11

Online, Email, and Mobile Metrics

Introduction

In this chapter, we focus on metrics used in web-based and other marketing efforts enabled by the widespread use of information technology. Digital marketing has experienced exceptional growth, and the ecosystem remains messy. With respect to metrics, many advertising media terms, such as impressions, are used to describe and evaluate web-based advertising; other terms, such as clickthrough, are unique to the web. Certain web-specific metrics are needed because the internet, like direct mail, serves not only as a communications medium but also as a direct sales channel that can provide real-time feedback on the effectiveness of advertising in generating customer interest and sales. Billboards with 800 numbers or website names and even radio (“tell them JACK sent you”) are also examples of direct-response advertising.

The use of cell phones has an especially significant potential for marketers, as consumers can interact with a firm online around the time of purchase. Offers can also be made to consumers when they are in a location where they can buy, and this is also likely to increase effectiveness. Of course, cell phones also provide much more data on consumer activity, and the privacy implications are still being debated.

With respect to metrics, the internet provides an extremely rich source of data. Indeed, marketers working in this area often have a profusion of data sources, unlike many in traditional areas of marketing. Lots of data are useful only if marketers know what to do with it. This chapter describes some key metrics and their strengths and weaknesses.

|

Metric |

Construction |

Considerations |

Purpose |

11.1 |

Pageviews |

The number of times a web page is served. |

Represents the number of web pages served. |

Provide a top-level measure of the popularity of a website. |

11.2 |

Media Display Time |

The average time that media are displayed per viewer. |

Can be heavily influenced by unusually long display times. How data are gathered is an important consideration. |

Measure average viewing time of media. |

11.2 |

Media Interaction Rate |

The fraction of viewers interacting with the media. |

The definition of interaction should exclude actions unrelated to the media (such as a mouse crossing the media to reach another part of the screen). |

Measure the relative attractiveness of media and the ability to generate viewer engagement. |

11.3 |

Clickthrough Rate |

Number of clickthroughs as a fraction of the number of impressions. |

An interactive measure of web advertising. Has great strengths, but clicks represent only a step toward conversion and are thus an intermediate advertising goal. |

Measure the effectiveness of a web advertisement by counting those customers who are sufficiently intrigued to click through it. |

11.4 |

Cost per Click |

Advertising cost divided by number of clicks generated. |

Often used as a billing mechanism. |

Measure or establish the cost-effectiveness of advertising. |

11.4 |

Cost per Order |

Advertising cost divided by number of orders generated. |

More directly related to profit than cost per click but less effective in measuring the impact of pure advertising. An advertisement may generate strong clickthrough but yield weak conversion due to a disappointing product. |

Measure or establish the cost-effectiveness of advertising. |

11.4 |

Cost per Impression |

Advertising cost, divided by number of customers acquired. |

Useful for purposes of comparison to customer lifetime value. Helps marketers determine whether customers are worth the cost of acquisition. |

Measure or establish the cost-effectiveness of advertising. |

11.5 |

Visits |

The number of times that visitors come to a website. |

By measuring visits relative to pageviews, marketers can determine whether viewers are investigating multiple pages on a website. |

Measure audience traffic on a website. |

11.5 |

Visitors |

The number of unique website visitors in a given period. |

Useful in determining the type of traffic generated by a website—a few loyal adherents or many occasional visitors. The period over which this metric is measured can be an important consideration. |

Measure the reach of a website. |

11.5 |

Abandonment Rate |

The rate of purchases started but not completed. |

Can warn of weak design in an e-commerce site by measuring the number of potential customers who lose patience with a transaction process or are surprised and put off by “hidden” costs revealed toward its conclusion. |

Measure one element of the close rate of an internet business. |

11.6 |

Bounce Rate (website) |

Fraction of website visitors who view only a single page. |

Requires a clear definition of when a visit ends. Usually considers bounce rate with respect to visits rather than visitors. |

Determine a site’s relevance and ability to generate visitor interest. |

11.7 |

Friends/Followers/Supporters |

Number of individuals joining a social network. |

Success depends on the target group and the social nature of the product. This metric is unlikely to reflect the ultimate aim of a marketing campaign. |

Measure the size of a social network (though not likely engagement). |

11.7 |

Likes |

Number who have favored a post/site/organization on social media. |

Measures engagement with the liked entity. Can be used to understand what posts resonate most with consumers. |

Understand the relative popularity of social media elements. |

11.7 |

Value of a Like |

A dollar value ascribed to each like, follower, and so on. |

Beware of causal claims. Consumers usually like a product on a social network because they favor the product offline. Merely generating likes won’t necessarily change purchase behavior. |

Find a dollar value for a like. (Do not use as a benchmark for spending on social media.) |

11.8 |

Downloads |

Number of times an application or a file is downloaded. |

Counts the times a file was downloaded, not the number of customers who downloaded a file. It is often useful to monitor downloads started but not completed. |

Determine effectiveness in getting applications out to users. |

11.9 |

Mobile Metrics |

Revenues divided by the number of users. |

May help to indicate how effective an app is at generating revenues, but cost figures are needed to establish profitability. |

Examine the effectiveness of an app at generating revenue from its user base. |

11.10 |

Email Clickthrough |

The clickthrough rate is the percentage of times an email is clicked on. |

Measures how effectively email gains attention. |

Determine the effectiveness of email campaigns. |

11.1Impressions and Pageviews

Purpose: To assess website traffic and activity.

To quantify the traffic a website generates, marketers monitor pageviews—the number of times a page on a website is accessed. In the early days of e-commerce, managers paid attention to the number of hits—or file requests—a website received. Because web pages are composed of numerous text, graphic, and multimedia files, the number of hits a page receives is a function not only of pageviews but also of the way those pages were composed by their web designer. As marketing on the internet became more sophisticated, better measures of web activity and traffic evolved. As hits can be influenced by web page design, this measure is not as helpful. Pageviews is a better measure of traffic.

The Pageviews metric aims to measure the number of times a page has been displayed to a user. It should be measured as close to the end user as possible. The best technology counts pixels returned to a server and confirms that a page was properly displayed. This pixel count technique1 yields numbers closer to the end user than would a tabulation of requests to the server or of pages sent from the server in response to a request. Good measurement can mitigate the problems of inflated counts due to servers not acting on requests, files failing to serve on a user’s machine, or users terminating the serving of ads.

Pageviews: The number of times a specific page has been displayed to users. This should be recorded as late in the page-delivery process as possible in order to get as close as possible to the user’s opportunity-to-see. A page can be composed of multiple files.

A further distinction needs to be made as to how many times an advertisement was viewed by unique visitors. A marketer is typically interested in how many people viewed an advertisement, and the technology used to serve different ads to different visitors is widely available. For example, two individuals entering a web page from two different countries might receive the page in their respective languages and will also probably receive different advertisements. One example of an advertisement that is commonly displayed differently to different visitors is an embedded link with a banner ad. Recognizing this potential for variation, advertisers want to know the number of times that their specific advertisement was displayed to visitors rather than just the site’s number of pageviews.

Internet advertisers often perform their analyses in terms of impressions—sometimes called ad impressions or ad views—which represent the number of times an advertisement is served to visitors, giving them opportunities to see it. (Many of the concepts in this section are in line with the terms covered in Chapter 10, “Advertising and Sponsorship Metrics.”) Of course, if a page carries multiple advertisements, the total number of all ad impressions will exceed the number of pageviews.

Major sites have an ad server involved in presenting advertisements. The ad server can control who sees what and may serve different ads to different visitors or multiple ads to a single visitor. This can get surprisingly complex, and technical issues—such as the page refreshing—may complicate the data. Given the variety of ways an advertisement can be seen, it can be challenging to reconcile the data between a site and an ad server.

There can be considerable controversy about the serving of advertisements. The Media Rating Council defines a viewable impression as an impression that might have been viewed from an impression that was were served for such a short period of time or in which so few of the pixels served that it should not count as an impression.2

Construction

Hits: A count of the number of files served to visitors on the web. Because pages often contain multiple files, Hits is a function not only of pages visited but also of the number of files on each page. We detail this metric given its historical significance, but hits are more relevant to technicians responsible for planning server capacity than to marketers interested in measuring visitor activity.

Hits (#) = Pageviews (#) * Files on the Page (#)

Pageviews: The number of pageviews can be easily calculated by dividing the number of hits by the number of files on the page.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Pageviews, page impressions, and ad impressions are measures of the responses of a web server to page and ad requests from users’ browsers, filtered to remove robotic activity and error codes prior to reporting. These measures are recorded as close as possible to the user’s opportunity to see the page or ad to most accurately capture the opportunities.3

For very simple websites, a count of ad impressions can be derived from pageviews if the percentage of pageviews that contain the ad in question is known. For example, if 10% of pageviews receive the advertisement for a luxury car, then the impressions for that car ad will equal 10% of pageviews. Simple websites that serve the same advertisement to all web users are easy to monitor, but for most marketers working in major firms, life is more challenging. They typically work with ad servers that have their own reporting systems to cope with the measurement problems.

The impression-based metrics quantify opportunities-to-see; they do not take into account the number of ads actually seen or the quality of what is shown. In particular, these metrics do not account for the following:

Whether the message appeared to a specific, relevant, defined audience.

Whether the people to whom the pages appeared actually looked at them.

Whether the advertisement was clearly visible. The term “below the fold,” borrowed from the newspaper world, is used to describe advertisements on a page that are not visible in the initial display of the page. Generally, if visitors must scroll to see the advertisement, they are less likely to be influenced by it.

Whether those who looked at the page had any recall of the page’s content or of any advertising messages contained on it after the event.

Despite the use of the term impression, these measures do not tell a business manager about the effect that an advertisement has on potential customers—that is, whether the advertisement actually made an impression on the potential customer. Marketers can’t be sure of the effect that pageviews have on visitors.

Finally, pageview results often consist of data that include duplicate showings to the same visitor. For this reason, the term gross impressions may be used instead to highlight what is often a key point—that opportunities-to-see may be delivered to the same viewer on multiple occasions.

11.2Media Display Time and Interaction Rate

Purpose: To determine how an advertisement engages viewers.

Rich media is a term used for interactive media that allow consumers to be more actively engaged than they might be with a billboard, a TV advertisement, or even a static display web advertisement. Rich media (or just media) metrics and audience interaction metrics are very similar in principle to other advertising metrics. Marketers want to track whether an advertisement is effective at grabbing and maintaining the attention of potential customers, and so they track how long people spend viewing an advertisement as a proxy for how interested they are in the content of the advertisement. The Media Display Time metric shows how long, on average, people spend engaged with the media.

The Media Interaction Rate metric tracks how actively involved potential consumers are with an advertisement. The big advantage of media is the ability of viewers to interact with it. Marketers using media can get a much better idea of potential customers’ reactions to an advertisement simply because these interactions are counted. They can monitor whether potential customers are simply passively “viewing” the media on their screens or are actively engaged by taking some traceable action. A user who interacts is showing evidence of being more actively engaged and is thus probably more likely to move toward purchase.

Construction

Average Media Display Time: The average time that viewers spent with the media of an advertisement. For this metric, the marketer needs the total amount of time spent with the media and the total number of times that the media was displayed. It is a simple matter to create an average time in seconds spent with the media by dividing the total amount of time in seconds spent by the total number of impressions.

Media Interaction Rate: The number of impressions of an advertisement that were interacted with divided by the total number of impressions of that advertisement. This metric tells marketers how successful any advertisement was at getting potential customers to engage with it in some way (for example, rolling the mouse over, clicking, deliberately starting a video). As an example, a media advertisement that was displayed 100 times with an interaction rate of 15% would mean that 15 of the impressions resulted in some kind of interaction, and 85 resulted in no interaction.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

With many web-based metrics, data often seem abundant to marketers who come from the offline world. However, there are several measurement issues a marketer must address in order to convert the abundance of data into useful metrics (that is, to information and eventually to knowledge). For example, marketers usually cut off display times at some upper bound; for example, if a piece of media has been displayed for five minutes, a marketer may think it is safe to assume that the viewer has probably gone to make a cup of coffee or been otherwise distracted. The question of how long a displayed piece of media was actually viewed has some similarities to the question offline marketers face with respect to whether an offline advertisement was viewed. A slight advantage here goes to the online media in that most displays of media begin because of an active request of the viewer, whereas no such action is required offline.

Media display time, because it usually occurs for only short periods, can be influenced by unusual events. For example, if five people see a media display for 1 second each, and one person sees it for 55 seconds, the (average) media display time is 10 seconds. There is no way to distinguish this average display time from the average time generated by six moderately interested viewers each viewing the advertisement for 10 seconds. Such is the case with any average.

Marketers should clearly understand how the data were gathered and should be especially aware of any changes in the way the data were gathered. Changes in the way the data are gathered and in how the metric is constructed may be necessary for technological reasons but will limit the usefulness of the metric as longitudinal comparisons (that is, over time) lose their validity. At a minimum, a marketer must be aware of and account for measurement changes when interpreting such a metric.

Data for the Media Interaction Rate are typically available. Indeed, the metric itself might be reported as part of a standard reporting package. One important decision that has to be made in generating the metric is what counts as an interaction. The answer depends on the potential actions that the viewers could take, which in turn depends on the precise form of the advertisement. What counts as an interaction usually has some lower bound. For example, an interaction is counted only if the visitor spends more than one second with a mouse over the impression. (This guideline is designed to exclude movements of the mouse unrelated to the advertisement, such as moving the mouse over the advertisement to another part of the page.)

As is true of any advertising, marketers should not forget the goal of their advertising. Interaction is unlikely to be an end in itself. As such, a larger interaction rate, which might be secured by gimmicks that appeal to people who will never buy the product, may be no better than a smaller rate if the larger rate doesn’t move the visitor closer to a sale (or some other high-order objective).

Related Metrics and Concepts

Media Interaction Time: The total amount of time that a visitor spends interacting with an advertisement. This is an accumulation of the total time spent interacting per visit on a single page. On a visit to a page, a user might interact with the media for two interactions of two seconds each and so have an interaction time of four seconds.

Video Interactions: Video metrics are very similar to media metrics. Indeed, video can be classified as media, depending on the way it is served to the viewer. Similar principles apply, and a marketer should track how long viewers engage with the video (that is, the amount of time the video plays), what viewers do with the video (for example, pause it, mute it), and the total and specific interactions with the video (which show evidence of attention to the video). Such metrics are then summarized across the entire pool of visitors (for instance, the average visit might have led to the video being played for 12 seconds).

11.3Clickthrough Rates

Purpose: To capture customers’ initial response to websites.

Most commercial websites are designed to elicit some sort of action, whether it be to buy a book, read a news article, watch a music video, or search for a flight. People generally don’t visit a website with the intention of viewing advertisements, just as people rarely watch TV with the purpose of consuming commercials. As marketers, we want to know the reaction of a web visitor. Under current technology, it is nearly impossible to fully quantify the emotional reaction to a site and the effect of that site on a firm’s brand. One piece of information that is easy to acquire, however, is the clickthrough rate. The clickthrough rate measures the proportion of impressions that led to an initiated action with respect to an advertisement that redirected the visitor to another page, where the visitor might purchase an item or learn more about a product or service. Here we have discussed clicking on an advertisement (or link), but other interactions are possible. The consumer may access via a variety of smart technologies.

Construction

Clickthrough Rate: The number of times a click is made on an advertisement divided by the total impressions (the times an advertisement was served).

Clickthroughs: If you have the clickthrough rate and the number of impressions, you can calculate the absolute number of clickthroughs by multiplying the clickthrough rate by the impressions.

Clickthroughs (#) = Clickthrough Rate (%) * Impressions (#)

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

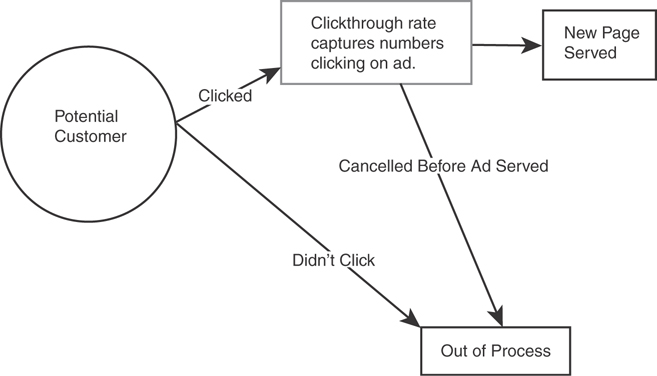

The number of impressions is a necessary input for the calculation of clickthrough rate. On the very simplest websites, this is likely to be the same as pageviews; every time the page is accessed, it shows the same details. On more sophisticated sites, different advertisements can be shown to different viewers, meaning the number of impressions of the advertisement cannot simply be estimated from the number of pageviews. The good news is that this metric is usually available as part of a reporting package. For clickthrough rate, you also need clicks, and the server can easily record the number of times the link was clicked (see Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1 Clickthrough Process

Remember that the clickthrough rate is expressed as a percentage. Although high clickthrough rates might in themselves be desirable and might help validate an ad’s appeal, companies are also interested in the total number of people who clicked through. Imagine a website with a clickthrough rate of 80%. It might seem like a highly successful website until management discovers that only 20 people visited the site. Rather than see the 80% clickthrough rate as healthy, markets might do better to compare the resulting 16 potential customers who clicked through with management’s stated objective of 500 clickthroughs.

Also remember that a click is a very weak signal of interest. Individuals who click on an ad might move on to something else even before the new page is loaded. A user might click on an advertisement by accident, or the page might take too long to load, prompting the user to click it. This problem has become significant with the increase in richer media advertisements. Marketers should understand whether their customers are using devices that are able to quickly display the requested file. Using large video files is likely to increase the number of people abandoning the process before the ad is served, especially if the potential customers have relatively slow connections.

As with impressions, try to ensure that you understand the measures. If the measure is of clicks (the requests received from client machines to the server to send a file), then there may be a number of breakage points between the click and the impressions of the ad generated from a returned pixel count. Large discrepancies should be understood: What role is played by technical problems (such as the size/design of the advertisement), and what is the role of weak interest from clickers?

Clicks are the number of times an advertisement was interacted with, not the number of customers who clicked. An individual visitor can click on an ad several times—either in a single session or across multiple sessions. You need to investigate your web analytics package to get a deeper understanding such as how many times an ad was clicked on by someone using the same browser. Furthermore, sophisticated websites can control the number of times they show a specific advertisement to the same customer. (A customer who logs onto a site can be tracked, which gives a marketer more information on what the person sees.) Finally, the clickthrough rate must be interpreted relative to an appropriate baseline. Clickthrough rates for banner ads are very low and continue to fall. In contrast, clickthrough rates for buttons that simply take visitors to the next page on a site should be much higher. An analysis of how clickthrough rates change as visitors navigate through various pages can help identify “dead end” pages that visitors rarely move beyond.

One can test the effectiveness of various web page designs by serving different pages randomly. The random serving of pages, when done correctly, allows a marketer to assume that those viewing the page are similar, and any differences in reaction can thus be attributed to differences in the web design.

It is possible to test a range of different sites and variations of content on the sites easily. The tests used for this are commonly known as A/B tests, or multivariate tests when there is more than one difference. Many tools that are available to help run these tests (for example, Unbounce) are affordable for a wide variety of organizations. In general, best practice is to test to find the best version of a web page or advertisement possible.

One useful approach is to classify metrics such as clickthroughs as micro-conversions on the path to the macro-conversion—an eventual purchase. The aim of a firm is not to generate clickthroughs (the micro-conversions), but the micro-conversions are a necessary stage in attaining the final aim, the macro-conversion. Describing them as macro- and micro-conversions helps keep the focus on the macro-conversion—the ultimate goal. It is still important to realize that failing on micro goals tends to mean you will ultimately fail on the macro goal.

11.4Cost per Impression, Cost per Click, and Cost per Order

Purpose: To assess the cost-effectiveness of Internet marketing.

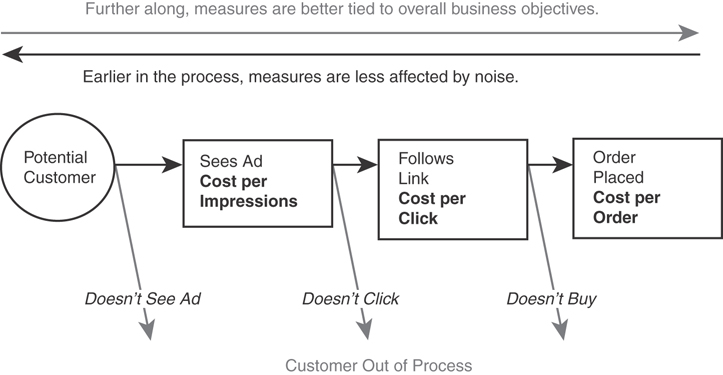

In this section, we present three common ways of measuring the cost-effectiveness of Internet advertising. Each has benefits, depending on the perspective and end goal of the advertising activity.

Cost per Impression gives the cost to offer potential customers one opportunity to see an advertisement. CPM is the more commonly used version of Cost per Impression. It is the same metric but using per thousand impressions as the denominator. (For some reason technical people like to use mille, the Latin for “thousand,” hence the M in CPM.)

Cost per Click gives the average amount spent to get an advertisement clicked. Cost per Click has a big advantage over Cost per Impression in that it tells something about how effective the advertising was. Clicks provide a way to measure attention and interest. An advertisement may look inexpensive in that it has a relatively low CPM. Of course, if an advertisement isn’t relevant, it will end up with few clicks and therefore a high cost per click. Badly targeted advertisements can be very expensive, as measured by Cost per Click. If the main purpose of an ad is to generate a click, then Cost per Click is the preferred metric.

Cost per Order gives the average cost to acquire an order. If the main purpose of an ad is to generate sales, then Cost per Order is the preferred metric.

A certain number of web impressions need to be achieved to generate a reasonable number of orders, and the quality and placement of the advertisement will affect both click(through) rates and the resulting cost per click (see Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 The Order Acquisition Process

Construction

The formulas are essentially the same for the metrics Cost per Impression, Cost per Click, and Cost per Order: Just divide the advertising cost by the appropriate number of impressions, clicks, or orders.

Cost per Impression: Derived from advertising cost and the number of impressions. Cost per impression is typically expressed as cost per thousand impressions (CPM) in order to make the numbers easier to manage. (For more on CPM, refer to Section 10.2.)

Cost per Click: Calculated by dividing the advertising cost by the number of clicks generated by the advertisement.

Cost per Order: The cost to generate an order. The precise form of this cost depends on the industry and is complicated by product returns and multiple sales channels. That said, the basic formula is

Cost per Customer Acquired: Divide the advertising cost by the number of new customers who make an order. Refer to Chapter 5, “Customer Profitability,” for more on defining customer and acquisition costs.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

The Internet has provided greater availability of advertising data. Consequently, Internet advertising metrics are likely to rely on data that is more readily obtainable than data from conventional channels. The Internet can provide more information about how customers move through the system and how individual customers behave at the purchase stage of the process.

The calculations and data we have discussed in this section are often used in contracts compensating advertisers. Companies may prefer to compensate media and ad agencies on the basis of new customers acquired instead of impressions, although the agencies may be less happy as this pushes more risk onto the agency. The agency may find its efforts limited by the lack of appeal of the client’s products rather than the agency’s efforts to produce interesting advertising and get it widely distributed.

Search Engines

Search engine payments help determine the placement of links on search results pages. An important search engine metric is Cost per Click, and it is generally the basis for establishing the search engine placement fee. Search engines can provide plenty of data to analyze the effectiveness of a campaign. In order to reap the benefits of a great site, a firm needs to get people to visit it. Previously we discussed how firms measure traffic. Search engines help firms create that traffic.

Although a strong brand helps drive traffic to a firm’s site, including the firm’s web address in all of its offline advertising might not be sufficient to increase traffic. In order to generate additional traffic, firms often turn to search engines. EMarketer estimated that social network spending reached $16.1 billion in 2019. Furthermore, $350 billion was spent on paid media in 2019 overall in the United States. Digital spending accounted for a significant 36.8% of this total.4

Paid search marketing (also known as search engine marketing) is essentially paying for the placement of ads on search engines across the Internet. The ads are typically small portions of text (much like newspaper want ads) made to look like the results of an unpaid or organic search. Payment is usually made only when someone clicks on the ad. It is possible to pay more per click in return for better placement on the search results page. Advertisers can bid to be displayed whenever someone searches for specified keyword(s). In this case, companies bid on the basis of Cost per Click. Bidding a higher amount per click gets you placed higher. However, there is an added complexity: If the ad fails to generate several clicks, its placement will be lowered in comparison to competing ads, despite a higher Cost per Click bid.

The measures for testing search engine effectiveness are largely the same as those used in assessing other Internet advertising.

Cost per Click

Cost per Click is widely quoted and used by search engines in charging for their services. Marketers use Cost per Click to build their budgets for search engine payments.

Search engines ask for a “maximum Cost per Click,” which is a ceiling whereby marketers impose the maximum amount they are willing to pay for an individual click. A search engine typically auctions the placement of links and only charges for a click at a rate just above the next highest bid. This means the maximum Cost per Click that a company would be willing to pay can be considerably higher than the average Cost per Click it ends up paying.

Marketers often talk about the concept of daily spend on search engines: the total spent on paid search engine advertising during one day. In order to control spending, search engines allow marketers to specify maximum daily spends. When the maximum is reached, the advertisement doesn’t show again until the next 24-hour period.

Daily spend can be thought of as the product of average cost per click and the number of clicks:

Daily Spend ($) = Average Cost per Click ($) * Number of Clicks (#)

Ad Rank

Ad rank is the position of an advertisement served on a Pay per Click (PPC) basis on a search engine. The rank depends on the amount bid for each keyword as well as the relevance of the keywords, which determines the quality and ranking.

Search engines typically use auctions to establish prices for the search terms they sell and have the great advantage of having a relatively efficient market; all users have access to the information and can be in the same virtual location. Search engines tend to adopt a variant on the second price auction. Buyers pay only the amount needed for their requested placement; as such, search engine marketers can control the price they are willing to pay. The trick therefore is to know how much is reasonable for your firm to pay per click, which ultimately is a managerial judgment based on the benefits you expect to receive (for example, customers generated).

Search Engine Optimization

Search engine optimization involves efforts to get your website to rank more highly on search engines’ organic (unpaid) search results. There is little reason not to try to improve your ranking on organic search. In practice, successful search engine optimization involves considerable skill and knowledge of how the rankings are constructed. The search engines have a variety of algorithms for ranking sites. Possibly the most famous is Google’s PageRank, which works by counting the number and quality of links to a page to arrive at a rough estimate of how important the website is.

11.5Visits, Visitors, and Abandonment

Purpose: To understand website user behavior.

Websites can easily track the number of pages requested. As we saw in Section 11.1, the Pageviews metric can be useful but is far from a complete metric. We can do better. In addition to counting the number of pageviews a website delivers, firms also often count the number of times someone visits the website and the number of people requesting those pages.

To get a better understanding of traffic on a website, companies attempt to track the number of visits. A visit (known as a “session” in Google Analytics) can consist of a single pageview or multiple pageviews, and one individual can make multiple visits to a website. Visits captures the number of times individuals request a page from a website for the first time (that is, the first request triggers the visit). Subsequent requests from the same individual do not count as visits unless they occur after a specified timeout period. The exact specification of what constitutes a visit requires this accepted standard for a timeout period, usually set at 30 minutes, which is the number of minutes of inactivity from the time of entering the page to the time of requesting a new page.

In addition to tracking visits, firms also attempt to track the number of individual visitors to their websites. The Visitors (or Unique Visitors) metric captures the number of individuals requesting pages from the firm’s website server during a given period. Google Analytics refers to these individuals as “users.” Because a visitor can make multiple visits in a specified period, the number of visits is greater than the number of visitors. A visitor is sometimes referred to as a unique visitor or unique user to clearly convey the idea that each visitor is counted only once.

The number of users or visitors must be measured over a time period, such as the number of visitors in a given month.

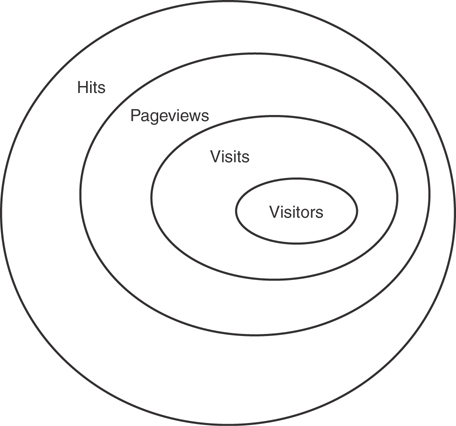

Pageviews and visits are related. By definition, a visit is a series of pageviews grouped together in a single session, so the number of pageviews exceeds the number of visits.

Consider the metrics Visitors, Visits, Pageviews, and Hits as a series of concentric ovals, as shown in Figure 11.3. In this view, the number of visitors must be less than or equal to the number of visits, which must be less than or equal to the number of pageviews, which must be equal to or less than the number of hits. (Refer to Section 11.1 for details of the relationship between hits and pageviews.)

Figure 11.3 Relationship of Hits to Pageviews to Visits to Visitors

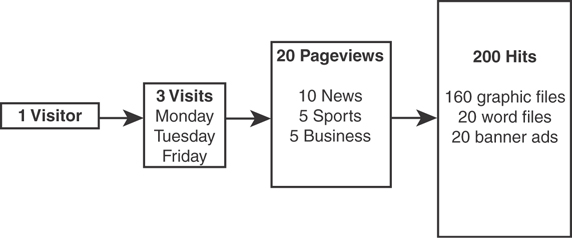

Another way to consider the relationship between Visitors, Visits, Pageviews, and Hits is to consider an example of a visitor entering the website of an online newspaper (see Figure 11.4). Suppose that the visitor enters the site on Monday, Tuesday, and Friday. In her visits, she looks at a total of 20 pageviews. Those pages are made up of a number of different graphic files, word files, and banner ads.

Figure 11.4 Example of Online Newspaper Visitor

The ratio of pageviews to visitors is sometimes referred to as the average pages per visit. Marketers track this average to monitor how the average visit length changes over time.

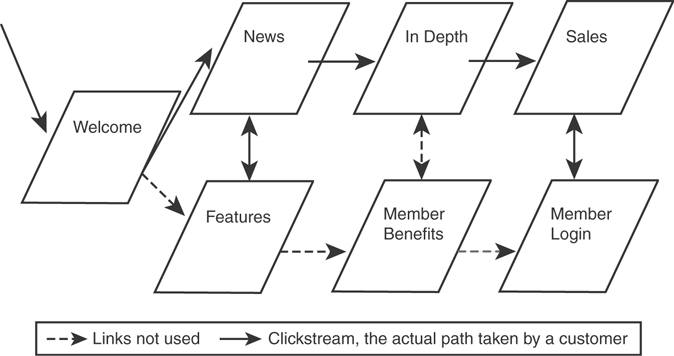

It is possible to dig even deeper and track the paths visitors take. This path is called the clickstream.

Clickstream: The path of a user through the Internet.

The clickstream refers to the sequence of clicked links the user makes. By using the clickstream on his or her own site, a marketer tracking at this level can help the firm identify the most and least appealing pages (see Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.5 A Clickstream Documented

The analysis of clickstream data often yields significant customer insights. What path is a customer most likely to take prior to purchase? Is there a way to make the most popular paths even easier to navigate? Should the unpopular paths be changed or even eliminated? Do purchases come at the end of lengthy or short sessions? At what pages do sessions end?

A portion of the clickstream that deserves considerable attention is the subset of clicks associated with the use of shopping carts. A shopping cart is a piece of software on a server that allows visitors to select items for eventual purchase. Although shoppers in brick-and-mortar stores rarely abandon their carts, abandonment of virtual shopping carts is quite common. Savvy marketers count how many of the shopping carts used in a specified period result in a completed sales versus how many were abandoned. The ratio of the number of abandoned shopping carts to the total is the abandonment rate.

Construction

Visits and Visitors: Your analytics system will probably report these figures. Cookies can help servers track unique visitors, but this data is never 100% accurate (see the next section).

Abandonment Rate: The percentage of carts that were abandoned before completion.

Conversion Rate: Many marketers monitor their conversion rate, the percentage of visitors who actually buy. This gives a good headline view of how effective a website is at generating sales once it has visitors.

Google Analytics uses Sessions as the denominator in this equation. This means that each consumer can convert more than once by visiting more than once. Be careful to understand which denominator your data represent.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Visits can be estimated from log file data. Visitors are much more difficult to measure.

Companies often encourage users to register on their websites so they can gain a better understanding of their users. Often consumers aren’t keen to do so—perhaps because they see registering as a hassle or as limiting their privacy. Indeed, marketers rarely know for certain that a user is unique. Instead, they consider visits from new browsers evidence of a new user and return visits from the same browser as returning visitors. This means a user who uses different devices will often show as two different users. Similarly, different people may show as the same user (for instance, when a family shares a computer).

To decide whether a visitor is a returning visitor or a new user, companies often employ cookies. A cookie is a file downloaded onto the computer of a person surfing the web that contains identifying information. When the browser returns, the web server reads the cookie and recognizes the visitor as someone who has been to the website previously. More advanced sites use cookies to offer customized content, and shopping carts make use of cookies to distinguish one shopping cart from another. For example, Amazon, eBay, and easyJet all make extensive use of cookies to personalize the web views to each customer. As users become more sophisticated, many are trying to protect their anonymity by using VPNs and by not allowing cookies or deleting them regularly. If visitors accept cookies, then at least the browser that was used for a visit can be identified. If customers do not accept cookies, this is much harder, and it can be a significant problem for a marketer’s operations.

Cookie: A small file that a website puts on the hard drive of a visitor for the purpose of future identification.

These metrics can be distorted by automatic activity (such as “bots”) that aim to classify web content. To prevent this, estimates of visitors, visits, and other traffic statistics are usually filtered to remove this activity by eliminating known IP addresses for “bots,” by requiring registration or cookies, or by using panel data.

Consultants may be able to help quantify your activity. For example, Nielsen, among other services, runs a panel in the United States and a number of other major economies.5

11.6Bounce Rate (website)

Purpose: To determine the effectiveness of the website at generating the interest of visitors.

Bounce Rate is a commonly reported metric that reflects the effectiveness of websites at drawing the continuing attention of visitors. The assumption behind the usefulness of the metric is that the owner of the website wants visitors to visit more than just the landing page. For most sites, this is a reasonable assumption. For example, sites that are seeking to sell goods want visitors to go to other pages to view the goods and ultimately make a purchase. Bounce Rate is also a measure of how effective the company is at generating relevant traffic. The more a website is relevant to the traffic coming to it, the lower the Bounce Rate. This becomes particularly important when traffic is generated through paid search. Money spent to generate traffic for whom the website is not relevant (as reflected in a high Bounce Rate) is money wasted. The Bounce Rate is a particularly useful measure with respect to the entry pages to websites. An entry page with a very low Bounce Rate may be thought of as doing its job of driving traffic to other pages, but the actual rate depends on a number of factors. As Google Analytics explains, “Evaluate and adjust factors that might contribute to your bounce rate, like site layout and navigation. Use only your past performances as a rubric, and try to improve your current bounce rate relative to your previous data. Provide enough time between changes to collect enough data to evaluate the impact the changes may be having on your users and their behaviors. Try using Content Experiments to help you.”6 A content experiment, similar to an A/B test, involves showing different pages to different visits (ideally randomly selected) and seeing which page performs best.

A low Bounce Rate is often a prerequisite for a successful e-commerce presence.

Construction

Bounce Rate: The number of visits that access only a single page of a website divided by the total number of visits to the website.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Data to construct the Bounce Rate metric, or even the metric itself, usually come from a website’s host as part of the normal reporting procedure. Given how common it is that Bounce Rate is reported by default, it is a metric that is difficult to ignore. Construction of the metric requires a precise definition of when a visit ends. Leaving the site may be based on closing the window, hitting the Back button, or being timed out. (Google Analytics counts session timeouts.) After a timeout, a new session is usually started if the visitor returns to the website. A lower timeout period results in increased bounce rates, all else equal.

Reports may use the term visitors instead of visits. You should be clear what data are actually reported. Visits are much easier to track than visitors because when the same visitor makes return visits, especially to different entry pages, it can be difficult to connect the return visit to the original visitor. As such, visits is more likely than visitors to be used to calculate Bounce Rate.

This metric can also be defined and constructed for individual landing pages within a site. Indeed, the Bounce Rate for each landing page allows for more precise diagnosis of problem areas on a website. One must interpret Bounce Rate for a page, however, in light of the purpose of the page. For some pages, such as directions pages, where people go to find out specific information, a high Bounce Rate is to be expected.

The value of the Bounce Rate metric depends on the objective of the organization. Informational sites may develop a strong bond with their users through frequent short interactions, such as when the users check sports scores. Such an organization may be comfortable if many users do not visit other parts of the site and may not be too concerned about a high Bounce Rate. However, most companies are likely to want their Bounce Rate to be low and to actively monitor this important metric.

One of the most challenging problems in marketing (online, offline, and online to offline) is the problem of attribution. A consumer is likely to have been reached by multiple marketing actions prior to his or her purchase, and it can be impossible to say definitively which touchpoint generated a sale. Indeed, all touchpoints may have had vital contributions to generating a sale. For advertisers using a mix of online and offline media, it is especially difficult to categorize the cause-and-effect relationships between advertising and sales. Search ads might receive too much credit for an order if the customer has also been influenced by the fact that the consumer earlier saw the firm’s billboard advertisement. Conversely, search ads might receive too little credit for offline sales where the consumer’s interest was previously piqued by the search ad. Similarly, social media can sometimes play a big role in sales, assisting the final conversion but usually not as the last referral source clicked before a purchase. Given this, social media doesn’t always get the credit it deserves for driving sales.

Attribution is challenging, but various assumptions are made. When all items influencing a purchase are online, a firm can attribute the sale in a number of ways.

With last-click attribution, full credit for a sale is given to the final touchpoint prior to purchase. With first-click attribution, full credit for a sale is given to the initial touchpoint—that is, the first contact on the customer’s path to purchase. With linear attribution, the credit is shared equally between all touchpoints involved in the path to purchase. Clearly, it is hard to defend any of these assumptions as perfectly capturing what happens in the real world, but understanding the assumptions is necessary in determining whether the assumptions are useful approximations of reality even if they never perfectly capture reality.

Google Analytics

The tools Google has made available can help you understand the success of your marketing on a wide range of platforms. Google supplies an extensive range of assistance to those wishing to use Google Analytics. This material, which includes graded courses to work through, is supplied at the Google Analytics Academy, analyticsacademy.withgoogle.com/explorer.

11.7Social Media Metrics: Friends/Followers/Supporters/Likes

Purpose: To determine the effectiveness of a social networking presence.

Marketers want people to care about their brands and products. Various measures of engagement with a brand’s social media presence indicate users’ level of care.

We use the term friends to encompass followers, supporters, and other similar concepts. Friends are members of a social networking site who register that they know, like, and/or support the owner of the social networking page. For instance, a strong brand might have many customers who want to publicly signal their love of the brand. Social networking sites offer great benefits in allowing companies to develop customer relationships and can help a company identify and communicate with committed customers.

Likes are ways that individuals on social media show they favor a post or a page. They click on a like button for a page, comment, brand, and so on. Like is an extremely low commitment activity, and some people like many things in a day. It seems, however, a reasonable assumption that generally a larger number of likes is indicative of greater appeal.

Construction

The Friends and Likes metrics are supplied by a social network.

Friends (#): The number of friends of the entity registered on a social network.

Likes (#): The number of individuals favoring a social networking post/page.

Cost per Friend (Like): The cost to the organization per friend recruited or Like generated.

Often the direct costs of having a social networking site are very low. This should not, however, lead a marketer to conclude that the cost is effectively zero. A site has to be designed, staff have to update the site, and marketers have to devise strategies. Remember when calculating the cost of having a social network presence that the cost should include all costs incurred in the provision of the social network presence.

Outcomes per Friend: The precise downstream outcomes gained by the presence of friends. It is often very hard to track and attribute outcomes (“Did we sell more ketchup?”) to specific social networking actions. This does not mean that an active social networking presence is not a vital part of an Internet marketing strategy; when designing a presence, the ultimate objective of the company needs to be borne in mind. For example, friends are often recruited to “vote” in polls. The percentage of friends participating is a simple example of an Outcome per Friend metric but is probably not the ultimate objective.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Success in recruiting friends is likely to depend heavily on the group of people who identify with the entity (for example, individuals, brands, companies, other groups). In the case of brands, some customer segments are more reluctant to reveal their brand loyalty than others, and therefore two brands of equivalent strength may have very different levels of social network presence. Similarly, the product involved is likely to influence the likelihood of registering as a friend at the social networking site. It is easy to think of some vitally important but more private products that are relied upon by their users but are less likely to gain public expressions of support than brands that are more related to public consumption.

It is very hard to objectively judge the effectiveness of social networking activities. Generally, having more followers or likes is an excellent sign of customer engagement. The more customers who have an ongoing relationship with a brand that they are willing to publicly support, the more likely the brand is to have strong customer awareness and loyalty. It is worth noting, however, that Friends and Likes, as with many other metrics, are most often intermediate metrics rather than an aim of an organization. It is unlikely that most organizations exist with the explicit objective of generating Friends. As such, it is rarely sufficient to report the number of Friends as a successful outcome of a marketing strategy without any additional information. This concern is only increased by the widespread practice of selling Friends and Followers on social media. Likes need to be tied to the objectives of the firm and should not just be a way of soothing the vanity of the marketer.

It is often appropriate to construct metrics around the downstream outcomes and cost-effectiveness of such strategies. A marketer would be well advised to pay attention to the costs and ultimate benefits of social networking presence as well as the clear potential to engage with customers.

The number of social networking posts that are engaged with may indicate successful engagement. A firm might therefore measure the number of posts that generate response divided by the total number of posts to give some idea of engagement with the social network.

Marketers may attempt to put a dollar value on social media. It is possible to calculate the value of a like as the difference between the value of someone who doesn’t like a brand (for example) and someone who does. Value of a Like (or Value of a Follow) is sometimes calculated by subtracting the value of an individual consumer who did not choose to like (or follow) a brand from the value of an individual who did. It is important to note that it would be incorrect to argue that this difference is the value attributable to the social media strategy. It is unlikely that the social media strategy caused the entire difference in value observed between those choosing to like the brand and those not doing so. There are likely a number of other factors.

There are, thus, two major caveats that we have seen with the use of the Value of a Like metric, which leads to concern that Value of a Like can cause more harm than good. First, value to a firm should be the profit generated by the consumer and not revenue. Assessing Value of a Like as the revenue coming from consumers who like the firm overstates the value of a social media strategy as it ignores all the other costs of servicing these customers. Second, it is important to understand that this metric is not the amount that the organization can spend in order to secure a like (follower). Those who interact (positively) with a firm on social media are likely to already be positively predisposed to the firm. Encouraging other members of the public, who don’t have the same prior positive predisposition, by, for example, rewarding those who follow a brand on social media, is unlikely to change the new recruits’ purchase behaviors to resemble that of the more avid followers who followed without the incentive. When the difference in value is not caused by the social media strategy, it would be a mistake to use this as a benchmark for social media spending. Therefore, although Value of a Like is potentially an interesting number, the practical benefits of the metric are more limited than they might first appear.

Related Metrics and Concepts

Engagement Rate (%): A measure of engagement (Friends, Likes, and so on) divided by the impressions served. For example, Engagement Rate might show what proportion of those who had the opportunity to see a social media post liked it.

Engagement Rate (%) = Engagement (#)/Impressions (#)

Advocacy is exhibited when a consumer positively supports a brand or firm. The consumer might post a review of a brand or just give it a positive rating. The primary benefits of advocacy go to the brand or firm being advocated for, but other benefits exist. The subsidiary benefits of advocacy can go both ways. A retailer can benefit from consumers who advocate for a brand that is stocked in its store. Such advocacy can drive traffic to the retailer. Similarly, advocacy for the retailer helps the suppliers whose brands are sold in the retailer’s stores to improve their sales.

Advocacy (#, %): The number of positive reviews a brand receives. This metric can also be expressed as a percentage by dividing the number of reviews that are positive by the total number of reviews.

11.8Downloads

Purpose: To determine effectiveness in getting applications out to users.

Downloads—for applications for mobile phones, for MP3-style devices, and computers—are a common way for marketers to gain a presence with consumers.

Apps for iPhones, software trials, spreadsheets, ring tones, white papers, pictures, and widgets are examples of downloads. Such downloads typically provide benefit to a consumer in return for a presence on the device of the user. For instance, a weather app might be branded with the website of a particular TV channel and provide updates on atmospheric conditions. A consumer packaged goods company might supply an app that suggests recipes that use its products in novel ways.

Construction

The Downloads metric is supplied by analytics software.

Downloads (#): The number of times that an application or file is downloaded.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Downloads is a simple count of the number of times an application or a file is downloaded, regardless of who requested the download. It does not distinguish 10 identical downloads to a given individual from 10 separate downloads to 10 separate individuals, although these two situations may have dramatically different outcomes. In this way, Downloads is akin to Impressions, where a given number of impressions can be obtained through a variety of combinations of reach and frequency (see Section 10.3). Using your analytics package to see the number of downloads in unique sessions versus the total downloads should help you get a better feel for how many downloads were made by the same person. (Technically, this is often measured as downloads made by the same browser.)

A consideration in the counting of downloads is how to handle downloads that are started but not completed. One alternative is to keep track of both downloads started and downloads completed; another alternative is to pick one or the other (starts or completions) and use that measure consistently. As always, it is imperative for the user to know which convention was used in construction of the metric.

A further challenge is that downloads often raise problems in standard web analytics packages. This is because they often don’t fire a pageview when they provide a file (for example, a .pdf, .doc, or .xls file). This means downloads can’t be tracked as pages are. Downloads instead need to be tracked with event tracking, and event tracking involves code that creates a virtual pageview when an event is triggered.

11.9Mobile Metrics

Many issues in mobile marketing are similar to those in marketing aimed at users on computers. (Mobile relates to marketing using platforms optimized for use on handheld and other portable devices.) Mobile site metrics are similar to website metrics and can use web analytics packages such as the specialized mobile version of metrics on Google Analytics. These metrics allow you to better understand the users’ interactions and experience with the mobile site. While the metrics may be similar to traditional website measures, one would expect the results to differ by channel to reflect, for example, the relative strengths of desktop and mobile search. Mobile marketing might lead to fewer sales on the devices but might have a greater role in providing support to the sale, such as downloads of coupons or store maps. (Clearly there may be challenges attributing credit for sales between the mobile site, the website, and the brick-and-mortar store.)

Your analytics package is likely to be able to tell you where your traffic is coming from (for example, 80% desktop and 20% mobile). Given the problems with making attributions, this is only a useful—but clearly far from complete—view of the reliance of your marketing on various platforms (the environment the software runs on).

The second strand of mobile marketing might be the use of apps. Ensuring that apps are downloaded is an element of mobile marketing. Once you have an installed user base, you will want to check how you are acquiring customers, how they use the app, and how long customers stay with you.

A marketer should be aware of the percentage of customers using mobile payments. Marketers should also monitor mobile coupons used. The principles are similar to those in the non-mobile world, but the data from mobile devices are rich and relatively clean. For example, people usually operate only their own personal phone, whereas people are more likely to share computers.

Construction

Here we highlight a selection of metrics related to mobile apps.

Session Length: The length of time a user spends on an app.

Active Users (Monthly/Daily): The count of users who use the app during a given period (for example, a month, a day).

New User Acquisition and Retention Rate are similar to the metrics highlighted in Chapter 5. Retention can often be for a much shorter period in the world of mobile games, so it may be more appropriate to measure retention by the day rather than by the year.

Average Revenue per User: The effectiveness of a marketer at gaining revenue from each user. Clearly, the importance of this metric depends on the purpose of the app. An app that is designed to build a brand or facilitate usage of a product may have no revenue associated with it, but this does not mean it is not a valuable part of the marketing strategy.

Store Visits: A number of emerging applications meld the online and offline worlds. For example, store visits can be estimated using location-based tracking on mobile phones. This is anonymized data, so you can estimate the number of consumers who went to the stores—not which customers went there. When you have the number of consumers going into a store, you can compare this to an online action (for example, the number who downloaded a coupon) to assess how effectively the online strategy drives offline actions (for example, visits to stores).

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

Many of the key bits of data needed to assess mobile metrics come from analytics packages, such as Google’s Mobile analytics package.

While many of these concepts are the same across platforms, it is worth noting just how quickly the mobile market changes. In many areas, you might expect to see a payback to an investment in a few years. In mobile marketing, payback often needs to be much quicker. If a downloaded app doesn’t pay back in weeks, it may never do so. The active lives of users of mobile apps may be quite short, meaning churn is likely to be extremely high. Indeed, you probably want to measure on a much shorter period to make any retention-related metrics more meaningful.

11.10Email Metrics

Purpose: To determine the effectiveness of email campaigns.

Despite the popularity of search, email marketing retains a prominent place in the marketing efforts of many firms. Text marketing can follow similar principles. Many of these metrics appear similar to website metrics as they have a similar purpose. The metrics are focused on measuring the level of activity that is generated by the marketer’s actions.

The simplest metric is email open rate, which is the percentage of emails that get opened. Clearly emails that don’t get opened are relatively unlikely to motivate any further action.

Clickthrough Rate is similar to the search metrics and represents the percentage of emails that are clicked on. These might typically bring the consumer through to a website, where they could buy a product.

Email can annoy people, and unsubscribes capture the percentage of subscribers who ask to be removed from a list. All else equal, a list with a high unsubscribe rate is a worse list than one with a low unsubscribe rate. (However, a list on which consumers continue to receive email but aren’t motivated to any action is not especially useful).

Construction

Email Open Rate: The percentage of email delivered that gets opened.

Email Clickthrough Rate: The percentage of email delivered that gets clicked on.

Email Unsubscribe Rate: The percentage of any list of email subscribers that opt out of the list in any given period.

Bounce Rate: The percentage of emails that can’t be delivered. One notable complication is that Bounce Rate for email has a different definition than Bounce Rate for websites. For email, Bounce Rate records the quality of the list rather than any action on the part of the recipient in respect to the email. An older, poorer-quality list is likely to have a higher Bounce Rate as a percentage of recipients will have abandoned their old email addresses. Investigating the data further can help a marketer know more about the source of failure (for example, did the recipient’s server accept the email before bouncing it back, perhaps because the email address has reached its maximum size?).

Cost per Engagement (CPE): A similar metric to the other “cost per” metrics already discussed that measures an essential facet of a campaign. The marketer must define exactly what an engagement is, as it can be essentially whatever the marketer decides, based on the goals of the campaign. A marketer trying to gain email newsletter signups might pay a third party on a Cost per Engagement basis (that is, pay only for signups). Clearly, the third parties must be willing to work closely with marketers to establish the definition of engagement and associated tracking mechanisms.

Data Sources, Complications, and Cautions

The rules on what consumer information can be retained by marketers vary by country. In many parts of the world, a user must consent to receive email before a marketer is allowed to send it. The Direct Marketing Association (thedma.org) and American Marketing Association (www.ama.org) have helpful resources available.

There can be a considerable difference between emails sent and delivered, given abandoned email addresses, bounced emails, and full inboxes. Even emails that are delivered may be filtered away from the recipient’s attention. Users may implement spam and other filtering, which can lead to reduced email response rates that have nothing to do with the effectiveness of the creative message sent. The recipients may simply never see a message, in which case it cannot have an effect even if the message is powerful.

The effect of a campaign can be monitored by tagging URLs in emails. It is then possible to see whether the message drives traffic to the site and which sites have traffic that results in conversions.

For example, one email creative might offer “Buy One, Get One Free,” while the other creative offers “Two for the Price of One.” Sending these emails randomly to the email list allows a marketer to assume that the recipients of each email were similar. Armed with this assumption, the marketer can then determine which creative is more effective, based upon which one is more frequently opened and clicked on.

Email opens and clicks can be used in testing different emails. When using an A/B test, a marketer sends out two types of email. In general, when testing, you should limit the differences between the emails as the differences constitute what is being tested. If you vary many things between the two emails, you need more advanced stats to tease out the effects. And sometimes teasing out the effects is simply impossible. For example, if two changes always occur together, it is impossible to assess the effect of each change independently.

Email marketing relies on the quality of email lists. The quality of lists, for a specific task, can be tested by observing the open and click rates for a message sent to several lists. Even high-quality lists may gain little response if an offer sent is inappropriate to the members of the list.

Further Reading

Google Analytics Academy, analyticsacademy.withgoogle.com/explorer.