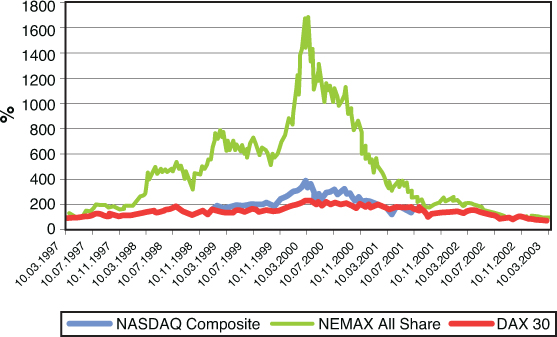

Although much attention has been directed in the popular press and academic literature to the NASDAQ tech/internet (or Dotcom) bubble, the price behavior of the Neuer Markt has received far less attention. This is unfortunate because the Neuer Markt rose far higher and faster and fell far more than the NASDAQ, as shown in Figure 3-1 (reproduced from a 2010 Deutsche Bundesbank study of the Neuer Markt by Dr. Ulf von Kalckreuth and Dr. Leonid Silbermann). The presumed “tech bubble” on the NASDAQ pales in comparison with the tech bubble on the Neuer Markt. Kalckreuth and Silbermann [2010] state:

“In March 1997, the Neuer Markt in Germany opened. Six years later, in June 2003, it closed forever. In the interim period lay the spectacular rise and fall of the first and most important European market for hi-tech stocks. Given investors’ frenzy, the Neuer Markt was a special kind of natural experiment: For a limited time, financing constraints were virtually non-existent....

“Even compared to NASDAQ, the evolution of the Neuer Markt looks extreme. On 10 March 2000, the NEMAX All Share reached its ultimate high of 8,583 points, corresponding to an increase of 1,682% since the opening three years earlier. The market capitalisation of the 229 companies listed in the NEMAX All Share index on that date was €243 billion. What then followed was an equally spectacular decline, leading to the closing down of the Neuer Markt on 5 June 2003....”12

(Reprinted with permission of Drs. Ulf von Kalckreuth and Leonid Silbermann.)

Figure 3-1. The behavior of the DAX, NASDAQ, and NEMAX stock indices during the 1997 through 2003 period. This chart is reproduced from a 2010 Deutsche Bundesbank, Discussion Paper, “Bubbles and Incentives: A Post-Mortem of the Neuer Markt in Germany,” by Drs. Ulf von Kalckreuth and Leonid Silbermann.

Interestingly, both the Neuer Markt and NASDAQ peaked on March 10, 2000. Within two years of reaching its peak, the Neuer Markt declined by 96%.13 This makes the “crash” in the NASDAQ look small in comparison.

Perhaps surprisingly, econometric evidence of the existence of “bubbles” is mixed at best. Many studies report no evidence of bubbles in market prices.14

Part of the reason why the existence of bubbles remains controversial in academia is that it implies that markets are not efficient or “smart.” That is less of a problem than its implication for market makers. If assets are substantially mispriced, those making a market in them should eventually suffer large losses. One famous trader has argued that options on tech stocks were correctly priced during the supposed tech bubble because the option price allowed for the underlying stock price to more than double or crash. The fact that many of the tech stocks on which options were written subsequently crashed does not mean that the options were mispriced as the option price allowed for this possibility. Moreover, most of the firms making markets in options during the tech bubble period are still in business—which they wouldn’t be if options were systematically mispriced.

Can You Profit from “Bubbles”?

There are those who have, to use Newton’s words, attempted to “calculate...the madness of people.” Some evidence exists (Brunnermeier and Nagel [2004]) that hedge funds were able to ride the wave of the technology bubble and reduce their exposure before the crash. This is important because it has implications for the validity of the efficient market hypothesis—namely that rational investors do not stabilize prices; they might, in fact, ride a bubble and get out just before it bursts. The paper notes:

“Overall, our evidence casts doubt on the presumption underlying the efficient markets hypothesis that it is always optimal for rational speculators to attack a bubble.”15

It also has implications for trading strategy. The paper concludes:

“...riding a price bubble for a while can be the optimal strategy for rational investors...”16

The view that sophisticated investors were aware that the late ’90s tech bubble was a bubble (before it burst) was reinforced by Bracha and Weber [2012], who noted:

“...a Barron’s survey of professional money managers in 1999 revealed that 72 percent of the respondents believed the stock market to be in a speculative bubble.”17

Seventy-two percent were able to identify that the market was in a bubble, but it is extremely hard to predict when a bubble will burst.18 If crashes happen even when the fundamentals are strong, predicting exactly when a bubble will burst is that much harder. George Soros’ Quantum fund shorted the NASDAQ too soon and lost a boatload, according to Ziemba and Ziemba [2008]:

“Quantum lost about $5 billion of its $13 billion size shorting the Nasdaq too soon. Had they started shorting about two months later in April 2000, they could possibly have made ten times this amount.”19

This example underscores two realities facing those who short bubbles:

• Shorting a bubble too soon can cost you a fortune even though you are right about the market being in a speculative bubble.

• Even the greatest hedge fund managers of all time have difficulty timing when exactly to begin shorting bubbles.

Legendary hedge fund manager, Julian Robertson, earned an impressive 31.7 percent return after fees for his clients in Tiger Management over 18 years. Yet, he felt compelled to close Tiger Management—at one time the largest hedge fund in the world—during the tech bubble, in part, because the markets didn’t make sense to him.

This sentiment is captured in Mr. Robertson’s letter to investors posted on the CNNMoney website.

“...There is a lot of talk now about the New Economy (meaning Internet, technology and telecom)... ‘Avoid the Old Economy and invest in the New and forget about price,’ proclaim the pundits. And in truth, that has been the way to invest over the last eighteen months.”

“As you have heard me say on many occasions, the key to Tiger’s success over the years has been a steady commitment to buying the best stocks and shorting the worst. In a rational environment, this strategy functions well. But in an irrational market, where earnings and price considerations take a back seat to mouse clicks and momentum, such logic...does not count for much.”

“The current technology, Internet and telecom craze, fueled by the performance desires of investors, money managers and even financial buyers, is unwittingly creating a Ponzi pyramid destined for collapse. The tragedy is, however, that the only way to generate short-term performance in the current environment is to buy these stocks. That makes the process self-perpetuating until the pyramid eventually collapses under its own excess.”

“I have great faith though that, ‘this, too, will pass.’ ...The difficulty is predicting when this change will occur and in this regard I have no advantage....”20

In yet another sign of the difficulty of timing the bursting of a bubble, Julian Robertson announced the closure of Tiger Management 20 days after the NASDAQ stock index peaked.

To be sure, nonsensical markets were not the only reason for Mr. Robertson’s decision. In a conversation with one of the authors, Mr. Robertson indicated that age was also a factor in his decision to close Tiger Management—Robertson was 70 at the time—as was his desire to devote more time to his passion for philanthropy.

This brings to mind the famous quote by Keynes, “Markets can remain irrational a lot longer than you and I can remain solvent.”21 That said, extreme rewards are available to those who correctly short a bubble. For instance, as noted earlier, Ziemba and Ziemba [2008] estimated that George Soros’ Quantum Fund lost $5 billion from shorting the NASDAQ while the bubble was still inflating, but they could have made up to $50 billion had they started shorting the NASDAQ two months later.22 Although the loss of $5 billion is gigantic, it was a 10-to-1 bet (if the Ziemba and Ziemba [2008] analysis is correct).

Even policymakers with great power and access to much information are at a loss to predict when asset prices are overvalued. Alan Greenspan famously underscored this point when he said during an after-dinner speech at the American Enterprise Institute on Thursday, December 5, 1996:

“But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?”23

Although Greenspan phrased his comment as a question, the market interpreted it as a statement of fact. Stocks around the world immediately sold off due to fears of an overbought market. This famous “irrational exuberance” quote caused a 3% drop in stock markets in Tokyo and Hong Kong, a 4% drop in both Frankfurt and London, and a later 2% drop at the opening of the U.S. stock market. Mr. Greenspan underscored the difficulty of really knowing when prices are overvalued—while the very fact he expressed worry likely led some market participants to believe assets were overvalued—thus leading to a sell off.24

Suppose for a moment that you agreed with Greenspan’s “irrational exuberance” comment and shorted NASDAQ and S&P 500 stocks the next day. When would the trades become profitable and how long would they remain profitable?

On Thursday, December 5, 1996, the DJIA closed at 6,437.10. The NASDAQ Composite closed at 1,300.12. If you had shorted a portfolio mirroring the DJIA at the close on December 5, 1996 and held it due to fears of irrational exuberance, it would have been profitable for at most two weeks. A trader short the NASDAQ Composite stock index at the close on December 5, 1996 would have been profitable until early 1997 and then unprofitable until mid-March 1997 and then unprofitable after May 2, 1997 as the NASDAQ rose. The NASDAQ Composite rose to a high of 5,132.52 on March 10, 2000. The NASDAQ fell thereafter, but a short position entered at the close on December 5, 1996 would not have been profitable again until July 22, 2002. And even that would have been profitable only until October 29, 2002.

The market might have been subject to “irrational exuberance.” However, except for these brief periods of profitability, going against the trend, however irrational it was, would have cost you dearly. How much pain would you have been willing to bear before calling it quits and covering your short position? Bearing a substantial amount of unnecessary financial pain by letting your losses grow might or might not make you a better person. Unquestionably, letting your losses grow makes you a poorer person.

Is the Market Smart?

Alan Greenspan’s irrational exuberance remark and the market’s reaction to them highlights a phenomenon discussed in detail by legendary trader George Soros; namely, the principle of reflexivity. Soros argues that financial markets are not efficient, which has stunning implications for the stability of prices and the financial system as a whole. In a speech on June 10, 2010 at the Institute for International Finance (IIF) Spring Membership Meeting in Vienna, he argued:

“I have developed an alternative theory about financial markets which asserts that financial markets do not necessarily tend toward equilibrium; they can just as easily produce asset bubbles. Nor are markets capable of correcting their own excesses....

“...First, financial markets, far from accurately reflecting all the available knowledge, always provide a distorted view of reality. This is the principle of fallibility. The degree of distortion may vary from time to time. Sometimes it’s quite insignificant, at other times it is quite pronounced....

“...Second, financial markets do not play a purely passive role; they can also affect the so-called fundamentals they are supposed to reflect....”25 (emphasis added by authors)

He argues, in contrast to conventional economic theory, not only is the market not always efficient, but that it is, in fact, oftentimes wrong. That is because the market is made up of many individual participants who, being human, are inherently fallible. This fact is highly relevant to investors because it underscores just how uncertain the markets can be about what is or is not a quality asset—and how quickly that can change. If Soros is right—and as one of the most successful hedge fund managers of all time, he has quite a bit of credibility—then market participants must be vigilant and careful when trading and even more so when choosing “safe” assets. Moreover, this theory also suggests that, because markets just as easily produce bubbles, periodic crises are more likely than financial theory suggests.

Although some people like to think of the markets as run by pure rationality, in reality, emotions such as fear and greed play a large role. The sudden shift in risk preferences among market participants lowers the price of risky assets relative to safe assets.

Perhaps ironically, due to his fame and clout in the markets, George Soros has created his own reflexive situations in the past. The Wall Street Journal tells the story of an emerging market bond trader at Kidder Peabody who heard a rumor:

“...that Soros funds were buying Peru’s currency. He ordered his traders to buy Peruvian bonds ... Peru’s currency rallied, and Kidder’s bonds jumped about 500% in six months.”26

Does that mean that Soros alone caused the rise in the currency? No. But his fame and clout attracted other traders to the trade, pushing the price higher and faster than it might otherwise have gone. Situations like this arise in the market on a regular basis. As discussed later in the book, David Einhorn’s shorting of Green Mountain Coffee Roasters and Carson Block’s shorting of Sinoforest are both examples of how the actions of some traders can also be a trading catalyst. A similar story can often be told about the market’s response to news of changes in security positions by Warren Buffet. Even so, Soros’ belief that markets produce bubbles as easily as they tend toward equilibrium is not universally accepted.

Market Efficiency

All of this calls into question the age-old question: Are markets efficient? Do prices fully and correctly reflect available information?27 The theory of market efficiency owes its origin in part to observations that changes in commodity and security prices appeared to fluctuate randomly. This led to the development of the random walk hypothesis—the notion that changes in financial market prices fluctuate randomly in an efficient market. This turned out to be more restrictive than necessary but the term remains popular among the public. One of the implications of market efficiency is that it is impossible, in the long term, to consistently beat the stock market.

However, some traders have done exactly that:

“Four hundred seventy-three million to one. Those are the odds against George Soros compiling the investment record he did as the manager of the Quantum Fund from 1968 through 1993. His investing record is the most unimpeachable refutation of the random walk hypothesis ever!”28

The overall performance of traders like George Soros and Paul Tudor Jones II or investors like Julian Robertson and Warren Buffet does not lie. Consistently beating the market is difficult, but possible. However, merely stating that some traders have consistently beaten the market does not mean markets are not efficient.

Our position is that markets are not always efficient. However, when evaluating your trading options, you should assume the market has incorporated all relevant information. Start with the assumption that the market price accurately reflects the value, and then find a way to go from there. The burden of proof is on you, the trader, to prove why the market price is off and develop a strategy for how to profit off of it.

Taken to an extreme—that markets are always efficient—means that you should never trade because it’s impossible to make money (save by chance). Taken to the extreme that markets are always and extremely inefficient, it becomes very hard to evaluate the true price of anything and to develop a credible trading thesis.

Irrational Speculation and the Limits of Rational Analysis

Speaking of risky, irrational, and speculative plays, one of the most memorable rallies in recent memory was the huge surge in the stock price of the Korean company DI, a semiconductor firm.

But what triggered the rally? Was it a large order from Samsung? The use of its chips in the newest iPhone? A record-breaking earnings report? A groundbreaking new technology? None of the above. So what could it be?

What about a catchy song about a man who dances like a horse?

That’s right—popular song and Internet phenomenon “Gangnam Style” caused the spike in DI shares. Since the July 2012 release of the song, shares of DI surged “eightfold.”29 How is this possible?

South Korean rapper PSY, the man behind “Gangnam Style,” is the son of DI’s chairman. One could be forgiven for pressing the question: “Still, how is this surge possible?”

That’s because the company doesn’t even have a stake in “Gangnam Style,” and in fact, had many problems. It turns out DI had lost money for the previous four quarters. The company that does have a stake in “Gangnam style,” YG Entertainment—PSY’s management company—merely saw its value rise 30%.30

So, just stepping back a bit, let’s put this situation in perspective. The company that is positioned to make money off of “Gangnam Style” saw its stock price increase by 30% but a company with a chairman related to PSY by blood—and which has lost money for four consecutive quarters—saw an eightfold increase?

It doesn’t make a lot of sense.

This occurrence is not unprecedented in Korea. The Economist points out the Korean phenomenon of the “theme stock.”31 The shares of one company rise due to a newfound association to a famous person or an important company. For example, the article noted that shares of a company called Bolak surged to 9,000 won from 2,000 won when the owner’s daughter married into the family that controls LG.32

But similar events aren’t just tied to real—if possibly overhyped—beliefs about the future prospects and connections a marriage could bring. The Economist article also noted that a similar, irrational rally occurred when a picture appeared of presidential political hopeful Moon Jae-in sitting next to a man who appeared to be CEO of Daehyun. The stock rose 350%. In fact, the man was not CEO of Daehyun, and the entire case might have been a pump-and-dump fraud.33 The case illustrates the propensity of shares to rapidly rise based on connections that might be weak at best. Would the stock have been 350% more valuable even if the picture were real?

Upon first glance, these examples appear to be irrational. In fact, from a fundamental perspective, they are. However, it is perfectly rational for trend followers to try to ride the wave, regardless of whether they believe it is grounded in reality. If you have good reason to suspect that a stock will rise several hundred percent—regardless of whether it should—buying may make sense. This is logical on an individual level, and it helps precipitate bubbles and encourages irrational valuations.

These types of relationships are not limited to the Korean market. Fads and fashions in finance occur across countries. Shiller [2000] argues:

“Often, speculative bubbles appear to be common to investments of a certain ‘style,’ ...the stock market bubble that peaked in ... 2000 was strongest in tech stocks or Nasdaq stocks.”34

Anecdotal evidence suggests fads in various periods such as radio stocks in the 1920s, conglomerates in the 1960s, dotcom companies in the 1990s, or biotech companies more recently.

It does not suggest that all the examples are irrational. Connections are crucial, especially in Asian countries, and marrying into a rich family or knowing famous politicians can be a boon for a business in any country. It is certain, however, that the stocks in the previous examples exhibited highly unusual behavior seemingly not justified by fundamentals.

But what about stocks with behavior justified by the fundamentals? What about conservative choices with companies unlikely to get caught up in bubbles? If trading off of bubbles is a strategy to make money, can investing in companies unlikely to be subject to extraordinary growth be a winning strategy as well? Warren Buffett has made a career by investing in non-glamorous conservative companies. In an investor letter, he wrote:

“What counts ... is intrinsic value.... With perfect foresight, this number can be calculated by taking all future cash flows of a business—in and out—and discounting them at prevailing interest rates....”35

This approach puts all companies on an equal footing for investment comparison purposes holding risk constant. Sounds rational right? Yet, it is not that simple, especially during short-, or even medium-term periods. Buffett famously once said:

“Only buy something that you’d be perfectly happy to hold if the market shut down for 10 years.”

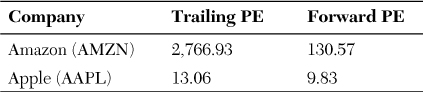

His trading advice using conventional tools of analysis such as discounted cash flows has served him well in the long run, but it is much less relevant for shorter time periods. For instance, price earnings ratios are a widely used valuation metric. Sometimes, P/E ratios are so incredibly high that their utility as a valuation metric is doubtful. An article on Forbes.com summed this up nicely by comparing the valuation of Apple versus Amazon on November 3, 2012.36

As noted in the article, Apple fell on higher earnings while Amazon rose on a reported loss. Those facts alone are enough to give one pause, but this next quote—comparing trailing PE ratios—boggles the mind:

“Put another way, if it takes Apple 13 years to pay back your initial investment, it will take Amazon nearly three millennia.”37

The point is, using P/E ratios, especially a trailing P/E ratio, makes Amazon look extraordinarily overvalued. However, markets are forward looking so the forward P/E ratio should be used in valuation, but even using the forward P/E ratio causes Amazon to look potentially overvalued.

However, if you take the period from November 2, 2012 to December 3, 2012, you see a 7.83% rise in AMZN with a corresponding –1.73% return for AAPL. What does this prove? Absolutely nothing—except that the market delivers great returns to assets seen by any number of metrics as overvalued. On paper, Amazon looked expensive in November, but it still returned 7% in one month. Shorting the stock would have produced losses and buying what appeared to be expensive shares would have been a good idea. There were arguments that AAPL, too, was overvalued. Purely looking at Apple’s fundamentals painted a much rosier picture than Amazon’s. The point is that assets that appear overvalued might deliver great returns, and might in fact be undervalued. The deeper point is that in the short and medium term, the “intrinsic value” of a stock might have no correlation to performance.

Irrational Pricing

Sometimes seeming instances of irrational pricing might be more apparent than real. Consider the March 2000 sale by 3Com of part of its stake in Palm. 3Com also announced it would get rid of the rest of its holdings by giving 3Com shareholders 1.484 shares of Palm for each share of 3Com they owned.38 This suggests that the minimum value of 3COM is the value of the Palm shares to be received. Yet, as University of California at Berkeley Professor Hal R. Varian, pointed out in the New York Times:

“...Palm shares were worth $95.06 a share while 3Com shares fell to $81.81. The market was valuing the non-Palm part of 3Com’s business at minus $63.”39

This appears to be a stunning pricing anomaly. Although the price of 3Com shares fell to only $81.81, in some ways, they actually fell to less than zero. When you factor in the implied value of 3Com based on the share disbursement offer, either 3Com was less than worthless, or the market mispriced it.

Many economists like to think of financial markets as being rational, yet effectively pricing 3Com shares at a value less than zero seems extremely irrational.

Professor Varian advanced several possible reasons for this intense overvaluation. The reason he gave as most likely for the discrepancy on the first day of trading, trader ignorance of the relationship, also seems almost counterintuitive.40

But it can’t be just that everyone was asleep at the wheel. This discrepancy was clearly noticed, as at one point, 147.6% of the shares outstanding were borrowed to short.41 Yet despite the clear apparent arbitrage profit opportunity, the price difference continued for two months until the Internal Revenue Service approved the spin-off as a tax-free transaction, as noted by McKinsey and Co:

“...At that point, ...the price discrepancy disappeared. This correction suggests that at least part of the mispricing was caused by the risk that the spin-off wouldn’t occur.”42

Professor Varian suggests that the persistence of the discrepancy might be explained by short-selling constraints and short-selling risk.43 Indeed, the McKinsey study notes that it was difficult to borrow Palm shares to short because 3Com held 95% of them.44

A combination of factors—the extreme difficulty of selling short due to the small number of shares available at the time, uncertainty over the interest rate to be charged on open short positions, uncertainty about whether the spin-off would occur, and over-enthusiasm on the part of less sophisticated investors—all played a part in creating a seeming arbitrage profit opportunity.

Shiller [2003] makes a similar argument that shorting stocks that appear overvalued is often both difficult and expensive and cites the 3Com—Palm case as an example. He states:

“... [There was] strong incentive...to short Palm and buy 3Com. But, the interest cost of borrowing Palm shares reached 35 percent by July 2000, putting a damper on...exploiting the mispricing....45

This example supports the idea that in the long run, markets might be efficient, but in the short run, they are not necessarily so. It also suggests that many seeming arbitrage profit opportunities are more apparent than real because it is often difficult to exploit mispricings. Simply stated, many seeming profit opportunities are exactly that—seeming—and persist because they can’t be easily exploited.

Trading Lessons

Fads and fashions in trading and investing have always been a characteristic of financial markets. Sometimes investor excitement over rapidly rising asset prices results in apparent speculative bubbles. Bubbles are not confined to the distant past as the sudden rise and rapid fall of the Neuer Markt from 1997 to 2003 demonstrates.

Some of the world’s most savvy investors have recognized and profited from bubbles, yet even they have been caught by the bubbles’ unpredictable burst. Legendary hedge fund managers Julian Robertson and George Soros provide hard evidence that even the world’s best investors and traders can be caught flat-footed by bubbles. Finally, some apparent “bubbles,” such as the unbelievable valuation of Palm, are simply mispricings that cannot be easily exploited.

Endnotes

1. Epstein, E.J., “What Was Lost (and Found) in Japan’s Lost Decade.” Vanity Fair. February 17, 2009. http://www.vanityfair.com/online/daily/2009/02/what-was-lost-and-found-in-japans-lost-decade.

2. Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2012. https://www.credit-suisse.com/investment_banking/doc/cs_global_investment_returns_yearbook.pdf.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. The popular definition of a bubble as a market whose assets trade at greatly inflated prices relative to their fundamental economic value differs from the view of many economists who define a bubble more narrowly. LeRoy [2004] argues: “Many contemporary writers are more sympathetic to the idea of irrationality...Irrationality is identified...with the existence of agents who trade for reasons that are not modeled (‘noise traders’). Along these lines, bubbles are presumably defined as the difference between asset prices as they are and asset prices as they would be in the absence of noise traders.” LeRoy, S.F., “Rational Exuberance,” Journal of Economic Literature, XLII, (September 2004) pp. 783–804.

6. Gross, D. “Bulb Bubble Trouble.” July 16, 2004. http://www.slate.com/articles/business/moneybox/2004/07/bulb_bubble_trouble.html.

7. Thompson [2007] argues: “[T]ulip contract prices before, during, and after the “tulipmania” appear to provide a remarkable illustration of efficient capital market prices, where options prices approximated the expected costs to the informed suppliers...” Thompson, E., “The Tulipmania: Fact or Artifact?,” Public Choice, 130, No. ½ (January 2007), pp. 99–114.

8. Garber, P., “Tulipmania,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 97, No. 3, 1989, pp. 535–557.

9. This statement has been attributed to Newton, although its provenance is in dispute. Wikiquote indicates a similar statement attributed to Isaac Newton in a Church of England Quarterly Review in 1850. http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Isaac_Newton.

10. Pastor, L., and P. Veronesi. “Was there a Nasdaq bubble in the late 1990s?” Journal of Financial Economics. Vol. 81(1), pages 61–100, July, 2006.

11. Ibid.

12. Kalckreuth, U. and L. Silbermann, “Bubbles and Incentives: A Post-Mortem of the Neuer Markt in Germany,” Deutsche Bundesbank, Discussion Paper, Series 1: Economic Studies No. 15/2010, 2010.

13. Carney, B.M., “Teutonic Tailspin: German Market’s Rise and Fall,” Wall Street Journal, October 1, 2002.

14. See Gurkaynak [2008] for a review of the literature. Gurkaynak, R.S., “Econometric Tests of Asset Price Bubbles: Taking Stock,” Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 22, 2008, pp. 166–186.

15. Brunnermeier, M. and S. Nagel, “Hedge Funds and Technology Bubble,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 59 (5), 2004, pp. 2013–2040.

16. Ibid.

17. Bracha, A., and E.U. Weber, “A Psychological Perspective of Financial Panic,” Public Policy Discussion Papers, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, September 2012. http://www.bostonfed.org/economic/ppdp/index.htm.

18. Not all bubbles seem to be as predictable. Radelet and Sachs [(2000]) noted that the East Asian Crisis was “...the least anticipated crisis in years.” Radelet, S. and J. Sachs. 2000. “Lessons from the Asian Financial Crisis.” In B.N. Gosh, ed., Global Financial Crises and Reforms: Cases and Caveats (London, U.K.: Routledge Press), pp. 295–315.

19. Ziemba, Rachel E. S. and William T. Ziemba, Scenarios for Risk Management and Global Investment Strategies. New York: Wiley, 2008, pp. 81–82.

20. Karchner, J., “Tiger Management Closes,” CNNMoney, March 30, 2000. http://money.cnn.com/2000/03/30/mutualfunds/q_funds_tiger/

http://money.cnn.com/2000/03/30/mutualfunds/q_funds_tiger/sidebar.htm. The extended quote is reprinted with permission of Julian Robertson.

21. Quote attributed to Keynes by A.G. Shilling, Forbes (1993) v. 151, iss. 4, pg. 236.

22. Ziemba, R.E.S. and W.T. Ziemba, Scenarios for Risk Management and Global Investment Strategies. New York: Wiley, 2008, pp. 81–82.

23. “Remarks by Chairman Alan Greenspan,” at the Annual Dinner and Francis Boyer Lecture of the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C., December 5, 1996. http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/1996/19961205.htm.

24. Interestingly, while Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan expressed concern over the existence of a possible stock market bubble, the Federal Reserve chose not to take any steps, such as making it more difficult for investors to buy stock on margin, that might have made it more difficult for the bubble to continue to inflate.

25. http://www.georgesoros.com/interviewsspeeches/entry/iif_spring_membership_meeting_address_june_10_20101/. Extended quote reprinted with permission of George Soros and the Institute for International Finance.

26. “How the Soros Funds Lost the Game of Chicken Against Tech Stocks.” Wall Street Journal. May 22, 2000.

27. “A market in which prices always ‘fully reflect’ available information is called ‘efficient.’” Fama, E.F., “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work,” Journal of Finance, XXV, No 2 (May 1970), pp. 383–417.

28. Jones II, P.T., Foreword. In Soros, G., The Alchemy of Finance: Reading the Mind of the Market, New York: Wiley 1994.

29. Nakashima, Ryan. “Gangnam Style Sensation PSY Will Rake In $7.9 Million This Year.” Business Insider. Dec 5, 2012. http://www.businessinsider.com/gangnum-style-sensation-psy-will-rake-in-79-million-this-year-2012-12.

30. Ibid.

31. “Bubbly Pop.” The Economist. October 2, 2012. http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2012/10/investing-gangnam-style.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Shiller, R.J., “From Efficient Markets Theory to Behavioral Finance,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Winter 2003), pp. 83–104.

35. Buffett, Warren, Berkshire Hathaway 1989 Letter to Shareholders. http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1989.html.

36. Elmer-DeWitt, P., “Amazon’s price-to-earnings ratio is now 2,767. Apple’s is 13.” http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2012/11/03/amazons-price-to-earnings-ratio-is-now-2767-apples-is-13/.

37. Ibid.

38. Company News, “3COM, A Computer Networker, Sets Spinoff Terms.” New York Times. July 15, 2000. http://www.nytimes.com/2000/07/15/business/company-news-3com-a-computer-networker-sets-spinoff-terms.html.

39. Varian, H.R., “Five Years After Nasdaq Hit Its Peak, Some Lessons Learned,” New York Times, March 10, 2005. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/10/business/10scene.html?ref=halrvarian

40. Ibid.

41. http://www.chicagobooth.edu/capideas/win02/market.html.

42. McKinsey Quarterly, “Do Fundamentals or Emotions Drive the Stock Market?,” April 13, 2005. http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/3839631?f=singlepage.

43. Varian, H.R., “Five Years After Nasdaq Hit Its Peak, Some Lessons Learned,” New York Times, March 10, 2005. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/10/business/10scene.html?ref=halrvarian.

44. McKinsey Quarterly, “Do Fundamentals or Emotions Drive the Stock Market?,” April 13, 2005. http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/3839631?f=singlepage.

45. Shiller, R.J., “From Efficient Markets Theory to Behavioral Finance,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Winter 2003), pp. 83–104.