2

Financial Management

This chapter reviews the increasingly important area of financial management and examines

• the two major forms of financial statements used in the industry

• basic accounting terminology employed by electronic media managers

• methods used to produce good financial performance and to monitor financial progress

For years, electronic media education has focused on the operating skills thought to be necessary for a successful career in the industry. Traditionally, the major topics studied have been sales, programming, production, and management. Massive changes triggered by the deregulatory climate of the 1980s catapulted another subject to prominence in the curriculum. That subject is financial management.

Deregulation brought financial speculators into the electronic media business. The prevailing wisdom of the mid-to-late 1980s was the “greater fool” theory. Under this concept, money was made by selling a broadcast license or cable franchise to another at a profit. Operational performance was deemphasized in favor of appreciation potential.

All that changed around 1989. Prices had risen to the point that operations could no longer retire the massive debt run up by speculators. Numerous electronic media companies went into default, and prices dropped.

By the early 1990s, broadcast stations and many cable systems were valued on a multiple of the cash flow they generate. Operational financial performance was the new coin of the realm.

Then, in 1996, everything changed again with the passage of the Telecommunications Act. Gone were the national ownership limits on radio. Those for television were relaxed. In-market ownership combinations of up to eight radio stations were permitted, depending on market size.

The adoption of the new law set off another round of speculative buying and consolidation, almost without regard to financial performance.

The radio consolidation was largely completed by late 2001. Today, operators are returning to the basics of producing operating results and return on investments for public and private investors. Clearly, into the new century, operational financial performance is to be the coin of the realm once again.

This switch has been prompted by the fact that, by the middle of 2004, the post-1996 consolidated operators were receiving negative reviews from financial analysts and were being characterized as market underperformers. Now, more than ever, management personnel must be well versed in understanding and achieving financial results.1

Pressure to acquire basic financing and accounting knowledge is coming from other sources, too. In the technology-driven decade of the 1990s, lines of distinction between traditional forms of electronic media became blurred or nonexistent. This development spawned a need for a new breed of communication manager—one with both a traditional background and basic accounting and financial skills.2 As the industry has progressed since the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the financial management element of the managerial equation has assumed even greater significance. Today’s manager is concerned more about sales and making and meeting budget forecasts, and less about programming.

It is not possible in the pages of this chapter to make anyone a financial expert. The goal here is to acquaint the reader with financial terms and concepts and with the typical financial reports used. It is recommended strongly that today’s electronic media student pursue a more detailed examination of these matters through finance and accounting courses.

THE ACCOUNTING FUNCTION

The accounting function in the electronic media is performed using specialized computer software developed by various companies. The leading television traffic and accounting systems are provided by Columbine. Radio software companies include Computer Concepts and Wicks Broadcast Solutions/CBSI. Some of these systems are integrated or interfaced with digital audio systems. Examples include Digilink by Arrakis and Audio Vault by Broadcast Electronics.

Even with computerized systems, mistakes often are made. Ad agencies report that there is a 70 to 80 percent discrepancy between invoices and what actually aired.3 As a result, stations and agencies are moving to a new form of electronic invoicing—electronic data interchange (EDI). As of this writing, 50 to 90 percent of stations use EDI in some form. Traffic system vendors are testing such systems. Eventually, paper orders will be eliminated.4

Whether computerized or manual, certain accounting concepts and terminology are basic. Any person with serious management ambition must master them.

Effective financial management requires detailed planning and control. Planning expresses in dollar terms the plans and objectives of the enterprise. Control involves the comparison of projected and actual revenues and expenses. The basic planning and control mechanism is the budget.

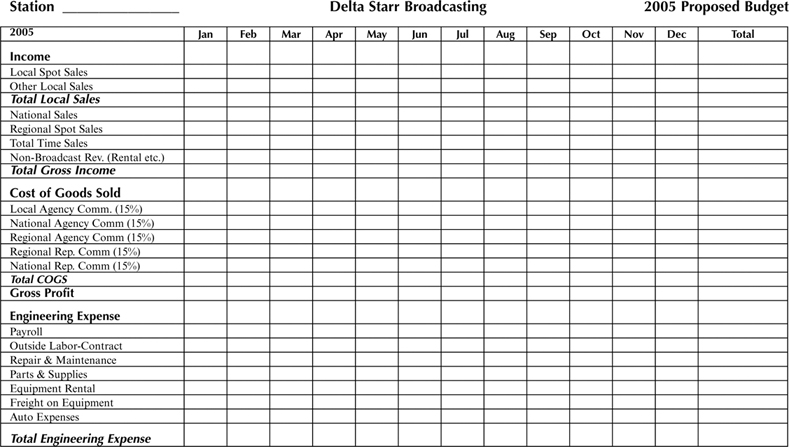

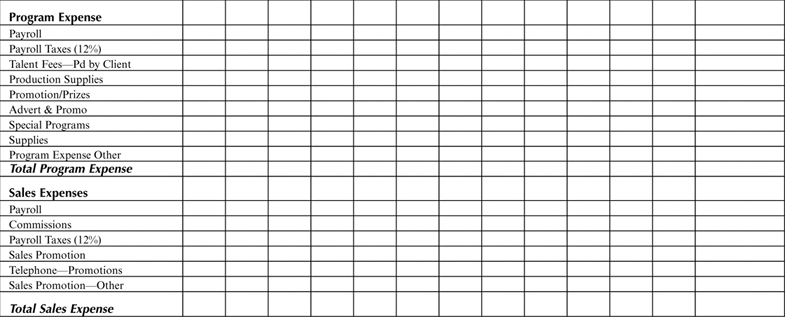

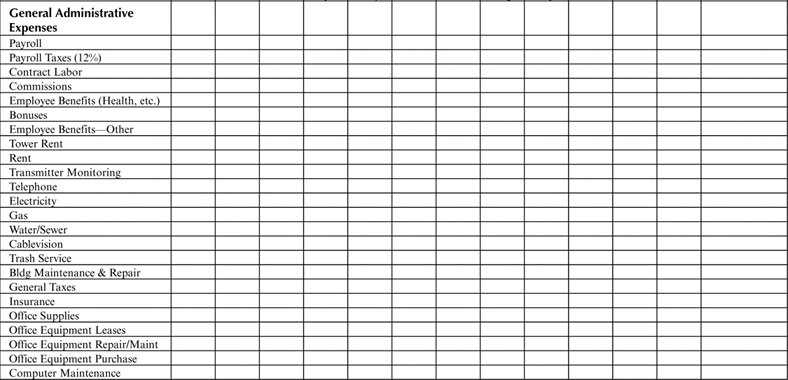

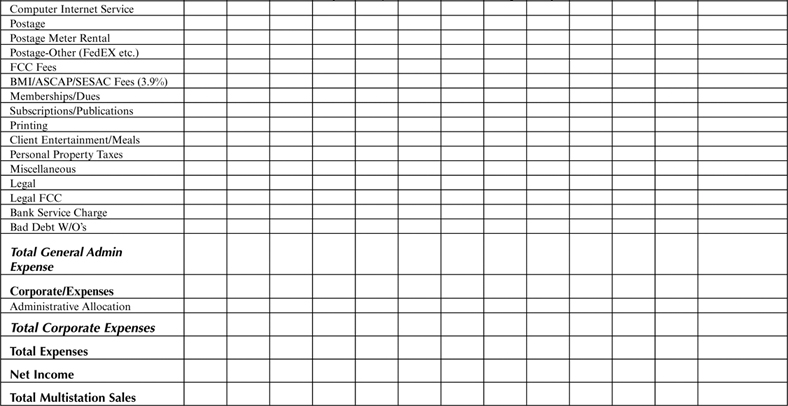

To prepare the budget, management collects from department heads financial data and reviews and edits them. Most stations and systems use a form to display the information for the budget period, usually one year. Figure 2.1 is a 12-month calendar summary form employed by a radio multiple-station operator in an annual budget preparation.

Figure 2.1 Budget worksheet used by a multiple radio station operator.

Budgeting deals with the future. However, past experience suggests realistic revenue and expense amounts. Generally, a reserve account is maintained to cover emergencies. During the year, regular budget reports permit the general manager to compare planned and actual results and to make necessary adjustments.

Budgeting and cost controls, together with financial forecasting and planning, are among the major responsibilities of the business department. Other responsibilities include banking, billings to and collections from advertisers and advertising agencies, payroll administration, processing of insurance claims, tax payments, purchasing, and payments for services used.

Fundamental to the efficient discharge of the accounting function are the establishment and maintenance of an effective and informative accounting system that will protect assets and provide financial information for decisionmaking and the preparation of financial statements and tax returns. Such a system is based on financial records. As noted above, most such records are produced for electronic media concerns via specialized computer software.

Planning Financial Records

No matter what the electronic media business is—radio, television, cable, or other—management requires certain basic information to function. It includes amounts and sources of revenues and expenditures, and levels of operational profitability on a monthly and annual basis.

Cable system operators are concerned about their main revenue source, subscribers, while broadcasters want details of advertising sales. On the expenditure side, both cable and broadcast managers require information on programming costs. Cable operators need figures on pole rent and contract labor. Broadcasters care about the cost of maintaining the transmission plant.

Whatever the particular need, the quest for management financial information must begin with the design of a recordkeeping system that will produce the desired results. Every manager embarking on the task of setting up financial records is looking for guidance (i.e., What is a good model? or What has worked well for others?). Fortunately, excellent materials are available on records planning.

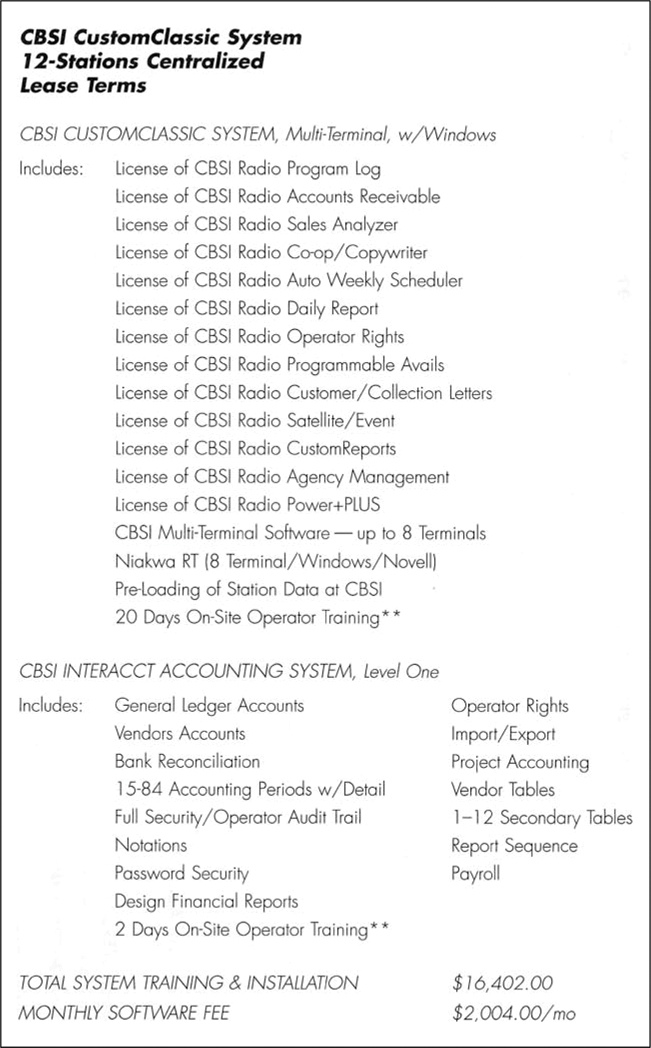

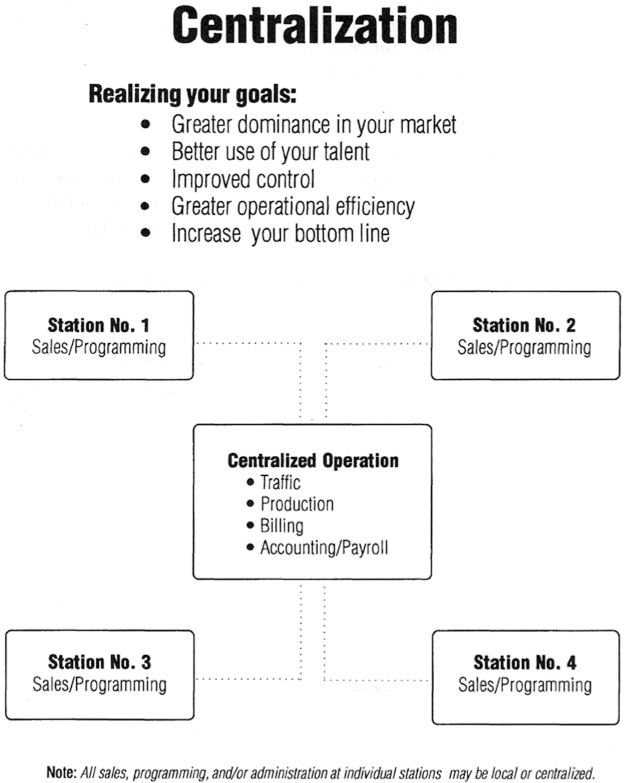

The principal sources utilized to set up accounting records are software companies that design and customize traffic and accounting systems for single and multiple station operators. Figure 2.2 presents a proposal submitted to a multiple station radio operator for such a system. You will note that the proposal provides for the design and implementation of financial reports. Figure 2.3 depicts how a centralized traffic and accounting system might be configured.

Figure 2.2 Vendor proposal to design and install a traffic and accounting system for a group radio operation.

Figure 2.3 Proposal for a multistation centralized traffic and accounting system.

Another source is the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), which has published an accounting manual for radio stations.5 Included are chapters on financial statements, accounting records, charts of accounts with explanations, and accounting system automation.

Still another source of information is the Broadcast Cable Financial Management Association (BCFM). This organization, composed of industry members, concentrates on financial questions of import to its membership. It, too, publishes an accounting manual.6 The contents are principally detailed charts of accounts with explanations, and model financial statement forms.

Whether the system chosen is manual or computerized, it must be designed to deliver to management certain basic information and to render financial reports. It will consist of a number of journals and ledgers that record and summarize all financial transactions and events.

The records most commonly generated are the following:

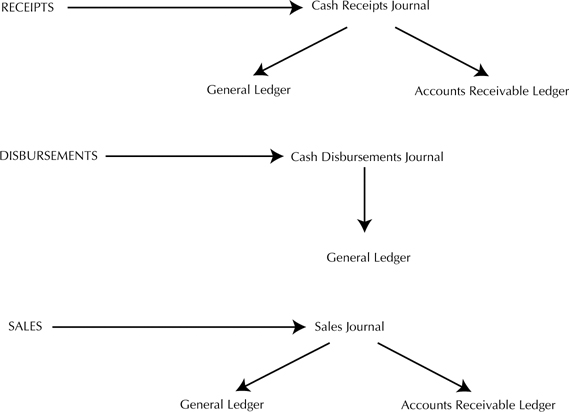

• Cash receipts journal shows all monies received, listed by revenue account number. It identifies the payer and—in the case of receipts for advertising—gross amounts, discounts, and agency commissions, and resulting net amounts. Journal entries cover a given period of time, at the end of which all amounts are totaled and posted to the general ledger. Individual client payments are credited to the appropriate account in the accounts receivable ledger (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Financial recordkeeping process.

• Cash disbursements journal records all monies paid out. Often, it is organized by major expense category and account number and lists the check number, date, amount, and the company or person to whom payment was made. Totals are posted to the general ledger (Figure 2.4).

• Sales journal lists all transactions after the commercial schedule has run and has been billed to the client. No entries are recorded until this happens. Entries are triggered by performance against the contract and not when the contract is signed. When made, sales journal entries include the client’s name, invoice number, date, amount, and the name of the staff member who made the sale. If part of the cost results from the sale of talent or program materials and facilities, that information is entered. So, too, are details of tradeouts—the exchange of advertising time for goods or services. Entries for a given period are totaled and posted to the general ledger. Each gross billing figure is entered on the client’s page in the accounts receivable ledger (Figure 2.4).

• General journal includes noncash transactions and adjustments, such as depreciation and amortization, and accrued bills not yet paid.

• Accounts receivable ledger records money owed to the business by account. Using the ledger, the station or system prepares an aging sheet showing accounts that are current and those that are delinquent.

• Accounts payable ledger lists monies owed by the business and includes the name of the creditor, invoice date and amount, and the account to be charged.

• General ledger is the basic accounts book. It contains all transactions, posted from various journals of original entry to the appropriate account. The general ledger consists of two sections. One records figures for assets, liabilities, and capital, and the other the income and expense account figures.

Information from the general ledger is used to prepare two major financial records, the balance sheet and the income statement.

Balance Sheet

The balance sheet is a statement of the financial position of the station or system at a given time. It comprises three parts:

• assets, or the value of what is owned

• liabilities, or what is owed

• net worth or equity, or the financial interest of the enterprise’s ownership

The term balance sheet is derived from the fact that total assets should equal total liabilities plus net worth or equity. The two sides of the sheet are, therefore, in balance.

Assets

Assets are classified as follows:

• Current assets are those assets expected to be sold, used, or converted into cash within one year. They typically include cash, marketable securities, notes, accounts receivable, inventories (including programming), and prepaid expenses.

• Fixed assets are those assets that will be held or used for a long term, meaning more than one year. Land and improvements (e.g., a parking lot), buildings, the transmitter, tower, satellite uplinks and downlinks, antenna system, studio and mobile equipment, vehicles, office and studio furniture, and fixtures are among items considered fixed assets.

• Fixed assets are tangible assets—things. They depreciate, which means that use over time reduces their value. Depreciation is a business expense. The amount of time over which a tangible asset may be reduced systematically in value is determined by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) guidelines. A more detailed discussion of depreciation occurs later in this chapter.

• Other assets is a category that includes mainly intangible assets—those having no physical substance. Examples are the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) license, organization costs, and goodwill. These assets are amortized, or written off, for financial statement reporting purposes.

• Amortization, or write-off, of the goodwill amount means that the total amount is systematically reduced over a period of time by charging equal annual amounts to the profit and loss statement. Goodwill primarily represents the value of the broadcast license or cable franchise. For example, if a station were purchased for $6 million, and the value of its tangible assets were $3 million, then the goodwill amount would be $3 million. That amount would be charged to the station profit and loss account in equal annual amounts. For reasons discussed later in , “Entry into the Electronic Media Business,” some intangible amounts, while deducted for financial statement reporting purposes, cannot be deducted for tax purposes.

• An additional example of other assets is the network affiliation agreement of most television stations. In the mid-1980s, some stations began for tax purposes to write-off these agreements. However, such attempts occasioned significant IRS controversy and litigation. Most of these disputes were resolved by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993. The act provided that certain intangible or other assets could be amortized over a 15-year period. Under the law, examples of permitted deductions are government licenses and permits, noncompete agreements, network affiliation agreements, franchises, trademarks, trade names, and goodwill. In the situation cited above, the acquired station’s goodwill of $3 million would be amortized for tax purposes over 15 years, at the rate of $200,000 per year.

• Prepaid and deferred charges include all prepayments made. Insurance, taxes, and rents are examples.

Liabilities

Liabilities reflect short- and long-term debts. They are listed as follows:

• Current liabilities include accounts, taxes, and commissions payable. Monies owed for supplies, real estate, personal property, social security and withholding taxes, music license fees, and sales commissions fall into this category. Current liabilities also include amounts due on program contracts payable within one year.

• Long-term liabilities include those liabilities not expected to be paid within one year. Examples of such liabilities are bank debt, mortgages, and amounts due on program contracts beyond one year.

Net Worth

Net worth, or equity, records ownership’s initial investment in the broadcast station or cable system, as increased by profits generated or reduced by losses suffered.

Preparing Financial Statements

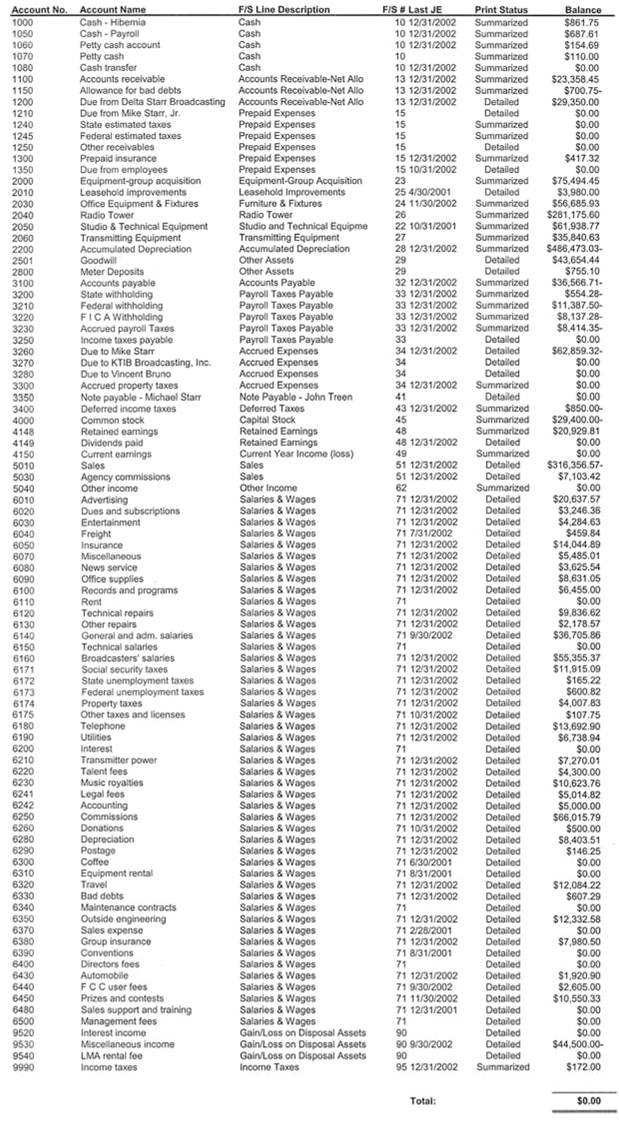

Financial statement preparation begins with a chart of accounts, a list of account classifications. Each account is assigned a number.

The following balance sheet chart of accounts is used by LaTerr Broadcasting Corporation, licensee of KTIB-AM, Thibodaux, Louisiana (Figure 2.5). Asset accounts are numbered 1000 to 2800, 5010 to 5040, and 9520 to 9540. Liability accounts are 3100 to 3400, 6010 to 6500, and 9990. Equity accounts are 4000 to 4150.

Figure 2.5 Balance sheet chart of accounts.

(Source: LaTerr Broadcasting Corporation. Used with permission.)

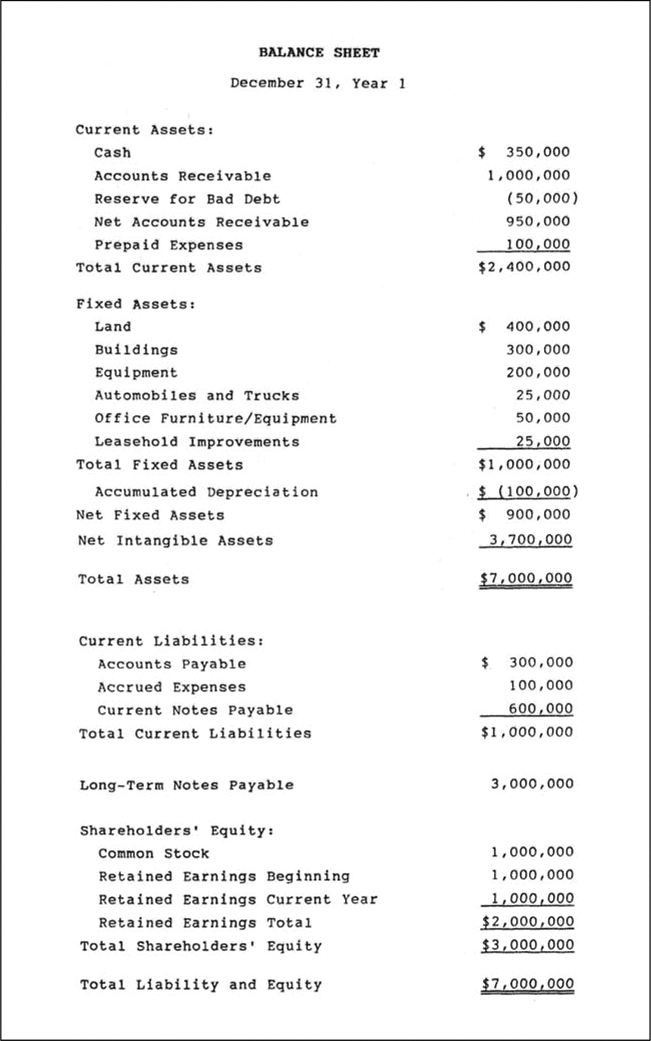

It is from records of the kind detailed here that the balance sheet is prepared (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 Example of a broadcast station’s balance sheet.

The financial health of a company is often judged by examining two ratios computed from the balance sheet numbers. The first of these is current ratio, which is obtained by dividing total current liabilities into total current assets. A good current ratio is 1.5 to 1. The second is the debt-to-equity ratio. It is computed by dividing stockholders’ equity by long-term debt. A satisfactory debt-to-equity ratio is considered to be 1 to 1.

Income Statement

The income statement also is known as the operating or profit and loss (P and L) statement. It summarizes financial transactions and events over a given period of time. The difference between revenues and expenses is the profit or loss for that period.

Revenues

A major source of revenue for all broadcast stations is the sale of time to local, regional, and national advertisers. Network compensation may be an additional source for network-affiliated television stations and some radio stations. Another source is Non-Traditional Revenue (NTR) (see Chapter 5, “Broadcast Sales). Other broadcast revenues include the sale of programs and talent and the rental of station facilities. Rents received for the use of station-owned towers or land, and interest and dividends are examples of nonbroadcast revenues.

Revenue sources for cable systems are somewhat different. Most revenue is derived from subscribers. However, systems are developing their advertising revenue through the sale of local and national spots, principally in local availabilities in advertiser-supported networks. Pay-per-view (PPV), video-on-demand (VOD), high-speed Internet, telephone, and music channels are among significant growth areas. Cable operators are required by law to set aside channel capacity for lease to third parties, and some receive revenue from such leases.

Expenses

Expenses are classified either as direct or as operating and other. Direct expenses are commissions paid to agencies for the sale of time. Operating and other expenses are listed according to the organizational structure. Usually, they reflect the costs of operating the major departments or areas of activity. In broadcast stations, they are technical (engineering), program, sales, promotion, news, and general and administrative.

Other expenses are cash and noncash expenses incurred in the operation of the business. Depreciation is an example of a noncash expense and results from the write-off of tangible assets, such as plant and equipment. Typically, the asset is reduced by equal annual amounts over its life. The systematic annual reduction in the asset’s value is an expense and is charged to the income statement.

U.S. tax laws divide tangible assets into useful life categories for purposes of calculating depreciation. For example, buildings have a useful life of 41 years and towers a useful life of 15 years. Other noncash expenses may be amortized, the systematic reduction of an account over a period of time. As noted earlier, an example of an expense that is amortized is goodwill.

The term amortization also is frequently applied to program contracts, which are a cash expense item. Various methods for amortizing program contracts exist. One method is straight line, which permits a deduction of the total contract in equal annual amounts over the term of the contract. The alternate approach is called accelerated amortization. Under this method, larger amounts are written off in the early years of a contract, the theory being that the initial runs of a program have the most value. More detail on the specifics of these two approaches can be found in industry publications such as BCFM’s Broadcast Accounting Guidelines. It should be noted that amortized program contracts are tax deductible and are usually charged to the program expense account, not to the “other” category.

Another common “other” expense is interest. Interest is the premium paid on amounts borrowed to finance acquisitions, purchases of equipment, or construction of a new facility.

Expenses are charged to the department incurring them. Those that are necessary for the overall functioning of the operation, such as utilities, generally are counted against general and administrative costs. Salaries and wages represent an expense in all departments. The following are examples of other broadcast department expenses:

Technical

• parts and supplies for equipment maintenance and repair

• rental of transmitter lines

• tubes for transmitter and studio equipment

Program

• program purchases

• rights to broadcast events (e.g., sports)

• music licensing fees

• supplies (e.g., tapes)

• line charges for remote broadcasts

Sales

• commissions paid to staff

• commissions paid to station rep company

• trade advertising

• audience measurement

• travel and entertainment

Promotion

• sales promotion

• advertising and promotion of programs

• research

• merchandising

News

• videotape

• recordings, tapes, and transcripts

• raw film

• wire service

• photo supplies

• art supplies

General and Administrative

• maintenance and repair of buildings and office equipment

• utilities

• rents

• taxes and insurance

• professional services (e.g., legal, accounting)

• office supplies, postage, telephone, and telegraph

• operation of station-owned vehicles

• subscriptions and dues

• contributions and donations

• travel and entertainment

Operating expenses are deducted from revenue to determine profit or loss. Profit is the amount by which revenue exceeds expenses. The profit resulting from the deduction of operating expenses from revenue is called operating profit. Such deductions do not include noncash expenses, such as the depreciation and amortization previously discussed. Once the operating profit has been determined, it is then further reduced by depreciation, amortization, and federal, state, and local taxes. Operating profit adjusted for other expenses and taxes is called net profit.

To operate effectively, electronic media managers must know how much cash their enterprise produces annually, not just how much profit. Cash flow is the term used to describe the cash generated. It is calculated by adding back to net profit the amounts charged to expenses for depreciation, amortization, interest, and taxes. It is the term cash flow that is used to determine the value of an electronic media property by applying multiples to it. For a more detailed treatment of these concepts, refer to the discussion of multiples and prices in , “Entry into the Electronic Media Business.”

No income statement treatment can be complete without a discussion of trade-outs. A trade-out or barter transaction occurs when goods or services are provided in exchange for time. As direct transactions, they do not produce commissionable billings for advertising agencies and, depending upon individual station or system policy, may not result in commissions for account executives either. The transactions must be included on financial statements, with the major questions being the value to assign to them and when to record them.

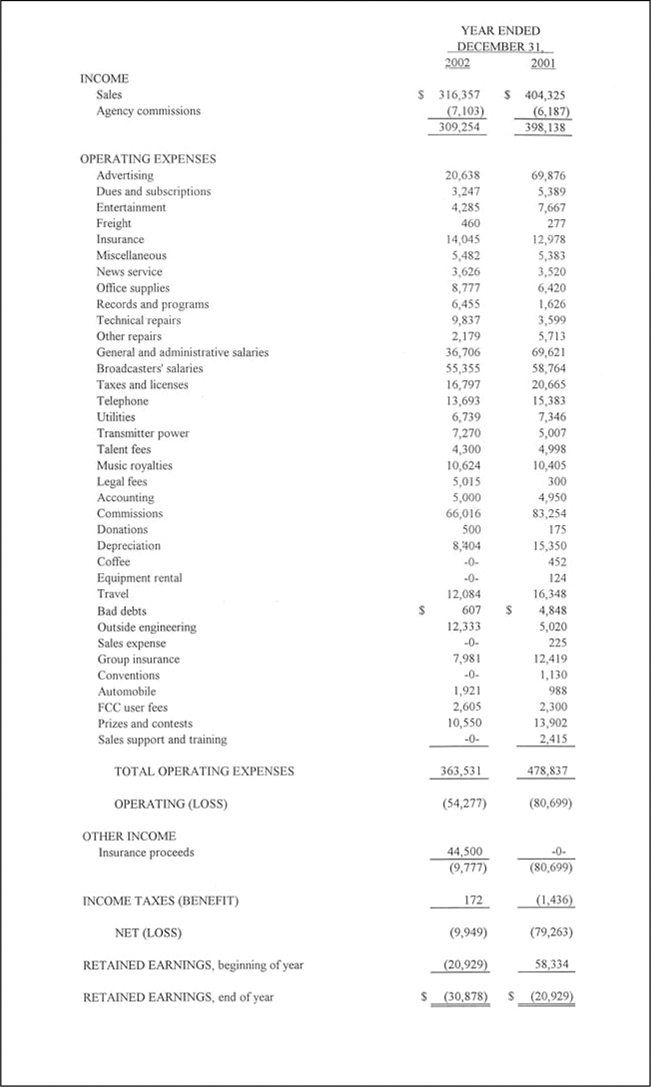

The Broadcast Cable Financial Management Association recommends that the value of the transaction be equal to the cash saved as a result of the barter. On timing, the BCFM outlines three ways: (1) record income and expense in the same amount in the same period; (2) record income and expense in equal amounts over the term of the barter contract; or (3) record revenue as trade spots are run and expense as goods and services are used. One of these three methods must be selected and consistently applied. Figure 2.7 is an example of an income statement.

Figure 2.7 Broadcast station income statement.

(Source: LaTerr Broadcasting Corporation. Used with permission.)

Different proportions of revenue are provided by each source to radio and television stations, and radio and television stations incur expenses differently. Regrettably, it is no longer possible to compare the specific revenue and expense differences between the two media. That is because the National Association of Broadcasters discontinued its Radio Financial Report in 1992. And, in the post-1996 environment, it is unlikely that the major consolidators will be willing to divulge financial information that could lead to a resurrected report.

The NAB continues to collect and report TV industry financial data. The 2004 report showed that local advertising accounted for more than 60 percent of gross advertising revenues for a typical affiliate of ABC, CBS, and NBC.7 The biggest expense items for those stations were news (29.1 percent) and programming (20 percent).8

COST CONTROLS

Radio, television, and cable have discovered the importance of cost controls comparatively recently. For most of their history, all three enjoyed almost automatic and sizable annual revenue increases. In that climate, management increased profits primarily through such increases, not through reducing costs.

In the late 1980s, the equation changed for broadcast radio and television. The combination of general economic conditions, the rise of niche marketing due to cable, and the fragmentation of audience shares related to the FCC’s liberal licensing policies all but eliminated the customary annual sales increases.

That tide was reversed with a booming economy in 1993 and has continued. Radio has increased its overall share of mass media advertising. Television is still growing in sales volume, but at a lower annual percentage than radio. Cable progress has been impacted by the emergence of DBS as a competitor. Cable rate regulation expired in 1999 under the terms of the 1996 Telecommunications Act. However, continued subscriber rate increases have caused Congress to contemplate possible reconsideration of that provision. Now that it passes 97 percent of the nation’s 109 million TV households, cable must look to rate increases, new services, and advertising for revenue growth.

In the new environment, albeit at different times, radio, television, and cable turned to cost controls. The most effective control technique capable of producing significant immediate results is personnel reduction. The 1996 act permitted expanded ownership consolidation, especially in local radio. That development has occasioned extensive reduction. Radio and television eagerly seized on this method, occasionally producing headlines with it. Increasing reliance on sophisticated automation for television, and automation plus utilization of satellite formats for radio, accelerated staff cutbacks.

When cable’s moment of truth came, it focused initially on personnel adjustments, too. Cable also relied on automation technology to achieve some of its personnel goals. In addition, it turned to outside contractors to perform some of the functions formerly undertaken by staff. Cable uses independent contractors for installation, rebuilds, and other technical duties and, in some instances, for the sale of local and spot advertising.

Once the immediate cost benefits of personnel reduction are realized, additional expense reduction is a lot more tedious and requires persistent management attention. Continuing vigilance and monitoring of certain expenditure categories historically have led to savings. Many of these items involve commonsense administration and are common to radio, television, and cable. They include the following:

1. Employee Performance

A. Employees should be hired on the basis of their qualifications to carry out required tasks. If a staff member lacks the necessary skills, or has to be trained or assisted, performance will suffer and the station or system will not be receiving value for its salary or wage dollar.

B. Each employee’s workload should be great enough to justify the position. Underemployment represents a waste of dollars and a drain on profits.

C. Employee efficiency is influenced by available resources. The company must provide the equipment and the space necessary to enable staff to produce quality work efficiently and economically.

D. The work environment must be conducive to productivity. Uncomfortable temperatures, noise, and interruptions detract from work, and may reduce accomplishments and profits.

E. Supervisory personnel should be conversant with the job description of each employee in their charge and, through example and direction, strive to ensure that each performs at maximum efficiency.

F. Clear policies should be established and enforced on employee working hours and privileges, such as the frequency and length of coffee or meal breaks. Abuse can result in lowered productivity. Similarly, policies should be set forth on personal use of the telephone and other facilities. An employee engaged in a personal telephone call or in personal use of a copying machine or computer may delay the completion of business. Further, the cost of long-distance telephone calls for personal reasons can be substantial.

G. Morale is an important element in the willingness of employees to assist in controlling costs. For that reason, management should not underestimate the significance of employer–employee relations and of other factors that contribute to morale.

2. Employee Compensation

• Salaries and wages should be fair and competitive in the market. However, care must be taken with increases and overtime.

• It is financially dangerous to lead employees to believe that they will receive automatic, periodic increases, unless that is company policy. Staff accustomed to receiving such increases will feel resentment if increases are not granted or are discontinued. Instead, some employers prefer to grant bonuses, which are not viewed as a right and need not be given automatically or regularly.

• Employees who regularly receive overtime pay regard it as part of their salary. When overtime is reduced or eliminated, they consider it a cut. If work cannot be completed in the normal work day, consideration should be given to adding part-time personnel at the regular rate of pay, thus avoiding the premium rates that have to be paid for overtime.

3. Professional Services

• Some professional services are necessary, but their use should be reviewed periodically and controlled. The services used most by broadcast stations and cable systems are:

A. Accounting and auditing

• The staff bookkeeper should be able to carry out most of the accounting. If not, an accounting firm will have to be used, and at a substantially higher cost. However, such a firm usually is engaged to file tax papers and conduct audits.

B. Legal

• Most stations find it advisable to retain a Washington, DC, attorney who is qualified to practice before the FCC. The attorney provides the station with timely information and advice, and is especially helpful in the preparation of license-renewal papers. The increasing burden and complexity of federal regulation also has led many cable systems to engage Washington counsel. Some systems are trying to minimize the expense by joining with others in a consortium. Engaging a local attorney in addition is not a wise expense for most stations or systems, since most of the help requested concerns the collection of overdue accounts. That is a service that can be rendered more economically by a collection agency.

C. Consulting

• Stations often feel the need for outside advice on programming, news, sales, and promotion. Engaging consultants can be costly. A more economical approach is to try to include such assistance, if possible, among the services of the station rep company.

4. Facilities

A. Land and buildings

• Even though the cost of purchasing land and buildings may be high, it is more advantageous for a station to own than to rent. This is true, particularly, of the land on which cable satellite downlinks or the broadcast transmitter tower and building are located. If the landowner demands an excessive amount of money to renew a lease, management faces a dilemma. It is especially acute for broadcasters, since the license to broadcast is granted on the present tower location. To move would involve costly engineering studies and attorney fees and would require FCC approval.

• Rental of office and studio buildings poses fewer risks. However, it may be difficult or impossible to obtain the owner’s approval to make structural changes aimed at increasing services or improving efficiency.

B. Equipment

• All equipment should be purchased at the best price available and for its contribution to the quality, efficiency, or range of program or other services. If it will generate additional revenues or reduce costs, so much the better. The temptation to buy equipment for “prestige” should be avoided. The same is true of equipment that will not be used regularly. Renting rather than purchasing may make more sense. A similar approach should be taken with telephone equipment and services. They should be sufficient for the business’s needs, but not extravagant.

• Insurance has become a major cost-increase item. Some insurance requirements are mandated by state law. An example is workers’ compensation. Loan agreements with the station’s or system’s lenders may require certain coverage, such as fire, automobile, title, or errors and omissions. Cost efficiencies on some types of insurance may be achievable through state or national broadcast or cable associations.

• The major problem in recent years has been medical insurance. Premiums have escalated dramatically and are a major expense item. Employers constantly monitor such costs and pursue methods designed to limit the significant annual increases. Today, many companies require up to one or two years of service before an employee qualifies for employer-paid (or partially paid) medical insurance. Generally, deductibles have been increased and benefits have been capped or limited to contain costs. Employees have come to expect that medical insurance will be included in their compensation package. How it is administered is a definite morale factor.

6. Bad Debts

• Failure to collect payment for time sold to advertisers is a problem that confronts many stations and a growing number of cable systems. Elimination of the problem is impossible, but it can be reduced through the statement and enforcement of a policy on billing and payment procedures. It may be necessary to terminate delinquent accounts to prevent additional losses and send a message to other advertisers.

7. Budget Control

• Close control should be exercised over all expenditures. For purchases, this can be accomplished through purchase orders that require the general manager’s signature. A control system should exist for other expenditures, including the following:

A. Travel and entertainment

• A policy should be established for employees who incur work-related travel and entertainment costs, not only to control them but also to satisfy the requirements of the Internal Revenue Service. Before reimbursing employees, many companies require submission of an approval voucher signed by a supervisor or the general manager. Usually, it gives the date and purpose of the travel, locations, and details of and receipts for travel, food, accommodation, and other items, such as parking fees, tips, and tolls.

B. Dues

• Management must determine those associations or organizations in which the station or system should hold membership. The NAB or the National Cable Television Association (NCTA) usually are high on the priority list. Affiliation with the state broadcast or cable association and the local chamber of commerce also may be considered advantageous. However, all memberships should be chosen with an eye to the benefits they provide.

• Many companies believe that department heads and others should join appropriate local, state, or national organizations to advance their careers or the employer’s interests. If the company has a policy of paying employee membership fees, it is important that each proposal for membership be considered on the basis of the benefits that will accrue to the individual and the company. If membership contributes little or nothing, monies spent will be wasted.

C. Subscriptions

• Most employers subscribe to selected newspapers, magazines, and journals, and make them available to staff. Publications should be chosen for their contributions to the interests of the employees and the company. Costs can be reduced by eliminating those that are not read or are of marginal interest.

D. Contributions

• All stations and systems confront requests from nonprofit organizations for financial contributions or air time. To control such expenditures, a policy should be implemented that permits the discharge of the “good corporate citizen” role and prevents resentment by those whose requests cannot be granted. Many companies put a dollar value on each public service announcement aired and mail an invoice to the organization indicating that the amount represents a contribution. Such records also provide useful documentation for license- or franchise-renewal purposes.

E. Communications

• Broadcasting and cable always have been the home of deadlines and time demands. With today’s emphasis on productivity and lean staffs, time pressures are intensified. Such an atmosphere produces an employee reliance on expedited means of communication, which almost always add to costs. Dependence on telephone, fax, photocopies, and express delivery services have become the rule, not the exception. Experienced management knows that even little numbers can grow quickly into larger ones, to the point of becoming unpleasant surprises.

• Accordingly, managers must be alert to these expenditures and must develop methods of monitoring and control. For example, most communication systems today have electronic entry codes. They ensure that only authorized staff incur expenses. If employees exceed their authority or abuse their access, remedial action can be taken. The use of such codes has an immediate and dramatic effect on telephone, fax, and photocopy excesses. Abuse of costly overnight delivery services as a defense against almostmissed deadlines is not as easy to control and requires real management diligence.

MONITORING FINANCIAL PROGRESS

Management can monitor financial performance in a number of ways. The most obvious is to compare actual results for a month, quarter, or year with the budget and the comparable period for the prior year. A good financial statement, balance sheet, or income statement will give a manager all that information on one piece of paper.

Another important monitoring technique is the comparison of the station’s or system’s financial progress with that of peers. As noted earlier, one of the principal sources that provided comparisons for radio stations has been discontinued. However, television stations still can benefit from an examination of the NAB/BCFM Television Financial Report.

There are other sources for comparative information. One consists of newsletters and annual reports issued by Paul Kagan Associates, Inc., of Carmel, California.9 Annual reports include the Radio Financial Databook, TV Station Deals & Finance Databook, and the Broadband Cable Financial Databook. Additional sources are available from the Radio Advertising Bureau (RAB),10 the Television Bureau of Advertising (TVB),11 and the Cabletelevision Advertising Bureau (CAB).12 Revenue reports for some markets are compiled by Miller, Kaplan, Arase & Company.13

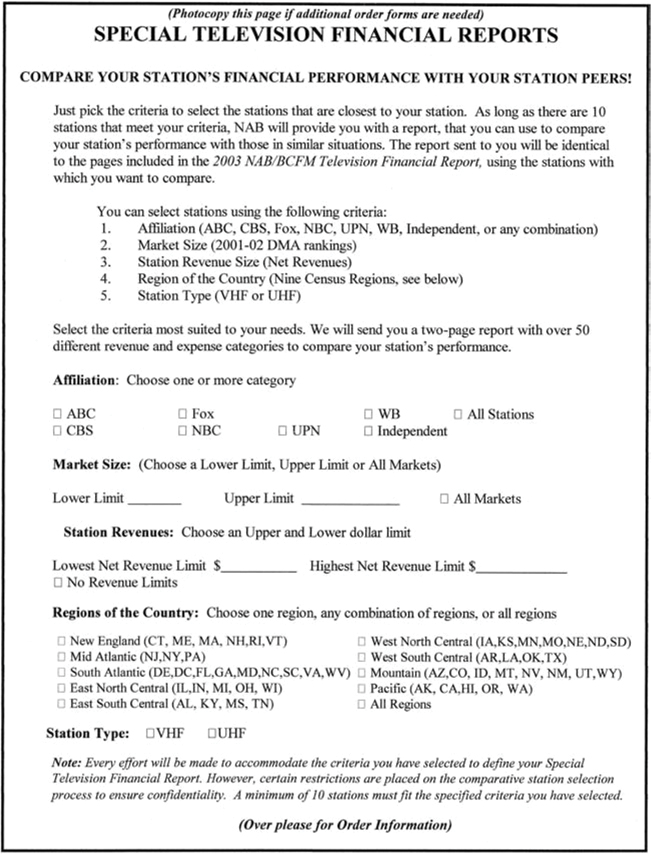

Another useful tool is the NAB’s Television Financial Monitoring System, whose customized reports allow for the comparison of financial results of a particular station with those of similar stations. To use the system, it is necessary to send the NAB a special order form with details of the stations for which comparative data are desired (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 NAB Special Television Financial Reports order form.

(Reprinted with permission of the National Association of Broadcasters.)

Additionally, in some markets, stations report their revenue results to an accounting firm retained by all stations. Where available, this procedure provides a method of determining a station’s revenue performance as a percentage of the total for the market. Since stations are no longer required to report their financial results to the FCC, this can be a valuable method of monitoring station and market performance.

Financial results are now the most important measurement of a manager’s effectiveness. The electronic media manager must be knowledgeable about these important matters.

WHAT’S AHEAD?

No one can predict the future in a consolidating, technology-driven industry like electronic media with any accuracy. All we can do is spot trends.

One emerging trend is publicly traded megacompanies that are vertically and horizontally integrated. Public companies are earnings-driven, and the market is unforgiving when profit forecasts are not fulfilled. As consolidation progresses, more and more publicly-traded entities will be operating radio and television stations, even in small, unrated markets.

The stock market has begun to question the underperformance and economics of these megacompanies.14 As shareholders watch the declining value of their equities, it does not take too much imagination to understand how important financial performance skills will be.

More than ever, financial management will be the measure of management success. Accordingly, it is vital that any aspiring broadcaster, cablecaster, or future electronic mediacaster of whatever technical innovation comes along be well acquainted with financial terminology and concepts.

Electronic media students should include computer, business, accounting, and financial courses in their curriculum planning. The industry will become more centralized as to product and management. It will be more computer-driven, and the number of program staff will decline. What will be left largely will be financial, sales, and promotion personnel.

SUMMARY

Financial management demands an understanding of the accounting function, basic financial statements utilized by managers, methods of preparation, and the terminology employed.

The accounting function begins with the budget process, continues with the recording and reporting of transactions, and concludes with an analysis of financial results.

The budget is a planning and control document that plots the course of projected financial transactions (i.e., revenue, expense, profit, or loss). Actual daily results are recorded in journals and ledgers, and are transferred to financial statements by using charts of accounts. The two main financial reporting forms are the balance sheet and the income statement. The balance sheet reveals the condition of the business at a fixed point in time. It discloses total assets, liabilities, and capital of the operation. Ratios are then applied to balance sheet results to determine the relative strength or weakness of the company.

The income statement is another measure of financial health. It measures revenue and expenses, resulting in profit or loss for a given period of time.

After the results are reviewed and compared with the budget, cost control methods may be required. Even if financial results meet or exceed the budget, the electronic media manager might still be underperforming. Financial progress also is judged by a comparison of the results achieved with similar facilities inside or outside the market. Once made, those additional comparisons may require management to effect further changes in station or system operations.

CASE STUDY

Dustin Hoffman is busy burning his graduation shoe leather making the rounds of well-situated communications graduates from his alma mater, “I Can’t Believe U.”

Dustin’s interviews have focused his attention on what he should have learned but did not. Collegiate Bowling 101 was a sure GPA builder but it was not accounting concepts. Mating habits of the North American Bison was no substitute for Software Concepts for Managing Information in a business that sells intangible products.

It seems that his best opportunity is with an ailing radio station blessed with a new owner, an alumnus, who pawns the station through intensive sales, electronic efficiency, and multiple-hat staff members.

Dustin’s offer from WFIX-FM is an entry-level sales position. He must oversee the installation of a computerized accounting and monitoring system to track sales performance and profits.

It’s either this or go to work in his father’s waste management business. He takes the job, and has to solve the following problems.

EXERCISES

1. Where can he get some basic information on accounting terminology and methods for a stand-alone radio station?

2. Where can he find a specialized software company that can provide an “off-the-rack” user-friendly accounting system?

3. What basic accounting statements will Dustin want the software to produce? Why?

4. What tools are available to monitor his station’s performance against its peers?

NOTES

1 Radio Business Report, Morning E-Paper, July 16, 2004. http://www.rbr.com/epaper.

2 “1994 Career Guide,” U.S. News and World Report, November 1, 1993, pp. 78–112.

3 Ken Kerschbaumer, “Data Is Power,” Broadcasting & Cable, June 7, 2004, pp. 48–49.

4 Ibid.

5 Accounting Manual for Radio Stations. Washington, DC: National Association of Broadcasters, 1981.

6 Broadcast Accounting Guidelines. Northfield, IL: Broadcast Cable Financial Management Association, 1996.

7 NAB/BCFM 2004 Television Financial Report, p. 36.

8 NAB/BCFM 2004 Television Financial Report, p. 37.

13 http://www.millerkaplan.com.

14 Radio Business Report, Morning E-Paper, July 16, 2004. http://www.rbr.com/epaper.

ADDITIONAL READINGS

Jablonsky, Stephen F., and Noah P. Barsky. The Manager’s Guide to Financial Statement Analysis, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2001.

Radio & Television Business Report. Lake Ridge, VA: Radio & Television Business Report (published monthly).

TFM: The Financial Manager. Northfield, IL: Broadcast Cable Financial Management Association (published bimonthly).

Tracy, John A. How to Read a Financial Report: Wringing Vital Signs Out of the Numbers, 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

Understanding Broadcast & Cable Finance: A Handbook for the Non-Financial Manager. Northfield, IL: BCFM Press, 1994.