Chapter 15. PCI Compliance for Merchants

Chapter Objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you will be able to do the following:

![]() Describe the PCI Data Security Standard framework.

Describe the PCI Data Security Standard framework.

![]() Recognize merchant responsibilities.

Recognize merchant responsibilities.

![]() Explain the 12 top-level requirements.

Explain the 12 top-level requirements.

![]() Understand the PCI DSS validation process.

Understand the PCI DSS validation process.

![]() Implement practices related to PCI compliance.

Implement practices related to PCI compliance.

Between 2008 and 2014, $127 billion dollars worth of credit, debit, and prepaid card transactions were processed. The sheer volume of transactions makes the payment card channel an attractive target for cybercriminals.

In order to protect cardholders against misuse of their personal information and to minimize payment card channel losses, the major payment card brands—Visa, MasterCard, Discover, JCB International, and American Express—formed the Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council and developed the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). On December 15, 2004, the Council released version 1.0 of the PCI DSS. Version 2.0 was released in October 2010 and version 3.0 was released in November 2013. The payment card brands can levy fines and penalties against organizations that do not comply with the requirements and/or revoke their authorization to accept payment cards.

In this chapter, we are going to examine the PCI DSS, version 3.0. Although designed for a specific constituency, the requirements can serve as a security blueprint for any organization.

Protecting Cardholder Data

To counter the potential for staggering losses, the payment card brands contractually require all organizations that store, process, or transmit cardholder data and/or sensitive authentication data comply with the PCI DSS. PCI DSS requirements apply to all system components where account data is stored, processed, or transmitted.

As shown in Table 15.1, account data consists of cardholder data plus sensitive authentication data. System components are defined as any network component, server, or application that is included in, or connected to, the cardholder data environment. The cardholder data environment is defined as the people, processes, and technology that handle cardholder data or sensitive authentication data.

Per the standards, the primary account number (PAN) must be stored in an unreadable (encrypted) format. Sensitive authentication data may never be stored post-authorization, even if encrypted.

The PAN is the defining factor in the applicability of PCI DSS requirements. PCI DSS requirements apply if the PAN is stored, processed, or transmitted. If the PAN is not stored, processed, or transmitted, PCI DSS requirements do not apply. If cardholder name, service code, and/or expiration date are stored, processed, or transmitted with the PAN, or are otherwise present in the cardholder data environment, they too must be protected.

Per the standards, the PAN must be stored in an unreadable (encrypted) format. Sensitive authentication data may never be stored post-authorization, even if encrypted.

Figure 15.1 shows the following elements located on the front of a credit card:

1. Embedded microchip. The microchip contains the same information as the magnetic stripe. Most non-U.S. cards have the microchip instead of the magnetic stripe. Some U.S. cards have both for international acceptance.

2. Primary account number (PAN).

3. Expiration date.

4. Cardholder name.

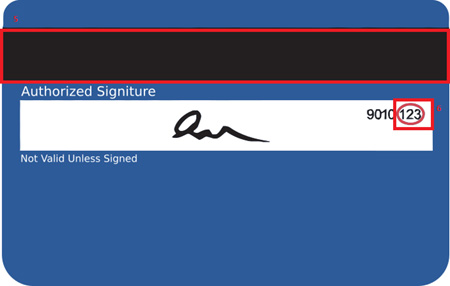

Figure 15.2 shows the following elements on the back of a credit card:

1. Magnetic stripe (mag stripe)—The magnetic stripe contains encoded data required to authenticate, authorize, and process transactions.

2. CAV2/CID/CVC2/CVV2—All refer to card security codes for the different payment brands.

Eliminating the collection and storage of unnecessary data, restricting cardholder data to as few locations as possible, and isolating the cardholder data environment from the rest of the corporate network is strongly recommended. Physically or logically segmenting the cardholder data environment reduces the PCI scope, which in turn reduces cost, complexity, and risk. Without segmentation, the entire network must be PCI compliant. This can be burdensome because the PCI-required controls may not be applicable to other parts of the network.

Utilizing a third party to store, process, and transmit cardholder data or manage system components does not relieve a covered entity of its PCI compliance obligation. Unless the third-party service provider can demonstrate or provide evidence of PCI compliance, the service provider environment is considered to be an extension of the covered entity’s cardholder data environment and is in scope.

What Is the PCI DDS Framework?

The PCI DSS framework includes stipulations regarding storage, transmission, and processing of payment card data, six core principles, required technical and operational security controls, testing requirements, and a certification process. Entities are required to validate their compliance. The number of transactions, the type of business, and the type of transactions determine specific validation requirements.

In today’s Internet-based environment, there are multiple points of access to cardholder data and varying technologies. Version 3.0 is designed to accommodate the various environments where cardholder data is processed, stored, or transmitted—such as e-commerce, mobile acceptance, or cloud computing. Version 3.0 also recognizes that security is a shared responsibility and addresses the obligations of each business partner in the transaction chain.

Business-as-Usual Approach

PCI DSS version 3.0 emphasizes that compliance is not a point-in-time determination but rather an ongoing process. Business-as-usual is defined as the inclusion of PCI controls as part of an overall risk-based security strategy that is managed and monitored by the organization. According to the PCI Standards Council, a business-as-usual approach “enables an entity to monitor the effectiveness of their security controls on an ongoing basis, and maintain their PCI DSS compliant environment in between PCI DSS assessments.” This means that organizations must monitor required controls to ensure they are operating effectively, respond quickly to control failures, incorporate PCI compliance impact assessments into the change-management process, and conduct periodic reviews to confirm that PCI requirements continue to be in place and that personnel are following secure processes.

Per the PCI Council, the version 3.0 updates are intended to do the following:

![]() Provide stronger focus on some of the greater risk areas in the threat environment.

Provide stronger focus on some of the greater risk areas in the threat environment.

![]() Build greater understanding of the intent of the requirements and how to apply them.

Build greater understanding of the intent of the requirements and how to apply them.

![]() Improve flexibility for all entities implementing, assessing, and building to the standards.

Improve flexibility for all entities implementing, assessing, and building to the standards.

![]() Help manage evolving risks/threats.

Help manage evolving risks/threats.

![]() Align with changes in industry best practices.

Align with changes in industry best practices.

![]() Eliminate redundant sub-requirements and consolidate policy documentation.

Eliminate redundant sub-requirements and consolidate policy documentation.

This approach mirrors best practices and reflects the reality that the majority of significant card breaches have occurred at organizations that were either self-certified or independently certified as PCI compliant.

What Are the PCI Requirements?

There are 12 top-level PCI requirements related to the six core principles. Within each requirement are sub-requirements and controls. The requirements are reflective of information security best practices. Quite often, the requirement’s title is misleading in that it sounds simple but the sub-requirements and associated control expectations are actually quite extensive. The intent of and, in some cases, specific details of the requirements are summarized in the following sections. As you read them, you will notice that they parallel the security practices and principles we have discussed throughout this text.

Build and Maintain a Secure Network and Systems

The first core principle—build and maintain a secure network and systems—includes the following two requirements:

1. Install and maintain a firewall configuration to protect cardholder data.

The basic objective of a firewall is ingress and egress filtering. The firewall does so by examining traffic and allowing or blocking transmissions based on a predefined rule set. The requirement extends beyond the need to have a firewall. It also addresses the following:

![]() Identifying and documenting all connections

Identifying and documenting all connections

![]() Designing a firewall architecture that protects cardholder data

Designing a firewall architecture that protects cardholder data

![]() Implementing consistent configuration standards

Implementing consistent configuration standards

![]() Documenting firewall configuration and rule sets

Documenting firewall configuration and rule sets

![]() Having a formal change management process

Having a formal change management process

![]() Requiring rule-set business justification

Requiring rule-set business justification

![]() Scheduling semiannual firewall rule-set review

Scheduling semiannual firewall rule-set review

![]() Implementing firewall security controls such as anti-spoofing mechanisms

Implementing firewall security controls such as anti-spoofing mechanisms

![]() Maintaining and monitoring firewall protection on mobile or employee-owned devices

Maintaining and monitoring firewall protection on mobile or employee-owned devices

![]() Publishing perimeter protection policies and related operational procedures

Publishing perimeter protection policies and related operational procedures

2. Do not use vendor-supplied defaults for system passwords and security parameters.

Although this seems obvious, there may be default accounts, especially service accounts, that aren’t evident or are overlooked. Additionally, systems or devices that are installed by third parties may be left at the default for ease of use. This requirement also extends far beyond its title and enters the realm of configuration management. Requirements include the following:

![]() Maintaining an inventory of systems and system components

Maintaining an inventory of systems and system components

![]() Changing vendor-supplied default passwords on all operating systems, applications, utilities, devices, and keys

Changing vendor-supplied default passwords on all operating systems, applications, utilities, devices, and keys

![]() Removing or disabling unnecessary default accounts, services, scripts, drivers, and protocols

Removing or disabling unnecessary default accounts, services, scripts, drivers, and protocols

![]() Developing consistent configuration standards for all system components that are in accordance with industry-accepted system-hardening standards (such as ISO and NIST)

Developing consistent configuration standards for all system components that are in accordance with industry-accepted system-hardening standards (such as ISO and NIST)

![]() Segregating system functions based on security levels

Segregating system functions based on security levels

![]() Using secure technologies (for example, SFTP instead of FTP)

Using secure technologies (for example, SFTP instead of FTP)

![]() Encrypting all non-console administrative access

Encrypting all non-console administrative access

![]() Publishing configuration management policies and related operational procedures

Publishing configuration management policies and related operational procedures

Protect Cardholder Data

The second core principle—Protect cardholder data—includes the following two requirements:

3. Protect stored card data.

This is a very broad requirement. As mentioned earlier, the cardholder data environment is defined as the people, processes, and technology that handle cardholder data or sensitive authentication data. Sited protection mechanisms include encryption, truncation, masking and hashing, secure disposal, and secure destruction. Requirements include the following:

![]() Data retention policies and practices that limit the retention of cardholder data and forbid storing sensitive authentication data post-authorization as well as card-verification code or value

Data retention policies and practices that limit the retention of cardholder data and forbid storing sensitive authentication data post-authorization as well as card-verification code or value

![]() Masking the PAN when displayed

Masking the PAN when displayed

![]() Rendering the PAN unreadable anywhere it is stored

Rendering the PAN unreadable anywhere it is stored

![]() Protecting and managing encryption keys (including generation, storage, access, renewal, and replacement)

Protecting and managing encryption keys (including generation, storage, access, renewal, and replacement)

![]() Publishing data-disposal policies and related operational procedures

Publishing data-disposal policies and related operational procedures

![]() Publishing data-handling standards that clearly delineate how cardholder data is to be handled

Publishing data-handling standards that clearly delineate how cardholder data is to be handled

![]() Training for all personnel that interact with or are responsible for securing cardholder data

Training for all personnel that interact with or are responsible for securing cardholder data

4. Encrypt transmission of cardholder data across open, public networks.

The objective here is to ensure that data in transit over public networks cannot be compromised and exploited. An open and/or public network is defined as the Internet, wireless technologies including Bluetooth, cellular technologies, radio transmission, and satellite communications. The requirements include the following:

![]() Using strong cryptography and security transmission protocols

Using strong cryptography and security transmission protocols

![]() Forbidding transmission of unprotected PANs by end-user messaging technologies such as email, chat, instant message, and text

Forbidding transmission of unprotected PANs by end-user messaging technologies such as email, chat, instant message, and text

![]() Publishing transmission security policies and related operational procedures

Publishing transmission security policies and related operational procedures

Maintain a Vulnerability Management Program

The third core principle—Maintain a vulnerability management program—includes the following two requirements:

5. Protect all systems against malware and regularly update antivirus software or programs.

As discussed in previous chapters, malware is a general term used to describe any kind of software or code specifically designed to exploit or disrupt a system or device, or the data it contains, without consent. Malware is one of the most vicious tools in the cybercriminal arsenal. The requirement includes:

![]() Selecting an antivirus/anti-malware solution commensurate with the level of protection required

Selecting an antivirus/anti-malware solution commensurate with the level of protection required

![]() Selecting an antivirus/anti-malware solution that has the capacity to perform periodic scans and generate audit logs

Selecting an antivirus/anti-malware solution that has the capacity to perform periodic scans and generate audit logs

![]() Deploying the antivirus/anti-malware solution on all applicable in-scope systems and devices

Deploying the antivirus/anti-malware solution on all applicable in-scope systems and devices

![]() Insuring that antivirus/anti-malware solutions are kept current

Insuring that antivirus/anti-malware solutions are kept current

![]() Insuring that antivirus/anti-malware solutions cannot be disabled or modified without management authorization

Insuring that antivirus/anti-malware solutions cannot be disabled or modified without management authorization

![]() Publishing anti-malware security policies and related operational procedures

Publishing anti-malware security policies and related operational procedures

![]() Training for all personnel on the implications of malware, disruption of the distribution channel, and incident reporting

Training for all personnel on the implications of malware, disruption of the distribution channel, and incident reporting

6. Develop and maintain secure systems and architecture.

This requirement mirrors the best practices guidance in Section 14 of ISO 27002:2013: Information Systems Acquisition, Development, and Maintenance, which focuses on the security requirements of information systems, applications, and code, from conception to destruction. The requirement includes the following:

![]() Keeping up-to-date on new vulnerabilities

Keeping up-to-date on new vulnerabilities

![]() Assessing the risk of new vulnerabilities

Assessing the risk of new vulnerabilities

![]() Maintaining a patch management process

Maintaining a patch management process

![]() Adhering to security principles and best practices throughout the systems development lifecycle (SDLC)

Adhering to security principles and best practices throughout the systems development lifecycle (SDLC)

![]() Maintaining a comprehensive change management process, including back-out and restore procedures

Maintaining a comprehensive change management process, including back-out and restore procedures

![]() Segregating the production environment from development, staging, and/or testing platforms

Segregating the production environment from development, staging, and/or testing platforms

![]() Adopting and internally publishing industry-accepted secure coding techniques (for example, OWASP)

Adopting and internally publishing industry-accepted secure coding techniques (for example, OWASP)

![]() Implementing code-testing procedures

Implementing code-testing procedures

![]() Training developers in secure coding and vulnerability management practices

Training developers in secure coding and vulnerability management practices

![]() Publishing secure coding policies and related operational procedures

Publishing secure coding policies and related operational procedures

Implement Strong Access Control Measures

The fourth core principle—Implement strong access control measures—includes the following three requirements:

7. Restrict access to cardholder data by business need-to-know.

This requirement reflects the security best practices of deny all, need-to-know, and least privilege. The objective is to ensure that only authorized users, systems, and processes have access to cardholder data. The requirement includes the following:

![]() Setting the default cardholder data access permissions to deny all

Setting the default cardholder data access permissions to deny all

![]() Identifying roles and system processes that need access to cardholder data

Identifying roles and system processes that need access to cardholder data

![]() Determining the minimum level of access needed

Determining the minimum level of access needed

![]() Assigning permissions based on roles, job classification, or function

Assigning permissions based on roles, job classification, or function

![]() Reviewing permissions on a scheduled basis

Reviewing permissions on a scheduled basis

![]() Publishing access control policies and related operational procedures

Publishing access control policies and related operational procedures

8. Identify and authenticate access to system components.

There are three primary objectives to this requirement. The first is to ensure that every user, system, and process is uniquely identified so that accountability is possible and to manage the account through its lifecycle. The second is to ensure that the strength of authentication credentials is commensurate with the access risk profile. The third is to secure the session from unauthorized access. This section is unique in that it sets specific implementation standards, including password length, password complexity, and session timeout. The requirement includes the following:

![]() Assigning and requiring the use of unique IDs for each account (user or system) and process that accesses cardholder data and/or is responsible for managing the systems that process, transmit, or store cardholder data.

Assigning and requiring the use of unique IDs for each account (user or system) and process that accesses cardholder data and/or is responsible for managing the systems that process, transmit, or store cardholder data.

![]() Implementing and maintaining a provisioning process that spans the account lifecycle from creation through termination. This includes access reviews and removing/disabling inactive user accounts at least every 90 days.

Implementing and maintaining a provisioning process that spans the account lifecycle from creation through termination. This includes access reviews and removing/disabling inactive user accounts at least every 90 days.

![]() Allowing single-factor authentication for internal access if passwords meet the following minimum criteria: seven alphanumeric characters, 90-day expiration, and no reuse of the last four passwords. Account lockout mechanism’s setting must lock out the user ID after six invalid login attempts and lock the account for a minimum of 30 minutes.

Allowing single-factor authentication for internal access if passwords meet the following minimum criteria: seven alphanumeric characters, 90-day expiration, and no reuse of the last four passwords. Account lockout mechanism’s setting must lock out the user ID after six invalid login attempts and lock the account for a minimum of 30 minutes.

![]() Requiring two-factor authentication for all remote network access sessions. Authentication mechanisms must be unique to each account.

Requiring two-factor authentication for all remote network access sessions. Authentication mechanisms must be unique to each account.

![]() Implementing session requirements, including a mandatory maximum 15-minute inactivity timeout that requires the user to reauthenticate, and monitoring remote vendor sessions.

Implementing session requirements, including a mandatory maximum 15-minute inactivity timeout that requires the user to reauthenticate, and monitoring remote vendor sessions.

![]() Restricting access to cardholder databases by type of account.

Restricting access to cardholder databases by type of account.

![]() Publishing authentication and session security policies and related operational procedures.

Publishing authentication and session security policies and related operational procedures.

![]() Training users on authentication-related best practices, including how to create and manage passwords.

Training users on authentication-related best practices, including how to create and manage passwords.

9. Restrict physical access to cardholder data.

This requirement is focused on restricting physical access to media (paper and electronic), devices, and transmission lines that store, process, or transmit cardholder data. The requirement includes the following:

![]() Implementing administrative, technical, and physical controls that restrict physical access to systems, devices, network jacks, and telecommunications lines within the scope of the cardholder environment.

Implementing administrative, technical, and physical controls that restrict physical access to systems, devices, network jacks, and telecommunications lines within the scope of the cardholder environment.

![]() Video monitoring physical access to sensitive areas, correlating with other entries, and maintaining evidence for a minimum of three months. The term sensitive areas refers to a data center, server room, or any area that houses systems that store, process, or transmit cardholder data. This excludes public-facing areas where only point-of-sale terminals are present, such as the cashier areas in a retail store.

Video monitoring physical access to sensitive areas, correlating with other entries, and maintaining evidence for a minimum of three months. The term sensitive areas refers to a data center, server room, or any area that houses systems that store, process, or transmit cardholder data. This excludes public-facing areas where only point-of-sale terminals are present, such as the cashier areas in a retail store.

![]() Having procedures to identify and account for visitors.

Having procedures to identify and account for visitors.

![]() Physically securing and maintaining control over the distribution and transport of any media that has cardholder data.

Physically securing and maintaining control over the distribution and transport of any media that has cardholder data.

![]() Securely and irretrievable destroying media (that has cardholder data) when it is no longer needed for business or legal reasons.

Securely and irretrievable destroying media (that has cardholder data) when it is no longer needed for business or legal reasons.

![]() Protecting devices that capture card data from tampering, skimming, or substitution.

Protecting devices that capture card data from tampering, skimming, or substitution.

![]() Training point-of-sale personnel about tampering techniques and how to report suspicious incidents.

Training point-of-sale personnel about tampering techniques and how to report suspicious incidents.

![]() Publishing physical security policies and related procedures.

Publishing physical security policies and related procedures.

Regularly Monitor and Test Networks

The fifth core principle—Regularly monitor and test networks—includes the following two requirements:

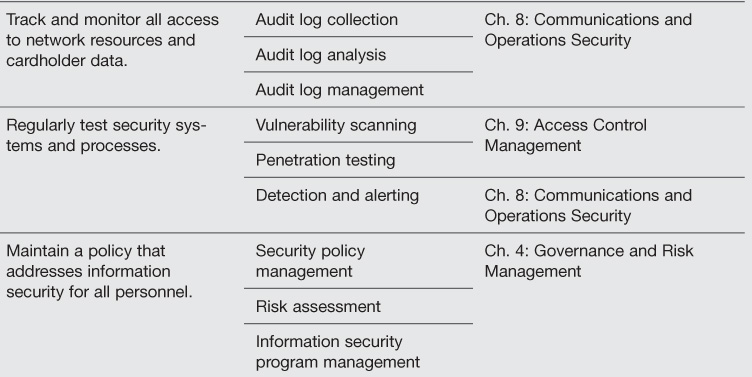

10. Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data.

The nucleus of this requirement is the ability to log and analyze card data–related activity, with the dual objective of identifying precursors and indicators of compromise, and the availability of corroborative data if there is a suspicion of compromise. The requirement includes the following:

![]() Logging of all access to and activity related to cardholder data, systems, and supporting infrastructure. Logs must identity the user, type of event, date, time, status (success or failure), origin, and affected data or resource.

Logging of all access to and activity related to cardholder data, systems, and supporting infrastructure. Logs must identity the user, type of event, date, time, status (success or failure), origin, and affected data or resource.

![]() Logging of user, administrator, and system account creation, modifications, and deletions.

Logging of user, administrator, and system account creation, modifications, and deletions.

![]() Ensuring the date and time stamps are accurate and synchronized across all audit logs.

Ensuring the date and time stamps are accurate and synchronized across all audit logs.

![]() Securing audit logs so they cannot be deleted or modified.

Securing audit logs so they cannot be deleted or modified.

![]() Limiting access to audit logs to individuals with a need to know.

Limiting access to audit logs to individuals with a need to know.

![]() Analyzing audit logs in order to identify anomalies or suspicious activity.

Analyzing audit logs in order to identify anomalies or suspicious activity.

![]() Retaining audit logs for at least one year, with a minimum of three months immediately available for analysis.

Retaining audit logs for at least one year, with a minimum of three months immediately available for analysis.

![]() Publishing audit log and monitoring policies and related operational procedures.

Publishing audit log and monitoring policies and related operational procedures.

11. Regularly test security systems and processes.

Applications and configuration vulnerabilities are identified on a daily basis. Ongoing vulnerability scans, penetration testing, and intrusion monitoring are necessary to detect vulnerabilities inherent in legacy systems and/or have been introduced by changes in the cardholder environment. The requirement to test security systems and processes is specific in how often testing must be conducted. This requirement includes the following:

![]() Implementing processes to detect and identify authorized and unauthorized wireless access points on a quarterly basis.

Implementing processes to detect and identify authorized and unauthorized wireless access points on a quarterly basis.

![]() Running internal and external network vulnerability scans at least quarterly and whenever there is a significant change in the environment. External scans must be performed by a PCI Approved Scanning Vendor (ASV).

Running internal and external network vulnerability scans at least quarterly and whenever there is a significant change in the environment. External scans must be performed by a PCI Approved Scanning Vendor (ASV).

![]() Resolving all “high-risk” issues identified by the vulnerability scans. Verifying resolution by rescanning.

Resolving all “high-risk” issues identified by the vulnerability scans. Verifying resolution by rescanning.

![]() Performing annual network and application layer external and internal penetration tests using an industry-accepted testing approach and methodology (for example, NIST SP 800-115, OWASP). If issues are identified, they must be corrected and the testing redone to verify the correction.

Performing annual network and application layer external and internal penetration tests using an industry-accepted testing approach and methodology (for example, NIST SP 800-115, OWASP). If issues are identified, they must be corrected and the testing redone to verify the correction.

![]() Using intrusion detection (IDS) or intrusion prevention (IPS) techniques to detect or prevent intrusions into the network.

Using intrusion detection (IDS) or intrusion prevention (IPS) techniques to detect or prevent intrusions into the network.

![]() Deploying a change detection mechanism to alert personnel to unauthorized modifications of critical system files, configuration files, and content files.

Deploying a change detection mechanism to alert personnel to unauthorized modifications of critical system files, configuration files, and content files.

![]() Publishing security testing policies and related operational procedures.

Publishing security testing policies and related operational procedures.

Maintain an Information Security Policy

The sixth core principle—Maintain an information security policy—includes the final requirement:

12. Maintain a policy that addresses information security for all personnel.

Of all the requirements, this may be the most inaptly named. A more appropriate title would be “Maintain a comprehensive information security program (including whatever we’ve forgotten to include in the first 11 requirements).” This requirement includes the following:

![]() Establishing, publishing, maintaining, and disseminating an information security policy. The policy should include but not be limited to the areas noted in the other 11 PCI DSS requirements. The policy should be authorized by executive management or an equivalent body.

Establishing, publishing, maintaining, and disseminating an information security policy. The policy should include but not be limited to the areas noted in the other 11 PCI DSS requirements. The policy should be authorized by executive management or an equivalent body.

![]() Annually reviewing, updating, and reauthorizing the information security policy.

Annually reviewing, updating, and reauthorizing the information security policy.

![]() Implementing a risk assessment process that is based on an industry-accepted approach and methodology (for example, NIST 800-30, ISO 27005).

Implementing a risk assessment process that is based on an industry-accepted approach and methodology (for example, NIST 800-30, ISO 27005).

![]() Assigning responsibility for the information security program to a designated individual or team.

Assigning responsibility for the information security program to a designated individual or team.

![]() Implementing a formal security awareness program.

Implementing a formal security awareness program.

![]() Educating personnel upon hire and then at least annually.

Educating personnel upon hire and then at least annually.

![]() Requiring users to annually acknowledge that they have read and understand security policies and procedures.

Requiring users to annually acknowledge that they have read and understand security policies and procedures.

![]() Performing thorough background checks prior to hiring personnel who may be given access to cardholder data.

Performing thorough background checks prior to hiring personnel who may be given access to cardholder data.

![]() Maintaining a vendor management program applicable to service providers with whom cardholder data is shared or who could affect the security of cardholder data.

Maintaining a vendor management program applicable to service providers with whom cardholder data is shared or who could affect the security of cardholder data.

![]() Requiring service providers to acknowledge in a written agreement their responsibility in protecting cardholder data.

Requiring service providers to acknowledge in a written agreement their responsibility in protecting cardholder data.

![]() Establishing and practicing incident response capabilities.

Establishing and practicing incident response capabilities.

![]() Establishing and practicing disaster response and recovery capabilities.

Establishing and practicing disaster response and recovery capabilities.

![]() Establishing and practicing business continuity capabilities.

Establishing and practicing business continuity capabilities.

![]() Annually testing incident response, disaster recovery, and business continuity plans and procedures.

Annually testing incident response, disaster recovery, and business continuity plans and procedures.

PCI Compliance

Complying with the PCI standards is a contractual obligation that applies to all entities involved in the payment card channel, including merchants, processors, financial institutions, and service providers, as well as all other entities that store, process, or transmit cardholder data and/or sensitive authentication data. The number of transactions, the type of business, and the type of transactions determine specific compliance requirements.

It is important to emphasize that PCI compliance is not a government regulation or law. The requirement to be PCI compliant is mandated by the payment card brands in order to accept card payments and/or be a part of the payment system. PCI standards augment but do not supersede legislative or regulatory requirements to protect personally identifiable information (PII) or other data elements.

Who Is Required to Comply with PCI DSS?

Merchants are required to comply with the PCI DSS. Traditionally a merchant is defined as a seller. It is important to note that the PCI DSS definition is a departure from the traditional definition. For the purposes of the PCI DSS, a merchant is defined as any entity that accepts American Express, Discover, JCB, MasterCard, or Visa payment cards as payment for goods and/or services (including donations). The definition does not use the terms store, seller, and retail; instead, the focus is on the payment side rather than the transaction type. Effectively, any company, organization, or individual that accepts card payments is a merchant. The mechanism for collecting data can be as varied as an iPhone-attached card reader, a parking meter, a point-of-sale checkout, or even an offline system.

Compliance Validation Categories

PCI compliance validation is composed of four levels, which are based on the number of transactions processed per year and whether those transactions are performed from a physical location or over the Internet. Each payment card brand has the option of modifying its requirements and definitions of PCI compliance validation levels. Given the dominance of the Visa brand, the Visa categorization is the one most often applicable. The Visa brand parameters for determining compliance validation levels are as follows. Any entity that has suffered a breach that resulted in an account data compromise may be escalated to a higher level.

![]() A Level 1 merchant meets one of the following criteria:

A Level 1 merchant meets one of the following criteria:

![]() Processes over six million Visa payment card transactions annually (all channels).

Processes over six million Visa payment card transactions annually (all channels).

![]() A merchant that has been identified by any card association as a Level 1 merchant.

A merchant that has been identified by any card association as a Level 1 merchant.

![]() Any merchant that Visa, at its sole discretion, determines should meet the Level 1 requirements to minimize risk to the Visa system.

Any merchant that Visa, at its sole discretion, determines should meet the Level 1 requirements to minimize risk to the Visa system.

![]() A Level 2 entity is defined as any merchant—regardless of acceptance channel—processing one million to six million Visa transactions per year.

A Level 2 entity is defined as any merchant—regardless of acceptance channel—processing one million to six million Visa transactions per year.

![]() A Level 3 merchant is defined as any merchant processing 20,000 to 1,000,000 Visa e-commerce transactions per year.

A Level 3 merchant is defined as any merchant processing 20,000 to 1,000,000 Visa e-commerce transactions per year.

![]() A Level 4 merchant is defined as any merchant processing fewer than 20,000 Visa e-commerce transactions per year, and all other merchants—regardless of acceptance channel—processing up to one million Visa transactions per year.

A Level 4 merchant is defined as any merchant processing fewer than 20,000 Visa e-commerce transactions per year, and all other merchants—regardless of acceptance channel—processing up to one million Visa transactions per year.

An annual onsite compliance assessment is required for Level 1 merchants. Level 2 and Level 3 merchants may submit a self-assessment questionnaire (SAQ). Compliance validation requirements for Level 4 merchants are set by the merchant bank. Submission of an SAQ is generally recommended but not required. All entities with externally facing IP addresses must engage an ASV to perform quarterly external vulnerability scans.

What Is a Data Security Compliance Assessment?

A compliance assessment is an annual onsite evaluation of compliance with the PCI DSS conducted by either a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) or an Internal Security Assessor (ISA). The assessment methodology includes observation of system settings, processes, and actions, documentation reviews, interviews, and sampling. The culmination of the assessment is a Report on Compliance (ROC).

Assessment Process

The assessment process begins with documenting the PCI DSS cardholder environment and confirming the scope of the assessment. Generally, a QSA/ISA will initially conduct a GAP assessment to identify areas of noncompliance and provide remediation recommendations. Post-remediation, the QSA/ISA will conduct the assessment. In order to complete the process, the following must be submitted to either the acquiring financial institution or payment card brand:

![]() ROC completed by a QSA or ISA

ROC completed by a QSA or ISA

![]() Evidence of passing vulnerability scans by an ASV

Evidence of passing vulnerability scans by an ASV

![]() Completion of the Attestation of Compliance by the assessed entity and the QSA

Completion of the Attestation of Compliance by the assessed entity and the QSA

![]() Supporting documentation

Supporting documentation

Report on Compliance

As defined in the PCI DSS Requirements and Security Assessment Procedures, the ROC standard template includes the following sections:

![]() Section 1: Executive Summary

Section 1: Executive Summary

![]() Section 2: Description of Scope of Work and Approach Taken

Section 2: Description of Scope of Work and Approach Taken

![]() Section 3: Details about Reviewed Environment

Section 3: Details about Reviewed Environment

![]() Section 4: Contact Information and Report Date

Section 4: Contact Information and Report Date

![]() Section 5: Quarterly Scan Results

Section 5: Quarterly Scan Results

![]() Section 6: Findings and Observations

Section 6: Findings and Observations

![]() Compensating Controls Worksheets (if applicable)

Compensating Controls Worksheets (if applicable)

Sections 1–5 provide a detailed overview of the assessed environment and establish the framework for the assessor’s findings. The ROC template includes specific testing procedures for each PCI DSS requirement.

Section 6, “Findings and Observations,” contains the assessor’s findings for each requirement and testing procedure of the PCI DSS as well as information that supports and justifies each finding. The information provided in “Findings and Observations” summarizes how the testing procedures were performed and the findings achieved. This section includes all 12 PCI DSS requirements.

What Is the SAQ?

The SAQ is a validation tool for merchants that are not required to submit to an onsite data security assessment. There are two parts to the SAQ: the controls questionnaire and a self-certified attestation. Per the June 2012 PCI DSS SAQ Instructions and Guidelines, there are five SAQ categories. The categories and number of questions per assessment described next are based on PCI DSS V2 (as of November 2012, V3 SAQs were not yet available). The number of questions vary because the questionnaires are designed to be reflective of the specific payment card channel and the anticipated scope of the cardholder environment.

![]() SAQ A (13 questions) is applicable to merchants who retain only paper reports or receipts with cardholder data, do not store cardholder data in electronic format, and do not process or transmit any cardholder data on their systems or premises. This would never apply to face-to-face merchants.

SAQ A (13 questions) is applicable to merchants who retain only paper reports or receipts with cardholder data, do not store cardholder data in electronic format, and do not process or transmit any cardholder data on their systems or premises. This would never apply to face-to-face merchants.

![]() SAQ P2PE (18 questions) is applicable to merchants who process cardholder data only via payment terminals included in a validated and PCI SSC–listed Point-to-Point Encryption (P2PE) solution. This would never apply to e-commerce merchants. This category was added in June 2012.

SAQ P2PE (18 questions) is applicable to merchants who process cardholder data only via payment terminals included in a validated and PCI SSC–listed Point-to-Point Encryption (P2PE) solution. This would never apply to e-commerce merchants. This category was added in June 2012.

![]() SAQ B (29 questions) is applicable to merchants who process cardholder data only via imprint machines or standalone, dial-out terminals. This would never apply to e-commerce merchants.

SAQ B (29 questions) is applicable to merchants who process cardholder data only via imprint machines or standalone, dial-out terminals. This would never apply to e-commerce merchants.

![]() SAQ C-VT (51 questions) is applicable to merchants who process cardholder data only via isolated virtual terminals on personal computers connected to the Internet. This would never apply to e-commerce merchants.

SAQ C-VT (51 questions) is applicable to merchants who process cardholder data only via isolated virtual terminals on personal computers connected to the Internet. This would never apply to e-commerce merchants.

![]() SAQ C (80 questions) is applicable to merchants whose payment application systems are connected to the Internet either because the payment application system is on a personal computer that is connected to the Internet (for example, for email or web browsing) or the payment application system is connected to the Internet to transmit cardholder data.

SAQ C (80 questions) is applicable to merchants whose payment application systems are connected to the Internet either because the payment application system is on a personal computer that is connected to the Internet (for example, for email or web browsing) or the payment application system is connected to the Internet to transmit cardholder data.

![]() SAQ D (288 questions) is applicable to all other merchants not included in descriptions for SAQ types A through C as well as all service providers defined by a payment brand as eligible to complete an SAQ.

SAQ D (288 questions) is applicable to all other merchants not included in descriptions for SAQ types A through C as well as all service providers defined by a payment brand as eligible to complete an SAQ.

Completing the SAQ

In order to achieve compliance in question, the response to each question must either be “yes” or an explanation of a compensating control. Compensating controls are allowed when an organization cannot implement a specification but has sufficiently addressed the intent using an alternate method. If an entity cannot provide affirmative responses, it is still required to submit an SAQ.

To complete the validation process, the entity submits the SAQ and an accompanying Attestation of Compliance stating that it is or is not compliant with the PCI DSS. If the attestation indicates noncompliance, a target date for compliance along with an action plan needs to be provided. The attestation must be signed by an executive officer.

Are There Penalties for Noncompliance?

There are three types of fines: PCI noncompliance, Account Data Compromise Recovery (ADCR) for compromised domestic-issued cards, and Data Compromise Recovery Solution (DCRS) for compromised international-issued cards. Noncompliance penalties are discretionary and can vary greatly, depending on the circumstances. They are not openly discussed or publicized.

Fines and Penalties

More financially significant than PCI noncompliance fines, a data compromise could result in ADCR and/or DCRS penalties. Due to the structure of the payment system, if there is a merchant compromise, the payment brands impose the penalties on the bank that issued the account. The banks pass all liability downstream to the entity. The fines may be up to $500,000 per incident. In addition, the entity may be liable for the following:

![]() All fraud losses perpetrated using the account numbers associated with the compromise (from date of compromise forward)

All fraud losses perpetrated using the account numbers associated with the compromise (from date of compromise forward)

![]() Cost of reissuance of cards associated with the compromise (approximately $50 per card)

Cost of reissuance of cards associated with the compromise (approximately $50 per card)

![]() Any additional fraud prevention/detection costs incurred by credit card issuers associated with the compromise (that is, additional monitoring of system for fraudulent activity)

Any additional fraud prevention/detection costs incurred by credit card issuers associated with the compromise (that is, additional monitoring of system for fraudulent activity)

![]() Increased transaction fees

Increased transaction fees

At their discretion, the brands may designate any size compromised merchants as Level 1, which requires an annual onsite compliance assessment. Acquiring banks may choose to terminate the relationship.

Alternately, the payment brands may waive fines in the event of a data compromise if there is no evidence of noncompliance with PCI DSS and brand rules. According to Visa, “to prevent fines, a merchant must maintain full compliance at all times, including at the time of breach as demonstrated during a forensic investigation. Additionally, a merchant must demonstrate that prior to the compromise, the compromised entity had already met the compliance validation requirements, demonstrating full compliance.” This is an impossibly high standard to meet. In reality, uniformly when there has been a breach, the brands have declared the merchant to be noncompliant.

Summary

The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, known as PCI DSS, applies to all entities involved in the payment card channel, including merchants, processors, financial institutions, and service providers, as well as all other entities that store, process, or transmit cardholder data and/or sensitive authentication data. The PCI DSS framework includes stipulations regarding storage, transmission, and processing of payment card data, six core principles, 12 categories of required technical and operational security controls, testing requirements, and a validation and certification process. Entities are required to validate their compliance. The number of transactions, the type of business, and the type of transactions determine specific validation requirements.

Compliance with PCI DSS is a payment card channel contractual obligation. It is not a government regulation or law. The requirement to be PCI compliant is mandated by the payment card brands in order to accept card payments and/or be part of the payment system. PCI standards augment but do not supersede legislative or regulatory requirements to protect PII or other data elements.

Overall, the PCI DSS requirements are reflective of information security best practices. Version 3.0 introduced a risk model designed to allow entities to respond quickly to emerging criminal threats to the payment channel.

Test Your Skills

Multiple Choice Questions

1. The majority of payment card fraud is borne by __________.

A. consumers

B. banks, merchants, and card processors

C. Visa and MasterCard

D. All of the above

2. Which of the following statements best describes the objective of the PCI Security Standards Council?

A. The objective of the PCI Security Standards Council is to create a single enforcement body.

B. The objective of the PCI Security Standards Council is to create a common penalty structure.

C. The objective of the PCI Security Standards Council is to create a single payment card security standard.

D. The objective of the PCI Security Standards Council is to consolidate all payment card rules and regulations.

3. A skimmer can be used to read ____________.

A. the cardholder data

B. sensitive authentication data

C. the associated PIN

D. All of the above

4. According to PCI DDS, which of the following is true of the primary account number (PAN)?

A. It must never be stored.

B. It can only be stored in an unreadable (encrypted) format.

C. It should be indexed.

D. It can be stored in plain text.

5. Which of the following statements best describes sensitive authentication data?

A. Sensitive authentication data must never be stored, ever.

B. Sensitive authentication data can be stored indefinitely in an unreadable (encrypted) format.

C. Sensitive authentication data should be masked.

D. Sensitive authentication data may never be stored post-authorization.

6. Which of the following tasks is the PCI Security Standards Council not responsible for?

A. Creating a standard framework

B. Certifying ASVs and QSAs

C. Providing training and educational materials

D. Enforcing PCI compliance

7. Which of the following statements best describes PCI DSS Version 3?

A. PCI DSS Version 3 is a departure from earlier versions because the core principles have changed.

B. PCI DSS Version 3 is a departure from earlier versions because it promotes a risk-based approach.

C. PC I DSS Version 3 is a departure from earlier versions because the penalties have increased.

D. PC I DSS Version 3 is a departure from earlier versions because it shifts the compliance obligation to service providers.

8. Which of the following statements best describes the “cardholder data environment”?

A. The “cardholder data environment” includes the people that handle cardholder data or sensitive authentication data.

B. The “cardholder data environment” includes the processes that handle cardholder data or sensitive authentication data.

C. The “cardholder data environment” includes the technology that handles cardholder data or sensitive authentication data.

D. All of the above.

9. Sensitive authentication data does not include which of the following?

A. PINs

B. Card expiration date

C. CVV2

D. Mag stripe or chip data

10. Which of the following statements best describes the PAN?

A. If the PAN is not stored, processed, or transmitted, then PCI DSS requirements do not apply.

B. If the PAN is not stored, processed, or transmitted, then PCI DSS requirements apply only to e-commerce merchants.

C. If the PAN is not stored, processed, or transmitted, then PCI DSS requirements apply only to Level 1 merchants.

D. None of the above.

11. Which of the following statements is true?

A. When a debit or ATM card is lost or stolen, the cardholder liability is limited to $50.

B. When a debit or ATM card is lost or stolen, the cardholder is responsible for all charges.

C. When a debit or ATM card is lost or stolen, the cardholder liability depends on when the loss or theft is reported.

D. When a debit or ATM card is lost or stolen, the cardholder is never responsible for the charges.

12. The terms CVV2, CID, CVC2, and CVV2 all refer to the ___________.

A. authentication data

B. security code

C. expiration date

D. account number

13. There are 12 categories of PCI standards. In order to be considered compliant, an entity must comply with or document compensating controls for _________.

A. All of the requirements

B. 90% of the requirements

C. 80% of the requirements

D. 70% of the requirements

14. Which of the following is not considered a basic firewall function?

A. Ingress filtering

B. Packet encryption

C. Egress filtering

D. Perimeter protection

15. Which of the following is considered a secure transmission technology?

A. FTP

B. HTTP

C. Telnet

D. SFTP

16. Which of the following statements best describes key management?

A. Key management refers to the generation, storage, and protection of encryption keys.

B. Key management refers to the generation, storage, and protection of server room keys.

C. Key management refers to the generation, storage, and protection of access control list keys.

D. Key management refers to the generation, storage, and protection of card manufacturing keys.

17. Which of the following methods is an acceptable manner in which a merchant can transmit a PAN?

A. Using cellular texting

B. Using an HTTPS/SSL session

C. Using instant messaging

D. Using email

18. Which of the following statements is true?

A. The PCI requirement to protect all systems against malware requires that merchants select a malware solution commensurate with the level of protection required.

B. The PCI requirement to protect all systems against malware requires that merchants select a PCI-certified anti-malware solution.

C. The PCI requirement to protect all systems against malware requires that merchants select a PCI-compliant anti-malware solution.

D. The PCI requirement to protect all systems against malware requires that merchants select a malware solution that can be disabled if necessary.

19. Which of the following documents lists injection flaws, broken authentication, and cross-site scripting as the top three application security flaws?

A. ISACA Top Ten

B. NIST Top Ten

C. OWASP Top Ten

D. ISO Top Ten

20. Which of the following security principles is best described as the assigning of the minimum required permissions?

A. Need-to-know

B. Deny all

C. Least privilege

D. Separation of duties

21. Which of the following is an example of two-factor authentication?

A. Username and password

B. Password and challenge question

C. Username and token

D. Token and PIN

22. Skimmers can be installed and used to read cardholder data enter at ________.

A. point-of-sale systems

B. ATMs

C. gas pumps

D. All of the above

23. Which of the following best describes log data?

A. Log data can be used to identify indicators of compromise.

B. Log data can be used to identify primary account numbers.

C. Log data can be used to identify sensitive authentication data.

D. Log data can be used to identify cardholder location.

24. Quarterly external network scans must be performed by a __________.

A. managed service provider

B. Authorized Scanning Vendor

C. Qualified Security Assessor

D. independent third party

25. In keeping with the best practices set forth by the PCI standard, how often should information security policies be reviewed, updated, and authorized?

A. Once

B. Semi-annually

C. Annually

D. Bi-annually

26. Which of the following is true of PCI requirements?

A. PCI requirements augment regulatory requirements.

B. PCI requirements supersede regulatory requirements.

C. PCI requirements invalidate regulatory requirements.

D. None of the above.

27. The difference between a Level 1 merchant and Levels 2–4 merchants is that ______________________________________________.

A. Level 1 merchants must have 100% compliance with PCI standards.

B. Level 1 merchants must complete an annual onsite compliance assessment.

C. Level 1 merchants must have quarterly external vulnerabilities scans.

D. Level 1 merchants must complete a self-assessment questionnaire.

28. Which of the following statements is true of entities that experience a cardholder data breach?

A. They must pay a minimum $50,000 fine.

B. They may be reassigned as a Level 1 merchant.

C. They will no longer be permitted to process credit cards.

D. They must report the breach to a federal regulatory agency.

29. Which of the following statements best describes the reason different versions of the SAQ are necessary?

A. The number of questions vary by payment card channel and scope of environment.

B. The number of questions vary by geographic location.

C. The number of questions vary by card brand.

D. The number of questions vary by dollar value of transactions.

30. Which of the following statements is true of an entity that determines it is not compliant?

A. The entity does not need to submit an SAQ.

B. The entity should notify customers.

C. The entity should submit an action plan along with its SAQ.

D. The entity should do nothing.

Exercises

Exercise 15.1: Understanding PCI DSS Obligations

1. Compliance with PCI DSS is a contractual obligation. Explain how this differs from a regulatory obligation.

2. Which takes precedence—a regulatory requirement or a contractual obligation? Explain your answer.

3. Who enforces PCI compliance? How is it enforced?

Exercise 15.2: Understanding Cardholder Liabilities

1. What should a consumer do if he or she misplaces a debit card? Why?

2. Go online to your bank’s website. Does it post instructions on how to report a lost or stolen debit or credit card? If yes, summarize their instructions. If no, call the bank and request the information be sent to you. (If you don’t have a bank account, choose a local financial institution.)

3. Explain the difference between the Fair Credit Billing Act (FCBA) and the Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA).

Exercise 15.3: Choosing an Authorized Scanning Vendor

1. PCI security scans are required for all merchants and service providers with Internet-facing IP addresses. Go online and locate three PCI Council Authorized Scanning Vendors (ASV) that offer quarterly PCI security scans.

2. Read their service descriptions. What are the similarities and differences?

3. Recommend one of the ASVs. Explain your reasoning.

Exercise 15.4: Understanding PIN and Chip Technologies

1. Payment cards issued in the United States store sensitive authentication information in the magnetic stripe. What are the issues associated with this configuration?

2. Payment cards issued in Europe store sensitive authentication information in an embedded microchip. What is the advantage of this configuration?

3. Certain U.S. financial institutions will provide a chip-embedded card upon request. Identify at least one card issuer who will do so. Does it charge extra for the card?

Exercise 15.5: Identifying Merchant Compliance Validation Requirements

Complete the following table:

Projects

Project 15.1: Applying Encryption Standards

Encryption is referenced a number of times in the PCI DSS standard. For each of the PCI requirements listed below:

1. Explain the rationale for the requirement.

2. Identify a encryption technology that can be used to satisfy the requirement.

3. Identify a commercial application that can be used to satisfy the requirement.

![]() PCI DSS V3. 3.4.1—If disk encryption is used, logical access must be managed separately and independently of native operating system authentication and access control mechanisms (for example, by not using local user account databases or general network login credentials).

PCI DSS V3. 3.4.1—If disk encryption is used, logical access must be managed separately and independently of native operating system authentication and access control mechanisms (for example, by not using local user account databases or general network login credentials).

![]() PCI DSS V3. 4.1—Use strong cryptography and security protocols to safeguard sensitive cardholder data during transmission over open, public networks.

PCI DSS V3. 4.1—Use strong cryptography and security protocols to safeguard sensitive cardholder data during transmission over open, public networks.

![]() PCI DSS V3. 4.1.1—Ensure wireless networks transmitting cardholder data or connected to the cardholder data environment, and use industry best practices to implement strong encryption for authentication and transmission.

PCI DSS V3. 4.1.1—Ensure wireless networks transmitting cardholder data or connected to the cardholder data environment, and use industry best practices to implement strong encryption for authentication and transmission.

Project 15.2: Completing an SAQ

All Level 2 and Level 3 merchants and some Level 4 merchants are required to submit a Self-Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ). Access the Official PCI Security Standards Council website and download SAQ A and SAQ C.

1. What are the differences and similarities between SAQ A and C? Describe the merchant environment for each SAQ.

2. Explain how the scope of a cardholder environment impacts the completion of SAQ C. Give two specific examples where narrowing the scope would be beneficial.

3. Read the SAQ C compensating controls section. Explain what is meant by compensating controls and give two specific examples.

Project 15.3: Reporting an Incident

Assume you are a Level 2 merchant and your organization suspects a breach of Visa cardholder information.

1. Go to http://usa.visa.com/merchants/risk_management/cisp_if_compromised.html. Document the steps you should take.

2. Does your state have a breach notification law? If so, would you be required to report this type of breach to a state authority? Would you be required to notify customers? What would you need to do if you had customers who lived in a neighboring state?

3. Have there been any major card breaches within the last 12 months that affected residents of your state? Summarize such an event.

References

“Cash Dying as Credit Card Payments Predicted to Grow in Volume,” Huffington Post, June 6, 2012, accessed 10/2013, www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/06/07/credit-card-payments-growth_n_1575417.html.

“2013 Data Breach Investigations Report,” Verizon, accessed 11/2013, www.verizonenterprise.com/DBIR/2013.

“Data Security—PCI Mandatory Compliance Programs,” Wells Fargo, accessed 11/2013, www.wellfargo.com/biz/merchant/service/manage/risk/security.

“Debit and Credit Card Skimming,” Privacy Sense, accessed 11/2013, www.privacysense.net/debit-and-credit-card-skimming/.

“Genesco, Inc. v. VISA U.S.A., Inc., VISA Inc., and VISA International Service Association,” United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee, Nashville Division. Filed March 7, 2013, Case 3:13-cv-00202.

“Global Payments Breach Tab: $94 Million,” Bank InfoSecurity, accessed 11/2013, www.bankinfosecurity.com/global-payments-breach-tab-94-million-a-5415/op-1.

Green, Joe. “Credit card ‘skimming’ a real danger, Secret Service officials warn,” South NJ Times, accessed 11/2013, www.nj.com/gloucester-county/index.ssf/2013/10/creditdebit_card_skimming_a_real_danger_south_jersey_secret_service_officials_warn.html.

“Global Payments Sec 10-Q Filing,” Investor Relations, accessed 11/2013, http://investors.globalpaymentsinc.com/financials.cfm.

Krebs, Brian. “All about Skimmers,” accessed 11/2013, http://krebsonsecurity.com/all-about-skimmers/.

“Lost or Stolen Cred, ATM and Debit Cards,” Federal Trade Commission Consumer Information, accessed 11/2013, www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/0213-lost-or-stolen-credit-atm-and-debit-cards.

“Merchant PCI DSS Compliance,” Visa, accessed 11/2013, http://usa.visa.com/merchants/risk_management/cisp_merchants.html.

“Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, Navigating PCI DSS, Understanding the Intent of the Requirements, Version 2.0,” PCI Security Standards Council, LLC, October 2010.

“Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, PCI DSS Quick Reference Guide, Understanding the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, Version 2.0,” PCI Security Standards Council LLC, October 2010.

“Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, ROC Reporting Instructions for PCI DSS 2.0,” PCI Security Standards Council, LLC, September 2011.

“Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, Self-Assessment Questionnaire Instructions and Guidelines, Version 2.1,” PCI Security Standards Council, LLC, June 2012.

“Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard and Payment Application Data Security Standard, Version 3.0: Change Highlights,” PCI Security Standards Council, LLC, August 2013.

“Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, Requirements and Security Assessment Procedures, Version 3.0,” PCI Security Standards Council, LLC, November 2013.

“Plastic, Please! The Dominance of Card Payments,” True Merchant, accessed 10/2013, www.truemerchant.com/plastic-please-the-dominance-of-card-payments/.

“Processor Global Payments Prepares to Close the Book on Its Data Breach,” Digital Transactions, accessed 11/2013, http://digitaltransactions.net/news/story/3940.

United States of America v. Kevin Konstantinov and Elvin Alisuretove, United States District Court for the Eastern District of Oklahoma. Filed July 9, 2013, Case CR13-062-RAW.

United States of America v. Drinkman, Kalinin, Kotov, Rytikov, Smilianets, United States District Court, District of New Jersey, Indictment case number 09-626(JBS) (8-2).