5

All Broadway shows start with the prep period. This begins weeks if not months before the show and consists of the planning of the system and creating the drawings and paperwork for the system. It includes production meetings and site surveys of the theatre. It is entirely possible that the mixer has not been hired in the beginning stages of the prep period. The prep period leads to the shop build, which is when the sound system will be pulled from a sound rental shop and labeled, built, and tested in the shop. The prep concludes when the system is loaded onto a truck at the shop and sent to the theatre for the take-in or the load-in.

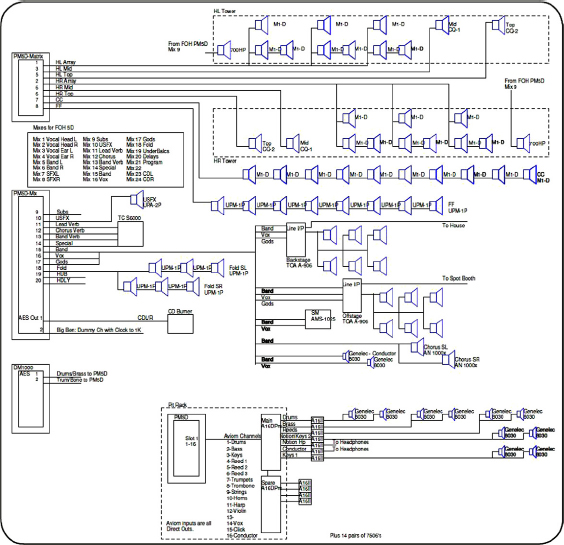

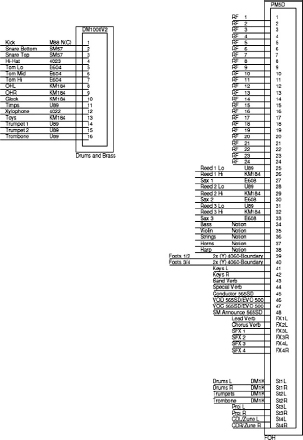

The job of the design team is to design the system and gather the information from other departments about their needs. Once the designer has the information he needs he draws out the sound system. This could sometimes be as simple as a hand drawing on a piece of paper to a more elaborate Vectorworks or Stardraw drawing. The designer’s job is to give a detailed overview of the system so his team can flesh out the system with rack drawings and cable schemes. The following drawings are examples of what the designer will normally pass on to his team. It is important to note that USITT, the United States Institute for Theatre Technology, Inc., is working on standardizing sound drawings and terminology, but this has not happened yet and has definitely not made any headway on Broadway. These are drawings that you might receive from a Broadway designer, but they may vary from what USITT calls standard. I look forward to their standardization, but I think it will take years before we see it really take hold.

Figure 5.1. A typical signal flow output drawing from a sound designer. USITT calls signal flow drawings block diagrams.

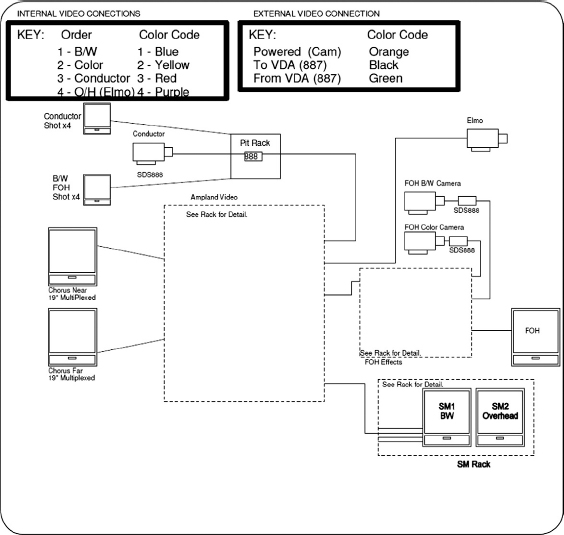

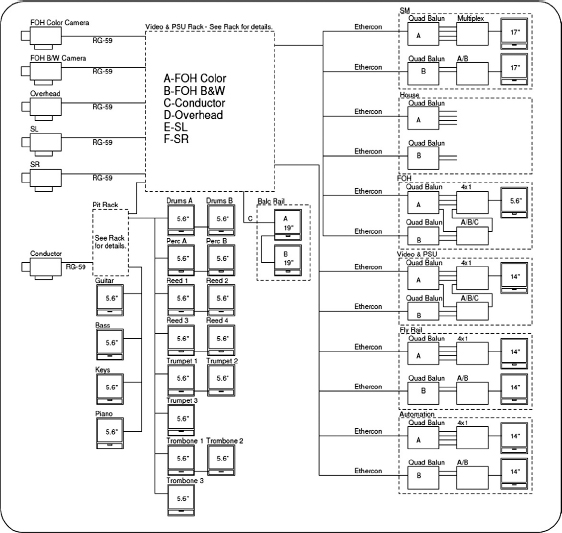

As you can see, the point is to give a decent overview of the sound system. The drawings are simple but contain most of the information needed to flesh out the sound system. From these drawings, typically, the associate or the assistant will go a step further and start doing drawings that further explain the sound system. The next step would be to layout some other basic information about the system. The most important aspect of any sound system outside of the inputs and outputs would be the intercom, video communication, and paging parts of the system. Inputs and outputs are relatively straightforward and easy to understand, but these other parts of the system can be very complex and each designer has his or her own special method of doing these systems. It is up to the assistant or associate to lay these systems out in a way the designer likes, allowing for any special needs of the other design teams. Lighting has the most important requests when it comes to intercom. Some lighting designers like their com a very specific way and their assistant is usually a good source to ask about the needs of the lighting department. Once this information has been pulled together, the associate or assistant will add more signal flow drawings.

Figure 5.2. A typical signal flow input drawing from a sound designer.

The most important thing to note about these drawings is that they are overviews and not overly detailed. A mistake some people make is trying to overload information on drawings. Keeping drawings simple and to the point can be more effective. The idea of these signal flow drawings is that designer. someone can pick up a drawing and quickly understand the components of the system. The idea is not to convey every detail about the components. These drawings rarely detail anything about cabling or specific focus or rigging. That information is saved for other places. Other drawings that can be helpful at this stage are signal flow drawings for the computers, Midi routing, and the paging system. It is possible that the design team will include more drawings, but that is a matter of preference with the designer. These basic drawings are the foundation needed for a system to be built. Everything else can be fleshed out by the production sound or the mixer.

Figure 5.3. A typical signal flow intercom drawing from a sound designer.

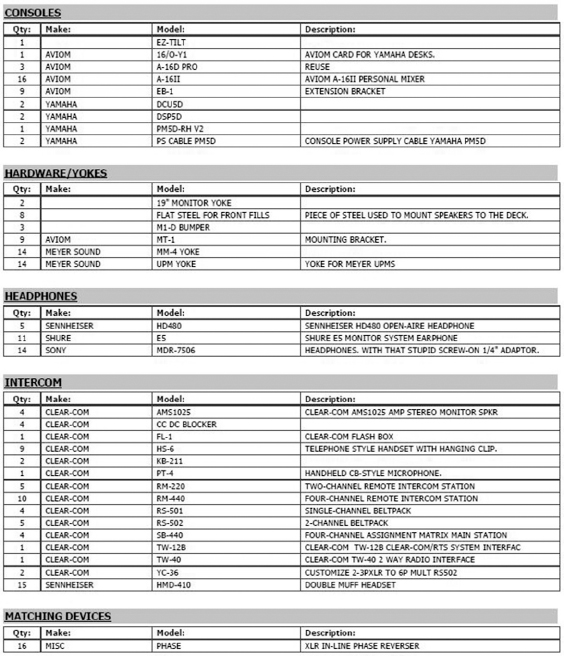

The other important task the design team has is to create an equipment order and bid it out to the sound shops. All Broadway shows bring their own system into the theatre. On very rare occasions the producers will buy the sound system. Hairspray and The Producers and The Lion King are shows that own their sound system, but this is definitely not the norm. More often the equipment is rented from a sound shop. Currently the major sound shops in New York for Broadway are PRG, Sound Associates, and Masque. The designer is responsible for creating an equipment order that can be bid on by these shops. The shop with the lowest bid will get the show as expected. The list of equipment the designer puts together is not a complete list of every item needed for the system, but rather a list of the big-ticket items. It includes all of the equipment in the signal flow drawings.

Figure 5.4. A typical signal flow video drawing from a sound designer.

The list may or may not include the cable and mults for the system. Shops are very used to this and they bid based on the major components of the system. They are used to estimating the cable and other parts and pieces needed to finish off the system, but as the shop time gets closer the shop will want the list fleshed out to include every detail about the sound system. It is very important to get the big-ticket items on the list from the beginning. A common saying is that it is easier to cut than add. Typically what happens in the bidding process is that the shops go as low as they can to win the show. Once they get the bid they are not expecting major changes to the order. If you forgot to put a couple of Meyer CQ-1s on the order and you add them after the bid has been awarded, then don’t be surprised when you get a call from the production manager asking why the shop is calling and trying to raise the rental cost based on changes to the system.

Accuracy counts and it costs. You won’t make any friends if you get to the shop and double the budget. At the same time, if it was on your list and the shop agreed to it, then they are required to supply you with that gear. I am currently building a show and the designer included a specialty speaker with a note that said “with proprietary cable” as a note about the speakers. Once we were in the shop, the shop did not want to supply the cable. Instead they wanted to make it a perishable, which meant that the production would have to pay $300 for a spool of cable. The designer simply called the shop and pointed out that it was noted on the order and they agreed to his list. The shop acquiesced and gave us the cable as part of the rental.

I designed a tour of A Chorus Line and the production manager asked me to put a Genie lift on my order because he was having trouble getting it from the lighting shop. Sound shops typically do not have Genies, but I put it on my order. After a shop won the bid they realized that there was a Genie on the order that they had overlooked. They weren’t happy about having to supply it, but they did, and acknowledged that it was their mistake for not noticing it. In the end it was worked out so that no one was upset, which is the objective. It is rarely worth a fight.

You have to be careful with arguing about your list and what you are entitled to. If you are going to insist that the shop supply you with something on your list and you throw a fit that they agreed to it and they have to supply it, then be prepared to have a hard time getting the amp you forgot to add to the list or the speaker the director asked for after the bid was awarded. If you are going to put up a fight for something, you better make sure you haven’t missed anything. Sometimes you have to barter and trade. Keep in mind that the shop is trying to make money as well as make you happy. It is a hard balance. On one project I was getting close to the end of the build and had a stack of cable and gear worth about $20,000 that I didn’t need, and I found out I was short a $100 SM58. I asked the shop for the mic as an add, and I was told the budget was so tight that they couldn’t supply me the mic. I responded by stating that I had intended to give them back all of this gear that was on my order that was no longer needed, but since I couldn’t have the mic, I would keep it instead. The shop gave in and I got the microphone.

Figure 5.5 shows a page from a typical equipment order. This is a detailed list of the gear needed and the quantity. The shop is not the enemy when it comes to the list. The shops are good at looking these lists and making guesses about what else might be needed for the system and what it will cost. If the shop does their job, they have anticipated the thing you might have forgotten from your list and they will not be surprised unless your adds become out of control and expensive. Just keep in mind that it is a business and the shop has to make money. The worst equipment order I have ever seen listed only the big-ticket items like amps and speakers, and then had a note that said, “And everything else to make a functioning sound system.” Not the best way to do an equipment order, as it leaves you without a leg to stand on when you try to point out the necessity of some expensive piece of equipment and the shop says they don’t agree that it is required to build a functioning sound system.

In the end, though, the shop will try hard to please the designer. Designers develop loyalty to shops and when the designer feels taken care of he will want to go back to that shop. The bigger the designer, the more the shop will try to please the designer because they know the designer will push for their shop on the next show. There are times when the shop is less concerned about the profit on a single show and more concerned with the impression they make on the designer and the production manager or technical director. If this is the case, the shop will give you just about anything you want because they are looking at a bigger picture. This always makes for a pleasant build. If this stage is dealt with properly, the design team will establish a good relationship with the shop and provide them with an accurate list that allows the mixer to build the show without too many conflicts.

Figure 5.5. A typical equipment order from a sound designer.