12. Human Resource Accounting

Aims and objectives of this chapter

• Define human resource accounting

• Explain the conceptual basis for HR accounting

• Explain the debate with respect to HR accounting

• Describe HR accounting methods

• Review cost-based models

• Discuss the economic value models for HR accounting

• Explain the limitations of each of these models

Thus far in this book we have been discussing human resource (HR) management topics that have accounting and finance implications. The basis of the discussion has been within the structure of current accounting principles and practices as defined by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

The Background

This chapter covers HR accounting, a paradigm-shifting proposition that proposes capitalizing HR expenditures.

Although the previous chapters in this book covered many concepts for the accounting of human resources, the term itself is specifically used by proponents of capitalizing HR expenditures. They use the term human resource accounting to identify this paradigm-shifting concept.

The proposition suggesting the capitalization of HR expenses has been around since the 1960s (although mainly in academic circles). As proposed, HR accounting is a system of identifying, gathering, and reporting of data on the economic investments in human assets. This is an effort to analyze and report on the investments in human resources in a manner that is not a part of the current accounting standards and principles. Human resource accounting (HRA) uses current accounting and finance principles covering the capitalization of expenses and applies those concepts to first quantifying the cost and then valuing the human resources employed.

Fundamentally, the HRA has a two-pronged conceptual basis:

• The quantification of the cost of human resources: Covers all the expenses an organization incurs for acquiring, motivating, retaining, maintaining, developing, and redeploying its HR assets.

• The valuing of human resources: An analysis of the return on investment (ROI) received from HR investments. HRA suggests that the value can be measured by calculating the present value of an employee’s total compensation income earned over the employee’s service period.

As indicated, HR accounting has been around for a while, but mostly relegated to academic dialogue. HRA as a concept was first developed as a research effort at the University of Michigan. Rensis Likert, founder of the University of Michigan Institute of Social Research, along with some colleagues at Michigan (R. Lee Brummet, William C. Pyle, and Eric G. Flamholtz), was responsible for the original work on HRA. The term human resource accounting was first used in a paper in 1968.1 That paper is the earliest study dealing with HR measurements.

This chapter reviews HRA and discusses its efficacy, applicability, and its drawbacks.

The Debate

Some say that current accounting principles as codified in the U.S. GAAP and the IFRS is a legacy of the manufacturing era. Since the early 1970s, the manufacturing era has given way to a service economy. Ever since the advent of the use of technology, automation, robotics, and other process efficiencies, the need for relevant know-how has risen exponentially. Given these structural transformations, it can be said that an organization’s real investments, its assets, and ultimately its value lie in its human resources. However, the accounting profession has not placed human assets in the same place on the balance sheet (or in business valuations) as physical assets.

A manufacturing organization’s core assets are its physical assets: property, plant, and equipment. For service-based and knowledge-based organizations, the core assets are the HR assets. In service and knowledge organizations, human capital is the most important asset employed in extracting value from the organization. This is especially true in purely knowledge-based economics. Imagine Intel, Google, and Facebook without human capital. Without their human talent, those companies would possess minimal value.

Others say that organizational decision makers currently lack complete information on the effectiveness and efficiency of human capital expenditures. But, currently, in financial statements the value of HR assets is not recorded.

The paradigm-shifting concept of HRA is a methodology to bridge this gap. So, HRA is the process for recording, reporting, and analyzing HR expenditures using the language of finance and accounting.

Nevertheless, in the absence of legitimate recognition by the accounting profession for this structural accounting principles shift, HRA will remain the domain for academic discussion and dialogue. Change in this area is slow to come.

HRA proponents suggest that intellectual capital of an organization consists of its human capital and its organizational capital, which is the sum of customer satisfaction, the efficiency of internal processes, and the ability of the organization for continuous learning and development (a learning organization).

Others have postulated that the human capital of an organization can be looked at from a longitudinal point of view—or a human asset life cycle view (see Appendix in Chapter 2, “Business, Financial, and Human Resource Planning”). In this conceptual structure, human assets are acquired, onboarded, motivated and retained, maintained, developed, and redeployed. Thus, human capital assets have a life cycle just like any other physical capital assets.

There is a twofold uniqueness to human capital. Human capital and thus human assets have longer life cycles and most probably appreciate rather than depreciate. Physical assets can only depreciate.

The accounting profession contends that human capital as contained in skills, knowledge, abilities, and competencies of an individual employee is hard to replicate. The accounting profession will argue that the value of one human capital unit (an employee) compared to another is not comparable. One employee’s contribution can be greater than another employee’s contribution. This issue in itself makes it difficult to calculate human asset values accurately. Human capital valuation is therefore hard to quantify. The future benefit to be derived from HR investments is hard to determine. As a result, the accounting profession has avoided including human capital in the financial and accounting records and statements. Under current GAAP principles, all monetary outlays for HR-related costs are considered as period expenses and not as assets.

The problem with this way of thinking is that the more an organization invests (or, based on current accounting thinking, spends), the more an organization’s current net income decreases. The logic here is hard to rationalize. The human resources of an organization (its human capital investments) with their individual and joint effort, skills, experiences, abilities, knowledge, and competencies are solely responsible for creating and adding value to an organization. Yet the current accounting system considers those expenditures as immediate expenditures. This, in turn, reduces the financial value of the organization because current expenditures decrease current income. How can an expense increase and decrease organizational value at the same time?

Furthermore, in analyzing the financial value or viability of an organization, analysts currently use many ratios. But none of these measures consider HR contributions or the human capital value. All of these ratios are based on hard physical capital values only. ROI is also based on investments only in physical capital.

The most glaring outcome of this logical conundrum is found in reduction-in-force decisions (layoffs). When organizations decide to lay off employees, the short-term immediate cost savings is what motivates the decision. The objective of making this decision is primarily to show a short-term increase in profitability. But is this analysis complete? What about the longer-term implications? In the long term, there will be many incremental costs in reacquiring, retraining, and paying pay premiums for replacement hires. One cannot also ignore the negative impact on the remaining employee’s motivation and morale. So, shouldn’t this decision be made with a longer-term perspective?

When investors are considering long-term investments, the data from HRA will provide valuable information about the long-term viability of the enterprise. And shouldn’t we use a capital budgeting approach in making this decision? This chapter’s appendix lays out a model for such an analysis.

HR Accounting Methods

Many computational models have been used for the calculations of the value human resources in an organization. Generally, these models can be grouped into two categories: cost-based models and value-based models. Within each category, you can find various individual models. The following subsections briefly cover each of these models.

The first category of models is cost-based models. Here you can find models that focus on capitalization of historical costs, replacement cost models, and opportunity cost models. The second category of models is value-based models. In this category, you can find the present value of future earnings model (the Lev and Schwartz model), the reward valuation model (the Flamholtz model), and the group-based valuation model.

Cost-Based Models

Acquisition Cost Model

The acquisition cost model was developed starting in 1967, at the University of Michigan, by a research team that included Rensis Likert, R. Lee Brummet, William C. Pyle, and Eric G. Flamholtz. Brummet, Flamholtz, and Pyle published a seminal article in the area of HR measurement in the Accounting Review,2 where they introduced the acquisition cost model. Their research was based on work they had done on employee valuation at the R.G. Barry Corporation of Columbus, Ohio.

The method measures the organization’s investment in employees using the five HR functions:

• Recruiting and acquisition

• Formal training and familiarization

• Informal training, informal familiarization

• Experience

• Development

The model suggested that instead of charging the HR process costs to the income statement they should be capitalized in the balance sheet. Like all other asset accounts, the researchers suggested that HR assets should also be amortized over a determined useful life. It was suggested that the amortization process should also be done over a period of time. The period of time was the difference between the date of hire and the retirement date. It the employee terminates any time during this period, an impairment calculation can be done and an impairment expense taken during the termination year (similar to methods used to account for a physical asset).

For example, suppose that a company had hired an employee at age 35 on January 1, 1991, for an annual salary of $100,000, and the employee left the company after 20 years of service, on December 31, 2010 (normal retirement age is age 60). The company would have amortized $80,000 as of 2010, so the unamortized amount of the annual salary of $20,000 should have been charged to the income in the year 2011.

In essence, the human asset value is amortized annually each year over the expected length of the service of the individual employee, and the unamortized cost is shown as the investment in the human asset on the balance sheet. If the employee leaves the organization (that is, human assets expire) before the expected service life period, the net value of that specific human asset is charged against current revenue as a current expense.

This model has also been referred to as the capitalization of historical costs model. The original classification of the costs by the researchers seemed somewhat esoteric. A better categorization is the sum of all costs related to acquisition (recruitment, selection, and onboarding), total rewards, maintenance (employee benefits and services), training (both in-house and outside) and development, and redeployment.3 These costs taken together would represent the real value of the human resources of an organization.

Another category of costs to consider within the acquisition cost methodology is learning costs. From a managerial accounting point of view, a clear estimation of learning costs is necessary to derive a good prediction of product costs. So, concepts such as the learning factor and experience curves should be brought in to more effectively estimate the true costs of the organization’s learning and development efforts.

The acquisition cost model of HRA is simple and easy to understand and satisfies the basic matching accounting principle for costs and revenues. But, the model has some drawbacks. Historical costs are sunk costs and are irrelevant for decision making. So, the model fails to value human resources accurately from the point of view of using relevant costs. Another conceptual drawback of this model is that because no distinction is made for the differing value of individual human resources (some human resources in an organization are of a higher value than others because of their advanced knowledge, skills, and abilities) and because training costs (specifically) for these employees will be lower (they already possess the much needed knowledge and know-how), they will be given a lower value. Intrinsically, employees with advanced knowledge, skills, and abilities have a higher value for the organization.

Another criticism of this model is that this method measures only the costs to the organization but completely ignores any measure of the value of the employee to the organization.4

Replacement Cost Model

The replacement cost model takes into consideration the costs that would be incurred to replace one individual with another (or one group of employees with another). However, the replacement is based on the exchange of identical knowledge, skills, and abilities (commonly called KSAs). The costs included in replacement costs include the termination costs associated with the terminating employee or the group of employees plus the costs of hiring and training the replacement.

Proponents suggest that the concept of replacement cost has two manifestations: position and personal. So, individual replacement costs cover the costs that have to be incurred to replace an employee by another employee who can provide the same set of services as that of the individual being replaced. Positional replacement costs refer to the cost of replacing the set of services being rendered by an individual occupying a specific position. The positional replacement cost takes into account the position in the organization currently held by the employee. In contrast, personal replacement costs are costs for any specific individual being replaced by another specific employee capable of rendering the specific services. This personal replacement is not connected to any particular position. For practical reasons, this is too fine a distinction and would create data-tracking difficulties.

This is a per-person cost method compared to the average cost method employed by the historical cost method. So in this method, you use the average HR costs for a specific position or employee, which could be held by either one person or a number of employees.

Note here the specific difference between a position and a job. A job entails the roles and responsibilities and the skills required for a specific job. The job can be benchmarked against similar jobs in other organizations. A position includes the cumulative job responsibilities, duties, and tasks entrusted to a specific employee. The individual components that make up the position can be benchmarked. The position provides a more dynamic and flexible framework within which to make salary decisions. For example, clerk is a job, whereas a payroll clerk is a position.

The replacement cost model can also be built around competencies within an organization. Competencies refer to the optimum set of knowledge, skills, and abilities and associated behavioral indicators that are necessary to achieve the company’s strategic and operational business objectives.

The problem with this model is that the determination of the replacement cost of an employee is highly subjective. This is because the collection of the replacement cost data is not a normal part of regular accounting systems or even a part of regular HR information systems. Procedurally, both these systems do not keep track of which terminating employee is being replaced by which new hire. To match replacements, a system can be developed to do the necessary data tracking. For senior management personnel, this replacement tracking will not be very difficult.

Opportunity Cost Model

The opportunity cost model states that the human resource of an organization has to be valued on the basis of the economist’s concept of opportunity cost. This is the value of the benefit foregone by putting it to an alternative use. This is measured by the net cash inflow that is forgone by redirecting a resource from one use to another. So in the HR area, it is the value lost by assigning an employee to one assignment as opposed to another.

The value of an employee is determined by the alternative best use of that employee’s knowledge, skills, and abilities in the organization. The opportunity cost value may be established by competitive bidding within the firm, so that, in effect, managers bid for any scarce employee. This model advocates setting up a market where a competitive bidding arrangement establishes a value for the human resource. Managers bid for a scarce resource and establish a bid price for that resource. The net cash inflow is calculated by the increased profit the hiring entity derives from acquiring that scarce resource. The human asset therefore will have a value only if it is a scarce resource (that is, when its employment in one division denies it to another division).

A selection process is set up to operate this system. A human asset has value only if it is a bid-for scarce resource. The others are not. Only scarce human resources are used in the model. Readily recruited human resources are not scarce and are excluded. Therefore, this approach is concerned with only one section of the human resources in an organization. Of concern are only those internal human assets who have profit-generating special skills. In addition, the special skills can be hired from the external labor market.

Value-Based Models

Present Value of Future Earnings Model

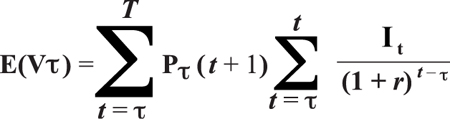

This model of HRA was developed by Lev and Schwartz in 1971 and involves determining the value of human resources by calculating the present value of estimated future earnings discounted by the firm’s cost of capital.5 Exhibit 12-1 shows the expression used to calculate the expected value of a person’s human capital.

Exhibit 12-1. Calculating Human Capital

Where E(Vτ) is the expected value of a person’s human capital and P(t) is the probability of a person dying at age t. Vτ is the human capital value of a person τ years old. I(t) is the person’s annual earnings up to retirement, r is a discount rate specific to the person, and T is the retirement age.

Lev and Schwartz used employee compensation as a proxy for the HR value. Estimated future earnings of an employee were used as a substitute for economic value. According to the authors, “the value of human capital embodied in a person of age r is the present value of his remaining future earnings from employment.”6

The present value model ignores the probability that an individual may leave an organization for reasons other than death or retirement. It also ignores the probability that people may make job or position changes during their careers. Service life is overstated, which results in inflating the value of human capital. It is important to calculate a person’s expected realizable value and not just the conditional value (the value based on the person’s current employment condition).

Reward Valuation Model

The reward valuation model is also known as the stochastic rewards valuation model or the Flamholtz model.

Flamholtz advocated that an employee’s value to an organization is determined by the services the employee delivers to the organization. This takes into account the probability that an individual is expected to transit through a set of mutually exclusive organizational roles or employment states during a given time interval. The assumption here is that an employee provides value to the organization as the employee holds various jobs and positions as he or she moves along a career progression. The realizable value and the conditional value can be calculated as follows:7

1. Define the mutually exclusive transition states or service states.

2. Determine the value of each state to the organization.

3. Estimate a person’s expected tenure in an organization.

4. Find the probability that a person will occupy each possible state at specified future time periods.

5. Discount the expected future cash flows to determine their present value.

The first step identifies time periods or stages when an employee can generate an employment service value to the organization. The second step calculates the value the organization derives by the employee occupying each specific service state. These are service state values. The third step estimates the employee’s total tenure within the organization. In the fourth step, a probability determination is made that a specific employee will remain in that service state at specific future times.

What is the probability that an employee holding a marketing manager position now will remain in that marketing manager position at the end of a specific time period? What is the probability that an individual will leave the organization? These are example of some analytical questions that are posed. Finally, the expected future values are discounted to derive the present value of future benefits.

In this model, the value of each service state is an implied value of what a person in that service state will do during a specific period. The four possible value states are

• Remain in the present position

• Be promoted

• Be transferred

• Leave the organization

These state values form the basis of the valuation in this model.

The major drawback to this model is the difficulty of calculating any realistic probabilities for each likely service state. The methodology for the determination of a monetary value equivalent of each service state is not clearly provided in this model. Also, because this model has an individual employee orientation, it ignores team effort and activities.

Valuation on a Group Basis

Proper valuation of human resources is not possible unless the contributions of individuals as a group are taken into consideration. An individual’s expected service tenure in the organization is difficult to predict, but on a group basis it is easier to estimate the percentage of people in that group who are likely to leave the organization at any specific time. Group valuation of HRA attempts to calculate the present value of the entire group in a service state. You can calculate the group-based present value as follows:

1. Ascertain the number of employees in each group.

2. Estimate the impact of the group using a probability estimate of the termination of an individual group member.

3. Estimate an economic value of each member in the service state.

4. Estimate the value of the entire service state by multiplying the result of the first three steps.

Although the group method simplifies the valuation process in HRA, it ignores the exceptional qualities of specific skilled employees. The performance of a group may be seriously negatively affected if a skilled member leaves (thus reducing the value of the entire group).

Comments on HRA

The theoretical discussion on HRA has value. Why the accounting profession has been slow to embrace these concepts remains a big question. The theoretical constructs of HRA have yet to meet the requirements of current accounting measurement standards. Specifically, the current standards emphasize that accounting principles need to meet the following principles:

• Relevancy for organizational decision making

• Verifiable by independent sources

• Quantifiable in meaningful accounting terms

Recently, there has been a movement toward adoption of more complex measurements compared to the historical costing methods. Time value of money and present value calculations have come into more use by the accounting profession. There has also been a lot of consideration given to the use of fair value measurements. This trend has been accentuated by the convergence efforts between GAAP and IFRS. The fair value measurements are made at each balance sheet date. Many items on the balance sheet that are now noncurrent are being measured at the present value of future cash flows. We have talked about these initiatives in various sections of this book.

So, as the accounting profession diversifies their thinking and becomes accustomed with different and even complex measurement systems, a possibility exists that they will embrace similar approaches taken to measure HR asset values.

Also in current accounting practice it is fairly routine to determine values of intangible assets using accepted accounting measurement techniques. These approaches are even sanctioned by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). It can be argued that the human capital asset is the most important intangible asset in any organization. Given these arguments, it is hard to see why any accountant would consider HRA an unrealistic concept.

Key Concepts in This Chapter

• Human resource accounting

• Capitalization of HR expenses

• Why the accounting profession is yet to buy in to HRA

• HRA methods

• Acquisition cost model

• Replacement cost model

• Opportunity cost model

• Present value of future earnings model

• Valuation on a group basis

• Limitation of HRA

• Valuation of HR assets

Appendix: No Long-Term Savings from Workforce Reductions

Nowadays, more than ever, we see a widespread use of a very short-term business practice: workforce reductions. It seems this practice is quite popular. Business pundits have even coined extraordinary words to describe the practice. Words such as rightsizing, restructuring, downsizing, and delayering are now commonly used to describe workforce reductions. The words being used have legitimized a practice that in reality is just short-term cost reduction. The widespread global use of these practices has climbed steadily over the past two decades. This has resulted in an acceptance of these actions as a common management practice. But when is common practice common sense?

The argument here is that such a practice is ineffective from the human side of the enterprise. The widespread use of reductions in force has emotional, psychological, economic, and social consequences that are far reaching. Use of this management practice destroys people and communities.

In addition to the devastating human consequences, a case can be made that this practice does not fulfill its intended purpose (saving money). Sure, it saves expenses in the short term. It makes income statements look good immediately. However, you cannot be sure about the impact of this short-term cost reduction on the balance sheet. And as discussed previously, accountants are yet to look at human capital investments as assets.

The use of this practice can make business leaders look competent in the eyes of shareholders in the short run. However, long-term investors might recognize that this practice does not really save money. Another key question is how this action affects the intrinsic value of a company over the long term. It can be argued that it ends up increasing long-term costs. Yet, this practice has become a reality in business decision making, especially in bigger organizations.

Workforce reductions result in direct long-term consequences and costs. Very few organizations creatively explore alternatives to saving on expenses before executing the workforce-reduction cost-saving program.

The workforce-reduction decision has resulted in business leaders weakening their organizations through repeated downsizing exercises. In the process, these executives have earned enormous compensation and also fame and glory for “turning the company around.” When HP brought in a new CEO in the late 1900s, the company underwent major reorganization, which involved massive layoffs and off-shoring of the jobs of long-tenured HP employees. These efforts were fruitless because of many other ineffective management decisions. The legendary high-technology company lost 50% of its stock value, resulting in a high-profile CEO termination.

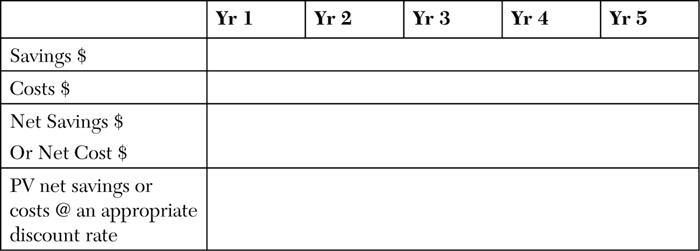

From an analytical point of view, long-term cost savings accruing from massive layoffs is not a reality. Using the concepts of HRA, a financial model can be developed that can prove that over an extended period of time, reduction in force actions do not save money. In fact, they cost more in the long run. The present value concept has been used to develop the following model shown in Exhibit 12-2.

Savings from layoffs (immediate short-term impact):

> Direct labor expenses (–)

> Associated benefits costs (–)

Short-term and long-term costs incurred as a result of layoffs:

> Separation payments (+)

> Replacement hiring costs (+)

> In/out additional compensation costs (+)

> Replacement hires training costs (+)

> Replacement productivity ramp-up costs (+)

> Loss from unused office and other facilities (+)

> Key employee additional retention costs (+)

> Remaining employee demoralization cost (+)

Now do a present value analysis, as shown in Exhibit 12-3.

Exhibit 12-3. PV Calculations of Savings and Costs

So, if you calculate the impact of workforce-reduction policies using this model, you might see a different reality.

After all, the fundamental value measure of a company is its intrinsic value. Intrinsic value enhancement is mainly a result of increasing free cash flows. So, managers can enhance company value by focusing on increasing the size of expected cash flows. Also, the true value of a company is based on future cash flows and not just cash flows in the immediate, short-term time period.