1. Setting the Stage

Aims and objectives of this chapter:

• Set the stage for the discussions in the book

• Address the concept of employee benefits

• Present various categories of employee benefits

• Discuss the employee benefit environment

• Discuss the strategic considerations in designing employee benefit programs

• Explain the integrated system approach to plan employee benefits

• Discuss the cost dimension of employee benefits

At their inception, employee benefits were considered “fringe benefits,” a mere afterthought to cash wages. Employers who were concerned about their employees’ welfare, of their own accord, handed out “fringes” to them. As time has gone by, however, these benefits have evolved into a significant portion of a worker’s total official compensation package, sometimes making up as much as 35% or more.

In their book Compensation, authors Milkovich, Newman, and Gerhart provide their definition of employee benefits within a total employee compensation package as “all forms of financial returns and tangible services and benefits employees receive as part of an employment relationship.”1

1 Milkovich, George T., Jerry M. Newman, and Barry A. Gerhart. Compensation, 10th Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin, 2011, p. 10.

Others have offered separate definitions for employee benefits, including programs financed by employers that cover situations such as death, accidents, sickness, retirement, or employment.

A broader definition states that employee benefits include all services outside of cash wages, received by a worker from their employer directly or through outside agencies.

The broadest categorization of benefits, therefore, would resemble the following list:2

2 Beam, Burton T., Jr., and John J. McFadden. Employee Benefits, 9th Edition, Ed. Karen Stefano. Dearborn, A Kaplan Real Estate Education Company, 2012.

1. Legally required governmental programs

a. Social Security

b. Medicare

c. Unemployment compensation

d. Workers’ compensation

e. Temporary disability insurance

2. Company-sponsored loss-exposure insurance and retirement benefits

a. Death

b. Disability

c. Long-term care protection

d. Medical care

e. Dental benefits

f. Group Legal benefits

g. Property and liability insurance

3. Payment for time not worked

a. Vacation

b. Holidays

d. Maternity/paternity leave

e. Reserve/National Guard duty

f. Military leave

4. Additional cash payments

a. Educational assistance

b. Moving expenses

c. Suggestion awards

d. Christmas bonuses

5. Additional services

a. Subsidized cafeterias

b. Employee discounts

c. Wellness programs

d. Employee assistance programs

e. Daycare services

f. Adoption assistance

g. Financial planning assistance

h. Retirement counseling

i. Free parking

Functional Categories of Employee Benefits

The categorization laid out in the preceding list is too broad and covers many items and services that are not within the purview of this book. However, you can see that employee benefits cover many individual plans, as outlined.

The broader categories of these plans can be grouped as follows:

1. Legally mandated plans such as Social Security and other government programs

2. Private plans sponsored by employers, either exclusively paid for by employers or fully/partially paid by employees

3. Employee services—programs provided to assist with employees’ life conveniences (for example, employee cafeterias, purchase discounts, childcare, education assistance, and the like)

4. Payments for time not worked, such as paid rest, sick leave, maternal/paternal leave, and vacation time, among others

This book focuses primarily on the second category of benefits (private plans sponsored by employers) because the bulk of expenses rests in this category. This book covers the accounting, finances, and related subject matter, as delineated in the preface.

The Employee Benefits Environment

Over the past hundred years, significant, pervasive, and comprehensive changes in the field of employee benefits have occurred. Shifts in society, technology, politics, economy, business, and management have all contributed to these changes.

Changes in Society

With the advent of the industrial revolution, while businesses remained primarily self-sufficient and family owned, there was a movement from small, rural, agricultural enterprises to craft-based enterprises. In this environment, workers who were not relatives of the owners were rarely employed.

Further changes occurred with the introduction of manufacturing. Work-seekers moved from rural environments to urban. Gone were familial protections available in rural settings. Most workers’—and their families’—living needs had to be purchased.

Moreover, the safety nets commonly found in rural settings did not exist in this environment; workers required a voice, and they demanded better working conditions as well as job security benefits. Owners were now dependent on these workers—many of whom were skilled craftsman—whose efforts directly tied to the success of their employers. The voice of employees, with regard to their working conditions, increased alongside their skills and knowledge. In other words, because employers needed these skilled workers, the demands increased.

New employers found that they were required to provide benefits to improve their workers’ living conditions; therefore, employee benefits became an official and equal part of employee compensation systems, instead of a fringe that was dependent purely on goodwill and generosity of the employer. In this way, the industrial revolution ushered in an era of improved living conditions, increased life expectancies, and an enhanced quality of life for the workforce.

Along with these changes in the workplace, there was a growing clamor from religious and philanthropic entities, which challenged employers to further improve the lives of the working class. This resulted in demands for healthcare protections and other social insurance schema. Directly alongside this, employers also noticed pressure for similar protections from politicians whose constituents were either older people or the unemployed. As a reaction to these continued pressures, and also to avoid governmental interventions, employers opted to introduce these protection benefits themselves.

Changes in Management

With these significant changes occurring in the social environment, the field of management was also directly affected. Management as a specific science/art evolved, and there was a priority shift from simple process efficiency to worker effectiveness. Employers’ benevolent concerns for their workers increased, irrespective of whether their motives were altruistic or simply an attempt to ward off governmental intervention. What began as a concern over employee welfare evolved into workforce demands. Unions played a large part in this transformation. Some employers began providing pension benefits in an attempt to streamline, or else reduce, their workforces. This also happened as a result of mechanical advances and the ensuing specialization of labor.

Within this environment, companies started to engage welfare workers, who were chartered to examine and monitor the quality of life in the workplace and to make improvements wherever needed. These welfare workers delved into alleviating concerns for worker health and sickness, among others. However, some of these welfare activities were considered intrusions and were, in many cases, inappropriate.

Welfare workers were then transformed into personnel officers, who were given the tasks of testing, hiring, training, and adequately compensating employees. This revamped concern for the human being in the workplace, however, was not enough to satisfy the social movement. Employee benefits as a discipline had yet to appear ubiquitously during this period.

Eventually, the government decided to intervene, and so we saw the introduction of massive social legislation. With these laws, alongside growing demands from unions for medical coverage and pension plans, the landscape of employer-employee relations was changed forever. Within the context of these changes, employee benefits, as a structured offering, came into being.

In the human relations era, the field of human resources management became prominent, further evolving management philosophy. Human resources professionals became advocates for both employer and employee interests. The “human side of the enterprise”3 was considered a pivotal factor in a business’s success. These advocates recommended newer, more effective benefit programs for workers. They argued that the introduction of such programs would enhance employee job satisfaction, thus increasing productivity.

3 McGregor, Douglass. The Human Side of the Enterprise. 25th Anniversary Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006,.

Changes in the Legal Environment

One major reason why employee benefits have become such a significant part of the compensation structure is the evolution of the legal environment. Political, social, and economic pressures morphed into legal protection through the passage of many landmark laws that dictated the incidence and the terms and conditions of mandated benefits. Business, labor concerns, and technological innovations all added to the impetus to provide job security and protection.

Between 1900 and 1950, most of the major legally imposed workplace employee benefits were enacted. These major legislative efforts culminated into the Social Security Act of 1935. In the realm of wage and hour laws, both the Walsh-Healy Act of 1936 and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 saw the light of day. By 1950, minimum wage laws had been put in place; further, unemployment and workers’ compensation laws were enacted in most states. Social Security benefits were being paid; private pension plans and insurance coverage were also being demanded in union negotiation.

Under the umbrella of religious and philanthropic interests, certain groups sought to influence employers to elevate workers’ living conditions. There was talk of universal healthcare, disability protection, and old-age benefits. The question arose, however: Who should be responsible for providing this protection, the government (state or federal) or the employers? This debate continues to this day. Consider, for example, all the debate that accompanied the passage of “Obamacare” and still went on after the law was passed.

These discussions and associated demands introduced the concept of an employer’s social responsibility. Businesses, concerned about rising costs and equally declining profits, opposed these impositions. However, politicians—spurred on by the elderly, the disabled, and the unemployed in their constituency—continued to pressure their legislators. Thus, fearing intervention and mandates, employers were forced into providing these adequate benefits to their employees.

Thanks to these initiatives, a legal frame was constructed for employee benefits, which covered the following:

• Workers’ compensation: designed to provide protection in the case of job-related injuries and accidents

• Social Security: old-age protection financed jointly by employers and employees, with the government insuring its continuation

• Unemployment insurance: maintaining the living standards of the unemployed workforce

Note that these legislations were contentious, and they remain so even in the most recent political environments. Public policy debates on these laws remain as loud as they were when they were first discussed and put into practice. This legislative framework is now directly bumping into escalating costs.

Because of the forces previously described, as well as the fact that the U.S. political consensus differed from Europe, workers’ benefits were financed by a number of sources: both the state and federal governments, private employers, and the individual employee, in what is known as the three-legged stool approach. The U.S. government provides Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and unemployment benefits. These first two programs are financed by both the employer and the employee, while private employers provide healthcare, disability, and retirement benefits.

Employers typically finance these programs, or else co-finance them with their employees. Employers also receive tax incentives when certain benefits are offered. Individual employees maintain their own insurance coverage for certain losses, and they pay for these from their own resources.

Tax Legislation

Within a legal context, tax legislation has also played an important role in the increase of employee benefit plans in organizations. This legislation has favored these plans, and has provided some impetus to their development by making the following:

• Company contributions to employee benefit plans deductible

• Contributions made by the employer, on behalf of the employee, nontaxable income for the employee

• Retirement contributions made by the employer, on behalf of the employee, untaxed until the employee receives benefit distributions

These tax-favorable consequences have contributed to the development of employee benefits, inasmuch as the design of these plans attempt to maximize tax advantages.

Recent Changes and Trends

Particular changes in the development of employee benefits have taken place over the past 15 years or so, which have been triggered by the ever-increasing costs of providing said benefits. Along with increasing costs, many additional changes have occurred in the legislative environment in the form of more laws, regulations, accounting rules, and both internal and external control requirements. Furthermore, during this period, Human Resources departments—the ultimate custodians of employee benefit plans—have seen major budget cuts; the theme is “doing more for less.”

Due to these pressures, employers have been required to shift some of their costs to providing competitive benefits to their workers, seeking to make them more informed consumers with regard to these benefits plans. In a sense, this has transferred some of the responsibility of managing benefits to the employees themselves (as discussed later in this chapter).

As such, it can be seen that the administration of employee benefits has grown, and continues to grow, steadily more complex, which has created a growing importance in the need for management focus.

This focus becomes critical when one realizes that effective management of these programs can facilitate cost control and, at the same time, assist with efforts in the areas of improving productivity, the management of risks, and the improvement of employee satisfaction.

Further, this complexity has created the need to bring more skills and talents, from various professional disciplines, to the table, including the following:

• Accountants

• Actuaries

• Attorneys

• Benefits consultants

• Benefits personnel

• Compensation and reward specialists

• Group insurance specialists

• HR specialists

• Insurance agents and regulators

• Investment specialists

• Plan administrators

• Trust officers

The fact that these extremely varied professions bring different perspectives to bear on the subject of employee benefits has led to a need for a common language for communication, analysis, and synthesis. This common language, and thus a common understanding, can be facilitated only through the languages of business: accounting and finance.

Also relevant are recent changes in the operating environment. First, there has been an increase in the incidence of new benefit options. In the past, a typical program would involve medical benefits, group life insurance, accidental death and dismemberment benefits, retirement benefits (either a defined benefit plan or a defined contribution plan), and various time-off benefits.

We will now explore some recent changes in the working environment that currently have had a major impact on the design of employee benefits programs.

The following is a compilation of these newer benefits being offered by various organizations:

• Healthcare benefits

• Health savings accounts

• Healthcare premium flexible spending accounts

• Health-reimbursement arrangements

• Point-of-service (POS) plans

• Acupressure/acupuncture medical coverage

• Experimental/elective drug coverage

• Gender reassignment surgery coverage

More and more, we find that healthcare benefits are being provided to additional classes of employees, such as the following:

• Same-sex domestic partners

• Opposite-sex domestic partners

• Nondependent children

• Foster children

• Dependent grandchildren

Carrying on with our review of the newer forms of employee benefits, we find the following:

• Preventive health and welfare

• Health and lifestyle coaching

• Wellness programs

• 24-hour nurse hotlines

• Smoking cessation programs

• Health fairs

• Fitness center benefits

• On-site fitness centers

• Nutrition counseling

• On-site fitness classes

• On-site medical clinics

• Healthcare premium discounting for annual healthcare risk assessments

• Healthcare premium discounting for avoiding tobacco products

• Rewards or bonuses for completing certain health and wellness programs

This plethora of preventative health and wellness benefits attest to employers taking aggressive, direct, and indirect actions to reverse the tide of escalating costs for providing healthcare benefits. Employers today are searching for more ways to develop and maintain a productive and engaged workforce by providing services that assist their employees in maintaining both their physical and mental health.

Continuing with our review of new benefits, we find the following:

• Paid time-off plans, combining traditional vacation time, sick leave, and personal days into one comprehensive plan

• Paid personal days

• Paid family leave

• Paid time-off for volunteering

• Paid adoption leave

• Unpaid sabbatical programs

• Family friendly benefits

• Adoption assistance

• Dependent care flexible spending accounts

• Childcare referral services

• 529 plans

• Elder care referral services

• Flexible working benefits

• Telecommuting

• Flextime

• Compressed workweek

• Job sharing

• Break arrangements

• Mealtime flex

• Shift flexibility

• Retirement benefits

• Supplemental executive retirement plans

• Cash balance pension plans

• Roth 401(k) plans

• Employee referral bonuses

• Full flexible benefits

• Credit counseling services

• Payroll advances

• Spot bonuses

• Financial advising services

Note that the environment of employee benefits is constantly in flux. Continuing changes in the business environment can affect the design and planning of benefits. An individual company can control some changes, but not all.

Companies facing financial challenges are often forced to cut employee benefits provisions or ask employees to share in more of the costs of providing these benefits. Legal changes can also affect the composition of these plans. Mergers and acquisitions often dictate changes to benefits plans, as well.

Legal changes are often constant. Recent changes have affected qualified versus nonqualified plan definitions. Further, legal changes can affect the tax provisions that affect benefit plans. They also can affect plan language and disclosure requirements. Above all, there is a great deal of uncertainty as to how the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) might affect benefits planning going forward from 2014.

A company’s financial environment also has a major impact on designing employee benefits. If times are favorable, companies might introduce new, attractive features to their benefits program to attract and retain high-caliber employees; however, if times are unfavorable, benefit provisions are often cut, or employees are asked to bear more of the costs.

In a merger and acquisition situation, a line item-by-line item comparison of is made of each of the benefits programs for the companies involved in the transaction. Based on these findings, the new company’s management will adopt the best of both plans’ provisions, or they may decide to come up with new provisions entirely. The key is to decide on provisions that would be welcomed by employees during the often trying times following the merger or the acquisition.

When companies realize that workforce characteristics are undergoing changes due to societal shifts, benefit plan provisions are often changed. The needs of younger employees often differ significantly as compared to the needs of their elders. Lifestyle benefits, in particular, have become a much-discussed topic in recent years.

In addition to monetary compensation and a healthy, positive work environment, employee benefits have become a key component of human capital strategies in most companies. Recent surveys of employee attitudes on a wide range of workplace issues have shown that a significant percentage of employees want better benefits. It is interesting to note that younger employees who are entering, or are already in, the workforce are more focused on this particular issue than their predecessors. Whether this is because fewer companies are offering comprehensive benefits packages or because of higher expectations in the recent generations of employees is unclear; nonetheless, these challenges remain issues of concern for employers going forward.

Employee Benefits under Adverse Economic Conditions

It has been observed that during the recent economic recession, employees valued their benefits more than ever. Behavior shifts and modifies during tough economic times, and as a result, certain decisions are modified. For instance, workers become much more hesitant to leave work for extended periods of time, such as for a vacation or because of illness. If employees do leave, such as for maternity or adoption leave, they will return sooner than expected.

In addition, employees are often more willing to pay more for premiums and accept higher deductibles, in hopes of preserving the most desired of all benefits: medical coverage. It has been found that if this benefit is tinkered with, employee dissatisfaction peaks, to the point where they have gone on record to state that they would seek alternative employment if their medical benefits were curtailed or, worse, eliminated entirely.

Furthermore, in such economic turmoil, employees are more willing to entertain reductions in salary, or even forfeit bonus payments, so as to leave benefits at their current levels. Also, a majority have agreed to forego raises in cash compensation to preserve benefits.

Because of these facts, employers would be wise to keep employee preferences in mind, as well as satisfaction levels, whenever considering any readjustments or, particularly, cuts to their employees’ benefit programs during an economic downturn. Employee opinion surveys have consistently indicated that negative action by management, with regard to these programs, in such a climate will also dictate how those same employees feel about their employers once the company’s economic situation improves.

Strategic Considerations in Designing Employee Benefit Programs

Specialists engaged in developing and administering employee benefit plans face some strategic design questions at the outset:

1. What is the competitive profile for the right functional benefits to be provided?

2. What specific features should be provided within each provided program?

3. Which class of employee should be covered under each program?

4. The how, why, when, and what involved in financing these programs.

5. What are the tax, accounting, recordkeeping, legal, auditing, risk-mitigation, and actuarial considerations of provided programs?

6. How should the plans be administered?

7. How should the plans be communicated?

Each of these questions is critical, and must be addressed. The purpose of this book is to assist with addressing questions 4, 5, and 6. The need for this strategic approach is accentuated for the following reasons:

• Benefits are a major part of an employee’s total compensation package in most organizations; benefits have a distinct advantage in that they can be a tax-effective way of compensating employees.

• Benefits can be a significant cost item for most organizations. In tight economic conditions, it becomes imperative that employee benefit costs are managed and controlled both strategically and effectively.

• Employee benefits are continuously buffeted under changing tax or labor laws, as well as the regulatory climate. Because of this fluidity, it is important to take a strategic, systematic approach to employee benefits planning. A recent example of these phenomena comes to light by uncertainties created by the recently enacted PPACA. This law seems to demand that employers solve societal problems by way of their employee benefit plans.

The Integrated Systems Approach to Employee Benefits Planning

The environment in which employee benefits operate is often erratic. For a number of strategic reasons, it is imperative to use a systematic process when designing, planning, and administrating workers’ benefits. One useful option is known as the integrated system approach, which has been in use for some time now. It is an organized process of classifying employee life events and extrapolating the employee’s needs from that classification. In this system, employees are put into categories of exposure to life event losses and their protection needs.

These needs can be organized into numerous categories, including the following:

• Healthcare (medical, dental, and so on)

• Losses resulting from employees’ (and their dependents’) deaths due to medical issues or from the risk of accidents

• Losses from disabilities, both short and long term

• Financial security needs from retirement

• Capital accumulation needs, both the short and long term

• Economic security needs from unemployment

• Health and financial protection from workplace injuries and accidents

• Long-term medical care, custodial care, and life care needs

• Dependent care assistance needs

• Plans that meet non-discrimination rules

• Needs for educational assistance for employees and their dependents

The objectives of this approach are the structuring of benefits to ensure that employee needs are met while mitigating loss exposures. This assists organizations in managing costs and also assists with employee communication.

It has been shown that this process helps to integrate employee benefits into a total compensation strategy, and from there, the integration of the compensation strategy into human resource (or human capital) plans for the organization at large. When designing a total compensation program, an employer will typically seek to integrate the program’s various elements—base compensation, incentive or variable compensation, and so on—with equity compensation and the various functional employee benefits into a cohesive strategy.

Some employers choose to set their total compensation and benefits levels equal to the competitive market average. Others set them at varying percentiles above said average. Which benchmark is chosen depends on the organization’s general strategy. For example, a company in need of a highly skilled workforce might set its benchmark above average, so as to attract and retain employees with the skills that they require, because they will be taken from a very competitive candidate pool. In contrast, other organizations might choose a position below average for fixed cash compensation and benefit levels, but target incentive compensation payouts above market. This risk-reward strategy would attract an entirely different sort of employee, with differing motivations, compared to the first example. Alternatively, companies may adopt an average or below-average benchmark with the thinking that savings accrued will outweigh the negative results of a higher turnover rates. The type of industry, and the characteristics of the employer, will determine the total compensation structure.

Within a context such as the one outlined here, a large and mature organization may take a more liberal stance on benefit programs and their relatively high fixed costs. However, a growing organization—particularly in the high-tech sector—might focus more on equity compensation and short-term variable pay in order to conserve resources.

Companies that are cyclical in nature may not want to increase their fixed costs with a liberal program, but instead will seek to cut programs and introduce higher levels of cost sharing with their workers. It is a continuous struggle to keep the right balance in allocating resources to meet employee needs on one hand and fiscal realities on the other.

Another approach entirely to benefits planning involves employers’ inclinations to reward longer service, rather than focusing on needs. This seniority-based system recognizes employee loyalty and commitment. Alternately, benefit eligibility may be tied to an employee’s salary or classification level, which results in a hierarchal system. Both of these differ greatly from the needs-based system, which simply recognizes that all employees (and their dependents) have needs that should be addressed; this is used to derive maximum productivity from the entire workforce.

Most organizations use a combination of these systems, called a dual-objective system. For example, healthcare benefits might be dictated by employee needs, while group life insurance and defined pensions are set based on income.

An example of the steps in the design of an integrated system is as follows:

1. Determine job groups to be covered under the plans:

a. Active, full-time employees

b. Dependents of active, full-time employees (Note that the legal requirement now, under the Affordable Care Act, has increased the age level of dependents covered by this category to 26.)

c. Retirees and their dependents

d. Disabled employees and their dependents

e. Employees temporarily out of work due to layoffs, leaves of absence, military duty, labor disputes, and so on

f. Part-time employees, furloughed employees, and so on

2. Analyze the benefits currently in place. Look at the types of benefits, eligibility requirements and conditions, employee contribution requirements, flexibility provisions, and actual participation rates and experiences.

3. Collect data on coverage that is legally required.

4. Collect data on competitive coverage levels on all functional benefits.

5. Develop the gaps and overlapping elements that exist in the current coverage levels in each category.

6. Prepare an optimum benefits profile, taking into consideration the current gaps and employee needs. Also, in this step, it is important to consider the strategic objectives set for the benefits within the context of the total compensation strategy.

7. Calculate the costs of the program using data sources, benefits consultants, benefits brokers, and insurance company representatives.

8. Develop financing strategies—for example, self-insurance or indemnity plans. Also requiring consideration are cost-saving concepts, ideas, and programs.

9. It is also important to consider the plan’s administrative requirements and needs within the context of third-party administrators, administrative services only (ASO) contracts, and the complete outsourcing or the use of internal administrators. A thorough analysis of the feasibility of outsourcing should be considered along with the ensuing cost savings.

10. Develop alternative scenarios for the benefits profile, based on all the data collected in the previous steps. For each, develop relevant cost data. Include cost-savings strategies within each scenario. Consider cost savings and cost containment in each alternative.

11. Present the report to executive management, stating the pros and cons of each chosen alternative. Also present to management the proposed alternative approach and a financing strategy for the recommended alternative.

12. After securing approval from executive management, communicate the plan to employees.

13. Set up open enrollment and implement administrative plans and processes.

14. Set up a closed-loop measurement system with appropriate measurement metrics.

As shown by this example, an integrated systems approach is simply a method of analyzing each component of an employer’s total offering of employee benefits. This system analyzes the programs as a whole, in terms of its ability to meet workers’ needs, while managing associated risks and loss exposures within the organization’s overall goals.

This can prove very useful in overall benefit plan design, in evaluating cost-saving proposals, and in effectively communicating the employer’s program to employees. Thus, the integrated systems approach (essentially a planning approach) fits logically into a total compensation philosophy and avoids reactions to current fads, outside pressures, insurance, and sales pitches.

The Cost Dimension

The costs of providing an appropriate employee benefit program is of paramount concern. Benefit costs are on the rise. In a study conducted in 2012 by the Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM),4 it was stated:

4 Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM). 2012 Employee Benefits: The Employee Benefits Landscape in a Recovering Economy, 2013. The insurance company Colonial Life sponsored the research and publication of this report.

Organizations spent an average of 19% of an employee’s salary on voluntary benefits (such as medical plans, dental plans, prescription coverage, flexible spending accounts, vision plans, survivor benefits), 18% on mandatory benefits (such as unemployment, worker’s compensation, Social Security), and 10% on pay-for-time-not-worked benefits (regular rate of pay for a nonworking period of time, such as vacations, holidays, personal bereavement and sick leave).5

5 Ibid, p. 63.

This makes up a total of 47% of a given employee’s cash compensation. This is a significant number requiring careful analysis, planning, and control (in essence, the functional approach outlined previously). It further requires the necessary accounting and financial analytical skills. All stakeholders, using the language of business, should undertake conversations on this subject.

The SHRM study also stated, “More organizations indicated that the percentage of payroll reflecting the cost of voluntary benefits (20%) and mandatory benefits (15%) had increased.”6 The study further provided evidence that the slow pace of current economic recovery has negatively affected employee benefits planning in their organizations. This makes the case that the main custodians of employee benefit plans—the HR function—must approach this key area of business success with financial and analytical rigor.

6 Ibid, p. 63.

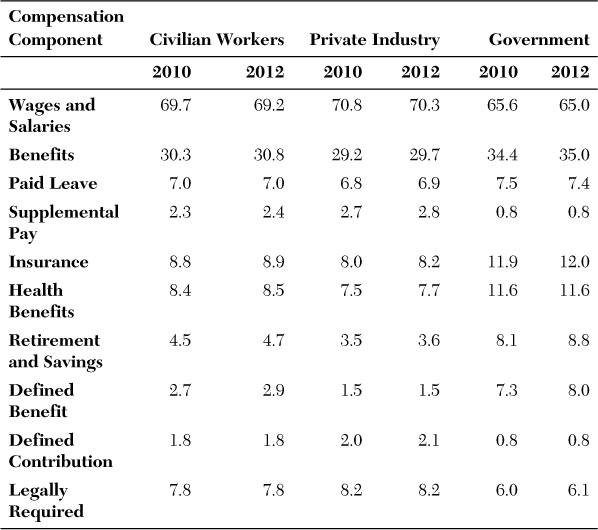

Now, let us look at data from the Bureau of Labor’s statistics shown in Table 1.1.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employer Costs for Employee Compensation–December 2010 and 2012,” p. 3.

Table 1.1 Relative Importance (%) of Employer Costs for Employee Compensation, December 2010 and 2012

This table indicates the following:

• Employee benefit costs average around 30% of total costs. In other words, for every dollar spent compensating workers, 30 cents goes toward benefits. For medium to large companies, the absolute dollar amount can be substantial, requiring all accounting and financial disciplines to be brought to bear in order to manage them.

• Public-sector percentages are higher than those in the private sector. A case can be made that public sector expenses for employee benefits should be brought in line with those in the private.

• Defined contribution plan percentages for the public sector are almost a full percentage point higher than those in the private. As discussed later in this book, defined benefit retirement plans can be quite onerous from a financial perspective. These are commitments of funds (or liabilities) that must be paid out in future time periods. It has been proven difficult to set aside enough funds to pay obligations at future dates.

As you learned in this chapter, it has become imperative that financial and accounting rigor be brought into the management of employee benefit plans. When one adds the complex landscape of corporate scandals, major bankruptcies, and a volatile stock market, all resulting in billions of dollars in retirement plan losses, one can easily recognize that the employee benefits environment is more complex than ever, requiring more diligence in the management of these programs. It has never been more important for in-house benefits professionals and outside counsel, plan fiduciaries, sponsors, administrators, advisors, and insurers to avoid poor or inconsistent drafting, design, implementation, and administration of benefit plans.

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Fringe benefits

• Categorization of employee benefits

• Social Security Act of 1935

• Walsh-Healy Act of 1936

• Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938

• Tax legislation

• Healthcare benefits

• Preventive health and welfare

• Leave benefits

• Flexible working benefits

• Retirement benefits

• Financial benefits

• Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)

• Cost dimension

• Strategic design of employee benefits