THE SHOP

Once all of this has been worked out, the next step is for the mixer to go to the shop and build the show. This is where the system starts to become the mixer’s and this is where a mixer starts to prove his worth. In the shop we label and rack all the equipment and cable. We also plug the entire system together and test it. Most mixers are very particular about how racks are built and what they look like. Mixers can also be very picky about how racks are labeled and patched and how the spare cables are tied up. Good mixers pride themselves on their finished systems. The look of the system is a representation of the mixer, and the cleaner and more thought out it is, the better a mixer looks. Nothing is worse than having another Broadway mixer stop by and look at your system and have it look a mess. It pays to take pride in the way your system looks. As a mixer you are showing people your skills and your work ethic when they see your system. If your mix position is a mess, then they will think your mix will be a mess as well and people will be less likely to want to work with you.

To be successful in the shop you have to understand the world of the shop. Just like you must understand the hierarchy of the design team, you must also understand the hierarchy of the shop. You have to understand who you can talk to and how to ask for something. You have to understand the timing of the shop and when to get concerned. You have to understand the order at which gear is going to come to you and how to deal with it in that order. You have to understand how to orchestrate the build. We will go into great detail about what the crew actually does in the shop in Chapter 9.

Most designers have no interest in the shop or the process of building the show. It is not that they do not care; it is not their job. A majority of Broadway musical designers were at one time mixers and they are probably more than capable of prepping a system in the shop, but when they are in the designer role their place is not in the shop. That is not to say that the designer is not important to the shop build. In fact, because the designer is removed from the build he can actually be a very strong asset. Most issues that arise in the shop can be dealt with by the mixer but some require the clout of a designer to accomplish. When those issues arise, it is time to call the designer. The designer can be a major asset in the shop because he can be the heavy. The designer can be the one who calls and pitches a fit so you don’t have to. The result is that you get what you need and no one has an issue with you. If you throw the fit, then the shop could turn on you and you could find it hard to get anything done.

Just as with any field, there is a hierarchy in the shop. It is important to understand the key positions and how they relate to the build. It is important to know who to talk to when you have a problem. It is also important to know who to talk to when you need some equipment. Shops have a very structured system of building shows. If you don’t understand the shop’s system you are bound to get in trouble. You need to understand what a build zone is and what the foreman does and what the salesperson is responsible for. It could take a dozen builds to fully grasp how shops work. In this section we break it down.

The first person you are likely to talk to at a sound shop is a salesperson. What’s odd is that person is called a salesperson, but doesn’t really sell anything. The title is a little misleading because the salesperson is in charge of making sure all the equipment needed for a show is available. This is the person who will take the designer’s equipment list and put it into the shop’s computer system and book equipment for your show. A good salesperson is an incredibly important part of having a successful build. A bad salesperson can leave a build in shambles.

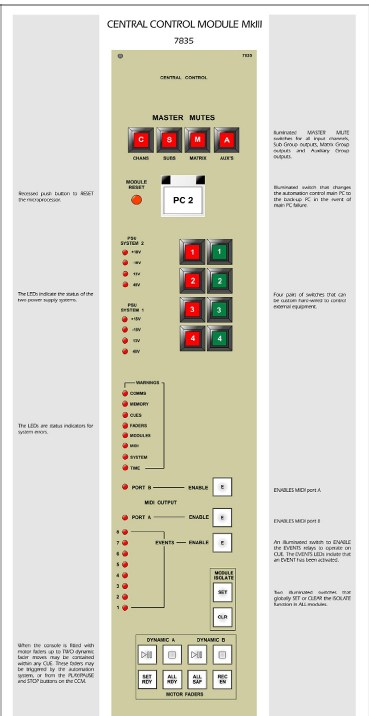

The salesperson is in charge of getting approval to order equipment for the show and ordering the equipment. If the salesperson does not order equipment on time, the show could be in real jeopardy. On one show I did we were using a Cadac, which is still the best-sounding and best-feeling console you can mix on. A Cadac is an analog console with some automation built in. To make the automation function, you need a computer running a program called Séance and a piece of equipment called a CCM. The CCM is the Central Control Module for the console. Without the CCM the console will not connect to the computer and there is no automation. You are left with an analog desk. The salesperson for the show forgot to order a CCM and by the time I found out, the delivery time for a CCM was scheduled for our first preview. It was a disaster of a situation and led to many phone calls. Luckily a solution was found, but it shows how the neglect of a salesperson almost took down a first national tour.

Every sound shop has some form of database software that tracks their equipment. This software keeps track of every piece of gear owned by the shop and when it is booked and when it is available. In the case of the larger shops that have offices all over the country, this software also has to keep track of equipment in other parts of the country. The salesperson is responsible for booking equipment for your show. The salesperson takes the designer’s list and any other supplemental lists and inputs it into the shop’s system. As the salesperson does this he or she can see how many items will be available for your show. The person books the equipment so it will be locked out for any other show.

This is an easy process if the shop has all of the equipment on your list in stock. It becomes increasingly more difficult as they find gear that is not available. They then have to look to see if it is in another shop and if it is more cost effective to ship it or purchase a new one. Then they start looking at your show dates. It is possible they will have the equipment but not until you leave the shop. When this happens, they will ask you if they can drop ship the equipment to you and most of the time this is acceptable. The next step is for them to buy the equipment needed. This requires approval by people above them, which usually requires the salesperson to put together a list of all purchases to analyze whether the show is costing too much. At this point it is common to get a call asking about substitution and most of this is done in the bidding process.

Figure 7.1. A Cadac CCM.

Once the equipment order has been fully booked in the shop’s system, it is up to the salesperson to keep tabs on the status of equipment deliveries for the show. That person is also expected to look out for missing holes in the equipment order. It is not uncommon for a salesperson to point out pieces of equipment you forgot to put on your list. A salesperson is not required to be a mixer or a stagehand. A salesperson may have never built a show or mixed before. None of that is part of his or her required skill set. The salesperson’s job is to know gear. Salespeople know more model numbers than any human should. They could literally hold a conversation for minutes using only numbers and letters. They may have never used an Aphex 1788a and they may have no clue how to use it, but they know that there is a version with a LAN connection and a version with an RS422 connection. They also know that you have to use a specific router with the units.

Good salespeople are an incredibly valuable resource and should be treated with respect. It is a hard lesson to learn, but the salespeople are on your side. Really the only things not on your side are money and time. Given an abundance of those two things you can have anything you want for your sound system, but when those are in short supply then decisions have to be made about how to get the show up and running. Sometimes those decisions are tough, but it is important to know that the salespeople are just messengers. They cannot allow or deny a piece of gear for you. They can merely book it or purchase it for you.

At a certain point the salesperson will start talking to the mixer to find out about the supplemental equipment needed for the system. It is at this point that the mixer takes over the list and must maintain a good record of what is needed and when it is needed, and must communicate changes that arise as well as mixing items from the list as soon as possible. The first task to be done in the shop is to have the shop print out a list of what is on your order and to cross-reference the shop list with the designer’s list. It is important to know from the start of a build that the shop is fully aware of every item needed. The shop runs like a machine and people all over the shop are pulling equipment to fill your order. If the list is accurate, then you can count on getting most if not all of the items on your list. As the shop pulls the gear, they mark it in their system so they can constantly see how many items you ordered and what you have been given and what you are still owed. If the two lists are accurate, this process goes smoothly. If you do not take the time to check the shop list, you could find out halfway through your build that a clerical error was made and only half the speakers are on the shop list, which could put you in a bad place if they do not have the speakers in stock. Making sure these lists match is a tedious process, but it is crucial to a successful build.

Once the rental list has been hashed out, the salesperson will want to go over the perishables list, which is a list of equipment the show will need to purchase. This list can include all wireless mic supplies such as batteries and canned air. It can also include items that were on the designer’s rental list but the shop considers those items perishable. The perishables list can also include items such as P-Touch tape and electric tape. There are times when it is more cost effective to buy the perishables somewhere other than the shop. The shop usually does not care if you buy the perishables somewhere else and the money you save can get you some brownie points with the production manager.

Most of the sound shops around New York City are union sound shops and they have a similar structure. The sales department is the non-union front office part of the shop, while the show build area is the union part of the shop. This area usually looks like a giant warehouse and the person in charge is the foreman. The shop foreman is a key player in how well the shop runs. The shop foreman meets with the sales department and goes through the paperwork supplied by the design team. It is always a good idea to pass on drawings of the sound system to the shop as early as possible so the shop can understand the scope of the show.

The shop foreman looks over the scope of the show and lays out a plan for the build. Most shops have specific show prep areas and the shop foreman books shows in the build areas, or zones. The shop foreman also assigns a key to the show and communicates his concerns to the sales department so that those concerns can be discussed with the design team. The shop foreman also watches out for the overall safety of the people in the shop as well as the people who have come in to build and the equipment. It is not uncommon for the shop to tell you that you have to change the way a rack is being done because it will be better for the gear another way, and since the gear is a rental and belongs to the shop, you should listen to their requests. If you don’t and the gear comes back to the shop broken, your show is going to have to pay for the equipment. The shop foreman also makes sure trucking has been arranged.

A well-run shop is the work of a good foreman and a pleasure to work in. When the foreman is less than stellar, it can really hamper a show. Gear might not show up to the zone on time because the foreman didn’t book the right labor to pull your show, or the gear could be lost because the foreman hasn’t had the shop people cleaning the shop enough once shows return. When you are in a shop and you are digging through racks of untested gear that just came back from another show just to get your system built, then you know there is a problem with the foreman. Odds are the next time you come back to the shop it will not be like that, because no shop can survive for long in a state like that. Luckily the shops employ some top-notch foremen who are knowledgeable and helpful.

When you arrive at a shop to build a show you will be introduced to your show key, who will take you to your build zone. The show key, sometimes called the show captain, is the most important person in the building to your build. The show key’s job is to bring you equipment. The shops do not want you wandering through the shop picking up gear on your own. They want to bring it to you so they have a count of what you have been given. The show key takes the shop equipment order and pulls it and brings it to your zone. The show key usually starts pulling your show several days before you arrive so you will have gear in your zone waiting for you. No one likes walking into an empty zone.

The show key is your conduit to communicating with everyone. If you need to talk to the foreman you tell the key and he will bring the foreman over. The show key does not have the authority to add equipment to your order, so if you need to add something the show key will bring the salesperson over. If you need to know when the console will come into the zone, the key will check with the console department to find out. All shops are divided up into different departments. There is an amps and speakers department, a video department, a microphone department, and several other departments. There are people in these departments who are all looking at your order and pulling, prepping, and testing equipment for your show. It is the key’s job to communicate with those departments and make sure everything is on track. A good key can head off problems without you even knowing about them. He can look over the drawings and paperwork for the show and anticipate problem areas. A good key can also point out things that may have been overlooked, forgotten, or planned incorrectly.

For this machine to work the way it should requires diligent planning and paperwork for the design team. An accurate equipment list is crucial. Without an accurate list of what the show needs the build will be hamstrung. Time is also crucial. The most successful builds happen when an accurate list and accurate show drawings are supplied to the shop weeks if not months before the prep begins. This gives the shop time to communicate with the designer and come up with adequate substitutions, and then time for the salesperson to enter and book all of the equipment. And then time for the foreman to develop a plan for the build. And then time for the show key to look over the paperwork and start pulling the equipment. When done right, the mixer can even suggest what he would like to see in the zone on day one.

One thing that can mess this system up is the bidding process. There are times when the bidding process drags on and runs right up to the day of the build. There have been shows that didn’t know what shop they were going to until the day before the build. When this happens, everyone is bound to be frustrated and unhappy with the build. If you walk into a build zone with nothing in it, you should take the time to understand why. Was it that sufficient time was not given to the shop to allow them to prepare for the build? If so, then you have to find a way to be patient. Was it that adequate paperwork was not given to the shop so the shop is not fully aware of the equipment needed for the show or the scope of the show? If so, then you have to help get the shop the information they need and you have to understand that it is not the shop’s fault. Was it that the shop underbid the other shops to get the show, but they are too busy to deal with the show and they just built a dozen shows and they have no gear? If so, then it is going to be an ugly build with the shop being defensive and everyone else being angry.

No matter what the reason or the state of the shop, the mixer’s job is to build a sound system. An angry mixer does not accomplish much. A mixer has to make the best of whatever situation he or she has been dealt. You can complain all you want about the shop but the fact is you were hired to make it work. The designer does not want to hear excuses. The audience and the director are not going to hear that you had a bad time at the shop. Your job is to do your job and make it look easy. That will get you hired again.

There are five lessons I have learned about dealing with sound shops. I have spent a great deal of time in sound shops in every position possible. I have been a designer and an assistant. I have been a mixer and a production sound. I have also been label monkey number three and box pusher. Working in rental shops is an integral part of doing sound and it takes some getting used to. The different positions require different tools and sensibilities. Dealing with shops is a skill that is learned through mistakes, and every mistake takes time to be forgotten. Without the shop you have no gear. Without the shop’s support you have no help. Without the shop on your side it is a steep hill to climb, but once you get comfortable working with the shop things get much easier. So after many personal mistakes, here are the five lessons I have learned about sound rental shops.

Your Lack of Preparation

This is a classic stagehand adage. Your lack of preparation does not make this my crisis. Sometimes expressed as “Not my problem” and at one theatre where I worked it was just simply “NMP,” which was printed in giant block letters near the pin rail. And it is as true as can be. When I was just getting started, I ended up in the shop on several occasions with three days to do fifteen days of work and having been hired the day before. I made the mistake of going to the shop in crisis mode. I would be wound tight and agitated at everything. “Why don’t I have this? Why isn’t that done already?” It took me time to understand that the people working in the shop work there every day, and this problem was mine and not theirs.

The Shop Is Not the Enemy

My first experiences in the shop were as just show labor. I worked under other people building shows and I learned some great lessons from them. I learned how to build a show and where to put labels. Unfortunately, I also learned one lesson that was not so good and took me quite a while to unlearn. That lesson was the shop is the enemy. The truth is the shop is not the enemy and you want them on your side. It is easy to get into arguments with the shop and become unreasonable and demanding. Man, I made that mistake too many times and it gains you nothing. It is such a cautious balance trying to get your show built on-time and under-budget with so much out of your control. Just remember, you will get the Cadac and the RF rack just in time to push it on the truck, but you will get it.

Learn Your Terminology

Steck Rails. G-Blocks. Mults. Bundles. Waber strips. Show Key. And much, much more. There is so much terminology involved with building a show and it takes time to learn. Different shops have different terms and different parts of the country have different conventions. In New York shops, a bundle is a group of cables taped together. In other places it is called a loom. Power strips are called Waber strips because that was the manufacturer at one time and the name stuck. Same thing with a Sammy, which is a big wooden box affectionately named after the maker at some shops. This minutia is important to know. It makes working with the shop so much easier if you can talk to them in their language.

Build a Relationship

When I got my first big design job I thought I was the stuff. I thought, “Look at me. All the shops are going to be clamoring to get my show.” Woof, was I wrong. I put together my equipment list and sent it out to all the shops and then waited by the phone like a schoolgirl after a first date. And then nothing. No one called. So after a few days, I called them and found out that no one was interested in my little show. I then started panicking. I had a tour to design and I needed equipment and I had nothing. Finally I found a shop that was willing to do the show, and that is when I realized how important it is to build a relationship with the shops. Part of the reason is that until you have established yourself with the shop, they have no idea how legit the show is. They don’t want to waste their time if the gig isn’t going to happen. Also, even though I thought I had a big fat show, looking back now I realize that the budget was horribly low, so it was no wonder no one wanted it. Now that I have done lots of work with the shops, it is easier. It is also getting logistically easier. The more I work with a shop, the more they know what I want and my shortcomings, which makes for a simpler process. At this point I prefer going to a shop I have worked with because it is much easier than starting from scratch.

Have Fun

I have found that the more light-hearted I am, the better things turn out. If I roll with the punches I seem to get punched less. If I am open and will allow substitutions, then things are smoother and I usually get the system built faster. If I can accept that other people might have a better idea than I, then I usually end up with a better product. I have good friends at the shops and look forward to going and building shows. I know there are some people who remember some of my youthful mistakes and haven’t forgiven me for them, and I don’t blame them, but you don’t make omelets without… well, you know. I am still learning the rules and trying to get better at the process of building shows and working with the shops. Maybe one day I will perfect it, but until then I will try to laugh at my mistakes. After all, it is only theatre.