Chapter 6. Scenes I Can Cut!

The first film dailies of Cold Mountain were screened on July 17, third day of principal photography.

A motion picture in the making is often more mysterious and complex than any one person can fathom, be it writer, producer, director, or editor. Luckily, movie directors who work with Walter Murch get an editor who wears more than one hat. Murch is a film editor and sound mixer, but he has also worked as a sound editor and designer, screenwriter, and director, so he can see a motion picture from many sides. His own varied interests—music, physics, translating Italian literature, history, astronomy, and beyond—likewise give Murch numerous entryways for discovering the secrets of a film. The material can tell filmmakers what to do, just as novelists say their characters often guide the plot, but you must know how to hear. Murch watches, listens, and contemplates, using a set of dependable tools he has acquired over 30 years.

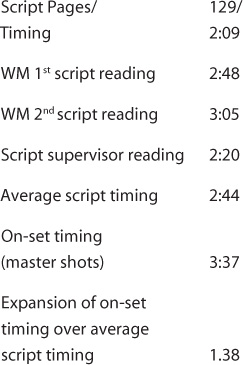

For everyone involved in shooting the film, the screenplay is the front door, the portal to the story’s interior. But for the editor, once closeted with actual footage, the written document doesn’t remain useful for very long. It guides the editor’s first assembly—all the scenes, as shot, put together in order, as written, but films are rarely released exactly as written. For one thing, most of them would be too long for audiences to tolerate. The rule of thumb is that one page of script equals one minute of screen time. But with certain directors, Anthony Minghella included, that formula isn’t too reliable. The shooting script for The English Patient, for example, was 121 pages. Applying the one-page/one-minute equation, the first assembly should have been 2:01 hours. In fact, it was 4:20, more than twice as long. The final released version was 2:42.

Once a scene starts getting transformed from words on a page to film on the screen, all bets are off. Some directors, like Hitchcock and Spielberg, shoot exactly what’s in the script as written; it’s a way of working that suits their personalities. But they are the exceptions. Most directors find their conception for a particular scene changes once they’re on the set. The tempo of actors’ dialogue and the blocking of their movements, the vagaries of light and costume, can change the way a scene gets executed. New material might be added; planned shots may be jettisoned due to weather, schedule, or actors being unavailable; “coverage”—having multiple camera angles on the same action for the editor to choose from—might be compromised, causing a scene to be drastically re-imagined. The editor necessarily works with the material provided, rather than what was imagined but never shot.

An Editor’s Tools

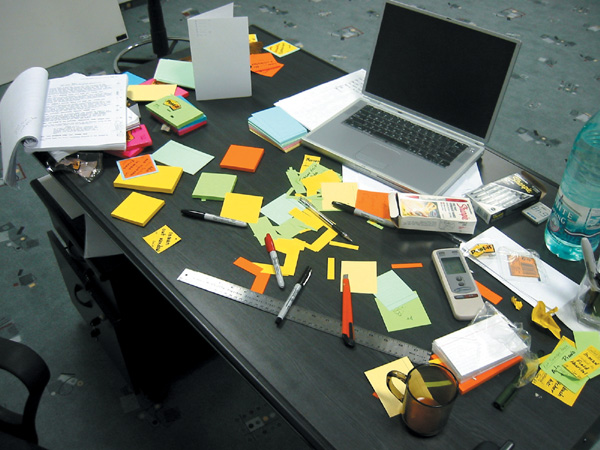

What does an editor use to think about the film? Every editor has his or her own methodology. For Murch, it’s as if he builds himself a personal radio to tune in to the film using several different frequencies: picture boards with up to seven key images from each setup captured and mounted on black foamcore; two sets of script notes—one written on viewing dailies, a second on re-screening footage before editing a scene—which are embedded in his FileMaker log book; and handmade scene cards, coded by color and shape to delineate plot trajectory and the flow of characters.

So now, on the third day of filming in Romania, with Sean Cullen getting the Final Cut Pro systems plugged in and working upstairs at Kodak Cinelabs, Murch begins preparing his scene cards.

July 17, 2002, Murch’s Journal

About 1/4 way through scene cards. I am doing them by hand this time, easier to look at. What color should Inman’s trek be?

On his last few films Murch prepared the scene cards using FileMaker on the Macintosh. For Cold Mountain he goes back to making them by hand. “There is something appealing about the visual handcraftedness,” Murch says later. “The personality of the handwriting is more engaging to the eye, especially if I’m going to stare at them for a year and a half.”

July 18, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Working still on scene cards. Amazing how long it takes always. But good I am doing them by hand this time, not computerized printing.

The scene cards, picture boards, and script notes are simple and uncomplicated tools. But they aren’t just different methods of cataloging. Like composer and printmaker John Cage’s throwing the I Ching to determine creative choices, these tools allow Murch to incorporate randomness into the edit process. If a scene isn’t working for some reason that isn’t readily apparent, a sideways glance at the picture boards might reveal a hiccup in the pattern of images that wasn’t obvious before. Let’s reshuffle the scene cards and see what color pattern emerges. Or, a simple script note (“alt line reading”) made in dailies may turn out to unlock a solution—as the alternate line reading, “He’d kill us if he had the chance,” did for The Conversation. But it requires forethought and effort to plan for the unplanned, to invite the unexpected, and to prepare these alternate tools for working on a film. Taking two days to prepare handmade scene cards at the start of production may seem extravagant. But film directors who embrace Murch’s style know that if they find him in his editing room cutting card stock into odd little shapes, what looks like child’s play is really serving the best interests of their film.

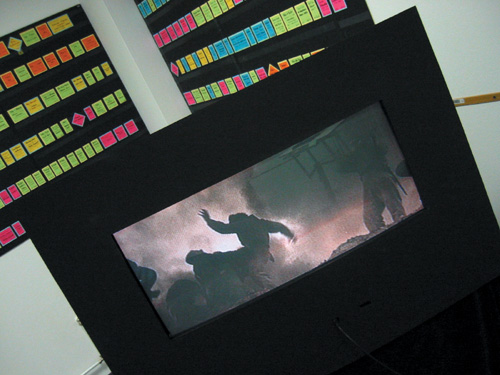

Murch’s scene cards in progress for Cold Mountain.

“Blue with a yellow background means Inman is in a scene; plain blue means Inman is not in that scene. A lot of blue cards in a row means not much Inman—which makes me wonder ‘is that a good idea?’ A triangle indicates I feel it is a pivot scene. The size of card equals the approximate length of a scene.”

Ironically, the more techno-centric film editing gets, the more powerful Murch’s custom-made innovations become. The organic qualities of the scene cards and photo boards compensate for perspectives that are hidden in the digital world. The efficiency, speed, and increased choices of non-linear editing all have their benefits. But systems like Avid or Final Cut Pro obliterate some film editing tasks that contribute to the editor’s creative process. As Murch often points out, the simple act of having to rewind film on a flatbed editing machine gave him the chance to see footage in another context (high-speed, reverse) that could reveal a look, a gesture, or a completely forgotten shot. Likewise, the few moments he had to spend waiting for a reel to rewind injected a blank space into the process during which he could simply let his mind wander into subconscious areas. With random-access, computer-based editing, a mouse click instantly takes the editor right to a desired frame; there is no waiting, no downtime—and fewer happy accidents. The photo boards are one way to compensate for this.

Murch assembles his picture boards as film dailies become available. These postcards from the film provide him another tool to see the movie.

“With computer-based editing, there is no downtime—and fewer happy accidents.”

Film-based editing is now referred to as “destructive editing” in contrast to the “non-destructive editing” of computers, also known as non-linear editing. When a scene is edited the old way—on film with taped splices—the only way to see if it might work better with, say, a different order of shots (the wide shot at the end of the scene instead of the beginning, for example) is to pull the scene apart at the splices and rejoin it in a different order. Not only does this take time to execute physically, the first version now no longer exists (unless a videotape copy was made along the way). In digital editing, the scene can be re-cut over and over again, and all the versions are preserved for later consideration. The computer program plays the footage by sending a request to the hard drives where the original media is stored: “play setup 293-take 4, from frame a to frame b.” With a couple of keystrokes that command can be changed to: “play take 293-take 5, from frame c to frame d.” Both versions still “exist” since no media has actually been touched (destroyed).

Digital editing, being so versatile and fast, provides film directors with many more choices than they have in film-based editing. When a director comes to the digital editing room to look at a newly re-cut scene, he or she can see the new version, the old version and—after a few clicks, have the editor play a third, recombined version of the other two.

Much of an editor’s energy, and most of the assistant editor’s, is spent organizing, logging, tracking, storing, and—like the sorcerer’s apprentice—trying to stay in control of a huge volume of material. To get an idea of how much raw film footage is at the editor’s disposal, recall the shooting ratio—the amount of film shot, compared to the amount of film used in the final theatrical release. It can range from 10:1 in low-budget independent films to 100:1 and more, depending on the style of the director. Stanley Kubrick, for example, was notorious for doing a hundred or more takes of the same shot. At the other extreme, Clint Eastwood is often satisfied after one or two takes. If a shooting ratio is 50:1, and the running time of the finished film is two hours, that means there will be 100 hours of raw footage, or 540,000 feet of film (16 frames of film equals one foot, or .66 seconds). That’s just over 100 miles of film!

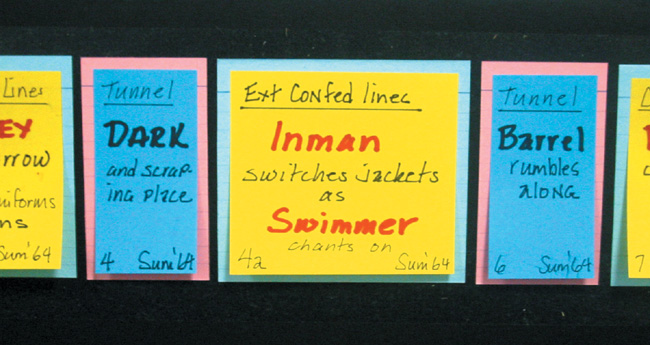

With so much footage to organize, it’s no wonder that in film-based editing chunks of footage often get lost. The missing pieces are usually “trims,” or snippets of film only a few frames in length. These little bits multiply as a film is winnowed down to its essential self, shedding microseconds here and there as the editor finds the truest 1/24 of a second for a shot to begin or end on. The black hole that swallows film is called the trim bin, a square metal container the size of a shopping cart, lined with muslin to minimize film scratches, where the trims are hung on hooks.

A standard film trim bin.

But trims fall off their hooks in the commotion of editing and disappear into the hamper like socks in the laundry. Having to search around the bottom of the bins for a missing trim was an assistant’s tortuous, painstaking job. One of Walter Murch’s contributions to the film editor’s tool kit, the Murch Bin, helps minimize this problem of footage vanishing from sight.

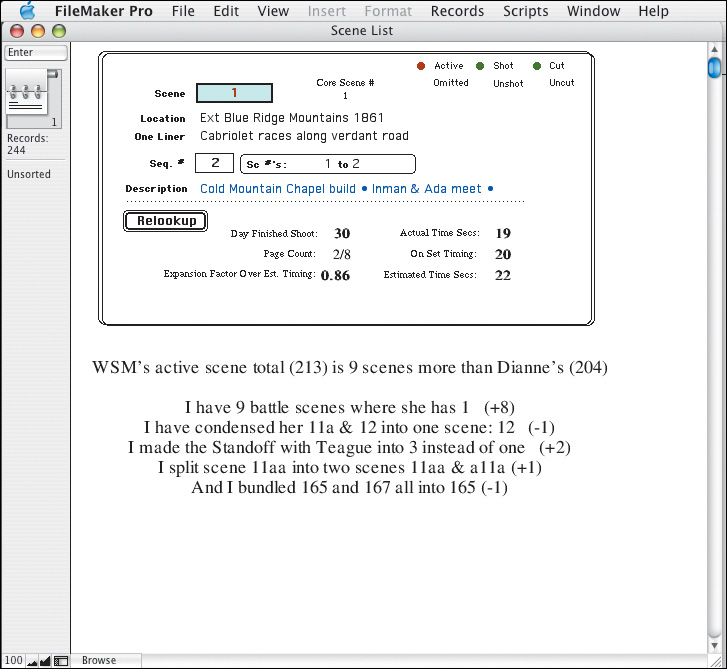

All editors use an accounting method to keep track of film footage. There is no one, industry-standard way to do it; each editor devises a system that suits his or her needs. Murch put his logbook together in FileMaker Pro, a database program that can search, find, calculate, and view by using multiple fields of information, customized to his preference. Each record represents one continuous camera take.

The “Murch bin” uses the ends of crochet hooks instead of straight metal pins. Rubber bands make trims even more secure. Bicycle wheel clamps allow an editor to raise or lower the cross-beam to suit her needs.

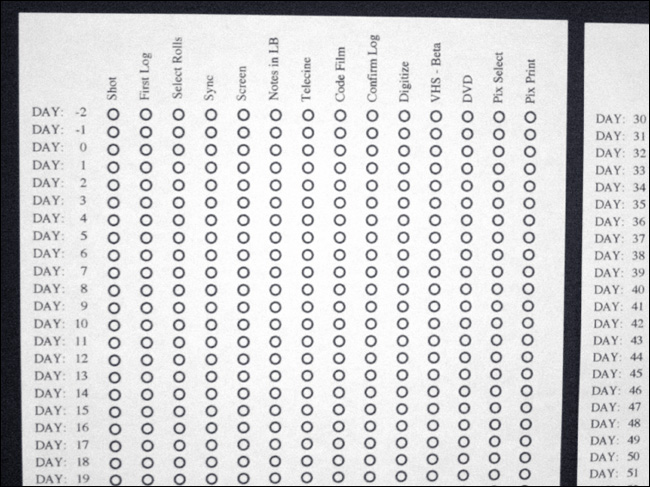

A page from Murch’s Cold Mountain scene list kept in a FileMaker Pro database.

JULY 23, 2002, BUCHAREST, ROMANIA

It is a week after principal photography began, and as film footage flies into the second floor at Kodak Bucharest, record keeping begins in earnest. Now that he has eight days’ worth of material, Walter makes his first estimation about how much film volume he can expect, based on a shooting schedule of 110 total days.

July 23, 2002. Murch’s Journal

354 Records as of today which represents 8 days of shooting. So 45 records per day x 110 days = 4955 or almost 5000 records at the present rate, first and second unit both using multiple cameras ¶ Tuesday, September 3, 2002 that rate is still holding: 45 a day, at 103 feet per take, so average 5000 feet of dailies a day. Grr. That would be 550,000 feet at the end of it all... ¶ 11/23/02 it’s going to be close to that: around 520,000 feet ¶ 01/23/03 It was 4900 records and 597,000 feet!

Recalculations over the course of production, as indicated by the different dates in this journal entry, show that Murch’s initial estimate for the total number of records is essentially correct. But the amount of footage—nearly 600,000 feet—turns out to be even higher than he projected. “This was the most amount of film for me to handle as an editor on my own, ever.” There was twice as much footage on Apocalypse Now—1,250,000 feet, or just over 230 hours—but on that film Murch was one of three film editors working simultaneously. And post production lasted over two years.

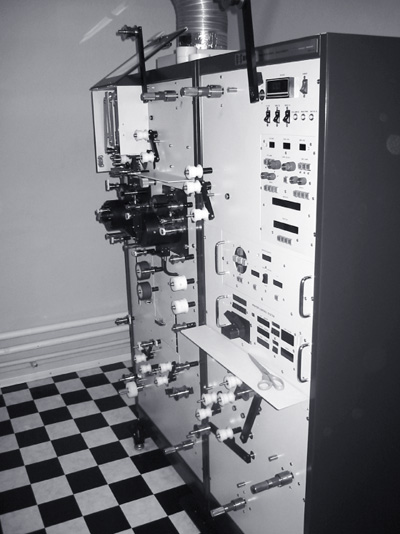

Technicians at Kodak Bucharest assemble processed negative film before it is transferred to video-tape on a telecine machine.

The telecine machine at the Kodak lab for transferring film to videotape.

Why does the quantity matter so much? Is it simply a fact to be marveled at, a statistic to obsess about? Not at all. As Murch later explains, “It’s in my job description. I should be able to tell a director—Anthony in this case—that at this pace of shooting the assembly will be over five hours long.” The length of the assembly matters because it may determine whether the director, who is responsible for delivering a film on time and on budget, fulfills his or her contractual obligations. Other crew members and production executives keep track of production costs and scheduling issues; but only the editor can predict with any certainty if the schedule for editing is accurate, given the amount of work and footage to come. Moreover, the time it takes to edit a motion picture relates, in large part, to the length of the first assembly. The more footage an editor and his or her crew have to begin with, the longer it will take them to assemble it all, and then the longer it will take to pare it all back down to a releasable length. Cold Mountain was originally scheduled for 26 weeks of post production in London. While still in Romania, the producers adjusted this timetable upward; in the end, post production wound up lasting 46 weeks.

At this early stage, Murch also has his eye on what he calls the “30 percent factor”—a rule of thumb he developed that deals with the relationship between the length of a film and the “core content” of the story. In general, 30 percent of a first assembly can be trimmed away without affecting the essential features of the script: all characters, action, story beats will be preserved and probably, like a good stew, enhanced by the reduction in bulk. But passing beyond the 30 percent barrier can usually be accomplished only by major structural alterations: the reduction or elimination of a character, or whole sequences—removing vital organs rather than trimming fat. “It can be done,” says Murch, “and I have done it on a number of films that turned out well in the end. But it is tricky, and the outcome is not guaranteed—like open-heart surgery. The patient is put at risk, and the further beyond 30 percent you go, the greater the risk.”

In the case of Cold Mountain, a first assembly of five hours would mean that the 30 percent barrier would be encountered when the running time had been trimmed to three and a half hours: still too long, most likely, for theatrical release. To get below that length, the prognosis is for drastic surgery—unless some solution can be found now, during production, to cut the script or change the pace of shooting—very serious considerations.

But for now it’s landmark day. The workflows, patches, plug-ins, and workarounds that Sean Cullen and DigitalFilm Tree put together finally pay off: The first Cold Mountain footage pops out at the end of the pipeline, digitized, on Walter’s Final Cut Pro desktop.

July 24, 2002, Murch’s Journal

First Digitize!! And we set the rate at two megabytes per second. Looking at a CU of Swimmer. It looks very good. Congratulations, we are beginning to be sort of up and running.

Once again, there isn’t much time to celebrate. A movie is all about story, and the demands of story soon assume center stage. One of the Miramax executives, Bob Osher, visits the set and sits in on dailies screening. He takes note of the same troubling issue that Murch and the director of photography, John Seale, discussed earlier: will an audience understand how the Union army gets stuck in a pit they themselves created when they set off the massive explosion beneath the Confederates?

The opening shots of Cold Mountain show Union soldiers laying explosives under the Confederate fortifications. The huge explosion beneath the Confederate army’s entrenchment momentarily buries Inman, the protagonist. The Union army’s next move—a ferocious charge at the disrupted Confederate lines—occurs while a mushroom cloud rains dirt and mud down on all the fighters. It isn’t easy to tell one side from the other, nor is it entirely clear that the Union’s charge into the crater wasn’t deliberate. How will the film be able to show events clearly enough for the audience to understand what is happening, yet not so clearly that the Union soldiers look foolish for trapping themselves? It’s a proper question for Murch to have on his radar, but it won’t truly be addressed until he begins cutting the scene.

Meanwhile, Murch’s request to bring on a third film assistant has been approved. Final Cut provides digital film sound that can easily be played back from a portable Akai digital dubber, so location dailies will be screened using a portable Arriflex Loc-Pro projector linked to the Akai—a system that any production assistant can operate. Consequently, the money budgeted to hire a projectionist is freed up to bring Dei Reynolds to Bucharest from London. But Reynolds hasn’t yet arrived and pressure mounts. Being shorthanded and under the gun, Walter works with his son and with Sean Cullen to prep film dailies. The job of ushering film through the lab, rearranging the footage in the order Anthony wants to see it, and getting it synched up with sound on the ProTools system—all in a morning—is usually handled solely by assistants. But as the footage piles up Murch must step in to help. In his journal he simply writes, “Too frantic dailies prep.”

During the battle scenes, the first and second camera units are both shooting at the same time, each with up to four cameras. Plus there are five Eyemo cameras, 60-year-old refurbished hand-held movie cameras originally used during World War II. The amount of film being processed every day averages 5,000 feet, or almost one hour, though on certain days that balloons to two hours or more.

Minghella requested that the dailies be broken down into “selects” and “non-selects”—select rolls being made up of just one good take from each camera setup, in shooting order. This gives him the flexibility (after a long day’s shooting) to see a short but essentially complete selection of dailies—20 minutes of film on an average day. But the non-selects (the other forty minutes of dailies) have to be available, just in case. A camera setup is literally that. If the camera is moved—or even a lens changed—for the purpose of getting a closeup angle of what was just shot from a medium angle, for example, that is considered a different setup, and given a new identifying number. The actor’s dialogue and movements may be exactly the same, but the shot is regarded as distinct.

Preparing a “selects roll” that samples each setup adds an extra side-step to the preparation of dailies. The lab processes and prints in “camera rolls,” in the order footage actually goes through the camera. So the assistants must break down the film print from each camera roll into individual shots, pull out the proper ones, splice these together for projecting dailies, and then find the sound to go with them.

The day after Murch’s Final Cut Pro system finally receives its first digitized material, ready to cut, just when the road ahead seems clear, the external world intrudes with some disheartening news. Walter unexpectedly receives a long letter from Will Stein, the senior executive at Apple managing the Professional Applications Development group (“Pro Apps”), which includes Final Cut Pro.

Stein first acknowledges the July 7 email message Murch sent to Steve Jobs updating him about how well everything seemed to be going on Cold Mountain. Stein writes that editing Cold Mountain on FCP, “has a lot of visibility inside Apple, and we are very excited to see Final Cut Pro proposed for such a significant production.” Stein looks forward to Murch’s “feedback” about working with FCP.

Stein also responds to Murch’s earlier communication with Brian Meaney about director Minghella being “a little surprised” at Apple’s “lack of enthusiasm in the Cold Mountain project.” Stein writes that Apple’s Final Cut Pro team has “a long-term strategy to push into the high-end film market only when our product and support team are ready to provide a great experience to the feature film production community. What may appear to be a lack of enthusiasm,” he writes, “is actually concern over the quality of experience” given FCP’s missing change list feature, possible rough edges in trim mode, and the issue of OS X not supporting SAN (shared area network) storage—linking editing stations to a central hard drive array through a fiber connection. “Speaking for the team,” he writes, “we would rather encourage you to be a happy partner later than a less-than-happy partner now,” a turn of phrase that had a somewhat ominous ring, given that production was already underway.

Stein goes on to write that advances and improvements to FCP are still in progress. “Based on our project plans,” he continues, “and what I understand to be your production schedule, there is **almost no chance** [Stein’s emphasis] that any of these changes will make it into a stable and shipping version of Final Cut Pro or Cinema Tools in time to be used on Cold Mountain.”

Then Stein says that if Murch is “reasonably confident that our applications (and third-party tools), as they are shipping now, will be sufficient for your needs (and you are looking for that ‘early adopter’ type of experience)—I will be very happy to work with you to extend our support of your project. The types of collaborative efforts you outlined in your message to Steve are exactly the type of thing we look for to help drive Final Cut Pro to the next level in the Hollywood community. I hope all is going well at the shoot, and look forward to hearing from you. Best regards, Will Stein.”

Murch genuinely believed that once he was “in country” and actually using Final Cut, Apple would come through and work directly with him on Cold Mountain. With this letter Murch knows that door is now closed. Later he describes feeling like a trapeze artist caught off-guard when the master of ceremonies announces, with no warning, that tonight’s performance will be done without a net. There’s nothing else to do but swallow hard, trust one’s instincts, and not look down. The show must go on!

Instead of agreeing they’ve reached the end of the road, Murch writes back to Will Stein reiterating their common interests, while also acknowledging the current incomplete state of Final Cut’s version 3.

Cold Mountain • Kodak • Bucharest

TO: Will Stein

FROM: Walter Murch

DATE: July 26, 2002

RE: Apple Cold Mountain

--------------------------------------------------------

Dear Will Stein:

Good hearing from you, and I’m sorry we couldn’t have linked up back in June.

Thank you for your encouragement and your words of caution. We are fully aware that there will be no shippable fixes for FCP by early next year, and we have – or will have by the time we need them – our own solutions for the outstanding concerns, such as Change Lists and OMF export. The smaller issues – such as 4 hour project length, asymmetric trim, ink & key number fields, etc. – I would categorize as desirable but non-essential.

We actually welcome the current state of FCP, in a way, because we hope that some of what we learn on this film can perhaps be integrated into later versions of the software. In fact, other than the excellence of FCP, one of the central reasons for embarking down this road, as I hoped I indicated in my letters to Brian and Steve, is to promote a creative exchange between you at Apple/FCP and us on Cold Mountain.

I am intensely interested in furthering the evolution of cinema post-production, and I see it taking the FCP path. I am, and have always been, in my thirty-seven years of working in film, an “early adopter” personality (to use your words) and fully prepared for the smooth as well as the sometimes rough patches that are part of the territory.

At any rate, we are “in country” in Romania with four FCP stations, happily digitizing and working away – Cold Mountain started shooting two weeks ago – and I would like to reiterate my belief that we both have things to offer each other, and hope that this project can be the field on which the exchange takes place.

Best wishes from sunny/rainy Bucharest,

Walter Murch

The same day Murch writes his response to Stein, he finally gets underway editing Cold Mountain using Final Cut Pro.

July 26, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Response to Will Stein.

First really prowling around on FPC and although slightly awkward, there are some good things. I am keeping lists of things to improve.

Feeling weird—just overwhelmed by things in general—that slightly levitated feel I remember from the first day shooting on OZ after I was brought back on again, in the tower room.

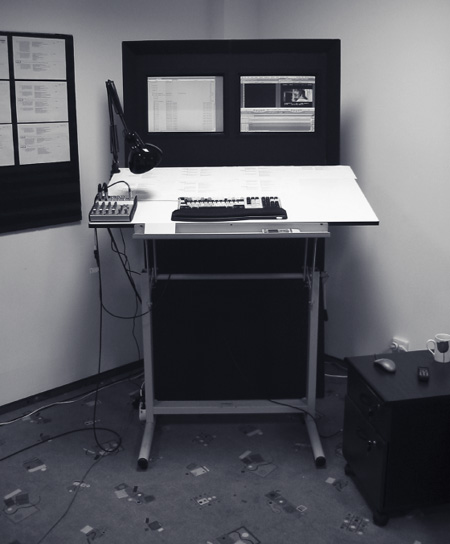

Murch’s Final Cut Pro workstation in Bucharest.

On July 27 Stein writes back with a follow-up: “All required cautions now out of the way, I can reiterate that we are very excited by the project, and will try to be actively involved in smoothing the way for you where possible... Brian [Meaney] and Bill Hudson will also be the leads in terms of organizing technical support where required during your production.”

This dance between Murch and Apple will continue until Cold Mountain is finished.

In Murch’s view, Stein’s initial July 26 letter was the fallback position. Murch reflects a year later: “If, say, two months down the road, everything blew up and we were running around with our hair on fire in Romania, Apple would be able to pull this letter out and say, ‘Listen, we told them this was our position, and they went ahead anyway.’ It was written as a documented record in case there were troubles down the road. Full Frontal, which was also edited in Final Cut Pro, was a qualified experience on both sides; neither party enjoyed it the way they had hoped, and yet that was a low-profile, low-budget film with a very quick turnaround—two weeks of shooting and only a few weeks of post production. Cold Mountain is a different animal and much more visible, so if there was a calamity of some kind, Final Cut’s reputation would be damaged. It would not be their fault but nonetheless they’d be damaged. So it made a lot of people at Apple nervous.”

The Stein letter means the company isn’t going to partner with Murch in any official capacity. Murch had been hoping Apple would be a companion to climb Cold Mountain—together they might take Final Cut Pro to a higher level, working in a mutually supportive way. Murch offered Apple an applied laboratory, so to speak, for testing and improving more advanced uses of its application, and at the end of the process, a high-visibility film Apple could point to as a success. He assumed Apple would openly embrace the chance to put the application to task, with the company stepping in to provide needed solutions and improvements as they arose. He imagined a give-and-take, we’re-in-this-together spirit that defined Murch’s association with Ramy Katrib and DigitalFilm Tree. Instead, Murch will go up the mountain with his own team: Sean, the assistants, DigitalFilm Tree, and Aurora. Apple will stay at base camp, wish them well, and occasionally send up a few supplies and fervent prayers.

Still, Murch doesn’t give up on Apple. Even if FCP is not yet fully developed to accommodate the needs of a major feature film and doesn’t have all the functions he’d like, Murch is becoming a fan.

July 27, 2002, Murch’s Journal

More working with FCP: in a sketch-pad mode, understanding the clips, sequences, projects, etc. Navigating around the controls, which are good—sometimes very good—and sometimes just different and sometimes not as good (no asymmetric trimming). I am keeping a running list of things to send to Brian and Bill.

This dance between Murch and Apple, a tango of overlapping interests, will continue until Cold Mountain is finished. Coming as they do from two different worlds, the creative and the corporate, the editor and the computer company move in different rhythms. Walter is drawn to the Final Cut Pro application and is willing to use it, even in its present imperfect state. Apple looks at a high-profile project and wants to proceed cautiously, lest its new baby be running before it safely walks. Nevertheless, when Murch writes to Ramy back in Los Angeles about his exchange with Will Stein, he reveals an unwavering optimism, a belief that the natural symbiosis between Cold Mountain and Apple is self-evident and might still prevail.

Date: July 28, 2002

From: Walter Murch

To: Ramy Katrib

Will S. has opened the door a crack, and I am writing him today to tell him that I would like him (Apple) to work with DFT and give you what you need to proceed. Our main focus, as I outlined in my letter to Will, should be change lists and non-embedded OMF export (for sound files). I am happy with how this has all turned out—perhaps a month late, but the essential fact that we are in Bucharest and working with FCP on Cold Mountain, already two weeks into production, is a major “convincer” of the seriousness of our intent. Sydney Pollack just arrived today, and is happy that we are using FCP. He has it on his laptop.

Date: July 29, 2002

From: Walter Murch

To: Ramy Katrib

Jim Foreman [Aurora’s and DFT’s man in Bucharest] left this morning. All worked out very well and I think he enjoyed himself. We kept a clipping of his hair to bring near the hard drives and the CPUs if something begins to go wrong—a kind of editorial voodoo.

July 31, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Article in Herald Tribune about nerve systems. We have two: a thick fast fiber, giving us the ‘hard’ information about when, where, impact, etc. and another, thin slow fiber system giving us emotional information about the nature of the touch, love, etc. The signals for this second system are processed in the visual part of the cortex .

Don’t forget little people for the monitor here. Tomorrow.

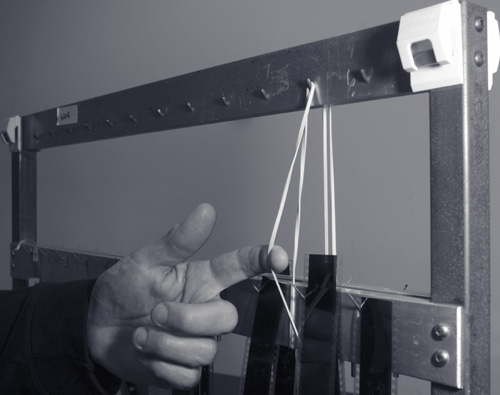

The “little people” are another one of Walter’s handmade edit room tools. These are paper cutouts in the shapes of a man and a woman that he affixes to each side of his large screening monitor. They are his way of dealing with the problem of scale.

Murch’s “little people” next to his viewing monitor remind him that this image will eventually be 13 feet tall.

As an editor, Murch must remember that images in the edit room are only 1/240 the square footage of what the audience will eventually see on a 30-foot-wide screen. The large TV Murch uses for viewing—the “client” monitor—is masked off to the proper aspect ratio, (the width 2.35 times the height in the case of CinemaScope, the wide-screen projection format for Cold Mountain). But it’s still easy to forget the size of projected film, which can trick an editor into pacing a film too quickly, or using too many close-ups—styles more akin to television. The eye rapidly apprehends the relatively small, low-detail images on a TV. Large-scale faces help hold the attention of an audience sitting in a living room with lots of distractions and ambient light. But in movies, images are larger than life and more detailed, so the opposite is true. The eye needs time to peruse the movie screen and take it all in. But for many months, except for projected film dailies, the film editor works at TV scale. The solution for Murch is to have these two human cutouts stand sentry on his monitor, reminding him of the film’s eventual huge proportions.

August 1, 2002, Murch’s Journal

August first—new month. Let it be blessed with good luck and productivity. Amen. Cutting “soldiers” tape.

Problems arise almost immediately as Murch begins to use Final Cut to actually begin editing footage on Cold Mountain. Never one to panic, he casually mentions this at the end of an email to Ramy, almost as an afterthought: “We are still getting the occasional stutter in the Canvas screen, so if you have any brainwaves in that department, let us know. All best wishes from Bucharest. Walter.” The Canvas is the screen in the FCP interface that shows the results of an edit. Those faltering images are annoying, even if the edited material isn’t itself flawed.

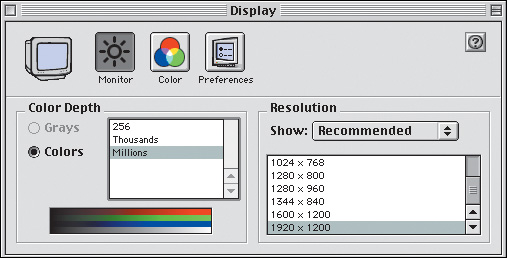

DFT and its network get to work searching for solutions to the stuttering image problem among software engineers, developers, and Final Cut users. The problem makes its way from Bucharest to Zed Saeed at DFT in Los Angeles and then to Michigan, headquarters for Aurora, the company that makes the Igniter add-on card for digitizing video into FCP. The issue turns out to be simple to resolve; it’s not unlike the set-up problems any computer user has with new equipment, setting preferences and defaults to work optimally with a system’s associated hardware and software. All computer monitors have settings for resolution (the size and density of the screen pixels), brightness, and color depth (number of colors). Aurora suggests that Jim Foreman, who is providing on-site tech support, reset the pixel resolution on Murch’s monitor and change the color depth to “thousands of colors” instead of “millions of colors.” That does the trick; the stutter goes away.

The Mac OS 9 Display control panel for setting numbers of colors for the monitor. Until Murch reset this to “thousands” he had problems with image stutter.

The next hurdle that shows up isn’t so easy to get over. Sean reports to Ramy that when Walter works with color-corrected digital video footage, he can’t get his preferred edit-on-the-fly technique to work accurately. If he taps the spacebar (stop), or the K or Enter keys (pause) while watching a scene play back on the monitor, the scene plays on for several frames, instead of stopping immediately. This negates Murch’s intuitive frame-marking method.

On July 30, Walt Shires weighs in on the problem of frame-accurate stopping with an email to Sean. The news isn’t good: “The problem you are referring to has been a common problem with FCP. There is a certain mount of CPU time necessary for FCP to process the keystroke for stop and then make the call to QuickTime to stop the video playback. I suspect that when working with real-time color correction the load on the CPU is causing the stop playback to occur later than usual. Unfortunately, there is really no way around it.” This function was one of Walter and Sean’s deal-breakers when they first went to see DigitalFilm Tree about Final Cut Pro. Murch continues working, however, bypassing the color-correction mode until it can be fixed at some later date. The telecine transfers of the film to video, done by a Romanian technician just down the hall at Kodak, are extremely good, and generally no extra color correction is needed. With confidence in Sean and DigitalFilm Tree, tolerance for the ups and downs of technology, and a deep-seated faith that things work out eventually, Murch is just satisfied to be underway.

August 2, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Finished the “soldiers” tape and put music on it, gave it to Huw [Cold Mountain liaison to the Romanian army]. My first cut sequence on FCP! worked out well Anthony viewed the tape, and liked it—“good to see some Walter cutting”—thought that the interaction between Oakley and Inman is an indication of how it will be. He liked the music—wondered if I had come upon that decision myself. I told him Dianne had told me what he was thinking.

Walter’s August 2 Journal entry reveals something very telling about relationships and communications within the Cold Mountain film community. Minghella is much admired and respected by his cast and crew, in part because he creates a working environment that is open, creative, and collegial. Many high-caliber people keep working with him—in front of and behind the camera—because Minghella encourages contributions from all quarters, and conversations about creative choices, which isn’t the rule among many film directors. The collaborative environment, his directorial sensibilities, and the kinds of material he finds attractive are reasons some of the best people in the film business stick with him on one film after another: cinematographer John Seale, costume designer Ann Roth, composer Gabriel Yared, top producers—and Walter Murch. Minghella encourages his film family to engage in crosstalk and to share ideas and information even if he’s not always aware of what’s under discussion.

Director of photography John Seale (behind the camera) on the set of Cold Mountain.

August 3, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Screening all unscreened material. Trying to catch up

Sean still needs to find a solution to the audio file conversion problem that arose before the Final Cut Pro systems arrived from Los Angeles. This bottleneck costs him precious hours syncing up sound in time for the next day’s screening of dailies. Ramy reports to Sean that he is trying to work something out with AVTransfer, the company in Australia. Sean writes back to Ramy, pleased that DFT is putting out another call for help on sound: “Thank you, thank you. We are in this weekend, catching up and lying low. Walter continues to be a happy camper, so at least we’re doing something right.”

Two unsolved problems remain with the Final Cut Pro workflow: 1) converting sound files from .wav format (required by the telecine in the Kodak lab) into a format that can be recognized by FCP and ProTools; and 2) Walter’s inability to get accurate results using his preferred edit-on-the-fly technique on color-corrected clips. Two longer-range problems are on the back burner: getting audio files from Final Cut Pro out to ProTools for sound editing; and getting reliable change lists to conform the 35mm picture when the film workprint is cut and recut over the course of post production.

On the other hand, by early August, the DVD authoring feature of Final Cut has been put into operation, and copies of the dailies are made into DVDs and sent to Anthony, Sydney Pollack, and the other producers. Minghella starts building a folder containing a disc with each day’s work. This means he can review shots anytime and anywhere using his PowerBook.

Murch works on the battle sequence.

A few days later, as the battle sequence Murch puts together reaches 16 minutes, he suspects another long-term problem may be lurking: FCP seems to have a hard time ingesting long sequences—a concern that came up in Los Angeles but was never fully tested. It’s taking over a minute for each version of the battle sequence to load into FCP. Since Murch is working with several versions at the same time, “that means 3-4 minutes of video prep as the FCP unit is firing up,” he writes Ramy. Is this a smoldering fire that might burst into flames? Will Final Cut be able to load a five-hour assembly when the time comes, three months from now?

On this basic function, Avid systems work on a completely opposite principle from Final Cut Pro. When Avid is loading a project, regardless of its length—an entire two-hour film, say—Avid only loads small sections of media, the idea being that Avid provides the editor with just the media he or she needs for the part of a show that is under construction. Normally an Avid editor adjusts this setting so the machine loads a single three- or four-minute chunk of digitized video and sound at a time. Within that section, operations such as edits, trims, saves, etc. happen quickly and efficiently. However, if he or she wants to jump to material that exists outside that short swatch, the Avid editor will have to wait on the machine. Final Cut Pro has no similar adjustable setting to control the amount of media the editor wants to load; it simply loads an entire sequence from beginning to end. Murch knows this is a structural problem that goes to the basic engineering of FCP that may eventually get fixed. So he asks Ramy, “Any procedural suggestions in the meantime?”

There is no immediate solution forthcoming from DFT, but Walter remains unruffled. In fact, he flies to Paris three days later to meet Aggie and celebrate their 37th anniversary over a four-day weekend. On Murch’s return, he learns that Mihai Bogdan, the Romanian driver assigned to the edit crew, has hepatitis. The whole edit group must get gamma globulin shots, on top of the anti-rabies vaccine recommended for Romania.

Murch was happy with Final Cut Pro’s jog wheel, which moves images backward or forward at varying speeds.

Murch gets back in contact with Ramy. Before reminding him about the FCP load-in problem, Walter delivers an upbeat report: “FCP performed very well. I am particularly happy with the jog wheel, which is the most ‘film-like’ digital scrolling device I have experienced. I can really convince myself that I am looking at film going backward and forward at various speeds.” But the problem of how FCP handles media has just cropped up in another function. When Murch performed a routine deletion—removing an unused empty soundtrack from his Timeline, the graphic representation for a sequence—and FCP took 45 seconds to execute the command. What was a smoke alarm is now a bell-ringer. Walter knows if such a simple action takes that much time (it doesn’t even involve actual digitized video material) he might be in for some really long waits once he tries to load hours of material into Final Cut’s memory.

Walt Shires follows up for DFT by email. He tells Murch that Final Cut Pro plays back an edited sequence by building a virtual movie (called a .moov) that is held in its memory cache, not written onto a hard drive. “You are right,” Shires writes, “the longer and more complex the edited sequence gets, the longer it will take to build the .moov. The length of time it takes to organize the .moov gets exponentially longer as the sequence gets more complex. Final Cut builds the whole movie at once so you can review any portion at any time.” One can feel Shire’s anxiety on Walter’s behalf: “There is a trade-off. Perhaps good, perhaps not. Hope your experience continues to be a good one. Walt.”

Romanian crew member Mihai Bogdan who was promoted from driver for the edit crew to syncing up dailies.

Murch appreciates Shire’s explanation, but he is blunt: “This is the one aspect of FCP that I have my eye on as being a potential troublemaker down the line—the [first assembly of the] film will eventually be over four hours long [over five, as it turns out]—the wait is going to become increasingly frustrating.” Murch says this issue is high on his list of “musts” for Apple to work out in subsequent FCP versions. It should be able to use buffers, like a computer printer, or an online media player, to absorb chunks of data and spool it out as needed. “Certainly,” Murch continues, “something as procedurally brainless as deleting an empty audio track should not take 45 seconds to accomplish. Otherwise, all is well. How are we moving on the change lists and OMF output fronts?”

Aside from fretting about the capacity of his editing system Murch must attend to standard editor’s duties: informing Anthony and the producers about “negative scratches—not too serious;” providing notes to help guide the chapel-building scene which is being re-shot due to weather; and an email to producer Bill Horberg about the lead actors. “Two worry beads for me: Ada’s accent (nasal, hard to understand, very few consonants) and Inman’s hat (not cool, like Oakley’s)—it makes him skulk, if worn too low on the brow, too Hobbit-like. A girl would wonder about a guy who wore a hat like that. And a guy would wonder about a girl with a voice like that. Hmm... I have talked to Anthony about these things.”

Anthony has a chat with the dialogue coach. Afterward, when he screens new dailies of Ada, Murch’s concerns about Kidman’s accent and speaking style are allayed. As for the hat Jude Law wears, Horberg writes, “Hats are Ann Roth’s domain—tread there at your own personal risk!!!”

August 16, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Finished the battle “work-in-progress” and sent it off to Anthony with the dailies. Let’s see what his reaction is. Screened some dailies to catch up. Need to screen two days worth each day at least to get up to speed. When will Sean be ready to give me more scenes I can cut!!

Murch is impatient. Although he has begun cutting the battle scene, he’s ready to do more. And footage is really beginning to accumulate. Getting started two weeks late is having its effect. The equipment from DigitalFilm Tree arrived safe and sound on July 15, the first day of principal photography. But in Murch’s ideal universe it should have been in Romania in time to be plugged in, tweaked, and operating—all set to go for first day of dailies. Sean Cullen later describes how restless Murch felt as Cullen put the system through all the necessary tests, methodically taking a piece of edited film through the entire system: “I still had to wring out the system and then wring out our workflow. This meant digitizing material, cutting a sample together on another machine (to simulate Walter’s), making tapes and outputting cut lists to check that the whole system would work in post. Walter got to see me cutting material together but he couldn’t start yet.” To allow Murch to begin editing something—the battle scene—Cullen gave him a series of one-hour QuickTime movie files. Each QuickTime movie represented one complete reel of film telecined to videotape. Even though these one-hour QuickTime files let Murch get started, it would turn out later that they were the cause of his frustration with the long load-in time he was now experiencing on Final Cut.

Assistant Sean Cullen preparing digitized film footage for Murch to cut.

Up in Brasov, on the set, Minghella looks at the DVD on his laptop with the battle scene Murch has edited. He sends an email:

Date: 8/17/02 9:14 PM

From: Anthony Minghella

To: Walter Murch

Thanks, Walter

just had some time to look at the battle sequence, for which many thanks. It has, of course, your beautiful taste and touch, and is encouraging. I hate myself, as you would expect, and my failings, and I also see how much we will have to do to get the sequence right, and how much I have ahead to make the film work between that stuff and what I’m doing now. I can’t really look at it now with a sane eye, and - naturally - mourn what isn’t there yet as much as I do what is already there, with its frailties. But I also can’t wait to stop collecting the material and sit with you in Hampstead and begin the fun.

thanks, dear friend

from rainy Brasov

ant

Cullen’s workflow for getting shot film onto Murch’s desktop for editing.

“Anthony sent a sad email after looking at the sketch of the battle,” Walter writes in his Journal on August 18. “I thought somewhere it would make him happy, but it just seemed to depress him more.”

If Murch’s spirit is dampened by Minghella’s response, it doesn’t last long. The next day Sean solves the problem with loading media. On advice from DFT—“Don’t put your entire project in one FCP file”—Sean breaks the media down into bite-sized pieces for Final Cut Pro to digest.

August 19, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Hooray! Clips are in FCP. And when a sequence is opened up, it does so 150 times faster. An hour-long sequence opens in two seconds as opposed to four minutes. Why? Probably because the sequence is assembling from short clips of shots rather than long clips of tapes. A huge relief, that it functions so well now—that was a thundercloud bearing down on me as I thought of the problems further along in the process.

“This was a huge turning point, in retrospect,” Murch says afterward. “It wouldn’t have been possible to keep going if it hadn’t worked out this way.” Without this workaround, Murch would be waiting longer and longer—up to a half hour or more—for his project to load into Final Cut Pro as the assembly grew in size. That kind of delay would be unacceptable in the rush to finish a major motion picture.

The problem with large amounts of media and Final Cut Pro wasn’t an issue on previous feature films, such as The Rules of Attraction and Full Frontal, because, according to Ramy, “they got used to it.” As with many off-the-shelf features in FCP, editors simply accept the default settings, so to speak. But Murch wasn’t going to be satisfied waiting on the equipment. Sean ran with DFT’s suggestion by making separate QuickTime movies for each “flash-to-flash” take. These are discrete camera takes marked at the beginning by one or two frames of unusable bright images when the camera starts. The motor isn’t yet up to speed, so the film gets overexposed for a brief moment. A similar bright flash occurs at the end of a take when the camera is turned off and two or three frames of film are overexposed as the motor slows to a stop. By using a QuickTime movie for each flash-to-flash segment, and then linking all the adjacent QuickTime movies back together, FCP could play them seamlessly. The whole equaled its parts. Walter’s faith is rewarded after all. There was a better method for loading media; it was just a matter of discovering it.

Murch had started projecting the total amount of footage to expect on Cold Mountain one week after principal photography began. His yardstick then was the average length of each take compared to its projected length when those script pages were read aloud. At that point, take timing exceeded read-script timing by an expansion factor of 1.38. He projected the first assembly to be just over 3½ hours.

Now, four weeks later, Murch can use a more precise tool to make his estimate—an expansion factor that uses the relationship between the timing of an edited scene and the timing of that scene when it was read aloud.

August 20, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Scene 12 all cut together is 144 seconds long, or exactly twice what it timed out at. So the first assembly of this film could be five and a half hours long. Read this in five months and tell me what happened.

For Murch, this is further proof that Cold Mountain is going to have a long first assembly—longer than either English Patient or The Talented Mr. Ripley. He had hoped that after the first three weeks of filming the 12-camera action scenes of the Battle of the Crater, Cold Mountain’s expansion factor would shrink as Minghella moved into more conventional dialogue scenes. But the early indications are that this is not happening: the expansion rate stays the same.

This means that the assembly will most likely be over five hours, and that consequently the 30 percent barrier—and its implications of open-heart surgery—will indeed have to be crossed somewhere down the line in London, during editing.

The ultimate scheduling question is: Can he and Minghella get the film edited in time for a Christmas, 2003 release? But the high expansion rate has short-term consequences as well. Can the assistants prepare dailies for Minghella and the producers on a timely basis? Does Murch have enough time to screen and take notes on all the footage? Will he be able to prepare a first assembly by the time production wraps in mid-December? With all these demands, will Murch also be able to have a creative connection with the material so he can adequately advise Minghella about story or character issues while still in production?

The question of keeping up with the amount of shot footage, and the inevitability of crossing the 30 percent threshold both lie on top of the fact that Murch, Cullen, and DigitalFilm Tree have just shaken out a new editing platform with several key functions that are still unproven. That should certainly be enough. But there are other, more unwelcome surprises.

August 27, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Driver crashed on way back from Brashov and the negative scattered all over the road. All ok, though—the cans didn’t open up.

To be followed by agreeable arrivals.

August 30, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Aggie arrives today she is just getting on the plane as I write this!

Aggie arrived! At 6.30—great to see her—she brought gifts for everyone (tea and Marmite) and everyone loved to see her. Especially me.

At the end of August, the Cold Mountain production moves to North Carolina for three weeks to shoot various scenes there: Inman’s walk from sea to mountains; the hospital and the peanut seller; Veaseytown; the ferry crossing; and Veasey’s discovery of the saw. Murch and the edit crew stay in Romania, so this is a chance to get caught up with logging, digitizing, and other housekeeping duties, since it will be two weeks before dailies footage from the U.S. arrives in Bucharest.

Minghella sends Murch an email report from the U.S.:

Date: 9/2/02 4:04 PM

From: Anthony Minghella

To: Walter Murch

Subject: Charleston

...where, apparently, the drought they’re suffering is about to be solved by a huge tropical storm! I am plagued.

Happy to get some dailies on DVD although they don’t all play well. Kiss interrupted by skipping disk.

[Cold Mountain author Charles] Frazier saw some stuff and seemed cheered.

Should I try and get a close-up of Butcher lying dead on the ground in the night raid? He lives in Charleston.

Having a free day here for Labor Day after an interminable journey immediately followed by a day’s scouting. Relentless.

Very prone to depression on this movie. Which was also the case shooting The English Patient. What is it? Why is it? Just tired, I suppose. But trying to find a way to take pleasure from the challenge of collecting the material and not just to be ground down.

Love to you. Very glad you’re out there helping

xa

From: Walter Murch

Subject: Re: Charleston

Date: 9/2/02 4:41 PM

To: Anthony Minghella

Caro Ant:

Coraggio! The material is going together very well. Aggie was here over the weekend and very moved and impressed with what she saw. Muriel and Ann as well.

The coming into the world of the new is never easy because there are no guidelines.

The Furies are jealous of such beauty and attack with weather.

KYPU

Etc.

or as Stein put it in “Lord Jim”:

“A man that is born falls into a dream like a man who falls into the sea. If he tries to climb out into the air as inexperienced people endeavor to do, he drowns—nicht wahr? ... No! I tell you! The way is to the destructive element submit yourself, and with the exertions of your hands and feet in the water make the deep, deep sea keep you up. So if you ask me—how to be? ... I will tell you! ... In the destructive element immerse.”

Butcher ... Hmm ... You could, but I think a wild line would do more to identify him. In the hurry of escaping, and him on the ground at night, I don’t think that we would know who we were looking at.

Your pal in Bucharest,

W. xox

September 2, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Sad email from Ant about woes—tropical storm Edouard is on its way to meet them.

Just then, an unexpected producing crisis strikes that will demand Murch’s attention. Whether for its own financial reasons or because of the size of the total budget, MGM pulls out of its financing deal for Cold Mountain. Miramax, left holding a half-empty bag, needs to find a partner with $40 million to complete the movie.

September 10, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Anthony wants to make a demo DVD of key scenes from the film for extra financing. Can I do this somehow in the time available? Can you give me help?

Origins of the Cold Mountain Project

Cold Mountain originated as a United Artists/MGM motion picture. The initial producers, Ron Yerxa and Albert Berger (Bona Fide Productions), took the book to Mirage Enterprises, the company partnered by Sydney Pollack and Minghella, for Pollack to consider directing. Pollack wanted Minghella to direct. The two entities connected with Lindsay Doran at United Artists/MGM, who’d worked with Pollack on previous pictures. Meanwhile Cold Mountain had become a best-seller and a hot property. The Bona Fide/Mirage/United Artists group bid for the film rights in an auction among several producers, including actor Brad Pitt’s company. Author Charles Frazier liked what Minghella said in their phone conversation about how he’d adapt and realize the novel for screen, and the Bona Fide/Mirage group won the rights with their $1.5 million offer. Harvey Weinstein, Miramax co-chairman, loved the story and the screenplay, so Miramax Films came on as a co-producing distributor, committing itself to 50 percent financing of the $80 million project. All was going along as planned until MGM executives decided that weather conditions and other difficulties were sending costs uncontrollably higher, and backed out.

Murch and Minghella had been through this kind of thing before. It’s not that unusual for major studio films, like their low-budget independent cousins, to have last-minute fiscal crises. Minghella’s first picture with Miramax, The English Patient, started off with just such drama. Fox Studios put up production financing after producer Saul Zaentz had developed the project to the takeoff point. As crew and cast were assembling in Italy, and sets were being built, Fox got cold feet and pulled out. Minghella asked the cast and crew not to leave, he was that confident in the project’s viability. Minghella and Zaentz quickly shopped the project around, got Harvey Weinstein to put up the $30 million budget, and Minghella was shooting two weeks later.

The only benefit of MGM pulling out of Cold Mountain at this late date is there is some film footage in the can, and it can be shown to attract interest. So Miramax, through Minghella, asks Murch to cut together a promotional sequence—a selling tool with sample scenes to attract a new studio partner. Murch gets right to work and makes another footage calculation:

September 11, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Estimate Length:

Of the scenes I have cut together so far, forgetting the battle = 34.45

These were estimated to be = 18.14

So expansion rate = 1.9

For an estimated 2.48 length x 1.9 = 5.20.

Five hours and twenty minutes.....

How can I best break the news to Anthony? For I must...

One week later Murch completes the first draft of a 25-minute sample sequence on DVD. And with a memo to the files he reminds himself about taking useful editing notes—never to forget that lesson of rediscovering the alternate line reading, “He’d kill us if he had the chance,” from The Conversation.

September 20, 2002, Murch’s Journal

In taking editing notes the skill is to think that every line reading might have a context in which it could be good. Imagine the cuts, and the good might lie right next to the bad. Don’t under any circumstances write off a take as being throughout no good. If you must, then say WHY it is no good. This sharpens your perception as well as being a good reference later on.

Murch put scenes together in conjunction with each other for the first time in cutting the sample DVD. Now, by editing actual scenes, the expansion factor is no longer theoretical. How will he ever bring the film in with a releasable running time? Working under the stress of a deadline to finish the sample DVD, Murch gets more comfortable with Final Cut Pro, and like Minghella and the producers, also contemplates wholesale scene removals.

September 22, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Left eye seeing double.

Where can script be cut: Inman start on his journey faster, and the area around Maddy, Junior redux, Sarah. Sarah could go if you were being brutal. Feel more and more comfortable with Final Cut, especially since QuicKeys can work with it. Make more use of duplicated keys and the f keys.

“Junior redux” is a scene Minghella added to the screenplay late in the game. On his journey back to Cold Mountain Inman meets up with Reverend Veasey (Phillip Seymour Hoffman). The two fugitives take shelter with Junior, a backwoods moonshiner with questionable motives and a house full of sirens. Junior uses these available women to lure Inman and Veasey into his trap: turning Inman and Veasey over to the Home Guard for a bounty. In the added scene, Inman returns to Junior’s farm after his encounter with Maddy, and kills Junior in revenge, retrieving his LeMats pistol and the book Ada gave him. Faced with the fact that the first assembly is likely to be over five hours long, with all the attending financial, scheduling, and editing consequences, Minghella decides to abandon the Junior killing scene, and it is not filmed.

Meanwhile, executives at Miramax see the DVD with the sample scenes and send word back to Murch through producer Bill Horberg that they are happy. Already there is a feeling at the studio that Renée Zellweger’s performance as Ruby is dazzling, that she will be an important element in the film’s success, and that Murch should adjust the sample reels accordingly.

September 25, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Anthony came to cutting rooms [on his return from filming in the US] and liked what he saw—the cut footage and the facility. A refuge. He thought that I had put together a lot of stuff, despite that it seems to me that I haven’t. That funny perspective we have of what we do. Anthony finishes each day thinking that he hasn’t gotten anything—I remember it well from Return to Oz.

October 5, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Call from Bill H. about Tape for MMX. They want to include more Renée and have less battle, keep it at 25 minutes. He said Anthony would phone.

At last, the Final Cut Pro system is running smoothly. The hardware, software, and workflow hums along; footage from the North Carolina shoot is screened and logged; the DVD demo is out the door; Murch can breathe relatively easy for the moment. It’s a good time to introduce an innovation made possible only by virtue of Final Cut Pro: giving assistants a chance to do some real editing.

October 6, 2002, Murch’s Journal

A scene for everyone to cut: put them to work! Now that we have almost caught up.

Up until the early 1970s, when film editors began switching from upright Moviolas to flatbed Steenbecks and KEMs, assistants worked in closer proximity with their editors—more like apprentices at their sides. But new editing systems began to push apprentices out the door, literally. An editor no longer needed an assistant right there, handing up film rolls and filing trims. Gone, too, was the chance for an assistant to learn the craft by watching and participating in editing moment by moment. The move to Avid accelerated the process of estrangement. Assistants began to work at their own edit stations doing file management, or on the film conform bench, away in other rooms. Murch seizes on Final Cut Pro’s inherent pluralism to make film editing more accessible. “Another upward twist of the spiral,” as he puts it.

October 11, 2002, Murch’s Journal

The guys have installed FCP on their machines and are getting ready to start cutting. Sean is helping them and they are excited.

Murch seems to be in the zone. There’s joy in the work, being fully engaged, pushing the technical limits. He’s signing emails to Ramy: “Narok!! Valter Murcescu.”

Assistant editors before biking to work on Cold Mountain in Bucharest.