3

Human Resource Management

This chapter looks at the management of human resources and examines

• the chief functions of human resource management

• the management of unionized workers

• selected laws and regulations governing the recruitment, hiring, and treatment of employees

Broadcast stations in the same market, with comparable facilities and staffs of similar size, often achieve different levels of success. Some attain their objectives regularly, while others fare poorly. Why?

The reasons may be complex. Often, however, the difference may be traced to the way in which each station manages its personnel. The station that attracts qualified employees, compensates them fairly, recognizes and responds to their individual needs, and provides them with a pleasant working environment is rewarded with the amount and quality of work that lead to success. The station that pays more attention to the return on its financial investment than to its staff is plagued by low morale, constant turnover, and a continuing struggle in the competitive broadcast marketplace.

It has been observed that, “No other element of the broadcasting enterprise can deliver as great a return on investment as its human resources.”1 Recognizing this, many large stations have established a human resources department, headed by a manager or director. Working with the general manager and other department heads, the department is involved in the following functions: (1) staffing, including staff planning and the recruitment, selection, and dismissal of employees; (2) employee orientation, training, and development; (3) employee compensation; (4) employee safety and health; (5) employee relations; (6) trade union relations, if staff members belong to a trade union; and (7) compliance with employment laws and regulations.

In most stations, however, these functions are handled by a number of different people. Typically, department heads are largely responsible for the management of employees in their respective departments. They recommend to the general manager departmental staffing levels, the hiring and dismissal of staff, and salaries and raises. They approve vacation and leave requests, supervise staff training and development, and ensure departmental compliance with legal and regulatory requirements. Similarly, if their staff is unionized, they carry out the terms of the union contract.

The general manager approves staffing priorities, hirings and dismissals, and salaries and raises for employees in all departments. The general manager monitors, also, the station’s compliance with all applicable laws and regulations and with trade union agreements. The business manager is charged with maintaining employee records and processing the payroll.

THE FUNCTIONS OF HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Staffing

Planning

To meet its objectives, a broadcast station must have an adequate number of employees with appropriate skills, both in the station as a whole and in each department. Ensuring that enough qualified staff are available requires the projection of future needs and the development of plans to meet those needs. Together, these activities are known as personnel planning, which consists of five components:

• Job analysis identifies the responsibilities of the job, usually through consideration of the job’s purpose and the duties that must be carried out in order to fulfill that purpose.

• Job description results from the job analysis and includes purpose and responsibilities.

• Job specifications grow out of the job description and set forth the minimum qualifications necessary to function effectively. Typically, they include a certain level of education and experience in similar work. Other specifications vary with the job.

• Workload analysis is an estimate of the type and amount of work that must be performed if the station’s objectives are to be met.

• Workforce analysis involves consideration of the skills of current employees to determine if any of them have the qualifications to handle the job. If the analysis shows that some do, a selection may be made among them. If not, the station probably will seek a qualified candidate outside.2

To illustrate the personnel planning procedure, assume that a television station intends to expand its early-evening newscast from 30 minutes to 1 hour. The workload analysis indicates, among other things, that a co-anchor must be added. The workforce analysis finds that none of the existing news staff is qualified. The job analysis concludes that the chief responsibility is to coanchor the newscast and that additional responsibilities include writing and reporting for both the early and late newscasts. The job description lists the position title and the responsibilities it carries. The job specifications call for a degree in broadcasting or journalism and experience in TV news anchoring, writing, and reporting.

Recruitment

Recruitment is the process of seeking out candidates for positions in the station and, if necessary, encouraging them to apply. Many stations have a policy of filling vacant jobs with current employees, whenever possible. Such a policy can help build morale among all employees, since it shows management’s concern for the individual and suggests that everyone will have an opportunity for advancement. From the station’s standpoint, the practice is advantageous because management knows its employees and their abilities. In addition, the employee is accustomed to working with other station staff and is familiar with the station’s operation. Stations that are part of a group usually post the opening with other stations in the group. Similar advantages apply.

When recruitment takes place externally, the particular vacancy will suggest the most likely sources of applicants. Stations and groups usually post all vacancies on their Web site. Some stations supplement their online postings with advertisements in the local newspaper, especially for clerical positions. Advertisements in national trade magazines—B&C Broadcasting & Cable and TelevisionWeek, for example—may attract the attention of potential employees in a range of professional areas. Publications and Web sites of trade and professional organizations, such as the National Association of Broadcasters and state broadcasting associations, are another means of publicizing job openings. Web-only sites are an additional option. They include Radio Online (http://www.radio-online.com) for radio and Broadcast Employment Services (http://www.tvjobs.com) for television. Both sites offer postings at no charge to stations. Vacancies in radio and television may be advertised at http://www.TvandRadiojobs.com, which charges a listing fee.

Station consultants may be helpful in suggesting candidates for positions, since they are familiar with employees in other markets.

As noted later in the chapter, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) requires most stations to use recruitment sources and notify requesting organizations of every full-time vacancy.

A good source of applicants, particularly for entry-level positions, is the two-year college or university, especially if it has a broadcasting or communication department. Many stations in college and university towns conduct internship programs with such institutions and are able to identify potential employees during the internship. In the absence of an internship program, a call to the institution’s placement office will bring the vacancy to the attention of students. Most placement offices keep files on recent graduates and will alert those with appropriate qualifications. If the office distributes a regular listing of positions to interested alumni, an even larger number of potential applicants will be reached.

Word of actual or anticipated vacancies spreads quickly through most stations. It is common, therefore, for employees to carry out informal recruiting by notifying friends and acquaintances. Additionally, many stations ask employees to suggest people who may be interested.

Most radio and television stations keep a file of inquiries about possible jobs. Persons visiting the station to ask about openings often are invited to complete an application for employment, even if no vacancy exists. The application may be filed for possible use later. A similar practice is followed with letters of inquiry. Obviously, the value of the file diminishes with the passage of time as those making the inquiry find other employment, and many stations remove from the file applications that are more than six months old. However, it may be a useful starting point.

Selection

When recruitment has been completed, the station moves to the selection process. This involves the identification of qualified applicants and the elimination of those who are not. Ultimately, it leads to a job offer to the person deemed most likely to perform in a way that will assist the station in meeting its objectives.

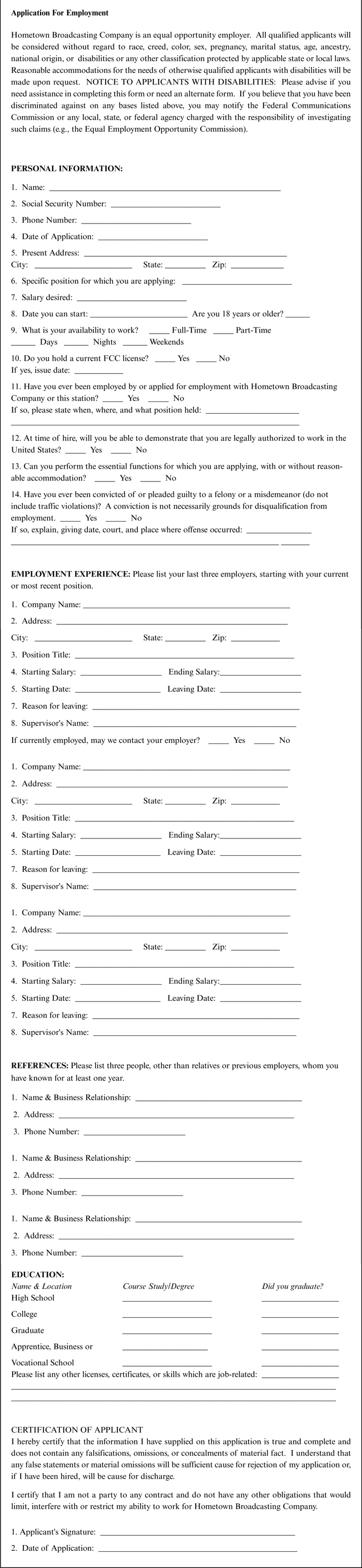

Stations typically require applicants to complete an employment application form. Stations and groups often include the form on their Web site. Generally, it asks for personal information, such as name, address, and telephone number, as well as details of the position sought, education and work experience, and the names and addresses of references. An example of an application for employment form is shown in Figure 3.1. It calls for other information that the station may use in the selection, such as legal authorization to work in the United States and criminal record. In addition, it states the station’s policy on nondiscrimination in employment, which will be discussed later in the chapter.

Figure 3.1 Sample of an application for employment in a broadcast station.

The station may ask applicants to take a test to prove that they have the skills claimed on the form. Candidates for a clerical position, for example, may have to demonstrate speed and accuracy on a word-processing test. Some stations use writing tests for entry-level positions in the newsroom.

Applicants for many positions prefer to provide the station with a résumé, in addition to or instead of a completed application form. The résumé permits the person seeking employment to emphasize qualifications and to provide more details than most application forms can accommodate.

For on-air positions, the station usually asks applicants for an air check or tape containing examples of their work. In radio, the aim is to identify persons whose voice and style match station format, or whose news delivery commands credibility. In addition to considering voice, the television station is interested in physical appearance and manner of presentation.

Using the employment application form or résumé and, if appropriate, test results and the on-air samples, the station can reduce the list of applicants to those who match most closely the job qualifications. The process of elimination usually continues until only a few names remain.

At this point, interviews may be arranged with those whose applications will be pursued. However, many stations prefer to carry out background and reference checks before proceeding, and with good reason.

Applicants seek to present their education, experience, and skills in the most favorable light. Most list accomplishments of which they are proud and ignore their shortcomings. Some even stretch the truth and give themselves job titles they never held or claim to be proficient in tasks for which they have only rudimentary ability. Furthermore, listed references are likely to be persons who are disposed favorably to the applicant.

Checking on the education of applicants usually is not difficult. A telephone call, fax, or letter to a school, college, or university can produce the required information.

The work experience check sometimes presents problems, especially if the applicant has held jobs with several stations over a number of years. However, the stations’ personnel files should contain records of the candidate’s job titles and responsibilities, employment dates, and salary.

Many stations try to obtain from previous employers details of the applicant’s quality of work, ability to get along with colleagues and superiors, strengths and weaknesses, and the reason for leaving. It is not unusual to discover that managers under whom applicants have worked at other jobs have moved in the meantime. When this happens, perseverance is required to track down the manager and, in the event of failure, to find others who remember the applicant and are willing to respond to questions.

Obtaining responses is difficult for another reason: the increasing incidence of legal actions by persons receiving negative recommendations. For that reason, it is not unusual for employers to provide only confirmation of a former employee’s dates of employment, job title, and responsibilities.

If the applicant has a job, questions may be posed to the current employer. But stations usually do so only with the approval of the applicant. Permission of the applicant is required, also, if the station plans to carry out a credit check. This practice is not widespread, but many stations conduct such a check on prospective employees whose job will entail the handling of money.

Checks with the references listed by the applicant usually concentrate on the circumstances through which the reference and the applicant are acquainted, and on personal and, whenever appropriate, professional strengths and weaknesses about which the reference can provide information.

If the background and reference checks support the station’s preliminary conclusions about the applicant’s qualifications, an interview will be scheduled. Of all the steps involved in the selection process, none is more important than the interview. The station will use the results to make a hiring decision. A good choice of candidate will add to the station’s competitive strength. A poor choice may lead to a decision to dismiss the chosen candidate after only a short period of employment, leading to yet another search with its attendant expenditures of time, money, and effort.

Interviews are time-consuming for station employees who will be involved and may be costly for the station if the interviewees live in distant cities and the station meets the expenses of travel, meals, and accommodation. However, while application forms, tests, résumés, air checks or tapes, and background and reference checks yield a lot of information about applicants and their qualifications, only a face-to-face interview can provide insights into those personal characteristics that often make the difference between success and failure on the job.

The interview gives the station the opportunity to make a determination about the applicant’s suitability based on observation of factors such as appearance, manners, personality, motivation, and communication abilities. The applicant’s awareness of commercial broadcasting’s philosophy, practices, and problems, and their attitudes toward them also may be gleaned from responses to questions. In addition, conclusions may be drawn about the applicant’s ability to fit into the station.

Interviewing procedures vary. Some stations prefer an unstructured, freewheeling approach, while others follow a structured and formal method. The general manager may take part or merely approve or disapprove the hiring recommendation. In some stations, only the head of the department in which the vacancy exists participates; in others, the heads of all departments may be involved. Some stations include staff in the interviewing.

Whatever procedure is followed, the principal objective of the interview should be the same: an assessment of the candidate’s suitability for the position. Of course, the interview may be used to obtain from the applicant additional details about qualifications or clarification of information contained on the application form or résumé. The interviewer may wish to provide the applicant with specific information about the station and the job to be filled. But such exchanges of information should be used only as a means of satisfying the principal objective, and not merely to fill the allotted time.

Those involved in conducting the interview can take certain actions to try to ensure that the objective is achieved:

Before the Interview

1. Become fully familiar with the responsibilities of the position to be filled and the education, experience, and skills necessary to carry them out. This will permit an understanding of what will be required of the new employee, and of the relative importance of education, experience, and skills.

2. Review the candidate’s application form or résumé and, if appropriate, test results and air check or tape. This will help to assess the candidate’s qualifications and suggest possible questions for the interview.

3. Confirm the date and time of the interview and ensure that enough time has been allowed for it.

4. Give instructions that the interview must not be interrupted by other staff or by telephone calls.

During the Interview

1. Establish a friendly climate to put the interviewee at ease. This can be accomplished by a warm handshake, a smile, and some small talk.

2. Ask only job-related questions. Questions that do not lead to an assessment of qualifications for the position are wasted. They also may be dangerous if they suggest discrimination based on age, sex, or religion, for example.

3. Give the interviewee an opportunity to speak at some length and to answer questions fully. One method of doing this is to pose openended questions. If necessary, press the candidate with follow-up questions to obtain additional information.

4. Listen to the responses to the questions. Some interviewers prefer to make written notes during the interview, though this can be disturbing for an interviewee who is required to look at the top of someone’s head during what should be a face-to-face exchange.

5. Give additional information about the job and the station to ensure that the candidate has a full understanding of them. Details of the full range of responsibilities, working hours, salary, and fringe benefits, and of the station’s organization, goals, and role in the community are among the items that could be covered.

6. Allow time for the candidate to ask questions. In giving details of the job and the station, many interviewers assume that they are providing all the information a candidate requires. However, the interviewee may also be interested in considerations that are not job-related, such as the cost of housing, the quality of the public schools, and employment opportunities in the community for a spouse.

7. Pace the interview so that all planned questions are covered. Omission of questions and the responses may make a hiring decision difficult.

8. Terminate the interview politely. One way to end is to advise the candidate when a decision on filling the position will be made.

9. Ensure that the candidate is shown to the next appointment on the schedule. If the interview is the final appointment, arrange for the candidate to be accompanied to the exit.

After the Interview

Record the results of the interview immediately. Some stations use an evaluation form that lists the qualifications for the job and permits the interviewer to grade each candidate on a scale from “poor” to “outstanding” on each. Other stations ask the interviewer to prepare a written memorandum assessing the candidate’s strengths and weaknesses. When interviews with all candidates have been completed, the memoranda are used in making a recommendation.

Oral evaluations are not satisfactory, since they leave a gap in the station’s employment records. This leads to problems if questions about hiring practices are raised by an unsuccessful candidate or the FCC.

As soon as the decision has been taken to hire one of the interviewed candidates, a job offer should be made promptly. A telephone call will establish if the candidate is still available and interested, and if the offer is acceptable.

To ensure that the station’s records are complete, and to avoid misunderstandings, a written offer of employment should be mailed, with a copy. Among other information, it should include the title and responsibilities of the position, salary, fringe benefits, and the starting date and time. If it is acceptable, it should be signed and dated by the new employee and returned to the station, where it will become part of the employee’s personnel file. The copy should be retained by the employee.

A letter should be mailed to the unsuccessful candidates, also, advising them of the outcome. They may not welcome the news, but they will appreciate the action, and the station’s image may be enhanced as a result.

The station should keep records of all recruitment, interviewing, and hiring activities to satisfy FCC requirements, discussed later. The documentation may be useful in identifying effective procedures, and it may be necessary to satisfy inquires about, or challenges to, the station’s employment practices.

Dismissals

Staff turnover is a normal experience for all broadcast stations. It is a continuing problem for stations in small markets, where many employees believe that a move to a larger market is the only measure of career progress.

Stations in markets of all sizes are familiar with the situation in which a staff member moves on for personal advancement. In such circumstances, the parting usually takes place without hard feelings on the part of either management or employee.

Another kind of staff turnover is more difficult to handle. It results from a station’s decision to dismiss an employee, an action that may send panic waves through the station. If it involves a member of the sales staff, it may also bring reactions from clients. If an on-air personality is involved, the station may hear from the audience.

Of course, some dismissals do not reflect ill on affected employees. Changes in station ownership, the format of a radio station, or locally produced programming at a television station may result in the termination of some employees. Economic considerations, such as those occasioned by inmarket radio station consolidation, often lead to reductions in staff.

The majority of dismissals, however, stem from an employee’s work or behavior. No station can tolerate very long a staff member who fails to carry out assigned responsibilities satisfactorily. Nor can a station continue to employ someone who is lazy, unreliable, uncooperative, unwilling to accept or follow instructions, or whose work is adversely affected by reliance on abuse of alcohol or drugs.

This is not to suggest that management should stand by idly while an employee moves inevitably toward dismissal. Several steps may be taken to avoid such an outcome. For example, a department head should point out unsatisfactory work immediately and suggest ways to improve. The employee should be warned in writing that failure to improve could lead to dismissal. A copy of the warning should be placed in the employee’s file.

Similarly, the supervisor’s awareness of the employee’s inability or unwillingness to act in accordance with station policies should be brought to the attention of the noncomplying staff member. Action should be taken when the behavior is observed or reported, since tolerating it may suggest that it is acceptable. If the station has a written policy against the behavior, it should be sufficient to draw the employee’s attention to it. Again, it would be wise to write an appropriate memorandum to the employee and to place a copy in the employee’s file. The memorandum should indicate clearly that continuation of the behavior may result in dismissal.

Management actions of this kind may not lead to improvement or correction, but they will eliminate the element of surprise from a dismissal decision, and they will show that the station has taken reasonable steps to deal fairly with the employee.

If an employee is to be dismissed, the way in which the decision is reached is important. So, too, is the way in which it is carried out, since it is certain to produce a reaction from other employees. The most important reason for caution, however, is federal and state legislation.

Attorney John B. Phillips, Jr., has prepared a set of guidelines for management to follow before discharging an employee.3 First, he recommends a review of the employee handbook to make sure that the station management has complied with all procedures identified therein. That review should be followed by a review of the employee’s personnel file to determine if the documentation contained in it is sufficient to warrant the termination. It should show, for example, that the employee has been advised of the possibility of dismissal and has had ample opportunity to correct any problems or failures to perform as required.

Next, managers should evaluate the possibility of a discrimination or wrongful discharge claim. (Major federal laws on discrimination are described later in the chapter.) The following are among the questions that should be considered:

• How old is the employee?

• Is the employee pregnant?

• How many minority employees remain with the station?

• Does the employee have a disability?

• Who will replace the employee?

• How long has the employee been with the station?

• Does the documentation in the file support termination?

• Was the employee hired away from a long-time employer?

• Has the employee recently filed a workers’ compensation claim or any other type of claim with a federal or state agency?

• Has the reason for termination been used to terminate employees in the past?

Phillips lists other questions that may have legal implications but that are primarily practical in nature:

• If the termination is challenged, can the station afford adverse publicity?

• To what extent has the station failed the employee?

• Assuming that the employee is not terminated and the problem is not removed, can the station tolerate its continuation?

• Is the employee the kind of person who is likely to “fight back” or file suit?

• What impact would termination have on employee morale and employer credibility? What about failure to terminate?

• Has the immediate supervisor had problems with other employees in the department?

• Does the employee have potential for success in a different department?

• Are there nonwork-related problems that have created or added to the employee’s problems at work?

• Has the employee tried to improve?

• Even if the termination is legally defensible, is it a wise decision?

Having reached a tentative decision to terminate, a manager may wish to let a noninterested party evaluate the decision before acting. However, this should not be viewed as a substitute for seeking legal advice if problems are anticipated.

If it is determined that dismissal is appropriate, Phillips suggests a termination conference with the employee. He offers the following guidelines:

1. Two station representatives should be present in most cases.

2. Within the first few minutes, tell the employee that he or she is being terminated.

3. Explain the decision briefly and clearly. Do not engage in argument or counseling, and do not fail to explain the termination.

4. Explain fully any benefits that the employee is entitled to receive and when they will be received. If the employee is not going to receive certain benefits, explain why.

5. Let the employee have an opportunity to speak, and pay close attention to what is said.

6. Be careful about what you say, since anything said during the termination conference can become part of the basis of a subsequent employee claim or lawsuit. In other words, do not make reference to the employee’s sex, age, race, religion, or disability or to anything else that could be considered discriminatory.

7. Review the employment history briefly, commenting on specific problems that have occurred and the station’s attempts to correct them.

8. Try to obtain the employee’s agreement that he or she has had problems on the job or that job performance has not been satisfactory.

9. Take notes.

10. Be as courteous to the employee as possible.

11. Remember that you are not trying to win a lawsuit; you are trying to prevent one.4

What the employee was told and what the employee said should be included in the documentation of the conference, and it should be signed by all employer representatives in attendance.

Orientation, Training, and Development

All newly employed staff are new even if they have already worked in a radio or television station. They are with new people in a new operation. Accordingly, they should be introduced to other employees and to the station, a process known as orientation.

The introduction to other staff members may be accomplished through visits to the various departments, accompanied by a superior or department head. Such visits permit the new employee to meet and speak with colleagues and to develop an understanding of who does what. Some stations go further and require newcomers to spend several hours or days observing the work of personnel in each department.

An employee handbook designed for all staff often is used to introduce the new employee to the station. Typically, it includes information on the station’s organization; its policies, procedures, and rules; and details of employee benefit programs and opportunities for advancement. Among the items usually covered in the section on policies, procedures, and rules are the following: working hours, absenteeism, personal appearance and conduct, salary increases, overtime, pay schedule, leaves of absence, outside employment, and discipline and grievance procedures. Information on employee benefits might include details of insurance and pension programs, holidays and vacations, profit-sharing plans, stock purchase options, and reimbursement for educational expenses.

One of the major purposes of an employee handbook is to ensure that all staff are familiar with the responsibilities and rewards of employment, there-by reducing the risk of misunderstandings that could lead to discipline or dismissal. It is important, therefore, that the employee read it and have an opportunity to seek clarification or additional details.

Training is necessary for a new employee who has limited or no experience. Often, it is necessary for an existing employee who moves to a different job in the station. Training is also required when new equipment or procedures are introduced.

Closely allied to training is employee development. Many stations believe that the existing staff is the best source of personnel to fill vacated positions. However, it will be a good source only if employees are given an opportunity to gain the knowledge and skills required to carry out the job.

A successful development program results in more proficient employees and, in turn, a more competitive station. Workshops and seminars are frequent vehicles for employee development. Many stations encourage attendance at professional meetings and conventions, as well as enrollment in college courses.

However, probably the most fundamental part of a development program is a regular appraisal session during which the department head reviews the employee’s performance. The following are among the functions that may be evaluated:

• attendance and punctuality

• commitment to task

• knowledge of company policies and procedures

• professional appearance

• quality and quantity of work

• spoken and written communication

• teamwork and interaction with others

• versatility

Many stations use a performance review form with a grading scale. After grading all factors, the department head invites the employee to sign the form and indicate agreement or disagreement. In the event of disagreement, the employee may appeal the evaluation to the general manager. One copy of the form is retained by the employee and a second is placed in the employee’s personnel file.

Performance reviews should enable employer and employee to exchange job-related information candidly and regularly. In addition to providing an opportunity to identify employee strengths, they also permit the department head to discuss weaknesses and ways in which they may be corrected, and to assess candidates for merit pay increases and promotion. At the same time, they may result in a demotion or dismissal.

A more comprehensive approach to employee development is afforded by the practice known as management by objectives (MBO), enunciated by Peter Drucker in The Practice of Management. Designed as a means of translating an organization’s goals into individual objectives, it involves departmental managers and subordinates, jointly, in the establishment of specific objectives for the subordinate and in periodic review of the degree of success attained. At the end of each review session, objectives are set for the next period, which may run for several months or an entire year.

The MBO approach offers many advantages. It can lead to improved planning and coordination through the clarification of each individual’s role and responsibilities, and the integration of employees’ goals with those of the department and the station. Communication can be enhanced as a result of interaction between managers and subordinates. In addition, it can aid the motivation and commitment of employees by involving them in the formulation of their objectives.

However, if the practice is to be successful, objectives must be attainable, quantifiable, placed in priority order, and address results rather than activities. Furthermore, rewards must be tied to performance. If they are not, cynicism probably will result and the worth of the endeavor will be diminished.

Compensation

The word compensation suggests financial rewards for work accomplished, but staff members seek other kinds of rewards, too. Approval, respect, and recognition are expectations of most employees. So, too, are working conditions that permit them to perform their job effectively and efficiently. The station that recognizes and rewards individual employee contributions and achievements will make employees feel good about themselves and the station. Their positive feelings will be enhanced if the station provides a pleasant work environment that facilitates the fulfillment of assigned responsibilities.

Salary

The Fair Labor Standards Act sets forth requirements for minimum wage and overtime compensation. It stipulates that employees must be paid at least the federal minimum wage. Stations in states with a rate higher than the federal minimum must pay at least the state minimum.

The act exempts from minimum wage and overtime regulations executive, administrative, and professional employees and outside salespeople, or those who sell away from the station. Small market stations also may exempt from overtime regulations announcers, news editors, and chief engineers.

As the major part of employees’ compensation package, salaries must be fair and competitive. They must recognize each employee’s worth and must not fall behind those paid by other employers for similar work in the same community. A perception of unfairness or lack of competitiveness may lead to staff morale problems and turnover.

Many stations pay bonuses to all employees. A Christmas bonus is common. Some stations provide employees with a cash incentive bonus, based on the station’s financial results. Both kinds of bonus can generate goodwill and contribute to the employee’s feelings of being rewarded.

Financial compensation for sales personnel differs from that of other staff and will be discussed in Chapter 5, “Broadcast Sales.”

Benefits

Fringe benefits provide an additional form of financial compensation. Benefit programs vary from station to station and market to market. Some benefits cover employees only, while others include dependents. The cost of benefits may be borne totally by the station or by both the station and the employee.

The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) conducts an annual survey of television employee compensation and fringe benefits. It lists the following benefit programs:

• Health benefits: Hospitalization, surgical, and major medical insurance coverage for both employees and their dependents. Most stations share the cost with the employee.

• HMO: Employee and dependent participation in a health maintenance organization. Again, the cost typically is shared.

• Dental: Available to employees and dependents on a cost-sharing basis.

• Vision: Offered to employees and their dependents, with a sharing of cost.

• Accidental death: A majority of stations provide it only for employees and meet the cost in full.

• Group life insurance: Mostly provided for employees only and fully paid for by the employer.

• Disability: Restricted to employees and covers both short- and long-term disability. Generally paid in full by the employer.

• Pension plan: Provided by fewer than one-half of stations, most of which pay the full cost.

• 401-K plan: An employee may defer taxation on income by diverting a portion of income into a retirement plan. In most stations offering the plan, contributions are made by both the employer and the employee.

• Education/career development: Some stations encourage employees to develop their knowledge and skills through courses of study, workshops, seminars, and so on. They offer tuition reimbursements for courses completed, and many cover the cost of participation in workshops and seminars.5

This list is not exhaustive. Among other benefit programs offered by stations are:

• Paid vacation and sick leave: The amounts usually are determined by length of service.

• Paid holidays: These include federal, state and, occasionally, local holidays.

• Profit sharing: Part of the station’s profit is paid out to employees through a profit-sharing plan. The amount of the payment usually is determined by the employee’s length of service and current salary.

• Employee stock option plan: This benefit offers an opportunity for an employee to purchase an ownership interest in the station through payroll deductions or payroll deductions matched by the employer. Some employers give stock as a bonus.

• Thrift plan: The station pays into an employee’s thrift plan (savings) account in some proportion to payments made by the employee.

• Legal services: The employer usually pays the full cost for services resulting from job-related legal actions.

• Jury duty: To ensure that employees on jury duty do not suffer financially, stations make up the difference between the amount paid for jury service and regular salary.

• Paid leave: Some stations grant paid leave to employees attending funerals of close family members or performing short-term military service commitments, for example.

Good working conditions and a fair, competitive salary and fringe benefits program contribute much to an employee’s attitude toward work and the employer. However, a pleasant working environment will not substitute for a salary below the market rate. Likewise, a good salary may be perceived as a poor reward for having to tolerate unreliable or antiquated equipment or a superior who is quick to criticize and slow to praise. In addition, fringe benefits will not be enough to make up for a station’s failure to provide satisfactory working conditions or salaries.

Safety and Health

The workplace should be pleasant, but it must be safe and healthy. If it is not, the result may be employee accidents and illnesses, both of which deprive the station of the services of personnel and cause inconvenience and possibly added costs for the employer.

There is another important reason for protecting the safety and health of staff. Under the terms of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, an employer is responsible for ensuring that the workplace is free from recognized hazards that are causing, or are likely to cause, death or serious physical harm to employees. Many states have similar requirements. The act established the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which has produced a large body of guidelines and regulations. Many deal with specific professions, but a significant number apply to business and industry in general, including broadcasting.

Among general OSHA requirements imposed on all employers are the following:

• to provide potable water and adequate toilet facilities

• to maintain in a dry condition, so far as practicable, every workroom

• to keep every floor, working place, and passageway free from protruding nails, splinters, loose boards, and unnecessary holes and openings

• to remove garbage in such a manner as to avoid creating a menace to health, and as often as necessary or appropriate to maintain the place of employment in a sanitary condition

• to provide sufficient exits to permit the prompt escape of occupants in case of fire or other emergency

Some requirements are designed to protect employees who work closely with electrical power, heavy equipment, and tall structures, such as transmitter towers.

Even conscientious adherence to OSHA regulations does not guarantee an accident-free workplace. If an employee dies as a result of a work-related incident, or if three or more employees have to be hospitalized, OSHA requires that the employer report the fatality or hospitalization within eight hours to its nearest area office.

Obviously, the station cannot accept total responsibility for the safety and health of staff. Employees have an obligation to take care of themselves, and the 1970 act requires them to comply with safety and health standards and regulations. However, the station should take the lead in satisfying appropriate guidelines and regulations, requiring staff to do likewise, and in setting an example of prudent safety and health practices for employees to follow.

Employee Relations

Employees differ in their aspirations. Some may be content in their current job, while others may be striving for new responsibilities through promotion in their departments or transfer to another area of station activity. Still others may be using their present position as a stepping-stone to a job with another station.

But most employees share the need to feel that they are important, that they are making a valuable contribution to the station, and that their efforts are appreciated. Accordingly, the relationship between management and staff is important.

Good employee relations are characterized by mutual understanding and respect between employer and employee. They grow out of management’s manifest concern for the needs of individual staff members and the existence of channels through which that concern may be communicated.

Much of the daily communication among staff is carried out informally in casual conversations in hallways, the lounge, or the lunchroom. Its informality should not belie its potential, for either good or ill. More rumors probably have started over a cup of coffee than anywhere else.

Managers should use the informality offered by a chance encounter with an employee to display those human traits of interest and caring that help set the tone for employer–employee relations. A smile, a friendly greeting, and an inquiry about a matter unrelated to work can do much to convince staff of management’s concern. In addition, they can help establish an atmosphere of cooperation and build the kind of morale necessary if the station is to obtain from all employees their best efforts.

Informal communication is important, but limited. To guarantee continuing communication with staff, managers rely heavily on the printed word. A letter or E-mail to an employee offering congratulations on an accomplishment, or a memorandum posted on the bulletin board thanking the entire staff for a successful ratings book, are examples.

Many stations communicate on a regular basis through a newsletter or magazine. Such publications often are a combination of what employees want to know and what management believes they need to know. They want to know about their colleagues. Anniversaries, marriages, births, hobbies, travels, and achievements find their way into most newsletters. Employees also are interested in station plans that may affect them.

Often, employee information needs are not recognized by management until they have become wants. Managers who are in close communication with employees recognize the desirability of keeping them advised on a wide range of station activities. The newsletter is a useful mechanism for telling staff members what they need to know by not only announcing but explaining policies and procedures, reporting on progress toward station objectives, and clarifying any changes in plans to meet them. Rumor and speculation may not be eliminated, but this kind of open communication should reduce both.

Bulletin boards are used in many stations to provide information on a variety of topics, from job openings to awards won by individuals and the station. Some stations permit staff to use the boards for personal reasons, to advertise a car for sale or to seek a babysitter, for example.

To a large extent, memoranda, newsletters, and bulletin boards reflect management’s perceptions of employee information wants and needs. The ideas and concerns of nonmanagement staff are more likely to be expressed orally, to colleagues and superiors. Regular departmental meetings provide a means of airing employee attitudes.

When concerns are of a private nature, most employees are reluctant to raise them in front of their colleagues. Recognizing this, many department heads and general managers have an open-door policy so that staff may have immediate access to a sensitive and confidential ear.

The perceptions of employees often are valuable, not only in enabling management to be apprised of their feelings, but in bringing about desirable changes. Suggestions should be solicited from staff. Some stations go further and install suggestion boxes, awarding prizes for ideas that the station implements.

Because of the interdependence of employees and the need for teamwork, many stations encourage a cooperative atmosphere through recreational and social programs. Station sports teams, staff, and family outings to concerts, plays, and sports events, and picnics and parties are examples of activities that can help develop and maintain a united commitment to the station and its objectives.

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND TRADE UNIONS

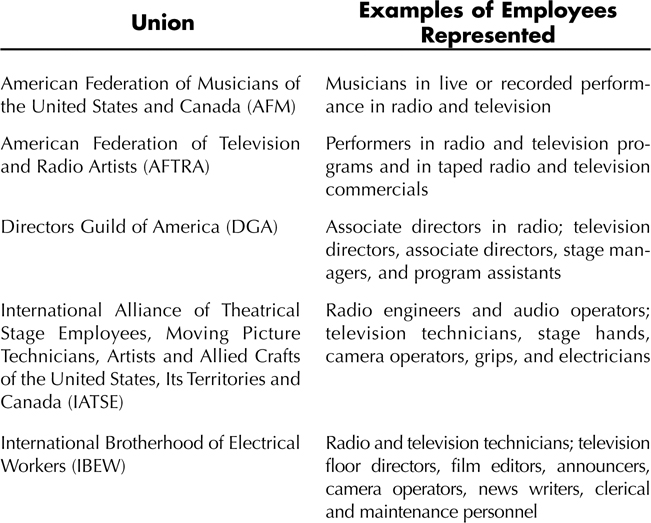

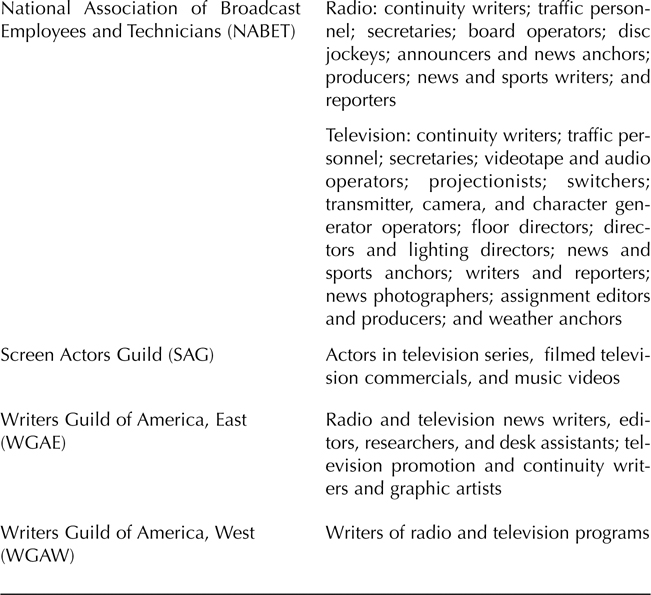

Relations between management and employees in many stations, particularly in large markets, are influenced by employee membership in a trade union. Among the major unions that represent broadcast personnel are the following:

The basic unit of a national or international union is the “local” union, which represents employees in a common job in a station or limited geographic area.

Like all employees, union members seek approval, respect, and recognition, and expect a safe and healthy workplace. They have similar concerns about salaries, fringe benefits, and job security.

However, management’s treatment of unionized employees differs from that in nonunion stations. Take, for example, the matter of complaints. A nonunion employee generally presents the complaint directly to the supervisor or department head and, if necessary, to the general manager. If the employee is a member of a union, the complaint usually will be presented to management by a job steward. This procedure is one of many detailed in the document that governs management–union employee relations: the union agreement or contract.

The Union Contract

The union contract covers a wide range of content and reflects the interests and needs of the employees covered by it. Creative personnel may be concerned about their creative control and the way in which they are recognized in program credits. Technical staff, on the other hand, may be much more interested in the possibility of layoffs resulting from new equipment or the use of nontechnical personnel in traditionally technical tasks.

Most contracts contain two major categories of clauses: economic and work and relationship.

In the economic category, provisions on wages and fringe benefits dominate. The contract will set forth hourly rates of pay, premium rates for overtime and holiday work and, in some cases, cost-of-living adjustments. Among the fringe benefits generally covered are paid vacations and sick leave, insurance, pension, severance pay, and paid leave for activities such as jury duty.

The work and relationship section usually contains some or all of the following provisions:

• Union recognition: The station recognizes the union as the bargaining unit for employees who are members of the union and agrees to deal exclusively with it on matters affecting employees in the unit.

• Union security: The union may require, and the station may agree, that all existing employees in the bargaining unit become and remain members of the union and that new employees join the union within a specified period. Such a requirement is not permitted in so-called “right-to-work” states.

• Union checkoff: The station agrees to deduct from the wages of union members all union dues, initiation fees, or other assessments, and to remit them promptly to the local union.

• Grievance procedure and arbitration: This is a description of the procedure whereby employees may present or have grievances presented to their supervisors and, if necessary, the general manager. If the grievance is not withdrawn or settled, the contract may provide for its presentation to an arbitrator, whose decision will be final and binding on the station, union, and employee during the term of the contract.

• No strike, no lockout: Contracts in which the grievance procedure requires the use of an arbitrator to settle grievances usually contain a clause forbidding strikes, work stoppages, or slowdowns by employees, and lockouts by management.

• Seniority: Most unions insist on the use of seniority in management decisions on matters such as promotions, layoffs, and recalls. Preference in promotion is given to employees with the longest service to the station, provided that the employee has the qualifications or skills to perform the work. In the same way, senior employees will be the last to be affected by layoffs and the first to be recalled after a layoff.

• Management rights: The contract recognizes the responsibility of station management to operate the station in an orderly, efficient, and economic way. Accordingly, the station retains the right to make and carry out decisions on personnel, equipment, and other matters consistent with its responsibility.

Many other provisions may be contained in the contract, including clauses on procedures for suspension or discharge of employees, the length and frequency of meal breaks, reimbursement to employees for expenses incurred in carrying out their work, and safety conditions in the station and in company vehicles. Many contracts also contain clauses permitting the station to engage nonstation employees to carry out work for which employees do not have the skill, and jurisdictional provisions stating which employees are permitted to carry out specific tasks.

Union Negotiations

The contract between a broadcast station and a labor union represents a mutually acceptable agreement and is the result of bargaining or negotiations between the two parties. To ensure that it serves the best interests of the station and its employees, management should take certain actions before and during the negotiations, and after the contract is signed.

Before the Negotiations

1. Assemble the negotiating team. The team should include someone familiar with the station’s operation, usually the general manager. Familiarity with labor law or labor relations is desirable and, for that reason, an attorney often is part of the team. If an attorney is not included, the station should obtain legal advice on applicable federal, state, and local requirements pertaining to bargaining methods and content.

2. Designate a chief negotiator to speak for the station. The person selected should have good communication skills, tact, and patience.

3. Ensure that members of the negotiating team are familiar with the existing contract and with clauses that the station wishes to modify or delete, and the reasons. They should also be aware of the union’s feelings about the current contract and any changes it is likely to seek.

4. Determine the issues to be raised by the station and those likely to be raised by the union.

5. Establish the station’s objectives on economic as well as work and relationship matters.

6. Anticipate the union’s objectives.

7. Determine the station’s positions and prepare detailed documentation to support them. In most cases, the station will identify provisions it must have and others on which it is willing to compromise.

During the Negotiations

1. Take the initiative. One method is to put the union in the position of bargaining up from the station’s proposals. For example, the station may prepare a draft of a written contract for the negotiations, thereby placing on the union the burden of showing the reasons to change it.

2. Listen carefully to union requests and ask for clarification or explanation so that they may be understood fully. This will permit the station’s team to prepare counterproposals or indicate parts of the proposed contract that meet the union’s concerns or needs.

3. Keep an open mind. Refrain from rejecting union requests out of hand. Remember that, like the station, the union starts by asking for more than it expects to obtain and that the final contract will reflect compromises by both parties.

4. Be firm. An open mind and flexibility should not lead the union to believe that the station team is weak and can be pushed around. The station’s chief negotiator should exhibit firmness when necessary, and support the station’s arguments with a rationale and documentation.

5. Avoid lengthy bargaining sessions, since a tired and weary negotiating team may agree to provisions that prove to be unwise later.

6. Ensure that the language of the contract is clear and unambiguous. A document that is open to misunderstanding or misinterpretation will be troublesome to station management.

After the Contract Is Signed

1. Follow the contract diligently and expect the union to do the same.

2. Ensure that all department heads and other supervisory personnel are familiar with the contract. If they are not, and they fail to adhere to it, trouble could result.

Reasons for Joining a Union

Broadcast union members are found most often in large-market radio and television stations. However, that does not mean that stations in smaller markets are immune to attempts to organize employees. In addition, such organizing often results not from the strength of a union but from management’s insensitivity to employee interests and needs.

Management that values its staff and treats them fairly may never experience a threat of unionization. Management that fails to do so may confront an attempt due to one or more of the following factors:

1. Economic

A. Salaries that fall behind those of the competition in the market.

B. Pay rates that are not based on differences in skills or the work required.

C. Fringe benefits that do not match those of competing stations in the market.

2. Working Conditions

A. Absence of guidelines or policies on matters such as promotions, merit pay increases, and job responsibilities.

B. A workplace characterized by dirty offices; poor lighting, heating, and ventilation; unreliable equipment; and safety or health hazards.

3. Management Attitudes and Behavior

A. Noncommunicative management, which leads, inevitably, to speculation, gossip, and rumor. This is particularly dangerous when changes are made without explanation in personnel, equipment, or operating practices.

B. Unresponsiveness to employee concerns. Employee questions that go unanswered often become major problems, especially if employees believe that management is trying to conceal information on actions that may affect their status or job security.

C. Favoritism. If management treats, or is perceived as treating, some employees differently from others, resentment may occur.

D. Discrimination. Even though discrimination is illegal, management actions may be interpreted by some employees as being discriminatory and based on considerations of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, or disability.

E. Ignoring seniority. Many employees believe that seniority and dedication to a station over a long period should be recognized by management in decisions on matters such as promotions. Union organizers will promise to obtain management recognition of seniority.

F. Us versus them. Management that encourages its department heads and other supervisors to put a distance between themselves and their staff and to establish a combative rather than a cooperative environment will meet with resentment and distrust from most employees.

4. The Troublemaker

• Most stations are familiar with the complainer, the person who finds fault with most things or, failing to find a problem, invents one. In some cases, the complainer goes further and becomes an agitator, claiming that a union would meet every employee concern and solve every problem. Often, the arguments sound so persuasive that other employees go along and the likelihood of unionization becomes real.

5 Competing Station

• Union organization of staff at a competing station may result in an attempt at unionization, particularly if it succeeds in obtaining better salaries, fringe benefits, and terms and conditions of employment at that station.

Working with Unions

If, despite efforts to prevent it, a union is organized, management should view it not as a threat but as an opportunity to work cooperatively toward identified goals. That may be easier in theory than practice, but most union members recognize that their job satisfaction depends largely on the degree of success the station attains.

To help in any adjustment to the presence of a union, the following pointers are suggested:

1. Unionism is an accepted fact. Management must recognize that unions generally have reached a point of very high efficiency in bargaining and maintaining strength. Learn to live and work with them when necessary.

2. Management should take a realistic view of all mutual agreements and be very careful about altering, modifying, or making concessions in the established contractual arrangement.

3. Remember that rights or responsibilities that have been relinquished are hard to regain at the bargaining table. Similarly, granting concessions on grievances that have not been properly ironed out can cause future trouble, and rarely brings goodwill or satisfaction to the parties concerned.

4. Supervisors should be vigorously backed up. This does not imply that errors should be defended, but supervisors need support to maintain morale and company strength.

5. Dual loyalty is possible. In pursuing a positive approach, management must realize that in a well-run company the majority of clear-thinking union members know that a strong and progressive management is their best guarantee of security.

6. In employee communications, honesty is the best policy, even in the face of mistrust and disinterest. Candid communication of information about the company, its business outlook, and projected changes can help ensure the acceptance of its policies and principles.

7. Management should establish a working rapport with union officers and recognize the natural leadership they frequently display. Mutual respect should be reflected in efficient administration of all matters concerning management and the union.

8. A realistic effort should always be made to avoid either overantagonism or overcooperation. Either can be self-defeating and lead to an erosion of rights. Mature judgment is a must in preventing hasty or illconsidered decisions by union or management

9. Management must manage. It can and should be fair and just in all its labor relations, but it should live up to all obligations and expect the union to do the same. A contract should never be a club for either to wield, but rather an agreement to be respected and obeyed.6

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND THE LAW

Like other employers, broadcasters are required to comply with a large number of laws dealing with the hiring and treatment of employees. Among the most important federal laws are the following:

• Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, makes it unlawful for an employer to discriminate in hiring, firing, compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

• Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, as amended, forbids employers with 20 or more employees from discriminating against persons 40 years of age or older with respect to any term, condition, or privilege of employment, including, but not limited to, hiring, firing, promotion, layoff, compensation, benefits, job assignments, and training.

• Equal Pay Act of 1963, as amended, prohibits wage discrimination between male and female employees when the work requires substantially equal skill, effort, and responsibility, and is performed under similar working conditions.

• Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, an amendment to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, forbids discrimination based on pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions. The act seeks to guarantee that women affected by pregnancy or related conditions are treated in the same manner as other job applicants or employees with similar abilities or limitations.

• Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 prohibits employers with 15 or more employees from discriminating against qualified individuals with disabilities in job application procedures, hiring, firing, advancement, compensation, job training, and other terms, conditions, and privileges of employment. Individuals are considered to have a “disability” if they have a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, have a record of such an impairment, or are regarded as having such an impairment.7

• Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 requires employers with 50 or more employees to make available to qualified employees (i.e., those who have been employed for at least 12 months) up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave during any 12-month period for one or more of the following reasons: for the birth and care of the newborn child of the employee; for placement with the employee of a son or daughter for adoption or foster care; to care for an immediate family member (spouse, child, or parent) with a serious health condition; or to take medical leave when the employee is unable to work because of a serious health condition. Upon return from leave, employees must be restored to their original job, or to an equivalent job with equivalent pay, benefits, and other employment terms and conditions.

Equal Employment Opportunity

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is primarily responsible for ensuring compliance with federal laws prohibiting discrimination in employment practices. However, the FCC has enacted equal employment opportunity rules (EEO) to which broadcasters must also adhere.8

The rules require that broadcast stations afford equal opportunity in employment to all qualified persons and refrain from discriminating on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, and sex. Religious broadcasters may establish religious beliefs or affiliations as a job qualification for all station employees. However, they may not discriminate in any of the above areas among those who share their beliefs. Stations also must establish, maintain, and carry out a positive continuing program of specific practices designed to ensure equal opportunity and nondiscrimination in every aspect of station employment policy and practice. Under the terms of its program, a station must

• define the responsibility of each level of management to ensure vigorous enforcement of its policy of equal opportunity, and establish a procedure to review and control managerial and supervisory performance

• inform its employees and recognized employee organizations of the equal employment opportunity policy and program and enlist their cooperation

• communicate its equal employment opportunity policy and program and its employment needs to sources of qualified applicants without regard to race, color, religion, national origin, or sex, and solicit their recruitment assistance on a continuing basis

• conduct a continuing program to exclude all unlawful forms of prejudice or discrimination based upon race, color, religion, national origin, or sex from its personnel policies and practices and working conditions

• conduct a continuing review of job structure and employment practices and adopt positive recruitment, job design, and other measures needed to ensure genuine equality of opportunity to participate fully in all organizational units, occupations, and levels of responsibility9

In carrying out their equal employment opportunity program, licensees with five or more full-time employees (those who work at least 30 hours per week), must

• recruit for every full-time vacancy

• use recruitment sources to ensure wide dissemination of the vacancy

• notify organizations involved in assisting job seekers, if those organizations request notification

• engage in recruitment initiatives that go beyond efforts to fill specific vacancies. The goal is to reach persons who may not be aware of opportunities in the broadcasting industry or who may not yet have the experience to compete for current vacancies. Station employment units (i.e., a single station or multiple station cluster in a local market) with five to ten full-time employees and small market licensees must complete at least two such initiatives in each two-year period. Units with more than ten full-time employees should complete at least four initiatives in the period. Among the sixteen initiatives are hosting, co-sponsoring, or participating in job fairs, establishing an internship program, and participating in job banks and scholarship programs.

• analyze the recruitment program on an ongoing basis to ensure its effectiveness and address any problems identified as a result of the analysis

• analyze periodically measures taken to implement the equal employment opportunity program

• retain records to document satisfaction of the recruitment and initiative requirements10

Licensees with fewer than five full-time employees must comply only with the nondiscrimination requirements.

The FCC uses three documents to monitor compliance with its EEO rules:

1. An annual EEO public inspection file report, which describes the licensee’s EEO efforts during the preceding year. The file report must include the following information:

• a list of all full-time vacancies filled by the station’s employment unit during the preceding year, identified by job title

• for each such vacancy, the recruitment sources used to fill the vacancy identified by name, address, contact person, and telephone number. Organizations that have asked to be notified of job vacancies must be identified separately.

• the recruitment source that referred the hiree for each full-time vacancy during the preceding year

• data reflecting the total number of persons interviewed for fulltime vacancies during the preceding year and the total number of interviewees referred by each recruitment source used in connection with such vacancies

• a list and brief description of initiatives undertaken in the preceding year11

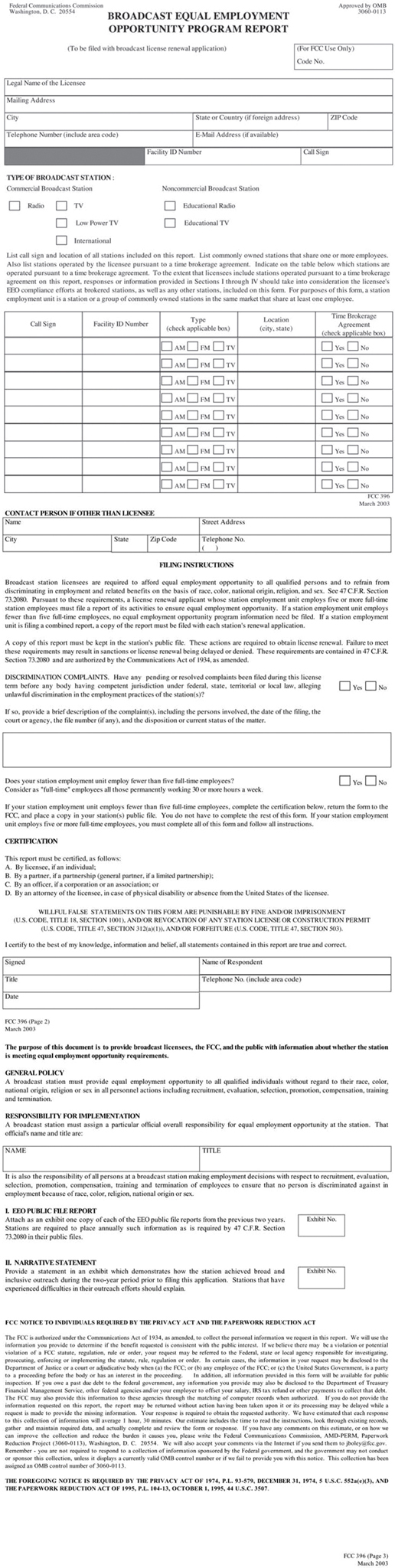

2. An EEO Program Report, FCC Form 396 (Figure 3.2), which is filed with the station’s application for license renewal. The report asks for information on the licensee, contact person (if other than the licensee), and any pending or resolved discrimination complaints.

Figure 3.2 Broadcast Equal Employment Opportunity Program Report (FCC 396).

• Stations with fewer than five full-time employees complete only the first two pages of the form. Those with five or more also must complete page three, which requests

• the name and title of the station official responsible for the EEO program

• the submission of two attachments. One is a copy of the EEO public file reports from the previous two years. The second is a narrative statement demonstrating how the station achieved “broad and inclusive outreach” in the two-year period prior to the filing of the renewal application.

3. A Broadcast Mid-Term Report, FCC Form 397. The report is filed four years after a station’s application for license renewal. The public inspection file reports for the preceding two years are submitted as attachments.

• The FCC may conduct inquiries of licensees at random or if it has evidence of a possible violation of its EEO rules. In addition, it completes random audits of about 5 percent of radio and television licensees each year.

• Managers can take steps to avoid problems that might result from an inquiry or audit. At the least, they should

• demonstrate serious attempts to comply with the rules

• ensure that all station employees involved in the recruitment and hiring processes are familiar with the rules and adhere to them

• keep current all information relating to the recruitment and initiative requirements

• maintain records sufficient to verify the accuracy of information provided in the EEO public file reports, Form 396, and Form 397

Sexual Harassment

One form of discrimination to which managers are paying more attention today is sex discrimination resulting from sexual harassment in the workplace.

Pressure to treat the issue seriously was reinforced by four Supreme Court decisions during the 1990s. In 1993, the court agreed unanimously that employers can be forced to pay monetary damages even when employees suffer no psychological harm. In 1998, in another unanimous ruling, it determined for the first time that unlawful sexual harassment in the workplace extends to incidents involving employees of the same sex.

Later in the year, in two 7-2 decisions, justices held that an employee who resists a superior’s advances need not have suffered a tangible job detriment in order to pursue a lawsuit against an employer. But the court said such a suit cannot succeed if the employer has an antiharassment policy with an effective complaint procedure in place and the employee unreasonably fails to use it.

In the two latter decisions, the court established that

• employers are responsible for harassment engaged in by their supervisory employees

• when the harassment results in “a tangible employment action, such as discharge, demotion, or undesirable reassignment,” the employer’s liability is absolute

• when there has been no tangible action, an employer can defend itself if it can prove (1) that it has taken “reasonable care to prevent and correct promptly any sexually harassing behavior,” such as by adopting an effective policy with a complaint procedure, (2) that the employee “unreasonably failed to take advantage of any preventive or corrective opportunities” provided

Harassment may take many forms. Under guidelines issued by the EEOC, unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when (1) submission to such conduct is made either explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment, (2) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting such individual, or (3) such conduct has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.12

The licensee is held responsible for acts of sexual harassment committed by its “agents” and supervisory employees, even if it has forbidden them. If the conduct takes place between fellow employees, again, the licensee is responsible when it knew, or should have known, of the conduct, unless it can show that it took immediate and appropriate corrective action.13

To guard against the employee absenteeism and turnover that often accompany sexual harassment, the adverse impact on productivity and morale, and the filing of charges and lawsuits, managers should take the following actions:

1. Develop a written policy that defines sexual harassment and states explicitly that it is a violation of law.

2. Make sure that all employees are aware of the policy and understand it.

3. Train employees, especially supervisory personnel, to recognize harassment so that they may take action if they suspect it and, thus, prevent potentially more serious consequences if the behavior goes unchecked.

4. Establish a procedure that encourages victims to come forward and assures them that their complaints will be handled promptly and professionally.

5. Investigate all complaints immediately and thoroughly and advise the parties of the outcome, even if the allegations are not substantiated.

6. Document all complaints and their disposition. Complete records will be useful if legal action is initiated.

Computer Use

Productivity loss and the potential for sexual harassment and other lawsuits also may result from unrestricted employee use of station computers. To guard against such eventualities, some companies have installed software tools to monitor individual computer activity. The expectation is that staff members will be wary of spending large amounts of time on personal E-mail or Web surfing if they know that checks may be made on how they spend their “working” hours.

Of no less concern to managers is the fear that employee-originated E-mail or online chat room messages or the downloading of some Internet content may expose the station to an array of lawsuits. In addition to sexual harassment, the risks include defamation, discrimination, the dissemination of trade secrets, and copyright and trademark infringement.

Stations that reject monitoring because of its “big brother” aura may opt for filtering software to limit access to the Internet. However, that will not necessarily remove the possibility of inappropriate E-mail or chat room activity and legal liability.

Managers are advised to develop and enforce an “acceptable use policy” (AUP) for computers. The following are among the provisions that should be considered for inclusion:

• computers, software, and Internet and E-mail accounts are the property of the company and should be used for business purposes only

• Internet and E-mail accounts cannot be used for an employee’s personal interests

• downloading copyrighted software is prohibited

• accessing or sending sexually explicit material is forbidden

• participation in any online chat room or discussion group must be approved in advance and must not include statements about the company or its competitors

• email cannot be used to communicate trade secrets or other confidential information without prior written permission

• encryption is required for sensitive E-mail messages and accompanying files

• sending offensive or improper messages, such as those involving racial or sexual slurs or jokes, is prohibited

• employee access to a coworker’s E-mail files must be authorized in advance

• email messages and Internet activity will be monitored from time to time by the employer

• violation of the policy will result in disciplinary action, up to and including dismissal

In time, other problems may arise and require modifications or additions to the AUP.

To ensure that all staff members are familiar with the policy, a copy should be placed in the employee handbook. However, given the potential gravity of abuse of the company’s computers, it may be advisable to conduct a training session on appropriate use and to require employees to sign an acknowledgment that they have received and understand the policy.

WHAT’S AHEAD?

Many challenges confront staff members who are responsible for human resource management. Among the most important are those posed by an increasingly diverse workforce and changing employee values.

Today’s workforce is the most diverse in American history. The first wave of baby boomers, most of them white and male, is retiring but is not being replaced by employees of like color and gender. In fact, white males comprise a much smaller percentage of new hires than in earlier years.

Women now constitute the majority of new job entrants. Some are recent school or college graduates. Other are older and are re-entering the job market after an absence of some years to raise children.

Many new employees are members of minority groups, chiefly African American and Hispanic and, in some parts of the country, Asian. According to some estimates, by 2010 almost half of the nation’s new workers will be people traditionally classified as minorities. Many will be first-generation immigrants, and almost two-thirds of them will be women.14

Managing diversity will not be easy for those who are unprepared for it. Nonetheless, managers must recognize and respond to this new reality in their recruiting, selection, orientation, and training activities.

If they are to succeed, they must demonstrate an understanding of, and sensitivity to, the varied backgrounds, experiences, and ambitions of new staff and strive to ensure that other employees demonstrate similar traits.