10. Feedback, Recognition, and Reward

“I can live for two months on a good compliment!”

—Mark Twain

The previous chapters have focused on the satisfactions and dissatisfactions that are intrinsic to the work itself. We turn now to external sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction. We are referring to that sense of achievement and accomplishment that comes from the opinions of others, especially the opinions of those whose views we respect or can influence our careers and earnings. Feedback from others also enables us to improve how we do our work and so obtain an even greater sense of achievement.

Do Workers Get the Feedback They Need?

The majority of employees (86 percent) in our surveys say that they know what is expected of them. However, only 63 percent claim to receive sufficient feedback on how well they do their work, and 64 percent say they receive recognition for a job well done. Most interestingly, only 37 percent of surveyed workers disagree with the statement, “I get criticized much more quickly for poor performance than praised for good performance,” which means that the performance of many employees is more likely to be “recognized” in a negative sense: when it is deemed subpar more often than when it meets or exceeds a manager’s expectations. The following comments, which respond to the question, “What do you like least about working here?” exemplify that data:

Having to deal on a daily basis with my manager since every time he gives feedback, it is always negative. That is the only thing I think in the mornings when going to work. Am I going to get more of his negative feedback? I leave my house with a negative feeling, drive to work with a negative feeling. When I finally get here, my motivation is sapped.

I will never, never, never—I repeat never—hear anything good from my supervisor about my work. It’s as if praising an employee somehow lessens him. He simply has to be the only one who matters here. But make a mistake and he’s on your back immediately.

My manager is a pretty good guy and certainly knows his job but has to learn that you don’t only give feedback to an employee when something goes wrong. He praises very, very rarely.

We are told that some people are entirely “inner-directed.” They don’t care about the opinions of others, and they don’t need external impetus or feedback to be productively engaged in their work. Where these people are, we don’t know! Wouldn’t it be terrific if all of us were so “inner-directed” that others’ reactions to our work were irrelevant? Unfortunately, that is not human nature. Aside from the usefulness of feedback in providing direction to employees and helping them improve, human beings require some degree of attention and appreciation from others to perform at their best levels. When that performance is taken for granted by management, as in, “That’s what we expect; why mention it?,” employees and the company lose.

Considered most broadly, performance feedback is a vehicle for the following:

• Guidance. The steps an employee can take to improve his performance.

• Evaluation. How the organization regards the employee’s performance in relation to expectations and to others. Is the employee doing well, poorly, or average?

• Recognition. Expressing appreciation for a job well done.

• Reward. Recognition translated into something tangible (usually money).

• Direction. Communicating or reinforcing what the organization needs, values, and expects from employees.

These five aspects and outcomes of feedback are vital to employees and the organization. Although most people have a sense of responsibility and want to do their jobs well, that motivation can wane rapidly if no one seems to care. On the other hand, if no one seems to care except when something goes wrong, motivation can quickly turn into resentment.

Let’s take a thorough look at each of these functions of feedback.

Guidance

Guidance refers to the cognitive functions of feedback. It is the process of providing employees with empirical, objective information about their performance and how to improve it. This is not the same as affective feedback, which relates to evaluation, recognition, and reward. In real life, of course, cognitive and affective feedback are not so easily separated: it is difficult to communicate the errors a person makes without also conveying an evaluation of her performance. That is one of the major problems in providing the kind of feedback that employees accept and use rather than resist. We will return to this problem shortly, including suggestions as to how to deal with it.

At its most basic level, nobody can function in life (much less at work) without factual feedback. We do something and want to know whether what we did had the expected or desired effect. The source of feedback does not have to be human: we learn whether we combed our hair to our liking from a mirror; whether we’re speeding from a speedometer; whether we get to work on time from a clock; whether we’re exercising too hard from a heart monitor. Feedback allows us to modify our behavior; for example, we can decide to take a faster method of transportation when late for an appointment, and the next time we have the same appointment, we can decide to leave home earlier.

Critical to us as humans is feedback from other humans. Some feedback requires human intervention to give it real meaning, such as a doctor interpreting the results of a medical test for a patient. Some feedback can only be from other humans, like much of the feedback people get on the appropriateness of their behavior in daily life (whether, for example, their behavior conforms to basic civility and good manners).

At work, the most crucial feedback people can receive concerns their performance. Without feedback, there can be only a limited sense of achievement and opportunity to improve performance. Almost all organizations have numerous performance measures: profitability, sales, costs, delivery time, customer defections, productivity, defective parts, absenteeism, and the like. Ideally, the measures are designed into the business or work process so that they are provided automatically and frequently—sometimes continuously—to the organization and its employees.

Even the most comprehensive and most automatic measurement systems almost invariably require human intervention. By themselves, numbers have limited meaning within organizations. What matters is how management and employees interpret those numbers. How do the numbers, for example, stack up against management’s expectations? Are the changes observed in the measures—improvements or decrements—considered significant by the organization? Do other events, such as the introduction of new equipment or a change in general economic conditions, account for variations in the measures? How do the measures compare to each other (say, an increase in quality accompanied by a decrease in productivity), and what is the significance of that comparison? In general, what is the relative importance of the various measures? (They are rarely of equal importance.)

The answers to these questions are vital to making sense of the numbers and to enable both the organization and the employee to decide on a proper course of action. If, for example, the productivity of an employee declines soon after the introduction of new equipment but declines less than what was expected, it is likely that no action would be required of that employee and management might even reward him in some way. If, on the other hand, an employee’s performance improves but is less than what’s expected (say, months after the use of the new equipment has been fully integrated into the employee’s work), that could signal the need for corrective action. The action might include greater clarity in what is expected from the employee or additional coaching on using the new equipment.

Both the employee who performs well and the employee whose performance is below expectations need feedback, not just from the “numbers,” but from a manager capable of interpreting the numbers and conveying their meaning. Part of what is also being conveyed to the employee is, of course, direction: what really matters to management in the employee’s performance and behavior. (We return to that function of feedback later in this chapter.)

Giving performance feedback is easier said than done. Many managers consider it among their most difficult tasks. Here is a comment about giving performance reviews from a manager’s perspective:

The annual performance reviews I am required to conduct with my 12 direct reports is the one thing I hate about this job. I always put it off until I’m called by the HR Department and forced to do it. My employees often can’t take the criticism... they argue with me. They say they’re surprised at what I said and all they want to know is about the size of their salary increase. I try to make them as brief as possible, get them over with as soon as possible. Sure, I slant them toward the positive. Who needs the trouble? Yes, I’ll put in something that “needs improvement” so I won’t be bothered by my boss or HR; it’s just a game. By the way, I haven’t ever been appraised by my manager, who is the VP of Manufacturing, since I can’t remember when. He hates to do it, too, but HR won’t get after him about it.

This comment is not atypical: by and large, managers dislike (a few even dread) giving performance appraisals; they want to get them over with as quickly as possible and with as little trouble as possible. Some managers claim that it is a problem of time and onerous paperwork, ranking up there with organizing file cabinets.

The problem, however, is not confined to the formal performance appraisal. Providing informal day-to-day feedback throughout the year can also be difficult for managers. Comments such as this one are often heard:

I would like to hear from my manager now and then. You know, informally about how he feels I’m doing—might be with a few tips on how I can improve and might be a compliment from time to time. But we only speak about my performance at my annual performance appraisal, when I’m often surprised about what he likes and doesn’t like about my performance. The only time I hear from him other than appraisal time is the rare occasion I have screwed up royally. He reads me the riot act and I probably deserve it, but it always takes me by surprise. When appraisal time rolls around, I expect the worst. It usually goes okay, but I’m always nervous before we sit down and go through my appraisal numbers.

A Short Course on Giving Cognitive Feedback

Performance feedback is done less frequently than it should be, and when it is done, it may be poorly handled. It does not have to be so. A large amount of research has been done on the conditions that make for effective feedback.1 From these studies, specific guidelines for managers have emerged. Adhering to these makes performance feedback less onerous for managers and more helpful to employees. Here are the key guidelines.

1. Do Not Equate Performance Feedback with the Annual Performance Appraisal

Managers often make this big mistake. Aside from the fact that many such appraisals tend to be somewhat perfunctory and, to avoid unpleasantness, are positively biased, reserving feedback for that time—even when it is comprehensive and unbiased—violates a basic principle of learning and change: namely, that feedback should be given as closely in time as possible to the actual situation. If an employee is performing unsatisfactorily in some way, it should be obvious that he needs to know about it then and there so that the behavior does not continue. (This is also true of recognition and the reinforcement of good performance; we discuss that later in this chapter.) Many of the difficulties encountered during performance appraisal sessions come from employees being surprised by what they hear.

The extent to which employees learn something entirely new about their performance during the appraisal review is a measure of the failure of the performance-review process. The purposes of an annual review are to summarize, in the form of ratings and commentary, the employee’s performance over the year; to more fully discuss that performance and the effectiveness of the improvement steps the employee has undertaken to improve (including what the manager can do to help the employee); to discuss the implications of the performance for salary increases and other rewards; and to put in place plans for the next year, such as setting the employee’s performance goals.

The formal annual appraisal session, then, is a mechanism for closure on one year and for planning the next. Also, it provides time away from immediate job pressures to simply talk about topics of relevance to the employee and his manager. In many organizations, this is a rare opportunity for a conversation that is more than perfunctory. Managers should be required to do it, and do it with the attitude and tools that these guidelines suggest.

2. Don’t Assume That Employees Are Only Interested in Receiving Praise for What They Do Well and Resent Having Areas in Need of Improvement Pointed Out to Them

People enjoy being praised and prefer praise to criticism, but it is a myth that they have no interest in learning what they don’t do well and what they must do to improve. This is not a hypothetical statement or wishful thinking. Take a look at some common types of write-in comments:

I love my supervisor. He is one of the best managers I have had since I have been here. He encourages us to do well and keeps us well informed of what we need to do, and he gives us feedback in a calm, helpful way when we do something wrong. I find what he says very helpful and I listen very carefully.

My manager assists me with an actionable plan for my current job, things I can do better, as well as my career/professional development. He provides avenues for growth and development. In fact, his manager and he make up a great management team. It’s a real education working for them.

My supervisor is...fair and willing to listen to our feedback, but she also doesn’t hold back when she feels something needs improvement. She readily tries to find solutions to any and all situations or problems and is more than willing to join us in resolving issues. I feel fortunate to have her as my supervisor. She is a good manager and friend.

For the last three months, my team has a new...leader who is dedicated and honest and provides us with all the information we need to measure our success. Before, I was never given any [feedback during the year]; I was always told by my previous supervisor my job was great. The big surprise was at the end of the year when I was given what I considered a marginal rating. There were obviously improvement opportunities nobody ever made me aware of. Thank heavens this will not happen with my current team leader.

It should not be a surprise that employees really do want feedback. Employees naturally want to know how they can do their jobs better because improvement will give them a greater sense of achievement and pride. Why, then, do managers so often assume the opposite and hesitate to point out to employees opportunities for improvement?

One reason is that a few employees are extremely thin-skinned and find even a hint of criticism intolerable. They might even see criticism where none exists, exhibiting a bit of paranoia. Such employees are difficult to deal with in this respect, but, fortunately, they comprise just a tiny percentage of any workforce. As with the small numbers of people “allergic to work” discussed earlier, do not generalize to everybody else based on just a few employees. Although many employees do seem to resist feedback and be overly sensitive to criticism, that is not primarily because of employees’ psychological problems, but rather is a result of the way managers handle feedback.2

A second reason, therefore, for managers’ hesitation in providing feedback is that many managers simply do not know how to discuss needed improvements in their employees’ work without irritating or discouraging them. So they tend to avoid it entirely or deal with it through vague and indirect communications, or, most commonly, oscillate between saying little or nothing and, when that is no longer possible (as in “the last straw”), overreact in a harsh way that surprises and angers employees.

Of course, some managers neither hold back nor oscillate in their criticism; they are the managers who don’t much care what employees think, and they can be unrelenting in finding fault with the performance of their employees. These managers are inclined to believe that workers don’t want to work (or are careless or stupid) and that their performance will always be deficient unless they are continually reminded of what they are doing wrong and the consequences of not improving. Interestingly, we find this management style to be as common—perhaps even more so—in the way managers treat other managers who report to them (especially in the treatment meted out by high-level executives) as in the way non-managerial employees are treated by their managers. In some companies, managers are subject by their bosses to much verbal abuse, including humiliation in front of their peers. After all, senior management argues, isn’t “being able to take it” one of the reasons managers are paid a high salary? “If they can’t stand the heat, they should get out of the kitchen.” How do these people actually react to that kind of treatment? Here are just three examples from managers:

My manager treats all his direct reports equally, that is, without respect and dignity. He’s like a tyrant who only gives feedback when he is unhappy with something. He rants and raves, and doesn’t do this in the privacy of his office. He doesn’t care who is around, even the people who work for me.

There is a total lack of respect and a general condescending attitude by our management. This is a daily and constant reminder of managerial incompetence and the lack of direction in which this establishment is headed. What is preached, respect, is blatantly not practiced. I and my colleagues don’t behave that way with our employees. How did these upper-level managers get where they are?

He [the CEO] treats the workers with kid gloves, he’s like their father. With us, he’s usually a first-class [expletive deleted]. He even blasts us for doing something he asked us to do because he changed his mind. Nobody dares answer back or question him; he’s the king.

Whatever the pattern, managers may not have good role models when it comes to giving feedback. As they observe employees’ and their own reactions to the process, their belief is reinforced that performance feedback can be a difficult and unenviable job. But we know that there are managers who are good at it: they don’t procrastinate in getting it done, and they get the performance results they want with little distress for themselves or their employees. It comes down to a matter of skill (to be discussed in detail later in this chapter) and to the fundamental assumptions that managers make about people at work. Do managers assume that their employees want to do the best job possible and would appreciate management’s observations and guidance about their performance? Or do they believe that employees don’t care about doing a good job and so have to be bludgeoned into doing any work at all or doing the work correctly? Or do they believe that employees care about doing good work so much and their egos are so fragile that pointing out any performance problems would be considered a mortal wound?

Our view is that besides a small minority of employees (those “allergic” to work and those inordinately sensitive to criticism), the first assumption is valid: employees want to perform well and learn how they can improve. If a manager operates on the basis of that assumption, he will succeed, provided he follows a few basic guidelines, such as those we spell out here. But, without accepting that basic premise, these guidelines become meaningless.

To summarize, feedback needs to proceed from a manager’s intentions to help and guide his employees. The goal should be learning, not venting, shaming, or lambasting.

3. An Employee Whose Overall Performance Is Satisfactory and Appreciated by the Organization Needs to Be Made Aware of That

In the course of an employee doing his job, the work is usually satisfactory, and even outstanding at times, but occasionally it will not be good enough. That pattern is true of the overwhelming majority in every organization, and it is vital that an employee understands that management sees his performance that way. In other words, most everyone is good, but nobody’s perfect, and it is to the employee’s and organization’s benefit that striving for improvement be continual and normal. (We discuss later on the case of poor performers who should never have been hired into their jobs or into the organization.)

We have seen that many employees agree with the statement, “A person here gets criticized much more quickly for poor performance than praised for good performance.” That management style makes people uneasy about management’s view of their overall performance and contribution to the organization. It is then difficult for an employee to feel anything but insecurity and resentment when criticized on any aspect of his performance, no matter how valid and needed the criticism is and how small the object of criticism is relative to the employee’s total performance.

It is easier for employees to accept the need for improvement—in fact, many welcome it—when they believe that management basically likes what they do and is helping them do it even better. Believing that their contribution is genuinely appreciated requires more than being told from time to time in general terms, “We are happy with your work here.” To be accepted as genuine, general comments and evaluations require a factual basis that is achieved by recognition of specific accomplishments, such as, “That report you wrote is great. I especially liked the part where you....”

Being specific in your praise diminishes the feeling that the praise is given for effect (a sort of public-relations gesture) and is helpful in pointing out the areas of performance that the employee needs to maintain. This brings us to the importance of specificity in dealing with improvement opportunities.

4. Comments About Areas That Need Improvement Should Be Specific and Factual Rather Than Evaluative, and Directed at the Situation Rather Than the Person

Positive feedback and feedback about improvement needs are similar in that both require the manager to be as specific and factual as possible. Although comments on positive aspects of performance should, indeed, convey a positive evaluation, it is better to avoid a negative tone when pointing out a need for improvement.

It is helpful to say, “You did a good job on this,” but it is not helpful to say, “You did a poor job on this.” Instead, you might say, “Here is something that I think needs to be done differently.” Terms such as “good,” “great,” “excellent,” and “first class,” especially when accompanied by the specifics that support those evaluations, build pride in employees and reinforce the performance so that it is sustained. But is there any point to saying to an otherwise satisfactorily performing employee that she did a “poor,” “shoddy,” “unprofessional,” or “below standard” job on something? She already knows that a problem exists because a manager has told her and is being specific about the problem. Adding an evaluative comment is likely to discourage or offend the employee and, in the long run, diminish her motivation and performance.

It gets worse when the negative evaluative comment is directed at the person rather than the person’s performance. This is seen most commonly in critical comments about the supposed disposition or intention of the employee, such as, “You must not have been paying attention when you did that,” “You must find it difficult to change and do it a different way,” or even, “You must have gotten up on the wrong side of the bed this morning.” Although the manager might feel he is being helpful with these remarks, the employee views them as attacks on his character and reacts with defensiveness. Furthermore, managers are not being paid or asked by the organization or their employees to be psychologists. Engaging in amateur psychology is often a power-play anyway (it says, “I can see into you”), and employees feel that and resent it. To summarize, stick to what the employee does rather than what he is.

There are exceptions to the recommendation to avoid negative evaluations of the employee’s performance. First, the formal performance appraisal is a time when the manager needs to rate the employee on various dimensions of performance, and these might not be favorable: “You did well on this aspect of your performance, but not on this.” Obviously, we all would like to receive positive rather than negative performance evaluations, but because the formal appraisal sums up the year and can be the basis for rewards such as salary increases, the manager can’t, in our view, escape that responsibility. Furthermore, employees expect and want to know how their performance over the course of the year stacks up in management’s eyes. The negative effects of unfavorable ratings are greatly mitigated if, as per our guidelines, the evaluations have a factual basis and are unsurprising because they are, indeed, a summary of the feedback the employee received throughout the year.

The second exception to the recommendation regarding unfavorable evaluations is the case of the truly unsatisfactory employee; he has to know and must know early. (We discuss this situation later in this chapter.)

5. Feedback Needs to Be Limited to Those Aspects of Employee Behavior That Relate to Performance

In their performance feedback, some managers dwell on aspects of employee behavior that are personally objectionable to the manager but are unrelated, or only marginally related, to the employee’s performance or to the organization’s success. These aspects might be completely outside the work situation, such as the way the employee spends her leisure time, gets along with her spouse, or raises her children. On the job, some managers are overly concerned and critical about employees’ dress, even when it is wholly within the bounds of appropriate work attire. One employee complained bitterly in an interview about his manager’s dislike of his southern accent.

Indeed, many aspects of what an employee does on the job or the way he lives are truly none of the manager’s business or are trivial and reflect little more than a manager’s personal preferences and prejudices. Some managers see themselves as parental figures who provide “helpful” guidance to employees about all things, whether it’s wanted or not, whether it’s related to job performance or not, and whether it’s important or not. The manager must try to stick to the job and those factors that significantly affect job results. Advice on other matters should be given only when the employee seeks it (assuming the manager has knowledge in those areas).

6. When Giving Performance Feedback, Encourage Two-Way Communication

When giving feedback, it is almost always sensible to involve the employee in determining what the problem is and what to do about it. Obviously, this isn’t wise when the employee is so new on the job that asking his opinion adds no value. It also shouldn’t be done those few times when the manager is absolutely certain she knows what needs to be done and just wants the employee to do it. Engaging the employee in a participative conversation then—other than to clarify what the manager wants—is likely to be seen as manipulative by the employee. Other than those occasions, the manager needs to ask the employee what he thinks and should genuinely listen to him. After all, the employee is on the job, and his experience and observations must be taken into account to determine how a performance problem is to be overcome, including what the manager might be doing to harm the employee’s performance. A real conversation also makes the employee more of a “partner” in the improvement process rather than simply a target of criticism. It helps create an atmosphere in which the employee feels comfortable initiating questions of his manager that will help him improve his work.

7. Remember That the Goal of Feedback Is Action That Improves Performance

This guideline is obvious, but it is violated in a number of ways. The first example is when the manager assumes that the issue is the employee’s will or character, in which case he simply admonishes the employee to, “Pay attention to what you’re doing!,” or “Get moving, we need more from you!,” or “Stop talking with everyone!” Those comments are appropriate for only a few workers, the ones for whom insufficient motivation is indeed the problem. However, they are unhelpful to the great majority of employees and convey disrespect for them. What is needed is a specific, doable action plan that attacks the problem, not the person, as is shown in the following example (which is fictionalized from actual events):

Manager: I’d like to talk to you about meeting deadlines for reports that my boss asked you to prepare. I think you missed a couple of deadlines recently.

Employee: I didn’t realize these requests had specific deadlines. He just dropped by my desk and, in a low-key manner, asked me to obtain some information.

Manager: That’s his style. Please remember to translate any request he makes as urgent. I had the same problem early in my career. You might want to ask him when he wants this. He’s likely to say as soon as possible. This usually means he wants you to start on it right away and have it to him in a day or two. I realize this puts you in a difficult situation. Feel free to come to me when he makes his next request.

A second way this rule is violated is to require action that is not in the immediate control of the person to whom the feedback is given. Remember that the action must be doable; making it so might require resources outside of the employee’s immediate control. Here’s an example of a manager really “going to bat” for her employee. This is what you want to see happen (and read in your company survey):

My leader is... open and honest, and I am able to be the same with her. She is always available to assist me and goes out of her way to assist with my development. For example, I didn’t understand the new system changes well enough. She not only provided me some materials to read and forwarded the relevant training courses available, but also put me in touch with an expert to call whenever I had a problem. I don’t think I would still be here if it wasn’t for her.

The third major way in which this rule is violated is when an employee is so overwhelmed with identified problems and action steps that he simply does nothing or does things in a superficial way. A good rule of thumb is to have the employee work on no more than two or three significant action items at any time. Arriving at these requires prioritization, which is governed by what is most doable and what has the most impact on performance.

8. Follow Up and Reinforce

For most action steps following feedback, the manager needs to follow up with the employee to assess progress: whether action has been taken, what the results were, and what, if anything, still needs to be done. Follow-up also gives the manager an opportunity to compliment the employee on the changes made, which positively reinforces the behavior. Furthermore, the act of following up—and the employee knowing that it will occur—emphasizes to the employee the importance of taking action.

9. Provide Feedback Only in Areas in Which You Are Competent

We leave the most obvious guideline for last: know what you are talking about. Our guidelines, as focused as they have been on how feedback should be conveyed, cannot substitute for inaccuracies and gaps in what is conveyed to an employee. Only under duress will employees pay attention to feedback from managers who know little or nothing about the workers’ jobs. We see this problem frequently when the organization hires recent college graduates into supervisory jobs. These new supervisors find themselves managing workers who have been on those jobs for years and who, in many respects, are more knowledgeable than their managers. We often see comments such as this from frustrated workers:

This company must stop hiring these young hotshots into front-line supervisory positions just because they have college diplomas. They come on the job and tell us what to do, but they know diddly squat. They think they can learn the job in a day or a week, but it takes years to know what’s really going on with the machinery, by working with those who really know what’s what. In the old days, the foremen rose through the ranks. We respected them because they knew the job at least as well as we did.

Be modest and honest about what you know, and get the right kind of help for the worker. When we discuss advancement later in this chapter, we question the wisdom of most of the hiring that is done directly into managerial positions.

We conclude our discussion of cognitive feedback with a brief mention of a technique increasingly being used—namely, “360” feedback. Thus far, our focus has been primarily on feedback from managers to employees. Through the 360 process, ratings on various aspects of performance are gathered from a variety of sources in addition to the manager, especially subordinates (if the employee is a manager), peers, and internal and external customers (hence “360” for 360 degrees, or feedback from a number of angles). 360 feedback is valuable precisely because it provides data from multiple sources and perspectives. (Other terms for the technique are multi-source and multi-rater feedback.) A manager may be personally biased in his evaluations of employees, but even if not biased may be unaware of crucial aspects of employees’ behavior, such as the way they interact with their peers. There is quite a bit of research data supporting the effectiveness of 360 feedback in changing behavior, particularly when the process is facilitated and supported by follow-up counseling.3

Evaluation, Recognition, and Reward

We come now to the affective or evaluative side of feedback, which is the manager’s and the organization’s judgment of how well the employee is doing and what the implications are of that judgment.

In our previous discussion of cognitive feedback, it was impossible to ignore entirely the affective side. Although it is desirable to avoid evaluative comments when the feedback concerns improvement needs, we don’t want to separate facts from evaluation when the employee does something well. In that case, evaluation and facts are inseparable because nothing needs to change in the employee’s performance, so there’s no reason for any feedback other than to praise and thank the employee for a job well done.

How important is employee recognition for generating enthusiasm and maintaining good performance? On the surface, it might not seem to be terribly important. From the organization’s perspective, isn’t the company already paying the employee for good performance? But providing such recognition is vital: receiving recognition for one’s achievements is among the most fundamental of human needs, from early in life—think of young children eagerly awaiting their parents’ praise for their accomplishments in school—to and through adulthood, even though it may not be as visible then. Just as parents do well by their children when they express admiration for their children’s “work,” so do managers when they praise their employees’ contributions. In our interviews and the write-in questions on our surveys, workers tell us with deep feeling how much they appreciate a compliment.

When managers do not bother to acknowledge high levels of employee performance, the effect is discouraging to most employees and devastating to some.

The desire for recognition of one’s achievements is neither childish nor neurotic. Freud, the pre-eminent student of both childhood and neuroses (and the relationship between the two), is said to have quipped at his 80th birthday party that, “An individual can tolerate infinite helpings of praise.” We sometimes hear people deny that recognition is important to them; a worker might say “forget the praise; just give me the money,” but their behavior belies this assertion. We did a study once at a media organization in which a tough chief executive scoffed at high-priced employees craving professional recognition. However, those employees reported that when the CEO was passed over for a prestigious industry award, there was much fulminating and stomping around his office.

Of course, the desire for recognition can also be extreme and dysfunctional. We see this in some people in the way their need for praise is insatiable: they require it continuously, often for achievements not particularly noteworthy, and become depressed or agitated when it is not forthcoming. Furthermore, they are not too discriminating about the sources of the recognition: they want it from everyone, from people they respect and from those they disdain, from those with power and from those with no influence over their careers. Often, they are the employees we see vying for the spotlight and grabbing credit for achievements that are either not theirs or not solely theirs. They tend to be noisy and visible (often whiny), but as with the other needs we have discussed, this extreme constitutes a tiny percentage of the workforce.

Psychologically healthy people want to be recognized for their genuine achievements and are concerned primarily with the opinions of those whom they admire and, because they are realistic, with the opinions of those who can help or hurt their careers.

Before continuing this discussion, let’s reiterate the difference between recognition for performance and respectful treatment of workers (the latter was the subject of Chapter 6, “Respect.”) As we use the term, respect is a matter of equity that’s owed to employees simply by virtue of their employment, just as they are owed a living wage as long as they are employed. Respect, in other words, is a function of who they are—employees and human beings. On the other hand, recognition is for what they do: how they are performing for and contributing to the organization. Respect and recognition are not entirely independent, of course. The term recognition has two meanings: to acknowledge someone’s performance, and to acknowledge someone’s existence. The latter is a mark of respect in the workplace, such as managers being sure to say hello to employees and referring to them by name. That is important to a worker but is not the kind of recognition that is the subject of this chapter. For recognition, the parallel comment is, “Thank you!” Whether, how much, and how a worker is thanked varies with the worker’s performance. That differs from respect, which dictates that everyone deserves a hello. The importance of recognition is evident in the panoply of awards (both financial and nonfinancial) dispensed by public, private, and nonprofit organizations throughout America and, indeed, the world. The range is enormous, from Nobel Prizes, Oscars, and building and street names for the famous (or soon-to-be famous) to company pins, plaques, gold watches, and various cash awards for the obscure (and now less obscure). These are the formal means of recognition, and organizations understand that they meet deeply felt needs. Unfortunately, these formal means might be administered in a way that severely dilutes their impact or even boomerangs to the detriment of the employees and the organization. It is also unfortunate that when executives think of employee recognition in their organizations, they usually equate that with formal recognition programs and give not nearly as much attention to informal recognition, such as managers acknowledging good performance day-to-day on the shop or office floor. Or, they equate recognition with the compensation system—pay, pay increases, bonuses, stock awards, and so on. In that view, recognition programs, if they exist, are seen as “icing on the cake”—nice to have, but not really at the heart of what employees want, which is money.

What Makes for Effective Recognition of Workers?

There are four major means to recognize employees. No one vehicle, such as money, suffices to provide the recognition to employees that is most important to them and beneficial for the organization:

• Compensation. Providing differential compensation to employees based on their performance.

• Informal recognition. Day-to-day recognition of performance, most importantly by the immediate manager.

• Honorifics. Special awards given as part of formal awards programs and that may be accompanied by cash for an employee’s performance.

• Promotion. Advancement to higher-level positions for performance.

First, we will consider compensation, informal recognition, and honorifics, all of which involve just the current job of the employee and require no criteria for their exercise other than performance. We will then discuss the role of advancement to higher-level jobs.

Management can use compensation, informal recognition, and honorifics to recognize employees either individually or in groups. The three methods are independent of each other in certain respects and interdependent in other ways. They are independent because each is important in its own right and cannot be substituted for each other. In previous chapters, we took strong exception to the view that satisfaction with the work itself can be substituted for money, and the corollary proposition that when workers complain about pay, they are really complaining about unsatisfying work. We argued that workers want both (and more), and to neglect either will significantly diminish employee satisfaction and motivation.

Similarly, we take issue with those who argue that only money serves to give workers genuine recognition, or, at the opposite extreme, that all they “really” crave is “attention” or “esteem” (and that a focus on money is a displacement brought on by their frustration in not getting what they really want). And so, some suggest that the basic human need to feel appreciated can be satisfied by recognition programs and no-cost job-recognition devices.4 This advice might comfort managements trying to economize, but it is unhelpful—and even dangerous—because it ignores money’s importance to people and can cause managers to believe that they can manipulate and “psychologize” people and save on labor costs. They can’t—not for long, anyway. It doesn’t matter that part of the power of money is its symbolic or psychological significance. Whether symbolic or practical, it is of great importance to most people and cannot be satisfied with nonfinancial rewards.

Psychological rewards are not a substitute for money, but managers should not make the opposite error, which is believing that money can be a substitute for psychological recognition. Both are important. For example, a high-level executive in an investment bank told one of the authors, in the late 1980s, about an experience he had with the bank’s chairman. It was the end of the year and bonuses were being distributed. The chairman came into the executive’s office, gave him an envelope with his bonus check, and said, “This is for you,” and walked out. The check was for $500,000. The executive was discouraged and angry. “Why didn’t he say anything to me?” he asked. “I have no idea what he really thinks of my performance and whether he cares whether I stay or leave. He never tells me.”

This sounds nutty. Shouldn’t $500,000 be enough? Doesn’t the amount of money speak for itself? No, it doesn’t. It is terribly important that employees also hear from their management directly and personally that their performance is appreciated. Employees in that company describe the chairman as keeping employees on a “slippery slope,” perpetually anxious about his evaluation of them. When he meets employees in the hallways, he almost invariably “greets” them by mentioning something that hasn’t gone well in their area of responsibility or something they haven’t done. The chairman has a difficult time expressing appreciation to others, even when giving them large bonuses; that, of course, would be an ideal time to do so. The executive left the company about six months later because, as he put it in a private conversation, it was “an opportunity I couldn’t refuse,” and “I could no longer take [chairman’s name].”

The needs for both money and nonfinancial rewards are important. Neither can replace the other. There are also, however, two senses in which they are interdependent. First, they are multiplicative—not just additive—in their effects. Put negatively, if one form of recognition is absent, not only is the total effect reduced, it is reduced by more than would be expected simply by its absence. This is because it also diminishes the impact of the other form of recognition. We saw this clearly in the previous example in which not getting a “thank you” reduced the positive impact of a substantial bonus. By the same logic, adding one form of recognition to another increases the value of the latter. Consider honorifics, which are the formal awards programs of organizations. The lesson of our argument for those programs is that their impact on employees is usually increased when money accompanies them. As in the investment bank case, adding words of appreciation to the bonus would have increased its value for the executive, so adding money to an award conveys to an employee that the organization really means it because it is putting its money where its mouth is. To be most effective, then, most formal awards programs require both mouth and money. Although the money involved is no substitute for basic kinds of compensation (salary increases, bonuses, and so on), it should be substantial enough to be seen as more than just a token.

Our argument does not, of course, imply that day-to-day informal recognition be accompanied by money. But what is said informally loses its impact if it is not reflected at the appropriate time in the employee’s compensation.

The three means of recognition are also interdependent in that they need to be consistent with each other in the criteria used for recognition. For example, if a company has embarked on a quality improvement effort—at least in its public statements—it is likely to use its formal awards programs to recognize employees for quality contributions and to do so in a public way. In day-to-day informal communications and recognition and in compensation (such as pay increases), the message might be different: if it is then really quantity that counts, the messages are inconsistent and counterproductive. It’s the kind of contradiction that creates confusion among employees as to what management wants and skepticism about management’s integrity; those severely compromise the impact of an organization’s recognition efforts. The criteria must be aligned, and this should be achieved by aligning each with the organization’s real goals and values. In that way, employees are rewarded, and the goals of the organization are advanced and its values reinforced.

To be most effective, therefore, organizations must think of recognition as a cluster of components integrated with each other and with the organization’s goals and values.

How is recognition best implemented? There are a number of basic principles here, some of which we touched on earlier:

• Be specific about what is being recognized. The employee needs to be praised for concrete achievements. This both reinforces the particular behaviors that the manager wants to see repeated and, in the eyes of the employee, increases the credibility of the praise.

• Do it in person. Although this might sound obvious, recognition by long distance or proxy is not nearly as effective as face-to-face recognition.

• Be timely. Give recognition as soon as possible after the desired behavior. By and large, the greater the interval between the completion of a behavior and the delivery of a reinforcing consequence, the less effective is the reinforcement. This advice is wonderfully summarized in the phrase “catch them at being good.” Catching people in the act, as it were, is usually reserved for misdeeds, but applying the same principle to good performance is exactly what managers should do.

The guidance regarding timeliness is applicable primarily to informal feedback. The other forms of recognition—compensation and honorifics—cannot normally be done at the moment and on the spot. However, they are important to formally “reinforce the reinforcement” and to demonstrate to the workforce that the organization backs its words with money and public recognition. Taken together, as we have said, the three means of recognition constitute a powerful package.

• Be sincere. This is an odd piece of advice; after all, a manager either means praise sincerely or he doesn’t. We can do nothing to help a manager who does not genuinely appreciate her employees’ performance. Some managers never do—they truly believe that only their efforts count—and this book is not an instruction manual in acting sincerely. Other managers, however, are sincere in their praise, yet it doesn’t come across that way to their employees. They might be so general in what they say or so tardy in when they say it that expressing appreciation seems to employees like something a manager feels he has to do rather than something he genuinely wants to do. Or, he might give mixed messages about an employee’s performance, such as, “You did well on that, but...,” or “Thank goodness you finally got that right.” Perhaps because of their own discomfort, managers might undermine the effect with “humor,” saying something like, “You’ve done such a good job, you would never know that you had an MBA,” or “He’s so loyal to the company, he hasn’t seen his family in months.” Managers can overdo it, exaggerating the achievement with meaningless flattery, such as, “The most wonderful...,” “the greatest...,” “never in the history of the company....” Although much of the advice about how to give recognition—and perhaps recognition itself—might seem trite and even corny, be assured that recognition is vitally important to employees and that employees listen carefully to every word that is said when it is given. The simpler and more direct the compliment, the better, such as, “You did a great job on... and I want you to know that. I especially liked... Thank you very much.” If the praise is exaggerated or too flowery, it won’t be believable. If it is a mixed message, the employee most remembers the negative comment or implication, even if the manager finishes on a positive note. Simply stated, people want honest and deserved acknowledgment of their contributions and, when received, it is greatly appreciated. Don’t spoil it.

• Recognition should be given for both group and individual performance. In our chapter on compensation, we suggested that, for most employees, pay for performance should be based on group accomplishments. We argued that individual reward schemes (such as piecework and merit pay) can be administrative and employee-relations nightmares that result in many employees feeling no sense of reward, and that they tend to diminish teamwork. But we must still deal with the fact that in a group some individuals contribute more than others (perhaps much more). Should—and how do—these people get recognized? In part, recognition is obtained from co-workers, especially when the pay or bonus is group based. An outstanding contributor is valued by the group under that condition because his work is financially beneficial to all (which is in contrast to the “rate buster” within individual pay systems who is ostracized because his high performance is detrimental to his co-workers).

Fully employing the three means of recognition allows both individuals and groups to receive due acknowledgment for their efforts. Although we suggest that for most workers compensation for performance be based on group performance, informal recognition by the manager will usually be given to individuals. And, as the occasion warrants, the manager will also bring the entire group together for a collective thank-you.

Honorifics, which are the formal awards, also need to be distributed to both individuals and groups. However, these should, in our view, be reserved largely for truly outstanding achievements: the organization’s “Nobel Prizes.” We suggest dispensing with the multitude of recognition awards distributed by some organizations, such as gift certificates, reserved parking spaces, dinner-for-two, and employee-of-the-month. After they are in place for a period of time, our attitude surveys never show anything better than a lukewarm response to these programs. Indeed, they generate numerous complaints, especially about who is selected for the awards and the mystery that normally surrounds the selection process. The workforce should greet programs of this type with enthusiasm—after all, they are designed to provide recognition—but they seem to have the opposite effect on most employees. Upon hearing of the complaints, management often revises the programs to distribute the awards more widely so people don’t feel excluded. As recognition for performance, most of these programs then become increasingly meaningless.

Our suggestion, then, is to have just one program (or very few) and to limit these to truly outstanding contributions. The awards should be for both individuals and groups, and the choice of awardees needs to be made by a panel that includes the employees’ peers. Including peers goes a long way toward reducing the mystery and enhances the perceived fairness of the selection process.

Advancement

We have discussed recognition and rewards within the context of the employee’s current job. However, one of the most powerful rewards for many employees is the opportunity for a promotion to a higher-level position within the organization. It is powerful because it delivers a number of rewards simultaneously: more money; more status; often, a more challenging, interesting, and influential job; and public recognition.

A major issue for employees is the degree to which their companies are committed to promoting from within. To be a bit facetious, companies can be categorized into two kinds: those that do their utmost to promote from within, and those for whom current employees are, in effect, “soiled goods.” As one manager in a client company described his organization’s philosophy when searching for a new executive,“I guess we feel that anyone who works here can’t be too smart, so we’d better get someone from the outside.” This frustration is found often in write-in comments:

Current opportunities for personal growth through promotion... are severely limited... this company brings in many people from the outside to fill critical managerial and professional positions. I don’t believe mechanisms are in place here to identify the best candidates within the company for positions when they come open.

My biggest problems with this company are recognition, growth, and promotion from within as opposed to bringing so many people into leadership roles from outside the company.

Despite messages to the contrary, I see no evidence that senior management in my business unit here are interested in promoting from within. Do they really think all the talent is on the outside? How about experience with our company and our products—doesn’t that count?

Organizations that do not adhere to a promote-from-within philosophy lose out in a number of ways:

• They send a message that they don’t have much respect for their own employees’ competence, so they lose out on the commitment and enthusiasm that respect for people generates.

• They lose out on the motivational impact of promotions and promotion prospects, which causes ambitious employees to feel stagnant and frustrated.

• They lose out on the edge that an experienced workforce—experienced in that business and industry—gives to an organization.

• They lose out on the stability of organizational goals and culture.

• They lose out on the recruitment and training costs that hiring entails.

Companies give three main reasons for not promoting from within to higher-level job openings. The most common reason is that the right persons for the positions cannot be found within the organization or significantly better persons are available on the outside. Another reason is that the organization is in such trouble—or is so stagnant—that “new blood” must be brought in. Lastly, it is argued that “high potential” people need to be hired for whom open positions—usually first-level management—provide “developmental” opportunities. These arguments make sense theoretically and are certainly valid in specific instances. If, for example, there is a need for a particular type of specialist that cannot be found within the company, that specialist will have to be hired.

However, the research that has been done supports overwhelmingly the proposition that, on the average, organizations that adhere to a promote-from-within policy perform much better than those that do not. For example, in Built to Last,5 Collins and Porras conclude from their research on higher- versus lower-performing companies that the former “... develop, promote, and carefully select managerial talent from inside the company to a greater degree than the comparison (lower-performing) companies....” In fact, the CEOs of the higher-performing companies were six times more likely to be insiders promoted from within.6

Some executives talk interminably about the flaws of the people who work for them. But when describing someone they are about to hire, that person has no imperfections; it seems that “hope springs eternal.” This is largely a pipe dream because the perfect executive does not exist, and this is discovered—sometimes with shock and dismay—after the new person is on board. The right—not the perfect—person for the job is usually under management’s noses, if only they had looked. If that person is not there, it was probably not for lack of raw material, but because that material was not developed as it would have been if an effective management succession and development program had been in place. Or, the right person was not found because qualified people left the organization, having become frustrated with the lack of opportunity for them.

It is imperative that the company first seek all possible internal candidates for an opening. To be fully effective, this policy obviously must be accompanied by programs for the identification and development of the organization’s talent.

Should companies promote only the best performers? This is an interesting and troublesome question, mostly because of the perceived danger of promoting workers to levels above their competence. The best engineer might not be the best engineering manager, or the best salesperson the best sales manager. But if the best-performing people are not promoted, wouldn’t that impair their motivation and enthusiasm? Yes, it would, and although it would be ludicrous to suggest that a promotion always go to the best performer (that employee might really be unsuited for the job), it needs to be always offered to someone from among the best-performing people. Selecting a “satisfactory” employee is a serious mistake when higher-performing employees are qualified for the job. The satisfactory employee might have all kinds of other attributes that would appear to make him more suitable for the promotion, but he has not earned the right to it. Put negatively, the high-performing employees—with the exception of the clearly unqualified—have earned the right to fail, and it is most unlikely that a reasonable candidate would not be found among those employees.

The Other Side of the Equation: Dealing with Unsatisfactory Performance

From time to time in this book, we have referred to employees whose performance is clearly and continually unsatisfactory. Most of these people should not remain in the organization, at least not in their current jobs. Such employees constitute a small percentage of any workforce (rarely more than 5 percent), but they consume an inordinate amount of management’s time.

Employees who are clearly and continually unsatisfactory come in three general varieties:

• Those who, with competent guidance, clear goals, and considerable encouragement can improve to a satisfactory level in their current positions.

• Those who are in the wrong job and will not improve until they are correctly placed.

• Those who do poorly no matter how much guidance they receive or in what job they are placed.

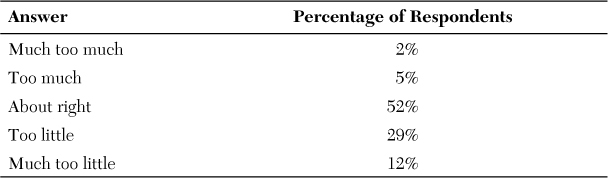

Not dealing with poor performers has morale consequences for their co-workers. In fact, among the largest and most consistently negative employee survey findings are those about the organization’s approach to poor performance. When asked, “How do you feel about the extent to which (the organization) faces up to poor performance?” the percentages obtained, on the average, are revealing (see Table 10-1).

It is not that 41 percent of employees (29 percent plus 12 percent) are seen as poor performers. The poor performers are typically a small percentage of any employee population, usually just one or two people in an individual department. However, they aggravate many employees. What is especially discouraging is management’s perceived unwillingness to confront this problem and do something about it. The problem is clear to everyone, and there is usually no disagreement among the workers as to who the culprit is. In focus groups, they almost always point to the same person—sometimes literally!

In a focus group we conducted in a government agency, the group consisted of all ten employees in a particular section. A major complaint expressed by many of the participants was that one employee in the section “loafed all day.” The discussion about this employee went on and on even though that person must have been present because everyone in the section was there. The discussion finally shifted to another topic, and a worker who had been quiet up until then began to participate. The rest of the group in seeming unison nodded at the moderator; they had subtly let him know who the loafer was.

The consensus among co-workers is not just about the culprit, but about the reason for the poor performance and the solution. Employees are insightful when it comes to diagnosing the problems their co-workers are having, such as a lack of training or a mismatch between employee and job. (“He’s just not a salesman.”) About others, they say simply that, “Nothing can be done about him.” They want help given to those they feel can be helped and, understandably, have mixed feelings about what to do with employees they consider incorrigible. Employees typically do not want their colleagues fired, but they become reconciled to it and supportive if they believe that management has done whatever is reasonable to help the employee improve and has otherwise treated him fairly.

Whatever the reason for poor performance, it is critical that it be dealt with quickly, squarely, and fairly. The first step is to provide guidance in a way that conforms to our previous suggestions, including the opportunity for the employee to express what he believes the problem to be and what the solution might be. Improvement goals should be set and follow-up done to assess whether satisfactory performance—or at least sufficient progress—has been achieved. If not, and enough time has elapsed, the manager (in consultation with his management and usually with Human Resources) needs to decide whether the appropriate solution is to transfer the employee to another job in the organization or to fire him. Transfers should not be sought for two kinds of employees: those unlikely to have the ability for any job in the organization (why continue the torture?), and those who have the ability but whose personality (overly rebellious, overly passive, totally disorganized, just plain lazy, and so on) would make them a poor risk as an employee anywhere.

We won’t review the legal and administrative requirements that govern the firing of employees, such as providing sufficient notice to them of impending action and having adequate documentation. Suffice it to say that those requirements need to be followed, and not just to avoid lawsuits and penalties. Although it is time-consuming and costly to abide by the rules, they are there to provide necessary protection to employees against arbitrary actions by management, and abiding by them reinforces confidence throughout the workforce in management’s fairness.

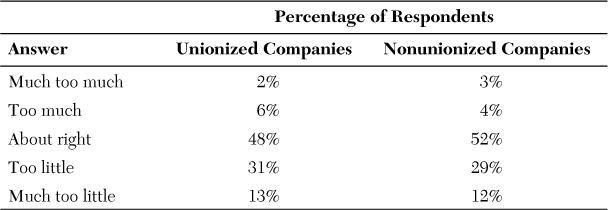

Management frequently blames unions or civil-service regulations or Human Resources departments for the delays in dealing with poor performers. To the extent we have been able to study this, our data do not bear this out. The problem of management’s unwillingness to face up to poor performers appears unrelated to those variables. For example, our data show little difference between the way workers in unionized and nonunionized companies respond to the question about the company facing up to poor performers (see Table 10-2). The problem, therefore, appears to lie largely in management, not in the constraints that unions impose.

Table 10-2 Response to the Question “To What Extent Does Your Company Face Up to Poor Performers?” by Union and Nonunion Workers

Feedback Sets Priorities

An extremely important function of feedback, both cognitive and affective, is to convey messages to the workforce as to what the organization’s priorities are. Employees quickly learn that what companies say in their formal pronouncements—such as in their vision and values statements—is less important than what they hear from their managers day-to-day at work and how their financial and other rewards are determined. If, for example, a company preaches customer service, but employees in a customer call center hear from their managers only when the quantity of the calls they process is insufficient, they learn that it is quantity—not quality—that really counts. If the company talks about ethics but winks at employees cutting corners as long as the numbers come out “right” (in fact, may reward them for those numbers), the message about ethics to employees is clear: don’t take them too seriously. If the company talks about “excellence in everything we do” and does nothing about poor performance, “excellence” becomes a high-sounding word with little relevance for how the organization actually runs.

An explicit vision and values statement is beneficial only if the company takes it seriously, which means bringing the messages conveyed by performance feedback and recognition into line with that statement. That is the reason why, in Chapter 7, “Organization Purpose and Principles,” we emphasized the importance of implementation. It is only through the implementation of overarching goals and values that employees learn what the organization really cares about. Having serious gaps between words and deeds is worse than having no words at all because the gaps breed employee cynicism about management’s competence or motives.