8. Crashes, Trading Glitches, and Fat-Finger Trades

“It is a socialist idea that making profits is a vice; I consider the real vice is making losses.”

—Winston Churchill1

Sudden, large changes in prices periodically occur in financial markets. Many of these large price moves reflect reaction to news as financial theory would predict. However, some of the most extreme price moves—akin to “black swans” in popular parlance—reflect more the behavior of traders or poorly designed market structures than the arrival of new fundamental information. Ironically, this means that some of the biggest moves in the market are in fact, mistakes. These trading-induced black swans have important implications for market participants and policymakers alike. Although these moves cannot be predicted, the potential for such large price moves might affect how you trade. This chapter assesses some of the trading lessons from these episodes.

The May 6, 2010 “Flash Crash”

What if you could lose $862 billion dollars in 20 minutes?2

On May 6, 2010, a large automated sell order in the e-mini S&P 500 stock index futures market triggered a sudden selloff in stock index futures, which quickly spread to individual stocks. The sudden shift of selling from one market to the next in rapid succession demonstrated the interrelatedness of the U.S. stock and equity derivative markets in dramatic fashion. This was not only a sharp decline in the overall market—it was an insidious and swift blow to the thousands of individual stocks comprising the U.S. market.

The decline was made worse by the fact that the stock market was already down significantly before the flash crash occurred. The May 6, 2010 flash crash saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average suddenly fall more than 600 points in less than five minutes only to recover most of the loss within minutes. About 6% of the total value of the U.S. stock market was wiped out in moments without any apparent reason, only to recover minutes later. When you factor in the market already being down, the picture becomes even worse. At the low of the day, the market had fallen by a historic 998.5 points.3 A joint Commodity Futures Trading Commission and Securities and Exchange Commission (CFTC-SEC) Task Force examined the episode and recounted the events that day as follows:

“On May 6, 2010, the prices of many U.S.-based equity products experienced an extraordinarily rapid decline and recovery. That afternoon, major equity indices in both the futures and securities markets, each already down over 4% from their prior-day close, suddenly plummeted a further 5%–6% in a matter of minutes before rebounding almost as quickly.

“Many of the almost 8,000 individual equity securities and exchange traded funds (“ETFs”) traded that day suffered similar price declines and reversals within a short period of time, falling 5%, 10% or even 15% before recovering most, if not all, of their losses. However, some equities experienced even more severe price moves, both up and down. Over 20,000 trades across more than 300 securities were executed at prices more than 60% away from their values just moments before. Moreover, many of these trades were executed at prices of a penny or less, or as high as $100,000, before prices of those securities returned to their “pre-crash” levels.

“By the end of the day, major futures and equities indices “recovered” to close at losses of about 3% from the prior day.4

The joint CFTC-SEC Task Force Report attributed the decline to an order by a fundamental trader to sell 75,000 e-mini S&P 500 stock index futures contracts without price or time limits. So no matter how low the price got, the trader would keep selling until their entire position was liquidated. The trader used an algorithm that increased the amount of sell orders hitting the market as trading volume increased. As a result, if market activity spiked, the trader would try to sell more—in this case, it exacerbated the crash. That’s because the large sell order created an imbalance between buy and sell orders and prompted a large adjustment in prices. The CFTC-SEC Task Force Report described the events:

“May 6 started as an unusually turbulent day for the markets....Around 1:00 p.m., broadly negative market sentiment was already affecting an increase in the price volatility of some individual securities....By 2:30 p.m., the S&P 500 volatility index (“VIX”) was up 22.5 percent from the opening level, yields of ten-year Treasuries fell as investors engaged in a “flight to quality,” and selling pressure had pushed the Dow Jones Industrial Average (“DJIA”) down about 2.5%....At 2:32 p.m., against this backdrop of unusually high volatility and thinning liquidity, a large fundamental trader (a mutual fund complex) initiated a sell program to sell a total of 75,000 E-Mini contracts (valued at approximately $4.1 billion) as a hedge to an existing equity position...via an automated execution algorithm (“Sell Algorithm”) that was programmed to feed orders [tied to] trading volume calculated over the previous minute, but without regard to price or time....However, on May 6, when markets were already under stress, the Sell Algorithm...executed the sell program extremely rapidly in just 20 minutes.5

The report noted that high-frequency traders (HFTs), fundamental futures traders, and cross-market arbitrageurs between the equity option and futures markets provided the initial liquidity. However, when the HFT firms reached their relatively small maximum inventory levels, they started to sell. This increased the rate of sell orders from the fundamental trader’s sell algorithm that, in turn, sparked even more selling.6 Given that many HFT firms act as market makers, the lack of real order flow from fundamental buyers led HFT firms to sell to each other without significantly increasing their overall holdings. Indeed, the report noted that HFT firms increased their net holdings by only 200 stock index futures contracts despite trading thousands of contracts. The HFTs did not act as a buffer for the order imbalance but simply made a market all the way down without significantly adding to their risk. The machines were able to move fast enough to essentially dodge the crash. The CFTC-SEC Task Force Report described the price action:

“The Sell Algorithm used by the large trader responded to the increased volume by increasing the rate at which it was feeding the orders into the market, even though orders that it already sent to the market were arguably not yet fully absorbed....The combined selling pressure from the Sell Algorithm, HFTs and other traders drove the price of the E-Mini down approximately 3% in just four minutes from the beginning of 2:41 p.m. through the end of 2:44 p.m. During this same time cross-market arbitrageurs who did buy the E-Mini, simultaneously sold equivalent amounts in the equities markets, driving the price of SPY also down approximately 3%.

“Still lacking sufficient demand from fundamental buyers or cross-market arbitrageurs, HFTs began to quickly buy and then resell contracts to each other—generating a “hot-potato” volume effect as the same positions were rapidly passed back and forth. Between 2:45:13 and 2:45:27, HFTs traded over 27,000 contracts, which accounted for about 49 percent of the total trading volume, while buying only about 200 additional contracts net....As liquidity vanished, the price of the E-Mini dropped by an additional 1.7% in just these 15 seconds, to reach its intraday low of 1056. ...In the four-and-one-half minutes from 2:41 p.m. through 2:45:27 p.m., prices of the E-Mini had fallen by more than 5% and prices of SPY suffered a decline of over 6%....”7

The crash in stock index futures prices ended after the Chicago Mercantile Exchange stopped trading for five seconds.8 The crash in stock index futures prices stopped because of a trading halt. However, by this time, the selloff had already spilled over to the cash stock market where it caused significant short-term damage. The CFTC-SEC Task Force Report noted:

“Between 2:40 p.m. and 3:00 p.m., approximately 2 billion shares traded with a total volume exceeding $56 billion. Over 98% of all shares were executed at prices within 10% of their 2:40 p.m. value. However, as liquidity completely evaporated in a number of individual securities and ETFs, participants instructed to sell (or buy) at the market found no immediately available buy interest (or sell interest) resulting in trades being executed at irrational prices as low as one penny or as high as $100,000. These trades occurred as a result of so-called stub quotes, which are quotes generated by market makers (or the exchanges on their behalf) at levels far away from the current market in order to fulfill continuous two-sided quoting obligations even when a market maker has withdrawn from active trading. The severe dislocations observed in many securities were fleeting....By approximately 3:00 p.m., most securities had reverted back to trading at prices reflecting true consensus values. Nevertheless, during the 20-minute period between 2:40 p.m. and 3:00 p.m., over 20,000 trades (many based on retail-customer orders) across more than 300 separate securities, including many ETFs, were executed at prices 60% or more away from their 2:40 p.m. prices....”

All the trades occurring at extreme prices were subsequently canceled. However, the fact that the flash crash occurred at all left many observers wondering why the system was so fragile. Was it really possible that one trader could cause this much economic destruction? On an individual basis it also exposed the dangers of having open limit orders or stop-loss orders on the books. With such a huge but brief fall, many people were “stopped out” of trades that would have otherwise been profitable—only to see prices rebound in mere minutes.

Trading Lessons

What lessons can you draw from the May 6, 2010 flash crash? They include:

• HFT firms did not cause the crash, nor did their actions help stop it.

• The absence of designated market makers meant that the market was largely dependent upon standing limit buy orders, fundamental buyers entering the market, or arbitrage traders to provide liquidity. If a cascade of selling hit the market, HFT firms would not provide sufficient liquidity during a crisis. As the CFTC-SEC Report pointed out, HFT firms added only 200 E-Mini stock index futures contracts to their positions after prices started to fall.

• Even though the HFTs avoided the worst of the crash, the mechanical nature of the cascade of selling is apparent from the fact that a trading halt of only five seconds was sufficient to stop it. After the death spiral was only momentarily halted, the spiral was itself destroyed.

• Although the trading halt stopped stock index futures prices from falling further and prompted them to start rising, stock prices continued to fall in the cash market. Markets are linked but they might not move synchronously.

• Although many trades were canceled, the cascade of selling triggered additional selling as many stop loss orders were set off.

• Somewhat ironically, having open stop-loss orders in the market can be dangerous.

Other Flash Crashes

Unfortunately, the May 6, 2010 flash crash was not a one-off event. Even faster and sometimes larger flash crashes occurred in the commodity futures markets during 2011. For instance, on March 1, 2011, May delivery cocoa futures fell 12.5% in less than a minute on the Intercontinental Commodity Exchange (ICE) only to quickly rebound and close down 2.5% for the day. Like the May 6, 2010 flash crash, the presumed culprit was a large sell order. The sharp decline and subsequent rebound caused ICE officials to cancel trades much like what occurred in the aftermath of the flash crash in equity prices.

The decline in cocoa futures prices was slow compared with the nearly 6% plunge in March sugar futures prices in a single second on February 3. The presumed cause was algorithmic trading. On June 8, 2011, July delivery New York Mercantile Exchange natural gas futures prices suddenly fell more than 8% in after-hours trading only to recover in a few seconds. Algorithmic trading was blamed.

Sudden, seemingly inexplicable price moves have occurred in the world’s largest market—the currency market—as well. The nature of currency trading means that a sharp drop in the exchange rate of one currency also means a sharp increase in the value of the currency it is being traded against. The March 11, 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and subsequent Fukushima nuclear disaster precipitated one such large move. On March 17, 2011, the Japanese yen suddenly jumped 4.6% against the dollar in less than half an hour before falling back. The presumed culprits were automated stop-loss trades. Some observers believe that this sudden sharp rise in the yen was one of the primary factors that precipitated a surprise currency market intervention by G-7 central banks on March 18, 2011. Despite the substantial increase in the value of yen (or, equivalently, decrease in the value of the dollar) and the short time period over which it occurred were similar to that of the flash crash but, unlike the equity flash crash, none of the yen trades were canceled.

October 19, 1987 Stock Market Crash

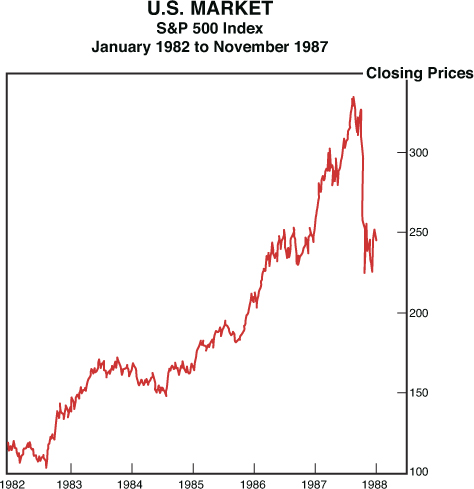

Crashes are not unique to electronically traded stocks and futures as the stock market crashes of October 1929 and 1987 clearly demonstrate. Yet, past market crashes share certain characteristics in common with the more recent flash crashes. For instance, on Monday, October 19, 1987, the U.S. stock market fell 23% as measured by the S&P 500 stock index while the stock index futures market fell almost 29%. The rise of the S&P 500 stock index from the bull market that began in August 1982 to its high in August 1987 is depicted in Figure 8-1, reproduced from the 1988 Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms. The October 1987 crash in stock prices is clearly visible. However, the cause of the crash is still unknown.9 The decline that day is recounted in the report of the Presidential Task Force chaired by Nicholas Brady:

(Reproduced from the 1988 Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms.)

Figure 8-1. This chart depicts the bull market in U.S. equities from 1982 to 1987.

“All told, Monday, October 19 was perhaps the worst day in the history of U.S. equity markets. By the close of trading, the Dow index had fallen 508 points, almost 23 percent, on volume of 604 million shares worth just under $21 billion. Even worse, the S&P 500 futures had fallen 29 percent on total volume of 162,000 contracts valued at almost $20 billion.

“The record volume was concentrated among relatively few institutions...The contribution of a small number of portfolio insurers and mutual funds to the Monday selling pressure is even more striking. Out of total NYSE sales of just under $21 billion, sell programs by three portfolio insurers made up just under $2 billion. Block sales of individual stocks by a few mutual funds accounted for another $900 million. About 90 percent of these sales were executed by one mutual fund group. In the futures market, portfolio insurer sales amounted to the equivalent of $4 billion of stocks or 34,500 contracts, equal to over 40 percent of futures volume, exclusive of locals’ transactions; $2.8 billion was done by only three insurers.... Huge as this selling pressure from portfolio insurers was, it was a small fraction of the sales dictated by the formulas of their models.”10

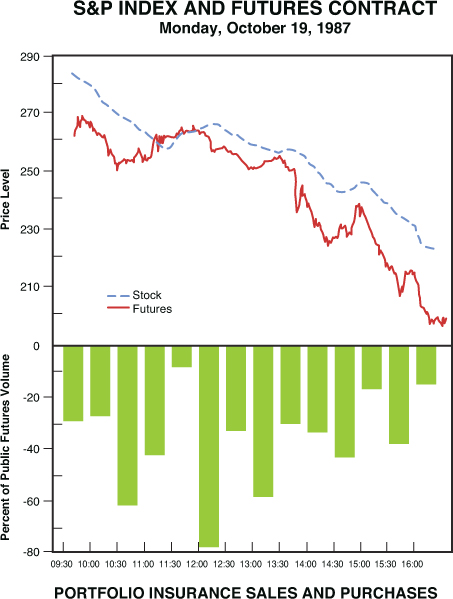

Put differently, only a handful of market participants were responsible for most of the selling that day. Also, after the selling started, the mad rush by some market participants (such as portfolio insurers) to hedge their positions reinforced a spiral of falling prices. In addition, were it not for the failure of humans to execute the trades called for by portfolio insurance models, the selling would have been even greater. The tug of war between buyers and sellers of stocks that day is instructive and is missed if you look only at the change in closing prices or the range of prices during the day. The intraday price action is reflected in Figure 8-2 (a one-minute chart for the S&P 500 stock index and December 1987 S&P 500 stock index futures price that the Task Force published in its Report as Figure 22). It also reported the fraction of stock index futures trading volume associated with portfolio insurance strategies. This figure shows that after an initial sharp break at the open, the market stabilized for a short time before breaking again then remaining comparatively stable for about two hours before falling again, rising, falling sharply, rising, and falling again.

(Reproduced from the 1988 Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms.)

Figure 8-2. This chart depicts the intraday price action of S&P 500 stock index and December 1987 Delivery S&P 500 stock index futures contract on Monday, October 19, 1987.

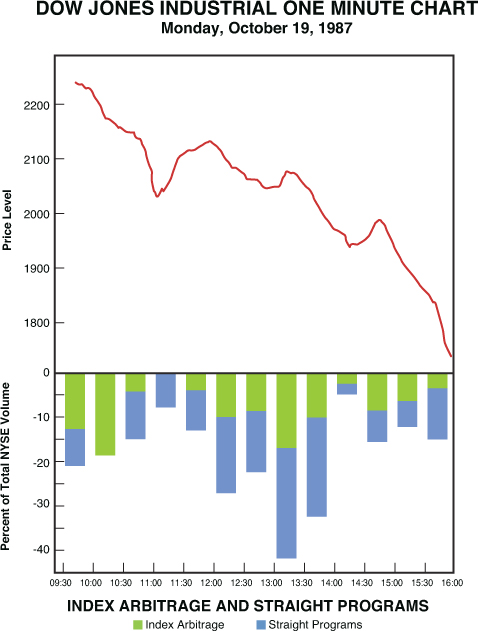

The point is that the full extent of the ultimate price move was not immediate. Prices continued to bounce around, albeit generally at lower levels throughout the day. Not surprisingly, a similar pattern can be observed in the Dow Jones Industrial Average in Figure 8-3 (a one-minute chart for the DJIA that was published as Figure 23 in the Brady Commission Report). Figure 8-3 also depicts the fraction of NYSE trading volume originating from index arbitrage and straight programs on October 19, 1987.

(Reproduced from the 1988 Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms.)

Figure 8-3. This chart depicts the intraday price action of the Dow Jones Industrial Average on Monday, October 19, 1987.

The flash crash of May 6, 2010 and the stock market crash of Monday, October 19, 1987 share neither the duration nor the extent of the price decline in common. The market fell farther and stayed lower longer in the 1987 crash than in the 2010 flash crash. Rather, the commonality is that both were exacerbated, if not triggered, by what some have described as “mechanical price-insensitive selling.” In this case, mechanical price-insensitive selling does not have to refer to machines per se but simply to selling in an attempt to get out at any price.

Other Stock Market Crashes

The stock market crash of October 1987 was not limited to equity markets in the U.S. Instead, equity markets around the world fell sharply. The Brady Commission recounted the actions in international markets on October 19 before trading in New York opened as follows:

“In Tokyo, the Nikkei Index, Japan’s equivalent of the Dow, fell 2.5 percent. Investors in London sold shares heavily, and by midday the market index there was down 10 percent. Selling of U.S. stocks on the London market was stoked by some U.S. mutual fund managers who tried to beat the expected selling on the NYSE by lightening up in London. One mutual fund group sold just under $90 million of stocks in London.”11

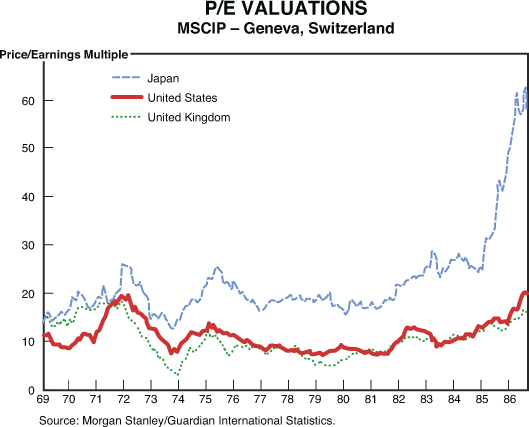

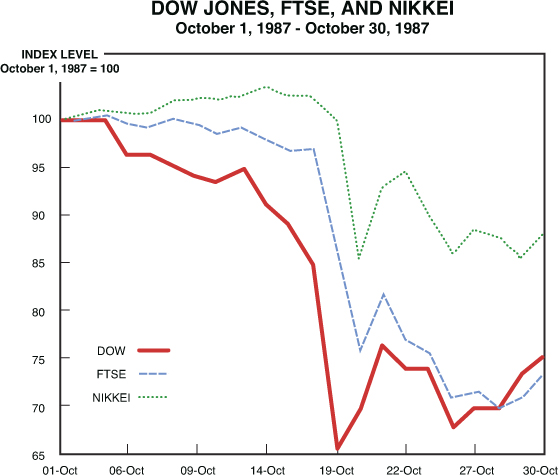

The decline in stock prices in U.S. markets triggered declines in other markets that were open at the same time and sharp declines in equity markets around the world in Asia and Europe when they reopened on Tuesday, October 20. The price action of stock markets in Britain, the U.S., and Japan are depicted in Figure 8-4 (which was published as Figure 1.1 on page II-3 in the Brady Commission Report and reproduced here) depicts the implicit price-earnings multiples in valuations in the major stock markets in the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan from 1969 through 1987. The divergence of P/E multiples used in Japan from P/E multiples in the U.S. and U.K is striking. Figure 8-5 (which was published as Figure 21 on page III-38 in the Brady Commission Report and reproduced here) depicts the relative performance of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, FTSE, and Nikkei 225 stock indices during October 1987. As is immediately apparent, the Dow Jones Industrial Average suffered the worst decline on October 19, 1987 followed by the FTSE and the Nikkei 225. Nor did the Japanese market (which is 14 hours ahead of New York) make up for it with a larger decline on Tuesday, October 20, 1987. Interestingly, major equity indexes in the U.S. and Britain ended 1987 slightly higher than they began despite the October crash. In contrast, the Japanese stock market as measured by the Nikkei 225 closed up over 18% (in local currency terms) for the year despite a crash in Japanese stock prices in October. At the time of the October 1987 stock market crash, the market capitalization of the Japanese market exceeded the market capitalization of the U.S. market. One important takeaway from these events is that markets are linked and price action in one market will affect other markets around the globe. Another important takeaway is that the U.S. stock market continues to play a vital role in shaping prices around the world.

(Reproduced from the 1988 Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms.)

Figure 8-4. This chart depicts the average price earnings multiples in the U.S., U.K., and Japan during 1969-1987.

(Reproduced from the 1988 Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms.)

Figure 8-5. This chart depicts the relative behavior of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, FTSE-100, and the Nikkei 225 during the month of October 1987.

Fat-Finger Trades

Human trader errors are another source of sharp price moves in stocks and other securities. These are known as fat-finger trades and typically arise when an exceptionally large order is inadvertently entered. Given that the inadvertent or erroneous order is usually for a single security the price action is typically confined to that security as well. This usually protects the market as a whole from these temporary mistakes. However, sometimes the price action spills into the overall market and exerts a marketwide impact. This is more likely to happen when erroneous orders for multiple securities are involved. The magnitude of the impact might be large but the duration is typically short as the fat-finger trade or trades are soon discovered. In addition to revealing human flaws, fat-finger errors often reveal weaknesses in market structure as well.

For instance, at 9:49 a.m. on Friday, October 5, 2012, a series of erroneously large sell orders from a single broker triggered an almost 16% decline on the National Stock Exchange (NSE) in India within seconds. The NSE trades stocks using an electronic limit order book where orders placed by customers are matched electronically. The rapidity and breadth of the decline led many observers to initially suspect another flash crash. Instead it turned out to be a fat-finger trade. Bloomberg News reported the events at the time:

“Trading in the Nifty and some companies stopped for 15 minutes after the 50-stock gauge tumbled as much as 16 percent. A brokerage that mishandled trades...was to blame...”12

The impact of most fat-finger trades is limited to the stock for which the erroneous order was entered. Such trades can cause large price changes. One such large change happened to Rambus, which fell 35% in midday trading due to a fat-finger trade. Bloomberg News reported on January 4, 2010:

“A series of Rambus Inc. trades that were executed about $5 below today’s average price were canceled under rules that govern stock transactions that are determined to be “clearly erroneous...”13

The canceled trades occurred during a four- to five-minute time period midday.14

Trading Glitches

As electronic trading becomes more important, the market becomes more sensitive to fat-finger trades, trading glitches, and (if there is a dearth of market makers) flash crashes. Trading glitches might arise from errors by traders (both human and machine) and interruptions to trading on exchanges.

Trader Errors: “Algos Gone Wild”

Trading glitches by traders include the fat-finger errors noted earlier. A separate category related to algorithm-induced trader errors is instructive. These are instances of “algos gone wild” and faulty software. For instance, Reuters reported on November 25, 2011 that a high-frequency trading firm was fined by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) for losing control over its trading algorithms on three occasions:

“The firm’s buying on February 3, [2010] sparked a frenzied $1 surge in oil prices late that day as the computer program sent thousands of orders per second, racking up a million-dollar loss for the firm.”15

Another article attributed the surge in oil prices to the faulty algorithm:

“...The firm’s buying frenzy also reveals how faulty computer codes, known as algorithms, can spark sharp volatility and send electronic markets spinning all in the blink of an eye...”16

This example illustrates how fat-finger trades can arise from machines. Fat-finger trades by machines may not be immediately recognized as such, which means some swings in price might be interpreted as reflecting new information instead of defective algorithms.

Another instance of “algos gone wild” occurred on August 1, 2012 when newly installed but inadequately tested software at Knight Capital mistakenly reactivated old supposedly dormant software and sent a number of unintended large buy and sell orders to the market for numerous stocks. According to Bloomberg News, the old software multiplied “stock trades by one thousand.”17 The orders roiled the market for 45 minutes as it entailed trades in millions of shares of stock. Some stocks were pushed up sharply leading the New York Stock Exchange to cancel a number of trades in six stocks that were 30 percent or more away from the opening price.18 The trading glitch ultimately resulted in a $461 million loss and devastated Knight Capital’s stock price in addition to the collateral damage caused to other stocks.19 The Financial Times reported on August 3, 2010:

“...Knight’s shares closed 62.8 percent lower at $2.58...The shares continued to slide in the after-hours trading, falling more than 17 percent to $2.15...”20

Although the preceding is not an example of a black swan event per se, it illustrates the power of trading errors on stocks affected and the potential for collateral damage to the overall market.

Apple became the largest company in the world in terms of market capitalization during 2012. Yet, even Apple’s stock could be moved by a trading glitch. The glitch in Apple shares occurred in connection with a flawed initial public offering (IPO) by BATS—an electronic exchange on Friday, March 23, 2012. The Financial Times reported that problems with the BATS IPO occurred at the same time as:

“...an accidental plunge in ...Apple.... One trade that was nearly 10 percent away from Apple’s market price caused a circuit breaker to briefly halt Apple trading...”21

There were even rumors floating on the Internet claiming that errors with the BATS IPO were in fact intentionally programmed.22

Interruptions of Trading on Exchanges

Trading halts might arise due to unforeseen events, including electrical and telecommunication outages; software issues; hardware issues; natural disasters; terrorist actions; and deaths of dignitaries (resulting in moments of silence to honor those who have passed), among other factors. For instance, the New York Stock Exchange closes to honor the life of a U.S. president upon his death. Many exchanges have experienced trading interruptions. These include the International Petroleum Exchange; Chicago Mercantile Exchange GLOBEX; Sydney Futures Exchange; SGX; Toronto Stock Exchange; Stock Exchange of Thailand; New York Stock Exchange; NASDAQ; Paris Bourse; and South African Stock Exchange among others.

Computer glitches and trading system failures are a common source of trading disruptions on exchanges. These are more frequent than you might expect. The outages range from a few minutes to a day or more, and such failures are not a feature of the distant past. For instance, the Financial Times reported on October 3, 2012:

“Nasdaq suffered its second high-profile embarrassment...when it was forced to cancel trades in Kraft Foods after a trading glitch caused...shares to soar nearly 30 percent...”23

Likewise, the Financial Times reported on November 12, 2012:

“The New York Stock Exchange suspended trading in 216 companies...for most of the trading day on Monday in the latest technology glitch to hit Wall Street....24

The ability to trade the affected stocks on other exchanges helped to minimize the damage to the public.

It would be equally misleading to give the impression that trading glitches are only a feature of the present and recent past. Trading glitches have existed for as long as markets have existed. The emphasis on electronic markets that are continuously available for trading when open coupled with increased use of algorithmic trading by market participants and market makers have highlighted such incidents and increased their impact and perhaps their frequency.

Moreover, sometimes trading glitches arise at very inconvenient times. For instance, on Tuesday, September 9, 2008, the Financial Times reported:

“A technical glitch brought share trading on the London Stock Exchange to a halt for seven hours, ...[on] what should have been one of the busiest sessions of the year...”25

Trading interruptions on exchanges are too frequent to be classified as black swan events. For example, on the same day, an unrelated technical glitch caused the ICE Brent crude oil futures market to close for two hours.

Trading glitches are a subcategory of trading interruptions. Trading interruptions routinely occur for evenings (when many markets are closed), weekends, and holidays. Unscheduled trading interruptions are especially interesting. The behavior of speculative prices following unscheduled trading interruptions provides clues for the behavior of financial market prices following a trading glitch.

Breadth of Market Affected

Trading interruptions may involve only a few securities traded on the exchange or all of them. The entire market might be shut down or only a few securities might be closed for trading. For example, on June 1, 2005, a trading glitch on the NYSE caused the entire market to close four minutes early. Two days later on June 3, 2005, the inability of some traders to enter or cancel foreign exchange (FX) futures orders led to a trading halt for about one and one-half hours on the CME for FX futures.

Depth

Sometimes traders may experience an inability to trade or a loss of certain trading functions. For example, on July 8, 2005, on the International Petroleum Exchange in London (now part of ICE), there was the loss of implied spread trade activity for an entire day.

Duration

Trading interruptions can be short-lived or long-lived. For example, the NYSE suspended trading with the advent of World War I. The NYSE was closed from July 31, 1914 to December 12, 1914. Not surprisingly, as economic theory would suggest, trading shifted to other stock markets that remained open as Silber [2005] reports.26

Timing

By definition, trading interruptions occur during market hours. However, the timing of the interruption may matter. A trading interruption during a lull in trading around holidays might have less of an impact than an interruption prior to an important economic announcement. For example, consider a glitch in the trading of Japan Government Bonds (JGBs). On June 29, 2006, a glitch in the electronic trading system at the Japan Bond Trading Co.—an interdealer bond broker—halted trading in JGBs for approximately three hours. Contemporary news accounts reported that the lack of JGB price information reduced the amount of speculation on various economic news reports.

Surprise

Trading interruptions can be unscheduled or scheduled. The assassination of President John F. Kennedy resulted in the closure of U.S. stock markets on Friday, November 22, 1963. Keeping with long-standing custom, the NYSE remained closed on Monday, November 25, 1963 for the funeral of a U.S. president.

Frequency

Trading interruptions can be a one-off event or occur frequently. For instance, on Thursday, January 11, 2007, the e-CBOT electronic trading platform that handled roughly 70% of all trades on the CBOT at the time shut down for about 45 minutes. On Friday, January 12, 2007, the e-CBOT trading platform shut down from 10:30 a.m. CST to 11:42 a.m. CST and shut down again from 1:14 p.m. CST to 1:50 p.m. CST.

Cause

Trading interruptions can be caused externally or internally. Examples of external factors include inclement weather and loss of power or terrorist actions, among others. Examples of internal factors include poorly designed trading systems, software issues, trade processing capacity, and so on. Exchanges can do little to prevent external factors beyond having backup generation and trade-matching facilities in remote locations. In contrast, many problems with trading systems may be under the control of exchanges or trading system operators.

Trading Volume

Trading interruptions in one market may increase trading in another market. For example, a trading interruption on the CME GLOBEX system for the e-mini S&P 500 stock index futures contract on Thursday, May 1, 2003 led to an increase in trading volume for the CBOT Dow Jones stock index futures contract. Similarly, the closure of the Treasury bond futures markets due to the Chicago “flood” resulted in a widening of the bid offer spread in the cash market.27

Trading Glitch Case 1: The Tokyo Stock Exchange Suspends Trading

At 8:30 a.m. on November 1, 2005, the Tokyo Stock Exchange notified market participants that it was suspending trading for an indefinite period due to a trading system malfunction. However, TSE traded futures and options markets remained open. Around 12:00 p.m. that same day, the TSE announced that it had resolved the problem and would reopen. The TSE reopened stock trading at 1:30 p.m. but allowed orders to be taken at 12:45. Given that trading was suspended during the regular morning session (at that time from 9:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m.) and the first hour of the afternoon session (at that time from 12:30 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.), this was a 90-minute trading day. The TSE suspended trading due to software issues. TSE officials attributed the “cause of the system malfunction” to a “latent bug” in an old software program. A corrected program was installed on October 13, but the old program was still operative until November 1. So how did the market behave on the day of the TSE action? The Nikkei 225 stock index rose 216.36 points or 1.92 percent in last 90 minutes of trading day.

Trading Glitch Case 2.A: The TSE Fails to Cancel Clearly Erroneous Trades

One aspect of trades on U.S. markets is that clearly erroneous trades can be canceled by the exchange where they occur. This is not true on all exchanges around the world. For instance, on November 30, 2001, a data entry error by a UBS trader resulted in an order to sell 610,000 shares of newly listed Dentsu at ¥16 each rather than selling 16 shares of Dentsu at ¥610,000 or better. Only 135,000 shares were issued in the Dentsu initial public offering (IPO) so any order in excess of the initial amount issued was clearly erroneous as would be any order at such an incredibly low price. Other traders immediately recognized this as a fat-finger trade and pounced, and 64,915 shares were sold (at around ¥405,000 per share) before the balance of the order was cancelled a couple of minutes later. Exchange price limits prevented the Dentsu shares that were offered at ¥16 from being sold at ¥16. However, at the time, the TSE had a rule that prevented orders that were being processed from cancellation so trades at prices substantially below the market were honored even though the order was clearly erroneous. The end result is that UBS lost ¥16.2 billion (or about $131 million at the time).28

Trading Glitch Case 2.B: The TSE Fails to Cancel Clearly Erroneous Trades

Unfortunately, the policy of not canceling clearly erroneous trades on the Tokyo Stock Exchange was not changed following the loss UBS suffered trading Dentsu, and another firm was ensnared in a similar transpositional error years later. At 9:27 a.m. on December 8, 2005, a transposition error by a Mizuho trader resulted in an order to sell 610,000 shares of newly listed J-Com at ¥1 each rather than selling 1 share of J-Com at ¥610,000. Despite repeated efforts by the Mizuho trader, the order could not be canceled from the TSE trading system because the order was in process. Given the extraordinarily low offer price and the fact that only 2,800 shares were issued in the J-Com IPO at ¥672,000 each, other market participants knew immediately that it was an error and rushed to take advantage of it. Again, no one was able to buy J-Com stock at 1 yen per share. Prices were constrained by exchange rules to trade no lower than ¥572,000 per share nor higher than ¥772,000. Prices immediately collapsed to the minimum and then rose to the maximum as traders attempted to squeeze the trader in trouble. The limited number of shares that were issued in the initial public offering meant that delivery could not occur for all the shares that Mizuho inadvertently sold. More than 700,000 shares of J-Com traded that day. A special settlement price of ¥972,000 was set by the TSE with the difference between purchase and selling price settled in cash. The end result was that Mizuho lost ¥40.5 billion (or about $335 million at an exchange rate of ¥120.97).

Clearly, there is plenty of blame to share in these examples. Both UBS and Mizuho should have had better order entry control systems. However, the bulk of the blame lay with the Tokyo Stock Exchange for making the cancellation of orders on clearly erroneous trades difficult.

Trading Glitch Case 3: The TSE Suspends Trading

Livedoor Co. Ltd was a Japanese internet service provider run by an unconventional Japanese executive, Takafumi Horie. The company was the result of a series of acquisitions and became embroiled in fraud allegations in early 2006. The fraud allegations precipitated a dramatic decline in the price of Livedoor shares on January 18, 2006. This caused a massive increase in trading volume. Trading was so large on January 18, 2006 that it impacted the ability of the Tokyo Stock Exchange to cope with it. The TSE estimated that trading in Livedoor accounted for 45% of total executions (not trading value) at one point.

At 2:25 p.m. on January 18, 2006, the Tokyo Stock Exchange announced that it was suspending trading in stocks, convertible bonds, and exchange bonds effective at 2:40 p.m. until the close of trading (3:00 p.m.) because the volume of orders and executions was approaching the capacity constraint. The Tokyo Stock Exchange trades futures and options markets as well, and those markets remained open. At the time, the current capacity was 4.5 million executions. The TSE requested that traders combine orders wherever possible. It also delayed the start of the afternoon session from 12:30 p.m. to 1:00 p.m. effective January 19, 2006 until further notice. It announced that it would suspend trading if the number of orders exceeded 8.5 million or the number of executions exceeded 4 million.29

On January 24, 2006, the TSE announced that it was limiting the trading period for Livedoor stock to 1:30 to 3:00 effective January 25, 2006. Trading volume remained high and increased the risk that the TSE would have to suspend trading due to capacity constraints being reached. On January 25, 2006, the TSE announced reduced trading hours for Livedoor stock to 2:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m. effective January 26, 2006. It imposed some additional restrictions on transactions such as requiring that payment for purchases of Livedoor stock were due the same day and prohibited trading in Livedoor stock on margin.

The TSE introduced another change to reduce potential strains on the capacity of its trading system by shortening the opening of the afternoon trading session. The delayed opening of the afternoon trading session from January 19, 2006 to April 24, 2006 due to concern over trade processing capacity is reminiscent of the closure of the NYSE and AMEX on 23 Wednesdays during the second half of 1968 to facilitate back office processing of trades.

Trading Lessons

So what are the trading lessons from crashes, fat-finger trades, interruptions, and trading glitches? To be sure, predicting when another flash crash or fat-finger trade will occur is extremely difficult, if not impossible. However, the increasingly electronic nature of financial markets and use of algorithmic trading by market makers and other market participants makes it more likely that such interruptions will occur—and with more frequency—absent changes in the marketplace.

Nevertheless, trading lessons emerge from an analysis of these episodes, including the following:

• The opportunity to trade comes during or immediately after the shock rather than before it in most cases. In one sense, the surprise nature of these shocks is beneficial to smaller market players because having inside information or advance knowledge is impossible. You might not be able to predict these freak events, but neither will anyone else.

• The more crowded a trade is, the greater the risk of the trade if prices start to suddenly move against your position. Those market participants who used portfolio insurance to hedge their stock market positions before the October 1987 crash exacerbated the decline in the market that day. Knowledge that many traders had portfolio insurance strategies provided a market opportunity to short the market during the crash—if you had guts enough to do so. If you can recognize a glitch or crash as it is taking place, the potential exists for you to make money.

• The uneven cancellation of trades by exchanges creates another risk for traders and would-be liquidity providers. On the one hand, it gives traders a fickle but sometimes valuable insurance policy against freak events. On the other hand its uneven application can destroy wealth of those who attempt to profit off of freak events—and off of those who lose wealth in a glitch but do not benefit from cancelled trades. Regardless of the presumably good intentions of exchanges and regulators, the seemingly capricious and fickle policies toward trade cancellation places a good deal of uncertainty in the market and also presents opportunities for abuse.

• Trading glitches, fat-finger trades, and crashes all demonstrate the importance of good loss minimization strategies. Ironically these crises—and flash crashes in particular—illustrate the dangers of some loss minimization strategies, such as the use of stop-loss orders. If you choose to forego the use of stop-loss orders, you must put into place other methods of controlling loss.

Accepting risk is the price of being a trader, and freak market shocks do happen. For instance, no one could have predicted that the U.S. market would lose $862 billion in 20 minutes and then recover. What you can do is create and stick to a plan that fits your trading style and risk profile.

Endnotes

1. http://www.drmardy.com/chiasmus/masters/churchill.shtml.

2. Childs, M., “Million-Dollar Traders Replaced with Machines Amid Cuts.” Bloomberg News. November 06, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-11-06/million-dollar-traders-replaced-with-machines-credit-markets.html.

3. Twin, A., “Glitches send Dow on wild ride.” CNN, May 06, 2010. http://money.cnn.com/2010/05/06/markets/markets_newyork/.

4. U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission and Securities Exchange Commission Joint Task Force, “Findings Regarding the Market Events of May 6, 2010.” September 30, 2010. http://www.sec.gov/news/studies/2010/marketevents-report.pdf.

5. Ibid.

6. The Report noted: “HFTs accumulated a net long position of about 3,300 contracts. However, between 2:41 p.m. and 2:44 p.m., HFTs aggressively sold about 2,000 E-Mini contracts in order to reduce their temporary long positions. At the same time, HFTs traded nearly 140,000 E-Mini contracts or over 33% of the total trading volume. This is consistent with the HFTs’ typical practice of trading a very large number of contracts, but not accumulating an aggregate inventory beyond three to four thousand contracts in either direction.” 2010 CFTC-SEC Joint Task Force Report.

7. 2010 CFTC-SEC Joint Task Force Report.

8. The Joint CFTC-SEC Task Force [2010] reported: “At 2:45:28 p.m., trading on the E-Mini was paused for five seconds when the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (“CME”) Stop Logic Functionality was triggered in order to prevent a cascade of further price declines. In that short period of time, sell-side pressure in the E-Mini was partly alleviated and buy-side interest increased. When trading resumed at 2:45:33 p.m., prices stabilized and shortly thereafter, the E-Mini began to recover, followed by the SPY.” 2010 CFTC-SEC Joint Task Force Report.

9. The Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms (commonly called the Brady Commission Report) argued: “...the market break is most significant in terms of the rapidity of the decline as opposed to the amount of the decline.... The commonly identified causes of the October break can be grouped into two categories. First are those causes that might be termed broad fundamentals—factors that could be responsible for a substantial decline in the level of stock prices but which do not explain why the drop was so precipitous. Included in this category are the budget and trade deficits, increases in corporate and private debt and the general overvaluation of stocks in the face of rising interest rates. The second category, which might be called market mechanisms, offers more hope for explaining the unprecedented suddenness of the market’s move and the consequent dislocation of financial markets. Among these market mechanisms are portfolio insurance and other trading strategies, market making systems and index futures and options.” Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms, January 1988, U.S. Government Printing Office, page II-1.

10. Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms, January 1988.

11. Ibid. pp.29–42.

12. Shaaw, R.J., S. Chakraborty, and S. Balwani, “India’s NSE Says 59 Erroneous Orders Caused Stock Plunge.” Bloomberg News, October 6, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-10-05/nse-probing-freak-trade-that-caused-price-error-on-bourse.html.

13. Kisling, W., and I. King, “Rambus Trades Canceled by Exchanges on Error Rule.” Bloomberg News, January 4, 2010. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=awo2Jq9PcEMo.

14. Ibid.

15. Spicer, J., “High-Frequency Trading Firm Fined for Trading Malfunction.” Reuters News, November 25, 2011. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/25/cme-infinium-fine-idUSN1E7AO1C920111125?feedType=RSS&feedName=everything&virtualBrandChannel=11563.

16. Ibid.

17. Ruhle, S., C. Harper, and N. Mehta, “Knight Trading Loss Said to be Linked to Dormant Software.” http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-08-14/knight-software.html.

18. Valekevitch, C. and C. Mikolajczak, “Error by Knight Capital Rips Market.” Reuters News, August 1, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/08/01/us-usa-nyse-tradinghalts-idUSBRE8701BN20120801.

19. Massoudi, A., “Knight Capital Glitch Loss Hits $461m.” FT.com, October 17, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/928a1528-1859-11e2-80e9-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2Ca4yL47T

20. Ibid.

21. Demos, T., “BATS Pulls Its Own IPO Over ‘Technical Issues.’” Financial Times, March 24, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/073ae952-750c-11e1-90d1-00144feab49a.html#axzz2Ca4yL47T

22. Westfall, C., “BATS IPO: Accidental Death or Murder?” TheStreet.com. April 6, 2012. http://www.thestreet.com/story/11486165/1/bats-ipo-accidental-death-or-murder.html.

23. Massoudi, A. and A. Rappaport, “Nasdaq Suffers Fresh High-Profile Gaffe.” Financial Times, October 3, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/2f7d3b28-0d7c-11e2-bfcb-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2Ca4yL47T.

24. Massoudi, A., “Glitch Stops NYSE Trading in 216 Companies.” Financial Times, November 12, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/eb26489a-2d18-11e2-9211-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2Ca4yL47T.

25. Hume, N. and S-M. Ishmael, “Stock Exchange Meltdown Foils Eager Traders.” Financial Times, September 9, 2008. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/fadb3e0e-7e07-11dd-bdbd-000077b07658.html#axzz2Ca4yL47T

26. Silber, W., “What Happened to Liquidity When World War I Shut the NYSE?” Journal of Financial Economics, 2005, pp. 685–701.

27. Locke, P. and G.J. Kuserk, “The Chicago Loop Tunnel Flood: Cash Pricing and Activity.” Review of Futures Markets, 1993.

28. Hyuga, T., “UBS to Return Money from Tokyo Trading Error.” Bloomberg News, International Herald Tribune, Thursday, December 15, 2005.

29. Takafumi Horie was arrested for securities fraud by the Japanese authorities on January 23, 2006. He was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to prison.