Game Features

In order for the story to progress and the characters to develop, the characters have to have something to do; therefore, exploring and combat make up a big part of most CRPGs. In most such games, the stories and challenges are prescripted, so the player experiences the same things each time he plays. In a few cases, individual levels are randomized on each play, which makes the games more replayable—the Diablo series is a well-known example.

Themes

CRPGs generally allow the player to experience a pivotal role in solving some hugely important problem. The premise of most role-playing games can be summed up in the statement “Only YOU can save the world!”—or the tribe or city or whatever level of society is threatened. However, saving the world is a cliché, an adolescent power fantasy that has been terribly overused in this genre. Consider some alternative quests that could have a secondary consequence of saving the world but need not:

• Find and punish the person responsible for a loved one’s murder.

• Learn the secret behind your hidden parentage.

• Rescue the kidnapped princess/prince.

• Find and reassemble the long-lost pieces of the magic object.

• Destroy the dangerous object.

• Find the evidence that will exonerate you from a false accusation.

• Transport the valuable object past the people trying to seize it.

• Try to get home after having been abducted.

While these are all very familiar themes, at least they’re not specifically about saving the world.

Progression

RPGs almost always tell a story, characterized as a long quest in pursuit of some important goal. The quest is broken down into a number of episodes that progress in a linear sequence, each with its own subquest and major challenge at the end. These end-of-episode challenges (almost always combat with a powerful enemy) are analogous to the boss characters at the ends of levels in action games. The story maps onto exploration—a journey, in other words—and each episode takes the player to a new location. Unlike in linear games, such as rail-shooters or side-scrollers, it’s often possible to go back to a previously visited location, though there may no longer be anything worthwhile to do there. A few games take the party back to a previously visited location for a new episode; when they do this, it’s often markedly different when they return. For example, in Planescape: Torment, the town of Curst is destroyed while the party is away.

In order to progress from one episode to the next, the player’s party has to have enough strength to overcome whatever major challenge lies at the end of the current episode. This won’t be possible right away (even if the player knows where the challenge is), so the activities during the chapter help the characters to grow strong enough.

Because the story of the game is intimately bound up with the game world itself, the section “The Game World and Story,” later in this book, addresses storytelling in CRPGs.

In addition to the quests that lie along the main storyline, there are also optional side quests that are unrelated to the main ones. These are not thrust upon the player but must be sought out. Visible or audible cues inform the player that one of the NPCs in the game has a problem that the party can help solve; if the party goes up and talks to her, the player learns of the side quest and can choose to accept or reject it. Normally there’s no penalty for refusing one apart from the missed opportunity to have another adventure and earn some more experience. Players can usually abandon a side quest without penalty as well.

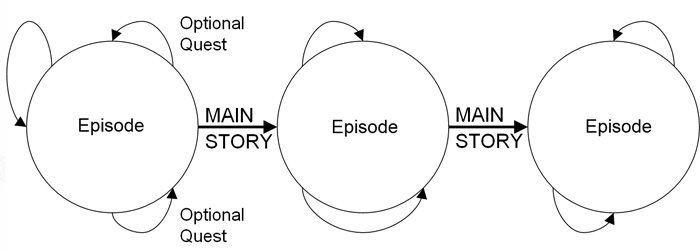

Side quests seldom carry over from episode to episode. (If a quest does so, it’s usually related to the main story rather than being a side quest.) Figure 1 illustrates the general progression of a CRPG.

Figure 1 Typical CRPG progression

Gameplay Modes

Because CRPGs try to duplicate (within limits) the flexibility of tabletop role-playing games, they offer more kinds of activities than any other genre. Among these activities are exploration, tactical combat, stealth operations, conversation, buying and selling, and inventory management.

Typically CRPGs use four major gameplay modes and a variable number of minor ones. The major modes are exploration and combat, conversation, trade, and inventory or equipment management. The minor modes are character creation (used only at the beginning of the game), character appearance, and upgrade screens and skill tree management. The next four sections describe the major modes briefly.

Exploration and Combat

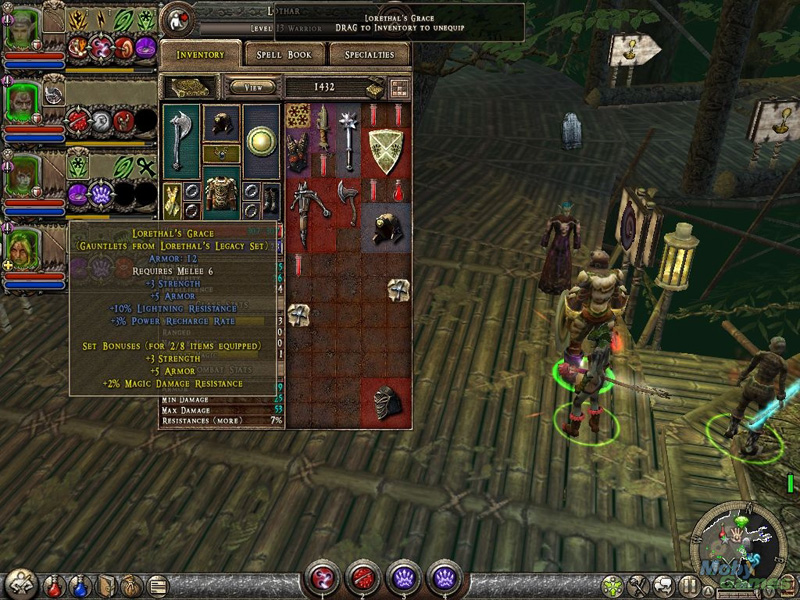

In older computer games, exploration was often a gameplay mode separate from combat, and the two modes had different camera models. Modern games combine them into a single mode. Traditional party-based RPGs often use an isometric perspective so the player can see the whole party. Figure 2 is from Baldur’s Gate II: Throne of Bhaal, which illustrates an isometric perspective.

Notice the complexity of the user interface, with buttons along three sides of the screen as well as a scrolling text window at the bottom.

Figure 2 Baldur’s Gate II: Throne of Bhaal with an isometric perspective showing several party members as well as a number of NPCs

If the game has only one player character, first- or third-person perspectives are common; see the section “Camera Model,” later in this e-book.

The actions available in the exploration and combat mode include selecting one or more characters in the party, setting a formation in which they will move together, designating a location for them to walk or run to, designating NPCs for them to attack or to talk to, picking up objects, and exercising special skills such as casting magic spells or searching for traps. The buttons to the lower right in Figure 2 are for setting a formation.

Conversation

Conversation modes often use the same perspective on the game world as the exploration and combat mode but replace the exploration- and combat-related user interface features with a dialogue-display mechanism. Occasionally, they switch the perspective to a close-up view of the other character in the conversation or display the character in a pop-up window.

CRPGs almost always manage conversations via dialogue trees, a mechanism that is described in detail in the book Fundamentals of Game Design, Third Edition (Chapter 11, “Storytelling”). The player selects an NPC in the game world to speak to. A window opens, presenting a list of things that the avatar can say to the NPC. The player chooses one, and depending on what her choice is, the NPC replies, sometimes in text but often with an audio recording as well. Sometimes a scrolling window records the content of the conversation so that the player can go back and see what was said for as long as the conversation continues, or it may be recorded in a log or journal the player can bring up later. Asking the right questions or saying the right things elicits useful information from the NPC and sometimes gains experience points for the player as well.

Figure 3 shows a conversation in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. The camera model is first-person, and the person the player is speaking to is in the foreground. Her name appears beside her, and what she has just said appears across the bottom. The player’s menu of possible responses is at the right, with an icon to indicate the one currently selected.

Conversations almost always take place between the avatar character and just one other person. Conversations with more than one person become complicated because the dialogue window must indicate to whom each statement is addressed.

Figure 3 The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim conversation

Trade

Any buying or selling of items in the game takes place in a specialized trading mode. Most games in this genre have towns or settlements with friendly NPCs—blacksmiths, healers, and so on—who run businesses that offer to buy or sell goods and services. MMORPGs often have auction houses at which players can sell items to other players, too. The interface is similar to the conversation mode interface, with a view of the shop, sometimes an image of the person the avatar bargains with, and a list or a set of images of all the available items. Tom Nook’s store in the Animal Crossing games is a good example. The player can choose to buy an item or sell an item he already owns to get more money and can often bargain with the shopkeeper. Items purchased go directly into the avatar’s inventory.

Inventory

The inventory mode lets the player manage the objects that a given character is carrying around. Because CRPGs tend to include large numbers of objects, players need a system for keeping track of them and trading them among characters.

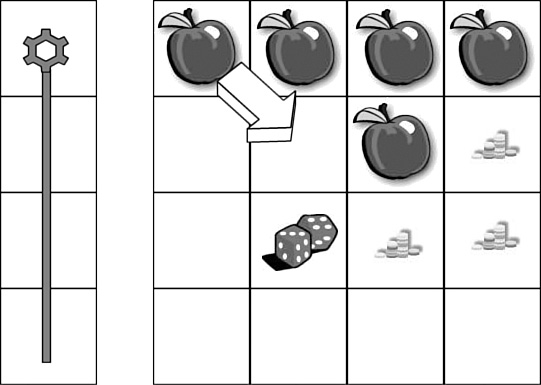

It’s not realistic to simulate the actual packing of items into a backpack, and in any case, most games allow characters to carry more than would be credible if they were real people. Instead, a typical solution is to divide the character’s carrying capacity into an array of boxes. Each box can carry one type of item. Large items take up several adjacent boxes. If an item is small enough, a single box can store several of them, up to some maximum limit; this is called stacking. Usually a little number appears on top of the item to indicate how many are stacked there. Figure 4 shows the inventory mode for Dungeon Siege II, which appears as a pop-up window over the main game world.

Figure 4 The inventory mode in Dungeon Siege II

Item weight may be a secondary constraint. No matter how many boxes the player has free, her character can carry around only so many lead weights. The BioWare games assess a penalty on a character’s speed if she is carrying more than a certain weight, and above another threshold the character cannot move at all. Money and clothing are often exempt from the weight limit. Some games, such as World of Warcraft, provide places where the player can safely store some of her inventory; these are often characterized as banks or as the player’s house.

The player can spend a disproportionate amount of time micromanaging the contents of the inventory, so inventory management becomes disproportionately important. Often, this task breaks a cardinal rule of human-computer interaction: Don’t force the player to perform a menial task best handled by the computer. Figure 5 illustrates a problem with systems that allow an object to take up more than one box in the inventory: To put a staff in, the player must first move an apple out of the way, a trivial problem but one that there’s little reason to make the player deal with. A simpler solution is to display a simple table of the items in the inventory, without requiring the player to organize them in space. A pair of indicators, one for the total weight of the inventory and one for the total volume, could tell the player how much room she has left and how much more weight she can carry.

Figure 5 This inventory design requires the player to shuffle objects around.