6. International and Expatriate Compensation

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Explain theoretical and structural concepts in international and expatriate compensation systems

• Explain the balance sheet system for expatriate compensation.

• Discuss the allowance structure within the balance sheet system

• Review the concepts underlying the expatriate income tax system

• Explain the methodologies used to calculate the cost-differential allowance

• Examine the issues surrounding the global payroll system

• Discuss the main challenges in establishing international employee pension plans

• Set overall framework for the design of global stock option plans

International and expatriate compensation is one of the most technically involved aspects of human resource (HR) management. The technical issues involved with design, development, implementation, and administration of such systems require expertise of accounting, finance, statistics, law, and taxes. These technical issues are interwoven into the various facts of international and expatriate compensation programs.

This chapter discusses international and expatriate compensation, with the technical issues as the focus. But, first we review the theoretical and structural basis for the programs. Our discussions, true to the purpose of this book, will stay focused on the technical accounting, finance, and statistical issues.

The topics in international and expatriate compensation that have a significant finance, accounting, and statistical content are as follows:

• Expatriate taxes

• Cost-differential allowance calculations (has more of a statistical focus)

• Costing expatriate assignments

• International and expatriate payroll and payment processing

• International pensions

• Global stock option plans

In this chapter, we go through these topics in some detail, from a theoretical and structural point of view as well as from an accounting, finance, and statistics angle. Before we do so, some theoretical and structural issues need to be dealt with.

The Background to International and Expatriate Compensation

When we talk about the overseas staff of a company doing business outside of the country in which their headquarters is located, the composition of the staff can be quite diverse. This company could have

• Headquarters country nationals working in another country, sent from the headquarters country to work there. The employee can be on a temporary or a permanent assignment in the foreign country. Let’s say that the home country is Country A and a Country A employee is being sent to work in Country B. This type of staff in normally called headquarters staff or home-country employees.

• A company could hire an employee from Country C and send that employee to a different foreign country to work. This type of employee will normally be called a third-country national (TCN).

• The company that is setting up operations in a foreign country can hire local nationals in that country. So, if a company is setting up operations in Country B, and if they hire employees who are nationals of Country B (and most certainly they will), these staff members will be called local staff.

These distinctions are critical to the flow of expenses through the accounting system. Clearly, defining the intent of the assignment within the context of the definitions provided here will reduce foreign assignment complications.

Before we go further, it is important to state that in international compensation, the word expatriate refers to employees who are being sent to a different country only for a temporary period of time (and temporary, by its very nature, indicates that it is short term; one to five years). In HR management, the concept of a permanent expatriate is a misnomer. In current practice, this word is often misused, creating confusion and increased expenses.

In expatriate compensation, those employees being sent on an assignment by the company are provided additional (additional to base) allowances, premiums, and payments. All these payments are designed to mitigate the discomforts of uprooting home-country roots and family life temporarily. If an expatriate being paid like an expatriate continues to stay in a foreign location indefinitely, the costs of that assignment will rise, creating a very expensive proposition.

Now let’s set the stage for a detailed analysis of the topics to be discussed. Most companies today do business in countries outside of their home base country or outside the country in which their headquarters is located (that is, outside their country or origin).

The main objective of a global compensation program is the attraction and retention of employees who are qualified for foreign assignments. Then there is the facilitation of the transfer between foreign affiliates, between foreign affiliates and the parent company, and between the parent company and the foreign affiliate. Companies attempt to establish and maintain a consistent and reasonable relationship between the compensation of employees of all affiliates, both at home and abroad. They also have to be concerned with the maintenance of a compensation program that is reasonable in relation to the practices of competitors. This has to be accomplished at optimal costs.

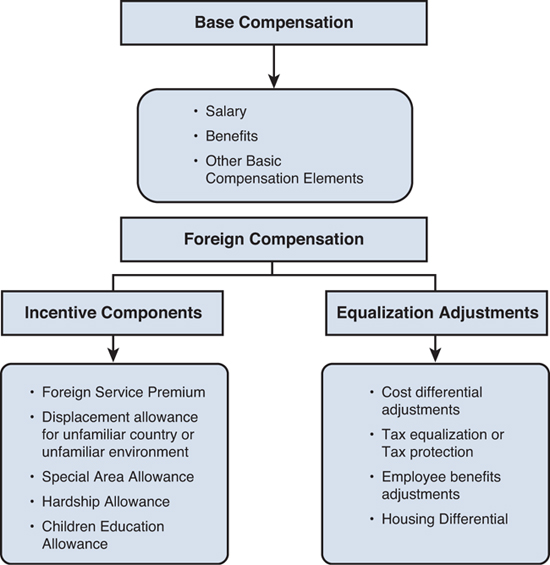

To achieve the objectives stated, additional compensation is provided to employees being sent by the company to work in a different country. The major elements of the additional compensation are as follows:

• Providing an incentive to leave the home country for a foreign assignment.

• The ability to maintain a standard of living that the employee and his/her family are used to in their home country or permanent resident location.

• Consideration is given to career and family requirements that, because of the temporary nature of the assignment, need to be maintained in the home-country location. The idea is that the employee and his or her family will return to the home country when the assignment is completed. The compensation structure is designed to facilitate reentry into the home country at the end of the assignment.

To fulfill these objectives, the determination of individual and organizational pay and benefits on a global basis can become extremely complex. There are many dimensions to consider. The complexities are based on the varying compensation structures from country to country. Salary levels and benefit provisions differ among countries. Complicating the situation further are the issues surrounding multiple currencies and multiple tax laws, processes, and procedures.

Currently, the systems being used in practice are as follows:

• Balance sheet: The balance sheet system is the most prevalent system in use and is discussed in some detail in the next section.

• Lump sum: This system uses the home country’s system for determining base salary. In addition to the base salary, the expatriate is offered a lump sum of money to apply toward the foreign-service expenditures. In this system, it is up to the expatriate to use the lump sum to meet various expenses without intruding on the individual expatriates’ specific expenses.

• Cafeteria: Similar to the lump-sum method, but instead of offering a single sum of money for the foreign assignment, the expatriate is offered a selection of options to choose from. The expatriate can choose which option he or she wants. Options might include a company car, children’s education expenses paid by the company, relocation expenses for household goods, or a country club membership. Limits are imposed on the expenses for each option.

• Negotiation: In this plan, each expatriate employee’s package is negotiated on a one-to-one basis. Companies want to keep things simple. The terms negotiated should be mutually agreeable.

• Regional: Similar terms and conditions offered to expatriates assigned to particular regions. Regional terms and conditions vary from region to region.

• Global pay system: Standardized worldwide terms and conditions are used. No variation exists in the terms and conditions. This system does not allow for much flexibility. Worldwide pay systems, such as job evaluation and performance evaluation, are in use.

• Localization: In this method, the expatriate is essentially paid under the same terms and conditions that exist for local nationals who occupy the same job or position as the expatriate will occupy. This is an appropriate system if the expatriate is being permanently transferred to that location and very little probability of mobility exists for this particular expatriate.

These systems have been widely used in expatriate compensation program planning and administration for many years.

U.S.-based companies use the balance sheet system extensively. There are a very large number of U.S. expatriates working abroad, and because U.S.-based companies prefer to use the balance sheet system, it can be inferred that this system is the most common system.

The Balance Sheet System

The balance sheet system is an effort to ensure that the expatriate employee is “made whole.” That is at a minimum, the expatriate should be no worse off or even better off for accepting an overseas assignment with respect to his or her compensation and benefit terms (see Exhibits 6-1 and 6-2).

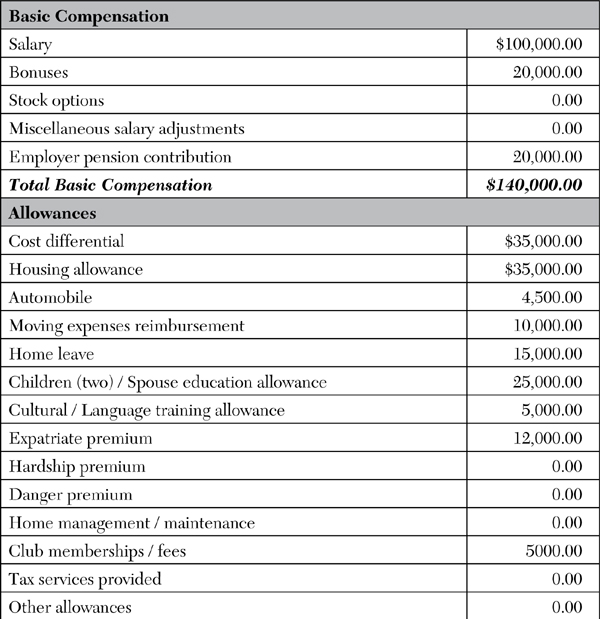

Exhibit 6-1. The Total Compensation Structure for Expatriate Compensation

Exhibit 6-2. A comprehensive list of the possible components is shown.

The balance sheet approach consists of making a balance sheet for the assignment before the assignment begins. This is the approach followed by most U.S. multinationals and is used mostly for senior and middle-level management expatriate employees. The main reason for such an approach is that firms seek to standardize the process. Policies are developed that delineate what is covered and what is not.

We now turn our attention to the incentive and allowance payments normally provided under a balance sheet system.

The Allowance Structure

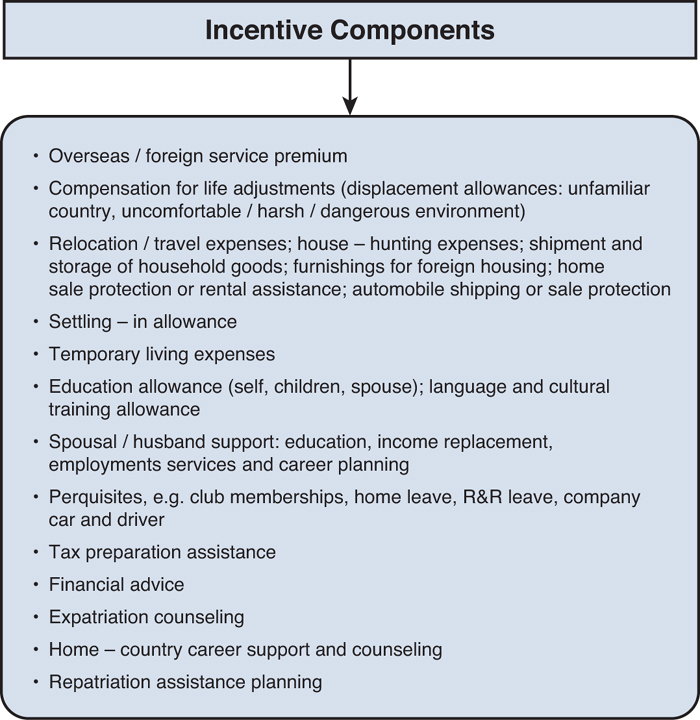

Not every company provides all these components of expatriate compensation. But what follows is a description of all the possible components:

• An overseas or foreign service premium is provided to encourage the employee to take on the foreign assignment. The employee is being asked by the company to take the assignment on behalf of the company. This allowance is provided to encourage the employee to accept the assignment.

An allowance may be provided for lifestyle adjustments. These take the form of a displacement allowance. The displacement allowance is provided for living in an unfamiliar country or in uncomfortable, harsh, and dangerous environments. This allowance is also called a mobility incentive allowance.

• Relocation and travel expenses, house-hunting expenses, shipment and storage of household goods expenses, expenses for acquiring furnishings for the foreign house, temporary rental assistance, and automobile shipping or sale expenses are all reimbursements made by the employing company to the expatriate employee.

The employee and the family would also be reimbursed for temporary living expenses while going to the foreign location and then upon returning to their home base after the assignment is completed.

• The company pays a housing allowance to the expatriate employee. The housing allowance is provided to cover the expenses to acquire a house that is comparable to the house the employee and his family had in their home country. Also, the house needs to be comparable to the employee’s peers in the foreign location. The allowance may also include a utilities allowance.

• An education allowance may also be provided. The education allowance can be for the accompanying spouse and/or children. The education allowance would also include expense reimbursement for language and cultural training for all family members. Other perquisites (for example, club memberships, home leave, R&R leave, company car and driver) are also normally provided.

• Miscellaneous other services are also paid for by the company. These services include tax-preparation assistance, financial advice, expatriation counseling, home-country career support and counseling, and repatriation assistance planning.

• Settling-in allowance is paid to compensate for costs of small items when the expatriate and his/her family relocate, at the beginning and at the end of an assignment. This payment can be made as a fixed payment or as a percentage of home-country gross pay and as a percentage of home-country net pay.

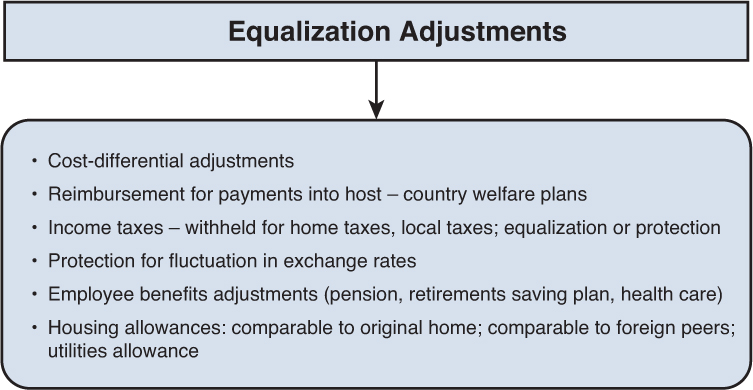

In addition to allowance and incentives, employees being sent to a different country are usually compensated with equalization payments. These payments are designed to ensure that the expatriate employee neither gains nor loses monetarily from the overseas assignment:

• The first equalization payment that is normally provided is a cost-differential adjustment or allowance. This is not a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA). It is a cost-differential allowance. The cost-differential allowance is based on a consulting company’s table. The cost-differential index is applied to a spendable income amount to derive the cost-differential allowance. The calculation of this amount can be quite involved, so we look at its computational details later in the chapter.

• Another equalization payment is the reimbursement for the payments for host or assignment country government-mandated health and welfare plans.

• Yet another equalization payment that has accounting implications is income taxes. These are amounts withheld for home-country taxes and local taxes. The tax obligations are then equalized through either of two methods: tax protection or tax equalization. This topic is further explored later in this chapter.

• Then there are payments for protection against the fluctuation in exchange rates between the two countries (the home country and the assignment country).

• Finally, there is the complex issue of a pension benefit equalization arrangement. This topic is also discussed later.

Looking at the list of compensation payments, you can understand that these amounts can easily add up, creating a large financial burden for the employer. Therefore, it is a very important exercise to budget these expenses carefully before the assignment starts. The budgeting exercise is one of the more important accounting tasks that needs to be undertaken by the HR department. We look at the budgeting exercise in a later section of this chapter.

Note here that the payments and expenses listed and described earlier are not all used in every cross-country assignment. The payments and allowances should be provided only to employees who are being sent by the company for a fixed duration and not for those being hired on a regular or long-term basis. The cross-border transfer is undertaken because there is a specific skill shortage in the country to which the employee is being sent. The employee could also be sent abroad for a fixed duration for training purposes. Payments and allowances are not provided for short-term (less than a year) assignments. Nor are they provided for extended business trips.

Finally, a foreign national employee could be hired or and sent by an employer for regular employment to a different country (direct or regular hires). Those employees are hired for the foreign country operation from a different country on a regular long-term basis. These hires might be provided some temporary payments and allowances for a short while, but they should not be provided all the expatriate allowances and payments described so far.

The Balance Sheet System Explained

A sound expatriate compensation system uses the balance sheet approach. The balance sheet structure is built on the principle that the employee (and his family) being assigned to the foreign assignment should neither gain nor lose financially from the assignment. It also allows planners to design a system that is financially sound from the point of view of managing the expenses within the operational budget guidelines.

The process begins with the employee’s existing compensation in the home country (salary, benefits, and other monetary and nonmonetary remuneration regularly received). Then the two components of (1) the incentives provided to attract and retain employees for the foreign assignment and (2) the equalization components that ensure the expatriate does not suffer from the foreign-country differences in salary and benefits, are added to establish the desired total compensation package for the foreign assignment, as shown in Exhibit 6-3.

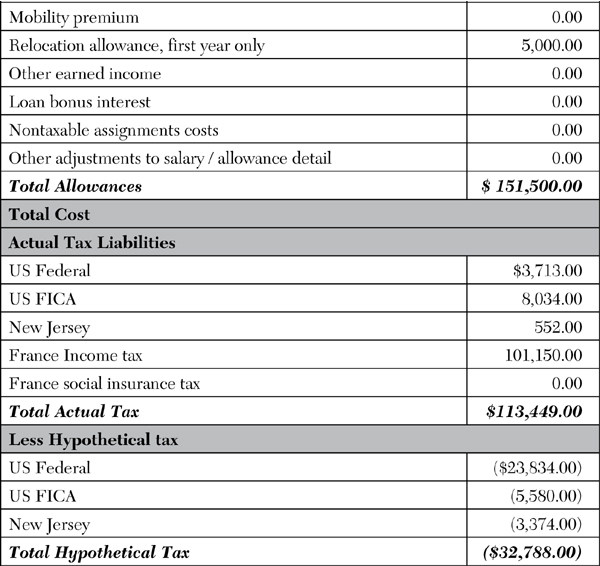

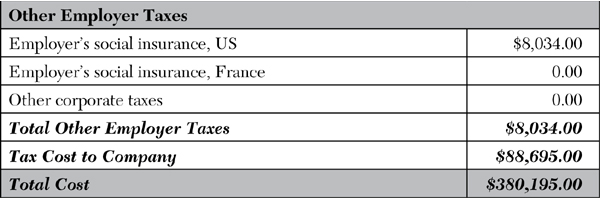

Exhibit 6-3. Example of a Compensation Package for an Expatriate Relocation from New Jersey to Paris, First Year in US Dollars

From this example, an employee who was earning $140,000 at the home location will be earning $380,195 in the foreign location. This is an escalation factor of almost 3. It can get expensive!

Multinational employers also need to address these additional questions when designing global compensation programs:

• Under which country compensation and benefit programs should the employees be covered?

• How will potential gaps in pension and health be covered?

• Is the benefit coverage adequate for all employees?

• Is the benefit package equitable when compared with the benefits of peers in the country of assignment?

• Can coverage under employees’ home-country social programs be maintained as the employee moves around?

During the recent past, with the threats of global economic crisis looming large, companies have had more difficulty ensuring that expatriate employees are paid fair salaries. The achievement of this objective has been made more difficult by rapid currency and inflationary fluctuations. These conditions have created the need to constantly review expatriate salaries. Fluctuating currencies and a wide variety of inflationary patterns across different countries can create differences in the amount of salary received and thus impact the expatriate employee’s purchasing power (positively or negatively) within very short time periods. One way to approach this challenge is to convert a spendable percentage (typically 60%) of the expatriate’s salary into the host-country currency on a monthly basis. The other way is to provide direct reimbursements for benefits such as accommodation, transportation, and the education of children.

The spendable percentage leads to a spendable income. This is the amount that the expatriate’s counterpart in the same location at the same salary level and family size spends for goods and services in their home country. This is the portion of base salary that is typically spent on goods and services on a daily basis. This amount varies by family size and income level.

A concluding point with respect to the balance sheet system is the issue of stated and paid amounts. In many cases, the pay terms and conditions are stated in a certain currency, but actual payment occurs with another currency. Sometimes total payment is split into two payrolls: one payment coming from the home-country payroll, and another portion being paid by the host-country payroll system. Therefore, it is critical that the pay method be clearly understood and accepted by all parties involved. Actual practice with regard to the quotation and delivery of pay varies.

Some companies quote net assignment cash pay to the expatriate. Others deliver home gross pay plus allowances with a guarantee of net pay. Yet others quote gross assignment pay, and in a small percentage of companies the approach varies from country to country.

Expatriate Taxes

Now let’s look at the tax accounting issues affecting expatriate employment. Two structural policy formulations exist: tax equalization and tax protection.

Tax Protection

If additional taxes result from the foreign assignment, the employee is “protected” from those additional taxes. And if the taxes are lower than what the employee paid at home, the expatriate employee can take that benefit as a windfall. This might happen if the employee goes from a high-tax country to a low-tax country or a no-tax country. So, employees might pay less in tax than what they were paying but never more than what they paid in their home country. Tax protection is not a common policy.

Tax Equalization

In this policy, expatriates are “equalized” so that they pay the same amount of tax as they paid in their home country before their departure to the foreign assignment. They pay no more or no less in taxes from what they would have paid if they were still in their home-country assignment. If there are additional taxes as a result of the foreign assignment the employing company pays. At the same time, the company also benefits if the foreign assignment taxes are less than what the employee had to pay at home. It is believed that this policy is fair to everyone concerned because the employee’s obligation remains the same as they were before the foreign assignment–that is the same amount of tax as if they were still in their home-country assignment.

Tax Equalization Explained

Tax equalization is applied when employees are transferred to a country outside of their home country. Again, the basic concept of the policy is that an individual employee will pay no more or no less taxes than he or she would have paid if they had not been sent on the expatriate assignment.

A tax equalization policy must initially take into account what income will be covered. An expatriate policy normally indicates whether (in addition to salary and bonuses) stock option exercises, restricted stock earn outs, interest, dividends, capital gains, and the spouse’s income will be equalized.

Personal exemptions and deductions are taken into account, even if they differ from home-country deductions. This can get tricky. Suppose while at home an expatriate was taking a mortgage and other principal residence-allowable deductions. Because of the expatriation, the employee sold his home. So would the tax equalization policy take into account the fact that the expatriate’s home-country taxes were significantly reduced before the assignment because of the principal residence deductions and now they are not going to be able to take these deductions? Because of this contingency, most companies require employees to maintain their home-country principal residence and rent it out during their expatriate assignment. The company might also pay property-management fees to facilitate renting of the home. But the question still remains if the employee does sell the house whether the tax equalization policy calculates home-country tax obligation with or without the principal residence deductions. The expatriate tax policy for most companies would clearly address these and other issues. Therefore, the tax equalization policy can be lengthy, because it must attempt to account for every contingency that could be encountered in the foreign assignment.

At the planning stages of an assignment, a tax specialist, whether internal or external, computes the amount of tax an individual would have paid had he or she not been sent on the expatriate foreign assignment. This is a hypothetical calculation, and as such it is commonly referred to as the hypothetical tax or hypo tax.

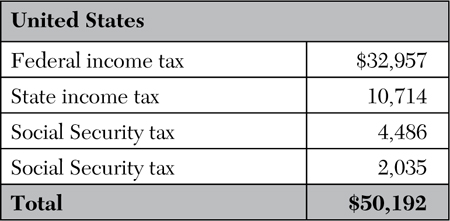

Let’s take an example of a married couple, where the husband is the employee and is an engineer. The couple has no children, and they currently live and work in San Francisco. Let’s say they rent an apartment in downtown San Francisco at a cost of $3,000 a month. The engineer’s current compensation is $150,000, and the employer has asked him to relocate to Abu Dhabi on January 1, 2014. Note that according to the expatriate policy the spouse’s income is being excluded from the hypothetical calculation. For this example, we are assuming that the spouse is a working professional and is not planning to accompany her husband because she does not want to give up her job. Also note that the company will use the standard tax deduction for one individual and calculate the hypothetical tax based on a filing status of a single tax payer. The specific path chosen for this situation is simply because of the facts for this expatriate employee. The employee is being sent on a single-status assignment because of the spouse’s employment situation. The hypothetical tax would be as shown in Exhibit 6-4.

Exhibit 6-4. Hypothetical Tax Calculation

The $50,192 will be deducted from the employee’s gross compensation, and the employee will receive a net compensation of $99,208 plus allowances such as housing, cost-differential allowance, home leave, and so on based on the terms of the overseas assignment. The employer now is responsible for paying all U.S. and foreign income and social taxes on behalf of the employee. In this case, the employer might gain because the U.S. taxes on $99,208 will be lower and because there are no Abu Dhabi taxes. The matter is slightly more complex than stated so far. This is because the employee’s actual tax obligation will be based on a married filing jointly status. So, the company most likely will pay a tax consultant to prepare and file the couple’s actual taxes. When the tax consultant calculates the actual married filing jointly obligation, the consultant will do resolution calculation as shown here.

Married filing jointly obligation minus tax obligation on single status income of $99,208 equals additional (if any) employee required payment. In this case, the company might actually pay the taxing authorities the married filing jointly obligation and require the employee to reimburse the company if there is any difference.

Tax Protection Explained

Only a few differences exist between tax protection and tax equalization policies.

The first difference is that if the actual tax burden of the expatriate employee on a worldwide basis is less than the tax obligation the expatriate employee had in his or her home country before the assignment started, the employee can retain that benefit.

The second difference is that under tax protection, no hypothetical tax withholding is taken from the expatriate employee’s pay.

The third difference is that unlike tax equalization the expatriate employees will themselves pay both their home-country tax obligations and the country-of-assignment tax obligations.

After the expatriate employee tax obligations are paid, the company makes a tax protection calculation. If the tax obligation both to their home countries and their destination country paid directly by the employees is more than what they would have paid before the assignment started in their home country, the employing company reimburses the employee directly for that amount. This might create a tax windfall for the employee.

For various reasons, tax protection policies are not very common. The major reason is that the expatriate employees would not want to pay the tax obligations directly and have a major impact on their personal cash flow situations.

Tax Gross-Up

As indicated under a tax protection policy, the company reimburses the employee the difference between what they pay in taxes during the foreign assignment and what they would have paid had they not gone abroad. However, that amount now becomes income to the employee, which then becomes taxable income to the employee. We then have a tax-on-tax situation. This is where the tax gross-up calculations come in.

The gross-up calculation will become an iterative calculation to determine the amount needed to be paid to the employee so that in effect the expatriate employee will receive the tax protection payment on a tax-free basis. The gross-up calculation is not limited to the tax protection payment; it also applies to all other tax payments the company makes on behalf of the expatriate employee while he or she is on the foreign assignment.

The Actual Tax Calculation

When the expatriate’s actual tax return has to be prepared and filed, the company will engage a tax consultant or a tax specialist to complete and file the return on behalf of the employee. When the expatriate is sent to a country where there is a local country tax obligation, the company will usually engage a tax consulting company with multicountry operations so that both the home country and the local tax obligations are properly calculated and proper tax credits are taken. (Often there are tax agreements between countries stipulating tax credits.)

The Applicable Tax Provisions

Next we provide a summary of the tax provisions that apply to U.S. citizens and permanent residents living and working in a foreign country.

A U.S. expatriate policy applies to a citizen or resident of the United States who lives outside the United States for more than one year. U.S. citizens or permanent residents on business trips lasting up to one year or more must also consider the U.S. and foreign tax consequences related to that long-duration business trip.

U.S. citizens and residents must report 100% of their worldwide income on their U.S. individual income tax return, regardless of where they live and regardless of where the income is paid. Therefore, U.S. expatriates must continue to file U.S. tax returns and in many cases owe U.S. tax during their foreign assignments. U.S. expatriates take advantage of two special tax provisions to reduce their federal income tax liability while on a foreign assignment. These provisions are: foreign tax credit and exclusions from income.

Foreign Tax Credit

The foreign tax credit can reduce U.S. federal and the state individual income tax. The foreign tax credit is designed to help reduce the double taxation of income. So, if the expatriate has a foreign tax obligation for income earned in that foreign country, the amount paid to that foreign tax jurisdiction offsets the U.S. income subject to U.S. tax. This is called the foreign tax credit.

Exclusions from Income

A U.S. citizen or resident who establishes a tax residence in a foreign country and who meets either the bona fide residence test or the physical presence test may elect to exclude two items from gross income:

• Foreign earned income exclusion in 2011 is up to $92,900. This is a straight exclusion of foreign source income in the determination of taxable income.

And

• For the foreign housing exclusion, the current IRS regulation states,1

The housing exclusion applies only to amounts considered paid for with employer-provided amounts, which includes any amounts paid to you or paid or incurred on your behalf by your employer that are taxable foreign earned income to you for the year (without regard to the foreign earned income exclusion). The housing deduction applies only to amounts paid for with self-employment earnings.

Your housing amount is the total of your housing expenses for the year minus the base housing amount. The computation of the base housing amount (line 32 of Form 2555) is tied to the maximum foreign earned income exclusion. The amount is 16% of the maximum exclusion amount (computed on a daily basis), multiplied by the number of days in your qualifying period that fall within your tax year.

Housing expenses include your reasonable expenses actually paid or incurred for housing in a foreign country for you and (if they lived with you) for your spouse and dependents. Consider only housing expenses for the part of the year that you qualify for the foreign earned income exclusion. Housing expenses do not include expenses that are lavish or extravagant under the circumstances, the cost of buying property, purchased furniture or accessories, and improvements and other expenses that increase the value or appreciably prolong the life of your property. You also cannot include in housing expenses the value of meals or lodging that you exclude from gross income (under the rules for the exclusion of meals and lodging), or that you deduct as moving expenses.

Also, for purposes of determining the foreign housing exclusion or deduction, your housing expenses eligible to be considered in calculating the housing cost amount may not exceed a certain limit. The limit on housing expenses is generally 30% of the maximum foreign earned income exclusion, but it may vary depending upon the location in which you incur housing expenses. The limit on housing expenses is computed using the company’s worksheet.

Additionally, foreign housing expenses may not exceed your total foreign earned income for the taxable year. Your foreign housing deduction cannot be more than your foreign earned income less the total of your (1) foreign earned income exclusion, plus (2) your housing exclusion.

Other U.S. Tax Issues

In addition to the special tax provisions that apply to U.S. expatriates, an expatriate is still subject to the normal U.S. tax laws with respect to all other items of income, expenses, and credits. Other common federal tax issues that arise due to a foreign assignment include the following:

• Treatment of employer-provided allowances and reimbursements

• Moving expenses

• Rental of principal residence

• Sale of principal residence

• Short-term versus long-term assignments

• Social Security taxes

This review has provided an overview of the tax calculation structures of U.S. citizens living and working abroad. The actual specifics of each taxpayer will vary based on each individual’s tax filing status, exemptions, and standard or itemized deductions. Other implications on an individual tax obligation will be determined by that individual expatriate’s investments and many other tax factors.

The Cost-Differential Allowance

Of the many allowances that expatriate employees are provided while on a foreign assignment, the allowance that requires the most technical understanding is the cost-differential allowance.

In practice, the cost-differential allowance is called by various names: goods and services differential, commodities and services allowance, cost-of-living index, and COLA (cost-of-living allowance). The last two designations are not quite correct, as you will understand from this discussion. The meaning of all these terms is the additional money needed to maintain a similar standard of living as was enjoyed by expatriates and their families in the home location. This difference may arise because of cost differences and living-pattern changes between the home and the foreign locations. This is not a cost-of-living allowance. It is a cost-differential allowance. The cost-of-living allowance is based on a time period-to-time period index. The time-to-time index is one of the measures that are normally used to calculate the inflation rate in macroeconomics. The cost-differential allowance is based on a place-to-place index. The basic idea is that the expatriate and his or her family enjoyed a certain market basket of goods and services in his or her home-country location. This market basket of goods and services cost the expatriate employees a certain percentage of their income (called spendable income). Under the balance sheet philosophy of compensation, the company wants the expatriate employee to neither gain nor lose from accepting the company-initiated assignment. So, the company relies on a place-to-place price-differential index for the same market basket of goods and services that the expatriate employee was using while in his or her home location. Then the company applies that index to a spendable income, which results in a cost-differential allowance amount. The cost-differential allowance is then paid to the employee on a regular basis. With this allowance, the employee and his or her family can buy and enjoy the same market basket of goods and services in the foreign location. So, they neither gain nor lose vis-à-vis their home-country standard of living.

Of course, all these calculations are based on average prices. Because there is no “average expatriate employee,” the cost-differential allowance in reality can be either sufficient or not for any particular expatriate employee.

Let’s look at the cost-differential allowance calculation methodologies.

Various data services companies (Organization Resources’ Council, AIRINC, and INCOMP) research and compute the place-to-place indices. In addition to the consulting companies, the U.S. State Department also calculates and publishes cost-differential indices covering various cities around the world. The State Department does these computations for the use of its various foreign stations to adequately compensate foreign-service employees.

The consulting companies normally conduct a consumer income and expenditure survey every few years. These surveys result in a series of data tables (that is, spendable income in different cities around the world sorted by base salary levels). The spendable income is a number that includes all costs for food at home, food away from home, tobacco and alcohol, clothing, medical expenses, transportation (excluding car-purchase payments), recreation, personal care, household furnishings and operation, domestic services, and miscellaneous expenses. This data is collected from expatriates or their sponsor (if located in the foreign jurisdiction).

The surveys indicate that for a given income level, the percentage spent by a standard family for goods and services may vary depending on the local conditions.

The consulting companies in this manner calculate the spendable income and spendable income percentages for a variety of cities around the world. The collected data also determines the spending situation (availability and ease of purchase) in that particular city. In some cities, most goods and services are readily available, and in others they are not. The survey delineates the ease of purchase in each of the cities surveyed. In London, it is possible to buy nearly anything at a comparatively reasonable price. So, the percentage of income spent locally for goods and services is relatively high in London and in similar cities having well-established and well-stocked markets. In remote areas, however, the availability of clothing, medical care, recreation, and so on is quite limited. The expatriate employees will tend to defer these purchases until they go on home leave. Therefore, they spend a higher percentage of income in the United States, and they spend a smaller amount in the foreign location.

The consulting companies, after establishing the spendable income levels for various cities, then assign them to one of three categories: maximum loading, standard loading, and minimum loading. The designation depends on the availability of goods and services and the estimated required expenditures in that city.

From the results of the consumer income and expenditure survey, the consulting companies report spendable income levels separated into the three different loading levels. In other words, they average out the data from the survey into the three categories (maximum, standard, minimum). After that, further sorting of the data occurs. The spendable income level is then reported by family size. Finally, the data is reported to clients, by loading factors, by six family sizes, and by income level.

Cost-differential indices assume the home country has an index of 100. All foreign-assignment locations are measured relative to this base. An index above 100 indicates that the cost of living in the foreign-assignment country is higher than the cost of living in the home country. If the index is below 100, the cost of living in the foreign location country is lower. If the foreign-assignment location city has an index of 110, this means the relative cost of living in that city is 10% more expensive than the home location. In contrast, an index of 95 implies that the host city is 5% cheaper than the home location.

Then, the calculated index is multiplied into the spendable income level for a particular city and by the indicated loading factor assigned to that foreign location.

If the spendable income is $60,000 a year and the index is 110, the allowance is computed as 0.1 × $60,000 = $6,000. The expatriate employee will be given an allowance of $6,000 a year to cover the additional costs for goods and services in that foreign location.2

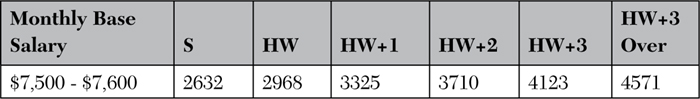

Exhibit 6-5 gives an example of the survey data presentation.

Exhibit 6-5. Survey data presentation

The consulting companies report the collected data in the format shown.

So, let’s say the cost-differential index for this location is 111.25 and the expatriate employee is on an HW +2 family assignment and the expatriate employee’s monthly base salary is $7,545. In that case, the employee’s monthly cost-differential allowance is $3,710 × .1125 = $417.37.

Currency Fluctuations

Expatriate employees are also faced with the challenge of managing multiple currencies. Currency fluctuation can have an impact on the buying power of the expatriate’s income. The expatriate faces two challenges: transferring money from home base to the foreign assignment location and paying required bills across countries. Remember that the expatriate employee invariably needs to pay bills in the home country, to continue a lifestyle that will allow the expatriate to return home after the assignment without having to start all over again.

To mitigate the currency-fluctuation issues, companies usually take the following actions:

• Split-payment arrangements: Many companies pay the employee a certain percentage of income in the host country itself (and in the host country’s currency). The rest of the income is paid in the home-country currency. This way the expatriate has appropriate currency funds in both home and host countries without experiencing currency fluctuations. In actuality, the corporate practice in this regard varies. Surveys indicate that the practice is distributed among (1) payment in home country, (2) host-country currency, (3) depends on the home and host location, (4) paying everything in a reference currency and (5) paying part of the salary in a reference currency.

In companies that engage in split-payment policies, the split formula becomes important. Surveys indicate that actual practice involves (1) paying a savings part in home-country currency, (2) leaving the choice up to the expatriate, and (3) paying a certain percentage of the host-country salary in the host-country currency.

Companies also employ a policy to adjust the expatriate’s salary to mitigate the effects of currency fluctuations. Practice among companies here is also varied. Company policy in this regard includes (1) no adjustments for currency fluctuations during assignment, (2) making an adjustment every year, (3) making adjustments every six months, (4) making an adjustment when the currency devaluates by more than a certain percentage, and (5) making adjustments on a case-by-case basis.

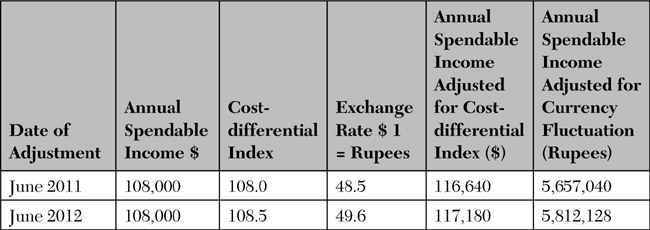

• Adjust the cost-differential allowance for currency fluctuations: We have explained in the cost-differential section of this chapter how the cost-differential allowance is calculated. We have shown that the various consulting companies establish spendable income levels by family size and income levels in various countries. We have also shown that the spendable income levels are modified by a goods and services loading factor. Now we show that the cost differential can be further adjusted for currency fluctuations. To demonstrate this adjustment calculation, let’s use an example of an expatriate with a spouse and two children moving from New York to Mumbai, India.

The company expatriating this employee will complete the calculation shown in Exhibit 6-6.

Exhibit 6-6. Currency Adjustments to the Cost-Differential Allowance

Using this calculation, the company ensures that the expatriate and his/her family moving from New York to Mumbai is kept whole for (1) purchasing power and (2) a cost-differential allowance that is stable in the host location (Mumbai) for a currency fluctuation.

Global Payroll Systems

The laws that regulate HR labor practices and payroll procedures vary from country to country. There are specific requirements to comply with, pay-frequency timings, pay and work rules, and tax. For example, in Italy, taxes must be paid at the country, regional, and local levels and need to be submitted by the deadlines as established by the law. It does not matter how many employees are employed; compliance with the laws is mandatory. In addition, different data privacy and cross-border data-transfer laws further complicate the implementation.

Payroll is not only affected by local laws but also by languages, currencies, and time zones. A U.K. company based in China cannot provide its Chinese employees with pay notices in English or pay them in British pound sterling. Chinese employees must be paid on time, in the local currency, and documented in Chinese.

Cultural differences exist, as well. In different countries, employees are accustomed to different payment methods. For example, although employees in many countries expect direct deposit, those in the Netherlands might prefer paper verification, whereas employees in the Middle East might prefer electronic verification. In Russia, Mexico, and Brazil, paper pay notices are customary.

In other cases, past practices create precedents that cannot easily be changed. For example, German Works Councils maintain great influence over the payroll process and other aspects of labor and personnel practices on job sites. And the Works Council has to be consulted on any and every HR and payroll policy and practice issue.

Global payroll systems will need to cover different country-of-origin expatriate employees and local national employees. In large global construction projects, like those undertaken in the Middle East, employees are sourced from as many as 30 countries. The payroll system has to work with the specific tax-related compensation policies from all these separate employment entities. It also has to cope with the movement of salaries and tax distributions across the world in different currencies. There are also country-specific payroll regulations that need to be adhered to. Accounts with reputable international banks need to be managed to make rapid, mistake-free funds transfers and payments.

In many European countries, vacation and sick leave must be tracked as part of the payroll process. In France, failure to do so will likely mean that upon termination the labor courts will rule that no vacation has been taken, and a full payout to compensate may be required. In Italy, it is necessary to accrue a mandatory severance payment each month, which can create challenges in payroll accounting. In many countries, the additional 13th- and 14th-month holiday payments or bonuses have to be paid at certain times within the year. In the Netherlands, it is necessary to account for mandatory medical insurance contributions through the payroll process.

Payroll processes also have to contend with other forms of compensation, such as stock-based compensation schemes, stock options, and stock grants. These programs require coordination between the parent and local entity to ensure that grants/exercises are correctly captured for reporting purposes and that any taxation related to the compensation is correctly withheld and within required time frames. Sometimes employees will want their salaries adjusted to take into account these country-specific transactions, which means finance and HR professionals should be clear on the payroll processes. Proper payroll accounting and processing becomes crucial in the effort to reduce employee complaints and disputes. Operational logistics that span many locations, cultures, currencies, languages, and laws can add levels of complication. Fortunately, these can be addressed and streamlined.

Therefore, global HR and payroll professionals need to be skilled enough to understand and manage the many vagaries of an international payroll system.

With payroll processes so complex and country specific, U.S.-based companies first turn to their U.S. payroll provider for advice and assistance. Some of these providers can offer services in certain countries, but not all countries. Many of these providers are not willing to provide such services unless the number of employees is large enough for them to make the financial commitment to provide the services.

Other companies attempt to manage global payroll in-house. This will require that the staff in both IT and payroll departments need to be experts who understand the complexities associated with all the company’s various locations. Hiring the right skilled staff might prove very difficult. When implemented completely in-house, solutions can lead to an increased risk of error. In-house solutions and implementations can lead to employee dissatisfaction and possible legal problems.

More commonly attempted is a local solution, where payroll is managed with different vendors in each country. Although this method helps address concerns surrounding local cultures, languages, currencies, and regulations, it can prove costly and difficult to manage. In this solution, local employees are tasked with managing the individual vendors. Because payroll systems are maintained within each country, consolidations are time-consuming, with information generated by the various local payroll systems not being consistent in many ways. This makes consolidated payroll and accounting reporting an onerous task.

The most effective alternative then becomes using a consolidated global payroll platform. A global software-based payroll platform can reduce costs, automate reporting, facilitate compliance, and improve financial control. However, it can also be intimidating. The answer lies in selecting the right technology and the right vendor.

For companies where the return on investment (ROI) in these complex software-based platforms is not justifiable, the viable option is outsourcing to a reputable third-party administrator. Whether acquired for in-house use or for use by a third-party administrator, the global software platform should have modules that include payroll accounting, social insurance, travel-expenses administration, incentive compensation, posting to accounting ledgers and journals, entity funding mechanisms, statutory (compulsory) benefits, and tax withholding and reporting requirements. Note that these provisions will vary widely from one country to another. The chosen software must also assist the company to track complicated leave formulas and understand local employment requirements and expectations. They must also be able to file health and welfare documentation.

In addition to an adequate software platform, the international payroll provider who uses the chosen software platform should be able to advise and assist with all the mandatory activities that go along with supporting international and local payrolls, including the following:

• Entity setup: The payroll provider should be able to advice which entity type is best for the specific company and assist with the setup of the entity.

• Registration of tax and social programs: Once the appropriate entity has been identified and the registration setup completed, there could be follow-on registrations required to support a locally compliant payroll.

• Benefits: The provider should be able to advice on structuring mandatory benefits and health and welfare programs. The provider should also advice as to the best way to accrue and account for leaves and vacations in accordance with the country’s rules and regulations, commensurate with the company’s accounting procedures and processes.

International Pensions

As you have seen in this chapter, the expatriation of employees abroad is a fairly complex matter. The assignment comes entangled with accounting, finance, legal, tax, and HR issues. You have seen that many issues need to be resolved:

• Which Social Security system will the expatriate remain in?

• Where will the Social Security contributions be made?

• Where, when, and how the tax obligations of the expatriate will be dispensed.

The answers to these questions depend on specific terms and intentions of the assignment.

But still remaining is the very important question as to the status of the employee with respect to the company’s pension benefits. There are legal and tax concerns attached to the issue.

Under these circumstances, organizations have various paths that they can take with respect to the expatriate’s pension benefits. (We are assuming here that the employee was participating in the company’s defined-benefit pension plan before the expatriate assignment commenced.) Note that we devote an entire chapter on pension accounting. Here we are simply talking about ensuring the protection of the expatriate’s pension rights while on a foreign assignment.

Companies have four options:

• Keep the expatriate in the home country’s defined benefit pension plan.

• Switch and enroll the expatriate into the host-country pension scheme while he or she is on the foreign assignment.

• Established a top-up pension arrangement that is run in conjunction with the home-country or host-country pension plan.

• Set up a completely separate offshore pension plan. The participants of this plan will be expatriates. The assumption here is that the organization setting up such a plan has a cadre of internationally mobile expatriates who will continue on an expatriate career path for long periods. Companies setting up such a plan are those that deal with expatriates who are regarded as permanent transferees who are unwilling to move to their home-country pension plans.

A PricewaterhouseCoopers survey in 1999 found that 85% of permanent expatriates join the host-country pension plan. And 90% of fixed period expatriates remain in the home-country pension plan. Top-up offshore plans are rare.3

Companies setting up top-up offshore plans should be aware of the following issues:4

• Compliance with home-country and host-country employment laws and regulations.

• Coordination of benefits between home and host plans that the expatriate has participated and will participate in. These terms can be vesting requirements, integration of defined pension formulas, and government-sponsored Social Security plans (offsets) the expatriate has contributed to.

• Government-dictated pension guarantees triggers in case of plan dissolution. Unfunded top-up plans usually do not provide the participant any guarantees.

• Currency fluctuations.

• Impact of benefit taxation and the deductibility of employer contributions.

All of these complex issues make a top-up offshore unfunded pension plan for permanent expatriates and third-country nationals highly infeasible.

Global Stock Option Plans

The worldwide business community is recognizing the advantages of sharing equity with employees. Rewarding employees with stock options or other equity-based compensation is a common practice in the United States. Emulating this practice, multinational corporations are increasingly extending these plans to employees in other countries. Companies that want to expand these programs to other countries must understand that they face unfamiliar securities, tax, and accounting laws.5

There are various forms of stock-based compensation programs: stock options, restricted stock, restricted stock units, stock appreciation rights, performance shares, and stock purchase plans. The type of award offered and the way the stock plan is designed are two primary factors that affect legal compliance issues in different countries.

Local tax laws dictate the form of equity compensation to be used in a country. For example, restricted stock awards have become popular in the United States. In other countries, restricted stock awards are not as common. In countries where such awards are taxed at the time of grant, there can be an unfavorable tax outcome. Restricted stock units may be a better choice under those circumstances. Other foreign tax laws may also result in awards being taxed prior to the employee’s receipt of all or a portion of the award. It is important to understand the international tax implications for all aspects of proposed stock-based plan awards.

Tax rules in some countries provide tax advantages for certain qualifying stock-based arrangements. These arrangements are subject to restrictions as to eligibility, holding requirements, and grant limitations. The tax benefits offered will ultimately have to be judged based on other mitigating factors.

The country-specific securities laws are another complicating factor in the selection of the appropriate stock-based compensation program. Stock registration and the publication of prospectus may apply when stock-based plans are implemented. This might require that the proposed plan be customized to qualify for an exemption. In the absence of an exemption, publishing the required prospectus can be time-consuming and cost prohibitive.

Implementing equity-based incentive plans in countries with strict exchange-control regulations can be especially challenging and will often require customizing a plan for use in the country. In addition, employment law considerations might apply, and these might include (1) taking steps to reduce the risk that equity compensation will be regarded as a part of contractually promised compensation and (2) understanding the impact of awards on employees’ compensation with respect to governmental requirements and other employee benefit programs.

Another issue is the enforceability of the award agreement provisions. Two areas to highlight in this regard are restrictive covenants (such as noncompetition and nonsolicitation clauses) and recoupment (or clawback) provisions.

Plan administrative practices need to be considered prior to the issuing of awards in each jurisdiction. And these practices are (1) tax-withholding requirements, (2) filing and reporting obligations, (3) payroll and accounting information flow, and (4) data-privacy compliance.

Cross-border equity grants give rise to special administrative issues. For example, plans having a sell-to-cover feature for tax withholding (where a portion of the shares issued are sold to cover the employer’s withholding obligation) in foreign jurisdictions can be complicated by fluctuating currency exchange rates and sales restrictions under local securities laws.

Other considerations are the proper allocation of equity plan expenses and the availability of corresponding deductions between the parent issuing company and the local subsidiary employer. Chargeback agreements are often used to deal with expense allocation, exchange control, and stamp-duty matters.

The mobility of today’s workforce across international boundaries raises further issues for the design and administration of stock-based compensation plans. As individuals transfer from one tax regime to another, they may be at risk of incurring double taxation or other adverse consequences. Implementing effective monitoring procedures, whether managed internally or in coordination with third-party service providers, can help companies meet these challenges. It is important to keep up-to-date on developments in the relevant laws in each jurisdiction in which awards are or may be granted. Regular compliance reviews are an important responsibility of global equity plan sponsors.

Companies also face nonlegal challenges when expanding their equity-based compensation plans to employees overseas. Finding appropriate compensation surveys to benchmark per person award grants can be difficult. Reliable surveys with comparison data on which to base these decisions are not readily available. Compensation comparisons across jurisdictions are complicated by fluctuating exchange rates and disparate wage and cost-of-living rates.

Cultural factors should also be considered. Employees in countries where equity-based compensation is rare may be uncomfortable or suspicious of noncash remuneration. A clear communication program is key to successful introduction of a plan granting unfamiliar types of awards or having complicated design features. Note also that translation of some plan-related documents may be required.

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Expatriate compensation systems

• The balance sheet system

• Foreign service premium

• Housing allowance

• Education allowance

• Cost-differential allowance

• Expatriate taxes

• Tax equalization

• Tax protection

• Tax gross-up calculation

• Foreign Tax Credit

• Spendable income

• Global payroll systems

• International pensions

• Global stock option plans