4

Product and Portfolio Management

Introduction

Effective marketing comes from customer knowledge and an understanding of how a product fits customers’ needs. In this chapter, we describe metrics used in product strategy and planning. These metrics address the following questions: What volumes can marketers expect from a new product? How will sales of existing products be affected by the launch of a new offering? Is brand equity increasing or decreasing? What do customers really want, and what are they willing to sacrifice to obtain it?

We start with a section on trial and repeat rates, explaining how these metrics are determined and how they’re used to generate sales forecasts for new products. Because forecasts involve growth projections, we then discuss the difference between year-on-year growth and compound annual growth rates (CAGR). Because growth of one product sometimes comes at the expense of an existing product line, it is important to understand cannibalization metrics, which reflect the impact of new products on a portfolio of existing products.

Next, we cover selected metrics associated with brand equity—a central focus of marketing. Indeed, many of the metrics throughout this book can be useful in evaluating brand equity. Certain metrics, however, have been developed specifically to measure the “health” of brands. This chapter discusses them.

Although branding strategy is a major aspect of a product offering, there are others, and managers must be prepared to make trade-offs among them, informed by a sense of the “worth” of various features. Conjoint analysis helps identify customers’ valuation of specific product attributes. Increasingly, this technique is used to improve products and to help marketers evaluate and segment new or rapidly growing markets. In the final sections of this chapter, we discuss conjoint analysis from multiple perspectives.

|

Metric |

Construction |

Considerations |

Purpose |

4.1 |

Trial |

First-time users as a percentage of the target population. |

Distinguish “ever-tried” from “new” triers in current period. |

Measure whether sales eventually rely less on trial and more on repeat purchasers. |

4.1 |

Repeat Volume |

Repeat buyers, multiplied by the number of products they buy in each purchase, multiplied by the number of times they purchase per period. |

Depending on when trial was achieved, not all triers will have an equal opportunity to make repeat purchases. |

Measure the stability of a brand franchise. |

4.1 |

Penetration |

Users in the previous period, multiplied by repeat rate for the current period, plus new triers in the current period. |

The length of the period affects norms—that is, more customers buy in a year than in a month. |

Measure the population buying in the current period. |

4.1 |

Volume Projections |

Combine trial volume and repeat volume. |

Adjust trial and repeat rates for time frame. Not all triers will have time or opportunity to repeat. |

Plan production and inventories for both trade sales and consumer off-take. |

4.2 |

Year-on-Year Growth |

Percentage change from one year to the next. |

Distinguish unit and dollar growth rates. |

Plan production and budgeting. |

4.2 |

Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) |

Ending value divided by starting value to the power of 1/N, in which N is the number of periods. |

May not reflect individual year-on-year growth rates. |

Average growth rates over long periods. |

4.3 |

Cannibalization Rate |

Percentage of new product sales taken from existing product line. |

Market expansion effects should also be considered. |

Account for the fact that new products often reduce the sales of existing products. |

4.3 |

Fair Share Draw |

Assumption that new entrants in a market capture sales from established competitors in proportion to established market shares. |

May not be a reasonable assumption if there are significant differences among competing brands. |

Generate an estimate of sales and shares after entry of new competitor. |

4.4 |

Brand Equity Metrics |

Numerous measures, such as Conjoint Utility Attributed to Brand. |

Metrics tracking essence of brand may not track health and value. |

Monitor health of a brand. Diagnose weaknesses, as needed. |

4.5 |

Conjoint Utilities |

Regression coefficients for attribute levels derived from conjoint analysis. |

May be function of number, level, and type of attributes in study. |

Indicate the relative values that customers place on attributes of which product offerings are composed. |

4.6 |

Segment Utilities |

Clustering of individuals into market segments on the basis of sum-of-squares distance between regression coefficients drawn from conjoint analysis. |

May be function of number, level, and type of attributes in conjoint study. Assumes homogeneity within segments. |

Use customer valuations of product attributes to help define market segments. |

4.7 |

Conjoint Utilities and Volume Projection |

Used within conjoint simulator to estimate volume. |

Assumes awareness and distribution levels are known or can be estimated. |

Forecast sales for alternative products, designs, prices, and branding strategies. |

4.1Trial, Repeat, Penetration, and Volume Projections

Purpose: To understand volume projections.

When projecting sales for relatively new products, marketers typically use a system of trial and repeat calculations to anticipate sales in future periods. This works on the principle that everyone buying the product will either be a new customer (a “trier”) or a repeat customer. By adding new and repeat customers in any period, we can establish the penetration of a product in the marketplace.

It is challenging, however, to project sales to a large population on the basis of simulated test markets or even full-fledged regional rollouts. Marketers have developed various solutions to increase the speed and reduce the cost of test marketing, such as stocking a store with products (or mockups of new products) or giving customers money to buy the products of their choice. These simulate real shopping conditions but require specific models to estimate full-market volume on the basis of test results. To illustrate the conceptual underpinnings of this process, we offer a general model for making volume projections on the basis of test market results.

Construction

The penetration of a product in a future period can be estimated on the basis of population size, trial rates, and repeat rates.

Trial Rate (%): The percentage of a defined population that purchases or uses a product for the first time in a given period.

First-Time Triers in Period t (#): The number of customers who purchase or use a product or brand for the first time in a given period.

From penetration, it is a short step to projections of sales.

Simulated Test Market Results and Volume Projections

Trial Volume

Trial rates are often estimated on the basis of surveys of potential customers. Typically, these surveys ask respondents whether they will “definitely” or “probably” buy a product. As these are the strongest of several possible responses to questions of purchase intentions, they are sometimes referred to as the “top two boxes.” The less favorable responses in a standard five-choice survey include “may or may not buy,” “probably won’t buy,” and “definitely won’t buy.” (Refer to Section 2.7 for more on intention to purchase.)

Because not all respondents follow through on their declared purchase intentions, firms often make adjustments to the percentages in the top two boxes in developing sales projections. For example, some marketers estimate that 80% of respondents who say they’ll “definitely buy” and 30% of those who say that they’ll “probably buy” will in fact purchase a product when given the opportunity.1 (The adjustment for customers following through is used in the following model.) Although some respondents in the bottom three boxes might buy a product, their number is assumed to be insignificant. By reducing the score for the top two boxes, marketers derive a more realistic estimate of the number of potential customers who will try a product, given the right circumstances. Those circumstances are often shaped by product awareness and availability.

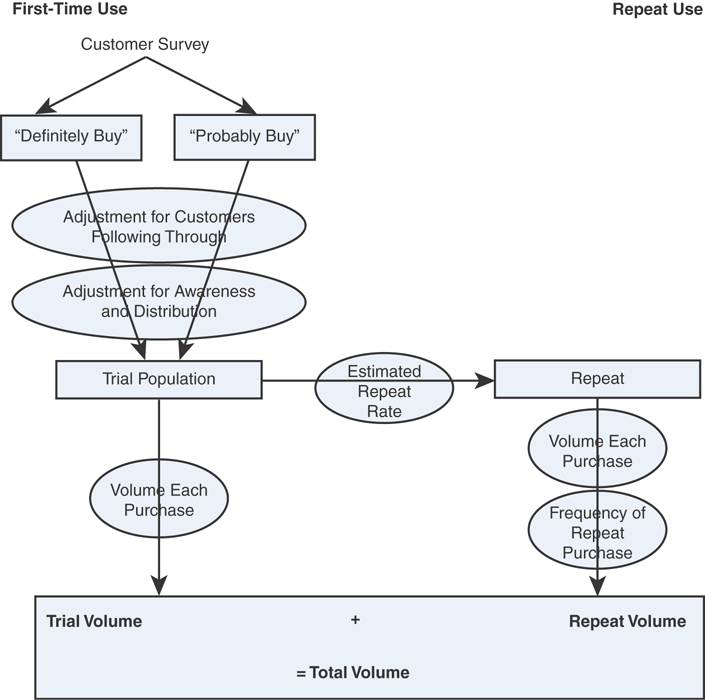

Awareness Sales projection models include an adjustment for lack of awareness of a product within the target market (see Figure 4.1). Lack of awareness reduces the trial rate because it excludes some potential customers who might try the product but don’t know about it. By contrast, if awareness is 100%, then all potential customers know about the product, and no potential sales are lost due to lack of awareness.

Figure 4.1 Schematic of Simulated Test Market Volume Projection

Distribution

Another adjustment to test market trial rates is usually applied: accounting for the estimated availability of the new product. Even survey respondents who say they’ll “definitely” try a product are unlikely to do so if they can’t find it easily. In making this adjustment, companies typically use an estimated distribution, a percentage of total stores that will stock the new product, such as ACV % distribution. (See Section 7.1 for further detail.)

Adjusted Trial Rate (%) = Trial Rate (%) * Awareness (%) * ACV (%)

After making these modifications, marketers can calculate the number of customers who are expected to try the product, simply by applying the adjusted trial rate to the target population.

Trial Population (#) = Target Population (#) * Adjusted Trial Rate (%)

Estimated in this way, trial population (#) is identical to penetration (#) in the trial period.

To forecast trial volume, multiply trial population by the projected average number of units of a product that will be bought in each trial purchase. This is often assumed to be one unit because most people will experiment with a single unit of a new product before buying larger quantities.

Trial Volume (#) = Trial Population (#) * Units per Purchase (#)

Combining all these calculations, the entire formula for trial volume is

Repeat Volume

The second part of projected volume concerns the fraction of people who try a product and then repeat their purchase decision. The model for this dynamic uses a single estimated repeat rate to yield the number of customers who are expected to purchase again after their initial trial. In reality, initial repeat rates are often lower than subsequent repeat rates. For example, it is not uncommon for 50% of trial purchasers to make a first repeat purchase but for 80% of those who purchase a second time to go on to purchase a third time.

Repeat Buyers (#) = Trial Population (#) * Repeat Rate (%)

To calculate the repeat volume, the repeat buyers figure can then be multiplied by an expected volume per purchase among repeat customers and by the number of times these customers are expected to repeat their purchases within the period under consideration.

This calculation yields the total volume that a new product is expected to generate among repeat customers over a specified introductory period. The full formula can be written as

Total Volume

Total volume is the sum of trial volume and repeat volume, as all volume must be sold to either new customers or returning customers.

Total Volume (#) = Trial Volume (#) + Repeat Volume (#)

To capture total volume in its fully detailed form, we need only combine the previous formulas.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Sales projections based on test markets will always require the inclusion of key assumptions. In setting these assumptions, marketers face tempting opportunities to make the assumptions fit the desired outcome. Marketers must guard against that temptation and perform sensitivity analysis to establish a range of predictions.

Relatively simple metrics such as trial and repeat rates can be difficult to capture in practice. Although strides have been made in gaining customer data—through customer loyalty cards, for example—it is often difficult to determine whether customers are new or repeat buyers.

When considering awareness and distribution, keep in mind that assumptions concerning the level of public awareness to be generated by launch advertising are fraught with uncertainty. Marketers are advised to think about what sort of awareness the product needs and what complementary promotions can aid the launch.

Trial and repeat rates are both important. Some products generate strong results in the trial stage but fail to maintain ongoing sales. Consider the following example.

Repeating and Trying

Some models assume that customers, after they stop repeating purchases, are lost and do not return. However, customers may be acquired, lost, reacquired, and lost again. In general, the trial-repeat model is best suited to projecting sales over the first few periods. Other means of predicting volume include share of requirements and penetration metrics (refer to Sections 2.4 and 2.5). Those approaches may be preferable for products that lack reliable repeat rates.

|

Market Size |

Penetration Share |

Share of Requirements |

Usage Index |

Market Share |

Units Sold |

New Product |

1,000,000 |

5% |

80% |

1.2 |

4.8% |

48,000 |

Source |

Estimated |

Estimated |

Estimated |

Estimated |

Penetration Share * Share of Requirements * Usage Index |

Share * Market Size |

Related Metrics and Concepts

Ever-Tried: This is slightly different from trial in that here it measures the percentage of the target population that has “ever” (in any previous period) purchased or consumed the product under study. Ever-Tried is a cumulative measure and can never add up to more than 100%. Trial, by contrast, is an incremental measure. It indicates the percentage of the population that tries the product for the first time in a given period. Even here, however, there is potential for confusion. If a customer stops buying a product but tries it again six months later, some marketers will categorize that individual as a returning purchaser, and others will categorize that individual as a new customer. By the latter definition, if individuals can “try” a product more than once, then the sum of all “triers” could equal more than the total population. To avoid confusion, when reviewing a set of data, it’s best to clarify the definitions behind it.

Variations on Trial: Certain scenarios reduce the barriers to trial but entail a lower commitment by the customer than a standard purchase.

Forced Trial: No other similar product is available. For example, many people who prefer Pepsi-Cola have “tried” Coca-Cola in restaurants that only serve the latter and vice versa.

Discounted Trial: Consumers buy a new product but at a substantially reduced price.

Forced and discounted trials are usually associated with lower repeat rates than trials made through volitional purchase.

Evoked Set: The set of brands that consumers name in response to questions about which brands they consider (or might consider) when making a purchase in a specific category. The Evoked Set for breakfast cereals, for example, is often quite large, while for coffee it may be smaller.

Number of New Products: The number of products introduced for the first time in a specific time period.

Revenue from New Products: Usually expressed as the percentage of sales generated by products introduced in the current period or, at times, in the most recent three to five periods.

Margin on New Products: The dollar or percentage profit margin on new products. This can be measured separately but does not differ mathematically from margin calculations.

Company Profit from New Products: The percentage of company profits derived from new products. In working with this figure, it is important to understand how “new product” is defined.

Target Market Fit: Of customers purchasing a product, target market fit represents the percentage who belong in the demographic, psychographic, or other descriptor set for that item. Target market fit is useful in evaluating marketing strategies. If a large percentage of customers for a product belongs to groups that have not previously been targeted, marketers may reconsider their targets—and their allocation of marketing spending.

4.2Growth: Percentage and CAGR

There are two common measures of growth. Year-on-year percentage growth uses the prior year as a base for expressing percentage change from one year to the next. Over longer periods of time, Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) is a generally accepted metric for average growth rates.

Same Stores Growth is a metric that calculates growth only on the basis of stores that were fully established in both the prior and current periods.

Purpose: To measure growth.

Growth is the aim of virtually all businesses. Indeed, perceptions of the success or failure of many enterprises are based on assessments of their growth. Measures of year-on-year growth, however, are complicated by two factors:

Changes over time in the base from which growth is measured: Such changes might include increases in the number of stores, markets, or salespeople generating sales. This issue is addressed by using “same store” measures (or corollary measures for markets, sales personnel, and so on).

Compounding of growth over multiple periods: For example, if a company achieves 30% growth in one year, but its results remain unchanged over the two subsequent years, this would not be the same as 10% growth in each of three years. CAGR is a metric that addresses this issue.

Construction

Percentage growth is the central plank of year-on-year analysis. It addresses the question: What has the company achieved this year, compared to last year? Dividing the results for the current period by the results for the prior period will yield a comparative figure. Subtracting one from the other will highlight the increase or decrease between periods. When evaluating comparatives, one might say that results in Year 2 were, for example, 110% of those in Year 1. To convert this figure to a growth rate, one need only subtract 100%.

The periods considered are often years, but any time frame can be chosen.

Example: Ed’s is a small deli that has had great success in its second year of operation. Revenues in Year 2 are $570,000, compared with $380,000 in Year 1. Ed calculates his second-year sales results to be 150% of first-year revenues, indicating a growth rate of 50%.

Same Stores Growth: This metric is at the heart of retail analysis. It enables marketers to analyze results from stores that have been in operation for the entire period under consideration. The logic is to eliminate the stores that have not been open for the full period to ensure comparability. Thus, this metric sheds light on the effectiveness with which equivalent resources were used in the period under study versus the prior period. In retail, modest same stores growth and high general growth rates would indicate a rapidly expanding organization, in which growth is driven by investment. When both same stores growth and general growth are strong, a company can be viewed as effectively using its existing base of stores.

Example: A small retail chain in Bavaria posts impressive percentage growth figures, moving from €58 million to €107 million in sales (84% growth) from one year to the next. Despite this dynamic growth, however, analysts cast doubt on the firm’s business model, warning that its Same Stores Growth measure suggests that its concept is failing (see Table 4.4).

Table 4.4 Revenue of a Bavarian Chain Store

Store |

Opened |

Revenue First Year (millions) |

Revenue Second Year (millions) |

A |

Year 1 |

€10 |

€9 |

B |

Year 1 |

€19 |

€20 |

C |

Year 1 |

€20 |

€15 |

D |

Year 1 |

€9 |

€11 |

E |

Year 2 |

n/a |

€52 |

|

|

€58 |

€107 |

Same Stores Growth excludes stores that were not open at the beginning of the first year under consideration. For simplicity, we assume that stores in this example were opened on the first day of Years 1 and 2, as appropriate. On this basis, same stores revenue in Year 2 would be €55 million—that is, the €107 million total for the year less the €52 million generated by the newly opened Store E. This adjusted figure can be entered into the Same Stores Growth formula:

As demonstrated by its negative Same Stores Growth figure, sales growth at this firm has been fueled entirely by a major investment in a new store. This raises serious doubts about its existing store concept. It also leads to a question: Did the new store “cannibalize” existing store sales? (See the next section for cannibalization metrics.)

Compounding Growth, Value at Future Period: By compounding, managers adjust growth figures to account for the iterative effect of improvement. For example, 10% growth in each of two successive years would not be the same as a total of 20% growth over the two-year period. The reason: Growth in the second year is built upon the elevated base achieved in the first. Thus, if sales run $100,000 in Year 0 and rise by 10% in Year 1, then Year 1 sales come to $110,000. If sales rise by a further 10% in Year 2, however, then Year 2 sales do not total $120,000. Rather, they total $110,000 + (10% * $110,000) = $121,000.

The compounding effect can be easily modeled in spreadsheet packages, which enable you to work through the compounding calculations one year at a time. To calculate a value in Year 1, multiply the corresponding Year 0 value by one plus the growth rate. Then use the value in Year 1 as a new base and multiply it by one plus the growth rate to determine the corresponding value for Year 2. Repeat this process through the required number of years.

Example: Over a three-year period, $100, compounded at a 10% growth rate, yields $133.10.

Year 0 to Year 1 $100 + 10% Growth (that is, $10) = $110

Year 1 to Year 2 $110 + 10% Growth (that is, $11) = $121

Year 2 to Year 3 $121 + 10% Growth (that is, $12.10) = $133.10

There is a mathematical formula that generates this effect. It multiplies the value at the beginning—that is, in Year 0—by one plus the growth rate to the power of the number of years over which that growth rate applies.

Example: Using the formula, we can calculate the impact of 10% annual growth over a period of three years. The value in Year 0 is $100. The number of years is 3. The growth rate is 10%.

Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR): A constant year-on-year growth rate applied over a period of time. Given starting and ending values and the length of the period involved, it can be calculated as follows:

CAGR (%) = {[Ending Value ($, #)/Starting Value ($, #)] ^ 1/Number of Periods (#)} − 1

Example: Let’s assume we have the results of the compounding growth observed in the previous example, but we don’t know what the growth rate was. We know that the starting value was $100, the ending value was $133.10, and the number of years was 3. We can simply enter these numbers into the CAGR formula to derive the CAGR.

Thus, we determine that the growth rate was 10%.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Percentage growth is a useful measure as part of a package of metrics. It can be deceiving, however, if not adjusted for the addition of such factors as stores, salespeople, or products or for expansion into new markets. “Same store” sales and similar adjustments for other factors tell us how effectively a company uses comparable resources. These adjustments, however, are limited by their deliberate omission of factors that weren’t in operation for the full period under study. Adjusted figures must be reviewed in tandem with measures of total growth.

Be careful about the difference between percentage changes and changes in percentage points. Consider a firm that grew 10% last year. This year, a marketer might say that the rate of growth increased by 10%. This means that the growth was 10% more than last year, so 10% * (1 + 10%) means growth was 11%. If growth increased by 10 percentage points, growth would now be 20%. It had increased from 10% and added 10 more percentage points. This is dramatically different.

You may also hear about basis points, a related term. Basis points are simply percentage points divided by 100, so 50 basis points equal 0.5%. Basis points are often used in finance because fractional percentage point differences can make very significant differences in outcomes, and it is easier to speak of basis points than fractions of a percentage point.

Related Metrics and Concepts

Life Cycle: Marketers view products as passing through four stages of development:

Introductory: Small markets not yet growing fast

Growth: Larger markets with faster growth rates

Mature: Largest markets but little or no growth

Decline: Variable size markets with negative growth rates

This is a rough classification. No generally accepted rules exist for making these classifications.

4.3Cannibalization Rates and Fair Share Draw

Cannibalization is the reduction in sales (units or dollars) of a firm’s existing products due to the introduction of a new product. The cannibalization rate is generally calculated as the percentage of a new product’s sales that represents a loss of sales (attributable to the introduction of the new entrant) of a specific existing product or products.

Cannibalization rates represent an important factor in the assessment of new product strategies.

Fair share draw constitutes an assumption or expectation that a new product will capture sales (in unit or dollar terms) from existing products in proportion to the market shares of those existing products.

Cannibalization is a familiar business dynamic. A company with a successful product that has strong market share faces two conflicting ideas. The first is that it wants to maximize profits on its existing product line, concentrating on the current strengths that promise success in the short term. The second idea is that this company—or its competitors—may identify opportunities for new products that better fit the needs of certain segments. If the company introduces a new product in this field, however, it may “cannibalize” the sales of its existing products. That is, it may weaken the sales of its proven, already successful product line. If the company declines to introduce the new product, however, it leaves itself vulnerable to competitors launching such a product and thereby capturing sales and market share from the company. Often, when new segments are emerging and there are advantages to being early to market, the key factor becomes timing. If a company launches its new product too early, it may lose too much income on its existing line; if it launches too late, it may miss the new opportunity altogether.

Cannibalization: A market phenomenon in which sales of one product are achieved at the expense of some of a firm’s other products.

The cannibalization rate is the percentage of sales of a new product that comes from a specific set of existing products.

Example: A company has a single product that sold 10 units in the previous period. The company plans to introduce a new product that will sell 5 units with a cannibalization rate of 40%. Thus, 40% of the sales of the new product (40% * 5 units = 2 units) comes at the expense of the old product. Therefore, after cannibalization, the company can expect to sell 8 units of the old product and 5 of the new product, or 13 units in total.

Any company considering introducing a new product should confront the potential for cannibalization. A firm would do well to ensure that the amount of cannibalization is estimated beforehand to provide an idea of how the product line’s contribution as a whole will change. If performed properly, this analysis will tell a company whether overall profits can be expected to increase or decrease with the introduction of the new product line.

Example: Lois sells umbrellas on a small beach, where she is the only provider. Her financials for last month were as follows:

Umbrella Sales Price: |

$20 |

Variable Cost per Umbrella: |

$10 |

Umbrella Contribution per Unit: |

$10 |

Total Unit Sales per Month: |

100 |

Total Monthly Contribution: |

$1,000 |

Next month, Lois plans to introduce a bigger, lighter-weight umbrella called the “Big Block.” Projected financials for the Big Block are as follows:

Big Block Sales Price: |

$30 |

Variable Cost per Big Block: |

$15 |

Big Block Contribution per Unit: |

$15 |

Total Unit Sales per Month (Big Block): |

50 |

Total Monthly Contribution (Big Block): |

$750 |

If there is no cannibalization, Lois thus expects her total monthly contribution will be $1,000 + $750 = $1,750. Upon reflection, however, Lois thinks that the unit cannibalization rate for Big Block will be 60%. Her projected financials after accounting for cannibalization are therefore as follows:

Big Block Unit Sales: |

50 |

Cannibalization Rate: |

60% |

Regular Umbrella Sales Lost: |

50 * 60% = 30 |

New Regular Umbrella Sales: |

100 − 30 = 70 |

New Total Contribution (Regular): |

70 Units * $10 Contribution per Unit = $700 |

Big Block Total Contribution: |

50 Units * $15 Contribution per Unit = $750 |

Lois’s Total Monthly Contribution: |

$1,450 |

Under these projections, total umbrella sales will increase from 100 to 120, and total contribution will increase from $1,000 to $1,450. Lois will replace 30 regular sales with 30 Big Block sales and gain an extra $5 unit contribution on each. She will also sell 20 more umbrellas than she sold last month and gain $15 unit contribution on each.

In this scenario, Lois is in the enviable position of being able to cannibalize a lower-margin product with a higher-margin one. Sometimes, however, new products carry unit contributions lower than those of existing products. In such instances, cannibalization reduces overall profits for the firm.

An alternative way to account for cannibalization is to use a weighted contribution margin. In the previous example, the weighted contribution margin would be the unit margin Lois receives for Big Block after accounting for cannibalization. Because each Big Block contributes $15 directly and cannibalizes the $10 contribution generated by regular umbrellas at a 60% rate, Big Block’s weighted contribution margin is $15 − (0.6 * $10), or $9 per unit. Because Lois expects to sell 50 Big Blocks, her total contribution is projected to increase by 50 * $9, or $450. This is consistent with our previous calculations.

If the introduction of Big Block requires some fixed marketing expenditure, then the $9 weighted margin can be used to find the break-even number of Big Block sales required to justify that expenditure. For example, if the launch of Big Block requires $360 in one-time marketing costs, then Lois needs to sell $360/$9, or 40 Big Blocks to break even on that expenditure.

If a new product has a margin lower than that of the existing product that it cannibalizes, and if its cannibalization rate is high enough, then its weighted contribution margin might be negative. In that case, company earnings will decrease with each unit of the new product sold.

Cannibalization refers to a dynamic in which one product of a firm takes share from one or more other products of the same firm. When a product takes sales from a competitor’s product, that is not cannibalization, although managers sometimes incorrectly state that their new products are “cannibalizing” sales of a competitor’s goods. You can only cannibalize your own sales; taking sales from rivals is not considered cannibalization.

Though it is not cannibalization, the impact of a new product on the sales of competing goods is an important consideration in a product launch. One simple assumption about how the introduction of a new product might affect the sales of existing products is called fair share draw.

Fair Share Draw: The assumption that a new product will capture sales (in unit or dollar terms) from existing products in direct proportion to the market shares held by those existing products.

Example: Three rivals compete in the youth fashion market in a small town. Their sales and market shares for last year appear in the following table:

Firm |

Sales |

Share |

Threadbare |

$500,000 |

50% |

Too Cool for School |

$300,000 |

30% |

Tommy Hitchhiker |

$200,000 |

20% |

Total |

$1,000,000 |

100% |

A new entrant is expected to enter the market in the coming year and to generate $300,000 in sales. Two-thirds of those sales are expected to come at the expense of the three established competitors. Under an assumption of fair share draw, how much will each firm sell next year?

If the new firm takes two-thirds of its sales from existing competitors, then this “capture” of sales will total (2/3) * $300,000, or $200,000. Under fair share draw, the breakdown of that $200,000 will be proportional to the shares of the current competitors. Thus, 50% of the $200,000 will come from Threadbare, 30% from Too Cool, and 20% from Tommy. The following table shows the projected sales and market shares next year of the four competitors under the fair share draw assumption:

Firm |

Sales |

Share |

Threadbare |

$400,000 |

36.36% |

Too Cool for School |

$240,000 |

21.82% |

Tommy Hitchhiker |

$160,000 |

14.55% |

New Entrant |

$300,000 |

27.27% |

Total |

$1,100,000 |

100% |

Notice that the new entrant expands the market by $100,000, an amount equal to the sales of the new entrant that do not come at the expense of existing competitors. Notice also that under fair share draw, the relative shares of the existing competitors remain unchanged. For example, Threadbare’s share, relative to the total of the original three competitors, is 36.36/(36.36 + 21.82 + 14.55), or 50%—equal to its share before the entry of the new competitor.

The opposite of cannibalization is incremental sales. This is when the introduction of a new product may boost sales for a complementary product—one that naturally goes with the product.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

As noted previously, with cannibalization, one of a firm’s products takes sales from one or more of that firm’s other products. Sales taken from the products of competitors are not “cannibalized” sales, although some managers label them as such.

Cannibalization rates depend on how the features, pricing, promotion, and distribution of the new product compare to those of a firm’s existing products. The greater the similarity of their respective marketing strategies, the higher the cannibalization rate is likely to be.

Although cannibalization is always an issue when a firm launches a new product that competes with its established line, this dynamic is particularly damaging to the firm’s profitability when a low-margin entrant captures sales from the firm’s higher-margin offerings. In such cases, the new product’s weighted contribution margin can be negative. Even when cannibalization rates are significant, however, and even if the net effect on the bottom line is negative, it may be wise for a firm to proceed with a new product if management believes that the original line is losing its competitive strength. The following example is illustrative.

Example: A producer of powdered-milk formula has an opportunity to introduce a new, improved formula. The new formula has certain attributes not found in the firm’s existing products. Due to higher costs, however, it will carry a contribution margin of only $8, compared with the $10 margin of the established formula. Analysis suggests that the unit cannibalization rate of the new formula will be 90% in its initial year. If the firm expects to sell 300 units of the new formula in its first year, should it proceed with the introduction?

Analysis shows that the new formula will generate $8 * 300, or $2,400 in direct contribution. Cannibalization, however, will reduce contribution from the established line by $10 * 0.9 * 300, or $2,700. Thus, the company’s overall contribution will decline by $300 with the introduction of the new formula. (Note also that the weighted unit margin for the new product is –$1.) This simple analysis suggests that the new formula should not be introduced.

The following table, however, contains the results of a more detailed four-year analysis. Reflected in this table are management’s beliefs that without the new formula, sales of the regular formula will decline to 700 units in Year 4. In addition, unit sales of the new formula are expected to increase to 600 in Year 4, while cannibalization rates decline to 60%.

|

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Total |

Unit Sales of Regular Formula Without New Product Launch |

1,000 |

900 |

800 |

700 |

3,400 |

|

|

— |

|

— |

|

Unit Sales of New Formula |

300 |

400 |

500 |

600 |

1,800 |

Cannibalization Rate |

90% |

80% |

70% |

60% |

— |

Unit Sales of Regular Formula with New Product Launch |

730 |

580 |

450 |

340 |

2,100 |

Without the new formula, total four-year contribution is projected as $10 * 3,400 = $34,000. With the new formula, total contribution is projected as ($8 * 1,800) + ($10 * 2,100) = $35,400. Although forecast contribution is lower in Year 1 with the new formula than without it, total four-year contribution is projected to be higher with the new product due to increases in new-formula sales and decreases in the cannibalization rate.

4.4Brand Equity Metrics

Brand equity is strategically crucial but famously difficult to quantify. Many experts have developed tools to analyze this asset, but there’s no universally accepted way to measure it. In this section, we consider the following techniques to gain insight in this area:

Brand Equity Ten (Aaker)

BrandAsset® Valuator (BAV Group/VSLY&R)

Brand Finance

BrandZ (Millward Brown)

Brand Valuation Model (Interbrand)

Purpose: To measure the value of a brand.

A brand encompasses the name, logo, image, and perceptions that identify a product, service, or provider in the minds of customers. It takes shape in advertising, packaging, and other marketing communications and becomes a focus of the relationship with consumers. In time, a brand comes to embody a promise about the goods it identifies—a promise about quality, performance, or other dimensions of value that can influence consumers’ choices among competing products. When consumers trust a brand and find it relevant, they may select the offerings associated with that brand over those of competitors, even at a premium price. Often people refer to brand equity as the incremental unit sales and/or price a product commands. Be careful not to confuse a brand’s equity with only the premium price that it can command in a market. It should be noted that a complete measure of brand equity should also include the additional volume that is generated because of the product’s name. Some firms elect to capture most of this value in price, such as for luxury goods, and sometimes in volume, such as for discounters. Most of the time, it is some of both.

When a brand’s promise extends beyond a particular product, its owner may leverage it to enter new markets. This is another component of the brand’s equity. As when measuring brand equity in its traditional market, the brand’s equity in the new market is the incremental volume and/or price the product is able to attain in this new market attributable to the brand itself. As such, a brand can hold tremendous value.

Brand equity can be remarkably difficult to measure. At a corporate level, when one company buys another, analysts might apportion some of the excess of the purchase price over the value of recorded assets purchased to shed light on the value of the brands acquired. Beyond the value of its assets on the firm’s balance sheet, a company’s brands typically constitute important, unrecorded, intangible assets. Of course, a company’s brands are rarely the only unrecorded items acquired in such a transaction. The excess of purchase price over recorded value frequently encompasses intellectual property, distribution systems, customer lists, and other intangibles in addition to brand. Firm valuations (sales or share prices) are also subject to economic cycles, investor “exuberance,” and other influences that are difficult to separate from the intrinsic value. One often wants to consider the discounted cash flow from the incremental volume and price into current dollars. This requires forecasting sales and the influence of the brand into the future, which adds another degree of complexity to this measure.

From a consumer’s perspective, the value of a brand might be the amount she would be willing to pay for merchandise that carries the brand’s name, over and above the price she’d pay for identical unbranded goods.2 Marketers strive to estimate this premium in order to gain insight into brand equity. Here again, however, they encounter daunting complexities, as individuals vary not only in their awareness of different brands but in the criteria by which they judge them, the evaluations they make, and the degree to which those opinions guide their purchase behavior. In a similar vein, the value of the brand might be the increased propensity to buy the product because it carries the brand name. This heterogeneity across the population reflects that the brand’s value to one individual might be very different from another’s. For example, the Starbucks brand might be very appealing to an individual, and it might make the person more likely to buy coffee at a Starbucks and willing to pay extra for it because it is Starbucks coffee. For another individual who may not like the taste of Starbucks coffee or the atmosphere of Starbucks shops, the value of the Starbucks brand might be zero and perhaps even negative.

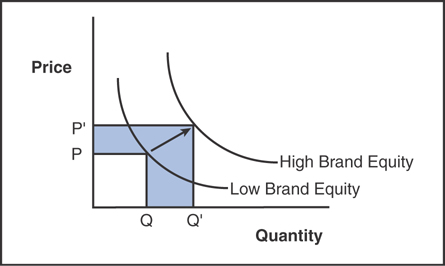

Theoretically, a marketer might aggregate these preferences across an entire population to estimate the total premium its members would pay for goods of a certain brand. Even that, however, wouldn’t fully capture brand equity. Kusum Ailawadi and her colleagues contend that the equity of a brand is better captured by its overall revenue premium (relative to generic goods) than by its price per unit alone. The revenue figure incorporates both price and quantity and so reflects a jump from one demand curve to another rather than a movement along a single curve.3

A successful brand shifts the demand curve for its goods or services outward; that is, it not only enables a provider to charge a higher price (P' rather than P, as shown in Figure 4.3), but it also sells an increased quantity (Q' rather than Q). Thus, brand equity in this example can be viewed as the difference between the revenue with the brand (P' * Q') and the revenue without the brand (P * Q)—depicted as the shaded area in Figure 4.3. (Of course, this example focuses on revenue, when, in fact, it is profit or present value of profits that matters more. But, given that the increase in price associated with the brand comes with no incremental variable costs, this lift represents profits as well.)

Figure 4.3 Brand Equity: Outward Shift of Demand Curve

A graph illustrating an outward shift of the demand curve. The horizontal axis represents the quantity and the vertical axis represents the price. Two curves, low brand equity at (Q, P) and high brand equity at (Q prime, P prime). There is a shift in demand from low brand equity to high brand equity, resulting in an increase in price from P to P prime and an increase in quantity from Q to Q prime.

In practice, of course, it’s difficult to measure a demand curve, and few marketers do so. Because brands are crucial assets, however, both marketers and academic researchers have devised means to contemplate their value. David Aaker, for example, tracks ten attributes of a brand to assess its strength, VSLY&R, a marketing consultancy, has developed a tool called the BrandAsset® Valuator, which measures a brand’s power on the basis of differentiation, relevance, esteem, and knowledge. An even more theoretical conceptualization of brand equity is the difference of the firm value with and without the brand. If you find it difficult to imagine a firm without its brand, then you can appreciate how difficult it is to quantify brand equity. Interbrand, a brand strategy agency, draws upon its own model to separate tangible product value from intangible brand value and uses the latter to rank the top 100 global brands each year. Finally, conjoint analysis can shed light on a brand’s value because it enables marketers to measure the impact of that brand on customer preference, treating it as one among many attributes that consumers trade off in making purchase decisions (see Section 4.5).

Construction

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has standards for brand valuation (10668) and brand evaluation (20671). (Valuation is usually used to refer to supplying dollar values, whereas evaluation is a wider term related to general brand health.) MASB sees ISO 20671, which was adopted in 2018, as a crucial step in helping accountable marketers build and manage their brands. A key requirement of the recent ISO standard is that there be a regular brand evaluation. Marketers should actively manage and monitor brands, which are a key asset for many firms.

Brand Equity Ten (Aaker) David Aaker, a marketing professor and brand consultant, highlights ten attributes of a brand that can be used to assess its strength: differentiation, satisfaction or loyalty, perceived quality, leadership or popularity, perceived value, brand personality, organizational associations, brand awareness, market share, and market price and distribution coverage. Aaker doesn’t weight the attributes or combine them in an overall score, as he believes any weighting would be arbitrary and would vary among brands and categories. Rather, he recommends tracking each attribute separately.

Brandasset Valuator (BAV Group/VSLY&R)

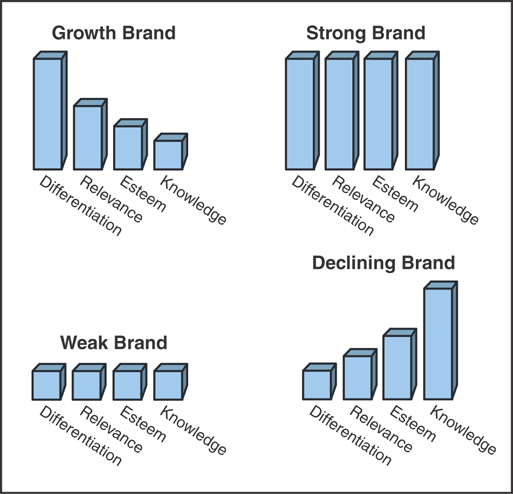

BrandAsset® Valuator is a tool for diagnosing the power and value of a brand by surveying consumers’ perspectives along four dimensions:

Differentiation: The defining characteristics of the brand and its distinctiveness relative to competitors

Relevance: The appropriateness and connection of the brand to a given consumer

Esteem: Consumers’ respect for and attraction to the brand

Knowledge: Consumers’ awareness of the brand and understanding of what it represents

BAV Group/VSLY&R maintains that these criteria reveal important factors behind brand strength and market dynamics. For example, although powerful brands score high on all four dimensions, growing brands may earn higher grades for differentiation and relevance than for knowledge and esteem. Fading brands often show the reverse pattern, as they’re widely known and respected but may be declining toward commoditization or irrelevance (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 BAV Group/VSLY&R BrandAsset® Valuator Patterns of Brand Equity

A figure reveals the patterns of four brand assets belonging to BAV group/ VSLY and R. The brands are classified as growth brand, strong brand, weak brand, and declining brand. The dimension of these brands is differentiation, relevance, esteem, and knowledge. The growth brands obtain a higher rank for differentiation and relevance and lower rank for esteem and knowledge. The strong brands maintain higher standards for four dimensions. The weak brand scores lower grades for four dimensions. The declining brands show a reverse pattern of growth brand. That is knowledge and esteem achieve the higher grades whereas differentiation scores a lower grade.

The BrandAsset® Valuator is a proprietary tool, but the concepts behind it have broad appeal. Many marketers apply these concepts by conducting independent research and exercising judgment about their own brands relative to the competition. Leon Ramsellar of Philips Consumer Electronics, for example, has reported using four key measures in evaluating brand equity and offers sample questions for assessing them:4

Uniqueness: Does this product offer something new to me?

Relevance: Is this product relevant for me?

Attractiveness: Do I want this product?

Credibility: Do I believe in the product?

Clearly, Ramsellar’s list is not the same as the BrandAsset® Valuator, but the similarity of the first two factors is hard to miss.

Brand Finance

Founded in 1996, Brand Finance is an independent intangible asset valuation consultancy based in the UK with offices in more than 20 countries. It focuses on valuation of a firm’s intangible assets.

The Brand Finance methodology specifies three alternative brand valuation approaches: the market, cost, and income approaches.

The basis for its calculation is centered around a concept of “Royalty Relief”—that is, how much a company would have to pay for the use of the brand name if it belonged to someone else.

Royalty Relief methodology: Brand Finance uses a Royalty Relief methodology when calculating the value of a brand. This approach is based on the assumption that if the company did not own the trademarks that it benefits from, it would need to license them from a third-party brand owner and pay a licensing fee. Ownership of the trademarks relieves the company from paying this royalty fee.

Royalty Relief valuation formula: The Royalty Relief method involves estimating likely future sales, applying an appropriate royalty rate to them, and then discounting estimated future, post-tax royalties to arrive at a net present value, which is held to represent the brand value.

Brand ratings: In determining the appropriate royalty rate, Brand Finance establishes a range of comparable royalty rates and determines the point within the range where the brand under review falls by reference to a brand rating. The brand rating is calculated using Brand Finance’s BrandBeta analysis, which benchmarks the strength, risk, and potential of a brand, relative to its competitors, on a scale ranging from AAA to D. It is conceptually similar to a credit rating. The data used to calculate the ratings come from various sources, including Bloomberg, annual reports, client-commissioned research, and Brand Finance internal research.

Brandz (Millward Brown)

BrandZ, which is Millward Brown’s brand equity database, holds data from more than 2 million consumers and professionals across 50 markets and compares more than 165,000 brands (www.brandz.com/about-us). The database is used to estimate brand valuations, and each year since 2006, it has been used to generate a list of the top 100 global brands.

The objective of the BrandZ methodology is to peel away all financial components of brand value to determine how much brand alone contributes to brand value. BrandZ conducts worldwide, ongoing, in-depth quantitative consumer research and builds up a global picture of brands on category-by-category and country-by-country bases. BrandZ uses the following pillars to anchor its brand valuation:

Meaningful: In any category, meaningful brands appeal more, generate greater “love,” and meet the individual’s expectations and needs.

Different: Different brands are unique in a positive way and “set the trends,” staying ahead of the curve for the benefit of the consumer.

Salient: Salient brands come spontaneously to mind as brands of choice for key needs.

BrandZ uses the following valuation process:

Calculate financial value:

Part A

Determine total corporate earnings from the corporation’s entire portfolio of brands.

Analyze financial information from annual reports and other sources, such as Kantar Worldpanel and Kantar Retail. This analysis yields a metric called Attribution Rate.

Multiply Corporate Earnings by Attribution Rate to arrive at Branded Earnings, the amount of Corporate Earnings attributed to a particular brand. If the Attribution Rate of a brand is 50%, for example, then half the Corporate Earnings are identified as coming from that brand.

Part B

Determine future earnings and attribute an earnings multiple to the company. Information supplied by Bloomberg data is used to calculate the Brand Multiple. BrandZ multiplies Branded Earnings by Brand Multiple to arrive at Financial Value.

Calculate brand contribution:

To arrive at Brand Value, peel away a few more layers, such as other factors that influence the value of the branded business (for example, price, convenience, availability, and distribution).

Because a brand exists in the mind of the consumer, assess the brand’s uniqueness and its ability to stand out from the crowd, generate desire, and cultivate loyalty. This unique role played by brand is called Brand Contribution.

Calculate brand value:

Multiply Financial Value by Brand Contribution, which is expressed as a percentage of Financial Value. The result is Brand Value. Brand Value is the dollar amount a brand contributes to the overall value of a corporation. Isolating and measuring this intangible asset reveals an additional source of shareholder value that otherwise would not exist.

Brand Valuation Model (Interbrand)

Interbrand, a division of Omnicom, is a brand consultancy headquartered in New York City (see www.interbrand.com).

Interbrand publishes the Best Global Brands report on an annual basis. The report identifies the world’s 100 most valuable brands. To develop the report, Interbrand examines three key aspects that contribute to a brand’s value:

The financial performance of the branded products or service

The role the brand plays in influencing consumer choice

The strength the brand has to command a premium price or secure earnings for the company

Interbrand has refined its brand valuation into a five-step Economic Value Added methodology. Through a similar methodology, Interbrand releases an annual ranking of the best global brands in its Best Global Brands report, which evaluates each brand’s financial performance, role, and strength. To qualify, brands must have a presence on at least three major continents and must have broad geographic coverage in growing and emerging markets. Thirty percent of revenues must come from outside the home country, and no more than 50% of revenues should come from any one continent. Economic profit must be expected to be positive over the longer term, delivering a return above the brand’s cost of capital. The brand must have a public profile and awareness across the major economies of the world.

The brand valuation methodology involves three key metrics:

Financial Analysis: This metric measures the overall financial return to an organization’s investors, or its “economic profit.” Economic profit is the after-tax operating profit of the brand minus a charge for the capital used to generate the brand’s revenue and margins.

Role of Brand: Role of Brand measures the portion of the purchase decision attributable to the brand, as opposed to other factors (for example, purchase drivers like price, convenience, or product features). Role of Brand Index (RBI) quantifies this as a percentage. RBI determinations for Best Global Brands derive, depending on the brand, from one of three methods: primary research, a review of historical roles of brands for companies in that industry, or expert panel assessment.

Brand Strength: Brand Strength measures the ability of the brand to create loyalty and, therefore, sustainable demand and profit into the future. Brand Strength analysis is based on an evaluation across several factors that Interbrand believes make a strong brand; factors are weighted and add up to 100. These factors include leadership (25), stability (15), market (10), geographic spread (25), trend (10), support (10), and protection (5). Performance on these factors is judged relative to other brands in the industry and relative to other world-class brands. The Brand Strength analysis delivers a snapshot of the strengths and weaknesses of the brand and is used to generate a road map of activity to enhance the strength and value of the brand in the future.

Conjoint Analysis

Marketers use conjoint analysis to measure consumers’ preference for various attributes of a product, service, or provider, such as features, design, price, or location (see Section 4.5). By including brand and price as two of the attributes under consideration, they can gain insight into consumers’ valuation of a brand—that is, their willingness to pay a premium for it.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

The methods described previously represent experts’ best attempts to place a value on a complex and intangible entity. Almost all of the metrics in this book are relevant to brand equity along one dimension or another.

Related Metrics and Concepts

Brand strategy is a broad field and includes several concepts that at first may appear to be measurable. Strictly speaking, however, brand strategy is not a metric.

Brand Identity: This is the marketer’s vision of an ideal brand—the company’s goal for perception of that brand by its target market. All physical, emotional, visual, and verbal messages should be directed toward realization of that goal, including name, logo, signature, and other marketing communications. Brand Identity, however, is not stated in quantifiable terms.

Brand Position and Brand Image: These metrics refer to consumers’ actual perceptions of a brand, often relative to its competition. Brand Position is frequently measured along product dimensions that can be mapped in multidimensional space. If measured consistently over time, these dimensions may be viewed as metrics—as coordinates on a perceptual map. (See Section 2.7 for a discussion of attitude, usage measures, and the hierarchy of effects.)

Product Differentiation: This is one of the most frequently used terms in marketing, but it has no universally agreed-upon definition. More than mere “difference,” it generally refers to distinctive attributes of a product that generate increased customer preference or demand. These are often difficult to view quantitatively because they may be actual or perceived—as well as non-monotonic. In other words, although certain attributes such as price can be quantified and may follow a linear preference model (that is, either more or less is always better), others can’t be analyzed numerically or may fall into a sweet spot, outside of which neither more nor less would be preferred (the spiciness of a food, for example). For all these reasons, Product Differentiation is hard to analyze as a metric and has been criticized as a “meaningless term.”5

4.5Conjoint Utilities and Consumer Preference

Conjoint analysis is a form of data collection and analysis that measures relative customer preferences for a level of an attribute. Conjoint analysis has had several different names over the years. Trade-off analysis and choice modeling are extensions of the original conjoint methodology. We refer to “conjoint” to describe this entire class of analysis.

Conjoint utilities or weights measure consumer preference for an attribute level and then—by combining the valuations of multiple attributes—measure preference for an overall choice. Measures are generally made on an individual basis, although this analysis can also be performed at the segment level. In recent years, another variant of Bayesian choice modeling or Bayesian discrete choice modeling has been used to similarly measure the relative attribute-level weights leading to option or brand choice. In the frozen pizza market, for example, conjoint utilities can be used to determine how much a customer values superior taste (one attribute) versus paying extra for premium cheese (a second attribute).

Conjoint utilities can also play a role in analyzing compensatory decisions—that is, where weaknesses in some attributes can be made up, or compensated for, in other attributes. A weakness in a non-compensatory factor cannot be overcome by other strengths.

Conjoint analysis can be useful in determining what customers want and—when price is included as an attribute—is sometimes used for what they’ll pay for it. In launching new products, marketers find such analyses useful for achieving a deeper understanding of the values that customers place on various product attributes. Throughout product management, conjoint utilities can help marketers focus their efforts on the attributes of greatest importance to customers.

Purpose: To understand the relative preferences of consumers for product attributes.

Conjoint analysis is a method used to estimate customers’ preferences, based on how customers weight the attributes on which a choice is made. The premise of conjoint analysis is that a customer’s preference between product options can be broken into a set of attributes that are weighted to form an overall evaluation. Rather than ask people directly what they want and why, in conjoint analysis, marketers ask people about their overall preferences for a set of choices described on their attributes and then decompose those into the component dimensions and weights underlying them. A model can be developed to compare sets of attributes to determine which represents the most appealing bundle of attributes for customers.

Conjoint analysis is a technique commonly used to assess the attributes of a product or service that are important to targeted customers and to assist in the following:

Product design

Advertising copy

Pricing

Segmentation

Forecasting

Construction

Conjoint Analysis/Choice Modeling: A method of estimating customers’ preference by assessing the overall preferences or choices customers assign to alternative options.

An individual’s preference or choice can be expressed as the total of his or her baseline preferences for any option, plus the partworths (relative values) for that choice expressed by the individual.

In a linear form, this can be represented by the following formula:

Example: Two attributes of a smartphone, its price and its size, are ranked through conjoint analysis, yielding the results shown in Table 4.5.

Table 4.5 Conjoint Analysis: Price and Size of a Smartphone

Attribute |

Level |

Partworth |

Price |

$500 |

0.9 |

Price |

$600 |

0.1 |

Price |

$700 |

–1 |

Size |

Small |

0.7 |

Size |

Medium |

–0.1 |

Size |

Large |

–0.6 |

A small smartphone for $500 has a partworth to customers of 1.6 (derived as 0.9 + 0.7). This is the highest result observed in this exercise. A small but expensive ($700) phone is rated as –0.3 (that is, –1 + 0.7). The desirability of this small smartphone is offset by its price. A large, expensive smartphone is least desirable to customers, generating a partworth of –1.6 (that is, –1 + –0.6).

On this basis, we determine that the customer whose views are analyzed here would prefer a medium-size phone at $600 (utility = 0) to a small phone at $700 (utility = –0.3). Such information would be informative to decisions concerning the trade-offs between product design and price.

This analysis also demonstrates that, within the ranges examined, price is more important than size from the perspective of this consumer. Price generates a range of effects from 0.9 to –1 (that is, a total spread of 1.9), while the effects generated by the most and least desirable sizes span a range only from 0.7 to –0.6 (total spread = 1.3).

Ideally, if the partworths are measured correctly, by assessing the partworth of a feature relative to the corresponding partworth for price, it would be possible to measure a willingness to pay (WTP) for a feature or level of a feature.6

Compensatory Versus Non-compensatory Consumer Decisions

A compensatory decision process is one in which a customer evaluates choices with the perspective that strengths along one or more dimensions can compensate for weaknesses along others.

In a non-compensatory decision process, by contrast, if certain attributes of a product are weak, no compensation is possible, even if the product possesses strengths along other dimensions. In the previous smartphone example, for instance, some customers may feel that if a phone were greater than a certain size, no price would make it attractive.

In another example, most people choose a grocery store on the basis of proximity. Any store within a certain radius of home or work may be considered. Beyond that distance, however, all stores will be excluded from consideration, and there is nothing a store can do to overcome this. Even if it posts extraordinarily low prices, offers a stunningly wide assortment, creates great displays, and stocks the freshest foods, for example, a store will not entice consumers to travel 400 miles to buy groceries.

Although this example is extreme to the point of absurdity, it illustrates an important point: When consumers make a choice on a non-compensatory basis, marketers need to define the dimensions along which certain attributes must be delivered simply to qualify for consideration of their overall offering.

One form of non-compensatory decision making is elimination by aspect. In this approach, consumers look at an entire set of choices and then eliminate those that do not meet their expectations in the order of the importance of the attributes. In the selection of a grocery store, for example, this process might run as follows:

Which stores are within 5 miles of my home?

Which ones are open after 8 p.m.?

Which carry the spicy mustard that I like?

Which carry fresh flowers?

The process continues until only one choice is left.

In the ideal situation, in analyzing customers’ decision processes, marketers would have access to information on an individual level, revealing

Whether the decision for each customer is compensatory or not

The priority order of the attributes

The “cut-off” levels for each attribute

The relative importance weight of each attribute if the decision follows a compensatory process

More frequently, however, marketers have access only to past behavior in making inferences regarding these items.

In the absence of detailed, individual information for customers throughout a market, conjoint analysis provides a means to gain insight into the decision-making processes of a sampling of customers. In conjoint analysis, we generally assume a compensatory process. That is, we assume utilities are additive. Under this assumption, if a choice is weak along one dimension (for example, if a store does not carry spicy mustard), it can compensate for this with strength along another (for example, it does carry fresh-cut flowers)—at least in part. Conjoint analyses can approximate a non-compensatory model by assigning non-linear weighting to an attribute across certain levels of its value. For example, the weightings for distance to a grocery store might run as follows:

Within 1 mile: |

0.9 |

1–5 miles away: |

0.8 |

5–10 miles away: |

–0.8 |

More than 10 miles away: |

–0.9 |

In this example, stores outside a 5-mile radius cannot practically make up the loss of utility they incur as a result of distance. Distance becomes, in effect, a non-compensatory dimension.

By studying customers’ decision-making processes, marketers gain insight into the attributes needed to meet consumer expectations. They learn, for example, whether certain attributes are compensatory or non-compensatory. A strong understanding of customers’ valuation of different attributes also enables marketers to tailor products and allocate resources effectively.

Several potential complications arise in considering compensatory versus non-compensatory decisions. Customers often don’t know whether an attribute is compensatory or not, and they may not be readily able to explain their decisions. Therefore, it is often necessary either to infer a customer’s decision-making process or to determine that process through an evaluation of choices, rather than a description of the process.

It is possible, however, to uncover non-compensatory elements through conjoint analysis. Any attribute for which the valuation spread is so high that it cannot practically be made up by other features is, in effect, a non-compensatory attribute.

Example: Among grocery stores, Juan prefers the Acme market because it’s close to his home, despite the fact that Acme’s prices are generally higher than those at the local Shoprite store. A third store, Vernon’s, is located in Juan’s apartment complex. But Juan avoids it because Vernon’s doesn’t carry his favorite soda.

From this information, we know that Juan’s shopping choice is influenced by at least three factors: price, distance from his home, and whether a store carries his favorite soda. In Juan’s decision process, price and distance seem to be compensating factors. He trades price for distance. Whether the soda is stocked seems to be a non-compensatory factor. If a store doesn’t carry Juan’s favorite soda, it will not win his business, regardless of how well it scores on price and location.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Prior to conducting a conjoint study, it is necessary to identify the attributes of importance to a customer. Focus groups are commonly used for this purpose. After attributes and levels are determined, a typical approach to conjoint analysis is to use a fractional factorial orthogonal design, which is a partial sample of all possible combinations of attributes. This reduces the total number of choice evaluations required by the respondent. With an orthogonal design, the attributes remain independent of one another, and the test doesn’t weigh one attribute disproportionately to another.

There are multiple ways to gather data, but a straightforward approach would be to present respondents with choices and to ask them to rate those choices according to their preferences. Those preferences then become the dependent variable in a regression, in which attribute levels serve as the independent variables, as in the previous equation. Conjoint utilities constitute the weights determined to best capture the preference ratings provided by the respondent.

Often, certain attributes work in tandem to influence customer choice. For example, a fast and sleek sports car may provide greater value to a customer than would be suggested by the sum of the fast and sleek attributes. Such relationships between attributes are not captured by a simple conjoint model unless one accounts for interactions.

Ideally, conjoint analysis is performed on an individual level because attributes can be weighted differently across individuals. Marketers can also create a more balanced view by performing analysis across a sample of individuals. It is appropriate to perform the analysis within consumer segments that have similar weights. Conjoint analysis can be viewed as a snapshot in time of a customer’s desires. It will not necessarily translate indefinitely into the future.

It is vital to use the correct attributes in any conjoint study. People can only tell you their preferences within the parameters you set. If the correct attributes are not included in a study, while it may be possible to determine the relative importance of those attributes that are included, and it may technically be possible to form segments on the basis of the resulting data, the analytic results may not be valid for forming useful segments. For example, in a conjoint analysis of consumer preferences regarding colors and styles of cars, one may correctly group customers as to their feelings about these attributes. But if consumers really care most about engine size, then those segmentations will be of little value.

4.6Segmentation Using Conjoint Utilities

Understanding customers’ desires is a vital goal of marketing. Segmenting, or clustering similar customers into groups, can help managers recognize useful patterns and identify attractive subsets within a larger market. With that understanding, managers can select target markets, develop appropriate offerings for each, determine the most effective ways to reach the targeted segments, and allocate resources accordingly. Conjoint analysis can be highly useful in this exercise.

Purpose: To identify segments based on conjoint utilities.

As described in the previous section, conjoint analysis is used to determine customers’ preferences on the basis of the attribute weightings that they reveal in their decision-making processes. These weights, or utilities, are generally evaluated on an individual level.

Segmentation entails the grouping of customers who demonstrate similar patterns of preference and weighting with regard to certain product attributes, distinct from the patterns exhibited by other groups. Using segmentation, a company can decide which group(s) to target and can determine an approach to appeal to the segment’s members. After segments have been formed, a company can set strategy based on their attractiveness (size, growth, purchase rate, diversity) and on the company’s capability to serve these segments, relative to competitors.

Construction

To complete a segmentation based on conjoint utilities, one must first determine utility scores at an individual customer level. Next, one must cluster these customers into segments of like-minded individuals. This is generally done through a methodology known as cluster analysis.

Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis is a technique that calculates the distances between customers and forms groups by minimizing the differences within each group and maximizing the differences between groups.

Cluster analysis operates by calculating a “distance” (a sum of squares) between individuals and, in a hierarchical fashion, starts pairing those individuals together. The process of pairing minimizes the “distance” within a group and creates a manageable number of segments within a larger population.

Example: The Samson-Finn Company has three customers. In order to help manage its marketing efforts, Samson-Finn wants to organize like-minded customers into segments. Toward that end, it performs a conjoint analysis in which it measures its customers’ preferences among products that are either reliable or very reliable and either fast or very fast (see Table 4.6). It then considers the conjoint utilities of each of its customers to see which of them demonstrate similar wants. When clustering on conjoint data, the distances are calculated on the partworths.

Table 4.6 Customer Conjoint Utilities

|

Very Reliable |

Reliable |

Very Fast |

Fast |

Bob |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

Erin |

0.9 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.7 |

Yogesh |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

The analysis looks at the difference between Bob’s view and Erin’s view on the importance of reliability on their choice. Bob’s score is 0.4, and Erin’s is 0.9. We can square the difference between these to derive the “distance” between Bob and Erin.

Using this methodology, the distance between each pair of Samson-Finn’s customers can be calculated as follows:

Distances |

Very Reliable |

Reliable |

Very Fast |

Fast |

Bob and Erin: |

= (0.4 − 0.9)2 |

+ (0.3 − 0.1)2 |

+ (0.6 − 0.2)2 |

+ (0.2– 0.7)2 |

|

= 0.25 |

+ 0.04 |

+ 0.16 |

+ 0.25 |

|

= 0.7 |

|

|

|

Bob and Yogesh: |

= (0.4 − 0.3)2 |

+ (0.3 − 0.3)2 |

+ (0.6 − 0.5)2 |

+ (0.2 − 0.2)2 |

|

= 0.01 |

+ 0.0 |

+ 0.01 |

+ 0.0 |

|

= 0.02 |

|

|

|

Erin and Yogesh: |

= (0.9 − 0.3)2 |

+ (0.1 − 0.3)2 |

+ (0.2 − 0.5)2 |

+ (0.7 + 0.2)2 |

|

= 0.36 |

+ 0.04 |

+ 0.09 |

+ 0.25 |

|

= 0.74 |

|

|

|

On this basis, Bob and Yogesh appear to be very close to each other because their sum of squares is 0.02. As a result, they should be considered part of the same segment. Conversely, in light of the high sum-of-squares distance established by her preferences, Erin should not be considered a part of the same segment with either Bob or Yogesh.

Of course, most segmentation analyses are performed on large customer bases. This example merely illustrates the process involved in the cluster analysis calculations.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

As noted previously, a customer’s utilities may not be stable, and the segment to which a customer belongs can shift over time or across occasions. An individual might belong to one segment for personal air travel, in which price might be a major factor, and another for business travel, in which convenience might become more important. Such a customer’s conjoint weights (utilities) would differ depending on the purchase occasion.

Determining the appropriate number of segments for an analysis can be somewhat arbitrary. There is no generally accepted statistical means for determining the “correct” number of segments. Ideally, marketers look for a segment structure that fulfills the following qualifications:

Each segment constitutes a homogeneous group, within which there is relatively little variance between attribute utilities of different individuals.

Groupings are heterogeneous across segments; that is, there is a wide variance of attribute utilities between segments.