1. Introduction: Setting the Stage

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Set the stage for the discussions in this book

• Discuss the concept of costs versus expenses

• Explain the concepts of OPEX and CAPEX

• Examine various compensation and benefit elements

• Discuss in detail the concept of base salary

• Discuss the treatment of compensation and benefit elements within current accounting systems and structures

• Discuss the current accounting for human resource cost outlays

• Explain the current payroll accounting process for hourly and salaried employees

This introductory chapter examines how finance and accounting principles apply to compensation and benefit program design. The discussion analyzes the current connections and proposes various connection enhancements. In this chapter, you also learn the terms commonly used with regard to compensation and benefits. The chapter also proposes modifications to the accounting process to accommodate a revised classification of compensation and benefit cost outlays and transactions. Thus, the chapter lays the foundation for the finance and accounting analysis of compensation and benefit transactions.

The words cost and expense are often used interchangeably. Are human resource (HR) outlays costs or expenses? What is the difference? Where in the accounting structure and system can one find HR expenditures? Are the current classifications within the accounting framework appropriate? What changes can one anticipate in the current expense/cost classification resulting from the changes in how work is currently done and how it will be done in the future? These and other questions need to be answered before discussing the various specific techniques and analytical mechanisms within the finance and accounting structure that affects HR management (and specifically compensation and benefits).

In this chapter, after answering some critical questions posed here, the basic flow of compensation and benefits outlays,1 as defined by HR departments, is traced through the accounting framework and structure.

The Cost Versus Expense Conundrum

The words cost and expense are used interchangeably in accounting. But a cost incurred can be an asset or expense depending on the timing of accounting transactions and the concept of periodicity.

Especially in transactions like the acquisition of a physical asset, the cost classification can become an important decision. When a physical asset is acquired, many costs might be involved (for example, purchase price, freight costs, and installation costs). So, the accountant has to decide which cost to include as an asset and which costs to expense immediately. Those costs that are expensed immediately can be called revenue expenditures. And costs that are not expensed immediately but are included in asset accounts are referred to as capital expenditures. Some firms call these expenses operating expenses (OPEX) and capital expenses (CAPEX). You’ll read more about these classifications later in this chapter.

An expense is, in actuality, a cost used up while producing the sales revenue for the business. In other words, expenses are those monetary outlays that flow through to the income statement. In contrast, costs that have not been used up remain a cost and are reported on the balance sheet as an asset. Expenses are those costs that are necessary to make sales within a specific period. A company can incur a cost and spend cash to pay rent in advance for a six-month period, for example. On the day this transaction is made, however, a debit entry is made to an asset account called Prepaid Rent. Only after a month is over and the premises have been occupied for that month does an expense transaction occur, and for that month only; five months of the cost incurred for prepaying the rent stays on the balance sheet as an asset.

Let’s take another example. Suppose a restaurant is gearing up for a Christmas banquet for a big corporate event. The owners go out and buy nonperishable restaurant supplies such as napkins and so forth. The cost of this cash purchase is $5000. Now let’s suppose they use up 30% of these supplies for this big corporate banquet. In this case, $1500 is classified as an expense for that period (the month and year when financial statements are prepared) and the remaining $3500 will still be a cost but will be reported on the balance sheet as Restaurant Supplies (an asset). In this case, this cost—an outlay of cash—is both an asset and an expense.

Now, suppose that a business buys a piece of land to build a factory. The cost of that land never becomes an expense. That cost continues to be classified as an asset (because land is never depreciated).

If a hospital buys an MRI machine, any cash or credit purchase is first carried as an asset on the balance sheet. Then, after that, a periodic depreciation expense is recognized in the income statement. So, here again, the entire cost of that MRI machine is not an expense at the time of purchase. Instead, the expense is spread over the useful life of the MRI machine. As a matter of fact, the historical cost of acquiring the MRI machine is always shown on the balance sheet. Depreciation taken each period is recorded as a period expense and also recorded as a contra-asset in an account called accumulated depreciation.

Now consider manufacturing businesses: Cost outlays within a given period for direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead directly used in making products that were sold within that specific time period are considered expenses for that period and are termed cost of goods sold. Cost of goods sold flows into the income statement and is matched with revenue earned during that period. But direct materials, manufacturing overhead (which includes indirect labor), and direct labor remaining in finished goods or in work in process are considered assets. Therefore, here again, not all costs are expenses. Some are assets (balance sheet), others are expenses (income statement). So, in current accounting practice, some employee monetary outlays are assets, some are expenses.

Furthermore, other transactions in a manufacturing company are considered selling, general, and administrative expenses for a specific period. Compensation outlays for the truck driver who delivers materials to the factory are considered expenses for a period. In contrast, electricity used in the factory might be either an asset or an expense depending on whether manufacturing overhead, including factory electricity, is assigned to products as cost of goods or as work in process inventory or finished goods inventory. But all electricity used in the administrative offices is considered an expense for a particular period.

Adding to the confusion, let’s consider monetary outlays for research scientists. Suppose that a firm buys a laboratory machine for a research lab. The cost of this machine might be $20,000, with an additional $5,000 expense for installing the machine. As of the date the firm acquires this machine, the accounting system increases an asset account by debiting that account with the total purchase cost of the machine plus all costs necessary to make the machine ready to use. And then the accountant periodically records a debit entry to a depreciation expense account spread over the useful life of the machine, using an acceptable depreciation schedule. This expense is then reported in the income statement, matching it against the current period revenue.

If the same firm were to hire a research scientist during the same period, however, the costs that the firm incurred to hire that scientist—recruitment advertising, search fees (which can be quite large), interviewing costs, and other hiring costs—will all be currently expensed and reported in the income statement. This can lead to a distortion in income measurement because the research scientist’s service will extend over more than one year. But currently, the accounting rules require that all the HR cost outlays be expensed during the current period.

Compensation-related outlays for these scientists are all considered expenses for the current period. In accounting systems, though, the cost outlays for physical products (the machines the scientists use) are considered assets and are expensed only over a period of time (their useful life).

The issue of reporting intangibles also needs to be discussed in connection with the recording of HR outlays. Under current accounting standards, intellectual property that an employee brings and utilizes within the employment setting is not considered a recognizable asset. The current accounting system records as assets only certain other intangibles such as copyrights, patents, and trademarks. The irony is that the intangibles are the outputs of the employees with specifically valuable intellectual property.

In many cases, a big difference can exist in book value versus market value of the assets. For example, in a recent year Google had stockholder equity of $22.7 billion, whereas its market value during the same period as determined by multiplying Google’s market price of its shares by the number of outstanding shares was about $179 billion. Such a wide difference undermines financial reporting. It can be assumed that most of this big difference results from nonrecognized intangibles. And one of the biggest intangibles is the value of Google’s human assets. Part II of this book discusses this concept in greater detail.

So, one can safely say that confusion abounds within current accounting standards frameworks as to how and where HR monetary outlays are classified in accounting systems.

CAPEX Versus OPEX

The expressions capital expenses and operating expenses are often used in accounting and finance. Cost or expenditure outlays can either be capitalized (spread out over a period of time) or taken into a specific time period’s profit/loss—in other words, in the time period they were incurred (revenue and expense recognition). This is the difference between capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operating expenditures (OPEX).

With reference to these classifications, employee-related expenditures are classified differently by different groups. The HR-related cost or expenditures can be classified either as CAPEX or OPEX. CAPEX remain capitalized (a balance sheet classification) until these transactions become expenses for a specific time period. HR accounting proponents suggest that for effective management reporting it might be better to aggregate these accounting entries into one account. If done, it gives business decision makers a more complete picture when making strategic and operational decisions affecting employees.

The Current HR Cost-Classification Structure

Let’s now examine the fundamental elements covered in this book. First, it is important that you understand the terminology commonly used in compensation and benefit analysis. After reviewing this terminology, the discussion turns to these terms within the context of the current accounting framework.2

Compensation and Benefit Elements

The most commonly used terminology related to compensation and benefits within the organizations are as follows:

• Base salary: Base or basic or fixed pay describes the “fixed” part of pay. This pay element is mainly paid to employees to come to work (to attract employees). It is also paid to employees to do the assigned work by applying the required skills, knowledge, and abilities using normal effort and demonstrating necessary work behaviors. Basic pay is usually the largest component of the total pay package. In other words, basic pay is the amount of nonincentive wages or salaries paid over a period of time for work performed. It may include additional payments that are not directly related to the work effort.

Compensation professionals use the following methods to determine base pay levels:

• Skill- or competency-based pay

• Market-based pay

• A combination of these three

Compensation books adequately explain these methodologies.3 The professional organization WorldatWork4 conducts seminars and develops various publications explaining these methodologies. Some compensation specialists have tried to define precisely the distinctions between the terms base pay and basic pay.

Chuck Czismar, in a blog post5 from January 6, 2010, attempts to create a distinction between the terms base pay and basic pay. He says that base pay refers only to “non-incentive wages and salary paid out over a twelve month period for work performed.” He goes on to define basic pay as “the amount of non-incentive wages or salary paid out over a twelve month period for work performed, but including additional payments not directly related to work effort.” He seems to be referring to additional variable pay allowances and to 13th and 14th month payments, prevalent in various countries.

The term fixed is used to distinguish this pay component from others that are of a variable nature, such as bonuses, incentives, and various contingent payments.

Base compensation has other flows (or changes), as well. Here is a list of the cost flows (changes) that affect the base pay in total:

• Part-time status to full-time status

• Full- time status to part-time status

• Change of status to nonpaid leave

• A temporary allowance (on and off)

• A temporary adder (on and off)

• Exempt employee to nonexempt and vice versa in the United States

• Promotion increase

• Annual performance increment or merit increase

• Salary reductions

• Overtime payments

• Workers’ compensation (on and off)

• Salary differentials (on and off)

• General increases

• Step increases

• Cost-of-living adjustments

All these variables affect the total base pay expenses and therefore the total costs for employees in an organization. To understand the real impact of employee-related expenditures, there is a need to record and analyze all these expense triggers. Also to forecast or budget these expenditures, all these inflows and outflows need to be documented, tracked, and analyzed. But the current accounting systems do not identify these flows separately in any detail. The payroll systems aggregate these pay transactions into a composite gross rate. To the accounting structure, it is not important to keep track of the various employee flows (although some of these flows could be tracked separately by payroll systems but not by accounting systems).6 If the salary is stated in monthly terms, these individual expense transactions are tracked in the aggregate monthly stated salary.

• Incentive compensation: Incentives or bonuses payments are paid to an employee for achieving time-bound goals and objectives. Terms such as incentive targets, objectives (bonus objectives), measurements, and ratings are all contextual terms used in most organizations. Incentive compensation refers to contingent payments paid to employees only when certain predetermined financial or individual objectives are met.

• Allowances: Allowances are usually temporary adders to the basic pay. Housing allowance, transportation allowance, and education allowance are common. Allowances are widely used in various countries. Allowances are paid for special situations or conditions.

• Pay adders: Adders to base pay are common in the United States. Overtime pay, callback pay, on-call pay are examples of pay elements and are provided for work that is done beyond normal working hours. These adders are governed by wage and hour laws in most countries.

• Risk benefits: Risk benefits are payments made for medical, disability, and life (actually death) situations. The benefits in this category are provided to employees in lieu of direct cash payments to mitigate the various life risks for employees and their families.

• Retirement benefits: Retirement benefits are common compensation elements that organizations provide to assist employees with their post-employment lives. Retirement benefits can take the form of defined benefit or defined contribution plans.

• Equity compensation: Employee equity programs in the past had been mostly provided to senior executives to motivate them to increase shareholder value. This component of pay has seen sweeping accounting changes over the past ten years or so. There has been a growth of many different structures for these plans; nonqualified stock options, incentive stock options, restricted stock options, stock appreciation rights are a few. Accounting, tax, and legal implications are integral to the design, development, and administration of these programs. More recently, issues surrounding executive compensation excesses, earnings management, insider trading, ownership culture, stock option pricing and expensing, dilution effects, and overhang have all clouded this pay element with a lot of debate and discussion.

• Perquisites: Perquisites are elements of compensation that are normally paid to senior executives. The practice is widespread around the world. Most common are first-class travel, executive jets, country club memberships, executive physicals, and financial planning. Perquisites can be direct cash payments or are compensation payments in the form of expense reimbursements for approved executive benefits.

• Expatriate compensation: Expatriate compensation is made to employees who are sent by companies to live and work abroad. Within this overall category, there can be many subcategories of payments. Among them are cost-differential payments, housing differential payments, education allowance, tax protection or tax equalization payments, moving expense allowances and foreign-service premiums, and hardship and special area allowances. An expatriate assignment occurs when an employee is transferred to a foreign jurisdiction (different from the headquarters country or the employee’s country of permanent domicile).

The appendix at the end of this chapter describes all the terms and words used in the field of total compensation. This will set the stage for a comprehensive analysis of the finance and accounting implications involved in compensation and benefit plan design.

The Current Accounting for Compensation and Benefit Cost Elements

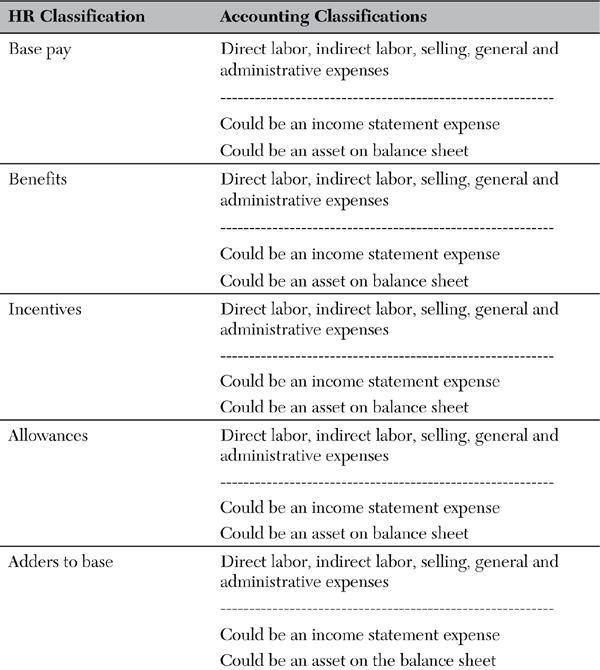

Now that you know the commonly used terms in compensation and benefits, let’s explore how these compensation and benefits cost elements are reflected in accounting systems.

If an employee’s job entails directly producing a product (as part of a manufacturing operation), accounting systems classify that employee as direct labor. Another common identifier for this grouping is touch labor. Touch labor refers to those people required to touch the product during the manufacturing process. Those employees who are involved in the manufacturing process but are involved in a supporting activity (such as the manufacturing manager or the janitor who cleans the factory floor) are included in manufacturing overhead. A commonly used term for this category is indirect labor. In cost accounting, manufacturing overhead is absorbed into unit product costs through various mechanisms, such as job order costing and process costing. All the specific compensation elements are lumped together by the accounting process into two accounts, normally called direct labor or indirect labor. Both of these account categories become a part of the cost of goods sold cost.

For manufacturing companies, the gross profit is calculated by subtracting cost of goods sold from the revenue. In accounting, therefore, the employees directly involved in making a product contribute toward the achievement of the gross profit of an organization. And in manufacturing, companies’ monetary outlays for those employees not involved in making the product are considered period expenses. Normally these expenses are part of the selling, general, and administrative expense account. The selling, general, and administrative expense and other indirect expenses are deducted from gross profit to derive the net income or loss.

Cost of goods sold in the service industry refers to the cost of the employees or machines directly involved in providing the service. Other items like electricity to run the machines and those employees who are not directly connected to providing the service are usually included as part of selling, general, and administrative expenses. This is an overhead or indirect expense. And as stated before, these expenses are deducted after the gross profit is calculated, to arrive at the net profit or income.

Let’s look at an example for a construction company. In a construction company, the compensation paid to workers directly involved in construction activities is a part of cost of goods sold, whereas employees who support them (estimators, clerks, material handlers) are included in the selling, general, and administrative expenses.

Note that the actual practice of classifying employee expenses either in cost of goods sold or in overhead expenses can vary from company to company.

In a merchandising business, there are no raw materials, work in process, or finished goods accounts. There is only a merchandise inventory account. All purchases of goods bought for resale become a part of the merchandise inventory account. Only when a specific item sells is the acquisition cost of that item then transferred from the merchandise inventory account to the cost of goods sold account. It is then subtracted from sales revenue to derive gross income or profit. In merchandising businesses, all employee expenses are classified into general expenses, which appear on the income statement after the calculation of gross profit or income.

In financial reporting, some employee costs are included in the asset section of the balance sheet. In addition, employee-related monetary transactions are often included in the balance sheet in a liability account called salary or wages payable. This suggests that some earned wages have not been paid to employees.

A case can be made that most HR cost outlays can be classified as assets. This argument might have some merit if you consider that the compensation paid to software engineers, scientists, electronic engineers, and development engineers is a CAPEX. A case can be made that these types of employees are indeed the true assets of a company, especially in high-technology and biotechnology firms. They have rare skills, and losing one of these critical skills might result in a decrease in the value of a business. But current accounting thinking does not concur with this line of thought. Current accounting standards state that expenditures should be included in financial statements only if they are clearly measurable in monetary terms and there is reliability and relevance. The accounting profession asserts that there are problems in determining relevant and reliable values for human assets. Accountants believe that human capital measurements are not up to par on reliability and accuracy. If accurate measurements are found, perhaps human capital values can be included in financial statements. But most likely, they would appear as footnote disclosures.

The point to note here is that the HR and payroll systems are identifying employee expense outlays differently from accounting systems. Accounting systems do not capture the true cost flows for the HR financial outlays.

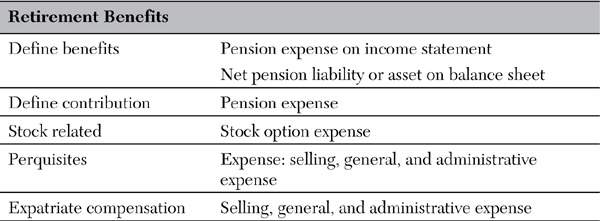

Exhibit 1-1 summarizes all the compensation and benefit cost flows. In one place, it shows the accounting flows of all total compensation elements and also indicates the accounting classification most likely used to record these transactions.

Exhibit 1-1. A Summary of the Flows

The Accounting of HR Cost Outlays – How Payroll Systems Work

Now that you understand cost and expense classifications in general and the HR designations of employee cost outlays, this section covers how accounting systems currently report employee cost transactions in the accounting cycle.7

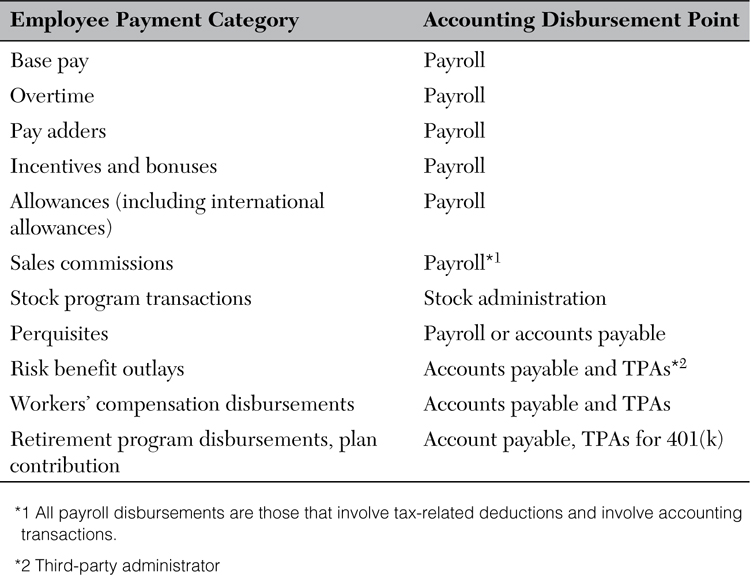

Payroll departments are responsible for making payments to employees. But not all employee payments are transmitted from the payroll department. Some payments are made as expense reimbursements.

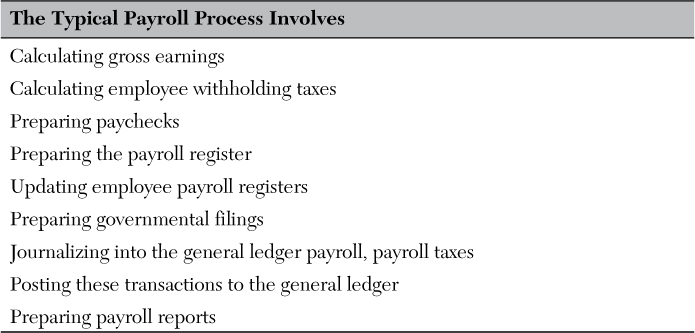

Exhibit 1-2 shows the payment transactions normally disbursed from payroll departments.

Exhibit 1-2. Payment Transactions Made from Payroll Departments

Exhibit 1-3 indicates in summary form how a typical payroll process works, which we explain in more detail.

Exhibit 1-3. Payment Transactions Made from Payroll Departments

In addition, payroll systems track payment transactions differently depending on how pay is recorded in HR processes and systems. Employee designations commonly use designations such as salaried, monthly, weekly, or hourly. It should be noted that these are payroll-related computational designations rather than what is conventionally thought–an employee ranking or status designation. If an employee is designated as an hourly employee, the computations in the payroll system might be as in the following example.

Suppose that John Peters is one of six hourly (non-exempt) employees who work for Bagan, Inc. Bagan has a biweekly payroll process. Let’s also say that the biweekly period starts on March 16 and ends on March 30. The first week of this period started on March 16 and ended March 23. And during this period, John worked for 46 hours. Federal law in the United States stipulates that any nonexempt employee who works for more than 40 hours a week needs to be compensated at a time-and-a-half rate for those extra hours.8 In this case, 6 hours are over the 40-hour limit. Suppose John’s hourly rate is $25.20. In that case, his weekly gross pay is calculated in this manner:

40 hours @ $25.20 = $1,008.00

6 hours @ $25.20 × 1.5 or $37.80 = $226.80

Total gross earnings for the week = $1,234.80

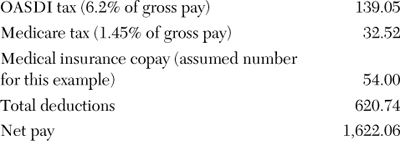

In the United States, tax is withheld from the gross wage income (which for John Smith is calculated based on his documented deductions on his W-4 form and withholding tax publication–Circular E, provided by the Internal Revenue Service). After that, state income tax withholding is also deducted from gross pay. In addition, the payroll department must withhold Social Security taxes or FICA (Federal Insurance Contribution Act). This tax is actually two taxes. One tax is called the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI), and the other is known as Medicare (hospital insurance). The rates for OASDI and Medicare are, respectively, for 2012, 6.2%9 and 1.45% of gross wages. In addition to these deductions, other deductions will be needed, such as the employee portion of an employee health insurance program (if there are any for the organization).

To further illustrate the gross earnings to net earnings calculation, now let’s assume that for the second week, the March 26 to March 30 pay period, John worked 40 hours.

The federal withholding tax is derived after the employee completes and submits Form W-4, Employee’s Withholding Allowance Certificate. This amount is based on marital status and the total number of dependant allowances claimed on the certificate. The amount of tax withheld is provided in the wage bracket table, published by the IRS in Circular E.

Note

The state income tax withholding is calculated in a similar manner using allowances provided on the W-4 form and by using state publications published for the purpose of calculating withholding taxes.

Other possible payroll deductions and adjustments include the following:

• City and county taxes, if any

• Before-tax employee contributions

• 401(k) employee contributions (disbursed to TPAs*)

• Health savings account (disbursed to TPAs*)

• Flexible spending accounts (disbursed to TPAs*)

• Federal Unemployment Tax (FUTA)

• Statement Unemployment Tax (SUTA)

• Employer-matching contributions for 401(k) plans

• Workers’ compensation premiums

• Employer portion of Social Security taxes paid on behalf of an employee

Accounting Record Keeping

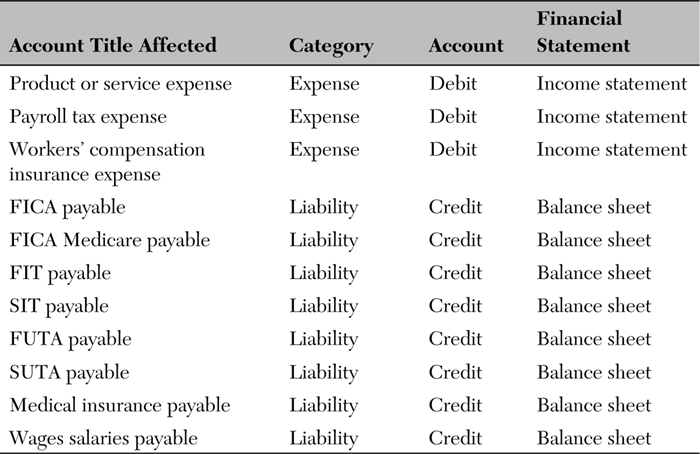

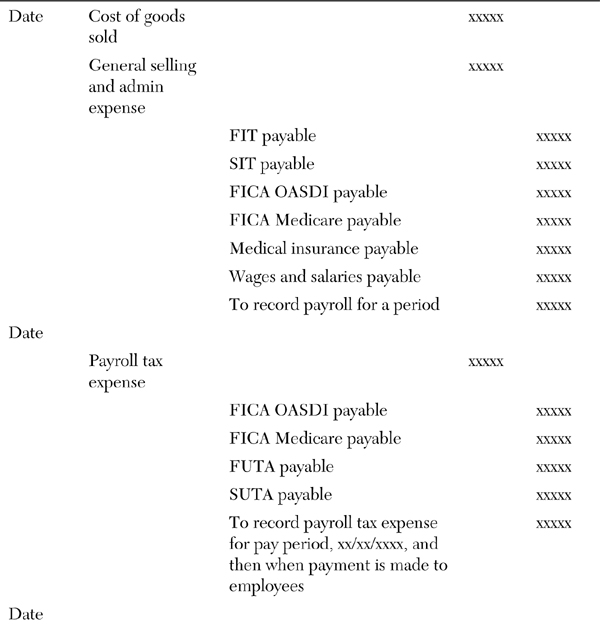

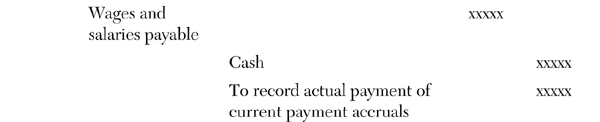

In the accounting process, employee payment transactions are journalized, posted to the ledger, and recorded in the financial statements in the manner shown in Exhibit 1-4.

Exhibit 1-4. Employee Payment Transactions

This is not necessarily the case in manufacturing companies, where employee payments can be a part of work in process, finished goods, or cost of goods sold. Exhibit 1-5 gives a description of the accounting entries recorded for payroll transactions.

Exhibit 1-5. Accounting Entries for Payroll Transactions

Note here that after these transactions are incurred they become payables and remain on the balance sheet until those outlays are paid out from cash. At that point, those transactions become income statement accounts.

Accounting for Payments Made to Salaried Employees

For employees who are classified as salaried, the payroll status is normally stated as a monthly wage. This is not a job-level designation. It indicates that in the payroll system these employees’ compensation payments are recorded on a monthly basis. In the United States, salaried employees are usually exempt from the provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act. In other words, they do not have to be paid overtime for any hours they work over 40 hours in a week.

Federal law in the United States that governs overtime earnings is called the Fair Labor Standards Act, which is part of the federal wage and hour legislation. All employers engaged in interstate commerce have to adhere to the Fair Labor Standards Act. There are also state wage and hours legislation with which employers must comply.10

The payroll system pays these employees their fixed monthly salary on each pay date. If the pay period is biweekly, these salaried employees are paid their monthly rate divided by two. The stated salary rate will be gross pay from which the employee’s specific payroll deductions are subtracted. These deductions are similar to those used for hourly employees (as described earlier in this chapter).

Other Technical Payroll Accounting and HR Issues

First, there is the issue of thirteenth- and fourteenth-month payments made in many countries outside of the United States. Normally, in the United States, the workday is 8 hours in duration. In a 52-week year, that makes 2,080 work hours in a year:

8 hours a day × 5 days a week × 52 weeks in a year = 2,080 hours

In the United States, the number of hours employees can work is 2,080. But we know that most employees take at least two weeks of vacation during the year. Those two weeks are paid vacation days. Therefore, in the 52-week year, the employee does not necessarily work the entire 2,080 hours. If the employee takes a two-week vacation, he or she actually works 2,000 hours. But, employees are paid their annual stated salary. This is because a salaried employee’s stated salary is an annual amount. It could also be stated on a monthly basis. In the latter case, you just have to multiply the monthly salary by 12 to get the annual stated salary. Therefore, in the United States, paid vacation is built in to the annual or monthly stated salary. Holiday pay is treated in the same manner.

In some countries, the monthly or annual salary covers only hours actually worked. The vacation is paid as an extra month: the 13th month. The 13th-month payment is identified differently in different countries. In some countries, it is a bonus granted to all employees. In other countries the Christmas bonus is a legal requirement. The additional-month payment adds to wage costs. In Greece, which is in economic chaos, the payment of the 13th month has become a political issue.

The main purpose of this chapter was to explain how the accounting process and the HR process classify compensation and benefit elements. As you learned, to accurately understand and record HR financial transactions, processes have to be developed to record these expenditures to better understand their impact on operational and strategic business decisions. For example, the critical strategic and operational decision about workforce reductions is often made based on accounting data, which is much narrower in scope than HR inflows and outflows classifications. If a more broadly scoped HR accounting data-gathering process were adopted, business decision makers might not be as willing to terminate the services of thousands of people so readily. As you know, workforce reduction results in devastating consequences for those employees who lose their jobs and for society as a whole.

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Flow of compensation and benefits cost outlays

• Costs versus expenses

• CAPEX

• OPEX

• Compensation and benefits cost elements

• Understanding base pay

• Base pay outflows

• Current accounting for compensation and benefit cost elements

• Payroll accounting

• Record keeping of HR cost elements within the accounting cycle

• Technical issues with respect to compensation and benefit cost elements

• The definition of all compensation and benefit terms

Appendix: The Terms

This appendix describes compensation and benefit terms in more detail than described in the main body of this chapter:

• Base, basic, fixed, “come to work” pay: The “fixed” part of pay. This element is provided to employees to come to work and do the job by using the required skills, knowledge, abilities, and appropriate work behaviors. Usually, this component is based on market rates combined with some measure of the internal ranking for the job or position, normally through a job-evaluation system.

Base pay can also be identified in many other ways:

• Wage: A fixed regular payment typically paid on a daily or weekly basis by an employer to an employee classified as a manual or unskilled worker. In economics, wage is the part of total production that is the return to labor as earned income as compared to dividends received by owners. Some contend that wages are paid to daily workers who are not necessarily employees. The implication is that the word wage is used to define the money a worker receives in exchange for labor (that is, physical labor). There seems to be a connotation that wages are given in exchange for physical labor and not brain power (physical strength in contrast to intelligence).

• Salary: A fixed regular payment typically paid on a monthly or biweekly basis but often stated as an annual sum. This is payment made by an employer to an employee as opposed to a worker. In other words, it is a payment made to a professional or a white-collar worker. A salary is a form of periodic payment from an employer to an employee, as stated in a recruitment contract. The payment differs from wages. In wage payments, each job or hour is paid separately. The distinction between salary and wages flows from the fact that for salaried employment the effort and output of “office work” is hard to measure in hourly terms.

• Compensation: The money received by an employee from an employer as a salary or wage. Therefore, the word compensation is used as an encompassing word covering both wages and salaries. But the pure definition of this word is money awarded to a person to compensate that person for his or her time, effort, abilities, knowledge, experience, and skills provided to an employer. This is the basis for an exchange; employer pays compensation, the employee provides the employer various personal attributes. When the exchange is not fair from the point of view of either party, there is dissatisfaction. Effective compensation is based on various motivational theories. A discussion about the theories is beyond the scope of this book.

• Pay: Pay means the giving of money to someone that is due to him or her for work done. In other words, it explains the giving of a sum of money in exchange for work done. It also alludes to giving what is due or deserved. The notion of payment arose from the sense of pacifying a creditor. I want to pay him for his work (reward him, reimburse her, compensate him, give payment to him or her, or remunerate him or her).

In the current context, this concept needs some thought. It is not just wages or salaries that are being provided. Organizations are paying their human resources; they are rewarding, they are remunerating. The concept here is that the word pay should include both the perspectives of the giver and receiver of pay. This is a psychological transaction as much as it is an economic transaction. Both the supply (what the organization wants to provide) and the demand side (what the employee, who is the creditor being pacified) of the equation need to be considered to make the transaction fair to both parties.

All too often, organizations (both private and public) look at only the supply side and ignore the demand side (what the employee wants), and therefore pay remains one of the most emotionally disturbing work conditions.

• Remuneration: One will receive adequate remuneration for the work one has done (that is, a payment, pay, salary, wages; earnings, fees, reward, compensation, reimbursement; formal emoluments). So, this word is also an all-encompassing word.

• Rewards: A payment given in recognition of service, effort, or accomplishment. Today, the concepts behind the terminology listed here continue to evolve as part of a system of reward that employers offer to employees. Salary (also now known as fixed pay) is coming to be seen as part of a total rewards system, which includes variable pay (such as bonuses, incentive pay, and commissions), benefits and perquisites (or perks), and other schemes employers use to link reward to an employee’s individual performance. Tying it into performance in a clear, understandable, and acceptable way remains a continuing challenge. Good in theory, but fraught with real-life issues.

• Incentives or bonuses: These payments are provided to employees for achieving time-bound goals and objectives. Words such as incentive targets, objectives (bonus objectives), measurements, and ratings are all contextual terms used in most organizations. In economics and sociology, an incentive is any factor (financial or nonfinancial) that enables or motivates a particular course of action. These payments or gifts are added to what is usual or expected. Incentives are often amounts of money added to wages on a seasonal basis, especially as a reward for good performance (for example, a Christmas bonus).

• Allowances: These items are not benefits but are additional cash payments for special circumstances. These types of allowances are widely used in various countries. They are sums of money paid regularly to a person, specifically to meet specified life needs or expenses. It is an amount of money that can be earned or received free of tax or tax neutralized; examples are housing, education, hardship, transportation, special area allowances, foreign service premiums, and tax protection or equalization payments.

• Adders to base: These payments are common in the United States. Overtime pay, callback pay, and on-call pay (also called beeper pay) are common elements provided for work that is done beyond normal work hours or under special circumstances. Overtime is provided for work done over standard legal working hours. Callback pay is special pay provided to technical workers who are called back to work after normal hours because they are needed to address a specific or an urgent situation. On-call pay is similarly an additional amount paid to employees who are required to be on-call by their employers to come into work when asked to do so. Beeper pay is provided to employees who have to keep electronic beepers on all the time so employers can access the workers on short notice.

• Risk benefits: Medical, disability, and life insurance. These benefits are provided to employees in lieu of cash to mitigate the various life risks faced by employees and their families. Employee benefits are regarded as nonwage compensation provided to employees in addition to their normal wages. Benefits can be regarded as transactions where the employee exchanges (cash) wages for some other form of economic benefit. This is generally referred to as a salary-sacrifice arrangement. In most countries, employee benefits are taxable at least to some degree. Some of these benefits are group insurance (health, dental, life, and so on), medical payment plans, disability income protection, daycare, tuition reimbursement, sick leave, vacation (paid and nonpaid), and Social Security. The purpose of the benefits is to increase the economic security of employees and protect them from unfavorable life situations.

• Retirement plans: Employers provide these benefits to assist employees with their post-employment lives. Usually there are two categories of retirement plans: the defined benefit plans and the defined contribution plans. Defined benefits plans are formula based, and defined contribution plans are contribution based. The contributions are made by participating employees. The fundamental objective of these plans is to provide an income-replacement payment. With this payment, participating employees should be able to replace a certain portion of their preretirement income during their retirement years.

• Equity compensation: This element in the past was mostly provided to senior executives to motivate them to increase shareholder value. But the equity compensation component of pay has seen many changes over the past ten years or so. There are many versions of these plans: nonqualified stock options, incentive stock options, restricted stock options, stock appreciation rights, among others. There are many accounting, tax, and legal implications to these plans. Some of the issues being discussed within this context are ownership culture, stock option pricing, dilution, and overhang. The equity compensation element has spawned specialists, legal experts, associations, and interest groups (each with their unique opinions and viewpoints). The important issues in equity compensation are (1) whether these programs have any value if distributed all across the whole employee population, even to the lowest employee levels, and (2) whether the organizations that distribute stock options widely to all levels of employees achieve an “ownership culture.”

• Perquisites: Many companies provide executives a wide variety of perks. This practice is widespread around the world. The term perks is often used colloquially to refer to payments because of their discretionary nature. Often, perks are given to employees who are outstanding performers and those who have seniority. Common perks include company cars, hotel stays, free refreshments, leisure activities during work time (golf and so on), stationery, and lunch allowances.