Chapter 4. Discovering and Using Keywords to Attract Your Target Audience

As we indicated in Chapter 3, the search-first writing methodology begins with keyword research, after which you write pages to attract your target audience and address their needs with relevant content. The two inputs to your writing plan are a description of the target audience and a set of keywords that the target audience is likely to use. Armed with this information, writing Web content that is optimized for search engines—particularly Google—is a fairly simple matter of making sure Google’s crawler can find the keywords in strategic places on your pages. This chapter covers those three tactics, along with some necessary background information on the linguistics of search engines:

• Defining your target audience

• Linguistic considerations for keywords

• Discovering the keywords related to your topic that the audience most often uses

• Developing Web content with those keywords in strategic places on your pages

Defining the Target Audience

Defining your target audience is another aspect of Web writing that does not resemble many print contexts. In public relations, the writer develops a list of press analysts, editors, and publishers and writes press releases for them. In sales, the writer typically has a lot of information about the client for whom the sales proposal is written. Grant writers have details about the reviewers for their grant proposals before they write.

Those are just a few of the cases in the print medium in which the audience is well known. There are also many more cases in which you really know very little about your audience in print, except perhaps that they are interested in what you write. If they are not interested in what you write, they will stop reading. But this is not very helpful in crafting messages that appeal to their needs. When we form a picture of our audience, we strive to understand things such as their prior knowledge, common experiences, shared beliefs, and shared assumptions, so that we can use these traits to engage the reader, and to narrow our focus to what the reader needs. In short, given what we know about our audience, we want to maximize relevance for them. A corollary of this is that we also want to minimize what is irrelevant to the reader. Irrelevant content acts as friction and distracts readers from getting what they need.

Whether you know a lot or a little about your target audience in print, your audience analysis vastly differs from Web audience analysis. In print, you discover who reads the publication for which you are writing and try to appeal to their common traits. Lacking such knowledge, you engage them with compelling storytelling techniques, compelling them to do things your way. But on the Web, you don’t simply discover traits about your target audience. You define your target audience by some common traits and seek to attract only people who have those traits to your site. Print is passive; the Web is active. When you are confident that you are attracting your target audience to your pages, you are free to address them and use their defined traits as the common ground that you need to achieve mutual understanding.

Web audience analysis is less about discovering common audience traits than about defining them. In passive media such as print, you discover common audience traits (such as subscribing to a vertical journal) and use these traits to help you make assumptions about their common knowledge. These assumptions help you focus on what they need, rather than writing for the least common denominator. But in active media such as the Web, you can’t make these assumptions as readily because of the diversity of the audience. So you are forced to define the audience that you want to attract and write in ways that will tend to attract that audience through search.

When you define audience traits, you simply identify the interests of your target audience. For example, suppose you have a writing and editing service and want to attract clients who are interested in this kind of offering. If you narrow your focus on this simple trait, your audience might be highly diverse, but they have one trait in common—they need writing and editing services. Unlike with print, the more you narrow your definition of your target, the more effective your Web writing will be. If you try to associate the main trait you seek with a set of likely complementary traits, you risk writing irrelevant content for those who do not share those complementary traits.

For the moment, let’s assume that the only thing you know about your audience is that they came to your site from Google using keywords that you coded into your pages. That doesn’t seem like a lot of information to go on. However, as you follow our information path through this book, you will find that it is more than you might think. It is just a simplifying assumption. We will go into depth about what you can know about your audience, and how to gain this knowledge in Chapter 5. But if you only know that your users came to your site from Google using certain keyword phrases, you know that most content topics related to those keywords will likely be relevant. We’ll explore this here by explaining how to design information that will be maximally relevant for users who come to your pages from Google.

Some Linguistic Considerations Related to Keywords

Until now, we have talked about the keywords that your target audience enters into search fields, without talking about what keywords are and how they work so that Google can identify relevant content. Strictly speaking, keywords are strings of characters that people enter into search fields. Actually, it is a bit of a misnomer to call them “keywords,” because many users enter phrases or word combinations into search fields, to try to zero in on the most relevant content. The shorter the string of characters entered, the less likely it is that the search will return relevant results. On the other hand, as we have mentioned before, sophisticated search users enter long-tail keywords because the longer and more complex the search string, the more likely the result will be relevant.

Google indexes Web content by keywords. When a user enters a keyword string into a search field, Google uses its algorithm to determine the most relevant content in its index for the search term. We will delve into further aspects of the Google algorithm later in this chapter, but for now, think of it as a matching algorithm. If a user enters a string that exactly matches the keywords that Google associates with a piece of content in its index, there’s a good chance that piece of content will appear in the first few pages of results. If there are no exact matches, Google tries to match parts and pieces of a keyword string to the content in its index. This means that unless a query is made using the advanced search function, Google’s algorithm will associate any of the words in a keyword string to find the best matches, in any combination.

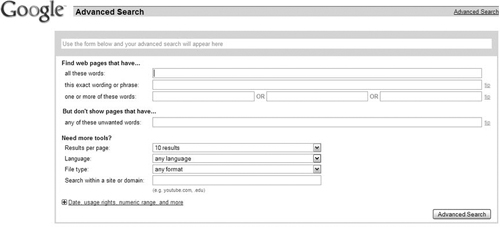

Users of Google’s advanced search function can use Boolean specifications to designate not only the words in a keyword phrase, but also the logic of their combination (Figure 4.1). For example, Google’s Advanced Search screen has a field with “all these words” as its label. If a user enters ibm developer soa in that field, Google will only find pages that contain all those words. Users can also exclude content by putting words to exclude in the appropriate field. Another trick for queries is to use quotation marks to tell Google to only show content with that exact phrase; Entering "ibm soa" (including the quote marks) will only return phrases that contain that particular phrase.

Figure 4.1. The Google Advanced Search Application.

(Source: /www.google.com/advanced_search?hl=en)

If users don’t get the desired results from a keyword string, they often go back and modify the string. For example, a novice user might enter the word blue in a search field. For such a vague search term, Google might return a staggeringly huge number of results, none of which would be useful. So, the user might go back and enter Big Blue, indicating that she’s not just interested in the color, but in one of its many associations, this time with IBM. And she could further refine her keyword string to narrow her search through trial and error. Users often find content this way: They start with vague, generic terms and gradually narrow their search down by adding modifiers.

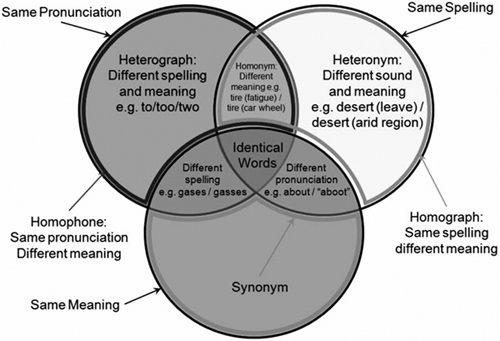

We assume that you have some experience using search engines. In particular, you might have had the experience of trying to find content related to a keyword and finding the results completely different than you anticipated. Typically, this happens when Google has a hard time interpreting your search query. Why? Well, natural language is extremely complex—too complex for computers to divine the meaning of a few words taken out of context (see Figure 4.2). In particular, a lot of words have multiple literal meanings, called homonyms. Read the dictionary to see several definitions for the same word, and you can begin to understand the challenge. Another common set of linguistic complexity is called homographs: words that share the same spelling but are pronounced differently. For example, the words lead (as in leadership) and lead (as in pencil lead) look identical to Google unless they are put in the context of their parts of speech, prefixes or suffixes. Many more variations on homographs can be found in the English language. (See the sidebar for a more complete discussion of the variations.) We won’t delve too deeply into the complexity here. Suffice it to say that the most effective keywords have some of this context built in (with prefixes, suffixes, and use of various parts of speech).

Figure 4.2. A graph of linguistic complexities related to keywords.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homonyms)

It’s hard to take a few words in a search string and understand what the searcher meant by them. And once the computer makes an educated guess, it is even harder to find the most relevant content for that meaning. The same keyword with the same meaning is typically highly relevant only to a subset of the population, and totally irrelevant to the rest. Google is a marvel of human ingenuity because it does a pretty good job not only of divining the meaning of a search query, but of providing relevant search results. But not all of that is linguistic. About half of Google’s algorithm deals with the popularity or link equity of pages in its index. This helps Google determine the pages most likely to be relevant to the searcher. We will discuss PageRank in Chapter 7. For now, it’s enough to know that Google doesn’t simply rely on the semantics (the linguistics of meaning) of search strings, but also builds a context around the pages in its index by considering such extra-linguistic features as links.

Discovering Keywords Used by Your Target Audience

The central aspect of search-first writing is to connect with your target audience by crafting Web experiences using what you know about Google. The first step in this process is called keyword discovery or keyword research. Many Web publishers assume that they should just write what they want to communicate and let the search engines naturally find their content. This works if the vocabulary you use happens to coincide with the vocabulary your target audience uses to find pages of interest in Google. However, in our experience, creating search-optimized content by accident rarely happens. Especially when writing in marketing settings, writers often fail to realize that their company’s specific vocabulary pervades their writing. This means that the writers are using too much specialized, branded language. This neglects search optimization or leaves it to chance, which produces very poor results. Don’t leave your search optimization to chance this way.

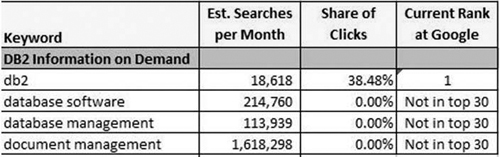

By using keyword research, you can gain some measure of control over search optimization by ensuring that the vocabulary you use on your pages is the same as that of your target audience. Keyword research tells you how many people searched on a particular term in a given month. This is not the only information you need, but it is a starting point. If you don’t do keyword research, you can own the top position in Google for a term that very few people search on but get very little traffic to your pages as a result. If you use a coined or branded term, chances are that people who find your page from Google will find it relevant to them. That might be good enough for certain circumstances, but it is not good enough for most. Keyword research can help you discover the terms that are both relevant to your target audience and get a relatively high volume of traffic. That is the goal of keyword research.

On the other end of the scale, you can rank well for words that lots of users search on and get lots of traffic to your pages as a result. But if most of those users bounce off your pages, indicating that they find the content irrelevant, you will need to find terms that are more relevant to your target audience. It is better to have decent levels of traffic with low bounce rates than high levels of traffic with a lot of bounce. Each time that users bounce off your page, you leave a negative impression in their minds, and you hurt your ranking in Google. On the other hand, each user who comes to your page and is drawn to engage with your content by clicking your links will have a positive experience. Again, the goal is to combine relatively high traffic with relatively low bounce rates, because ultimately, low bounce rates tend to lead to high engagement rates. Engagement is the best way to measure the relevance of your content for your target audience. (We discuss how to measure bounce and engagement in Chapter 9).

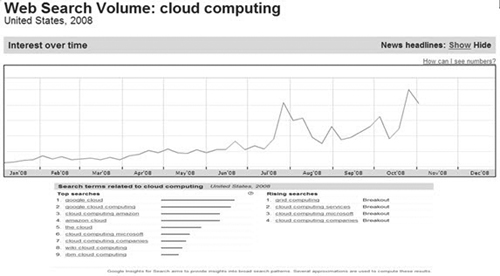

You can’t do your keyword research just once, though. If you find high bounce rates, you will need to revisit your content, choose new keywords and republish—and do more keyboard research. Page-level research and keyword research are iterative processes. From your initial keyword research, you can make a good educated guess as to which terms your target audience is most likely to use when searching for content. But this initial guess often misses the mark. Then, you need to do deeper keyword research and craft content that better targets your audience. So, keyword research should be a central part of your everyday Web operations. In particular, it should always precede the writing of each piece of your Web content. It is better to write with the keywords that your target audience uses than to retrofit content with keywords after the fact, keywords which may not perfectly match the content you’ve created. The good news is that if your initial research misses the mark, the power of the Web allows you to make changes and republish relatively easily. Take advantage of that power.

So you need to do your keyword research before writing. How do you do this? Conducting keyword research is a matter of figuring out what terms related to your topic are most often searched on and choosing the words or phrases from that list that you think your audience is most likely to use. As we indicated above, it is an iterative process—you make an educated guess and test your success, prepared to make adjustments to tune the relevance of your pages for your target audience.

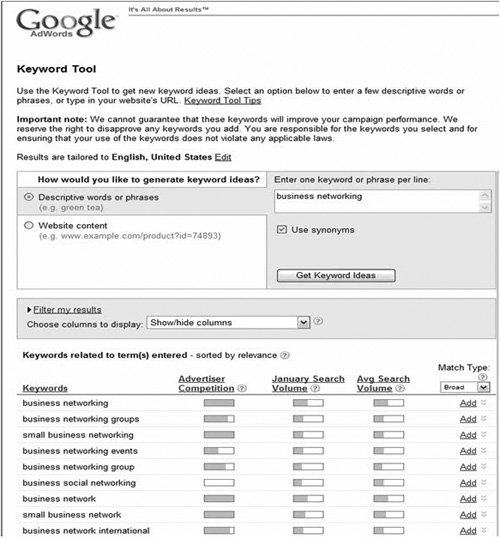

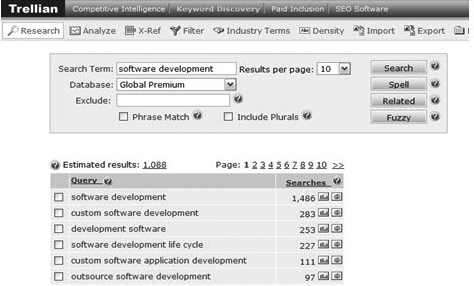

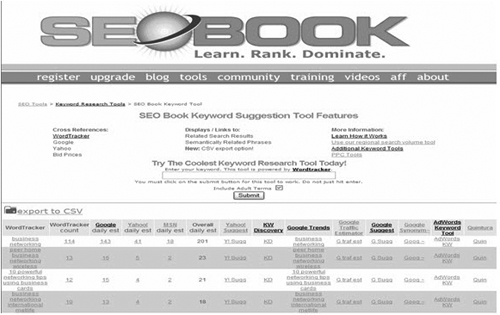

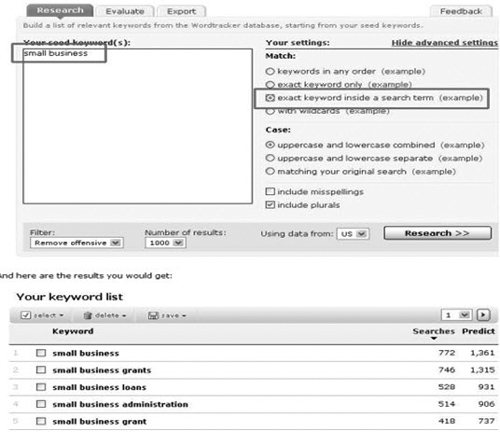

Figuring out which terms are most often searched on is a matter of using tools such as Google AdWords to test possible words and phrases. There are dozens of tools (see the sidebar for a more complete list) for finding the most often-searched-on terms, with a variety of cost structures and feature sets, including the Keyword Discovery Tool (www.keyworddiscovery.com/start.html) or Aaron Wall’s Free Keyword List Generator (http://tools.seobook.com/keyword-list/) to discover the demand for a keyword. Demand is a function of the number of users who search on a term in a given time frame, typically a month.

In addition to demand, you also need to measure competition for your keywords. Competition can be measured in several ways. But technically, it’s the search strength of the pages that rank on Google’s top page for your chosen keywords. The best way to learn this is simply by searching on the words and looking into the pages that rank well in Google. How well optimized are these pages? How interwoven are they in the topic or field surrounding them? A keyword that has lots of high-powered competition might not be your best choice. But some words are central to your mission, so you absolutely have to own them. Smarter Planet is such a keyword for IBM. So you do what it takes to rank well for those words.

A quick-and-dirty way to test the words that you think might be popular is simply by typing them into Google. As shown in Figure 4.4, under Google’s default setting of “Provide query suggestions in the search box,” you’ll see various incremental possible matches for your search string, with the total number of “hits,” while you type in your entries. This only gives you a rough estimate of the competition for the keywords. To get the information you need to determine competition, you’ll have to use the tools that measure competition, such as Covario. Because we try to focus on free tools in this book, we will not delve into a description of Covario. Feel free to check it out on your own (www.covario.com/). Wordtracker (www.wordtracker.com/) has a free tool to help you measure keyword competition.

Figure 4.4. A quick-and-dirty keyword discovery tool to get a rough estimate of keyword competition from the Google search page. We recommend using Wordtracker or a similar tool to validate your initial keyword competition data.

(Source: www.google.com)

When we consult with content teams about SEO with regard to keyword research, our clients sometimes think that keyword research tools are 100% accurate. This is a misconception, because we generally see varying results when using different tools for the same keyword. The results for each tool are based on a different sample searches and different sources. Some tools, like Wordtracker, use specific search engines. No tool can capture 100% of all Internet searches for a given keyword.

For example, the popular free Google AdWords Keyword Research tool (Figure 4.13) is really a pay-per-click (PPC) tool that also counts any clicks on an impression as an actual search. When Google provides approximate numbers, it draws from a variety of sources, not just the number of searches on a term in a given month. It also includes clicks on impressions, parked domain advertisements (domains registered for possible future use or to prevent competitive purchase) and searches from partner engines as well. All of these, along with the addition of robot searches, can inflate the numbers.

Figure 4.13. A Google AdWords interface.

(Source: Google)

![]()

So with these Google results, if you divide the approximate average search volume of 14,800 per month by 30 (the number of days in month) you get around 493 searches per day. The conundrum is that you still cannot determine how many searches came from particular actions, such as clicks on impressions. What Google is measuring is more about users’ interest in the keyword (in this case, server virtualization) than about actual searches. The search volume numbers should be used to compare various keywords.

In general, keyword research tools provide value by showing searcher interest, competition for keywords, semantically related alternatives, keyword comparisons, and seed words to use in social media for further long-tail research. We advise that you use them in conjunction with each other, because no one tool provides a complete picture of the demand, competition, and relevance for your content of a particular keyword.

Getting Started with Keyword Research

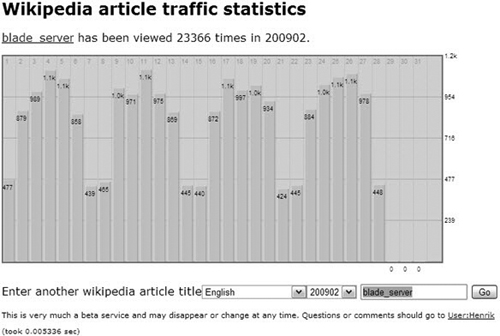

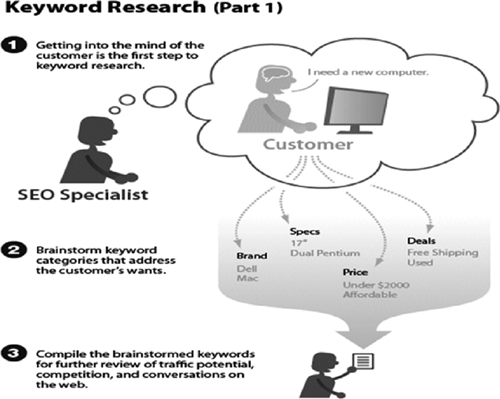

No matter what tools you use, you need to have an idea about the keywords to test out in the first place. This is a complex process involving several steps. The first step for keyword discovery is to obtain a list of so-called seed words. These are the usual descriptive words, also known as themes, topics, core terms, or keyword clouds. This process involves brainstorming about the main words that your target audience associates with a topic. The cloud should contain all the grammatical variations of the words, as well as all synonyms. Seed words are typically root words, from which it is relatively easy to add prefixes, suffixes, and contextual combinations of the words.

It’s important to start this process with the most generic words you can think of and gradually narrow the list down until you have a manageable list to test in your tool. For example, when an IBM content team needed a list of keywords for a set of Web pages promoting environmentally friendly technologies, the team joked that it needed to start the process with the terms earth, air, fire and water—the most elementary terms in Aristotle’s lexicon. Though it was a joke, it demonstrated just how broad the initial pass of possible terms and their relations needed to be. Starting with a small, broad list ensures that you won’t miss any terms that might particularly connect with your target audience. You can always go back and narrow your keyword list down, but it is really hard to go back and include a whole cloud of related terms after the fact.

If it seems daunting to sit down with a content team in front of a white board and write down the most elementary words, with all their linguistic variations, the keyword tools can help. Many of them can generate all possible grammatical variations of terms, and their synonyms, from a small list. Of course, they ultimately help you determine how many users search on the keywords. They also provide insights on which terms are more competitive and which terms drive more qualified visitors. See the sidebar for a description of the four to seven tools we recommend, in order. Suffice it to say that the goal is to have a list of related keywords that will attract your targeted audience through Google. When you have your list of keywords, you then try to write one page of content for each keyword in your Web architecture. We discuss these architectural considerations in Chapter 6.

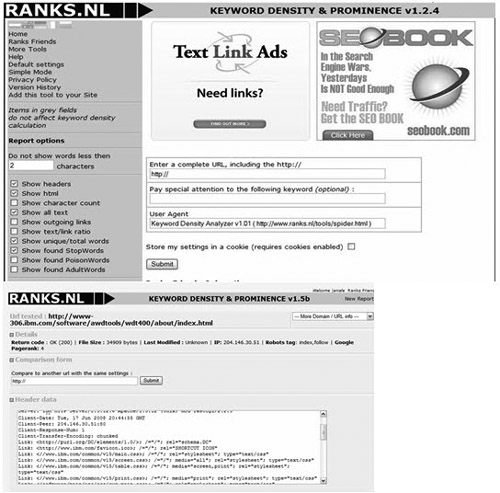

As we said, the ideal state is to have all your keywords before you write, but that is not always possible. Many search optimization efforts happen after the fact. In a sense, it is easier to do keyword research after the fact, though it might not be as effective. The reason is that there are all kinds of tools that enable you to scan your existing content for keyword frequency and develop a list of seed words from that list. Tools such as the Word Frequency Calculator (www.darylkinsman.ca/tools/wordfreq.shtml) enable you to cut and paste your existing copy into a box and generate a report on the words that appear most often. You can also exclude stop words (articles and logical connectors) or focus just on elements such as nouns or verbs. If a word appears often in an existing piece of content, it’s a candidate to add to your keyword cloud.

Of course, word frequency is not the only consideration. For example, you might have a legal disclaimer on the bottom of every page that contains words completely irrelevant to the content on a page, yet a frequency counter might list them as the most frequently used words on it. Tools can help, but it typically takes human intelligence, especially from the writers and editors of the content, to develop a list of seed words from a set of existing content.

Once you have the cloud of words you want to test, you can run it through the keyword tools. Typically, you’ll discover that the keywords you chose when you first published your content are not often searched on (as was the case in the case study in the sidebar). The keyword tools will generate reports that show which related words or phrases were most often searched on. Then again, you will need human intelligence to determine which words best target the desired audience while generating more traffic from search than the original words. Often, several very similar words will have similar search numbers. In that case, you make your best guess and test after the fact. It is often more important to get the content up and connect with your target audience right away than to deliberate to perfectly target your audience, and thus delay your publishing efforts. As we say at IBM, search optimization is like washing your hair: Lather, rinse, repeat.

Optimizing Web Pages with Your Keywords

Google sends crawlers or spiders through the Web to find content that might be relevant to its users. These are simply programs that scan pages and return information about pages back to Google. Based on this information, Google then places the pages into its index. The index listing for a piece of content contains the information about the page that the crawler gathered, which helps the algorithm rank the page against others on the Web for the same keywords.

Optimizing pages for a given keyword is about providing the information the Google crawler is looking for in an efficient way. If the crawler has to work hard to find the information it’s seeking, it might not capture the information you want it to, and the content that ends up in Google will have an incomplete index entry. For example, if a page includes a Flash experience or a lot of JavaScript, the crawler might not capture all its content, and the page will not rank well. (For this reason, we recommend HTML or XML pages, with limited JavaScript, and Flash modules that sit like graphics files in the HTML or XML.) Without a complete index entry, the algorithm will not rank the page as highly as it would with a complete one. Optimizing a page is about making sure that the content on the page is structured for easy crawling and accurate indexing.

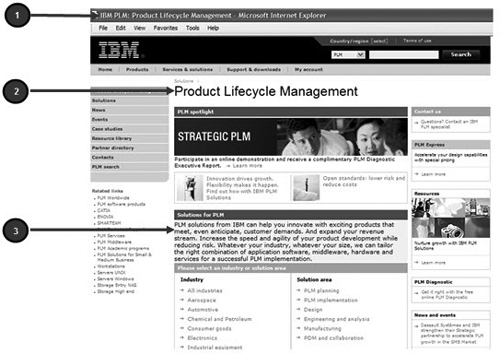

One of the reasons Google does a better job than any other search engine is the tuning of its crawler. Crawlers scan certain elements on a page to determine relevance. They look for parts of the code, in addition to the body copy. They especially look for the <title> tag, which is the text that appears at the top bar of a browser window on the left (number 1 in Figure 4.14). They also look for the <h1> tag or heading for a page (number 2 in Figure 4.14). Then they scan the body copy on a page (number 3 in Figure 4.14). And they look for links. This is very similar to the way users scan a page before determining whether or not to engage with its content. So tuning your pages for Google’s crawler will also help you tune your pages for your users.

Figure 4.14. The ibm.com Product Lifecycle Management page. Item number 1 is how the browser displays the <title> tag. Item number 2 is how the browser displays the <H1> tag or heading. Item number 3 is how the browser displays the body copy. The crawler scans these three elements, first looking for keywords and their derivatives. Note that this page was later optimized. It is used here as an example of how to improve your pages.

(Source: IBM Corp.)

The Google crawler scans the text in the source code for a page. At IBM, when we audit pages, we select View > Source from the browser menu and try to emulate the crawler by searching for the <title> tag, <h1> tag, and placement of the body copy and the links. Then we try to ensure that the chosen keyword appears in those places. That’s easy enough for the <title> tag and <h1> tag. But ensuring this for body copy can get a little tricky. Because we are mostly concerned about how to write for the Web, as opposed to how to code pages for the Web, we will focus on the body copy.

The most important aspect of writing body copy is ensuring that it contains the keywords that appear in the <title> tag. The next most important is the <h1> tag. In the example in Figure 4.14, the keyword is Product Lifecycle Management (PLM). Beyond that simple requirement, there are a variety of techniques you can use to optimize your body copy.

Ensure that Google pulls the text you want it to display in its SERP (the search engine results page, which it shows when it completes a search). This is the 150 characters of text that Google publishes to users between the title and the URL on the SERP (see Figure 4.15). There are two ways to do this. You can type exactly what you want into the <meta content="description"> tag, or you can focus on the first 150 words of the body copy. The easier of the two is to put it into the <meta content="description"> tag, because this gives you some freedom to write a first sentence that is more compelling for humans in your body copy. But, generally speaking, if your first sentence is identical to the 150-character snippet on the SERP, it’s good enough. If it’s compelling enough to get a user to click through from the SERP, it’s compelling enough to put in the first sentence of your body copy.

Figure 4.15. Three listings on Google’s SERP for the keyword Smarter Planet. In the first two cases, the <meta content="description"> tag specifies the copy we want to portray to the target audience to get them to click through. In the third case, Google pulls the first 150 characters of the body copy.

(Source: www.google.com)

Beyond what you want to display on the SERP, you can do a lot of things with the body copy to enhance its position in search engines for your keywords. We will focus on the most important tactics in this section: spelling out acronyms, pumping up keyword density, ensuring keyword proximity, stemming verbs, using synonyms and other related words, using descriptive link text, and bolding for emphasis.

• Spelling out acronyms: In the example in Figure 4.14. the term Product Lifecycle Management is abbreviated PLM. In print, the common style for acronyms and other abbreviations is to spell them out on first reference and never spell them out again. This is not a good tactic for the Web. The crawler needs to see the full unabbreviated form of the keyword in all three primary locations. So, for example, the body copy in Figure 4.14 starts with the abbreviated form. That’s a no-no. It should start by spelling out Product Lifecycle Management (PLM). It can use the abbreviated form in the body copy afterwards. But unlike in print, the abbreviated form should be used only when readability is not affected. Use the spelled-out form as often as possible. That’s what the crawler is looking for. That’s one action item we took when we later optimized that page.

• Pumping up keyword density: After the first sentence, ideally, between 2 and 4 percent of your body copy should contain the keyword in your <title> and <H1> tags. This might seem absurd to writers accustomed to using the entire lexicon available to them to engage the reader. But it is a goal to strive for in Web copy writing. There are ways of pumping up keyword density without overwhelming the reader with repetitive language. The strict rule in the print world that dictates that you should find alternative words if you see the same word twice in a short span of text does not apply on the Web, especially when it comes to keywords. That said, you don’t want to go over the 4 percent rule, lest you invoke the dreaded spam algorithm that Google uses to weed out blatant attempts to trick it into driving traffic to irrelevant content for the sake of ad dollars.

• Ensuring keyword proximity: All things considered, if your keyword contains multiple words, the closer the words are in proximity, the easier it is for the crawler to associate them. For example, if the above body copy contained the phrase managing your product lifecycles, the crawler would have an easier time making the association with the keyword than if it contained the phrase it is important to manage the lifecycle of the products in your portfolio. The words need not be in the same order, or even adjacent to each other, for the crawler to associate them with the keywords in the <title> and <h1> tags. But the closer the better.

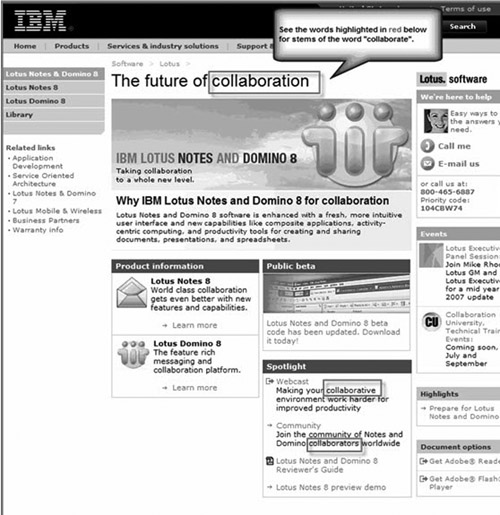

• Stemming: This is the use of alternative grammatical forms of words. For example, from stem you could have stem, stemmed, stemming, stems, etc. Because users will enter keywords in many different forms, you have a better chance of getting search results if you make it a point to stem your verbs in your body copy. Of course, you don’t want to mix tenses. But you can use the gerund (stemming) and the present perfect (stems) form in the same paragraph, for example. Another reason to stem is that it enables you to gain more keyword density without replicating the same words over and over again. And it is relatively easy to mix the different forms of nouns, as in Figure 4.16, to use adjectives in adverbial phrases, and to apply other similar strategies.

Figure 4.16. This example from the IBM site shows stemming with the use of collaboration, collaborative, and collaborators on the page.

(Source: IBM Corp.)

• Using synonyms and other related words: When you do your initial keyword research, you will develop your seed words, then from that you will develop a keyword cloud of related words from your set of seed words. Don’t discard the keyword cloud after you choose your keywords. This is a handy tool to use as you write. For every sentence in the English language, there are something like thirty alternative ways of expressing the same thing with different related words. Chances are, your audience will use the entire range of these expressions, especially considering audience diversity. The more of these you can capture by using the entire keyword cloud, the better your search results will be.

• Using descriptive link text: Because the crawler doesn’t just look at the body copy, but especially focuses on links, it is important that your links be as descriptive as your body text. Don’t just replicate the heading of the site to which you’re linking: Describe the site, preferably with the keywords in your <title> and <h1> tags. And don’t just use generic links like Learn more or Download the PDF. Use the keywords of the page or media piece to which you are linking.

• Bolding for emphasis: Web users’ eyes tend to cue into bullet points, bolding, and other ways of emphasizing text. If you have the opportunity to do this with your keywords, it’s a good practice. It’s good for the crawler and for the user who comes to your site from Google using those keywords. You are less likely to get bounce and more likely to get engagement if it is easy for the user to understand the relevance of your page in a few seconds of scanning.

Many site owners mistakenly believe that ranking high for any term closely related to the content of their page will produce an influx of targeted visitors. Although this may get you more traffic, these high rankings will not always drive qualified visitors to your site or page. Your goal is to find keywords that are relevant to your audience. That means using the words and phrases common to your target audience in your body copy. The above techniques can help you hedge your bets that your diverse audience will use one form or another of the keywords in your cloud, which you developed from your seed words.

In Chapter 5, we will explain how to discover and use not only the keyword phrases that your target audience uses, but their exact language. This involves sophisticated long-tail research and social media mining tactics. Wherever feasible, it’s important to learn as much as possible about your target audience, especially the words and phrases that they use in search and social media contexts. Because Web content is never finished and testing is an integral part of the publishing process, your efforts can start with search and mature into social media as time and resources permit.

Summary

The search-first Web writing methodology is a radical departure from print writing, where you passively attract readers interested in your books and articles. In Web writing, you actively attract an audience that is more likely to find your content relevant if it is written for them with the building blocks of Web content—keywords. This chapter describes the tactics at the core of the search-first writing methodology. The following insights are important to understanding how to put the search-first methodology into practice.

• Define your target audience according to the words and phrases they are likely to enter into Google.

• Research the keywords most often used in Google search queries to maximize the volume of traffic to your pages, while minimizing bounce rates.

• Write your content only after you have done a thorough analysis of how to target your audience with the keywords that your research suggests.

• Implement your keyword research into your writing by ensuring keyword density, proximity, word stemming, and using related words, synonyms, and descriptive link text.

• Measure the effectiveness of your first efforts with an eye toward republishing your content, to reduce bounce rates and improve engagement.

• Continually refine your language to better engage your target audience with relevant content.