5. Rumor Has It

“Buy the rumor and sell the news”

—Trading adage

At approximately 11:45 a.m. on Monday, January 7, 2013, the Australian Financial Review website reported that ANZ bank had cancelled a $1.2 billion loan to Whitehaven Coal—for environmental reasons. The news triggered a sharp selloff in Whitehaven Coal stock. The slide worsened as other news outlets picked up the story. Before trading in the stock was suspended less than an hour later at 12:41 p.m., Whitehaven’s market capitalization had fallen almost AUD$300 million, or about 9 percent. The “news” was soon discovered to be a hoax perpetrated by an anti-coal mining activist, and the price of Whitehaven Coal shares quickly recovered when trading in the stock reopened at 1:30 p.m.1 None of the trades that occurred during the 11:45 to 12:41 period were cancelled by the exchange. Moreover, the hoax was not a rare event as The Australian newspaper noted:

“The hoax—[was] the third to strike a stock market listed company in the past six months....”2

This chapter examines the impact of rumors and the position announcements of high-profile traders and investors on market prices. Both can be powerful sources of market shocks. Understanding when to act on a rumor—and when to ignore it—is a difficult but crucial task as the previous example shows.

Rumors

What is more important when making decisions: rumor or fact? In polite society, the answer is almost always fact. In financial markets, the answer is more often rumor. The difference lies in the competition to incorporate available information into market prices quickly. The inherent risk present in financial markets means traders must act quickly and decisively to avoid or minimize sudden losses. Likewise, the opportunity for sudden gains can be fleeting so traders must act swiftly to seize them when they arise. In both cases, traders make decisions to enter or exit security positions based often on very limited information. Getting the complete facts might take too long; hence, the power of rumors.

Common sense suggests that the source of rumors should be an important factor in determining their influence, but the source of rumors is often unknown. In fact, rumors don’t even have to be credible to exert an influence on market prices. After prices start moving, that action conveys information to other market participants, which then increases the power and the credibility of the rumor.

The information in rumors might be fully valid, demonstrably false, or somewhere in between. Rumors might arise inadvertently or be intentionally spread. Although knowingly spreading false market rumors is a crime in many countries, the incentive to do so is great, and apprehending and convicting those spreading rumors is difficult.

United Airlines Takes a Nosedive

Shares in UAL, the parent company of United Airlines, witnessed a gigantic 76% drop on September 8, 2008 when a six-year-old story—reporting on the then-current 2002 bankruptcy of United airlines—riled the markets and led many to believe UAL had declared bankruptcy by surprise.3

It all started when an article in the South Florida Sun-Sentinel made it into a section on its own site called “Popular Stories: Business.” Although some observers suspected deliberate manipulation, the Wall Street Journal suggested the sudden popularity of the article might have been an honest mistake—with many people searching for information about travel delays due to storms.4 These searches, many possibly related to United Airlines and Florida, might have led to the older article. Because the Sun-Sentinel is not a publication with the scale or popularity of a national broadsheet, it likely required far fewer views for an article to reach the “popular” section. As reported by the Wall Street Journal, a spokesman for the Sun-Sentinel claimed there was “no indication of fraud.”

An important fact is that the story—although originally published in December 2002—had no date. That meant that when Google News’ algorithms “saw” the story it, according to Wired, “...assigned a current date to the piece, which then resulted in the article being placed in the top results of Google News.”5

After it was placed in Google News, the article gained a wider audience. Although the article never made it on the front page, it was noticed by Income Securities Advisors (ISA), which is a “third-party” contributor to Bloomberg Professional.6 At 10:53 a.m., a reporter at ISA posted the news to Bloomberg.

This led to chaos. Because Bloomberg Professional is a widely used financial news source, large numbers of market participants were exposed to this false news, which led to the sharp 76% drop. Bloomberg later corrected the report. The stock ended down 11% for the day but recovered most of the value lost in the crash.

Although a United spokeswoman called the rumors “completely untrue,” no corrective action was taken by the exchange:7

“In a statement, NASDAQ said all trades during the chaotic period from 10:55—two minutes after the story was posted—to 11:08 would stand and had no further comment.”8

This episode reinforces the fact that as a trader, you cannot expect the exchanges to bail you out due to market errors. As discussed in Chapter 8, “Crashes, Trading Glitches, and Fat-Finger Trades,” exchanges and regulators thus far have reversed trades in a relatively capricious and unpredictable fashion.

The good news about demonstrably false rumors like this is that, although the stock price may experience a sharp swift fall, the recovery is also usually just as swift. The average investor in United stock would likely not have been able to trade off the Bloomberg headline. However, in one sense, this investor didn’t need to. Although UAL was down 11% for the day, the stock recovered most of its value lost in response to the false story. Short of being stopped out (which is a real possibility), the average investor would have not borne the brunt of a fall like this.

Nokia Misdials

Rumors about new products can drive a company’s stock price. This is especially true for technology companies. For instance, on Wednesday, September 5, 2012, Nokia announced two new smartphones, the Lumia 920 and Lumia 820. These phones, designed to run the yet-to-be-released Windows Phone 8 OS, were critically important for the company. Nokia had been bleeding market share, especially at the high end—where the highest profit margins are found. Although still a contender at the low end, especially in developing countries, Nokia was far from the mobile phone juggernaut it used to be. In the face of declining market share, profits, and fierce competition from Apple’s iPhone and Samsung’s Galaxy S series of smartphones, Nokia needed a breakthrough.

A series of leaks and rumors helped to hype up the product announcement. On August 22, Bloomberg reported that Verizon, the largest mobile phone carrier in the United States, might receive a Nokia Windows Phone by the end of the year.9 On August 31, phonearena.com claimed the phone might have a 21-megapixel PureView camera.10 Even Nokia executives got in on the game. On August 16, Nokia’s executive vice president of sales and marketing, Chris Weber, tweeted:

“Samsung take note, next generation Lumia coming soon. #nokia”11

Vlad Savov at The Verge noted:12

“...It conveys a confidence that’s either backed up by what he’s seen behind closed doors or inflated by Nokia’s desperation to deliver a truly market-leading device.”

This flurry of speculation and hype around the devices contributed to movement in Nokia’s stock price, which was up 92% from July 17 to August 27.13

Anticipation and expectation were clearly high. But as Stephen Elop, CEO of Nokia, announced the phones in New York on September 5, Nokia’s stock began to tank. It fell more than 16% by the end of the day.14 In some ways, this was a paradoxical event.

Nokia’s new phones, especially the flagship Lumia 920, had many cutting-edge features that were well received by the tech media. However, even an advanced camera, wireless charging, and a touch screen that could be used with gloves could not save Nokia stock. So what went wrong?

Specifics. Nokia announced a great set of phones, but had no information on release dates, pricing, or specific carrier partners. This ambiguity sent fear through the market. Although Nokia promised the phone would be released in the fourth quarter, Vlad Savov at The Verge put it bluntly:

“Today needed to be about delivery...Instead Nokia ...[excited] fans with an array of sweet new features...but [failed] them by offering no firm release details.”15

The Verge later reported that this delay might have been due to Microsoft finishing up the Windows Phone 8 operating system.16 There was also a minor scandal relating to Nokia’s much-hyped camera technology, in which some promotional images and videos were later revealed to have been faked.17 Regardless of the cause, Nokia’s stock took the fall.

But that’s not all. Given the imminent announcement and launch of the highly anticipated—and itself hyped—iPhone 5, the possibility exists that the stock—barring a Nokia announcement of a paradigm shift in mobile technology—was in for a fall regardless of what Nokia had to offer. Ironically enough, even though Nokia’s September 5 event was designed to preempt the Apple iPhone event on the 12, Samsung, itself an Apple foe, preempted Nokia by announcing its own Windows Phone 8 phone, the Ativ S, on August 29.18 So, Nokia both lost its first announcement advantage to Samsung and—when Apple released the iPhone 5 on September 21—its first mover advantage to Apple.

However, some argue the fall might have happened almost regardless of what Nokia announced because the trading adage suggests that traders should “Buy the rumor, and sell the news.”

While referencing the Nokia fall, Douglas Ehrman at the Motley Fool Blog Network wrote:

“There is a common phenomenon in the stock market that tends to drive stocks increasingly higher into a major announcement and then much lower when the announcement is finally made....”19

As noted earlier, in many ways, the stock was primed for a fall, in a classic case of “Buy the rumor, sell the news.” Nokia stock had nearly doubled in the weeks before the announcement, when hype, leaks, and speculation were rampant. The market had already priced in an amazing phone (partially due to Nokia’s own hype machine)—and it was very difficult for Nokia to meet the market’s expectations. Anything short of amazing was thus a disappointment. So even though Nokia could not announce a release date—the stock was already primed for a fall regardless.

Hyundai Motors

Sometimes good news is overshadowed by rumors of potential bad news. Such a case happened on November 1, 2012 to Hyundai Motors when rumors that a massive mandatory recall was imminent for vehicles sold in the U.S.A. by Hyundai. The stock fell almost 4% on the Korea Exchange (KRX) despite reporting record monthly sales volume. The denial of the rumor as “groundless” by an official at Hyundai Motors failed to stop the slide.20

HBOS

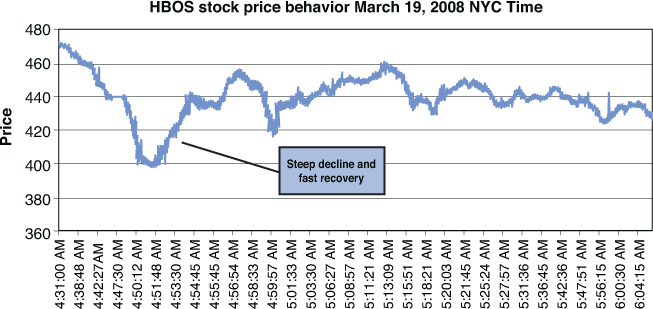

Another example of rumors severely dragging down a stock’s price is the case of HBOS—Halifax Bank of Scotland. In the midst of the global financial crisis, rumors started to circulate about HBOS’ credit-worthiness. At one point, shares fell almost 18% on March 19, 2008.21 The rumors were so devastating that the Bank of England issued a statement reassuring the market that it was not providing a bailout.22 The decline in HBOS stock price is shown in Figure 5-1. The stock bounced back after the rumors were denied but did not return to the pre-rumor level that day.

Figure 5-1. This chart illustrates the sharp break in HBOS stock price following a rumor about their credit-worthiness on March 19, 2008. The horizontal axis reflects New York City time.

Sally Dewar of the FSA had this to say about the market’s response to the rumors about British banks and the possibility of market abuse by short sellers:

“We will not tolerate market participants taking advantage of the current market conditions to commit abuse by spreading false rumours and dealing on the back of them.”23

Despite the harsh language of this statement, the FSA’s subsequent investigation of the affair found no evidence of the attempted manipulation of HBOS share prices.24 The examination concluded that although rumors negatively impacted the price of HBOS shares:

“...the FSA has not uncovered evidence that they were spread as part of a concerted attempt by individuals to profit by manipulating the share price.”25

The FSA identified several other contributing factors such as electronic trading strategies and a lack of liquidity as having exacerbated the crisis. In an article published before the end of the investigation, Forbes noted:

“The FSA admitted it had never caught anyone for this specific type of market abuse...”26

This calls into question whether, in fact, no market abuse took place or whether the FSA simply did not have the resources to catch it.

Steve Jobs’ Health

Although malicious intent is often suspected in cases where negative market rumors arise, this is not necessarily the case. The negative market rumor might simply reflect reality in many cases. Documented cases also exist of rumors being spread without any seeming financial motive but as a hoax or for a lark. For instance, on October 3, 2008, a rumor that Apple CEO, Steve Jobs, had suffered a heart attack precipitated a 5% decline in Apple’s stock price and a loss (albeit temporarily) of $4.8 billion in market cap. The rumor was spread on CNN’s iReport.com. The SEC investigated an 18-year-old man for spreading the rumor, which, as it turned out, was simply spread as a prank.27

Regardless of whether rumors were intentionally spread with malicious intent or were unfortunate coincidences exacerbated by machine trading, liquidity problems, or something else, the result is the same: Rumors can and will affect stock prices.

Audience Inc.

There are other serious cases of rumors causing massive moves in stocks. On Tuesday, January 29, 2013, shares of Audience Inc. crashed 25% after a Twitter account pretending to be Muddy Waters (the famous short-selling firm) announced that Audience was being investigated by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) for fraud. The error was quickly noticed and trading was halted by the Nasdaq OMX Group. However, the damage was done. In a two-minute period from 2:19 to 2:21, around 300,000 shares were traded and the stock lost 1/4th of it’s value.28

The rumor was quickly refuted by the real Muddy Waters Twitter account, and trading was halted for only 5 minutes. Ironically enough, Audience ended the day up 4.5% after this hoax episode blew over.29

Some market participants claimed that computer systems which scour the internet for breaking information may have contributed to the fall—by falsely trading off the incorrect information. This raises questions about whether superfast trading systems are always superior—especially if they can be fooled by rumors.

A similar event happened the next day, January 30, 2013. A negative tweet, supposedly from a well-known short-seller, triggered an almost 10 percent drop in the stock price of Sarpeta Therapeutics Inc.30 Like the case with Audience Inc., the decline was short-lived after the short-seller in question denied sending the tweet.31

Position Announcements

Should position announcements by high-profile investors or traders matter to other market participants? Whether or not they should matter, they usually do.

“The Oracle of Omaha”

Warren Buffett, the famous value investor, made a large bet on the Chinese company BYD and saw fantastic paper returns when the stock rose fivefold in less than one year.32 It is likely that market sentiment towards BYD significantly improved when given the stamp of approval from the “Oracle of Omaha.”

Guy Spier, principal at Aquamarine Funds LLC of New York, put it this way—with panache:

“When Warren Buffett says the sun shines out of somebody’s backside, it’s worth paying attention.”33

That reputation was well earned. In the depths of the global financial crisis, Buffett made a large investment in Goldman Sachs preferred stock, which Businessweek claimed “may save Goldman Sachs.” Businessweek noted:

“Within 14 hours of Buffett’s ride to the rescue of Goldman Sachs...[its] stock offering, for 40.65 million shares at $123 each, raised twice what Goldman managers originally expected.”34

This investment was instrumental in saving Goldman despite the fact that it had to pay greatly for Buffett’s rescue. Forbes noted that its high cost was also the reason why Goldman sought to end it as soon as possible:

“...Buffett’s 2008 investment...saved Goldman...But...Goldman...couldn’t wait to breakup... [because it] cost Goldman $1,369,863 each day in dividends...”35

Warren Buffett’s stamp of approval was so valuable that Goldman was willing—some would argue forced—into accepting such an expensive deal. But not all high-profile players in the market bring companies up with their actions—some help bring share prices down.

David Einhorn

On October 17, 2011 in a lengthy 100+ slide presentation, hedge fund manager David Einhorn sharply criticized Green Mountain Coffee (GMCR), which had been one of 2011’s best-performing stocks.36

In response to this sharp criticism, the stock fell 10% on the same day. Of course, Mr. Einhorn was not just criticizing Green Mountain as a disinterested market watcher. His own Greenlight Capital was reported by the Wall Street Journal to have a short position in GMCR. His presentation’s second slide noted appropriately that “Greenlight has an economic interest in the price movement of the securities discussed in this presentation.”37 Clearly, the market knew he had an economic interest in his own presentation.

However, the self-interest did nothing to dilute his message, and in fact might have made it even more persuasive. Indeed, he was so sure of the flaws in the company that he was willing to risk his own and his investors’ capital.

Carl Icahn

The knowledge that an important investor has a position in a particular stock can cause shocks across the market. This might be because these individuals have superior research about a stock or, more likely, it is because they have demonstrated superior investment performance in similar situations in the past, which enhances their credibility.

After it was revealed that Carl Icahn, the famous activist investor, had acquired a 10% stake in Netflix, shares surged 13% in one day.38 Netflix shares were called “undervalued” by Mr. Icahn in a securities filing. Fox Business noted:

“The move is a sign that Icahn, an activist investor who often demands change in companies he buys into, sees value in Netflix.”39

Due to Mr. Icahn’s fame and track record, the market agreed.

Muddy Waters

Sometimes reports from seemingly obscure players can have a huge impact on the market. For instance, on June 2, 2011, Muddy Waters LLC, until that time an obscure research firm, released a damning report accusing Sino-Forest Corporation of being a “multibillion-dollar Ponzi scheme.”40 Shares of the company fell 21% on June 2 and 64% on June 3. By June 21, shares of the company had fallen 91%.41 Figure 5-2 shows the price action.

(Reprinted with permission from Yahoo! Inc. 2013 Yahoo! Inc. [YAHOO! and the YAHOO! logo are trademarks of Yahoo! Inc.])

Figure 5-2. This chart depicts the behavior of SinoForest’s stock price after Muddy Waters’ allegations of fraud.

Like Einhorn’s disclosed self-interested report on GMCR, Muddy Waters had disclosed short positions on Sino-Forest. However, these allegations were so serious that the market didn’t worry about the disclosed conflict of interest. The entire affair turned even more dramatic when the financial press noted that famous hedge fund manager John Paulson’s Paulson & Co. had a significant stake in Sino-Forest. It was sold by June 17 at a large loss.

By April of 2012, Sino-Forest filed a $4 billion defamation lawsuit against Muddy waters—the same day they filed for bankruptcy.42

Muddy Waters was back in the news in late November 2012 when Carson Block, head of Muddy Waters, gave a presentation—on Singaporean commodity trading firm Olam—in London. The Financial Times reported:

“Mr. Block’s presentation accuses Olam of accounting “shenanigans” and over-indebtedness, which, he says, mean the company is hugely overvalued.”43

In response, Olam shares fell 17% in New York over-the-counter trading—although they later recovered some of their losses. This is partially due to the fact that Olam completely rejected Muddy Waters’ claims and even went so far as to sue Mr. Block and Muddy Waters for libel in Singaporean court.44

Shorted Companies Bite Back

Many companies that attract heavy short selling contend that their firms are fine and the shorts are trying to destroy the firm. In many cases, the shorts are simply delivering a message that other investors also share—the company is poorly managed and should be trading lower. The executives and stockholders of the affected firms may not have liked the message being sent but it was factual. Sometimes the companies that are shorted bite back.

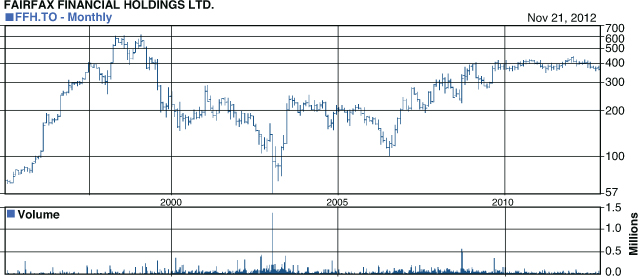

A seemingly bizarre case in point is Fairfax Financial. The company argued that two prominent hedge funds engaged in a dirty tricks campaign against it, including spreading negative market rumors, and colluded with an investment analyst at an investment bank to induce an unwarranted price decline in Fairfax Financial stock.45 The hedge funds in question denied the allegations. Fairfax Financial sued the hedge funds and others for $5 billion. The stock price rose sharply after the lawsuit was filed but a New Jersey state court judge eventually dismissed the suits against the defendants.46 The price action in Fairfax Financial’s stock price is reflected in Figure 5-3.

(Reprinted with permission from Yahoo! Inc. 2013 Yahoo! Inc. [YAHOO! and the YAHOO! logo are trademarks of Yahoo! Inc.])

Figure 5-3. This chart depicts the behavior of Fairfax Financial’s stock price following its filing of a lawsuit accusing some hedge funds of engaging in a dirty tricks campaign against it.

Trading Lessons

As stated in the first chapter, trading is about decision-making, usually under conditions of uncertainty. You don’t have all the facts and yet you have to make a decision. If you have a position on and a credible rumor suggests that the position is wrong, get out. You can always get back in if the rumor turns out to be wrong, but you can’t always get out at the current price if the rumor proves to be true. The cost of getting out is the cost of doing a transaction plus any adverse change in price if you have to get back in again.

The advice embodied in the trading adage “buy the rumor and sell the news” illustrates how partial information often is more important than facts. Demonstrably false rumors may have a much shorter impact window on market prices than rumors that turn out to be true.

A special category of rumors is those that are self-fulfilling prophecies. The perfect case in point is the collapse of Bear Stearns. Investors’ belief that Bear was unable to fund itself increased the interest rates Bear needed to pay to borrow money and decreased the willingness of market participants to lend to Bear Stearns. Confidence lost is not easily regained.

The announcement that a high-profile trader or investor has a long or short interest in a particular company can exert a significant impact on market prices. The effect is probably more pronounced on the downside. Moreover, as illustrated earlier in Figure 5-1 by the behavior of Sino-Forest’s stock price, the impact can feed on itself.

Endnotes

1. Chambers, M., and S. Moran, “Hoaxer Snares Coalmining Investors, Gullible Media,” The Australian, January 8, 2013. White, A., and A. Main, “Probe into Whitehaven Hoax,” The Australian, January 8, 2013.

2. Chambers, M., and S. Moran, “Hoaxer Snares Coalmining Investors, Gullible Media,” The Australian, January 8, 2013.

3. Smith, A., “UAL Ends Lower after Denying Rumors.” CNN Money. September 8, 2008. http://money.cnn.com/2008/09/08/news/companies/united_airlines/index.htm.

4. Ovide, S., and J.E., Vascellaro, “UAL Story Blame Is Placed on Computer.” Wall Street Journal. September 10, 2008. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122100794359017593.html.

5. Zetter, K., “Six-Year-Old News Story Causes United Airlines Stock to Plummet — UPDATE Google Placed Wrong Date on Story.” Wired. September 08, 2012. http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2008/09/six-year-old-st/.

6. Ahrens, F., “2002’s News Yesterday’s Sell-Off.” Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/09/08/AR2008090803063_2.html.

7. Smith, A., “UAL Ends Lower after Denying Rumors.” CNN Money. September 8, 2008. http://money.cnn.com/2008/09/08/news/companies/united_airlines/index.htm.

8. Ahrens, F., “2002’s News, Yesterday’s Sell-Off.” Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/09/08/AR2008090803063_2.html.

9. Bass, D. and S. Moritz, “Verizon Is Said to Offer Nokia Windows 8 Phone This Year.” Bloomberg News. August 22, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-08-21/verizon-is-said-to-offer-nokia-windows-8-phone-this-year.html.

10. Victor, H., “Nokia Lumia 820, 920 Leak Out: PureView Coming to Windows Phone.” phoneArena.com. August 31, 2012. http://www.phonearena.com/news/Nokia-Lumia-820-920-leak-out-PureView-coming-to-Windows-Phone_id33931.

11. Price, E., “Nokia: ‘Samsung Take Note, Next Generation Lumia Coming Soon.’” Mashable. August 16, 2012. http://mashable.com/2012/08/16/nokia-chris-weber-samsung/.

12. Savov, V., “Nokia sales chief warns Samsung to ‘take note’ of next generation Lumia.” The Verge. August 16, 2012. http://www.theverge.com/2012/8/16/3246517/nokias-chris-weber-samsung-trash-talk.

13. Jubak, J.J., “Should you buy on Nokia’s drop?” MSNMoney. September 5, 2012. http://money.msn.com/top-stocks/post.aspx?post=0d315488-2fe2-4dd1-859d-4c10867fd0c6.

14. Ray, T., “Nokia Off 16%: Time Will Tell for Lumia, Say RBC, Argus, Oppenheimer” Barron’s September 5, 2012. http://blogs.barrons.com/techtraderdaily/2012/09/05/nokia-off-16-proof-will-be-in-partnerships-says-rbc/.

15. Savov, V., “Nokia starts over, again: stunning new phones, no release date in sight.” The Verge, September 5, 2012. http://www.theverge.com/2012/9/5/3294380/nokia-reboot-windows-phone-8-no-release-date/in/2865586.

16. Warren, T., “As Nokia waits, Microsoft fights to keep Windows Phone 8 on schedule.” The Verge. September 11, 2012. http://www.theverge.com/2012/9/11/3314650/windows-phone-8-schedule-delays-release.

17. Hollister, S., “Nokia’s PureView still photos also include fakes (update: Nokia confirms).” The Verge. September 6, 2012. http://www.theverge.com/2012/9/6/3297878/nokias-pureview-still-photos-also-include-fakes/in/3057769.

18. Bohn, D., “Samsung Ativ S officially announced: Windows Phone 8 with a 4.8-inch 720p display.” The Verge. August 29, 2012. http://www.theverge.com/2012/8/29/3277005/samsung-ativ-s-windows-phone-8.

19. Ehrman, D., “Nokia: Buy the Rumor, Sell the News.” Motley Fool. September 5, 2012. http://beta.fool.com/dsewrites/2012/09/05/nokia-buy-rumor-sell-news/11320/.

20. Nam, K-H., and J. Lee, “Recall Rumors Send Hyundai Motors’ Shares Plunging.” MK Business News, November 1, 2012. http://news.mk.co.kr/newsRead.php?rss=Y&sc=30800006&year=2012&no=716279&sID=308.

21. Reed, S., “Brit Market Watchdog Slams Rumors.” Businessweek. March 19, 2008. http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2008-03-19/brit-market-watchdog-slams-rumorsbusinessweek-business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice.

22. Mckeigue, J., “HBOS’s Hornby Shuts-Up Rumor Mongers.” Forbes. March 26, 2008. http://www.forbes.com/2008/03/25/hornby-hbos-fsa-face-markets-cx_jm_0325autofacescan02.html.

23. Aldrick, P., “FSA to launch probe as rumours hit UK banks.” Telegraph. March 19, 2008. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/2786534/FSA-to-launch-probe-as-rumours-hit-UK-banks.html.

24. Kennedy, S., “FSA finds no evidence of HBOS manipulation.” WSJ MarketWatch. August 01, 2008. http://articles.marketwatch.com/2008-08-01/news/30705281_1_insider-trading-fsa-rumors.

25. Ibid.

26. Mckeigue, J., “HBOS’s Hornby Shuts-Up Rumor Mongers.” Forbes. March 26, 2008. http://www.forbes.com/2008/03/25/hornby-hbos-fsa-face-markets-cx_jm_0325autofacescan02.html.

27. Fox News, “Report: Steve Jobs Heart-Attack Hoax a Teen Prank.” Fox News, October 28, 2008. www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,443962,00.html.

28. McCrank, J., and D. Gaffen, “Hoax tweets send Audience shares atwitter,” Reuters News, January 29, 2013. http://mobile.reuters.com/article/idUSBRE90S11T20130129?irpc=932.

29. Ibid.

30. Vlastelica, R., “Second Twitter Hoax in Two Days Smacks Another Stock,” Reuters News, January 30, 2013. http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/01/30/sarepta-idUSL1N0AZFCV20130130

31. Ibid.

32. Bloomberg News, “Buffett Posts $1 Billion Profit on China Hybrid Carmaker BYD.” Bloomberg. July 31, 2009. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a5nT9dttOs7w.

33. Ibid.

34. Weber, J., “Warren Buffett, Goldman’s White Knight.” Bloomberg Businessweek. http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2008-09-24/warren-buffett-goldmans-white-knightbusinessweek-business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice.

35. Touryalai, H., “Warren Buffett Is Finally Out of Goldman Sachs’s (sic) Hair.” April 18, 2011. Forbes.com. http://www.forbes.com/sites/halahtouryalai/2011/04/18/warren-buffett-is-finally-out-of-goldman-sachss-hair/.

36. Eder, S., and A. Or, “Manager Blasts Green Mountain.” Wall Street Journal, October 18, 2011. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203658804576637481526849372.html.

37. Platt, E., “Here’s David Einhorn’s Presentation That Absolutely Destroys Green Mountain Coffee.” Business Insider. October 19, 2011. http://www.businessinsider.com/gaap-uccino-the-story-of-keurigs-coffee-dominance-2011-10?op=1.

38. Booton, J., “Icahn Acquires 10% Stake in Netflix.” October 31, 2012. Fox Business. http://www.foxbusiness.com/technology/2012/10/31/icahn-acquires-10-stake-in-netflix/.

39. Ibid.

40. Austen, I., “Canada Halts Trading in Sino-Forest of China.” New York Times Dealbook. August 26, 2011. http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2011/08/26/canadian-regulators-order-sino-forest-executives-to-resign/.

41. Bilt, K., C. Donville, and M. Walcoff, “Paulson May Deal Clients $720 Million Loss.” Bloomberg. June 21, 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-06-21/paulson-dumping-sino-forest-may-deal-clients-720-million-loss.html.

42. O’Toole, J., “Sino-Forest Sues Muddy Waters for Defamation.” CNNMoney, April 3, 2012. http://money.cnn.com/2012/04/02/markets/sino-forest-muddy-waters/index.htm.

43. Jones, S., “Hedge Fund Short Sellers Follow Their Star.” Financial Times. November 21, 2012.

44. Grant, J., “Olam launches Muddy Waters libel case.” Financial Times, November 21, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/03f3e9e8-33ce-11e2-9ae7-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2D0N9a08S.

45. White, B., “New Twist to Fairfax Financial.” Financial Times, November 3, 2006. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/d1d8086c-6adf-11db-83d9-0000779e2340.html#axzz2Cv4vwN8l.

46. Voreacos, D. and A. Effinger, “Fairfax Case Against Morgan Keegan, Exis Dismissed.” Bloomberg Businessweek, September 13, 2012. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2012-09-12/fairfax-lawsuit-against-morgan-keegan-exis-dismissed-by-judge.