Chapter 9 Contents

• The Importance of Measurement 201

• Measuring the Success of Career Development Programs 203

• Measuring Career Development at IBM 208

• New Employee Orientation Measurement Process 210

• Interviews with Participants, Buddies, and Managers 212

• Sales Training Measurement Process 216

In the past, top-level executives and employees throughout the organization were often “home-grown.” We’ve all heard stories about the fellow who started in the mailroom and worked his way up to CEO. As time went on, staying with the same company one’s whole life was no longer seen as the be-all and end-all of career planning. Most companies no longer believe that the majority of their employees will retire with a gold watch after 50 years of faithful service and are looking at ways to measure the impact of factors that drive the retention of high-performance employees.1

In the fast-paced world of high technology, raw people talent separates the winners from the losers. Organizational survival depends on securing and retaining this talent. We’ve established that one effective way of connecting employees to the organization is through a strong career development program.2

In all types and sizes of corporations, career development is a complex and multilevel process that can involve significant expenditures of money, time, and human capital. Because resources are finite and must be allocated among many competing priorities, the following question must always be asked about any career development process, program, or tool: “Is it worth the investment?”

Answering this question as it relates to career development requires methods for measuring and analyzing its effectiveness. Without ways to measure the quality and impact of career development, there is no basis for deciding among the myriad career development options that companies have available to them.

The three main reasons for measuring the effectiveness of career development programs are

• To determine whether career development processes, programs, and tools achieve their objectives

• To decide which approaches are most effective and beneficial and how they can be improved

• To measure the business impact of the program and determine the return on investment

In designing career development processes, programs, and tools, along with determination of their worth, another important question to ask is, “What is the desired objective or outcome?” In other words, what does the company want to achieve or accomplish as a result of this program? Closely related to that is the question, “How will we know whether we have achieved the outcome we want; that is, have we been successful?” This question in particular can be answered through measurement.

Companies must determine the criteria and standards for success and how those criteria will be measured. This helps to determine the degree of success in achieving the objective, in order to know whether the desired outcomes are achieved.

When measurement is done effectively and taken seriously, it can be a major driver for positive change in the organization. In today’s rapidly changing world, companies are only as good as the quality of their data and information. In the sphere of career development, the company that wants to attract and keep the best talent needs to have not only an accurate reading on what its employees are thinking and what they want, but it must also be able to take action quickly in response to needs and wants.

In the following sections, we provide an overview of a career development measurement process, including challenges and opportunities, as well as critical success factors for applying measurement to training and career development. We also share some examples of how IBM has implemented measurements for several learning programs.

Measurement and evaluation are often thought of as final steps in a process, but in fact they should be an integral part of the planning and design of any program right from the beginning. It is important to determine the objectives and measurement guidelines, as well as the process for measuring results at various levels, or else it will be impossible to determine whether or not the program is a success.

From the start, a good measurement system should quantify the effectiveness of the various career development programs, processes and IT tools that support the process. The measurement planning process includes these questions:

• What are the objectives or desired end results?

• What are the criteria that can be measured to indicate whether the objective was achieved?

• How will the data be gathered, analyzed, and reported on an on-going basis, to determine whether the program or process is working, whether objectives are being attained, and whether the program or process is contributing to business results at a level commensurate with the cost?

• Who are the appropriate people to gather the data and do the actual work?

• Are there resources available to collect, analyze, and report data, and then report back to the program owner to make the appropriate improvements?

It is also important that measurement be part of a continuous process for monitoring results along the way. Measurement can be a kind of “temperature taking” at every step of the process to make sure a program is working as designed. This kind of continuous measurement can detect problems early while adjustments can be made easily.

Effective assimilation, higher employee morale, enhanced work “climate,” and improved teamwork are sometimes considered intangible variables. And yet it is often possible to find tangible factors for measuring these variables.

There have been many studies that demonstrate how assimilation of employees and leaders into the organization impacts the bottom line. For example, according to Downey and March,3 in 2000, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu conducted a survey, which found that it takes up to six months to get new employees working reasonably proficiently. It takes 18 months to get them integrated into the culture of an organization, and it takes 24 months before they really know the strategy and the business they have joined. Therefore giving new employees and leaders no training and expecting them to be up and running immediately is unrealistic. In fact, there is only a 50% chance that leaders who take a job at a new company will remain with that company for more than two years. Nearly two years later, these same authors revealed something even more alarming: “More than 70% of newly hired senior executives leave their positions within the first two years.”4

As if these statistics weren’t sobering enough, recently a recruiter who was tracking the careers of 150 senior executives saw that fully 80% had changed employers within two years.5

Sun Microsystems measured the financial aspect of career development on its organization. Sun asked, “What does this mean financially?” It is estimated that the cost to the organization of losing one person is at least 1½ times their annual salary. This includes the cost of recruiting a new person, training costs, and lost productivity. The average salary at Sun during the study period in 2000 was $70,000 per year, which means the cost of attrition per person was about $100,000. Today it is much higher.6

Many organizations today are looking for a relationship between career development practices/initiatives and their impact on core HR and business goals. Questions are being asked, such as: What impact does increased job satisfaction have on business goals? Can we use our career development programs to tie particular initiatives such as increased customer satisfaction or improved teamwork to specific career development interventions? Other focus areas that are sometimes tied to career development that create measurement opportunities for associated impact include the following:

• Higher employee morale

• Higher employee commitment/engagement

• Enhanced work climate

• Higher performance

• Increased productivity

• Increased customer satisfaction

• Increased skills

• Improved teamwork

• Increased revenue

• Lower delivery cost for education

• Lower product/services cost

• Reduced turnover and attrition

From a practical perspective, measuring impact and effectiveness of training and other career development programs is typically done at various levels. These levels measure the effects of the learning at increasing levels of impact.7 Donald Kirkpatrick developed his four-level evaluation model in the late 1950s, and although it has since been adapted and modified by a number of writers, such as Jack Phillips, it remains one of the most well-known and widely used models for career development. The modified five-level Kirkpatrick/Phillips model8 is as follows:

Level 1: Reaction—How did participants react to the program? Focus is on reaction or satisfaction ratings of those who participated, as well as planned actions, if appropriate.

Level 2: Learning—To what extent did participants improve knowledge and skills and change attitudes as a result of the training? Focus is on whether there was a difference between what was learned AFTER event versus BEFORE.

Level 3: Behavior—To what extent did participants change their behavior back in the workplace as a result of the training? Focus is on whether or not people use the learning and apply it to their jobs.

Level 4: Results—What organizational benefits resulted from the training? Focus is on whether there was an increase in productivity, throughput, employee morale, customer satisfaction, or sales. And if there was a decrease in attrition, customer complaints, returns, product development time, or sales cycle.

Level 5: ROI—What is the return on investment? Focus is on whether the return was worth the cost.

Data collection can be considered one of the most important aspects of the measurement process because without valid and reliable data, one cannot draw any conclusions. Data collection for Levels 1 and 2 (participant satisfaction and increased skill) is typically done as an integral part of training or career development activity. Surveys and learning assessments are the most common methods of gathering this data.

Data collection for Levels 3 and 4 (behavioral application on the job and business impact) is done after the training or career development intervention progresses for a period of time or concludes. The methods used include follow-up surveys, interviews, focus groups, and program sessions; program-related assignments; and performance contracting and monitoring.9

Data collection for Level 5 must be isolated from other possible contributions to determine business impact and ROI. The data also needs to be converted to monetary values so that costs and ROI can be calculated and analyzed. Rigorous and sophisticated statistical analysis is required to ensure valid comparisons and conclusions.

Sun Microsystems wanted to find out what would attract people to the organization and keep them there. Career development turned out to be one of the top contributors for attracting and retaining employees, as determined through satisfaction surveys and comments from employees. The company’s challenge in the current fast-paced environment was to “provide a middle ground between defined career paths and ‘figure it out for yourself’ development.”10 Sun, working with the Career Action Center, a Cupertino-based nonprofit organization, created a way to help employees become more career self-reliant while supporting corporate goals and objectives.

Based on employee feedback to Level 1 questionnaires, Sun realized that having a Career Services program was definitely helping workers in their development, but it was less clear how the organization benefited and whether or not the ROI was positive. To this end, Sun launched a study to determine the impact.

By taking the reduced attrition of 1% and applying it to the thousand or so employees who annually took advantage of Career Service offerings, the company saved above $1 million. Career Services also turned out to be a cost-effective means for providing out-placement support to employees leaving the company and contributed about another $100,000 annually to the bottom line (versus using outplacement services). Because the total annual cost of Career Services is about $600k, the ROI was determined to be ($1.1M/600k) × 100, or 183%. The value from Sun’s investment in Career Services is clear, and it would be further increased by taking into account effectiveness.11

While all five levels of measurement are key and each has its place in the overall measurement process, it is costly to measure all five levels for every single career development program or learning activity within the company. Therefore companies must make a conscious decision as to which levels of measurement are really necessary for each program or learning event—and which levels of measurement may not be worth the investment or for which data is not available. In addition, as a program matures, a company could decide that continuing to do multiple levels of measurement is not warranted once the value of the program has been identified. The focus going forward may solely be on continuous improvement of the program to ensure it meets the needs of the audience.

Two essential elements for success are management support for the measurement process and the setting up of a measurement infrastructure right from the beginning. These are important in order to ensure

• The allocation of necessary funding in budgets

• Approval of staff time for planning, design, and implementation of appropriate feedback and measurement processes

• The levels of measurement that are appropriate for the particular program or process, including what data is or is not feasible to capture and measure

• Advocacy for the measurement process in the face of obstacles and possible resistance

• Review of measurement results and support for process improvement

The way in which data is used is also a critical factor in whether measurement programs succeed or fail. Data must be used as a way to support process improvement, not as a way to punish or find fault. Data must be protected from misuse or political manipulation that would advance or hurt particular programs or people. Privacy and confidentiality concerns must be taken seriously and safeguards put in place.

Communication and implementation are critical success factors for any measurement program. All stakeholders must know and understand the purpose and process, as well as their roles and responsibilities, for gathering, reporting, and using data correctly.

Implementation of the measurement program must be rolled out in stages, with carefully monitored pilot programs and feedback processes for identifying and correcting problems from the beginning. The implementation must also be well-coordinated across the organization so that messages are communicated clearly and concisely. A change management process is essential for implementation of a new measurement program to counteract and manage any resistance that naturally occurs when change is introduced.

Before we describe specific examples of career development programs and how they are measured at IBM, it would be helpful to review the Guiding Principles that are the cornerstone for determining the specific measurement strategy for the various components of career development.12 The Guiding Principles are

• Continuous improvement—The purpose of measurement is not simply evaluative, but is to provide on-going information that can be used to improve career programs and processes.

• Collaboration—The measurement process involves input and buy-in from all the stakeholders to get maximum participation and value.

• Consistency—Data is gathered and analyzed in ways that allow for valid comparisons and reliable conclusions.

• Confidentiality—Measurements and the resulting data are designed to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants.

• Objective—Measurement processes need to be designed to avoid bias and personal preference.

• Ease of use—The measurement process should be easy to use for both those completing surveys and for those using the data to make informed decisions.

• Flexibility—The measurement and reporting process should allow for a variety of data sorts and reports to make it usable in a variety of settings.

At a more specific level, IBM uses a modified Kirkpatrick/Phillips model to measure career development. For instance, all classes have at least Level 1 “reaction” measurement; an online survey is sent to the employees immediately after the class concludes to get their input on the class. Many classes also have a “Level 2” or test component at the conclusion of the class, and some also measure “Level 3,” or application on the job. These latter measurements are collected as surveys sent to the students several months after class conclusion to determine how the employees applied what they learned. Many e-learning activities also leverage Level 1 measurements. Levels 1, 2, and 3 measurements are also captured at the learning program level, where a multifaceted learning program is put into place that includes a series of learning activities for a specific audience.

Level 4 or 5 (business impact/ROI) measures are typically done at a learning program level (versus class) for selective programs due to the investment required to do these types of measurements. Often data is not available, or it might not be possible to isolate the impact of the learning activity because of a multifaceted intervention that was implemented, learning being one of various interventions required to solve a business problem.

In the next sections, we describe two major career development programs at IBM and how their effectiveness and impact were measured. We chose to describe new employee orientation and sales training programs because they represent initiatives that are easily identifiable for most readers. These examples represent the higher, more comprehensive levels of measurement described in this chapter.

We also describe aspects of measurements for two other career development programs—an experience-based learning and a global mentoring program. We chose these particular examples because they not only illustrate most of the principles and levels of measurement, but they also have received national and international recognition as examples of best practices. Measurement of these programs demonstrated the impact on the business and also illustrates the use of measurement to continually improve IBM’s offerings.

In Chapter 4, “Selecting the Best Talent and Developing New Employees,” we described IBM’s new employee orientation program as a one-year learning program intended to orient and fully integrate new employees to IBM. These employees may have joined IBM through strategic outsourcing deals, acquisitions, or through traditional hiring approaches, such as college or professional hires. In May 2002, IBM revamped its new employee orientation program. As a result, IBM’s HR organization, along with Productivity Dynamics, Inc., defined a comprehensive evaluation strategy to assess the effectiveness and business impact of this new strategic program. Because this learning program and orientation process was multifaceted and spanned a large period of time (new employee’s first year), it was determined early in the design process that a robust measurement process must be implemented. IBM was able to use various levels of measurement to capture not only student reaction and application on the job, but the business impact of the new employee orientation program. Determining the impact to the business in addition to measuring how employees felt about the program and applied what was learned was key, given the sizable investment the company was now making in designing, developing, and implementing the new employee orientation program.

The newly revised employee orientation program was intended to help new employees have a positive impact on IBM’s business effectiveness. It was tailored both to different types of hires and to various business units and geographies. It continues to be a multifaceted program that consists of e-learning modules, face-to-face classes, coaching by peers, and work-related development activities.

The primary goals of the orientation program include the following:

• To help new employees learn about IBM’s history, culture, and business strategy, so as to identify better with IBM

• To learn to use productivity tools and best practices and to become productive as quickly as possible

• To manage change resulting from joining IBM

• To build productive relationships with their managers and colleagues, and so on

Given the program’s complexity, a two-phase evaluation strategy was designed and implemented during its inception in May, 2002. It was particularly important to measure the program’s effectiveness very early in the tenure of the newly implemented new employee orientation program to ensure it was meeting defined objectives. Such feedback would then be used to continue enhancements to the program as it matured.

The measurement strategy put in place was comprised of two phases that summarized data collection activities during the early implementation in 2003. The following sections describe these various phases.

In the first phase, a “time-series” evaluation design was implemented. This phase consisted of three major steps—data collection, data analysis, and reporting. These three steps were implemented iteratively, as various learning components were utilized by a sample of the first group of participants in the program. The objective of this phase was to evaluate the first iteration of the program’s components by “shadowing” participants through various program activities and making recommendations for improvement. Evaluation data was collected as participants progressed through each phase of the orientation program. This approach allowed the evaluation to be flexible and responsive to the evolving nature of the learning program. It also allowed the evaluation to control for intervening variables, such as business group-specific orientation activities, nonlearning influencers, and so on. The findings and recommendations for continuous improvement were communicated to the program stakeholders and sponsors.

The second stage included a more structured data collection and analysis strategy. This strategy measured iterative implementations of program components after the first implementation of each learning component. The tools and evaluation procedures used during the time-series stage were adapted and implemented in this stage. Given the high number of participants and their wide distribution during the steady state, samples of participants were selected to collect evaluation data.

The actual measurements used during these phases are described next.

Initially, a 1- or 2-day class was held, depending on audience type, at either the 30- or 60-day point post-hire date. It was felt that the class could better serve the employees if they had some orientation on the job before they gathered with other new hires in a classroom setting. A survey was used to assess participants’ reaction to the class and their perception of its learning value and the learning value of other components of the program. The survey was given to all participants upon completion of the class. The questions in the survey covered the following areas:

• Overall reaction to the class

• Learning outcome of the class

• Intention to take action based on what was learned in the class

• Effectiveness of e-learning modules

• General reaction to all components of the program.

The results of the post-class survey were analyzed and reported on a monthly basis.

As part of the process of gathering measurement data, interviews were conducted with participants, buddies, and managers. A random sampling from three categories of interviewees was selected.

A stratified random sample of participants was selected from the first group of new hires (college and professional hires). Variables used for stratification of samples were

• Business Group—Participants represented 27 divisions.

• Starting date at IBM—Participants who joined IBM between May 19 and June 30, 2003.

Multiple interviews were conducted with this sample during the first year of their participation in the program. A subset of program sample participants were contacted through email and were invited to participate in an interview.

From the managers of the participants in Sample 1, a group was selected and invited to participate in a 15-minute telephone interview. Managers in this sample were interviewed several times during the first year of the program continuum.

“Buddies” were assigned to ensure that the new employees connected to others within the business and were available to answer questions. A subset of participants in the sample had assigned buddies. These individuals were invited to participate in a 15-minute interview.

Three interview protocols were developed to collect consistent data from all participants. The following list shows some of the topics that program participants were asked to discuss:

• Timeliness and effectiveness of communications about the program and its components

• Relevance of the program to their work

• Overall perception of the program

• Accessibility, relevance, and learning value of e-learning modules

• Contribution and effectiveness of their buddies

• Support of managers

• Timing and relevance of the class

• Recommendations for continuous improvement of the program and its components

Managers and buddies were asked to describe how program details were communicated to them and how effective that communication was. They were also asked to make observations about how the program was working (especially in comparison to previous new hire programs) and its impact on individual participants. Next they were requested to clarify their personal knowledge of the program and their awareness of their role within it, and finally they were asked to make suggestions for the program’s continuous improvement.

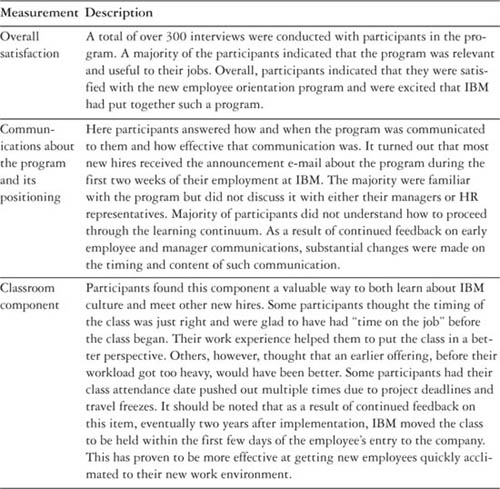

Participants’ feedback and comments concerning the program were summarized and organized as shown in Table 9.1.13

Feedback collected continuously enhanced the program offering, and the results were extremely positive. Managers as well as employees felt their input was directing the “new and improved” program offering.

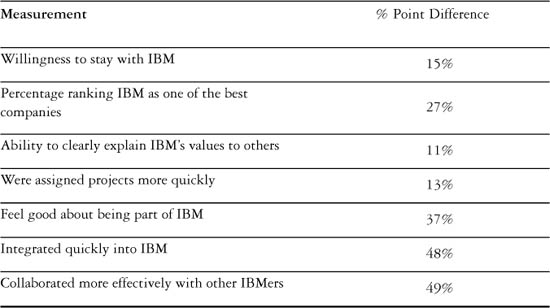

After several years of program implementation, an impact study was conducted, measuring long-term impact on the program. The study included analysis from new employees who participated in the program versus those who did not. The impact data from the 2-year study showed that the attrition rate was nearly twice as high for those who did not attend the program as for those who did and that attendees were over 30% more likely to receive the highest possible ranking on their performance assessment. In addition, attendees had a more positive view of IBM than non-attendees. Comparisons of attendees versus non-attendees on a set of survey items show that, on every item, the percentage of those who agreed or strongly agreed on a 5-point scale were higher for those who attended versus did not attend the program. See Table 9.2 for differences in percentage points between the two groups.

Many of these measurements still exist in the orientation program today. As a result, IBM continues to monitor the new employee orientation program and updates the program as needed. In fact, as we mentioned in Chapter 4, the IBM new employee orientation program is currently going through various changes to reflect current and future new employee needs.

Another example of a robust measurement process that IBM has implemented for a job role-specific training program is IBM’s foundational sales training program for sellers: The Global Sales School. It has a long legacy within IBM and was one of IBM’s earliest training programs. While it has existed in a variety of forms over many years, the changing business and market environment required a new approach to sales training. The prior version was heavily weighted toward classroom time and practice sales calls. It no longer fit with how selling actually happened within IBM, and it was not consistently deployed around the world.

IBM has shifted from primarily a hardware and software business to one that is now over 50% services-oriented. This shift necessitated improving sales skills to create and deliver client value, to communicate industry expertise, to lead clients in innovative approaches to business opportunities, and to manage outsourcing opportunities more effectively. Reinforcing brand equity in the marketplace is based, in large part, on the ability of the sellers to leverage the full breadth and depth of IBM’s resources to create value for its clients. As a result, the Global Sales School underwent a major redesign beginning in mid-2006.

At the beginning of the redesign, the Sales Learning organization analyzed multiple sales performance studies to identify activities that most impact sales performance. Findings were validated through surveys and focus groups with exemplary sellers from all geographies and primary business functions.

The findings concluded that what matters most to new sales hires were14

• Focusing on the client—These activities included prospecting and researching clients and client industries, confirming the client’s compelling reason to act, designing solutions and preparing proposals, presenting solutions or product demonstrations, confirming client benefits and value proposition, and negotiating and closing deals.

• Driving the sale—These activities included identifying leads, exploring and identifying opportunities, creating sales strategies and plans, creating call strategies and plans, making sales calls, developing the client’s perception of IBM’s unique value, gaining support of the key decision leader, and articulating IBM capabilities.

• Navigating IBM—These activities included identifying IBM resources; determining pricing, terms, and conditions; creating, updating, and closing opportunity records; preparing for cadence calls and managing internal communications.

The approach and activities were validated with stakeholders to build a consensus for what the “short” list of the new Global Sales School learning goals should be. A global summit to collaborate on the ambitious redesign was held, representing all regions, business units, and business functions. This summit cleared the path for the new Global Sales School through sharing the differentiating activities within the context of a process that was perceived as fair by all parties.

The six goals of Global Sales School that were subsequently established were

• Accelerate new sellers’ quota attainment.

• Enable new sellers to deliver client value and navigate the breadth of the company through an authentic performance-based and work-based design.

• Create a design that works for new sellers with prior sales experience and those with no prior experience.

• Enable a “guidance team” consisting of a new seller’s manager, mentors, and facilitator for critical sales resources to help that new seller learn more quickly.

• Deliver a blended design for Global Sales School that required sellers to be “out of territory” for a shorter amount of time.

• Deliver Global Sales School consistently across the world to further the transformation into a globally integrated company.

As the design of the enhanced program got underway, the team chose the following areas for measurement and used readily available sources of information to generate the findings:

• Seller productivity—Quota attainment data was reviewed, comparing high performers to those not achieving desired targets, while demographic data was analyzed comparing various sales roles, experience levels, time in territory, and other business considerations.

• Seller performance—Performance records were analyzed for sellers across all geographies.

• Seller perceptions—Level 1 surveys that were received at the end of various sessions were used along with interviews with sellers, facilitators, mentors, and managers.

• Facilitator impact—Facilitator surveys were done at the end of each session and after all coaching and deployment calls. Facilitator team room discussions provided candid feedback on needed changes to modules.

• Delivery numbers—Hiring plan and actual number of sellers who participated in the program were compared and analyzed.

A program such as Global Sales School requires the combined efforts of many people around the world, so adding and demonstrating value was critical. In addition, because sales is so visible to the organization, all business units wanted to know exactly what they will gain. It was important to demonstrate to business unit executives that Global Sales School was being deployed effectively around the world and was producing higher quota attainment from its graduates.

As the deployment of the new design got underway and some time had passed, various measurement studies and analyses revealed the following results from the newly enhanced Global Sales School, based on the six goals for the new program:

- Accelerate new sellers’ quota attainment.

A study of Global Sales School graduates proved that sellers who attend the school achieved higher quota attainment:

• 26% higher for experienced sellers

• 70% higher for new sellers

This significantly impacted the net profitability for both new and experienced sellers. These are spectacular numbers in terms of ROI. Only a few new and experienced sellers are needed to graduate to pay back the design and operating costs of the program.

In addition to the percentages and financial analysis of the quota data, the odds of a Global Sales School graduate being an above-average performer were also examined to ensure that Global Sales School “works” for the majority of sellers. This is similar to medical studies that report on the odds of a given treatment having a positive effect. The study found that

• Experienced sellers graduating from Global Sales School are almost two times more likely to achieve above-average quota attainment by their sixth quarter of selling—as compared to experienced sellers who did not attend Global Sales School.

• New sellers graduating from Global Sales School are over three times more likely to achieve above-average quota attainment by their third quarter of selling—as compared to new sellers who did not attend Global Sales School.

- Enable new sellers to deliver client value and navigate the breadth of the company through an authentic performance-based and work-based design.

The increased quota attainment discussed here also speaks to this point. Additionally, qualitative feedback from sellers found that they mention practice sales calls, navigating the organization, tools/resources, and face-to-face labs as the most valuable aspects of the program. Practice sales calls and face-to-face events have always been popular, but sellers also mention the new elements of the work-based design. They valued Global Sales School teaching them how to operate within the organization.

- Create a design that works for new sellers with prior sales experience and those with no prior experience.

Global Sales School is for sales hires within all business units of the company. This includes

• New sellers who have never held a sales position

• Experienced sellers taking a sales position within the company for the first time

New sellers are enrolled in a 12-week version of Global Sales School, while experienced sellers attend a 6-week version that omits the more basic content.

- Enable a “guidance team” consisting of a new seller’s manager, mentors, and facilitator for critical sales resources to help that new seller learn more quickly.

Besides learning from their own experience, sellers learn from colleagues. Global Sales School leverages a “guidance team” for each seller, which is composed of his or her manager, expert mentors, and facilitator.

Managers receive regular reports on the progress of their sellers in Global Sales School.

Expert mentors (appointed by each seller’s manager) review sellers’ understanding of key sales tools and processes. They are critical because access to experienced colleagues is an accelerator of sales performance. Global Sales School requires expert mentors to review the graduation requirements so they and the sellers spend time sharing information despite other demands on their time.

The same facilitator stays with each seller from the start to the end of Global Sales School and manages the assessment for each seller.

The Global Sales School website is personalized and can automatically distinguish if a visitor is a Global Sales School enrollee, a manager, mentor, or facilitator of a stream of enrollees. Different content and features appear for each type of visitor and provide information about learning plan progress and other pertinent data.

Each seller’s guidance team provides the direction and assistance that sellers need to perform their various deliverables. The sum of these deliverables provides comprehensive training on the “real world” of selling within the organization—enabling sellers to quickly conquer the learning curve and deliver higher revenue faster.

- Deliver a blended design for Global Sales School that required sellers to be “out of territory” for a shorter amount of time.

The new Global Sales School brings efficiencies to the business in terms of effort. It reduces the duration of the training from

• 16 weeks to 12 weeks for new sellers

• 16 weeks to 6 weeks for experienced sellers

- Deliver Global Sales School consistently across the world to further the transformation into a globally integrated company.

Global Sales School trains approximately 4,250 sales hires in over 70 countries annually—half of them new sellers and half experienced sellers. Their improved performance goes straight to the bottom line.

In an interview with Matt Valencius, an executive instrumental in the design and delivery of Global Sales School, he said, “Global Sales School, of course, has terrific ROI numbers. But, more than that, the process to demonstrate value every step of the way is what makes the effort stand out. We simply needed the measurements of incremental value to get through each stage of the process. And, these various measurements build upon each other until the evidence is just overwhelming that Global Sales School increases the productivity of new sales hires.”15

Many of the best practices Sales Learning demonstrated with the redesign of Global Sales School are reusable inside and outside of IBM:16

• Be clear on what value the new learning program is intended to bring to the business. Clarity on business alignment makes it easier to form an effective partnership with stakeholders and to remove distractions. The motivation for the redesign of Global Sales School was to accelerate the performance of new sales hires so that they could help the business grow faster. This served as a strong reason for a performance-based and work-based design and helped prevent the design from evolving into a disjointed collection of disparate content important to different stakeholders.

• Conduct a performance differentiation analysis before beginning the design to learn what differentiates top from typical performers. This will focus the design on a finite set of high-value activities. “Accelerated performance” was not sufficient information to build a program around. We needed to know what activities were correlated with high performance and differentiated top from typical sellers. This list also helped us keep the design focus on a finite number of activities—again avoiding the problem of every stakeholder promoting their favorite topic. A performance differentiation analysis can be used to create a solid foundation for any planned learning offering.

• Determine what measurements will be reported back to the business so that expectations can be set and the design can be optimized to produce them. Obtaining a measurable increase in sales quotas was always the main goal for Global Sales School—solid proof to the business of the value the program delivered. Knowing that this was the goal early on enabled us to design the tracking systems we would need to determine “who did what” and to have enough time to work with all the different parts of the business responsible for financial data. It also enabled us to set expectations with stakeholders so that they would “give us space” to create the design and measure the results. We were following a planned measurement strategy rather than reacting to ad-hoc demands for information.

• Make the design performance- and work-based. Global Sales School has sellers build skills in the very same tasks they will need to perform in their jobs. This saves everyone time. The design of Global Sales School is also careful to assess these authentic work deliverables rather than knowledge of theory or effort. Focusing learning on authentic “ends” rather than “means” drives sellers to concentrate on effective execution—exactly what we want them to do “on the job.”

• Leverage and reuse technology and applications as much as possible. Any custom technologies created for the program should be designed with an eye on reusing them on future programs. Global Sales School can be run efficiently due to the many technologies we have created over the years to effectively manage blended learning designs. The innovations and enhancements created for Global Sales School will be reused in future learning programs. Strategic reuse is critical for learning to deliver the innovation and value to the business on budgets that support the growth targets of the organization.

• Design and development teams should work closely together to ensure that the program launch goes smoothly. Global Sales School had multiple interlocking teams to ensure that the design progressed from analysis through measurement without important work being “dropped” or continuity lost in the transition from one team to another. Clear distinctions between design and deployment must be drawn for work to be done efficiently. Team members must also be willing to play multiple roles to keep the project moving quickly and effectively toward a successful launch.

In the past few years, several other career development programs were implemented that have proven to have positive impact on employees. While the programs did not warrant the extent of measurement that the new employee orientation program or Global Sales School did, results have been very favorable and provide an avenue for program improvement.

Listed in this section are examples of how IBM measures the success of its experience-based learning initiatives.

In Chapter 8, “Linking Collaborative Learning Activities to Development Plans,” we described a variety of experiential learning activities that are part of a formal program IBM implemented in 2006. This experienced-based learning program was implemented as a solution to provide a systematic approach for employees to

• Acquire new or enhance current skills by participating in global experiential developmental opportunities such as stretch assignments, cross-unit projects, job shadowing activities, and so on.

• Expand their knowledge and professional development in ways other than traditional classroom and e-learning training and without limitations of country borders.

• Use a “learning opportunity bank” to apply for the various experiential developmental opportunities available on a global basis.

The program connected employees to global business opportunities, enabling them to find the best alternatives for personal career growth, skill and expertise development, and created an optimal experiential solution based on individual needs. From the inception of this initiative, the goal was to ensure that experienced-based learning opportunities offered critical business value and that it was aligned with not only HR learning strategies, but also with the company’s business unit as well as overall strategies. After demonstrating that opportunities could be customized to accommodate flexibility in time for employee participation, business units were receptive to making it part of their career development offerings and built on the successes of the program.

User feedback was monitored to gain insights into participation in the program, effectiveness of the program, application of learning, business results, employee satisfaction, and improvements to the program.

A strategy was designed to

• Determine readiness and awareness of the program, its perceived value by employees and managers, and how well it was being utilized by employees.

• Ascertain the business impact of the program, including employee satisfaction with the learning activities and application of learning on the job.

• Establish its impact on employee morale, retention, and performance.

• Evaluate financial impact, using criteria such as cost saving/avoidance, revenue growth, and increase in innovative solutions.

• Make recommendations for continuous improvement of the initiative.

Information is reported to senior management on a periodic basis and includes “hits” to the program-specific website, how many new participants the program has been deployed to, number of posted and available opportunities in the learning opportunity bank, and number of filled postings—or matches of opportunity to employee need. Feedback forms are sent 30 days following the completion of the activity to determine satisfaction levels and application to the job (Levels 1 and 3 measurements).

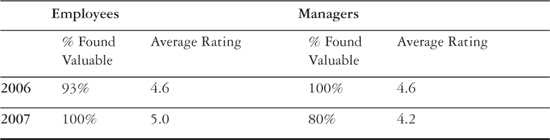

An example of the initial business impact of the program, shown in Table 9.3, is found in the results of an application and impact study conducted in 2Q 2007.

Survey and interview data were collected and analyzed for participants, including a representation of 35% managers and 65% nonmanagers. The findings indicated all interviewees (100%) viewed the program as a worthwhile investment for the company and should continue. Furthermore, when participants were asked to rate the value of the program to employee career development at the company, they stated that the program added value to both employees and the organization in the following ways:

• Skill development

• Networking

• “Larger picture” of the company

• Employee motivation

• Safe exploration of new roles

• Employee retention

• Employee productivity

In Chapter 8, we described IBM’s mentoring program. In 2004, IBM “re-invented” its mentoring program, a blended approach to mentoring that provides diverse and just-in-time solutions that leverage multiple forms of technology and learning tools. The IBM mentoring program is designed to provide another avenue to help employees achieve their career goals, assist employees in the development of a network to stay connected in a remote environment, and to develop employees by providing an avenue for skills and knowledge growth.

The program’s multimedia strategy allows mentoring to take place across different geographies, time zones, and cultures by selecting from a cafeteria of blended learning methods that best support their specific needs.

In its re-invented form, the global mentoring program includes the following elements:

• A global corporate online employee directory was updated in late 2008 to enable employees to register as mentors or to find mentors anywhere across IBM’s global enterprise.

• A “Dear Mentor” electronic forum was developed so employees across the globe could ask questions and receive responses from volunteer mentors within 24 hours.

• Centralized, web-based tools were developed to provide a one-stop mentoring guidance repository.

• Virtual technology such as Second Life and Metaverse was used to connect employees across geographies.

• Lunch and learn sessions, pod casts, webcasts, Wikis, and teleconferences were made available and accessible.

The company developed, implemented, and evaluated a blended learning approach to make mentoring pervasive in IBM, to fit the learning needs of the diverse populations in IBM, and to respond to changes in the global marketplace.

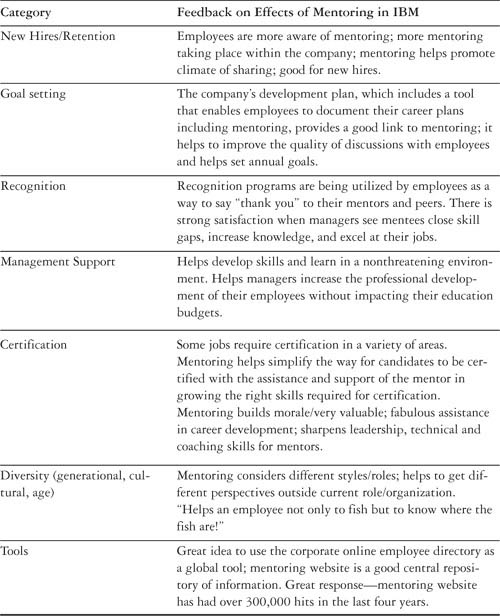

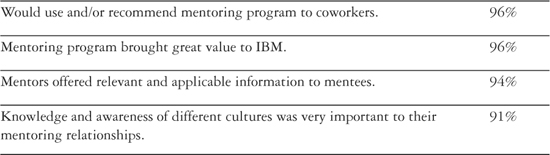

A high-level summary of results from North American focus groups conducted in 2008 showed positive comments and trends in various categories, as is reflected in Table 9.4.

Cross-geographic mentoring programs matched mentors from the United States with mentees from emerging countries, to focus on areas of development including

• Career progression and development

• Viewing the career path from different perspectives

• Patent development

• Personnel management

• Challenges faced working in different time zones

• Work/life balance

• Industry knowledge and research capabilities

• Navigating the company

• Developing global leadership skills and global business acumen

While several cross-geography mentoring programs were run in 2008, the following is one example of the program’s effectiveness. In August 2008, employees in China were surveyed about the impact of cross-geographical mentoring by U.S.-based employees. The results are summarized in Table 9.5.

The collective impact of the combined career development initiatives are measured on a regular basis. A comprehensive measurement and evaluation plan has been put in place, where stakeholders are involved in setting standards and determining the indicators of success for the entire array of offerings. Employees as well as managers are asked what they would view as critical success factors for career development. A statistically representative sampling of managers and employee focus groups generated the criteria for success that allowed IBM to create a management system and culture that supports skill development and growth and gives employees the opportunity to improve skills and expertise.

Measurements are put into place at the learning activity and program level; however, how does a company evaluate the collective impact of all the various programs and activities? While each event or activity might be an isolated incident, often it’s the collection of these items that provide the real value to employees—and the company.

One way IBM measures the overall impact of its collective career development programs is by using an employee survey that is conducted several times a year across random samples of the entire workforce. The purpose of the survey extends way beyond just measuring the impact of career development; it captures data related to job satisfaction, productivity, and other related areas. One of the questions that HR uses to gauge the impact of its career development efforts is one focused on career opportunities. This question is as follows: “I am given a real opportunity to improve my skills at IBM.” Between 2003 and the first quarter of 2009, there was a 7-point gain in the response to this career-related question. This shows a significant increase in employee satisfaction in their perception of being able to improve their skills at IBM. While many factors could have contributed to the increase (or decrease) in responses to the employee survey questions, various new or re-vamped career development programs, processes, and tools in IBM were launched between 2003 and the end of 2008 that collectively may have had an impact on employees’ perceptions of this career-related question.

Perhaps you thought career development was a rather uncomplicated, straightforward process. People get a job, they do it, become proficient at it, and sometimes a promotion or new job opportunity comes along. However, after reading this book, you should be convinced that career development is more than just the job. It’s about employees seeking their passions, finding meaning in their work, planning the best way to develop themselves, and finding the right learning activities to develop expertise. It’s also about enabling the company to achieve organizational goals and ultimately provide value to the client.

The past eight chapters of this book have been dedicated to exploring the components of an agile career development process and providing examples of best practices that have proven to be instrumental in creating an environment for employees to become engaged and meet their career milestones. It is important to view all the various components as a holistic system, whereby the output of one part of the process provides an input to the next part of the process. The career development journey begins from the moment the employee interviews for the job. Companies need to be mindful of setting employee expectations from the beginning so that employees have a view of the opportunities the company could offer them—and so that the company hires the right individuals who can close whatever skill gaps exist.

Once employees enter the company, they need to feel welcomed, and they need a plan for getting quickly immersed in the work they were hired to do. An appropriate on-boarding process and new employee orientation program can help employees get through any initial hurdles they may encounter to becoming productive in a timely fashion. Additionally, introducing them to the career development process early in their tenure helps them to visualize the career possibilities so they can work with their managers on laying out plans for achieving career goals.

Companies need to consider how they are going to determine the types of job roles needed; the expertise required to fulfill those roles; and then how employees can gain the appropriate experiences and engage in various learning activities to progress in their careers. Instrumental to this is the creation of some form of common language or “taxonomy” for how jobs and associated skills are defined, how skills can be assessed to determine gaps, and how employees can identify the right learning activities and experiences needed to fulfill those roles. And learning activities can take many different forms, from the more traditional, such as classroom training or e-learning, to the more experiential, such as mentoring, job shadowing, stretch assignments, and job rotations. Companies need to provide a way to identify such activities—and create the environment that enables employees to engage in them.

It is also important for companies to create a career framework that gives employees a view of how to succeed in one or more career paths to gain depth and breadth of the expertise needed to succeed. The framework should be flexible enough to allow employees to move vertically along one career path, gaining different experiences in related job roles that build deep levels of expertise. Also important is to allow employees, over the course of several career paths, to grow a variety of skills and capabilities, gain experience, and become very versatile in several major areas. Building this type of individual capability helps to grow organizational capability that ensures companies have a workforce with the right expertise to provide the right value to clients.

All of these various aspects of a career development process need to come together for employees through a career development plan. The plan is a way for employees to think about what learning activities and experiences might be needed for them to become more skilled in their current roles or what their next career moves might be. Equally important is manager engagement in the discussion with employees on their development. Managers are the critical link of the support system that employees need to succeed. Managers have a responsibility to help their employees plan their development, as well as creating the right environment so they can execute their plans.

Lastly, companies must put in place the right measurement systems that continually gather feedback from employees, managers, executives, and clients to ensure that the career development process and associated programs are appropriate. At the time of this writing, continued changes in the global economy and rising unemployment, coupled with continued generational difference and the rapid changes in the way employees learn and gain knowledge, may have a profound impact on how career development is viewed in the future. Companies need to continually assess, measure, and change their career processes, programs, and tools to reflect the needs of their employees and their organizations.

The lessons provided in this book can guide companies on establishing the basics of career development, and if implemented, can help companies weather changes to make certain that employees have the appropriate expertise needed to ensure the future success of the company.

Endnotes

1Bing, Diana, and Dave Gettles. “Business Coaching and Executive Onboarding” presentation, July 2002.

2Phillips, Jack, J., editor. In Action: Performance and Analysis Consulting (Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development, 2000), pp. 53–66.

3Downey, Diane and Tom March. “Comfortable Fit: Assimilating New Leaders,” Executive Talent, Summer 2000.

4Downey, Diane, Tom March, and Adena Berkman. Assimilating New Leaders: The Key to Executive Retention (New York: AMACOM, 2001).

5Cappelli, Peter, “A Market-Driven Approach to Retaining Talent,” Harvard Business Review (Jan/Feb 2000): pp. 103–111.

6Elsdon, Ron and Seema Iyer. “Measuring the Impact of Career Development on an Organization,” Sun Microsystems Inc., 2000, p. 11.

7Kirkpatrick, Donald L. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels, 2nd Edition (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1998).

8Phillips, Jack J. and Ron Drew Stone. How To Measure Training Results: A Practical Guide to Tracking the Six Key Indicators (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002) p. 10.

9“Productivity Dynamics,” Your IBM Learning Continuum (September 2003): p. 122.

10Elsdon, Ron and Seema Iyer. “Measuring the Impact of Career Development on an Organization,” Sun Microsystems Inc., 2000, p. 18.

11Ibid.

12Weldon, Laverne. Adapted from IBM Document on Measurement Philosophy, 2007.

13“Productivity Dynamics,” Your IBM Learning Continuum (September 2003).

14Valencius, Matt. Adapted from IBM Document, Global Sales School, 2009.

15Interview with Matt Valencius, Executive with the Center for Advanced Learning, IBM, April 6, 2009.

16Ibid.